Sonobeat Records | The Beginning of the Austin Music Scene | Interview with Bill Josey Jr. aka Rim Kelley

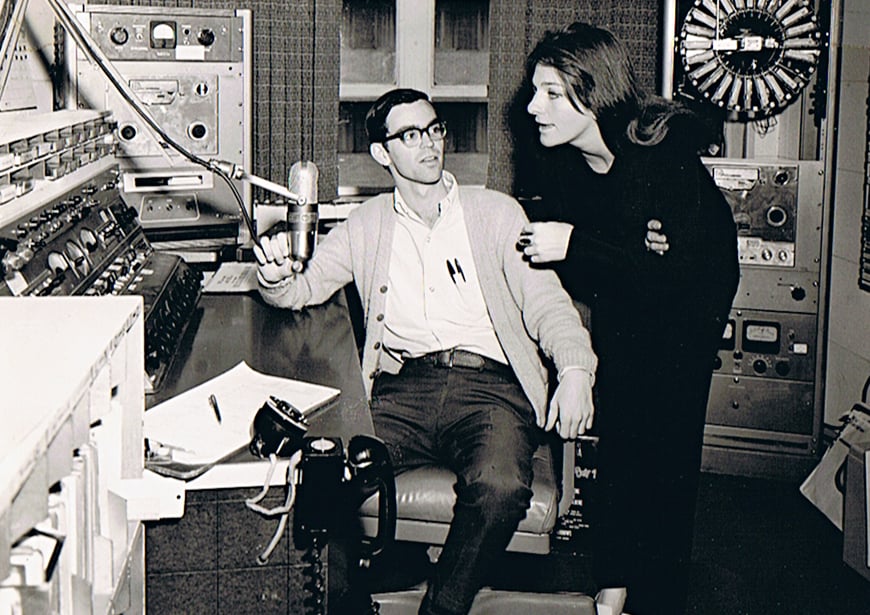

Sonobeat Recording Company is founded in Austin, Texas, by Bill Josey Sr. and Bill Josey Jr. at the beginning of 1967, but its roots date from October ’64, when Bill Jr. begins working as a deejay at KAZZ-FM in Austin.

The formation of Sonobeat is a natural extension of KAZZ’s live remote broadcasts, if not of KAZZ itself. Bill Josey Sr. is KAZZ’s general manager. Bill Jr. (who goes by the on-air pseudonym Rim Kelley, a name he’ll continue to use as a Sonobeat co-founder and record producer) is KAZZ’s afternoon and weekend deejay and, in 1967, its program director.

But even giving due credit to KAZZ’s influence, Sonobeat really begins as a dream separate and distinct from the KAZZ live remote broadcasts: one of Bill Jr.’s high school classmates composes religious music – hymns and chorales – and is frustrated by his inability to attract established music companies to publish his works. Desiring to help his friend promote his music, Bill Jr. forms a music publishing company in 1964 that later morphs into Sonobeat’s publishing affiliate, Sonosong Music Company. Conceptually, Bill Jr. envisions that his publishing company will record and distribute albums of Austin church choirs performing his friend’s works, and the recordings will be used to publicize their availability. Although Bill Jr.’s music publishing venture never does record or actually publish any of his friend’s compositions, it seeds in both Bill Jr. and his father, Bill Sr., the idea for a combined recording studio, record label, and music publishing company that will serve the rapidly expanding Central Texas music scene.

“Austin in the mid ‘60s was a mixed bag of musical styles”

When did you first get interested in music?

Bill Josey: I was pretty young. I had a kid-sized portable 78 RPM record player in my room – and a selection of Little Golden Records ranging from nursery rhymes to dramatizations of children’s stories with character voices, sound effects, and music – when I was pre-school age. In elementary school, I got hooked on Broadway musical, movie soundtrack, classical, and jazz albums that I listened to on my parents’ console record player. By fourth or fifth grade, rock ‘n’ roll had become pervasive on our local radio stations, and that hooked me, too. Some of the first “hits” I remember singing along with were ‘Rock Around The Clock’, ‘Purple People Eater’, ‘Ballad of Davy Crockett’, ‘Hound Dog’, and ‘Mr. Sandman’.

How do you feel about the fact that Sonobeat has been active since the sixties? When did the company officially register?

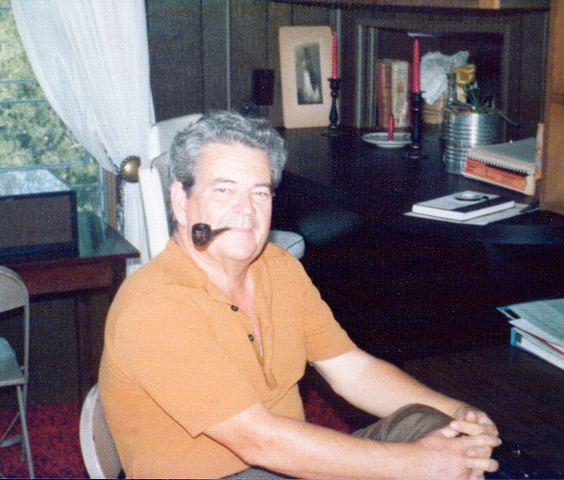

My dad and I officially launched Sonobeat (rhymes with oh-no-beet) in May 1967 in Austin, Texas. At the time, I was an undergrad at The University of Texas in Austin. I left to attend law school in Houston in September 1970, and Dad continued the business solo until he passed away in September 1976, so Sonobeat’s active life span was nine years. With Dad’s passing, Sonobeat fell dormant, and we packed the Sonobeat master tapes and other archival materials away. It wasn’t until the turn of the millennium that we began cataloging the archives. By 2004, my brother Jack, who’s been the steward of Sonobeat’s archives for 45 years, had fully cataloged the library and digitized most of the tapes, which is when we decided to launch the Sonobeat website to celebrate the dozens of acts and hundreds of musicians Sonobeat recorded during its active years. And it wasn’t until 2014 that we finally broke open the catalog for digital reissues. To be clear, there have been no new Sonobeat recordings since mid-1976. Our current activities, under the auspices of Sonobeat Historical Archives, are to continue to build out the SonobeatRecords.com website, fleshing out the stories of the artists Sonobeat recorded, and to restore, remaster, in some cases remix, and reissue material from the catalog.

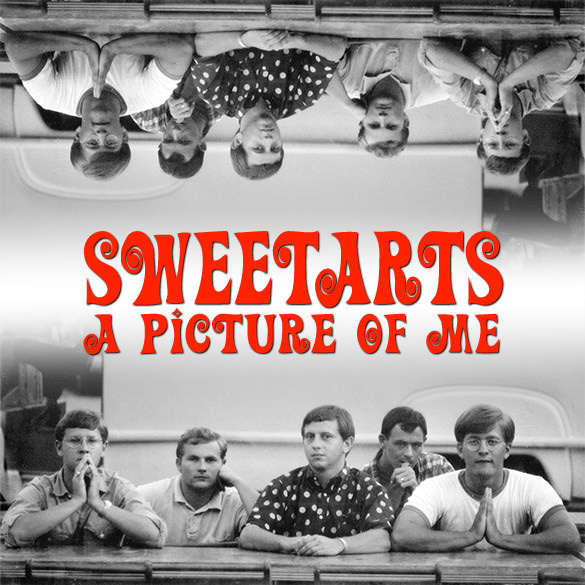

Our first reissue, in 2014, was the Sweetarts’ single – which also was Sonobeat’s first vinyl release, in 1967 – ‘A Picture Of Me’ backed with ‘Without You’.

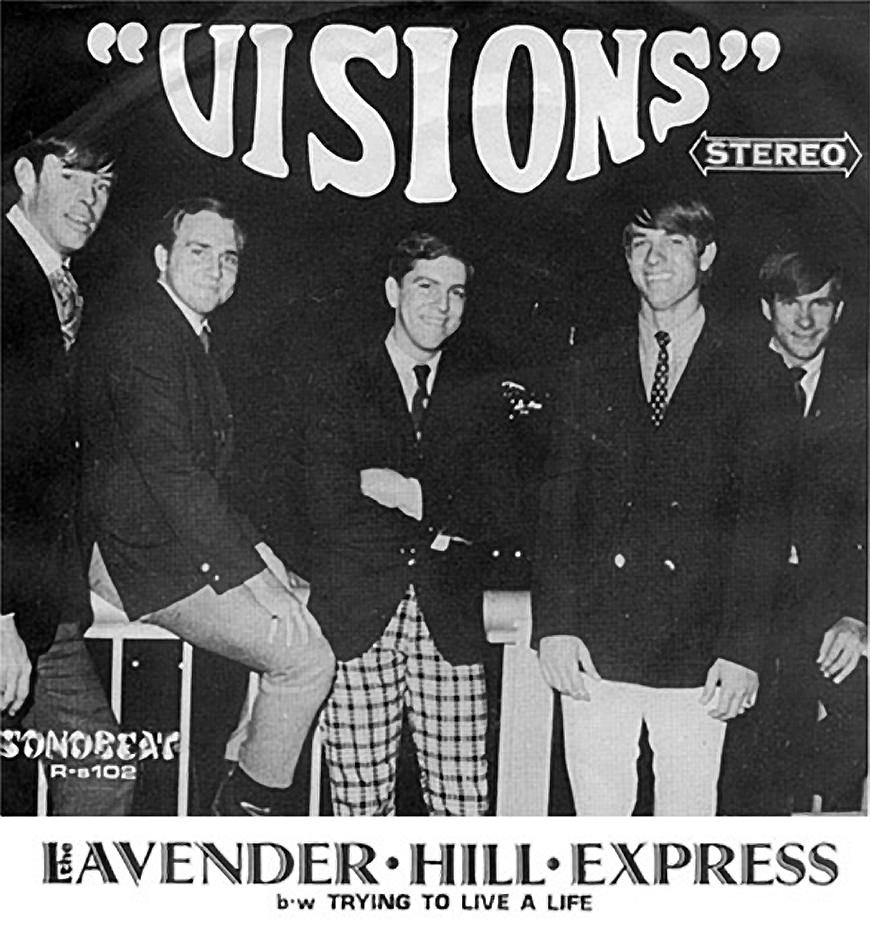

Occasionally we’ve issued digital versions of previously unreleased material from the archives, such as Lavender Hill Express’ ‘Trouble’, a song written by Texas outlaw country legend Rusty Wier, which we included as a bonus track in our 2014 ‘Visions’ digital EP reissue that features the band’s three Sonobeat singles from the late ‘60s. In 2018, we authorized use of an unreleased track by Tom Van Zandt (a founding member of the Sweetarts) along with half a dozen other previously-released Sonobeat tracks for the soundtrack of the sci-fi mini-series Orbital Redux that ran on the Nerdist online video channel Alpha.

You were involved with radio station KAZZ which is credited as the first FM station in the U.S. to regularly program rock ‘n’ roll music.

I had interned at a Galveston, Texas, top 40 AM radio station during the summer months following graduation from high school in 1964, and, returning to Austin to begin studies at The University of Texas in September, I applied to Austin’s only top 40 radio station, KNOW, but was turned down as too inexperienced. I made a short demo tape that I sent to other Austin radio stations and eventually KAZZ-FM’s station manager agreed to add a top 40 block to the station’s late afternoon schedule as an experiment. The station was already block programmed, playing different musical genres during different dayparts. Billboard Magazine profiled the station’s odd format in a June 1965 piece that began with “Top 40 music on an FM station? Yes, sir…”, a semi-acknowledgement that KAZZ was among the first, if not the first, U.S. FM station to regularly program rock music.

Would you like to share what was the original concept behind KAZZ? How did you choose artists you wanted to feature and what kind of programme did you do?

KAZZ was the second FM station to launch in Austin, coming online in late 1957. KAZZ’s call letters reflected its original programming format ,full-time jazz with a smattering of swing and big band. Austin, then and now, is a major college town, so KAZZ’s programming was designed to cater to The University of Texas students and faculty. The station struggled financially because FM radio was still new in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, still a novelty, and primarily popular with hi-fi enthusiasts and those who could afford the pricey new receivers. There were no FM radios in automobiles then. By 1964, KAZZ had been sold to a local restaurateur, Monroe Lopez, who wanted to serve Austin’s Latino community by programming Spanish language music and news. However, the station ended up block programmed, in which different genres of music were featured during different dayparts: Spanish in the early morning, followed by the syndicated Grand Ole Opry country hour, and then pop standards and light classical music the rest of the morning, pop standards and showtunes in the afternoon, and folk and jazz segments at night. Only a few months after Lopez bought the station, I arrived with my top 40 program. Each of the station’s announcers, or deejays, specialized in a particular musical genre, so each selected his own playlist. For my part, as the station’s rock ‘n’ roll deejay, I began by programming singles on the Billboard Hot 100. Like other radio stations, KAZZ received free promotional copies of new record releases, but when I began at KAZZ, no record distributors or national labels were sending FM stations top 40 singles, so I had to buy my own copies of the current hits to play on my program. Eventually, many distributors and national labels added us to their promo copy distribution lists, and cartons of new 45s would arrive every week. As we began to receive rock albums alongside singles, I added an occasional album track to my playlist. About a year later, KAZZ added a late night block that featured an eclectic mix of rock, folk, blues, and rhythm ‘n’ blues album tracks rather than top 40 singles. We eventually also added a late night rhythm ‘n’ blues program.

Among the local acts appearing on KAZZ’s live broadcasts are The 13th Floor Elevators, The Sweetarts, Janis Joplin, Jerry Jeff Walker, Allen Damron, Ernie Mae Miller, and Don Dean. What was the counterculture scene in Texas back in the 60s? It’s quite incredible what kind of music was released back then.

I believe it’s been pretty well documented that Austin in the mid ‘60s was a mixed bag of musical styles with quite literally dozens of live music clubs and cabarets – illustrated by the diverse list you’ve just given. Austin is credited by many musicologists as one of the birthplaces of psychedelic rock, and it was likely the 13th Floor Elevators that officially named the genre. By the early ‘70s, Austin also became famous as the birthplace of the progressive or “outlaw” or “cosmic cowboy” country music movement. Austin radio stations in the ‘60s reflected these different tastes: KNOW played top 40 (and was the #1 station in town), KVET and KOKE played country, KTBC and KHFI played pop standards and commercial jazz (but not rock), KFMA played classical, and KAZZ was blocked programmed, as I mentioned before. But as the center of Texas government and politics and home to The University of Texas and many private Christian colleges, Austin also was a mixed bag socially, economically, and politically. At the time, the counterculture was most visible on and around The University of Texas campus, in hippie music venues (most notably the Vulcan Gas Company and its successor, Armadillo World Headquarters), and at head shops (such as Underground City Hall). Austin even had an underground newspaper, The Rag, and an art house movie theater that attracted a counterculture audience. Drug busts were common and, as happened to Roky Erickson and other members of the 13th Floor Elevators, convictions led to heavy fines and prison. Austin also was quartered socially and economically by the Colorado River, which divides the north and south quadrants, and Interstate 35, which divides east and central/west Austin. Generally speaking, the “cedar choppers” – yes, a pejorative term, to be sure, and roughly equivalent to “country bumpkins” – and Latinos populated south Austin (our family lived in south Austin while I was in junior high and high school, so I’m painfully familiar with the term); the more affluent, mostly whites, populated north and west Austin; and African-Americans and Latinos mostly populated east Austin. The capitol and state office buildings and The University of Texas campus dominate, then and today, central Austin.

KAZZ was the only radio station in Austin that regularly broadcast “live” remotes from various night clubs, often four nights a week. The clubs paid for the airtime, so they dictated the musical genre showcased in each remote. Ernie Mae Miller was a favorite at the jazz piano bar in the cellar at The New Orleans Old World Night Club, Don Dean managed the posh Club Seville at the Sheraton Crest Hotel overlooking Town Lake (that portion of the Colorado River that divides north and south Austin) and brought in light jazz and pop standard acts from all over the country (and occasionally international acts, like Bach-Yen). The 11th Door and Chequered Flag featured folk and blues acts. The New Orleans Club, Jade Room, and Club Saracen booked rock acts. KAZZ’s remotes from these venues reflected the diverse tastes of Austin live music patrons. Other popular Austin venues that didn’t present live broadcasts on KAZZ featured country and rhythm ‘n’ blues acts.

“I was on the air when Roky arrived with the test pressing, and I auditioned it while another record was playing.”

You knew Roky of The 13th Floor Elevators.

Roky and I were classmates at Travis High School in south Austin, but I knew him then only casually. It was only after I graduated and began working at KAZZ that I got to know him well. At that point, he was in The Spades. The Spades recorded the original version of Roky’s ‘You’re Gonna Miss Me’. But Tommy Hall recruited Roky to co-found the 13th Floor Elevators, and a month or two later Roky came up to KAZZ with a test pressing of the Elevator’s re-recorded ‘You’re Gonna Miss Me’ that was released on the local Contact label. Tommy Hall’s electric jug distinguishes the Elevators’ version from the Spades’ version. I was on the air when Roky arrived with the test pressing, and I auditioned it while another record was playing. As soon as that record was over, I played ‘You’re Gonna Miss Me’ on air along with a brief live interview with Roky. I’m pretty sure that was the world premiere of the single on radio anywhere. I still have that test pressing.

KAZZ did live broadcasts of the Elevators from The New Orleans Old World Night Club several times, and I hosted most of those using an over-the-top and, in retrospect ,quite silly top 40 deejay delivery. Recordings of many of those broadcasts have been officially released, bootlegged, and torrented around the world. There may be a couple of recorded KAZZ Elevators broadcasts that remain unreleased, perhaps because they’ve been lost or hoarded. The copies in the Sonobeat library are sourced from the station’s tapes (KAZZ used a 3 second tape delay in order to give the studio announcer time to prevent any of the “seven dirty words” from accidentally airing, so all of our remotes were recorded, although few tapes were retained) or from off-the-air recordings by Sonobeat friend Ralph Y. Michaels.

The 13th Floor Elevators are now considered as one of the pioneering acts of psychedelic rock, predating other West Coast bands. They must have been quite a shock for a regular listener back in the sixties?

Totally unique sound and lyrics. To some, a shock, especially in-your-face lyrics like “After you trip, life opens up” from ‘Roller Coaster’. To others, a welcome and, perhaps, delightfully scurrilous alternative to bubble gum rock. And to still others, a mind-blowing awakening. So much has been written about the Elevators and their cultural and musical impact and influence. In my view, the most complete story of the Elevators is by Paul Drummond, who served for years as the band’s official archivist and whose two books – one a narrative history and the other a pictorial history – are definitive. Disclosure: Paul’s a longtime friend of Sonobeat, and we helped source materials for his 13th Floor Elevators: A Visual History, published last year. And, of course, you’ve covered the Elevators here at It’s Psychedelic Baby Magazine.

A typical Roky Erickson pose (you’ll see it in many photos of him performing); this one taken in March 1966 at the the Teodar Jackson Benefit at the Austin Methodist Center alongside lead guitarist Stacy Sutherland and drummer John Ike Walton

So basically the formation of Sonobeat is a natural extension of KAZZ’s live remote broadcasts?

Yes. The remote broadcasts were created as a way to increase station revenue, and through the live music remotes Dad, who was KAZZ’s sales manager when we launched the remotes, and I met dozens of acts and their managers. The remotes were our entrée to unsigned singers, songwriters, and bands and, because we did all these remotes from night clubs, we also got to know the club owners and managers. When we launched Sonobeat, we couldn’t afford to build and outfit a recording studio, so through our friendships with those owners and managers, we were able to use some of those night clubs as makeshift recording studios.

What’s the secret behind the moniker of “Rim Kelley”?

Not an exotic story. When I began working in radio, most deejays used “air names” in the same way so many movie stars choose memorable professional names rather than using their real names (think Marilyn Monroe, whose real name was Norma Jeane Mortenson, or Bruno Mars, whose real name is Peter Gene Hernandez, or any of the past and current crop of rap stars). Dad suggested I, too, choose an “air name”, so I wrote surnames I liked on slips of paper and threw them into a hat. The one I randomly pulled was stuck in the rim of the hat. The name on the slip was Kelly, which I had included to honor cartoonist Walt Kelly, whose Pogo newspaper comic strip was one of my favorites. I revised the spelling from Kelly to Kelley. And, since that surname slip had been pulled from the hat’s rim, I adopted “Rim” as my first name. Rim Kelley. There it was.

“The concept of starting an Austin-based record label sprang from all the musical acts we broadcast on the KAZZ remotes.”

Can you elaborate the formation of Sonobeat?

The concept of starting an Austin-based record label sprang from all the musical acts we broadcast on the KAZZ remotes. There was no independent label in Austin at the time, although Austin Custom Records offered vanity recording and pressing services that acts had to pay for themselves. It was truly rare for an Austin-based act to get picked up by a regional or national label, so for most that wanted to release a single, the only choice was Austin Custom Records. We wanted to change that by financing the recording sessions and record pressing and distribution ourselves, not at the artists’ expense. As we started out, we recorded covers by jazz and pop acts, such as the Lee Arlano Trio, Don Dean, and Fran Nelson, but Dad and I both considered original songs to be a foundation for the success we hoped to achieve in the record business. Our local rock bands were beginning to write their own material to supplement the top 40 covers they performed. Among the first bands we recorded that wrote original material were Leo and the Prophets (who were one-hit-wonders with ‘Tilt-A-Whirl’ on the short-lived Totem label) and the Sweetarts (who had recorded one single for the Dallas, Texas-based Vandan label a year earlier). So, initially we pursued two directions: acts like the Arlano Trio and Don Dean covering jazz and pop standards and acts like Leo and the Prophets and the Sweetarts recording only original songs. The original songs provided an opportunity to launch our music publishing company, Sonosong, alongside the Sonobeat label.

There were other factors we considered while planning Sonobeat’s launch, including how expensive it would be to buy new equipment and set up a permanent studio facility versus borrowing microphones and tape decks from KAZZ and renting night clubs during off-hours to use as remote recording studios. Like so much that was going on in music during the mid- to late-‘60s, things coalesced in a serendipitous way – getting to know acts and their managers by spotlighting them on KAZZ, having alternatives to launch without investing in expensive recording equipment and a permanent studio, being able to add a music publishing subsidiary, and having some ideas about how a small local outfit could compete in a crowded record label marketplace dominated by a handful of majors.

During its early years, Sonobeat had no recording studio of its own, so it rented Austin-area night clubs during off hours. What did that look like?

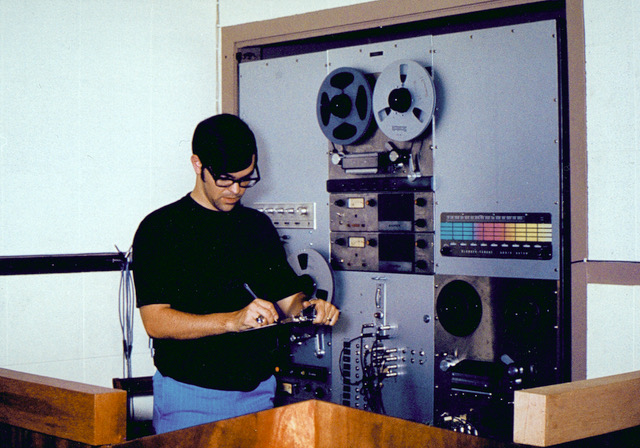

Despite having to transport our equipment to different night clubs for recording sessions, often several times a week, that really was the easy part of launching Sonobeat, since we knew the club owners and managers and, in some cases, they were happy to let us use their clubs gratis during off hours. We built wood frames to transport KAZZ’s Ampex 2-track tape decks and packed microphones, headphones, and cables into suitcases. KAZZ’s chief engineer built a portable battery-powered stereo mixer for us, which we set up on a card table. And off we went from location to location, session to session. The acts seemed to feel comfortable recording in the night clubs where they regularly performed, although our sessions were held without live audiences.

Can you name a few clubs?

We actually used more than just night clubs, but those we did use were The Action Club for its spacious dance floor (where the bands set up for our recording sessions), The Club Seville (used only for our jazz and pop recording sessions), and The Vulcan Gas Company (with its huge acoustics, but not all bands liked the boominess of the room). We also used a parking lot at The Lake Austin Inn and the auditorium at First Cumberland Presbyterian Church (which housed a full-sized basketball court and had a high ceiling like The Vulcan Gas Company’s, giving it interesting acoustics). We recorded one single – our only live recording – at an in-the-round stage at the youth pavilion at Hemisfair ’68, the world’s fair in San Antonio, Texas.

I believe KAZZ’s chief engineer Bill Curtis had an important role at the beginning of Sonobeat?

Yes, Bill, who was also a Travis High School classmate, although a year (or perhaps two) behind me, was an electronics whiz kid. When we began planning Sonobeat, Dad and I priced audio mixing consoles, but they were just too expensive for a tiny startup like ours. Bill Curtis, who at the time was KAZZ’s chief engineer, told us about a new type of low-power, low-noise, and, perhaps most importantly, low-cost transistor – a field effect transistor, or FET – that would be perfect for building microphone pre-amps and mixer circuits. So, he put together a small 6-input stereo mixer, housed in a wooden box with a metal faceplate on which the volume and pan control knobs were mounted. It was battery-powered and portable. And, once Bill got a few glitches worked out of the circuit design, it was a workhorse for us for the first couple of years. Bill also served as co-recording engineer with me on our early sessions with Leo and the Prophets, the Arlano Trio, and Fran Nelson.

“The most important was to record and release all our 45 RPM singles in stereo.”

What are some important audio decisions you made?

The most important was to record and release all our 45 RPM singles in stereo. That decision created a domino effect of other audio decisions, the most significant being how to record and mix a rock track in stereo (I had absolutely no idea) and, less significant but still important, what record manufacturing plant could master and press 45 RPM stereo singles, since they weren’t a thing then.

At the time stereo became popular. If you look back, what’s your opinion about it? Stereo vs Mono from your perspective?

Stereo albums were popular in the ‘60s, mostly for pop, jazz, and classical releases but not so much for rock, blues, and R&B, but, as I said, stereo 45s were not a thing then. The major labels had dabbled in stereo 45s early in the ‘60s but abandoned them because only a tiny fraction of teens and twenty-somethings, who were the target audience for singles sales, owned stereo record players. Looking back with 20/20 hindsight (and I’m not referring to the year just past!), our decision to release our 45 RPM singles only in stereo wasn’t really smart at the time. We were looking for a way to distinguish our label from all the others – a gimmick that would attract attention and, hopefully, encourage sales. Turns out, when we started out, it was far easier to record and mix a mono track than a stereo track, and far harder to master and press a stereo 45 than a mono 45.Worse still, AM radio stations, the most essential tool to promote sales of rock singles, weren’t outfitted with stereo equipment because they were limited technologically to monaural broadcasting. The decision to go “all stereo” finally worked to our advantage when we broke open the catalog for digital reissues in 2014, but back in 1967, ’68, ’69, stereo singles took more time and money and got less airplay than we originally thought they would. I’m glad I don’t have to go back and rethink that decision!

You started researching stereo recording and mastering techniques.

I’ve been interested in tech going back to the Tom Swift Jr. teen inventor adventure book series of the 1950s and ‘60s. Working in radio, starting in 1964, gave me a background in audio and, in a very limited sense, mixing concepts, but when we started thinking about launching a record company, I hit The University of Texas library for books and magazines on recording techniques. As a radio-TV-film undergrad major at UT, I also was able to ask some of my professors for guidance. The reality is, regardless what you read about stereo recording and mastering, you learn by doing, so what I gleaned from books and magazines served only as starting points. Our real research was trial and error in actual recording sessions and feedback from the record pressing plant mastering engineers.

One technique I would like to highlight is reducing distortion via mastering lacquers at half speed.

That was a technical suggestion we were given when we began interviewing record pressing plants. Houston Records, that mastered and pressed our singles for the first year, was able to cut stereo lacquer masters (used to make the record pressing plates) at half speed to get a clean groove with minimal loss of low-end, pretty faithful high-end, and a relatively wide dynamic range. That said, we were never completely satisfied with Houston Records’ mastering and a year later switched to Sidney J. Wakefield in Phoenix, Arizona. Wakefield was a high-end record manufacturer and cost more than Houston Records, but, again, we wanted our 45 RPM singles to sound great in order to stand out and make a positive impression, especially with reviewers and radio station program directors.

Wakefield had state of the art Scully lathes and cutting heads fed by custom super-powered amps, were experts at half-speed mastering (which they had developed to master high fidelity and high dynamic range classical and jazz albums) and used an ultra-high quality but expensive vinyl compound to press the records. Comparing Houston Records’ mastering and pressing with Wakefield’s mastering and pressing, I think you do hear a difference, Wakefield’s being a little cleaner, with greater fidelity and no groove skipping, but I doubt the consumers who bought our records noticed or cared.

Another technique is to center bass and kick drums.

A must for stereo 45s. We were told to mix bass, kick, and low toms to the center by Houston Records’ mastering engineer when we first interviewed pressing plants. Because of how stereo grooves are cut, the record player tone arm tracks poorly and can skip and skate when bass and kick are mixed to the left or right. And low frequencies mixed to the extreme left or right are half as loud as when mixed to center.

Can you name the majority equipment used?

We started with ElectroVoice 665 dynamic microphones and two Ampex quarter-inch 2-track tape decks, one a 350 and the other a 354, all borrowed from KAZZ. Our first recordings were made using the Bill Curtis 6-channel stereo mixer. We used inexpensive Radio Shack audio amplifiers to drive the headphones I wore while “live” mixing a session and that the singers and musicians wore when overdubbing their vocals and additional instrumentation. I don’t recall the headphone brand, but they were over-the-ear cup models. We had six pairs of headphones, I believe. We splurged on two sets of top-of-the-line speakers that we used for playback and, when we finally had a home-based studio, for mix-downs. We had no audio compression or equalization equipment when we started out, so there’s a noticeable difference in the sonics and dynamic range of our 1967 and early ’68 recordings compared to recording seven just a year later. Within a few months after launch, we bought a pair of used Thompson Stanford-Omega condenser microphones, which we’d intended to use to mike drum kits, but one of the pair almost immediately developed a ground fault hum that even Bill Curtis couldn’t fix, rendering that mike unusable. Because we bought the pair used, they couldn’t be returned, so we used the remaining Omega for vocal overdubs. Within a year after launch, we bought an Ampex AG350 solid state 2-track tape deck, two ElectroVoice Slimair 636 dynamic microphones, and a matched pair of Sony ECM22 electret condenser microphones. By mid-1968, we acquired a half-inch 4-track Scully tape deck and built a large steel plate reverb modeled after the famous EMT 140 used at Abbey Road Studios. In ‘68, we built a 10-channel stereo mixer housed in a Samsonite suitcase for portability, which replaced the Curtis 6-channel mixer, and added a Fairchild Lumiten 663ST optical compressor and a Blonder-Tongue Audio Baton 9-band stereo graphic equalizer. At the end of 1968, we added a half-inch 4-track Stemco tape deck, basically a refurbished Ampex transport with Stemco’s custom solid-state electronics. At the same time, we bought a 6-channel Gately PM-1 stereo mixer in an attaché case to side-chain into the 10-channel suitcase mixer. At the beginning of 1970, we built our third and final custom mixing console, this one a 16-input, multi-channel 3-piece unit, and rack-mounted the tape decks, compressor, graphic equalizer, and added a patch bay. After Dad relocated the studio to Liberty Hill, Texas (about 35 miles from Austin) in 1973, he acquired some additional equipment, including a Dokorder 7140 quarter-inch 4-track tape deck, a second Blonder-Tongue Audio Baton graphic equalizer, a vintage vacuum tube stereo limiter, and set of large monitor speakers.

And by the end of 1967 you were recording a lot! What are some highlights?

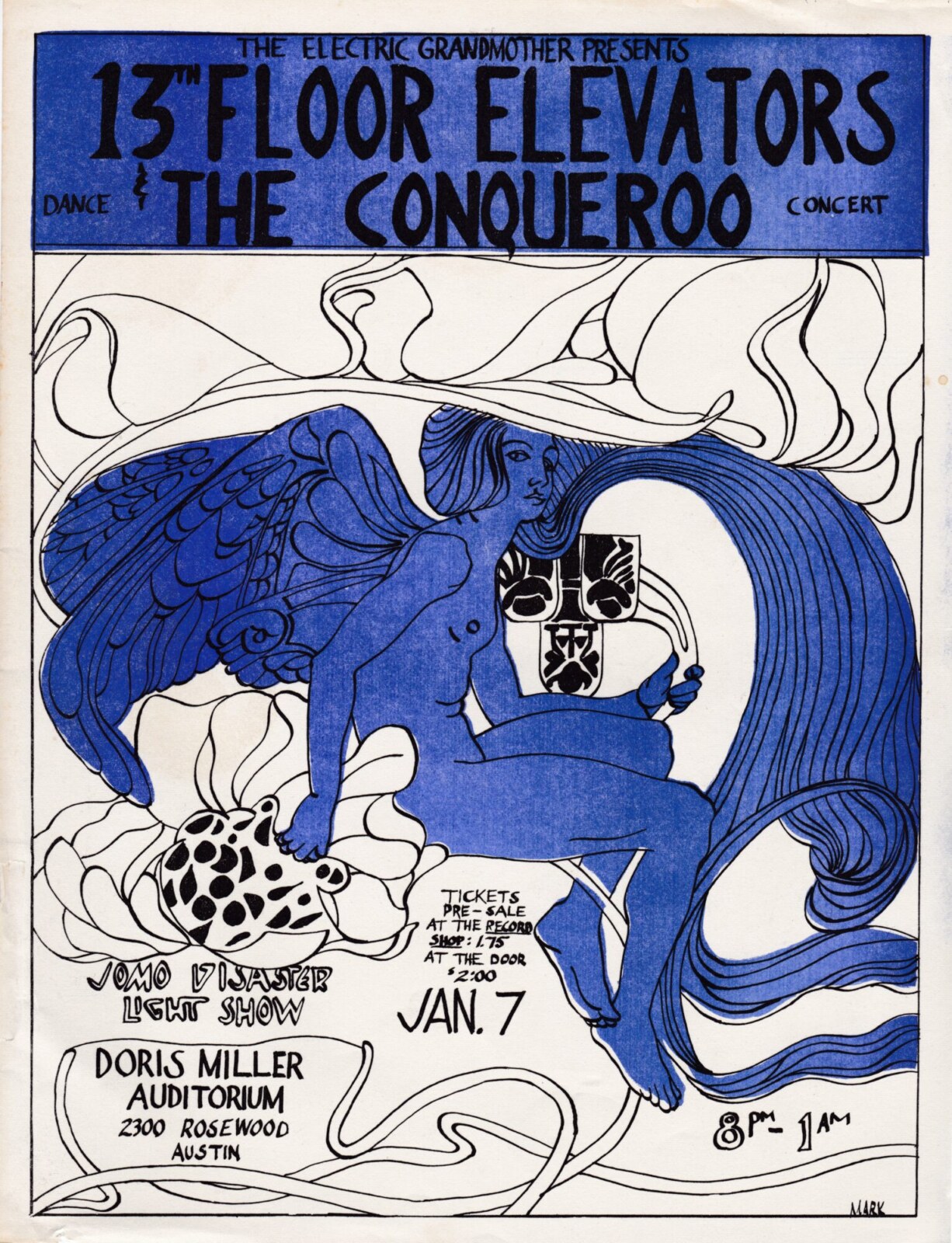

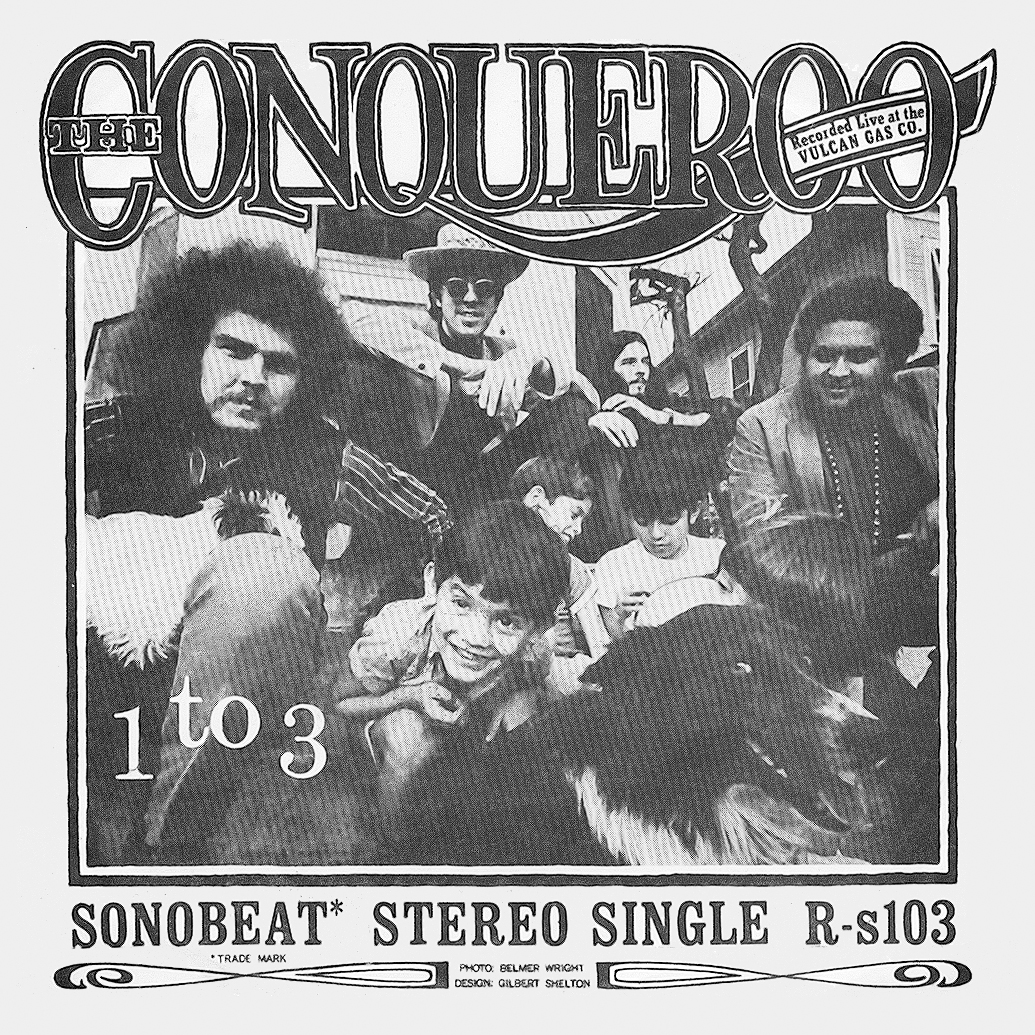

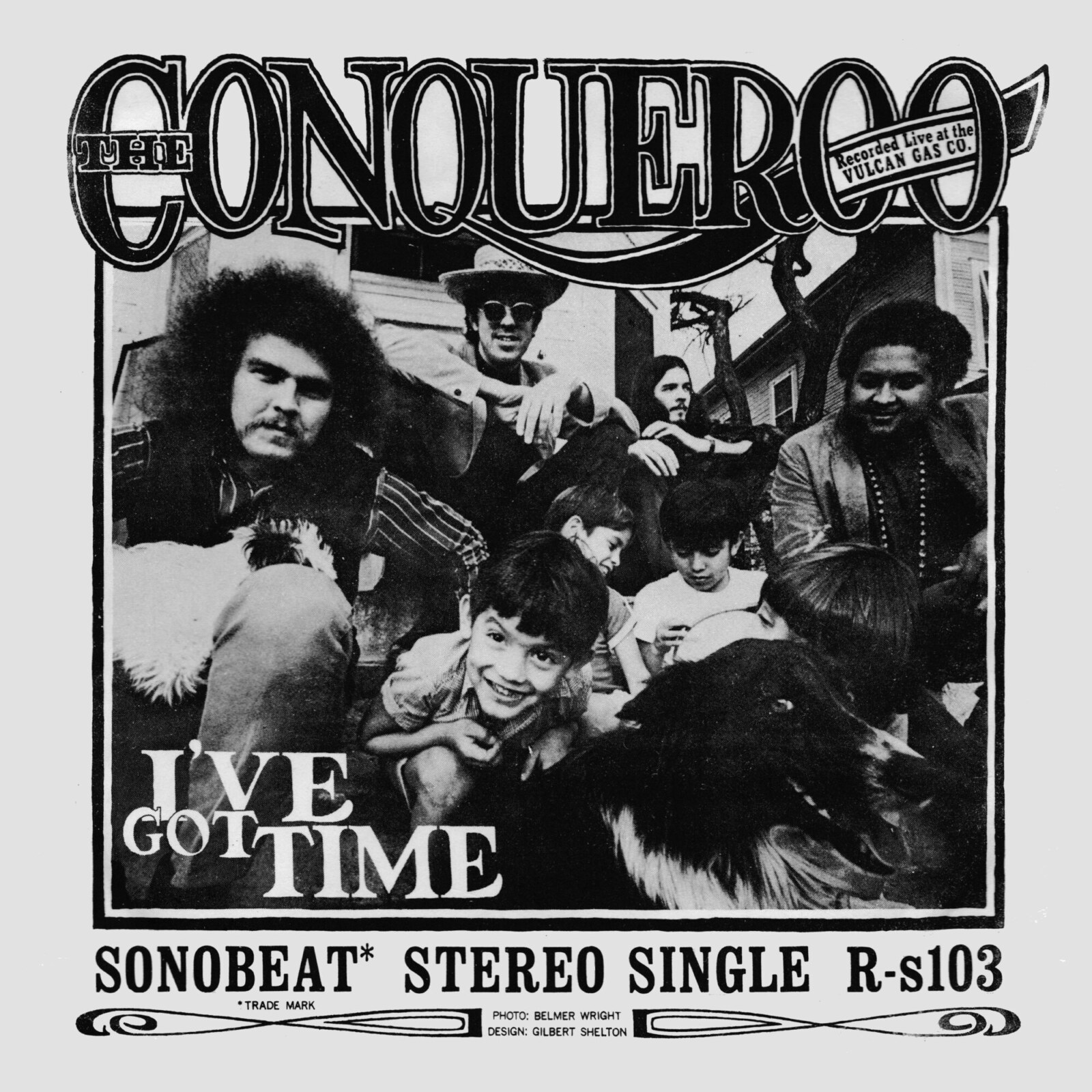

After overcoming a few technical hiccups with the Curtis homemade mixer, I was satisfied with the recordings we did early on. We would have released Leo and the Prophets as our first single, but the band had only one finished original song. The Sweetarts single remains one of my favorites, not just because it was our first release but as much because Ernie Gammage’s original songs have memorable hooks, catchy melodies, and really interesting lyrics. The band was tight, too! Lavender Hill Express was Austin’s first “super group” of the ‘60s, rising like a phoenix from the ashes of two of Austin’s hottest club and frat bands that had broken up in ’67. Lavender Hill Express recorded three singles for us, the most by any act we recorded, and each was musically different. Lavender Hill Express’s first single, ‘Visions’ backed with ‘Trying To Live A Life’, remains a favorite because it features a string quartet and harpsichord overdub. We felt with that single we were finally beginning to offer releases competitive with the major labels. Wali and the Afro-Caravan – we recorded the group’s single at the youth pavilion at Hemisfair ’68 in San Antonio and the group’s album in our living room (!) – were a joy to work with because of the group’s selection of compelling percussion-based material and the energy every musician put into every piece. The Conqueroo was fantastic to record, and our digitally restored and remastered reissue of ‘1 To 3′ and’ I’ve Got Time’ in October 2020 showcases the strong musical and vocal talents of one of Austin’s seminal psych groups that, by the way, slightly pre-dated the Elevators. We received a positive review of our Conqueroo reissue in the January 2021 issue (#111) of Shindig! magazine.

Plymouth Rock’s 1969 single featured a well-crafted pair of songs and performances, but I was challenged to get a stereo mix from the 4-track intermediate master that had been bounced down from the 4-track session master in order to add two overdub tracks.Breaking with our “stereo only” tradition, we released that single only in a monaural version. Analog equipment back in the ‘60s and ‘70s was limiting, and while I liked the mono mix, which had a lot of punch, a stereo mix had to wait until modern digital music workstations made it possible to separate the 4-track master into stems and sub-stems.We finally were able to create a stereo mix for our 2019 digital reissue. Our only truly country single, by Ronnie and the West Winds, also was fun to record. The West Wind’s “B” side, an instrumental entitled Windy Blues, was the shortest song we commercially released, running only 85 seconds. Ronnie and the band were high school studentswhen we recorded them but already showed great talent and poise.

I should also mention that the Lee Arlano Trio’s pop jazz album that we recorded when we first started in 1967 and released in 1968 was relatively easy because there were no amplified instruments and no vocals.

That made the sessions simple to set up, record, and mix (we used only 6 microphones). Every member of the trio was a master of his instrument, so almost every track on the album was recorded in a single take. And, because there are zero recording tricks or techniques applied, you hear the trio’s sheer talent come through. James Polk and the Brothers’ funk single ‘Stick-To-It-Tive-Ness’ also is a favorite, and it was among the first recorded entirely in our small home-based studio that we set up in mid-’68. Singles by Don Dean, Fran Nelson, and Jim Chesnut gave us an opportunity to produce more traditional pop tracks. We released a drum solo by Vince Mariani, which served as a precursor to our Mariani progressive rock recordings. Despite the fact that Vince is a spectacular drummer, I really can’t explain today why we thought then that a drum solo single would sell! It didn’t.

As we moved into ’69 and ’70, with experience and better equipment, we started experimenting more. I can’t think of any act or recording session I produced or engineered that I didn’t like and enjoy. I left to attend law school in Houston, Texas, at the end of summer ’70, so Dad continued on his own and branched out into other musical genres, including folk, country, and even gospel. He also went through a period in 1971 and ’72 in which he experimented extensively with quadraphonic recording techniques, and I helped him design quad mixing modules that he added to the 16-track console we had built in 1970.

Was there any certain key on which you picked rock groups?

In no particular order: tight, well-rehearsed musicianship; strong and on-pitch vocals; original songs with a hook and compelling lyrics; nice people to work with.

Bill Josey Sr.’s sadly passed in September 1976. What happened next?

That really was the end of Sonobeat as an active company. The tape library, session notes, photos, documentation… all were stored away and largely forgotten for years. Although brother Jack has tended the archives since the mid-‘80s, it wasn’t until the early 2000s that he began to catalog and digitize the masters.

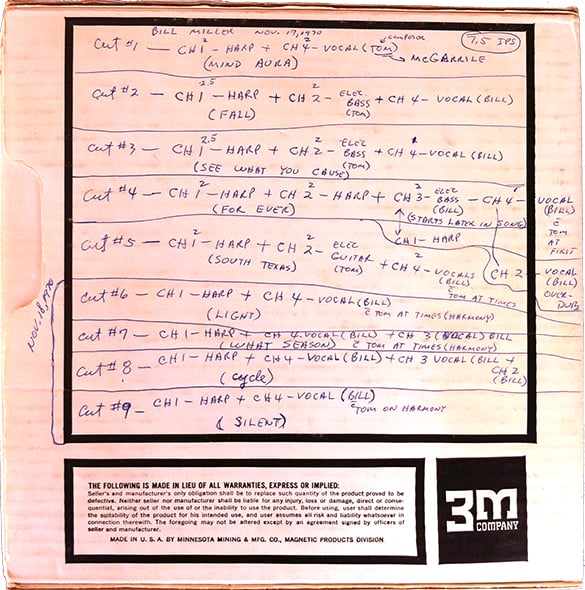

“There are a bit over 200 tape reels in the library”

How big is the master tape library? Is everything now transferred to digital?

There are a bit over 200 tape reels in the library, and each reel contains anywhere from one to a dozen individual tracks, including false starts, outtakes, and alternate versions here and there. The tapes were in storage for quite a long time before we started to digitize, and Jack had to physically repair many before they could be played. Our early recordings were made on Ampex 201 acetate tape stock from which, literally, the magnetic oxide has flaked off, so, no, not all material has been transferred to digital and some likely never will be as many of those early recordings are too damaged to repair. We’re told that acetate tape stock can’t be “baked” to repair the so-called “sticky-shed syndrome”. We also passed over a dozen or so tapes when originally digitizing because they were not clearly marked as Sonobeat masters. Eventually, we’ll get back to those to see what’s actually on them. Who knows, we might find one of those lost KAZZ broadcasts of the Elevators!

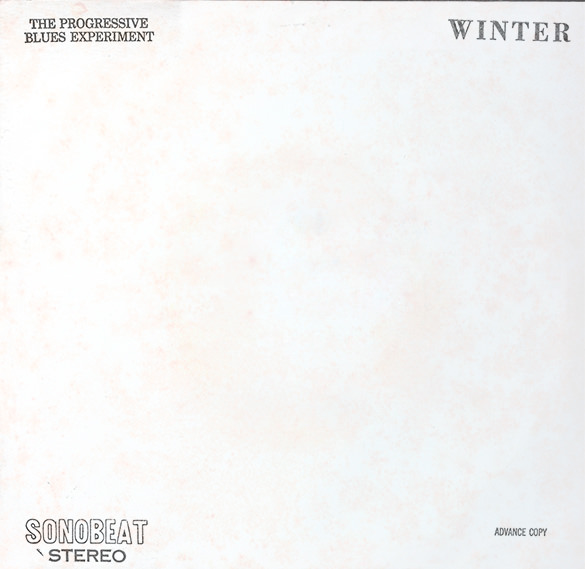

Sonobeat albums such as Mariani, David Flack Quorum, Wali and the Afro-Caravan, Johnny Winter, and Cold Sun; vinyl singles by Lavender Hill Express, Sweetarts, The Conqueroo, The Thingies, Wali and The Afro-Caravan, and Plymouth Rock; and Sonobeat’s song demo albums by Herman Nelson and Bill Wilson, bring extraordinary prices among collectors. What do you recall from working with Cold Sun, Mariani, Johnny Winter, The Conqueroo? I think Cold Sun’s recordings are right next to 13th Floor Elevators. What do you think?

First, we deeply appreciate that collectors find Sonobeat recordings worthy of collecting. We recorded acts and music we loved, and never thought of building a library or creating any sort of legacy at the time. The record business back then was based on maximizing the income from short-lived hits. Artists were only as good as their last hit and, because of that, one-hit-wonders abounded.

We were painfully aware of this churn, and groups we recorded broke up, re-formed, and broke up again with regularity. In some cases, records we were about to release ended up shelved because the group disbanded before we could get the record pressed. For regional releases, we needed the band to promote the single, so if the band had broken up, there was no point in investing in a release. For collectors to invest in vinyl Sonobeat singles and albums today always surprises me.

It’s a tribute to the musicianship and songwriting skills of Austin musicians living and working in a stimulating place and time.

To be sure, much of the interest in Sonobeat records today is based on Austin’s ascension to “live music capital of the world” since the ‘70s, to the number of ‘60s Austin musicians who went on to greater fame, and to the popularity of Austin City Limits and the annual SXSW festival.

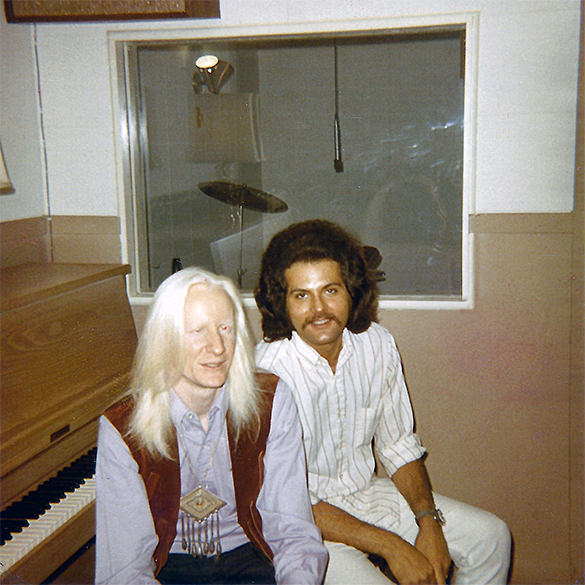

In January 2014, History Press published Ricky Stein’s Sonobeat Records: Pioneering the Austin Sound in the ’60s. How was to work with Ricky Stein? I guess this book is the most comprehensive guide to Sonobeat?

Ricky’s book is an expansion of his American Studies thesis that he wrote as an undergrad at The University of Texas. A mutual friend suggested he research Sonobeat as a potential topic for his thesis, so Ricky reached out to us. We gave him permission to use anything on the Sonobeat website he wanted and provided email addresses for artists we recorded who we’d kept in touch with over the years. He interviewed brother Jack and me, but to Ricky’s credit, he also interviewed dozens of singers, songwriters, and musicians we recorded as well as others in the Austin music scene during the ‘60s. Ostensibly the story of Sonobeat Records, Ricky’s book is really a portrait of a seminal era in Austin music and gives the deserved credit to the musicians who made the scene so rich and diverse. Sonobeat was just lucky to be there to capture a bit of that era on tape. I reviewed Ricky’s manuscript but corrected only factual errors – names, dates, places – leaving his narrative alone. When Ricky told us he’d gotten a deal to expand his thesis into a book, I was quite surprised. Who would care about a tiny Austin record company with a lifespan less than a decade and a total commercial output of only 24 singles and 5 albums? I’m still honored and thrilled that Ricky chose Sonobeat as the vessel for his story of the rising Austin music scene in the mid-to-late ‘60s.

In March 2014, Sonobeat Historical Archives began a series of digital reissues of select material. I would love it if you can tell us more about this?

Over the years, especially after we launched the Sonobeat website in 2004, we’ve been approached by specialty record labels seeking licenses to reissue specific Sonobeat recordings, but we’ve always resisted, desiring to manage reissues from the library ourselves. A few years before Ricky Stein’s book came out in 2014, we discussed reissues with Ernie Gammage of the Sweetarts and Layton DePenning of Lavender Hill Express, but we were thinking about vinyl reissues, which we would have had to fund out of our own pockets with no certainty we’d ever earn back the costs. Still, it was a compelling idea, and we believed some of Austin’s iconic record shops, such as Antone’s and Waterloo Records, might be able to sell a few hundred copies of each reissue. But years passed without our taking any action, perhaps because we were busy with full-time jobs and didn’t have the time or resources to attack a reissue program for Sonobeat’s library. By 2014, when Ricky’s book came out, Apple’s iTunes’ digital distribution model, which had launched more than a dozen years earlier, was mature and phonograph record sales were waning, so we switched our thought process from far more time consuming and expensive vinyl releases to far less expensive digital releases. We worked with Ernie Gammage and all members of the Sweetarts to bring them onboard – well, they had been ready for years for us to reissue their single – and began digitally restoring and remastering ‘A Picture Of Me’ and ‘Without You’. We want the artists and, particularly, the composers of the bands’ original songs to be part of the decision-making process. Next, we began talking with Layton DePenning and all the living members of Lavender Hill Express about reissuing the band’s three Sonobeat singles. That led to our reissuing not just all three of the singles but also a previously-unreleased track, ‘Trouble’, written by band co-founder Rusty Wier, which we issued as part of the Lavender Hill Express digital EP with the blessing of Rusty’s son Bon. Same with the Plymouth Rock and The Conqueroo reissues; the artists and composers were part of the decision-making process. The only exception to this process so far was our reissue of the Lee Arlano Trio single and album, all of which consist of covers of jazz standards that were available to us under the U.S. Copyright compulsory license system. Lee had died many years earlier, and since we own the masters, we simply reissued those tracks.

On October 30, 2020, Sonobeat Historical Archives reissues the highly-anticipated restored and remastered digital edition of The Conqueroo’s 1968 Sonobeat single. What’s the story behind these recordings?

I had really wanted to reissue The Conqueroo’s Sonobeat single going back to 2014, when we reissued the Sweetarts’ single, but I didn’t know where any of the band members were. The Conqueroo tracks also posed a technical challenge, having been recorded at The Vulcan Gas Company on the 2-track Ampex 350 and bounced for vocal overdubs, which occurred in the same session at the Vulcan as the recording of the basic instrumental tracks, to a 2-track Ampex 354. The dynamic range of both tracks is crazy wide with occasionally overpowering bass guitar and huge volume swings in the vocals. The tracks gave the Houston Records mastering engineer fits and ended up highly equalized and compressed on the 1968 vinyl single release. In 2019, we got an out-of-the-blue email from Bob Simmons, who was working on a documentary film called The Poster Boys about, what else, Austin concert poster artists of the ‘60s and ‘70s. Some of the most famous Vulcan Gas Company posters – in the same artistic vein as the psychedelic posters of The Fillmore in San Francisco during the same time period – feature The Conqueroo. Bob wanted permission to use excerpts from The Conqueroo’s single in the documentary’s soundtrack and said both Ed Guinn and Bob Brown, who wrote the songs and were members of the band, were onboard. Through Simmons, we connected with Ed and Bob and worked out a reissue arrangement and, of course, permitted Bob to use the masters in the documentary’s soundtrack.

But backing up a few decades. Although KAZZ never originated any remote broadcasts from the Vulcan Gas Company, Dad and I made the club circuit a couple of times a week, and the Vulcan was always one of our regular stops because it booked really interesting acts. The Conqueroo were favorites there and the de facto house band. But I first met the band when I emcee’d an Elevators concert at Austin’s Doris Miller Auditorium with The Conqueroos the opening act. I pretty much just walked up to them after the show and asked if they wanted to record with Sonobeat. We did a late ’67 session but shelved those tracks, returning for early ’68 sessions that yielded the tracks on the single. All were recorded at the Vulcan, and although the single sleeve says “Recorded Live at the The Vulcan Gas Co.”, the tracks actually weren’t recorded before a live audience but were merely “live mixed” in stereo to a 2-track tape deck, such that there was no ability to remix the tracks once printed. Now back to 2020… it was more than a year after working out a reissue arrangement with Ed and Bob that we finished a complicated restoration and remaster made possible by today’s digital audio technologies. Jack made an 88.2KHz/24 bit transfer of the master tape. He then cleaned up distortion, clicks, hum, and other artifacts on the digital transfer using iZotope’s RX7 and RX8, after which we remastered using half a dozen audio processing plug-ins inside Adobe Audition and Logic Pro, finishing up with iZotope’s Ozone 9. We were surprised and pleased that Shindig! magazine reviewed our reissue in its January 2021 issue and especially proud that the reviewer ended by saying “These two tracks have been expertly re-mastered from the original tapes for digital release.” We did the restoration and remastering completely in-house, and it took weeks that seemed like forever.

Any sense of direction for your next venture?

We’re considering issuing previously unreleased material in the archives, including songs by progressive rock bands Genesee, Georgetown Medical Band, and New Atlantis, who we recorded in the late ‘60s. You can get a taste of their songs on the Sonobeat website. We’re also considering a vinyl compilation album. We’ve been fortunate to reconnect with so many of the musicians and songwriters we worked with back then and know they’re also game for digital release of their Sonobeat recordings.

How are you coping with the current world pandemic?

I’m semi-retired and able to work from my home office. My brother and I collaborate via phone, email, and Dropbox when we’re prepping a new digital reissue. Maintaining and enhancing the Sonobeat website also is easy from my home office. I’m particularly thankful for the health care workers who’ve been saving lives during this catastrophic pandemic. I’m also thankful for other essential workers whose jobs can’t be performed from the relative safety of home. Like most, I’m frustrated by being isolated from family, friends, and colleagues, but we now sense the proverbial light at the end of the tunnel. Maybe if we all listen to a little more music, this challenging period will pass more quickly?

The whole music industry is struggling. Do you think there will be a fresh wave of excitement when all this is over and the live music will be stronger than ever?

Music isn’t going away and seeing and hearing a favorite artist in person at a great venue, whether it’s the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles, Wembley in London, the Zapata Café Bar in Berlin, the Sydney Opera House, or the coffeehouse down the street from wherever you live, will always be an exhilarating way to enjoy music. It seems certain live music will rebound, but I think it’ll be a slow recovery and, at least for the immediate future, the experience probably will be a lot different at larger venues. If vaccines and social responsibility eradicate the coronavirus in the coming months, live music should see a return to cautious normalcy.

“Nostalgia sells, like comfort food”

There seems to be more interest in reissues lately than in new music.

Nostalgia sells, like comfort food. Today’s digital technology makes reissues relatively easy and inexpensive: no inventory to manufacture and distribute. But the same technology seems to me to financially imperil the creation of new music. Streaming, which has replaced almost all income from physical and digital record sales, pays so little that even top artists might not want to start over from scratch today. That said, I like revisiting the music of my teens and twenties, so I see how reissues can be compelling, especially on digital platforms, where they’re easy to find and legal to download and stream. Fortunately, there’s still new music coming out every week, and lots of new artists to discover. Let’s hope they can survive by creating imaginative new ways to monetize their music and performances.

Have you found something new lately you would like to recommend to our readers?

We listen to a lot of new music via Apple Music, Spotify, Sirius XM, and new movie and TV series soundtracks. I’m happy to hear new releases by artists I’ve loved for decades, like Alan Parsons, Paul McCartney, Bruce Springsteen, and, more recently, Taylor Swift. But there are plenty of talented new artists putting out compelling sounds across every musical genre, in fact far too many to name or recommend. We have overwhelming choices now for new music discovery. I’m just as apt to listen to Max Richter’s newest electronica as to a hot new K-Pop act, the Mandalorian soundtrack, a ballad by Bruno Mars, or an alt track by Billie Eilish, but none of us can listen to everything, and I’m not yet ready to trust AI’s suggestion of music that it thinks I’ll like. Even with the power of social media’s tastemakers to help promote them, independent acts, without the major record companies’ promotion money and machinery behind them, will struggle to find a deserved audience large enough to make music a viable career, but at least there’s no end to the talented singers, songwriters, and musicians willing to give it a try.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Thanks, Klemen, for inviting me to share some of Sonobeat’s background with It’s Psychedelic Baby Magazine readers. Austin’s music legacy is rich and diverse, and there seems no end to the quality talent emerging from The Live Music Capital of the World. We were happy to be there at its beginnings and to add to its legacy.

Klemen Breznikar

Sonobeat Records Official Website / Twitter

Mike Jensen shares his memories of Roky Erickson of the 13th Floor Elevators

Thank you for this unusual and interesting Interview. And also for the unknown Photos !!