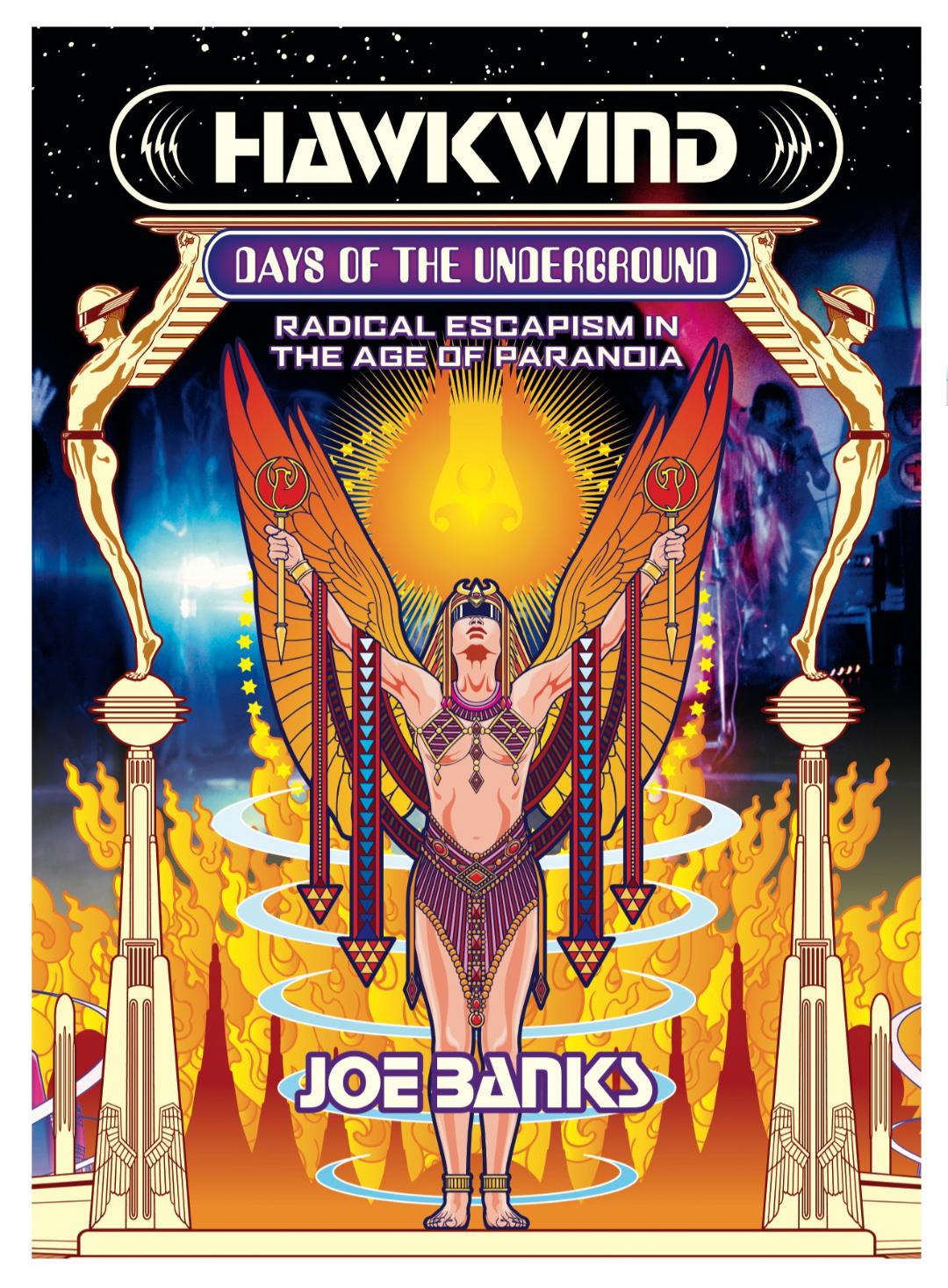

‘Hawkwind: Days Of The Underground: Radical Escapism in the Age Of Paranoia’ | Interview with Joe Banks

‘Days Of The Underground’ is a decade-long trip into the music of Hawkwind, exploring the ideas and concepts that fuelled the band during their classic 1970s period, and speaking to the crew that manned the ship.

Avatars of the underground, figureheads of the free festival scene and heralds of punk, Hawkwind were one of the bands that defined the 1970s. At the height of their artistic and commercial powers, Hawkwind channelled and amplified the era’s psychic tenor via a science fiction sensibility, mind-blowing visuals, and their unique brand of deep space psychedelia.

“Hawkwind embody an alternative history of the 70s”

Would you like to talk a bit about your background?

Joe Banks: I’ve been a serious music fan since the age of 13. After school and university, I worked in music shops, sang in a band and made my own music. This of course meant that I was effectively broke most of the time, so in my late 20s, I bit the bullet and got a “proper” job in PR, which I did as a full-time career until 2013. Since then, I’ve been looking after my daughters while freelancing in PR. Oh, and passing myself off as a music writer.

How did you first get interested in rock music?

The classic story of having an older brother with a large record collection! I started off playing his Slade singles, and ambiently soaking up the music from his bedroom – Pink Floyd, Queen, Deep Purple, Judas Priest…

“They were musically unique”

What was the first album you heard by Hawkwind?

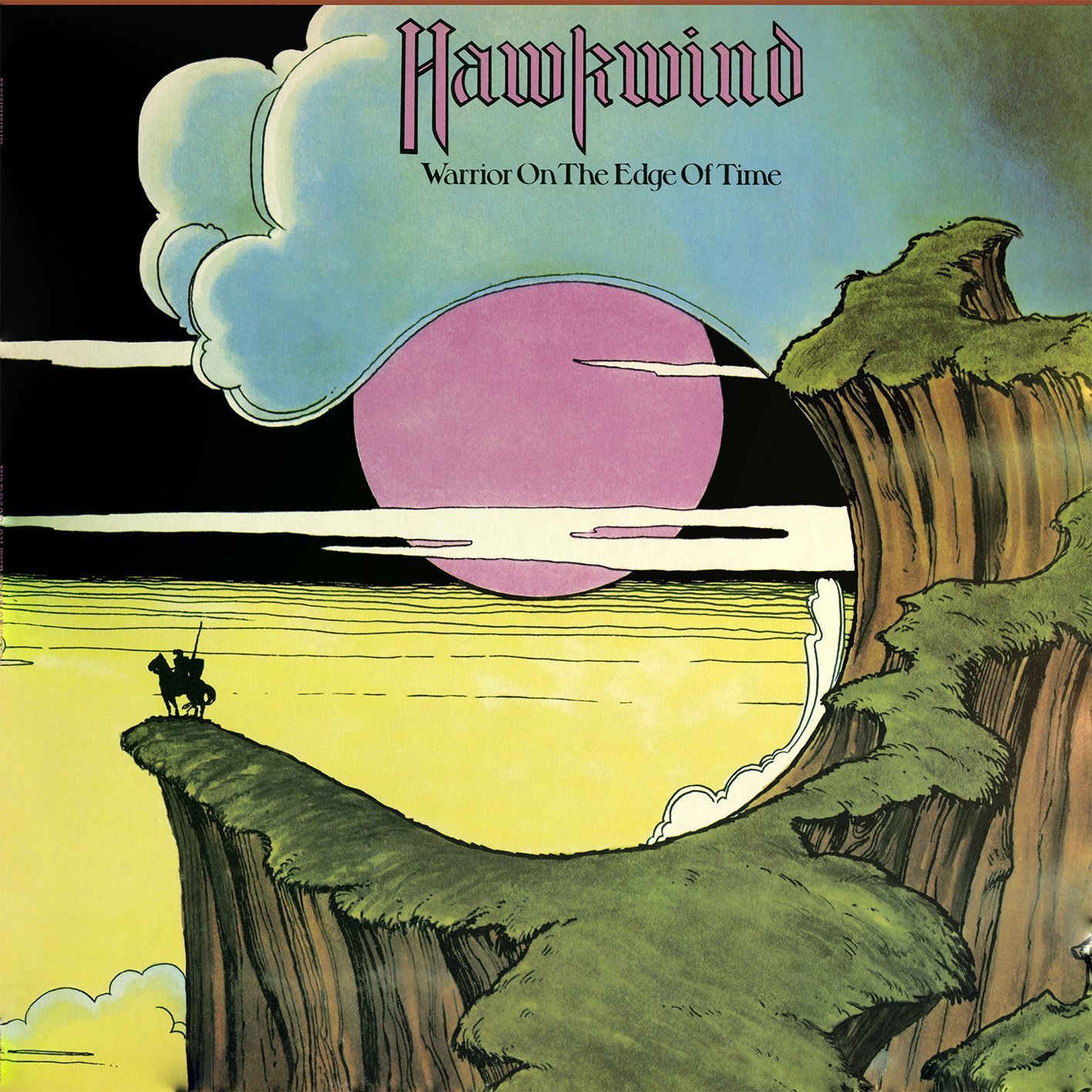

‘Warrior On The Edge Of Time’, again courtesy of my brother. Everything about it – from the fold-out sleeve to the driving, Mellotron-soaked music – seemed incredible, and different from those other bands.

Your book focuses on Hawkwind. As one of the most innovative and culturally significant bands of the 1970s, what’s most unique about them?

For a start, they were musically unique – there may have been parallels with some of the contemporary stuff coming out of Germany, but they were completely out on their own in Britain. But it wasn’t just that they sounded different – they acted differently as well, in the way that they were fiercely opposed to the “star trip” and how the traditional music business worked. They toured the country relentlessly and built up a genuine bond with their audience, inviting them to become part of a shared mythology. Just like the Beatles, they were a “revolution in the head” for many people, something which persists to this day.

How do you define “space rock”? What is the main difference between space rock and let’s say psych/prog rock in your opinion?

Good question. Hawkwind may not have been the inventors of space rock – I think Pink Floyd, however much they’d deny it, probably got there first –but they’re certainly the band who ran with the concept and made it their own. So to a certain extent, “space rock” for me is always partly defined by “how much does this band sound like Hawkwind?” ie. heavy riffage, propulsive rhythms, raw electronics et cetera. There also has to be a science fictional element, even if it’s just in the artwork and/or titles, though ideally not too naff! Psych and prog feed into space rock – but whereas psych can sometimes be too whimsical or diffuse, and prog too performative, proper space rock has both density and forward motion. For example, I would cite Slift’s last album ‘Ummon’ as a real modern exemplar of space rock.

“‘In Search Of Space’ is where they first nail their particular brand of space rock”

What are essential milestones when it comes to their discography?

For me, ‘Warrior On The Edge Of Time’ and ‘Space Ritual’ are their two defining albums. But ‘In Search Of Space’ is where they first nail their particular brand of space rock. And then we have the genius of Robert Calvert, as best experienced on ‘Quark, Strangeness And Charm’ and Hawklords with ’25 Years On’. That’s what’s so great about Hawkwind, there isn’t just one or two classic albums, but a whole spectrum of brilliant music throughout the 70s and beyond.

What inspired you to write ‘Hawkwind: Days Of The Underground: Radical Escapism in the Age Of Paranoia’?

I’ve always loved Hawkwind, but it was the strongly positive response to an early article I wrote for The Quietus about Space Ritual – which attempted to place the band in the cultural context of the “apocalyptic 70s” – that first made me think there was something more to write about them beyond the two perfectly decent biographies that were already out there. So it was a desire to pull all the socio-cultural threads together – the idea of the “underground”, the science fiction mythology, their influence on punk et cetera – that really got me started. In many ways, Hawkwind embody an alternative history of the 70s.

How long did it take to complete this massive project, from conception to publication?

A long time, with many missed deadlines! As I said, the initial seed for the book came from that article from 2013. Strange Attractor, my publisher, gave me the green light to begin writing ‘Days Of The Underground’ at the end of 2015. I started properly in March 2016, and delivered a ludicrously bloated first draft two years later. There was then another year and a half of editing, sourcing visual material et cetera. It was theoretically ready around the end of 2019, but we hit some design issues, so it didn’t end up going to the printers until mid-2020. And then Covid-19 mucked up the distribution! It officially came out in October 2020.

The UK scene was completely different to the US.

If you compare the original US and UK countercultural/psychedelic scenes, the US is much more politicised (Vietnam, civil rights et cetera) than the UK, which tends to be more about personal liberation et cetera. Core US bands such as the Grateful Dead, Quicksilver Messenger Service and Jefferson Airplane came from a folk/blues background whereas the British bands were inspired directly by the example of the Beatles, as well as incorporating more leftfield jazz and classical influences. Crucially, because of the relatively compact size of the UK and the news/trend-driven immediacy of the weekly papers – Melody Maker, NME et cetera – music developed and mutated much quicker over here compared to the US. Britain went rapidly through various scenes during the 70s while America was still listening to the Eagles! Hawkwind really thrived in this environment – for all the jibes that they always sound the same, it’s clear (to me at least!) that they adapted to this state of flux much better than a lot of their contemporaries, and were, for instance, a key inspiration for the punk & post-punk movements.

The pioneering free festival movement started in the UK in the 1970s. Hawkwind was an essential part of it. Would you like to discuss this unique movement?

Along with the Pink Fairies, Hawkwind were certainly there at the start, playing free outdoor gigs in and around Ladbroke Grove, particularly under the Westway arches (as photographed on the fold-out sleeve of ‘In Search Of Space’). The Canvas City performances outside of the 1970 Isle of Wight festival were also crucial to Hawkwind’s identity as heroes of the underground, while the festival itself lit the touchpaper of the free festival movement when the fences came down on the final day. Hawkwind’s philosophy of just turning up and playing was certainly an inspiration, and even after becoming a big top 20 band, they went on to appear at many of the 70s’ key free festivals – Windsor, Watchfield, Stonehenge et cetera. As such, they were absolutely talismanic to the whole movement, and continued to be during the Peace Convoy years of the 80s and the outdoor rave scene of the 90s.

“Hawkwind were responsible for bringing the good news of the counterculture to every corner of Britain in the early 70s”

“Hawkwind took the underground to the provinces and beyond”…

To a large extent, Hawkwind were responsible for bringing the good news of the counterculture to every corner of Britain in the early 70s – not just their music and show, but also free copies of IT and Friends/Frendz magazines, and if Nik Turner is to be believed, copious amounts of liquid LSD! Sure, it was possible to hear the music of the underground on John Peel’s Top Gear and you could (sometimes) read about it in MM and NME, but Hawkwind were the counterculture come to life and there was a good chance they’d be playing your town soon. At the time, most commentators had written off “the alternative society” as a failed experiment, but Hawkwind kept proving them wrong – just one of the reasons why the media was often quite hostile to them.

How involved were Hawkwind members in this book?

More than I had originally envisaged! I hadn’t intended to interview as many people as I did, but one connection led to another, and I couldn’t say no. I spoke to many of the 70s crew, with Nik Turner and manager Doug Smith being particularly helpful. It’s a real honour to be able to pick up the phone to people whose names you’ve pored over as a teenager on the back of album sleeves! There isn’t a formal interview with Dave Brock in the book, but I did speak to him and he knew what I was doing. (This is where the interview I conducted with him during the writing of the book was used: link)

What would be some of the most interesting facts about the band that are not widely known?

Goodness, where to start? Depends on your existing Hawk knowledge, as there are quite a few people out there who know everything. For just the general rock music fan, probably the main takeaway is just how big the band were for a few years in the 70s (72-75), something which tends to be overlooked now – they had a million selling single and headlined what’s now Wembley Arena, for example! But one of my favourite pieces of extreme trivia is that modern classical composer Michael Nyman was once in the frame to replace Del Dettmar!

Did you learn a lot of new stories and facts through your research?

Yes, though often it was trying to untangle what had become quite a convoluted story, as I wanted the book to be as factually correct as possible. But sometimes surprising new information would come to light – for instance, Paul Rudolph’s assertion that Dave Gilmour had a lot more to do with the production of ‘Astounding Sounds, Amazing Music’ than just remixing ‘Kerb Crawler’. Tracking down previously unknown film from the Wembley Empire Pool show was also quite a buzz. And finding and speaking to Pamela Townley, Robert Calvert’s second wife, was a complete revelation.

Is there anything we have not addressed that readers should be made aware of?

Please visit the site of the book at daysoftheunderground.com, which is actually an online companion to the book rather than just a promo for it. For instance, you’ll find an extensive collection of live and vinyl ads, a picture gallery full of rare images, and just about every scrap of Hawkwind on film from the 70s. Hours of entertainment!

What will be your next project?

I’m currently working with Strange Attractor on what I hope is going to be long-running project involving lots of writers as well as myself. I’m also continuing to review for Prog, Shindig! and Electronic Sound magazines.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Thank you for having me! It’s Psychedelic! Baby Magazine has done a fantastic job of speaking to so many of the “forgotten” heroes of the music underground.

Klemen Breznikar

Joe Banks Official Website / Facebook / Twitter

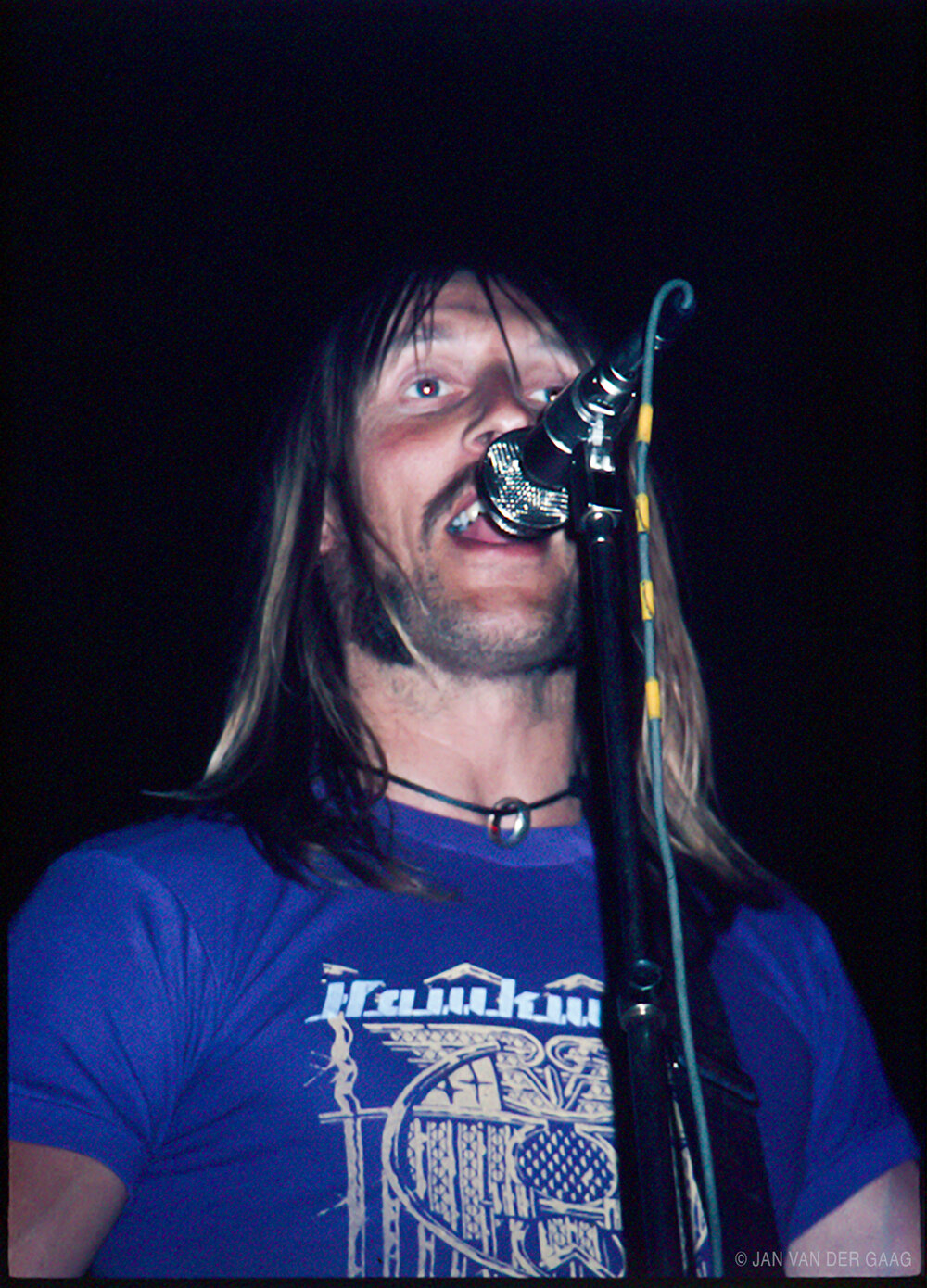

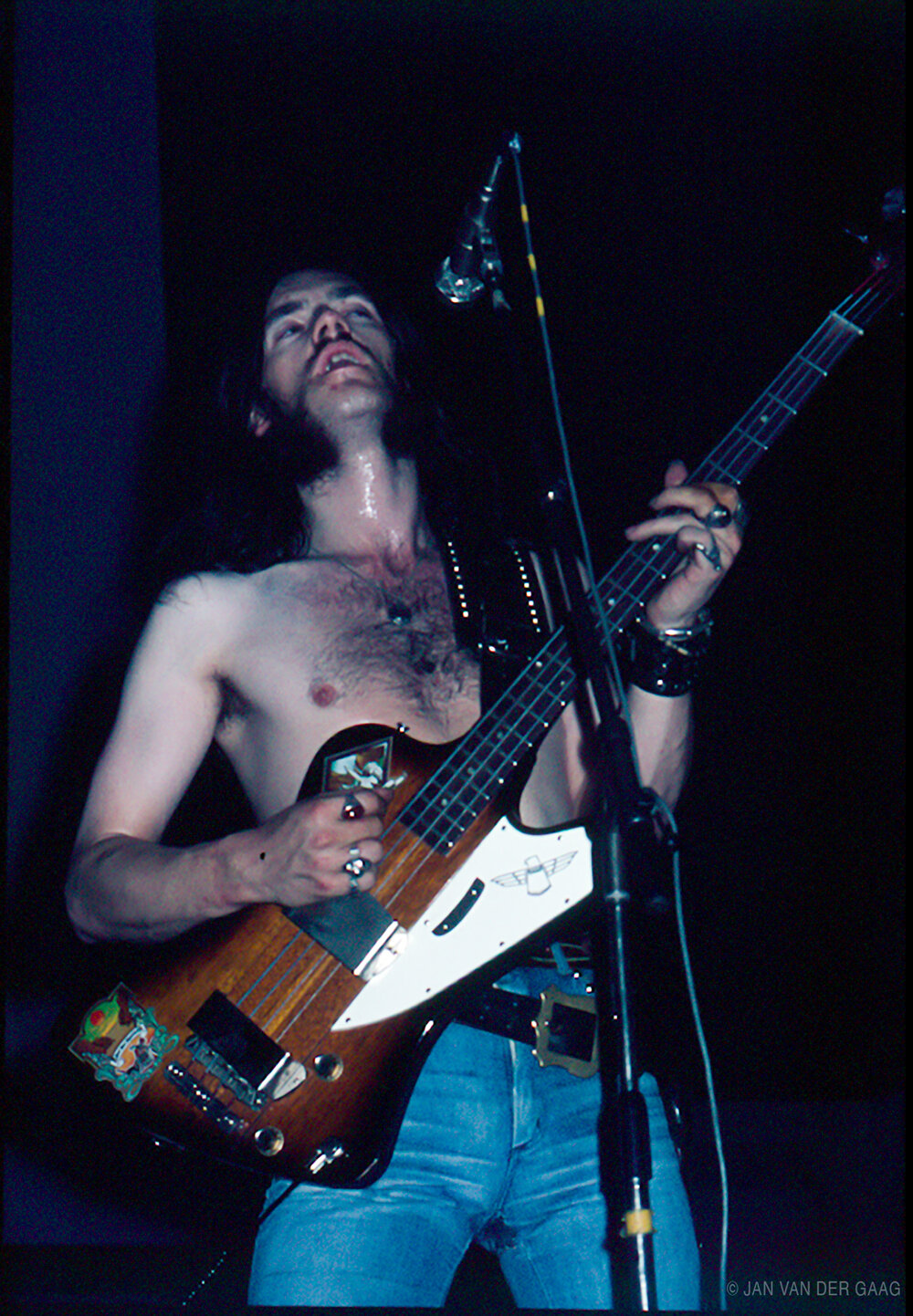

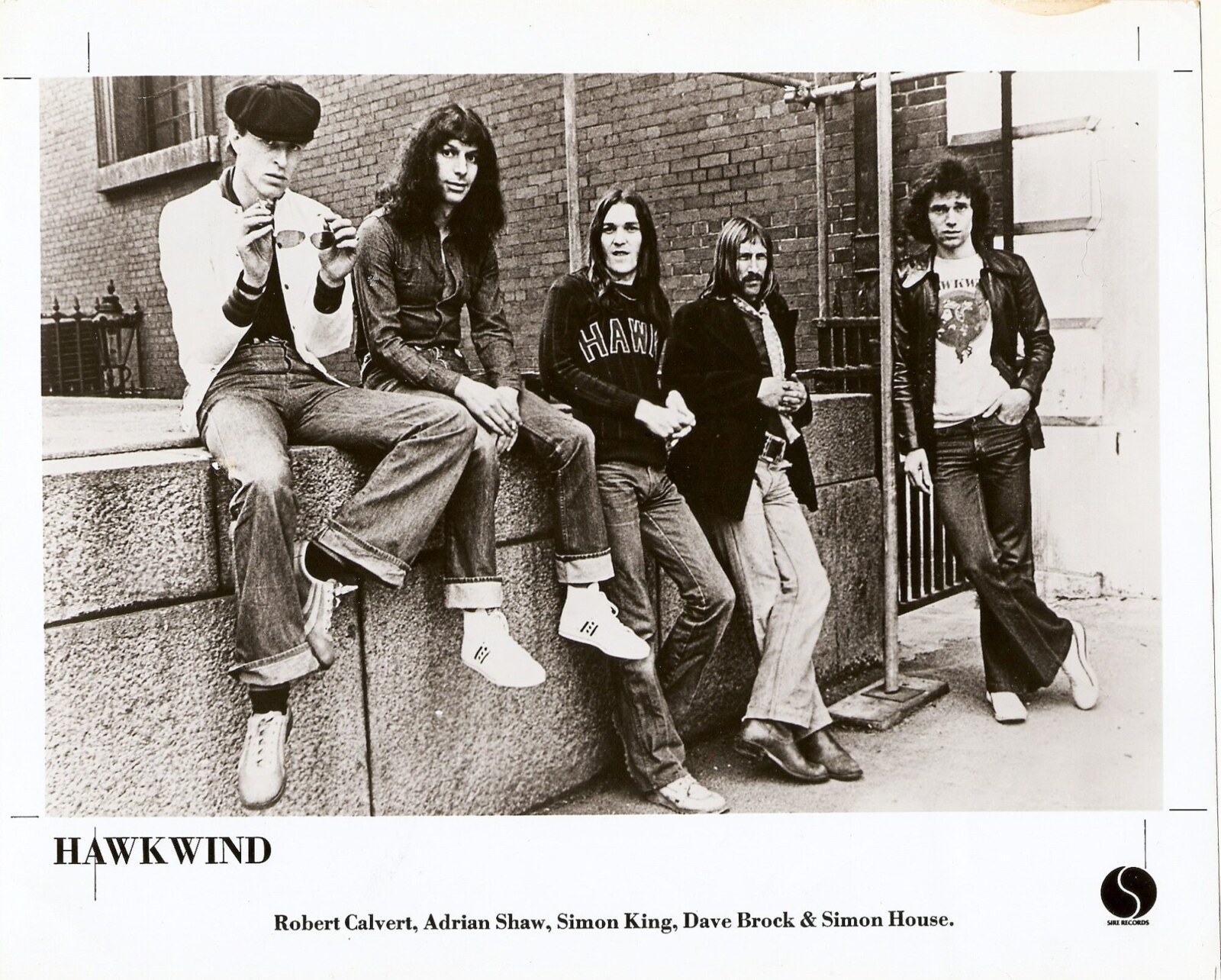

Headline photo: Hawkwind promotional photo | Copyright: Michael Scott Collection

Adrian Shaw talks about Magic Muscle, Hawkwind and The Bevis Frond …

Nice to see the seminal band featured here with a new book on them out.