Flute & Voice and Other Musical Passions – An Interview with Hans Brandeis

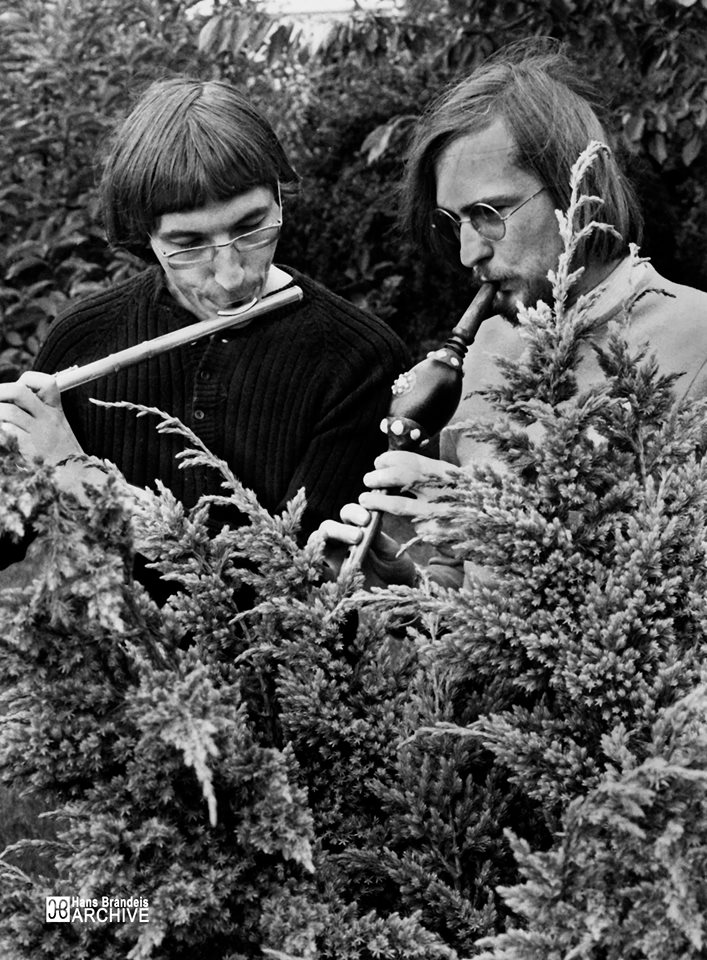

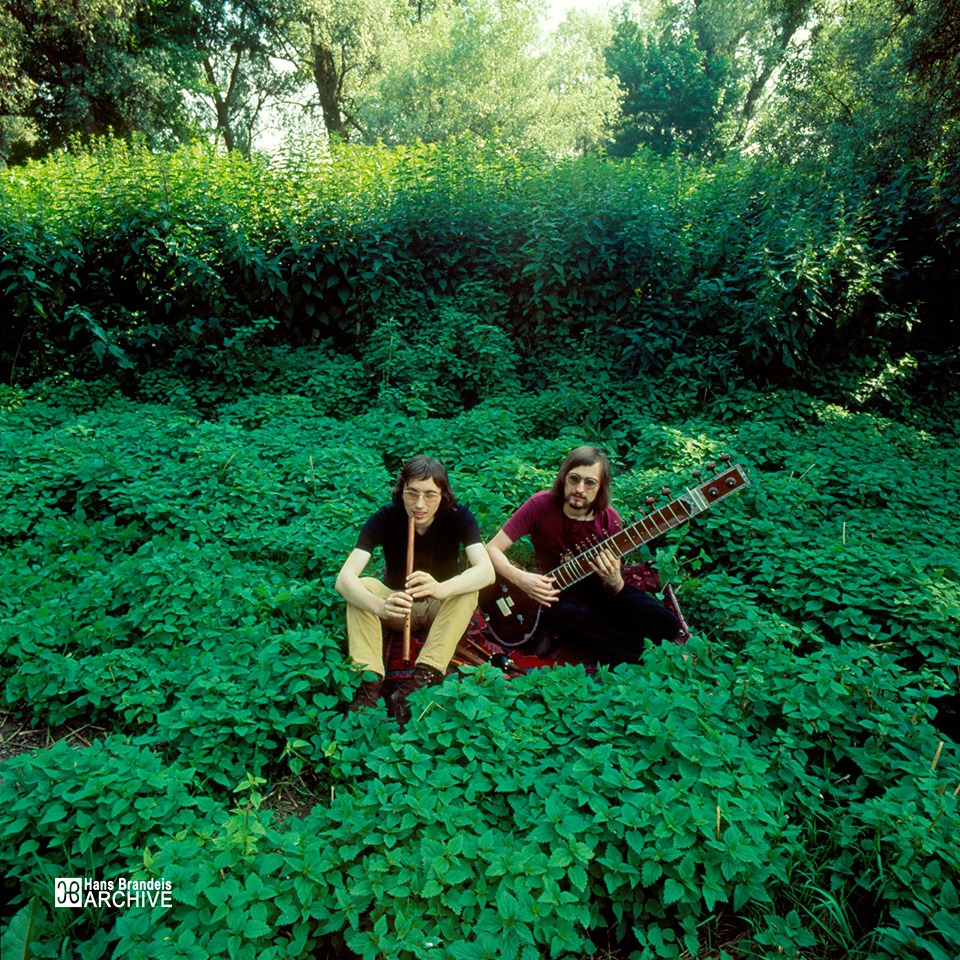

Hans Brandeis is a German ethnomusicologist, composer, singer and guitarist. He was born in Ludwigshafen on Rhine in 1949, as son of contemporary classical composer Johann Karl Brandeis. He is now living in Berlin. He is best known for his collaboration with Hans Reffert, under the name Flute & Voice. The duo released three albums pioneering in world and fusion music by blending elements of jazz, rock, blues, folk, Indian and classical European music. The first one, “Imaginations of Light” came out in 1971 on the PILZ label and has become a very expensive collector’s item. Hans Brandeis studied ethnomusicology in Berlin and, starting from the late 1970s, conducted 15 research trips to study the traditional music of the indigenous peoples of the Philippines. Because of his high interest in classical singing, Hans Brandeis, as a lyric tenor, also participated in a number of projects presenting German Lieder, arrangements of Scottish folksongs by Beethoven and Haydn, solemn arias, among others.

Where and when did you grow up? Was music a big part of your family life?

Thank you very much for giving me this opportunity, or better, for inspiring me to go back into memory lane. Of course, I can only speak for myself because you and I have missed the chance to ask the same questions to my musical partner Hans Reffert who passed away, in February 2016…

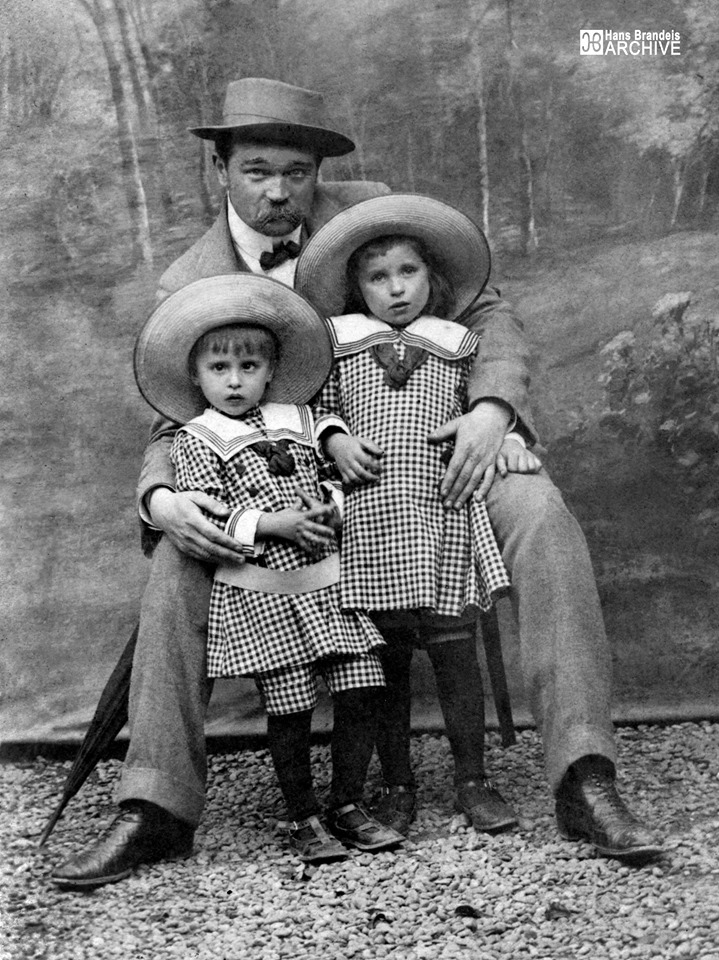

I was born and grew up in Ludwigshafen on Rhine, a city of considerable dreariness, which was recently declared the “ugliest city of Germany.” It is a city full of chemical factories, the biggest of which is the BASF, actually the largest chemical producer in the world, with a workforce of 40,000 people in Ludwigshafen alone, not counting factories in other parts of the world. My father, who had a doctorate in chemistry, used to work at the BASF, leading a small team of researchers in developing new products. However, his real passion was music, and when he was a young man, he wanted to become a composer. As a child, he learned how to play the violin and, on Sundays, together with his father who was also a violinist, he performed arias from operas and operettas that he himself had arranged for two violins. This was in a small town, on the countryside of former Sudetenland, now Czech Republic. They left the windows open so that the neighbors and people passing by on the street heard them play, and occasionally applauded…

In the mid-1930s, my father started to compose romantic songs for voice and piano, first in a style similar to popular operettas, proceeding to a romantic and late romantic style, similar to the German “Lieder.” My grandfather advised him not to study music, for reasons of simple economic survival, so that he decided to study chemistry, instead, and, at the same time, taught himself composing, as an autodidact. In that context, I should mention that he also taught himself how to play the piano when he was 17 years old, during his summer vacation break. Although, as an untrained pianist, he never reached some degree of virtuosity, his piano skills were very useful for his self studies of composition, harmony and instrumentation. Aside from more than 60 Lieder, he composed piano pieces, string quartets, a good number of works for grand orchestra, including three symphonies. In the 1960s, he had developed a style of his own, much of it very chromatic and atonal. Some of his Lieder, piano pieces and string quartets were recorded and broadcast at German regional radio stations, in Heidelberg and Stuttgart.

Yes, my family was a little bit unorthodox. My grandfather (the one with whom my father used to play the violin) was a mechanical engineer, but his passion was physics, and he wanted to disprove Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity. He always tried to write a book about it, and I still have six or seven handwritten copies of it with me. My grandmother, whom I don’t remember ever having seen smiling, worked as a piano teacher, after the war when it was hard to find a job. Later on, she wrote a book with humorous poems that was never published.

Starting from my early days as a kid, I was told that I had musical talent, and the story goes that, before I could speak, I could already hum all the children’s songs. Of course, I can’t remember anything anymore, but my sister always tells the story that I was hardly talking, and only spoke a few words in baby language, but then, within a few days, I started speaking in complete sentences. In conclusion, it seems that my way of dealing with reality and of learning how to deal with it was a little bit different from other kids’…

So, this was the musical environment in which I grew up: when I was between 9 and 12 years old, my father composed a lot in the evening, after work, and while I was trying to fall asleep in the next room, I heard him play his atonal music on the piano… Around that time, at the nearby church, I was also a member of a schola, a kind of boys’ choir, and there were some occasions, for example at Christmas time, when I was singing solo at the church, backed by the choir, pipe organ and other musical instruments. For me, at the age of 10, those were big events…

When did you begin playing music? What was your first instrument?

When I was around 12 years old, around 1961, there was this teenage boy in our neighborhood who was playing guitar, simple songs like “Hang down your head, Tom Dooley.” This was actually the first song I learned how to play on the guitar, because it only required knowing two chords. I loved listening to that young rascal, and I wanted to have my own guitar, which my parents later gave me as a birthday gift. I wanted to take guitar lessons. So, my mother brought me to a music school. However, they only offered classical guitar there, which I absolutely didn’t like… As a consequence, I just left it at that, and I didn’t touch my guitar anymore, during the following year. In any case, if you ask me what was my first instrument, in looking back, I would always say that it was my voice.

Who were your major influences?

Actually, at first, I was not at all interested in pop music. My two elder sisters always commented that all these rock’n’roll guys looked so unorderly and filthy. We hardly ever listened to the radio, and the two girls only had a couple of sentimental records like “Moon River” or “At the End of a Rainbow.” I was absolutely not inspired… Back then, I studied at a gymnasium (a kind of high school), and, in 1965, we had a music teacher who probably considered himself very “progressive.” So, he told the students in our class that they should bring all their favorite records of pop music and then we would all listen to them and discuss them. And then came this memorable day when my classmates brought their records – myself I didn’t have any – and it was the first time that I heard The Beatles. Our music teacher certainly had in mind to make us understand how simple and primitive this kind of music was, but the result of that specific music class, on that specific day, turned out as the opposite. When I heard the Beatles’ song “A Taste of Honey,” I totally freaked out. (From my present point a view, however, I would rather say that “A Taste of Honey” is such a sugarcoated song that I can hardly bear it anymore…)

Anyway, because of his composing activities, my father owned one of the first reel tape recorders that Grundig built for the consumer market. And immediately after I came home, on that special day of my “pop music coming out,” I switched on radio and tape recorder waiting for the first Beatles song that I could record. And I succeeded, or at least I thought I did, because the first song that I recorded was in fact “Needles and Pins” by The Searchers…

Did the local music scene influence you or inspire you to play music? Were you in any bands prior to the formation of Flute & Voice?

In the mid-1960s, in Ludwigshafen on Rhine, there was nothing you could call a “local music scene”… at least, I was completely unaware of it… There were a couple of youngsters who played in bands, mainly inspired by the Mersey Beat music coming over from Great Britain, including The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Kinks, The Who, The Searchers, The Hollies, The Pretty Things, The Fortunes, also American bands like The Byrds, etc. That’s the kind of music I listened to at that time. And after I became interested in Mersey Beat, I wanted to have my own electric guitar as soon as possible. There was only one local music shop in Ludwigshafen, and it was clear that I could only afford one of the cheaper instruments. Therefore, I was going for an affordable “Framus 5/168-54gl Golden Strato de Luxe.” This was a pretty glamorous guitar, all parts gold plated, in the shape of a “Fender Stratocaster.” My parents were not willing to just buy the guitar for me, but agreed to pay half of it if I succeeded to pay the other half. This, of course, was meant as a test if I was really serious about the whole music thing… So, during my spring vacation break of 1965 , I worked as a gardener at the agricultural experimental station of the BASF. I earned the needed money, got the rest from my parents, bought the guitar… and immediately started a band, together with some of my classmates. We called the band The Sharks and played songs like “Under the Boardwalk” and “Money” by The Rolling Stones. We had our rehearsals on Sundays, in a room in the basement of a church. It was the typical lineup of solo and rhythm guitar, bass and drums. All the instruments as well as the microphone went all into one single Fender Tremolux amplifier that belonged to me. I was condemned to play rhythm guitar, and the band was really bad… It fell apart when the singer/bass player transferred to another school. Only a short time later, he “accidentally” committed suicide, at the age of 18, when he was left by his 14-year-old girlfriend and tried to blackmail her into returning to him by swallowing sleeping pills, while drinking a lot of alcohol, completely unaware of the deadly effect of this combination.

I started playing with another group, and I don’t even remember their name anymore. Those were still the times of Mersey Beat, and we played with two guitars, bass guitar, drums and, occasionally with a classical flute player as well as a student of opera singing. We did that for a while but never had any performances in public. In the meantime, I had switched to a semi-acoustic Hoyer guitar in Gibson ES-335 style.

As a side note: I bought my Hoyer guitar in the same music shop where I had acquired my first one. I often went to that shop, after school, and I befriended the owners. Later on, I even gave private Latin language lessons to their son. Anyway, someday, when I was there, Bill Lawrence, at that time still known under the name Billy Lorento, came in to the shop. He had been a friend of the shop owner, Mr. Pallasch, for many years. At that time, he was touring the music shops of Germany to introduce his newly designed guitar pickup that was used on all Hoyer guitars, back then. When I met him in the shop, he played the high-end model of Hoyer, a semi-acoustic guitar with ebony fingerboard and bindings all made from mother-of-pearl. Bill Lawrence played beautifully, and the guitar just sounded awesome. I just had to have that thing…

In 1968, I finished my studies at the gymnasium and moved to the city of Mainz to study biology. Of course, I brought my Hoyer guitar with me, as well as another semiacoustic, a Gibson ES-330 that I had bought used, in the meantime. Mainz turned out to be a very boring place, rather small and without a big music scene. I had some jam sessions with local musicians. I also saw the thoroughly stoned band Xhol Caravan (interview here) performing live there that gave me a first idea of how Frank Zappa music sounded like, because they played in a similar style… However, I didn’t like the biology course, because dissecting animals was really not my thing… My Mainz experience lasted for a year, but was soon forgotten.

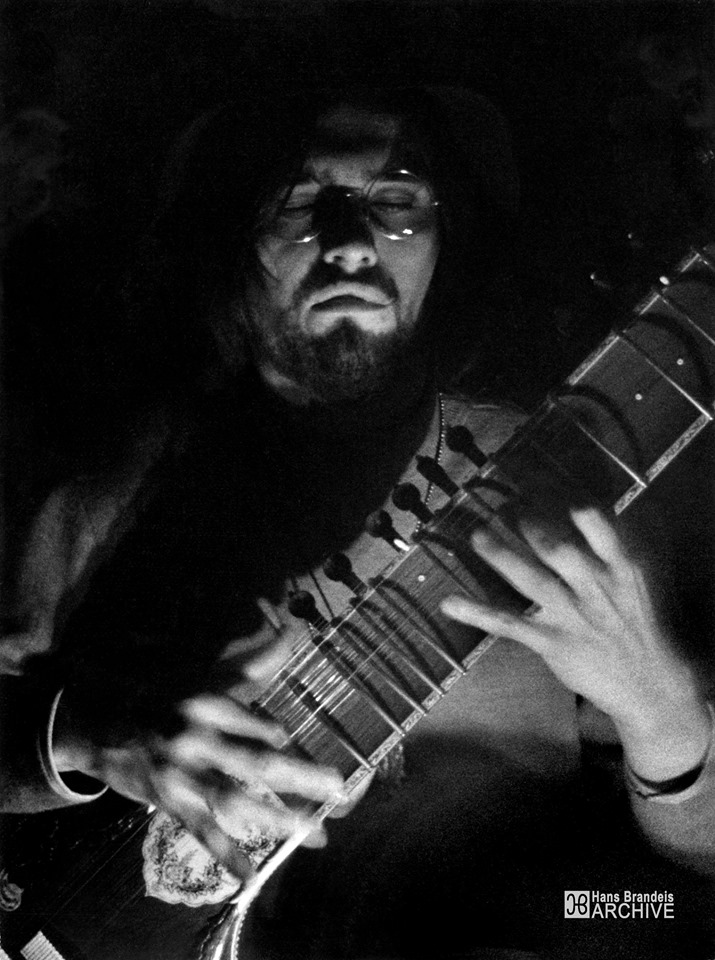

My musical taste had considerably changed, in the meantime. I now loved the guitar styles of Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix. I became very interested in the music of Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention and other stuff that was unusual at the time. And I developed an interest for Indian music. Since I had heard the Indian sitar for the first time on the albums of The Beatles, it had always been in the back of my mind. In Mainz, I discovered and bought my first album of Ravi Shankar, “Live at Monterey Pop Festival,” which struck me like lightning. From that moment on, I knew that I would own a sitar someday…

1969 became a crucial year for me, with many things happening and with a whole bunch of new musical influences. I moved from Mainz back to Mannheim and enrolled in psychology at the university, leaving biology behind. I wanted to deal with human beings and their different personalities, but was disappointed again because the psychology course in Mannheim was mainly focusing on statistics and psychometric methods testing. The more I had a reason to focus on music…

“Our music was clearly influenced by Frank Zappa.”

I had always been highly fascinated by singing in general and classical singing in particular. I started listening to German Lieder performances by classical baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and tried to learn some songs of Franz Schubert. I visited the father of a schoolmate who was a director of church music and asked him for advice. After singing some of my self-taught Schubert Lieder to him, he connected me with a classical soprano, Kammersängerin Erna Seremi, who was teaching at the Conservatory of Music in Mannheim. I started taking lessons with her for about three years, although I definitely never planned to become a classical singer. I found and still find opera singers impressive, but I always have the feeling that there is too much testosterone involved, among operatic tenors. Heroic or dramatic tenors sound kind of “violent” to me. I prefer the more intimate worlds of German Lieder that present short dramas or three minute operas in themselves. I prefer subtleties in vocal expression, and I want my voice to sound intimate as well – just like it was the case when I was singing with Flute & Voice. But it was just a fact that my natural way of singing was very close to classical technique. Also, I always wanted my voice to sound strong and clear, although I also loved to listen to the rough and hoarse voices of blues and soul singers. But my voice was just made for something else…

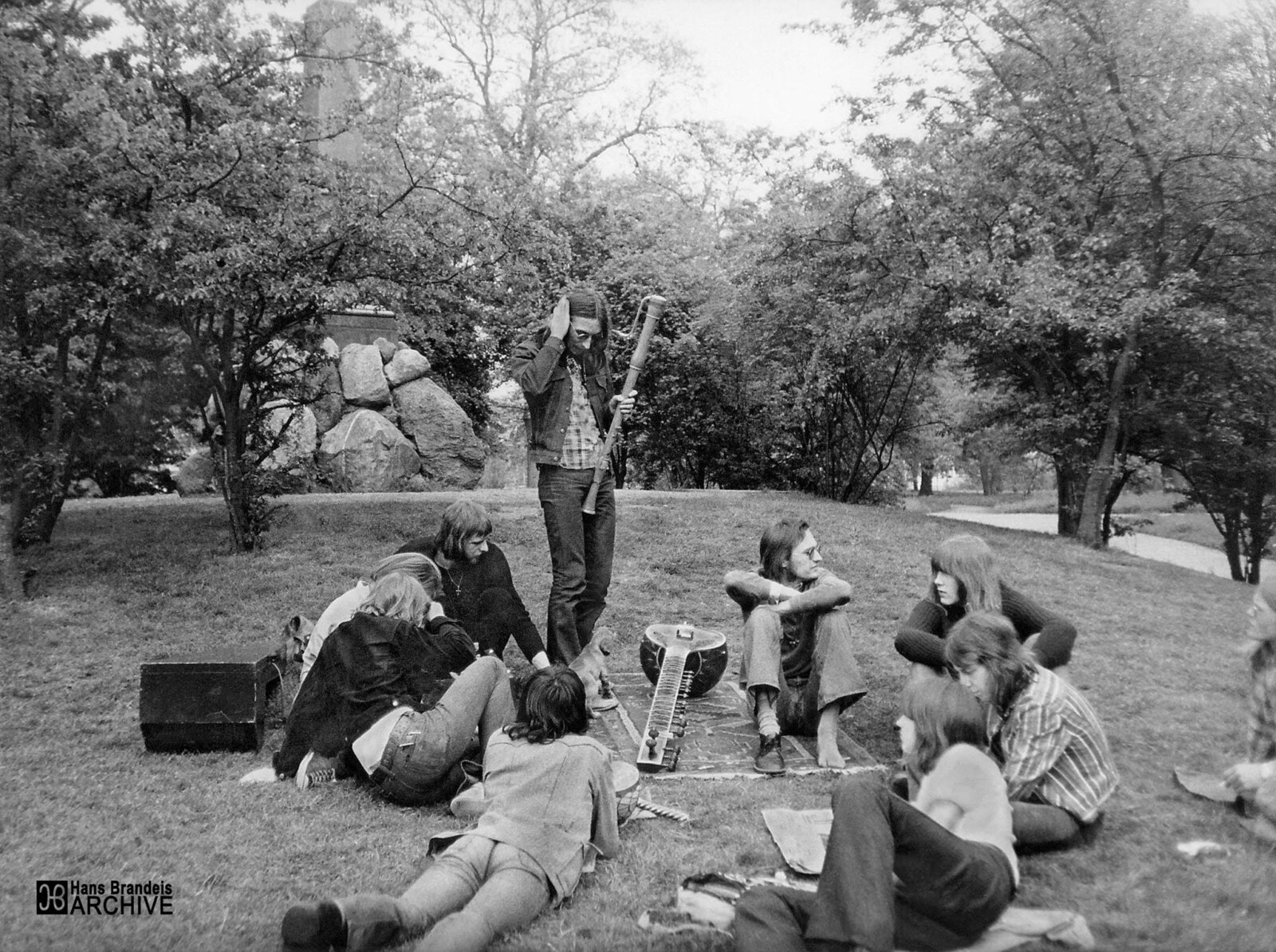

In the summer of 1969, I joined a group of young students who were still going to school, while I was already at the university. I felt a little bit out of place, but making music was still fun because the boys were really open to new ideas. The fun part started with the name of the band, ClâocoçülcEP that was a combination of all kinds of acronyms. We only had one public performance at a local festival called “Pop 69,” on October 26, 1969, in the town of Weinheim. Our music was clearly influenced by Frank Zappa, as I inserted little speeches, in between songs like “Serenade for a Cuckoo” of Jethro Tull (original by Roland Kirk) or “Summertime,” and I played sitar and sang parodies of Schubert’s classical Lieder. The audience was very surprised to see this so that they even stopped dancing and simply watched us in awe… The guitar player of that band was Claus Deubel, and, as you can see, many of his photographs are present here, in this interview. He also moved to Berlin and, after all these years, we still meet regularly and play tennis, once in a while…

Can you elaborate on the formation of Flute & Voice?

As is always the case, things do not just happen out of nowhere. A couple of other things had to happen first, providing the prerequisites, until the time was ripe for Flute & Voice.

In 1969, I came to know Pepito Bosch, a Filipino friend and a cultural icon in the Philippines who, at that time, studied philosophy at the University of Heidelberg. Later that same year, Pepito would marry my sister, and she would go with him to Manila where she would live for 15 years. Pepito was the perfect networker, especially in art circles, and he had lots of friends everywhere, simply knew everybody. I asked him if he knew any students from India who might be able to procure a sitar for me. And so it happened, I met an Indian student, and I bought a sitar from him…

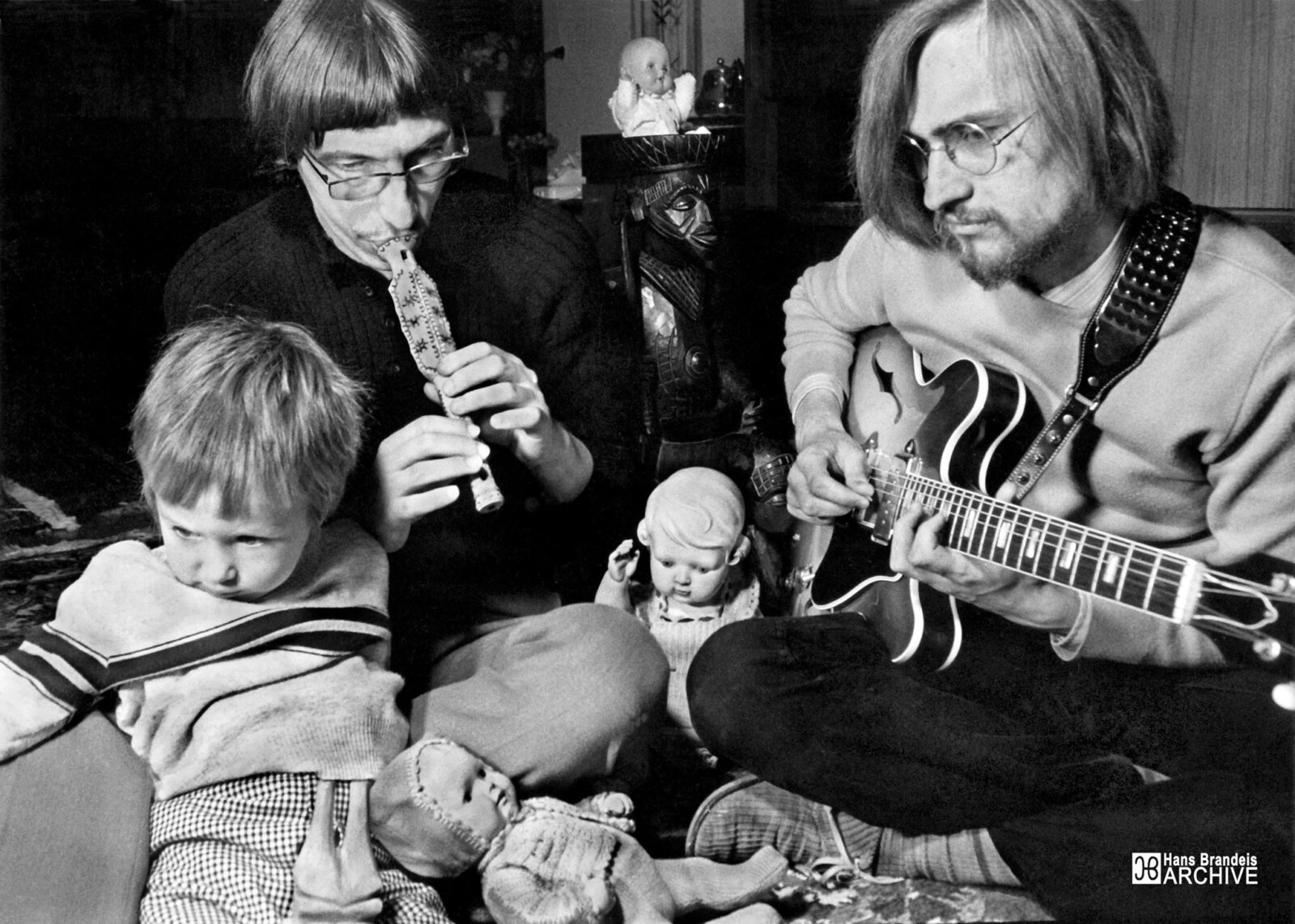

Now, this is the point where Hans Reffert comes into the picture. When I met him, Hans was already very well known among musicians in the Mannheim/Ludwigshafen area, for his unique guitar style. He was also born in Ludwigshafen on Rhine and started out as a professional musician at a very early age. He was a member of The Adventures, a professional soul band that used to play in all the popular clubs frequented by American soldiers stationed in the Rhine-Main area. They made an all-black music for a mainly American audience playing the soul repertoire, up and down, from Wilson Pickett, Sam & Dave and Otis Redding to James Brown… and they were really good at it! It was a tough music scene, and I still remember that the bass player made music just for fun, because his main job was actually being a pimp. I saw The Adventures play several times in one of those nightclubs in Mannheim, but I never talked to Hans Reffert at that time. Aside from playing with the band, Hans also studied classical traverse flute at the Conservatory in Mann-heim; he worked as a guitar teacher at a private music school run by Werner Pöhlert, who had been voted as the #1 jazz guitarist of Germany, in the 1950s, and he also worked in a local music store in Ludwigshafen. In his free time, Hans was also a passionate visual artist.

So, after I had bought that first sitar in Heidelberg and started fiddling around on it, I noticed that the resonating chamber made from a calabash was broken and that it had been very badly repaired. I also knew that Hans Reffert had a sitar at home, although I never saw him play on it. So, I brought my newly bought sitar to the music shop where he was working and asked him for advice. Basically, he didn’t know much about sitars, but it was pretty clear that this instrument had to be returned to the seller. And this is what I did. I returned the sitar and, after a while, received another one from the same seller, which is the one that I used for all my recordings with Flute & Voice and which I still have at home…

This was the first time I talked to Hans Reffert, and I also told him that I would like to join a band. Of course, I didn’t expect anything to happen, in this respect, just out of nowhere, but I knew that I would have to make things happen through taking action. So, one sunny day, I went to the house of Hans Reffert’s parents where he was living at the time, and rang the bell. Hans was probably a little bit surprised to see me. And when we were upstairs in his room, I started talking again about my dream to join a band. He obviously didn’t know what to say and stuttered things like, it’s not easy, problems, problems, making music is a difficult affair, blah… So, I said: “Well, you know, I will just give you an idea what I can do!” And I grabbed an acoustic guitar that was hanging on the wall of his room and started playing and singing a song. Hans was very surprised and, later on, he repeatedly said that something like this never had happened to him and that he had never expected me doing that…

Maybe one month after that visit, I received a telephone call from Hans telling me that he had been impressed by my performance and that he was planning to set up a new band. I was supposed to be the singer, Hans Reffert would play the guitar as well as his silver traverse flute, thus adding another wind instrument to the baritone sax of Thomas Böhmer; Martin Lill who had studied Renaissance lute in Basel, Switzerland, should play the guitar. There was a jazz drummer who was thinking of moving from Berlin to Mannheim, and a double bass player who I don’t remember anymore… We just had a few rehearsals, I still remember practicing “In a Shanghai Noodle Factory” by Traffic, but the group didn’t work out. There was just too little inspiration and joy of music making. I think the breakup had also something to do with the fact that Martin Lill went to the USA where he joined the Children of God. During this religious “experience,” Martin turned schizophrenic and, after spending some time in a mental hospital in the USA, returned to Germany where he committed suicide.

“We tried to combine all the influences that each of us was able to contribute.”

After this nameless band with Hans Reffert had disbanded, I didn’t hear any¬thing from Hans for a while. Then, one day, he called me on the phone and told me that he would like to start rehearsing with me alone, and if it would work out, we should just go on as a duo. And, yes, we already had a date for our first gig, about three weeks later. I was shocked, amazed, flattered, surprised… because it was Hans Reffert, the #1 guitar player in the Ludwigshafen/Mannheim area who made that proposal…

So, we met at the house of Hans Reffert’s parents for our first rehearsals, during the weekend of May 2-3, 1970 as well as the following weekends of the month of May, including the holidays of Pentecost. Already during the first two days, we developed the basics of our repertoire and outlined the pieces that we would record for our first album, “Imaginations of Light” later that year, although in the beginning, the pieces still had strange titles like “Questions and Yes” (later “Thoughts”) or “Imaginations of Light and Longing For”… We tried to combine all the influences that each of us was able to contribute: myself playing guitar and sitar and singing in my somehow classical style, Hans Reffert playing guitar, bass recorder, traverse flute and a bunch of other flutes and whistles. We immediately felt at home with each other because our introvert personalities worked on the same wavelength… It just clicked, and it was easy to play together, because the chemistry was just perfect…

We had our first public concert on May 25, 1970 in Frankenthal, a town near Ludwigshafen on Rhine, in a small discothèque called POP SHOP, the second performance on June 11, 1970 at the Technical College of Furtwangen, some hours away from Mannheim. At that time, we still used the name “The Flute and the Voice.”

This first public performance was truly laden with deep emotions of excitement, fear and joy. POP SHOP was just a small place without a stage so that we had to set up our equipment on the dance floor. Before starting the concert, we were outside of the disco. Maybe, we ate something, somewhere, I don’t remember anymore. So, when we entered the club again, the audience was all in darkness, with some spotlights shining brightly right into our faces. I had no idea what was beyond that wall of light and darkness. I had totally gone into tunnel vision so I didn’t perceive what was going on, left or right, or farther away than two meters in front of me. We went through our set, and while I was playing the sitar, I felt that tears were running down my face. This shocked me even more. And it was only after the concert, when the lights went on, that I realized that the audience had only consisted of five people… But, still, I will never forget this very special occasion…

In July 1970, as a singer and guitarist, I temporarily joined another band, Nightsun Mournin’ that was greatly inspired by the sound of Blood, Sweat and Tears, with a horn section and Hammond organ. There were hardly any performances, aside from an appearance at the so called “Mittwochsparty,” a radio show for teenagers, with changing live bands. However, Nightsun Mournin’ split after a relatively short time. One half formed a hard rock quartet named Nightsun, while the other half developed into King Ping Meh. Myself, I went my own way and exclusively focused on Flute & Voice, from that time on…

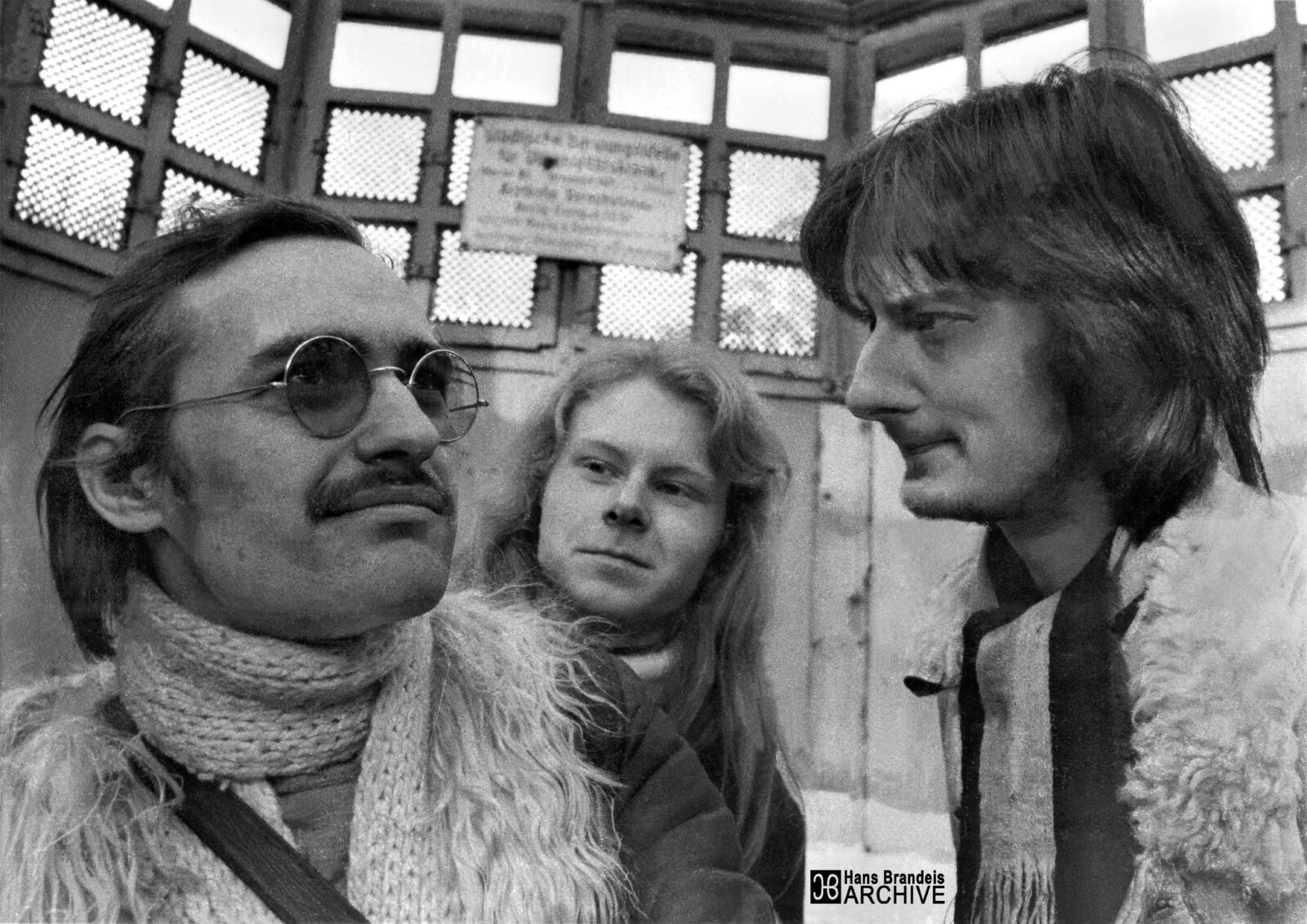

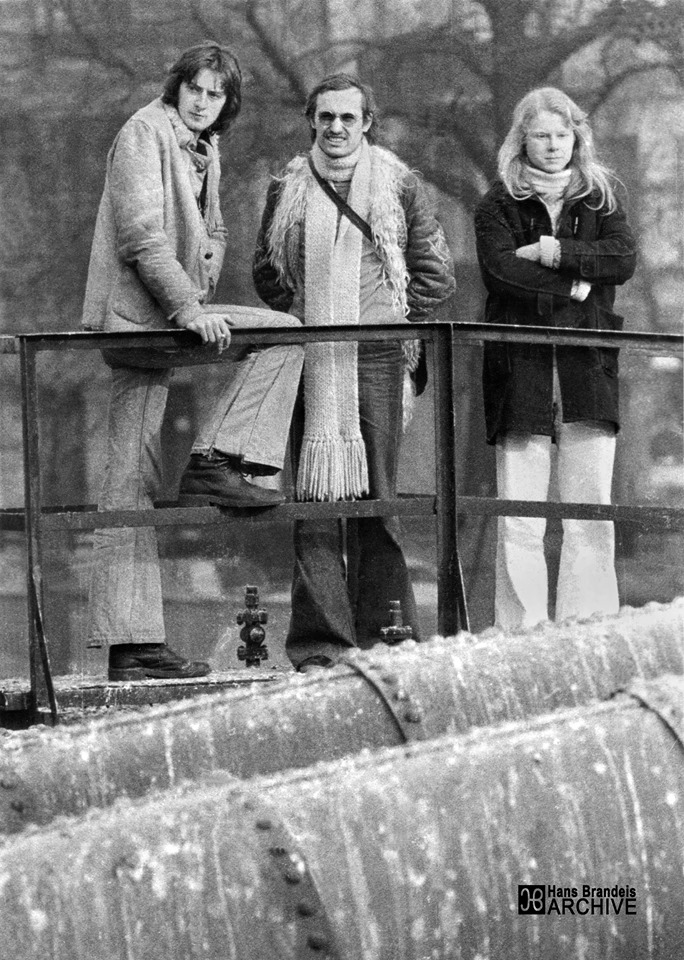

At that time, I had moved into a house called “Bayrisch Zell“ that used to be a small hotel but was now almost a ruin. A good number of musicians lived there, including some members of the progressive band Nine Days Wonder. This place was also the main hub for drug trade in southwestern Germany. I didn’t even know that when I was staying there. Of course, during these days, simply everybody was somehow fiddling around with drugs so that I just took it for granted that the same thing was happening at “Bayrisch Zell“… But I was never really interested in drugs so that I just didn’t care… It was also in the backyard of “Bayrisch Zell“ and in the neighboring house that was a real ruin where many of the early photographs of Flute & Voice were taken…

How did you decide to use the name ‘Flute & Voice’?

Well, I guess it would have sounded pretty silly if we would have called our duo Hans & Hans… or Reffert & Brandeis, Brandeis & Reffert… What’s the use of using two names that nobody ever heard of? Instead, we wanted the band name to be more programmatic, telling something about the character of the music. It was a fact that our main instruments were guitars… So, how about Guitar & Guitar? No way… Instead, we decided to stress our differences. Hans was studying classical flute, and myself, I was taking voice lessons. And Flute & Voice sounds better than Voice & Flute… The first version of the name, The Flute and the Voice sounded too bulky so that we shortened it… That’s all…

What influenced the band’s sound?

There was absolutely no example or model that we could follow, at that time. At least, we didn’t know any. We just looked at the instruments that we could play and at our individual talents that had been shaped by different styles of music. Hans was more into rhythm and blues, loved Chuck Berry, had played soul music in American clubs, had some background in classical flute playing, while myself, I was more on the rock and blues side, loved Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix as well as the sitar playing of Ravi Shankar, although I never wanted to go into classical Indian music, I had a partly trained classical tenor voice, and there was always the atonal music of my father, in the back of my mind. So, Hans and myself, we just tried to combine what we had, in a very pragmatic way, not following any particular style. Our talents were complementary so that each of us covered very different musical styles that we just tried to match together. We were also aware of the fact that listening to two guitar players might sound pretty samey for the audience, after a while, so that we tried to enrich our music with as much variety and diversity as possible, by changing the combination of musical instruments and performance styles from piece to piece.

It was only later, when we had already worked out our typical Flute & Voice repertoire that we realized that our music showed similarities with some other musical acts, like Incredible String Band or Oregon Ensemble, but their music had no impact on ours.

How did you get signed to Pilz Records?

After we started our Flute & Voice project, it didn’t take long until we were successful in getting a record deal. There was this band called Joy and the Hit Kids that was later renamed to Joy Unlimited, all studied musicians around singer Joy Fleming who later also performed at the Eurovision Song Contest. Of course, Hans Reffert knew them quite well because they were also very active in the American music club scene. One of the guitar players was Klaus Nagel. He had studied Baroque lute at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis in Basel, Switzerland, for five years, but still remained connected to the Hit Kids. After returning to Mannheim, he joined a publishing house and recording company running under two names, Badenia-Musikverlag Willi Sommer and Vineta-Musikverlag. Aside from Joy Unlimited, he produced the commercially very successful group The Flippers, in those days. (If you are looking for instant diarrhea, you should listen to their music.)

Hans Reffert contacted Klaus Nagel who told him that the BASF factory, located in Ludwigshafen on Rhine, was about to start its own record label called PILZ where we might have a chance to get a deal. Klaus Nagel himself was not the typical rock or jazz guy but, because of his studies of Baroque lute, had a much broader perspective and taste so that he really liked our music. For him, the commercial aspect was still important, but not overpowering everything else… Our chances would have been definitely much lower with another record producer. And the PILZ guys, on the other hand, were not really concerned about which styles of music they should feature. It seems that they just wanted to start their own record label, by all means, with whatever kind of performer or music…

How many copies of the first album were pressed?

I don’t know how many copies of the original album “Imaginations of Light” were pressed. In the 1980s, I looked through all the receipts sent to me by the GEMA (Society for Musical Performing and Mechanical Reproduction Rights) trying to compile how many copies of the album’s first 1971 release had actually been sold. Here are my findings, according to countries:

Germany: 1,692

Austria: 50

France: 288

Sweden: 63

Switzerland: 45

Japan: 681 albums + 99 singles

According to my calculation, 2,819 copies of the first vinyl edition of “Imaginations of Light” have been sold in Europe between 1971 and 1974, as well as in Japan in 1981. This might not sound very impressive. However, considering the fact that the album “Imaginations of Light” presents a rather unusual kind of “minority music” and considering the fact that those were the 1970s, these numbers were not bad at all. I find it especially interesting how many copies were sold in Japan alone. I never held a copy of the Japanese edition in hands. But I know that it was different from the German edition that was also sold in the other European countries, because all the text was printed in Japanese, and the design was modified as well. A while ago, I saw one of those Japanese copies offered on eBay for $1,000, while the German releases from 1971 are usually traded between €300-400, nowadays.

“The original recordings that basically consisted of very long spontaneous improvisations.”

What’s the story behind your debut album? Where did you record it? What kind of equipment did you use and who was the producer? How many hours did you spend in the studio?

Our recording sessions for “Imaginations of Light” were scheduled for August 1970. Our producer, Klaus Nagel from Badenia/Vineta in Mannheim always had a great preference for the Bauer Studios in Ludwigsburg, near Stuttgart. Bauer Studios, founded in 1948, is the oldest privately run recording studio of Germany. It’s obvious that a place with such a long history saw and heard the creation of many great musical works from international artists, among them John Abercrombie, Al di Meloa, Stevie Wonder, Helen Schneider, Carla Bley, Keith Jarrett, Chris Barber, Mr. Acker Bilk, Randy Brecker, Till Brönner, Madeline Bell, Cecilia Bartoli, Philipp Glass, Yehudi Menuhin, etc. (more here)

We recorded all the four tracks of our album “Imaginations of Light,” as far as I remember, in one single day. Maybe there was still another day, some two weeks later, but I’m not sure. At that time, there were no multitrack recorders available at Bauer Studios yet so we recorded straight to stereo tape. One or two takes, and that was it… I think it was only the title track that we recorded twice. And everything happened live at the studio, without any dubbings, including the vocals. The original recordings that basically consisted of very long spontaneous improvisations were just shortened a bit by cutting out parts that were too lengthy.

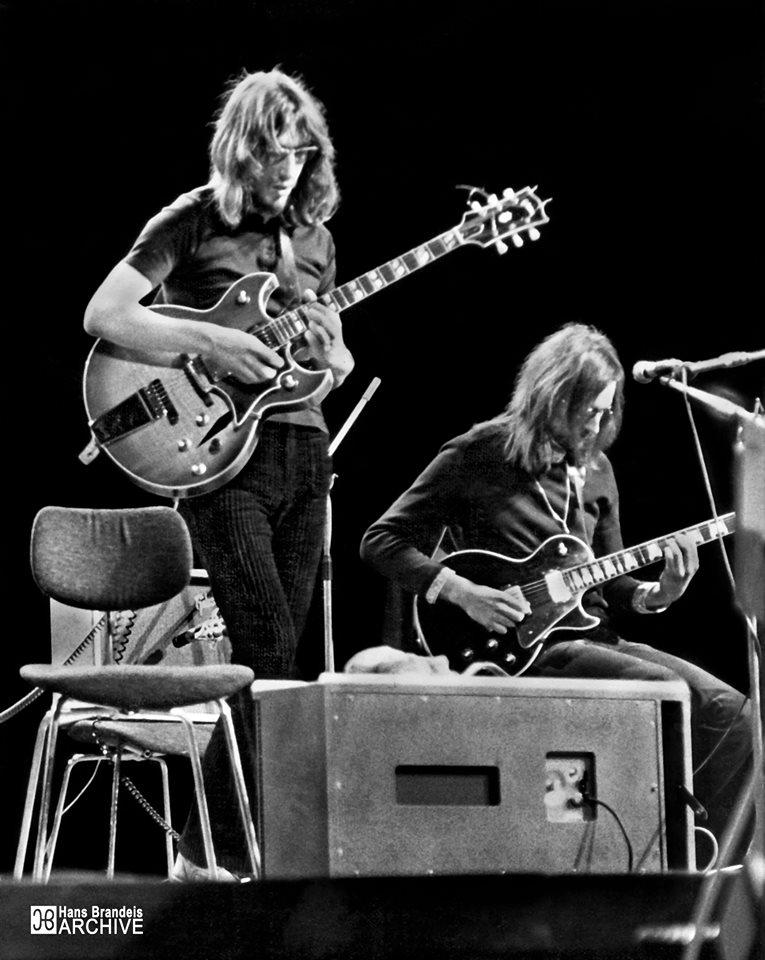

We also didn’t use any fancy equipment. I used my Indian sitar, my semi-acoustic Gibson ES-330 (for “Thoughts”), my new black Gibson Les Paul Custom (for “Resting Thinking About Time”) and my Fender Tremolux amplifier. Hans Reffert used a Gibson ES-175 from around 1960 that actually belonged to Klaus Nagel (for “Thoughts” and “Notturno”), his own Gibson SG Standard (for “Resting Thinking About Time”), a Vox AC-30, a bass recorder (for “Imaginations of Light”) and some small wooden folk flutes (for “Notturno”). There were no sound effects used. The only unusual thing was that, for “Notturno,” the sound of Hans Reffert’s Gibson ES-175 was picked up by a microphone, to give it a basically acoustic sound, while enhanced bass frequencies were added coming from the amplifier. (Or was the guitar directly fed to the mixing console, for the bass frequencies? I don’t remember.)

“…our music that was somehow meant to make the “OM” sounds of the universe audible…”

Please share your recollections of the sessions. What were the influences and inspirations for the songs recorded? Was there a certain concept behind the album?

Bauer Studios had been a movie house before so that its main recording room was huge and suited even for big bands, orchestras and choirs. We set up our stuff in this room, which was completely black, with just a little light pointing towards where we were sitting. In a way, it felt like floating in a nowhere land, in outer space… So, it was a very quiet place that perfectly fitted to our music that was somehow meant to make the “OM” sounds of the universe audible, a kind of eternally flowing and floating music. This is true for all the four pieces on the album.

Would you share your insight on the album’s tracks?

Actually, I gave rather detailed descriptions of the individual tracks on the reissues of our albums, but I will just summarize them here again…

“Imaginations of Light” kind of catches the atmosphere of Indian music, although there is nothing Indian about it, except for the melody drone principle. Still now, I find the combination of a European bass recorder with an Indian sitar pretty unusual and fascinating. What is also unusual is the combination of the sitar with a human voice singing parallel melodic lines. This does not exist anywhere in Indian music and is a style that I developed completely on my own. It’s similar to the way some guitar players are singing along with their guitars during solos. Only the main theme in the beginning and at the end of the song, as well as a melody at the end of my sitar solo were composed. Everything else in this song was improvised. Of course, we followed a general outline of the piece, starting with (1) the theme, (2) flute and sitar together, (3) bass recorder solo, (4) flute and sitar together, (5) sitar solo, (6) flute and sitar together, (7) final theme… THE END.

I would have loved to have a video of our performance of this song, but video equipment did not exist in the 1970s yet. It was only recently that I edited a video of “Imaginations of Light” by making a collage of old photographs of Flute & Voice. It can be found here:

“Thoughts” reflects a dialogue between two people. In the first part, you repeatedly hear a blues phrase representing the usual small talk, like “Hello! How are you?” etc. Starting from there, two guys start to become more and more inspired in their exchange of ideas, represented by chromatic and atonal improvisation. More and more, they develop a back to the roots attitude, like “Hey, brother, we are all…” that is represented in a blues part. In the original recording, I was singing a blues of B.B.King (“How Blue Can You Get”) but we were not really happy with it, and removed it for the album version… After the blues part, the conversation turns vague again and loses focus, in loose, free improvisation, until it finally runs out of topics, so to speak.

“Resting Thinking About Time” recounts the story of an LSD trip. I wrote the song and the lyrics and tried to create this specific atmosphere by only using my imagination, because I never took LSD in my life. The sound of the voice is intentional. I tried to sing as soft as possible so that it would almost sound like whispering. Hans Reffert and myself are taking turns playing solo and rhythm. The main guitar solo is played by Hans Reffert and, in my opinion, it is the best solo that he ever played. Heavenly! Or, that song shows heaven and hell, at the same time… Everything in this song is composed, except for the solo guitar parts.

“Notturno” means “Night Piece,” and it represents a state of sleeplessness, a living nightmare, when all the demons of traumatic experiences and memories come out of their hiding places. The dark atmosphere of this song came very easy to us, as we recorded it while being surrounded by the Nirvana-like darkness of Bauer Studios’ recording hall. Our intention was to create a contrast between strong emotions and complete emotional emptiness. Only the theme played in the beginning and at the end was composed, everything else in between was freely improvised. Of course, we followed a general outline, composed of different parts leading to a climax. This was basically my job, while Hans Reffert made his bluesy and jazzy comments on the solo guitar.

How pleased were you with the sound of the album? What, if anything, would you like to have been different from the finished product?

Basically, the sound of the album was okay. The main problem was that we did not produce high volume music so that there was a lot of hiss on the recordings. And there was no Dolby A noise reduction equipment available at Bauer Studios yet. As a result, on the final vinyl album, the high frequencies are pretty much filtered down so that the whole album became a little bit too dark and mellow. On the other hand, you could also say that this dark sound enhanced an atmosphere of mystery. On “Thoughts,” the balance of the two guitars was also a little bit, well, “unbalanced.” All this, including the hiss issue, was solved for the compact disc edition that came out in the 1990s.

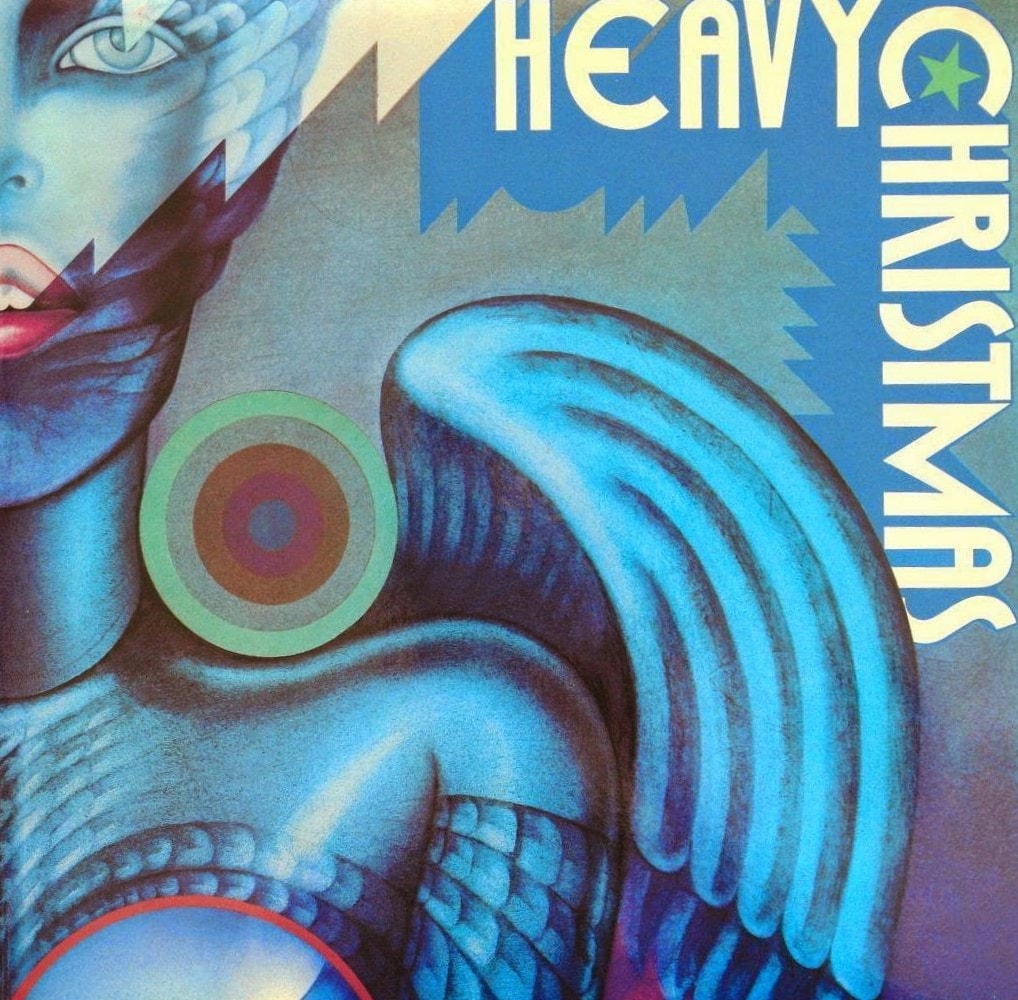

At this point, I should mention that, in 1971, shortly after the release of “Imaginations of Light,” PILZ Records released a sampler with the title “Heavy Christmas,” on which Flute & Voice were also represented with one track. This album was a compilation of traditional Christmas songs arranged in a rock style and all performed by German groups and soloists. Personally, I hardly liked any of the renditions on this album that were mostly just two gimmicky in mocking some beautiful traditional melodies. For me, up to now, Christmas is still the fest of love, despite being connected with all kinds of commercial interests.

For the Flute & Voice contribution, I selected a very rare song, actually one of the oldest religious songs in German language: “Es kommt ein Schiff geladen.” However, I somehow didn’t like the idea of singing it in German, but thought of singing it in Latin, instead. The only problem was that I didn’t find any Latin version in existence. So, I contacted my old Latin teacher from my highschool/college days, Dr. Schunck, and asked for his help in the translation of the lyrics. At this point, I should mention that, all through my school career, I had very bad grades in Latin, and this teacher had always been a source of constant fear, a real nightmare for me, for many years. Nevertheless, he was happy to see me and helped me out with the translation. The new Latin title was now “Ecce Navicula” (“Look there, the ship”).

Of course, we wanted to give the song a Flute & Voice touch. It was based on a traditional arrangement for voice and classical lute that I found at the library, and Hans Reffert actually played the original lute part on an acoustic steel string guitar, while I was singing the original melody with the newly translated Latin text. To give the song a special touch,

I played a parallel melody on the sitar. And to make the piece sound even more contemporary, we added a middle part, a cluster of drone sounds composed of different flutes and human voices that served as a background for an improvised solo on a soprano recorder played by Hans Reffert.

How about your second album? “Hallo Rabbit” was recorded soon after your debut. It wasn’t released, at the time. The recordings can be found on “Drachenlieder.”

On the carton of the master tape of “Hallo Rabbit,” there is a date written: 2. XI. 1973. However, I’m not sure if this was really the date when the final mix was done, or any later date indicating the beginning of the copyright. Anyway, “Hallo Rabbit” was not really recorded soon after “Imaginations of Light”, but actually more than three years later.

Now, for clarification: “Hallo Rabbit” was our second album, while “Drachenlieder” was the third one. On the CD reissue from the 1990s, “Imaginations of Light” and “Hallo Rabbit” were released on one single CD. Because of lack of space, the last piece of “Hallo Rabbit” called “Reprise” had to be left out. “Drachenlieder”, on the other hand, was a separate production that was released some years later.

Anyway, since the recording of “Imaginations of Light,” many things had happened. Hans Reffert had divorced from his wife in the meantime, and the two of us shared a flat together with our girlfriends and another two friends. The flat was located in a suburb of Ludwigshafen on Rhine, a former farming village, and it was actually an old drugstore, with all the old wooden shelves and the counter still installed in the former salesroom. As we were living in the same apartment, it was very easy for us to rehearse and add new songs to our repertoire.

“Our musical style had changed, evolved, developed.”

Since the release of “Imaginations of Light,” we had given a good number of concerts, we had gained confidence, and we were slowly moving away from our meditative music style. For example, when we played “Thoughts” during concerts, we didn’t have that quiet jazz guitar sound anymore that people were familiar with from our album, but we started playing the piece with distorted guitars and pretty loud. In a way, it was quite funny because, in our promotional material, you still could read things like: “Unlike many other musicians who want their audience to reach an excited state, we try to reach a state of calmness and a balance of emotions to create an island of internal peace, in this hectic world of today…” On stage, however, we were not quiet and calm anymore but, occasionally, let it all hang out… We also had a strong desire for more variety in our concerts, and we realized that we would only succeed by making the pieces shorter and more clearly structured. The results were more song oriented compositions as that can be found on “Hallo Rabbit.” Our musical style had changed, evolved, developed.

We started making demo recordings for “Hallo Rabbit” in summer 1973. Regarding the title track, we were thinking of adding some percussion, and we had a rehearsal with an Indian tabla player by the name of Bal Kulkarni who had made recordings with The Beatles earlier. As far as I can rely on my notes, I finished compiling the demo tracks for the album on September 30, 1973.

So, we started recording the songs for the album “Hallo Rabbit” on October 31, 1973, again at Bauer Studios at Ludwigsburg. In the meantime, the studio had updated their equipment, and we were now using a four-track recording machine, which was a big improvement over the stereo-track recorder that had been used for “Imaginations of Light.” For most pieces, we recorded all the instruments in one or two takes and added the vocals in a second step.

We were rather happy with the results of our endeavors, which were musically quite different from our first album, “Imaginations of Light.” Now, it was up to our producer, Klaus Nagel, to find a record label that would be interested in releasing “Hallo Rabbit.” We were sad to know that the PILZ label was not interested in our new product, simply because they could not foresee any high numbers in sales. I guess that, since the PILZ label had started, the management had changed…

Frank Zappa once commented on the artistic decline of the American recording industry in the 1960s. “One thing that did happen during the 60s was: some music of an unusual or experimental nature didn’t get recorded and didn’t get released. Now, look who were the executives in those companies, at those times! Not hip young guys! These were cigar smoking old guys who looked at the product that came and said: ‘I don’t know. Who knows what it is? Record it, stick it out, and if it sells – all right!’ We were better off with those guys than we are now with the supposedly hip young executives who are making the decisions of what people should see and hear, in the marketplace. The young guys [the hippie executives who claim to know what the kids like and what sells] are more conservative and more dangerous to the art form than the old guys with the cigars ever were…”

I think that Frank Zappa’s experience pretty much hits the nail on the head and fits quite well to our own experience. In 1971, we didn’t have problems to get “Imaginations of Light” released. However, in 1973, whenever our producer asked, he was always told that the music of Flute & Voice was “good, but not commercial enough.” I myself heard the same empty phrases when I personally contacted record labels in Paris and even in Manila, in the Philippines – while I always had and still have the opinion that “Hallo Rabbit” was much more “commercial” than “Imaginations of Light.”

What are some of the strongest memories from preparing songs for the second album?

There was nothing that you could call a “preparation” for recording the second album, “Hallo Rabbit.” Basically, we created all the songs, one by one, during the three years that had passed since the release of “Imaginations of Light.” We had played most of the songs for a while on stage already so that they were actually well worked out and rehearsed. We always did it that way, and this is why our recording sessions never lasted long. We just did our thing, as we did it on stage…

Would you share your insight on the album’s tracks?

Before going into the details of the recordings, I should mention that our equipment had changed, in the meantime. My main electric guitar now was a Gibson Les Paul Custom from 1954, with a P-90 in the bridge position and an Alnico V pickup in the neck position. It had been maltreated by its former owner, singer/guitarist Ken Traylor from Joy Unlimited, who had removed its black lacquer, changed the Grover machine heads to Schallers and shaved the neck smaller, a terrifying view for guitar collectors, but the sound of this instrument was simply awesome. This was my main guitar on the “Hallo Rabbit” album. I also bought a Gibson ES-175 from 1961, which I only used for one piece. A newly acquired Gibson GA-6 Lancer amplifier from around 1959-61 went together very well with the Les Paul. As an acoustic guitar, I had bought a rather cheap Japanese Epiphone, probably a FT-133 that, nevertheless, worked quite fine. Hans Reffert used a Fender Stratocaster and still his Vox AC-30 amplifier, as far as I remember. His acoustic guitar was an Ovation that was just in voque, during these years.

“Natural Feeling” represents what the title says. “Natural” means two things: first, simple and straightforward music, second, the natural desire for what boys want to do on their guitars, which is playing loud music. I’m playing the distorted guitar, my old Les Paul going into the old Gibson Lancer amplifier, while Hans Reffert plucks a Fender Stratocaster with his fingers.

“Fairies” mocks the cozy, ideal world of folk songs. It deals with the hidden secrets of a country family where lots of sinister things happen, under the surface. It starts with the beautiful landscape of the “valley of love” and ends with the mother who would prefer her daughter to be a boy and with father and son finally coming out as gay. In this song, I’m singing both voices of the refrain, in playback. I’m playing my Japanese acoustic Epiphone and Hans Reffert, his classical silver traverse flute.

“Dorle” had already been recorded during the sessions for “Imaginations of Light,” but only the guitar part. Originally, this piece was meant to be sung, but my imagination left me, and I was not able to write any lyrics for it. Later, I thought it might be a good idea to have the melody played on a violin. I asked our good friend Dorle Ferber to do the job, and I sang the melody for her, tone by tone. She was perfectly capable of imitating it on her violin, including all the slurs and blue notes of my vocals. In the recording, I’m playing the rhythm on my Gibson ES-330, with my Fender Tremolux, Hans Reffert his Gibson SG Standard, with a Vox AC-30. The awesome sound effect on the solo guitar of Hans Reffert came from a new effect device – I think it was made by Schaller – that was provided by Bauer Studios.

“Hallo Rabbit,” the poor animal, stands for nature, which is sacrificed and slaughtered for the sake of the modern world and human society, a topic that today is more relevant than ever. But there is the promise of future change, the “turning time.” This song is quite a challenge for me as a singer, because, at one point, the melody goes up to a very high note to be sung in head voice. However, in my later years, my voice changed in a way that it is now absolutely impossible for me to reach that high pitch anymore. In the recording, I’m playing the distorted guitar, including the solo on my old Gibson Les Paul Custom, running through my Gibson Lancer amplifier that is set up to the highest volume. Hans Reffert is playing his Fender Stratocaster and a Vox AC-30. This recording really reflects the general live atmosphere of our recording sessions so that you can even hear the clicking sound when I’m switching off the Vox wah wah foot pedal, near the end of the song.

“Scottish Rock,” I think, refers to Hans Reffert’s trip to Scotland. I guess that it was part of Hans’s musical travel diary. Two acoustic guitars, an Ovation played by Hans Reffert and the Japanese Epiphone by myself.

“Little Nemo in Slumberland”… The title of this song is borrowed from one of the earliest comic strips that was designed by Winsor McCay and published at the New York Herald, during the years 1904-1911. Each sequence of this comic strip was about another adventure of a young boy in dreamland. I decided to perform this song without lyrics because I thought this might catch the surreal atmosphere of a dream in a more appropriate way. I played the electric guitar, my old Gibson Les Paul Custom through my Gibson Lancer amplifier, with volume full up, Hans Reffert his acoustic Ovation. The subtle sound effect on the electric guitar, at the end of the song, came from one of the first phaser effect units available on the German market, a Compact Phasing A produced by Gerd Schulte Elektronik in Berlin and again provided by Bauer Studios.

“Strike Another Match” deals with the restless life of a homeless hobo. It is the most complicated song on the album. I played the rhythm guitar twice on my Japanese Epiphone, to make the sound fuller. We wanted to have a kind of “brass section” in this song, but using real brass instruments would have overpowered everything. However, we had an alternative. Hans Reffert had been a member of the Werner Pöhlert Renaissance Ensemble for some time where played a cromome, an old wind instrument from the Renaissance that is related to the oboe. Together with two other members of this ensemble, he formed a 3-voiced cromome section for this song. The second part of the song is completely different. Its long melodic phrases symbolize the beauty of the landscape and the feeling of personal freedom of the hobo on his way through life. While I played the two rhythm guitars again, Hans Reffert, together with Dorle Ferber on violin, played repetitive motives on his Ovation.

“Reprise,” the last piece, is another leftover from our recording sessions for “Imaginations of Light.” It was actually the first version of what should later become the title song “Hallo Rabbit.” The title refers to repeting parts of “Hallo Rabbit,” like a reminiscence, a vague voice resounding from the past, as a kind of musical fade-out of the album. I think this is the only studio recording where I ever used my Gibson ES-175 from 1961, with my Fender Tremolux, while Hans Reffert used his Gibson SG Standard, with a Vox AC-30.

What happened to the third album, “Drachenlieder”? Why was it released in the 1990s when Flute & Voice actually did not exist anymore?

Well, the two of us were very frustrated when our second album, “Hallo Rabbit” was not released, in the 1970s. Flute & Voice actually stopped performing in 1975. But, whatever I did musically, during the following years, our music was always in the back of my mind. However, the eventual release of “Hallo Rabbit” and “Drachenlieder” was purely based on an accident. In 1995, I visited a place called Soundman Shop that was specialized in portable audio electronics, especially in cassette and DAT recorders. Inside the showroom, I ran into a guy, Jack Wiebers, who was just working on a master CD for his own independent record label. We started talking, I told him about the unreleased Flute & Voice material, and we immediately got along well with each other…

“Through its big glass windows, we could look outside into the garden, coated with golden layers of sunlight.”

Together with the four songs of “Imaginations of Light,” the songs of “Hallo Rabbit” (except for “Reprise,” the last one) were released in December 1995 on Jack Wiebers Records, Berlin, 22 years after the album had actually been recorded. When I visited Hans Reffert in Mannheim, during the Christmas break, we were both very pleased about the long overdue release of “Hallo Rabbit.” For both of us, it was truly a relief, as if a heavy load had been taken off our minds. We were inspired, and it didn’t last long until the idea came up that we should also deal with all our other unreleased material.

In the course of 1974, we had composed and arranged a good number of songs. I still remember, when in September, my parents were on vacation, and Hans and myself set up all our stuff inside the living room of my parents’ house. Through its big glass windows, we could look outside into the garden, coated with golden layers of sunlight. It was a wonderful atmosphere for working, and this was the time when we made all the demo recordings for our planned third album that we called “Drachenlieder” [“Dragon Songs”]. It tried to combine the singer-songwriter attitude of “Hallo Rabbit” with the oriental avantgarde sound of “Imaginations of Light,” and all the song lyrics should be written in German. The songs were only recorded in monophonic technology, on a simple Uher reel tape recorder, mixed down from our Shure PA system. I kept all these demo recordings into the 1990s, and after listening to them again, after such a long time, Hans Reffert and myself were really excited and decided to record all the songs again in stereo, this time suitable for another CD release.

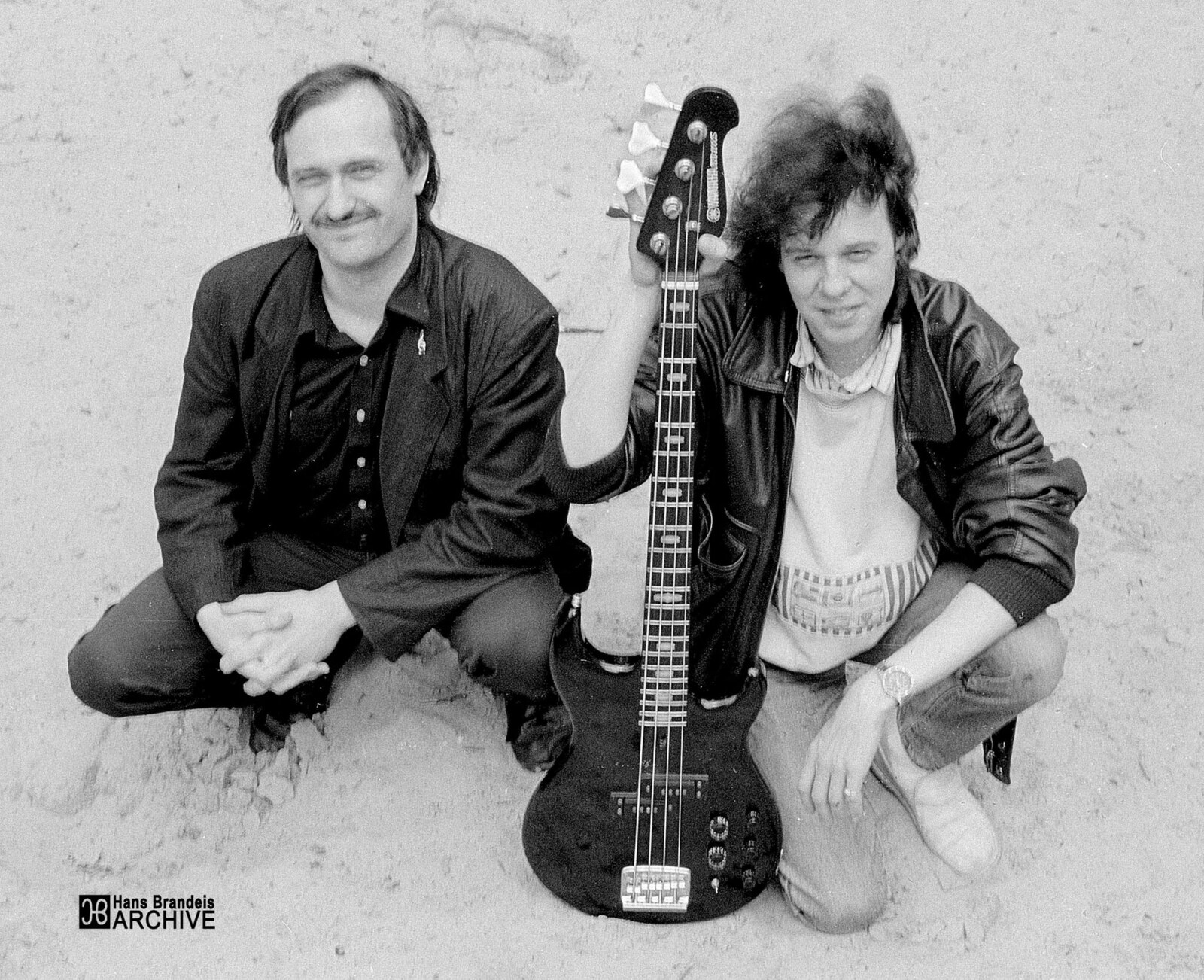

The recordings for “Drachenlieder” happened at the private studio of Adax Dörsam, a guitar player with whom Hans Reffert had already played for some time. They called their duo Schrammel & Slide and also recorded some albums together, basically a continuation of Flute & Voice, however, purely instrumental, without any world music influences, but mainly focusing on plucked guitar related instruments.

The complete production of the “Drachenlieder” album took just a short time. We didn’t want to make it complicated and to conceptualize an album for a present day modern market, but just wanted to record our music in good stereo quality, in exactly the same way as we had played it before, in 1974 and 1975. We rehearsed only for several days, but it was tough because we hardly had any idea anymore how we had played these songs before. We had to listen to the demo tapes, again and again, and learn anew, tone by tone, what we had done. But we also decided to leave out some of those songs from 1974.

We worked at Adax Dörsam’s studio for two whole days and another two half days (February 26-27 and June 3-4, 1996). We recorded most of the pieces live at the studio, in two or three tracks. Even the vocals were not added to a prerecorded playback, but recorded straight and live, together with the instruments. Here are some details about the individual tracks:

“Zwölf Monde” (“Twelve Moons”) is based on a twelve tone melody. I got the idea for this title from the title of a movie: “In einem Jahr mit 13 Monden” (“In a year with 13 Moons”) by Rainer Werner Fassbinder. But the piece has only a twelve tone melody, because there are no thirteen half tones in an octave. That’s how the title came about, just as simple as that… Anyway, this piece is very special to me because it’s a cooperation between myself and my late father: I composed it, and my father arranged it. The original version was meant to be performed by violin, traverse flute, oboe and cello. In the recording, these four parts are played by two violins (by Julia Gallwitz), overdriven electric guitar and bass guitar (both by myself). As far as I remember, I used my self made electric guitar (“The White Sinner”) and an Italian made Dynelectron bass, a copy of the short scale bass made by Dynelectro.

“Wie lange?” (“How Long?”) plays with the expansion of time and, thus, given a musical form corresponding with the lyrics only consisting of one (German) sentence:

“It does not matter

how long we have to wait –

only for whom or for what –

this alone counts.”

The stanzas have no rhythm, and the syllables of all the words are expanded that long that it’s even hard for Germans to recognize the words of the text. As a result, a good number of German listeners asked me which language I’m singing in. This expansion of time illustrates the situation of waiting that seems to last forever. As the melody is stretched in an extreme rubato style, it was absolutely impossible to record the instruments first and add the vocals in playback. Therefore, the song had to be performed life at the studio. I played my Martin D-35 S from 1972. I think Hans Reffert had to borrow his silver traverse flute that he had used before, because he had sold it, in the meantime. The percussion is provided by Mani Neumeier of Guru Guru on a Moroccan drum ţār and other instruments.

“Saskia” is the name of our former producer’s daughter that was born around the time when the piece was composed. Hans Reffert always said that this piece was his musical answer to the jazz composition “Western Suite” by Jim Hall and Jimmy Guiffre. The main instrument is a dobro guitar played by Hans Reffert, I’m playing the acoustic rhythm guitar, Dorle Ferber the violin and Clemens Schuster the cello.

“Ruth’s Blues” is a kind of folkblues played on two acoustic guitars where Hans Reffert takes the lead.

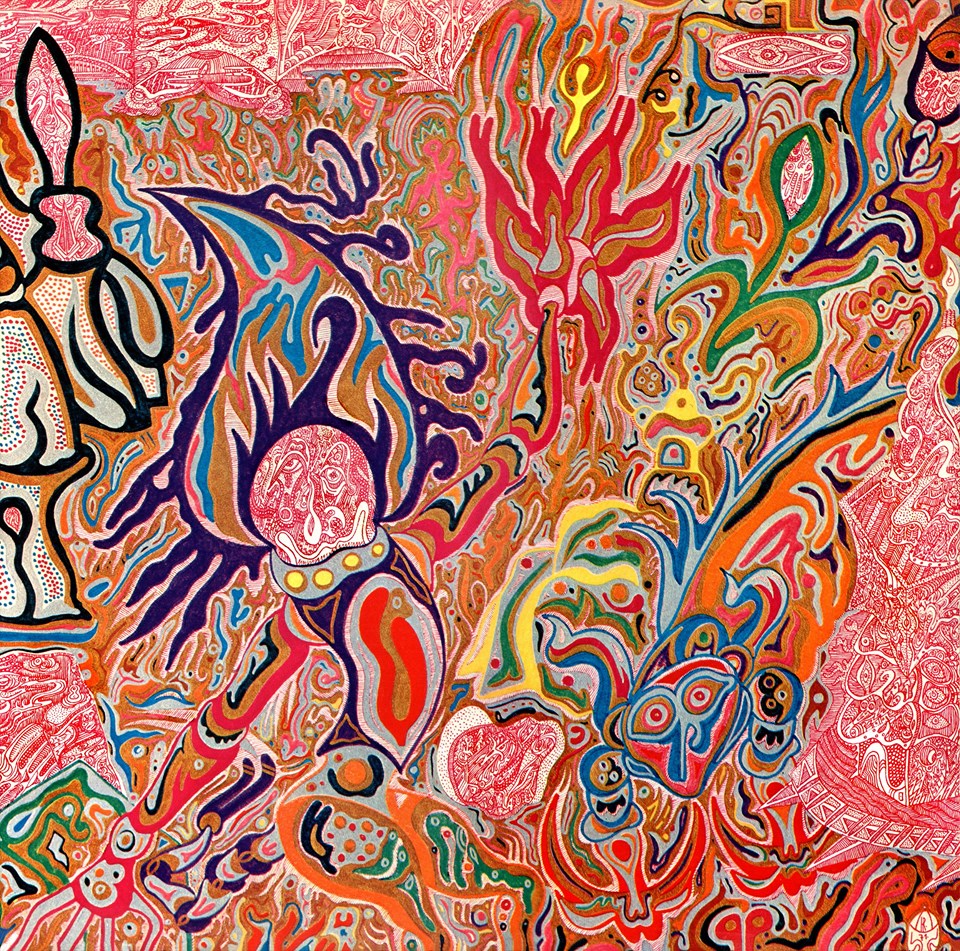

“Drachenlied” (“Dragon Song”) is the most complicated song that Flute & Voice ever recorded, and the story of its creation is also rather complex. When I had a really bad time, in the 1970s, full of severe depression, I was sitting in my room, my head completely empty, no thoughts nor emotions, while making a little drawing. Beside that drawing (which is also shown in the commentary booklet), I wrote some sentences, automatic, like in a trance, and without thinking about their meaning, which I only started to understand during the following weeks. Two years later, I used these text lines as the lyrics for “Drachenlied.” The vocal melody of the song is again rhythmically free, with a lot of melodic ornamentation. It is supported by a drone sound composed of electric guitar (I’m playing “The White Sinner” again), electric guitar with ebow (Hans Reffert), violin (Julia Gallwitz) and cello (Clemens Schuster).

“Das Bier und wir” (“The Beer and Us”) is a kind of folky instrumental for two acoustic guitars and reminds very much of those pieces that Hans Reffert and Ajax Dörsam played in their duo Schrammel & Slide that followed Flute & Voice.

“Bajazzo” is a classical jazz ballad. In the 1970s, when I composed that song, I used to sing the melody in a kind of scat style. However, parts of the song required singing at an extremely high pitch. Now, when we recorded that song, in the 1990s, my voice had completely changed so that I couldn’t reach the high notes anymore. For that reason, the melody now had to be played by Julia Gallwitz on the violin. I used the Gretsch White Falcon of Hans Reffert for the jazz guitar part.

“Vor uns – der Weg – hinter uns” (“Ahead of Us – the Way – Behind Us”). This piece picks up and continues the sitar style that we started with “Imaginations of Light.” However, it’s got a more lively and lighter atmosphere about it, which is born out of the contrasting melodies of sitar and cello. This time, there is also some percussion, which we did not use with sitar before. The extended sounds of the slight dobro and violin go together well with the buzzing and twanging of the sitar. Just like with jazz music, the piece starts and ends with a melodic theme, and everything in between is improvised.

“Dear Presidents” is kind of inspired by American folk blues. It consists of a couple of composed and arranged melodies that surround a lot of improvisation. It is dedicated to the African-American originators of folk blues. “Dear Presidents” is how the musicians called the hard earned dollar bills most of which show the faces of different American presidents, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and others.

“Tinchen Teen” refers to an old teenage girlfriend of mine by the name of Christine, nicknamed “Tine.” The ending “chen” in German means “little.” It’s a very simple song: the first stanza describes the getting together of two lovers, the second stanza their going different ways again…

“Solitude” is just my sitar solo taken out from an alternate version of “Vor uns – der Weg – hinter uns.” We just thought that it would be a waste not to include this. The title plays with words by combining the words “solo” and “etude,” and the resulting word “solitude” fits the mood of the piece quite well.

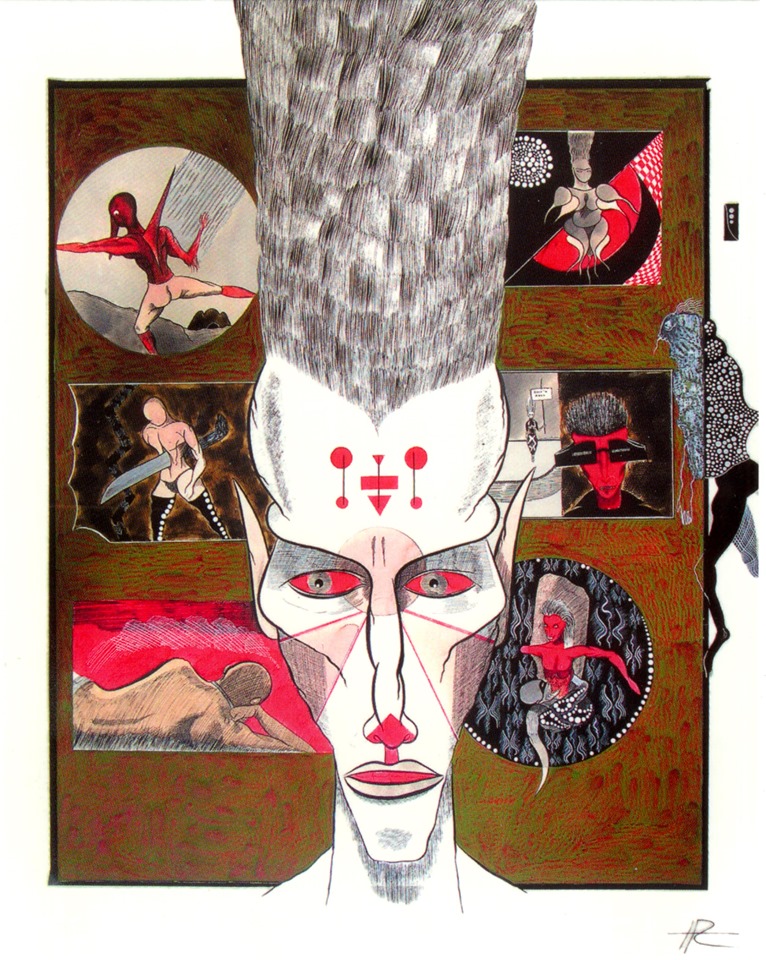

Who is behind all the beautiful cover artwork?

All the cover art as well as all the artwork presented inside the commentary booklets was created by Hans Reffert who is – or better – was a very talented graphic artist. The photographs used on the albums came from different people. And I was the one who made the layout for the booklets of the compact disc editions. By the way, I also wrote all the comments on and inside all the albums.

Are there any other releases that I’m not aware of?

“Imaginations of Light” was actually released four times, three times on vinyl (PILZ 1971, Amber Soundroom 2006 and Wah Wah Records 2016) and once on compact disc (Jack Wiebers Records 1995).

“Heavy Christmas,” a sampler presenting several German Kraut acts was released by PILZ Records in 1971. Flute & Voice were represented with one track, “Ecce Navicula.” This album has also been rereleased on compact disc, on the “Second Battle” label, in 1997.

“Hallo Rabbit” was released twice, together with “Imaginations of Light” on one compact disc (Jack Wiebers Records 1995) where the last track (“Reprise”), however, had to be left out, because of lack of space, and the second time as part of a vinyl double album released by Wah Wah Records in Barcelona, Spain, including the last track “Reprise” plus “Ecce Navicula,” as a bonus track (Wah Wah Records 2016).

“Drachenlieder” was released twice, on compact disc (Jack Wiebers Records 1995) and on vinyl (Wah Wah Records 2016), with identical track lists.

How did your third album, “Drachenlieder,” come about? Why was it recorded in the 1990s?

The fact that our second album “Hallo Rabbit” had not been released did not affect our creativity, of course. We still had enthusiasm, ideas and the desire to express ourselves. But it did not seem to make sense go to the studio and record another album, since no record company showed interest in releasing the previous one. However, as far as I remember, we made the demo recordings of most of the songs for the planned “Drachenlieder” in September 1974.

Which songs are you most proud of?

Actually, we were proud of most of our songs. As far as I’m concerned, from the first album, I really like “Imaginations of Light” (very innovative sound), “Resting Thinking About Time” (very different from mainstream songs, with an awesome guitar solo) and “Notturno” (very expressive and emotional). From “Hallo Rabbit,” I especially like the title song, which became something like our signature tune, and I also like my singing there, with its effortless changes between chest and head voice, and “Strike Another Match,” because of its unusual instrumentation using cromomes etc. On the “Drachenlieder” album, I love “Zwölf Monde” (“Twelve Moons”), because of its complicated 12 tone structure and because it’s the result of my only cooperation with my late father, “Drachenlied” (“Dragon Song”) because, for me, it’s the most artistic piece of music that Flute & Voice ever made, and, finally, “Vor uns – der Weg – hinter uns” (“Ahead of Us – the Way – Behind Us”), which combines an Indian flavor (sitar) with a classical European flavor (cello and violin), a blues flavor (slide dobro) and a northern African flavor (Moroccan tambourine) so that it is truly a world music piece.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

We mostly played in clubs, at vernissages (art exhibition previews), and at youth centers, but also in more unusual locations, like state theaters, the Academy of the Arts in Berlin and during university events. We also had two performances inside prisons (in Wiesbaden and Mannheim) that felt pretty much disturbing, unreal and absurd. Imagine a group of hardcore criminals peacefully sitting together in a room watching two long haired guys play on sitar and bass recorder…

In Mannheim, in 1972, there was a good deal of unrest going on among the young people. An independent youth center had opened, on the initiative of a kind of NGO of people from different strands of life, many of them with some kind of leftist political orientation. This youth center was supposed to be closed down, and that’s when the protest of the young people of Mannheim started. There were some big rallies. One of them ended with a concert of Flute & Voice on the central plaza of Mannheim. We played open air, in front of maybe 1,000 people. There was a lot of excitement and tension in the air…

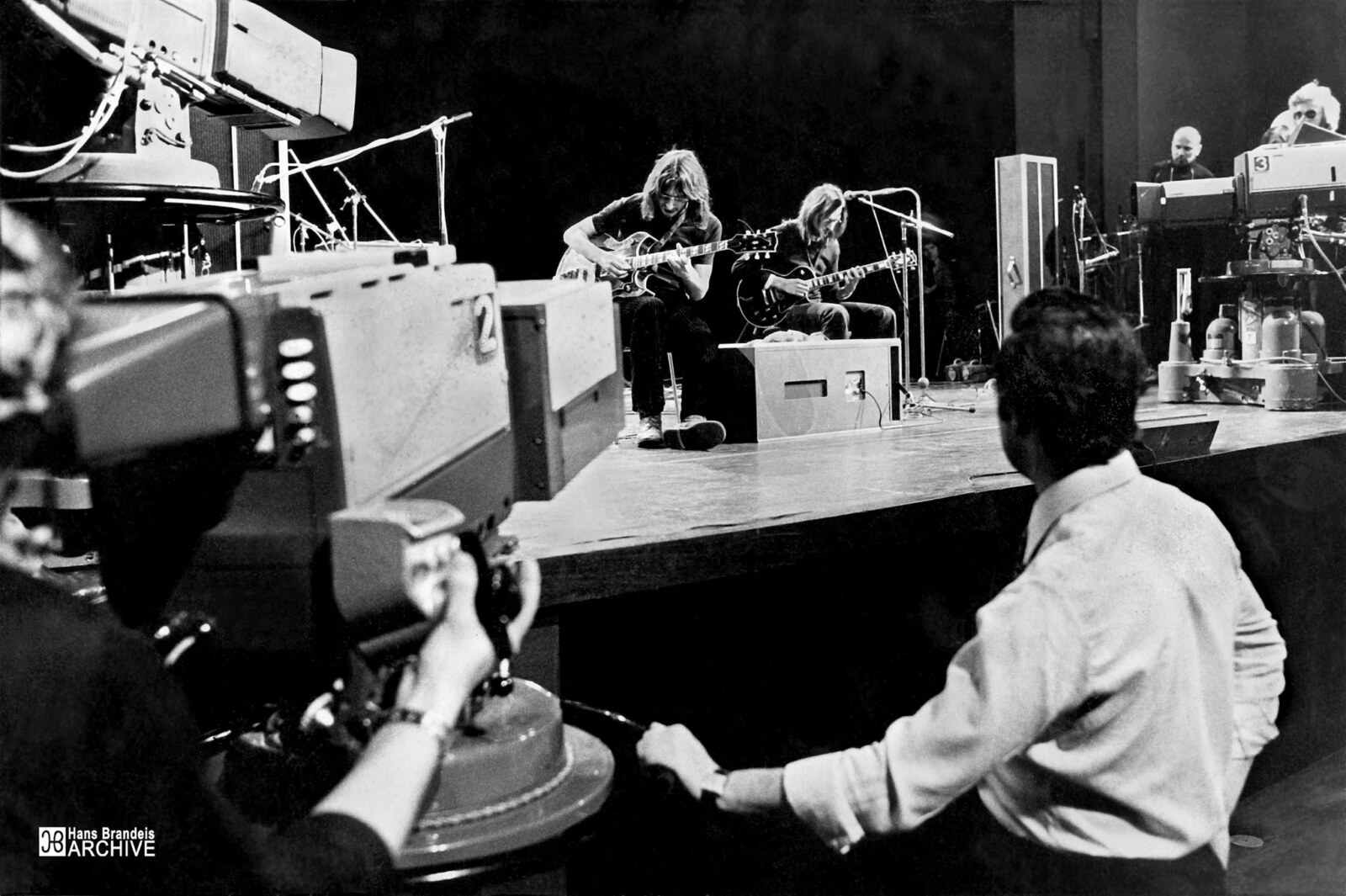

In 1972, we performed during the 13th German Jazz Festival Frankfurt, at a huge concert hall, the Jahrhunderthalle. This concert was broadcast at the German television. Unfortunately, the tapes of this broadcast do not exist anymore, as I was informed by the TV station. But this concert was certainly a highlight…

However, the most memorable gig took place in the small coastal town of Husum, in northern Germany, on May 26, 1973. There was a little rock festival, as part of a so called “Mixed Media Show” that lasted for three days. Participating bands, aside from Flute & Voice were Epitaph, Abacus, and the Canal Street Jazzband, an oldtime jazz band from Hamburg. The concert took place in a big hall, something like a gymnasium. The strong reverb and the echo inside this room were rather disturbing so that loud music was broken down into a sound mishmash. Epitaph were playing ahead of us. There was nothing like transparency in their sound, but people kept on dancing and having fun, any¬way. Then, it was our turn, and when we started playing, the whole atmosphere in the room changed completely. As we did not use any drum set, the reverb of the room responded to our playing in a very different way. The sound that we produced and also heard ourselves was so heavenly that we felt like floating through the room, completely unearthly. We didn’t expect that at all and were also completely startled. So, we just went with the flow. In the meantime, the audience had stopped dancing. Everybody was just looking towards the stage, in awe, and with their mouths open. I looked at them, and I couldn’t believe it because, whatever I did, the audience would follow. This was unreal, and I felt like a spirit that could create a world of his own. The next day, there was a review at the local newspaper, one article about the concert as a whole, and a second article with the headline: “Musical Highlight at Midnight: Flute & Voice”…

You appeared on Roedelius’ album “Jardin Au Fou.”

Slowly, slowly… I think, now, it’s time to talk a little bit about what happened to me after I left Ludwigshafen on Rhine or Mannheim, respectively, and moved to Berlin in April 1974.

Actually, it already started in 1973. I was really restless, at that time of my life, and I started traveling around Germany, visiting old friends and making new friends. I still remember that I once visited Kraan in their farmhouse called Wintrup, which gave the name to one of their albums, and my conversations with drummer Jan Fride about a project that I had in mind. It never happened because, well, I was really too restless, at that time… I also visited a musician friend, Dieter Bauer, in Bavaria. He was originally from Mannheim and, for some time, played bass in the band of guitarist Paul Vincent Gunia, making music for a well known TV series of detective movies. I’m also thinking of drummer Kornelius “Konny” Bommarius whom I knew from my Mannheim days when he played with Twenty Sixty Six And Then, a well known Krautrock band. I visited him in the town of Hamm, in Westphalia, when he played with the band Abacus. During my Berlin days, Konny played with Karthago and, later, after moving back to Mannheim, he pursued a solo career under the name Beckenhower. (That’s playing with words, as “Beckenbauer” is a famous soccer player in Germany, “Becken” means “cymbals,” “Hauer” is somebody hitting something, and then, “Beckenhower” also reminds people of the name “Eisenhower” where “Eisen” means “iron.”)

But in 1973, Konny Bommarius was still living in the countryside, in a village called Echt¬hausen, in Germany’s Ruhr district. There was a kind of hippie and music community residing at “Rittergut Haus Echthausen,” a big, castle like building and former residence of an old noble family of knights. That’s where he stayed, together with his wife and his little son. And he made music with guitarist Hannes Schroer and bassist Mick Brehmen. Their band was called Echthausen as well. I visited them many times and always stayed there for a couple of days. And then came the day when the band went into the studio and recorded two songs for their first single. They invited me to come along with them, as a guest musician. I joined in recording a song titled “Love Is All Around” where I played the second guitar and sang all the vocals, partly three or four voices. It was the very first and only time that I ever sang and played a hard rock song. I just tried to sing as if my balls were hanging out of my mouth, and it was great fun for me just fooling around. We did a lot of nonsense that all still can be heard at the end of the recording. I still have a rough mix of it. There was also a piano player whose name I don’t remember anymore. Later on, I returned to Echthausen with musicians from Berlin, for a rehearsal vacation, so to speak… I’m sad to say that all members of the band, Konny Bommarius, Hannes Schroer and Mick Brehmen have passed away, in the meantime…

“I simply didn’t want to follow any of the current styles in rock, jazz or whatever kind of music.”

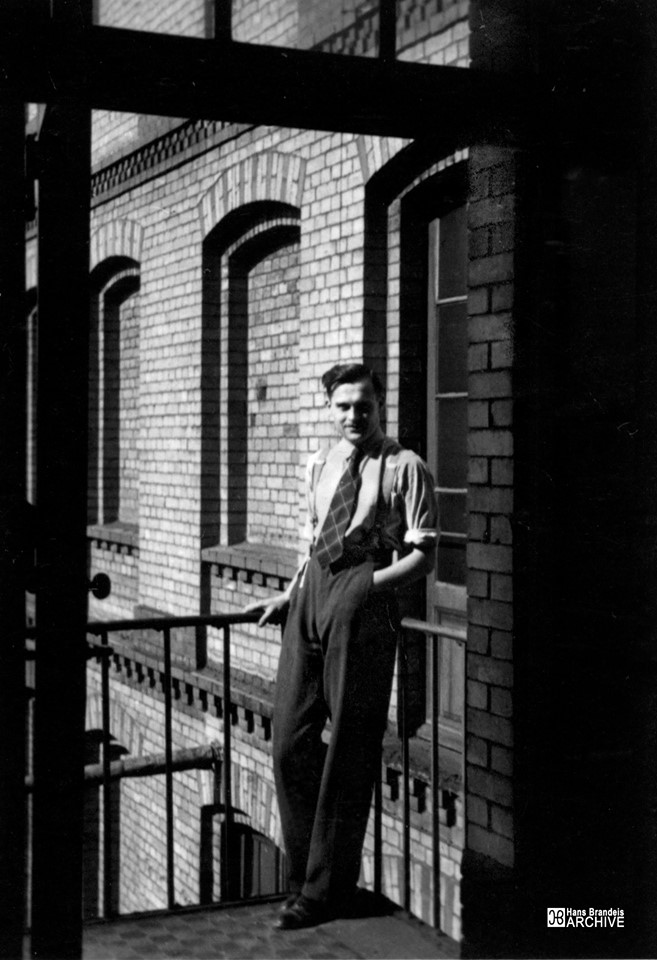

My main reason to move to Berlin was my interest in studying ethnomusicology at the Free University of Berlin. (We will talk about that later.) Nevertheless, I had kept my rented room back in Mannheim so that I had a place to stay whenever I returned to Mannheim during the university vacation or semester breaks. Moving to Berlin, however, meant that working on the Flute & Voice project became more and more complicated because I regularly had to travel, back and forth, and even started to neglect my studies at the Free University.

As the music of Flute & Voice and my collaboration with Hans Reffert had been quite unusual, it turned out pretty hard for me to find musicians in Berlin with whom I could identify as birds of the same feather and who were not so much into mainstream music. I simply didn’t want to follow any of the current styles in rock, jazz or whatever kind of music. The quarter of Kreuzberg, located near the Berlin wall, was one of the centers of Berlin’s Turkish population. The rents for apartments there were pretty low, because the owners of the houses didn’t spend any money at all to maintain them. As a result, the condition of the houses, the safety situation, and the quality of life in general in this part of the city were declining at a rather fast speed. Wrangelstraße was the street where the old barracks of the former police headquarters had been located. These were big, abandoned buildings, almost ruins, but still safe enough so that their rooms could be rented out as practice studios for bands by the city administration. The “Wrangel Kaserne” offered some awesome opportunities because, after your own rehearsal, you could just walk from room to room and listen to lots of bands, all rehearsing different styles of music. I only remember a few names of bands and musicians whom I saw rehearsing there, like Curly Curve, Axel “Ax” Genrich (interview here), Marquee Moon, Metropolis, Os Mundi, Friedemann Graef Quartett, Rockcypfel and Karthago. The latter gained some wider recognition and, for some time, had former bass player Glenn Cornick (interview here) of Jethro Tull as their band member.

In one of these rehearsal studios, I was also practicing with two very young musicians, both just 18 years old, Hans-Dieter Lorenz on bass and Andreas “Andy” Oelker on drums. They were both still going to school, and they were very talented. But I was already 25 years old, and the age gap between myself and them was really an obstacle in communicating with each other about the meaning, philosophy and different styles of music. They had been playing with another guitarist before, Hanno Rinne, of their own age, who had left Berlin for studying abroad, in the US, for one year, as an exchange student. As these two young men were very loyal to their friend, and they kept on waiting for Hanno to return, there was always a strange atmosphere of temporary collaboration between the three of us. Eventually, Hanno returned to Berlin. We rehearsed for a while as a band of four, but the project soon fell apart, first of all, because Hanno turned out to be incredibly jealous towards me. Later on, he returned to the US and studied jazz guitar at the renowned Berkelee College of Music. A couple of years later, when he was back in Berlin, I heard him perform traditional jazz with a trio, and he played really very well.

Anyway, my collaboration with Hans-Dieter Lorenz and Andreas Oelker resulted into three recordings with a kind of jazz rock flavor that I’m planning to release, sometime in the future. At this point, another Berlin connection comes in. because one of my musical friends was Michael “Fame” Günther who played with Agitation Free. He was actually a founding member of the band. And he was living together with a couple of friends in a flat sharing community. One of them was Udo Arndt, former guitarist of Os Mundi. Years later, he should become a very successful sound engineer and producer of German bands and artists like Nena, Rio Reiser, Curt Cress, Ton Steine Scherben, Spliff, Rainbirds, Juliane Werding, Stefan Waggershausen and others. At that time, he was in a one year practical traineeship at the recording studio of the Evangelischer Rundfunkdienst (ERD), the radio broadcasting service of the Lutheran church in Berlin. He was very systematic in learning his new profession as a recording engineer so that he invited many Berlin bands, giving them a chance to produce demo recordings of high quality, for free. The equipment at the studio was all state of the art, but there was no multitrack recorder because this was not needed for radio broadcasts. It was therefore only possible to make live studio recordings, mix them down two stereo on the spot and record them on two tracks.

So, there was this chance to make recordings at the ERD, together with my two school boys. Our trio had no name, just a kind of working name, either Huckepack or Orpheus. On May 9, 1975, I recorded three of my own compositions, together with Andy Oelker on drums and Hans-Dieter Lorenz on bass. During a kind of jazz rock piece, we were supported by jazz pianist Bernd Gruber, also a very talented guy. I still remember that, during the recording of “Heile Welt” (“Cozy World”), while I was working hard on my guitar, I heard all kinds of weird piano sounds, in my back. So, I looked over to Bernd to see what he was doing, and I saw that his head and whole upper body had submerged into the open grand piano, with both hands working their way through the mechanics of the instrument, diving into the intestines of a musical organism… In everyday life, Bernd Gruber was actually a rather quiet and introverted person and, just a few months after the studio session, he committed suicide, I think, by hanging himself. That was more than shocking… After finishing school, Hans-Dieter and Andy both studied music, double bass and percussion, respectively, and became free¬lancing musicians, here in Berlin.