Shimmy-Disc’s Kramer on Crafting Ambient Sound and Finding Beauty in Silence

The air shifts, thick with an almost sacred hush, as Kramer, the enigmatic figure behind Shimmy-Disc, reflects on the genesis of his peculiar world.

Though his name echoes through the halls of independent music, a champion of its wild heart, his beginnings whisper of a more ordered realm. His story starts somewhere quieter. As a young organist, he chased structure and form, drawn to the clean lines of classical sound. Then the Beatles arrived, and everything cracked open. Yet, it was not the bright, fleeting notes of mainstream pop that truly reshaped his spirit. No, the revelations came on quieter currents: Leonard Cohen’s crystalline poetry, the hypnotic repetition of Terry Riley, and the layered territories forged by Fripp and Eno. But it was Gavin Bryars’ ‘The Sinking of the Titanic’ that truly etched itself upon his soul, a profound and lingering impression, a high-water mark against which all else is still measured. Indeed, he muses, all creative paths, in their circuitous wanderings, ultimately converge upon the tranquil garden of Brian Eno.

In an era built on speed and output, Kramer moves in the opposite direction. He listens for silence. He follows feeling over theory, intuition over control. Like John Cage or Pauline Oliveros, he treats silence not as absence but as a starting point and an ending, something complete in itself. In that silence, he finds room to wander. Reverb becomes more than a studio effect. It becomes a kind of opening, a quiet invitation to hear differently.

The studio, for him, is no mere instrument, no cold collection of wires, but a living, breathing partner. Kramer’s fingers, delicate as a lover’s, trace the contours of the mixing console, coaxing sound towards its inherent beauty. For in this ephemeral world, beauty, he firmly believes, remains the only protest worth uttering. Age has softened him, and his work now seeks peace. Even when the music holds tension, it comes with tenderness.

He has slowly shifted away from language and into sound itself. But even there, he is still searching for emotional truth. His ambient compositions, like moonlit dreams, blur the boundaries between reality and imagination, offering those who listen a new, exquisite way to feel. They invite the listener to cross the thin line between what’s real and what’s imagined. If you let them, they might show you parts of yourself you didn’t know were there. For Kramer, music is no longer a product. It is a conversation. One that doesn’t end when the song does.

“Beauty is the only valid form of protest in the world we are living in today.”

I’d love to begin at the root of things. What sounds filled your childhood? Was there a particular record or moment that first unsettled the air around you, that made music feel like something other than entertainment… something mysterious, perhaps even sacred? And do those early impressions still echo in the work you do today, or has your relationship to sound moved elsewhere, into other forms?

Kramer: The Beatles is where it all started, in terms of “pop” music, though I was a classical organist striving for perfection by the time I was eight years old. It took a while for The Beatles to become more than just a curiosity for me. ‘Pet Sounds.’ The Zombies. I remember having an epiphany while listening to the early songs of Leonard Cohen. That was pretty inspiring. It turned my head around. He showed me that poetry and music had a bed in which they could both sleep, and make love, and explore the world without ever leaving the room.

But eventually I heard Terry Riley’s ‘In C’, and Fripp & Eno’s ‘No Pussyfooting’, and I think that’s the one or two that led me to where I am now. Gavin Bryars’ ‘The Sinking of the Titanic’ was a watershed moment, for sure. I often feel like I’m just trying to get close to that sacred place when I’m working nowadays. He holds the high water mark with that composition. And I heard it thanks to Eno, on whose Obscure label it was initially released. So I guess all doors and all roads and all oceans lead to Eno.

We live in a time where noise is inescapable, engineered, curated, endless, yet your work often gestures toward silence as something essential, even revelatory. How do you cultivate quiet within your creative process, and what does that silence allow, or demand, from you as an artist? Is it a space of refuge, of clarity, or something more unknowable?

It is all of those things, really. I am exploring infinity, in a way, and that is a place that is composed mostly of silences, I believe. Terry Riley loves reverb. So do I, obviously. It bends both time and space and creates a looking-glass portal into what can never be articulated through any other medium than Sound. And by Sound, I mean Music. Music is the juxtaposition of Sounds, and Cinema is the juxtaposition of Sound and Imagery. These human spaces can provide refuge or clarity, but they can also antagonize and bring the Listener to a place that isn’t really comforting.

I prefer to offer environments of great comfort, where Love can happen, but sometimes, in my live Ambient-Cinema performances, I find myself creating soundscapes that are more provocative than inviting or sensual. I go where the moment takes me. Improvisation is the Mother of Creation. Ideally, I always endeavor to create something that takes us to a place we’ve never been before, but I also endeavor to remove my ego from the process, which can result in the music going wherever it wants to go, to what destination (or crossroads) it is drawn to. Sometimes I choose which fork in the road I want to explore. But I’ve come to feel that the results are far more often better when I allow it to choose me.

Deep Listening has a thousand faces. Read Pauline Oliveros. I listen to compositions by Terry Riley and they never sound the same twice. I can say the same for ‘The Sinking of the Titanic’. Is it the music that magically transforms itself and appears to be different, or is it something that happens inside of us when we listen to works composed by a genius? Is it an external phenomenon, or is it wholly subjective? Perhaps a bit of both.

I cultivate quiet, and SILENCE, by letting the music tell me where it wants to go. By letting go. By setting things in motion and inviting real Freedom into the process. This is nothing new. John Cage pioneered Indeterminacy long ago, and people like Tony Conrad put flesh on those bones. I’m not trying to be like them, or like anyone, but if I have heroes, Pauline and Tony and Cage (and Eno) are certainly among them. A devotional reverence for SILENCE is what they all share in common. It is where everything begins and ends.

John Cage said that the most important thing about a sound is how it begins and how it ends. I think about that credo a lot. For decades, I have pondered that dictum, and it never fails to inspire me to do more by doing less.

Over the years, you’ve embraced tape machines, analog consoles, digital tools, and yet the gear never feels separate from the emotion in your music. It’s as though your machines are not just instruments but voices in conversation with your own. Do you see technology as a kind of collaborator, an active participant in the process? And has that relationship shifted now that digital tools are both ubiquitous and often impersonal?

The recording studio is a musical instrument. I play it as such. It’s not a tool to be used. It’s a partner to be respected, nurtured, and Loved.

I touch the mixing console as I would touch a lover. Come with me on this journey. Let’s see what happens to us as a result of this time we are spending together. Let’s see if we can make something Beautiful. Because BEAUTY is the only valid form of protest in the world we are living in today. There’s little else we can do other than remind the Listener that Beauty still exists. I have no use for loud drummers, grating synthesizers, ear-piercing events, or music that draws me into the abyss and drowns me.

Maybe it’s because I am getting old now. I want Peace, and I want to offer Peace to the Listener. I want to remind myself that Peace is still possible. I want Infinity to enter the listening environment when I perform, not Chaos. There’s enough of that going around today, I think. That doesn’t mean that contrast and conflict are excluded from my process. It simply means that I take greater care now than ever before in presenting it in a manner that is optimistic and clarifying. Beauty comes in many forms, and not all of them are beautiful on the surface. Sometimes the Listener must dig down deep to hear the intentions beneath the instrumentation and execution of what I’m currently compelled to create.

“If I can conjure an experience in the Viewer or Listener that they have never imagined before, I succeed.”

There’s a tension that runs through your work, something emotionally raw, yet also carefully composed. It feels intimate without being unfiltered, intentional without losing its soul. How do you navigate that boundary between what is real and what has been shaped? Do you believe that music, even in its most constructed form, can still carry an honest emotional truth?

YES, in both songwriting (with lyrics and voice), and with instrumental music, though I’m unsure if I will ever make another record of ‘songs’. I’ve found myself in a place now wherein I’ve crossed the boundaries of words and text and settled into expressing myself solely with sound. The Art of Sound. Painting with Sound. Sculpting with Sound, and with Imagery. That is the current that fuels my Ambient-Cinema works. I’ve traded text and words for visual imagery, thus blurring the lines between what is real and what is imagined.

If I can conjure an experience in the Viewer or Listener that they have never imagined before, I succeed. David Lynch seemed to always succeed in these creative endeavors. I will fail half the time. But as a producer, I think I’ve buried my failure with a fair degree of consistency. I think what I’ve done in the last five years, in particular, has been wholly honest. I do shape what I create, but I never labour over things for long, and that keeps it honest and close to the initial idea’s place of birth, so to speak. If I don’t wander too far from the point of inspiration (the audio idea’s place of origin), the music stays real, and I can feel that it’s honest.

Some composers work for years on a piece and somehow, it still remains honest. Leonard Cohen would spend months working on a single line of poetry, and it just keeps getting more and more honest. So honesty comes in different colors for different artists. How it is achieved is secondary. I would never want the Listener wondering how I did something. I want the Listener wondering why. Even better, ideally, I wish they could forget both questions and allow themselves to become an equal part of the experience of Listening itself. Pauline Oliveros. Read her works. Listen to her music.

Much of your music seems unmoored from linear time, as though it belongs to dreams, or to memories not fully lived. Do you think of music as a way of bending time, of distorting memory? Or is it more about creating a place where memory and imagination meet and become indistinguishable?

Yes, listening to music can displace our senses in a way that suggests that time isn’t what it seems to be. And certain elements, when added, can expand and amplify that experience to an almost mind-expanding degree. La Monte Young, for example, makes music that removes me from humanity entirely. It takes me off the planet. Terry Riley can achieve similar phenomena.

I love reverb because it takes us out of the space we’re in and places us into another, when used with great care and diligence to its surrounding sounds. I didn’t add reverb to Galaxie 500 or Low records simply because it sounded good. I used it (when it was the right thing to do) to take the listener off the planet and into the unknown. Into infinity, where time and space play chess with each other and it always ends in a draw.

Memory creeps into the listening experience, and of course that means it’s a wholly different experience for each listener, since everyone possesses memories unique unto themselves. Yet somehow, when it really works, these listeners are bonded in a way that is unique to those bands.

The love people share for Galaxie 500 and the early Low records that I produced is almost religious in fervor, 35+ years after we created them together. They spark the imagination anew with each successive listen. So there must be something eternal and mysterious at work there. Something that never dies.

When used sensitively, reverb can be transformative. And don’t confuse reverb with echo. They are two different things entirely. Echo is repetition. Reverb stretches and pulls. It makes the experience itself elastic in nature and brings us to a place where we can see and hear for miles in every direction.

It brings music into the orbit of the spheres and takes us into infinity. That can be a very powerful experience, not unlike a drug. But it is clean, and honest, and it summons memory up from the depths of our minds and into the present.

It cannot be explained or described. Or perhaps I should say, I cannot adequately explain it or describe it. But I know it’s good, if I’m heading there with my heart in the driver’s seat.

You’ve often spoken about your belief that discipline matters more than inspiration, that showing up, day after day, is what gives art its shape. And yet, many of your most affecting collaborations, Daniel Johnston comes to mind, unfolded in spaces of great emotional unpredictability. How do you reconcile your methodical approach with the vulnerability and chaos that certain artists bring with them? And what kind of truth emerges from that convergence?

After spending the last few years “producing” less and composing and collaborating more, I’m not sure I still believe my previous opinions about discipline. I spend a lot of time letting go these days.

I stand in the rain without an umbrella. I don’t always eat when I’m hungry. If I feel myself falling asleep or needing a nap, I don’t go into my kitchen to brew a fresh cup of oolong tea; I go to bed. I’m not as methodical as I once was. I get more out of myself nowadays by accepting what’s coming, rather than trying to control it.

Truth comes on its own now. I haven’t had to go looking for it in a long time.

Times change. People change. The way we make art changes. Things that matter to us change. Everything changes, and change is one of the most important things in life.

I don’t think I think about stuff like this as much as you do, Klemen. It’s obvious to me that you listen very deeply, but then you’re filled with questions to which you seek answers.

What if, when we die, when all truth becomes self-evident, we find that the answers didn’t matter? And if the answers didn’t matter, then there was no point to asking the questions.

Listening is not an intellectual experience for me. It never was. I’m not an analyst. My heart is the director of this movie. I’m not trying to “say” anything in my Ambient-Cinema works. I’m trying to send the listener on a path toward discovering something new about themselves.

I don’t care why I feel the way I do when I listen to Scott LaFaro’s bass playing on Bill Evans records, or when I listen to ‘The Sinking of the Titanic.’ I’m too busy marvelling over the very fact that my feelings have been changed, and over the possibility that some of those changes might stay with me forever.

Shimmy-Disc was born out of a desire to protect and amplify music that others had overlooked, a kind of sanctuary for the unclassifiable. Now, in an age dominated by algorithmic suggestion and digital ephemera, what role does a label like Shimmy-Disc play? How do you see yourself pushing back against the machinery of modern attention, and helping unconventional voices reach the ears they were meant for?

I can’t answer questions about the “commerce” of music today. It brings my mind to a complete and utter halt. Sorry, Klemen.

You’ve spoken candidly about the unease that comes with releasing solo work, the sense that it is somehow self-serving, less about giving and more about revealing. And yet, you continue to create these quiet, atmospheric pieces that seem to say: this is who I am, even if I can’t say it aloud. What is it that solo composition unlocks for you, what kind of truth or necessity does it fulfill, that collaboration, however generous, cannot?

It’s far easier when my solo work is instrumental in nature, and not text-based. If I’m not singing about love, loss, loneliness, and the horror of being human (and I am not doing any of those things these days), I am in a very comfortable place in which creating new work is not only easy, but it’s inviting and cathartic.

Solo work is identical to collaboration in that I am sharing ideas with my various selves. I don’t see much difference between the two. I exist in every space on a 3D chessboard. I can be anywhere and everywhere at the same time.

I’m no longer excising demons. I’m summoning angels. Life is just more beautiful now, so accessing the emotions I require to create honestly, and devising a manner in which to share what I’m feeling with others, isn’t challenging at all now.

It’s like breathing the air of freedom. It comes naturally now. Like sleeping, where the subconscious says “I love you.”

There is no “necessity” in that process. No compulsion. It’s not really even something I would call “work” anymore. I’d simply call it “life.” What I do has finally become what I am, and I am very happy for having finally found my home.

Klemen Breznikar

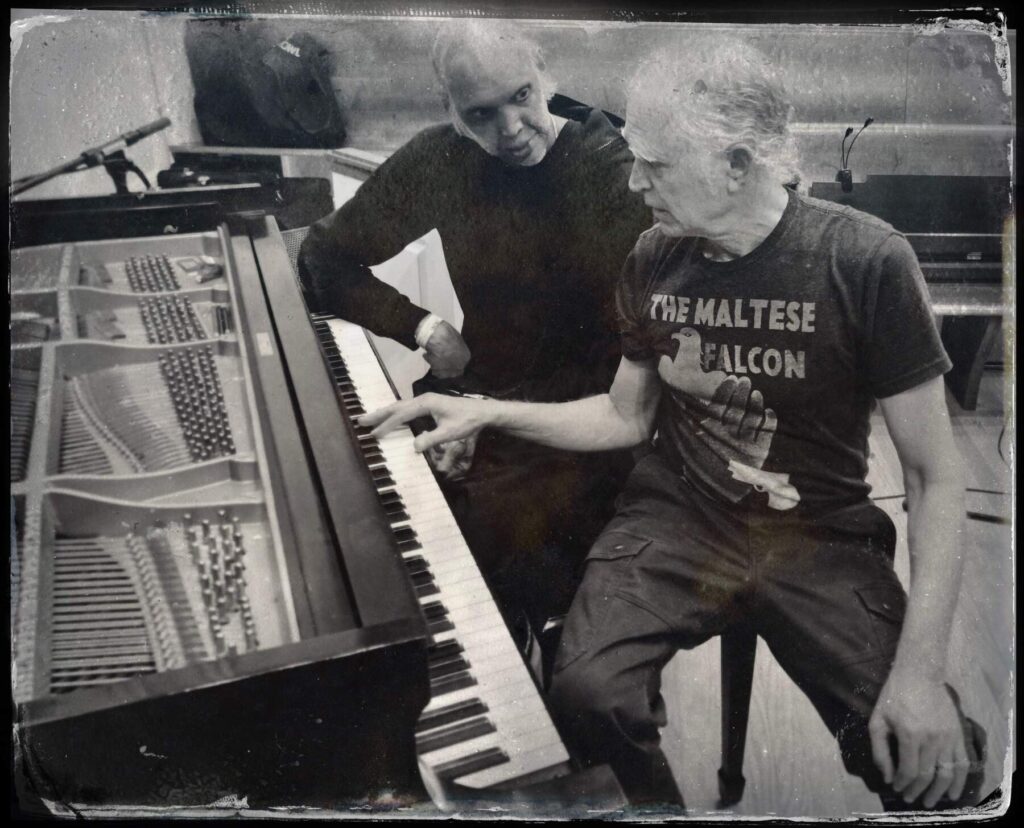

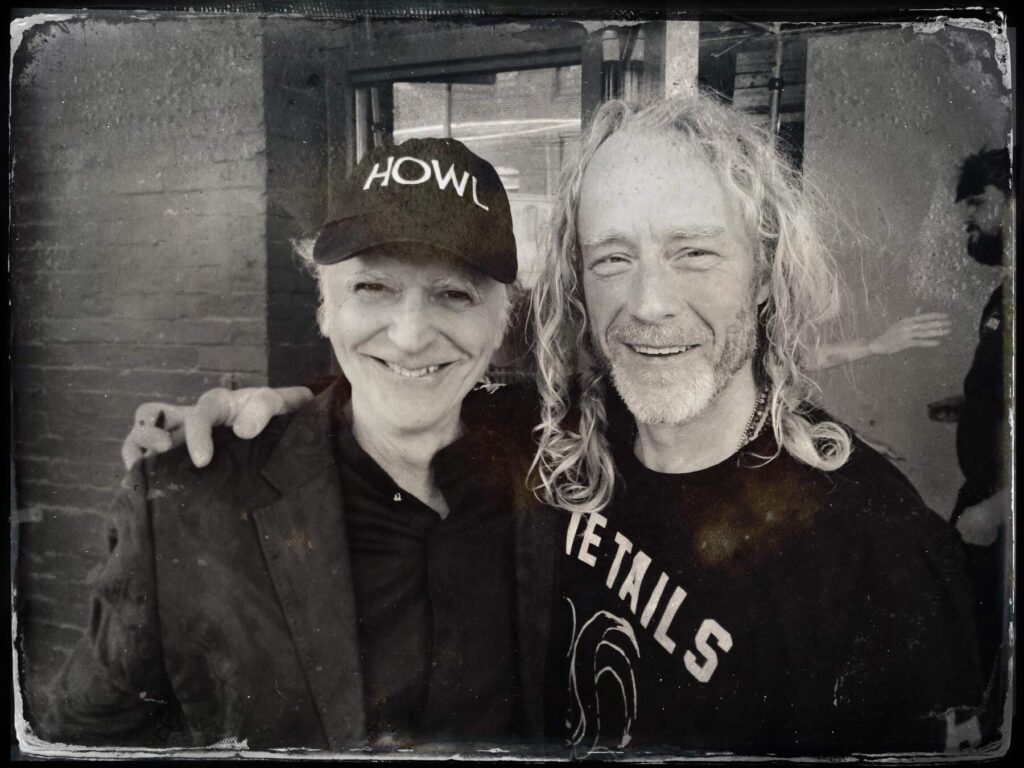

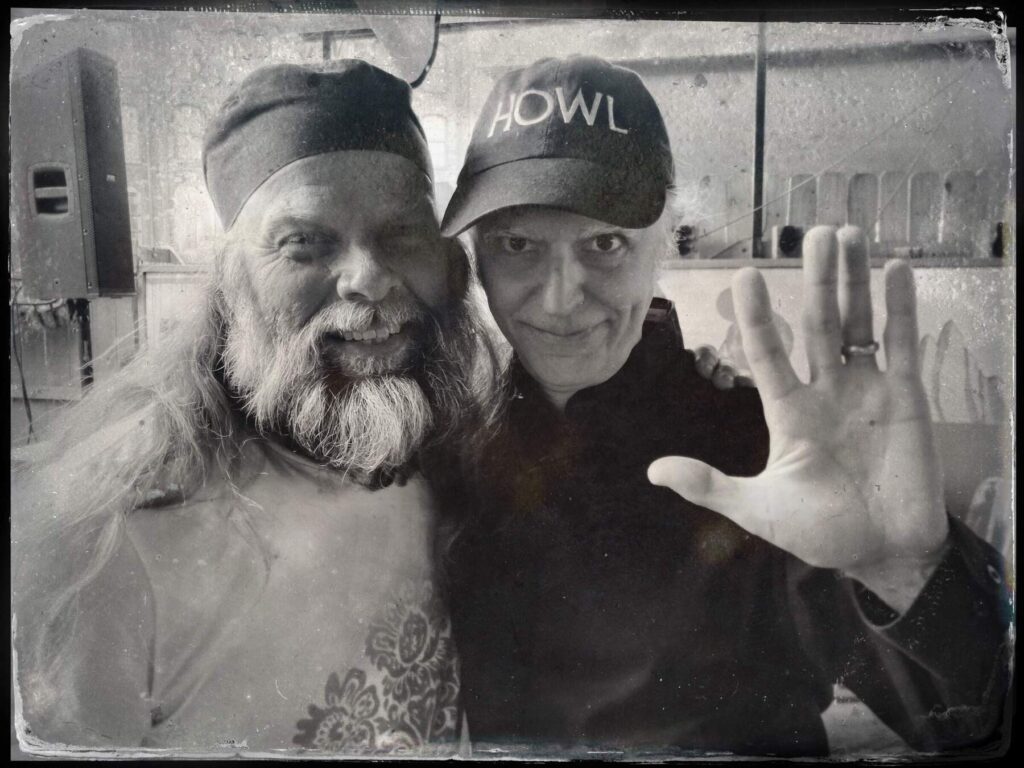

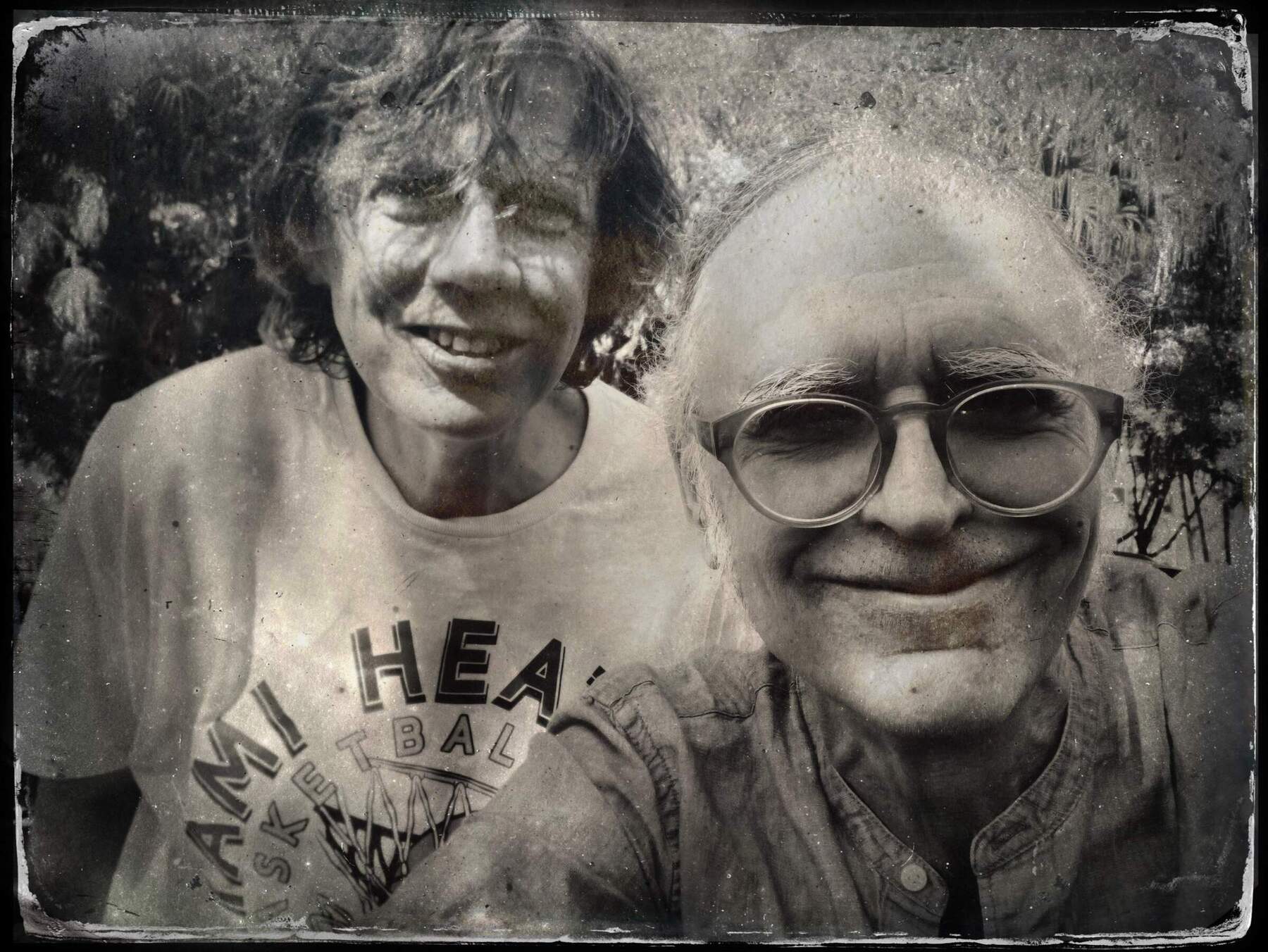

Headline photo: Thurston Moore and Kramer | Whispered collaborations are brewing in Miami, with a secret project expected to drop on Shimmy-Disc in early 2026.

Kramer Facebook

Shimmy-Disc Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp

Joyful Noise Recordings Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube

Thank you both for this wonderful interview!

Creating beauty as protest resonates deeply with me.

Witnessing Kramer creating beauty in wildly diverse ways at Big Ears was a profound experience for me. He is living it, and it is a gift to all of us.

I did a very different interview wirh Kramer with Dogbowl when they played Leeds Duchess of York in the 90s. We went to a curry house for the interview and it was like a comedy double act.

Hey Graeme, is there some place this interview is available to read? I would be interested if so.