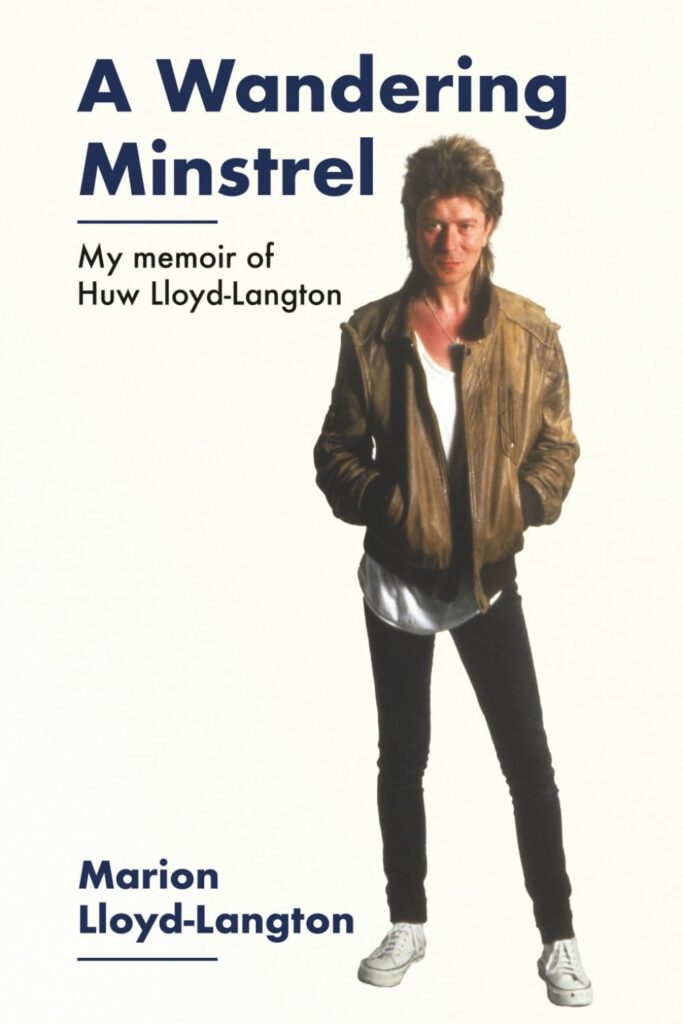

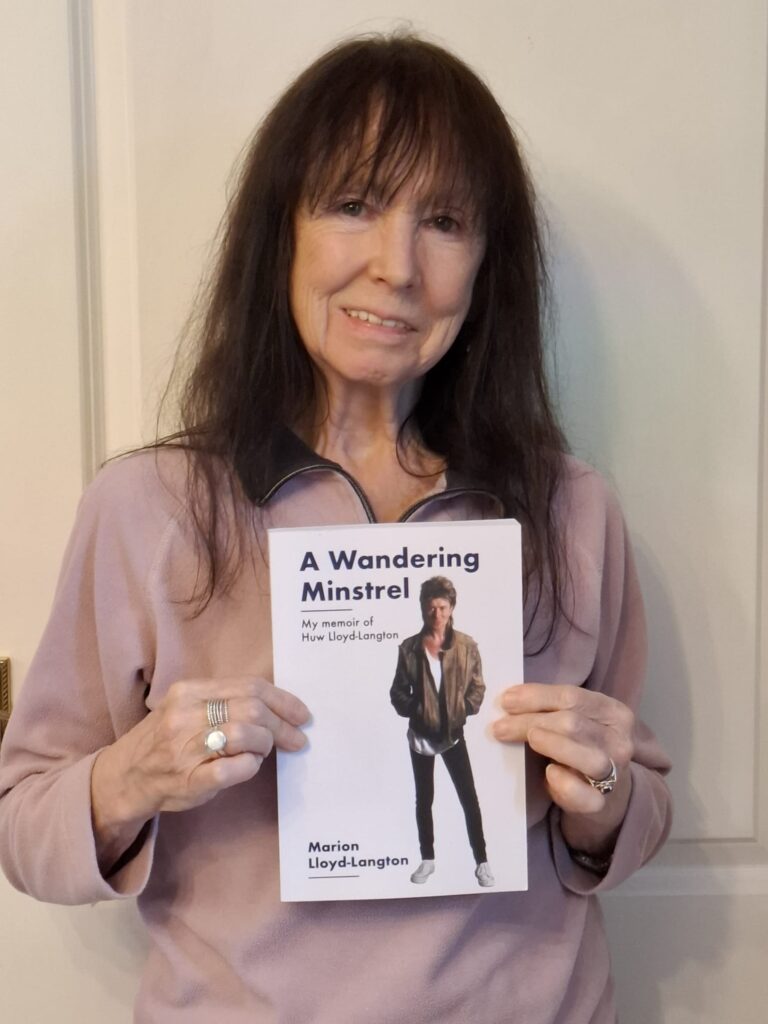

A Wandering Minstrel: Marion’s Intimate Memoir of Guitarist Huw Lloyd-Langton and the Early Sound of Hawkwind

The late guitarist Huw Lloyd-Langton, whose contributions were integral to the early sound of Hawkwind, is the subject of A Wandering Minstrel, a memoir authored by his long-time partner, Marion.

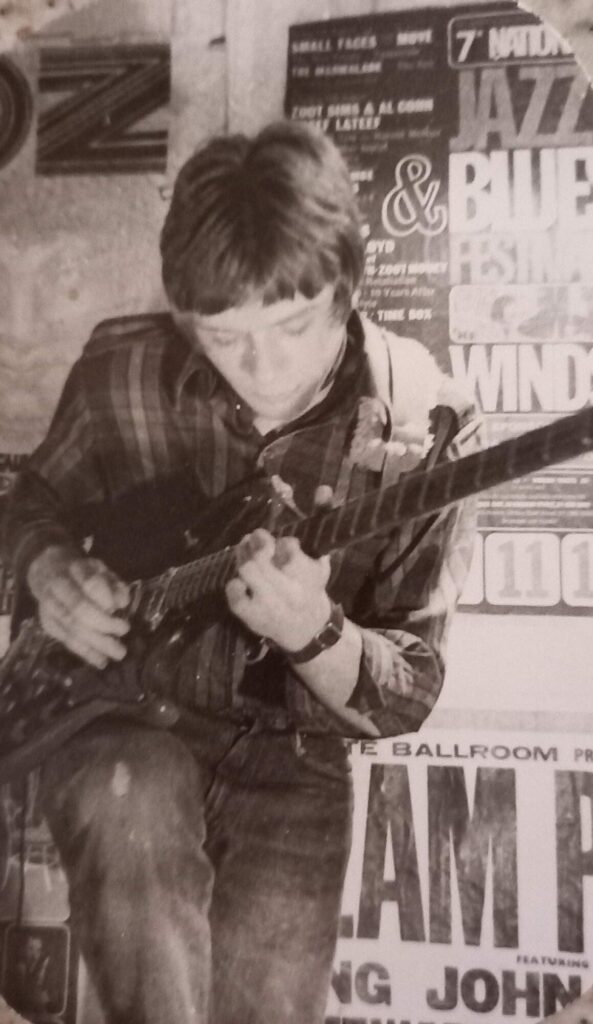

Far from a conventional biography, the book weaves together Huw’s musical journey, their shared life, and a deeply personal narrative of love, loss, and faith. Huw, often called a “road gypsy,” loved the buzz of live gigs and much preferred the freedom of the stage to the rigid confines of a studio, though his recordings are still highly admired. Marion’s memoir brings him vividly to life through anecdotes, personal letters, photographs, and caricatures, highlighting both his technical brilliance and gentle, generous nature. From his early blues influences to his multiple stints with Hawkwind, Huw’s influences was rooted in sincerity, curiosity, and a devotion to those around him.

In summation, A Wandering Minstrel functions as both a heartfelt homage and a significant primary source, offering unfiltered insights into the private life of a notable figure in British underground. By allowing the reader to finally see the man “as he really was,” the memoir offers an essential map of the complex interplay between a musician’s creative life and the vast reaches of space.

“I could not separate our private and working lives. Thus, yes, it formed organically as I began writing.”

Marion, thank you for agreeing to this interview. Your memoir, A Wandering Minstrel, offers a profound and intimate look into the life of Huw Lloyd-Langton, a musician whose career was as complex and varied as his character. The book is not merely a chronicle of his musical journey but a testament to your shared life, a narrative woven with threads of deep personal experience, faith, and the often unpredictable nature of the music industry. I want to delve into the process of creating this remarkable document and explore some of the key themes that emerge from your heartfelt prose.

The memoir is not a linear, chronological biography but rather a series of interconnected chapters, often moving between different periods in Huw’s life, your life, and your shared experiences. This structure feels like a deliberate choice, mirroring the “wandering” nature of Huw’s career. Could you elaborate on this decision? Was it a conscious artistic choice from the outset, or did the narrative form itself organically as you wrote?

Marion Lloyd-Langton: When I started writing the memoir, I intended to write purely about Huw’s early life, which would then lead into his whole career. However, it soon became very clear I could not separate our private and working lives. Thus, yes, it formed organically as I began writing. This was a surprise to me and a little scary, as I had always considered my role in our lives as the back-room girl. I could only hope I could write a book people would enjoy reading.

You state in the acknowledgements that writing this book was “a long hard emotional ride.” Given the depth of personal hardship you recount—from the loss of your daughter Louise to Huw’s battle with Legionnaires’ disease and later his cancer diagnosis—how did you navigate the emotional toll of revisiting these memories? Did the act of writing prove to be a form of catharsis?

Yes, writing this memoir was a long, hard, emotional rollercoaster. I had to take time off at various points to consider if what I was doing was the right thing to do. But when I picked it up again, the words flowed, and indeed, writing did prove to be cathartic in more ways than one. As an example, prior to writing this memoir, I could not bear to listen to any of our own albums or anything Huw had contributed to. But I had to listen to our various albums and revisit our songs to be able to add memories and write the discography. It broke the cycle of fear and heartbreak. I can now listen and appreciate Huw’s work without getting upset.

The narrative is rich with direct quotes and anecdotes from Huw himself, as well as from his friends and musical collaborators. How did you gather and organize this information? Were these conversations and stories you had already documented, or did you reach out to people specifically for the purpose of the book? This collaborative approach seems to be a cornerstone of the memoir’s authenticity.

I reached out to various musicians Huw had worked with who were also personal friends. I went up and down the UK to record their memories of Huw. Not only was it lovely to visit and spend time with them, but it also felt like we were back in the early days where we shared laughter and so many memories. I also had a huge trunk of memorabilia, which included set lists and itineraries of virtually every gig Huw had ever played at. But I wanted real input from some of the amazing musicians Huw had the pleasure of working with over the years.

You also include a selection of Huw’s own caricatures and personal photographs. These visual elements provide a poignant counterpoint to the written text, offering a glimpse into his inner world and his unique sense of humor. How important was it for you to include these personal artifacts, and what do you feel they reveal about Huw that words alone could not?

Yes, Huw’s caricatures were and still are very important to me. Huw was an amazing artist, not just an amazing musician. From day one of our being together, he never bought a card from a shop. Birthdays, anniversaries, Christmas, and other special days—Huw drew, sketched, or scribbled cards for me. I loved them all. I collected them for over 40 years and ultimately, after Huw left the planet, I designed a website to put them all on (www.huwligans.com). I selected one or two for the memoir. Huw’s amazing sense of humour sustained us through many difficult times. I chose photos for the memoir which I thought would also reflect musical history and our lives together.

The title, A Wandering Minstrel, is a recurring motif throughout the book, originating from Huw himself. In your view, what did this phrase mean to him, and how do you feel it encapsulates not just his musical career but his entire philosophical approach to life?

This is an interesting question. When I chose the title for the book, I had no idea Huw had already given himself that title. To me, he had always been that—“have guitar, will travel.” It wasn’t until I interviewed engineer Paul Smith, who recorded the last LLG album ‘Hard Graft’ and many more tracks for Huw, that he told me Huw had called himself “A Wandering Minstrel.” Serendipity! His approach to life was simple: treat everyone as you would like to be treated. He was a kind, gentle soul, and it was what I loved about him. When he put his hand on my shoulder, I could never describe the soft touch and the warmth that flooded through me.

You describe Huw as a “road gypsy” and a “purist” who preferred playing live over recording in a “sterile and inhuman” studio. This tension between the energy of performance and the controlled environment of the studio seems central to his identity as a musician. How did he reconcile these two worlds, and what was his philosophy on the purpose of making a record versus performing for an audience?

Huw always preferred working on the road and live performances as opposed to studio work. He liked the camaraderie of musicians working on stage with him. He said they would bounce off each other and it allowed for creating a sound the audience would appreciate. When he performed solo gigs, he would always ask a flautist or bongo player to join him. He said he didn’t feel so alone on stage. In the studio, he was often the last to go in to record. But despite his reluctance to record, somehow his beautiful guitar work shone through.

Huw’s musical journey was marked by a constant series of associations, often short-lived, with various bands. Yet he returned to Hawkwind multiple times. What do you believe was the unique gravitational pull of Hawkwind for him? What made this particular “marriage” different from his other musical relationships?

What made it different from all the other enterprises Huw undertook was that Hawkwind was always the Mother Ship, an invisible string across the many years. I did say recently to Dave and Kris, I never quite understood the strong link, but it was always there. I now believe it was part of a Universal plan for Huw. Actually, for both of us. We loved it when they did well without him, and they certainly did with Dave Brock as the leader and Kris with her amazing managerial skills among her other talents.

The memoir touches on Huw’s spiritual journey, particularly the profound experience after the Isle of Wight Festival. You detail how this led you both to Christianity. How did this faith influence his music and your lives together? You mention the song “Got Your Number” in this context. Can you speak to how his spiritual beliefs manifested in his songwriting and performances?

Yes, our faith in Christ culminated from the horrid experience of Huw being spiked at the Isle of Wight Festival. Our faith sustained us throughout our lives, both in the good times and the dark times. God stepped in when Huw needed him most, and I was fortunate enough to be gathered up with him. I have always been thankful for that. From then on, our lyrics reflected what we felt, both in living on this earth and the beauty of a heaven where we both hoped to retire. In the good times, I would watch Huw on stage, and to me he was a shining star—a little angel with the most amazing sounds emanating from his fingers. I was, after all, his biggest fan.

“Writing did prove to be cathartic in more ways than one. It broke the cycle of fear and heartbreak.”

Throughout the book, you emphasize Huw’s humility and generosity, noting how he would encourage other musicians and share his knowledge. What do you think motivated this selfless approach in a famously competitive industry? Was it a reflection of his character from a young age, or something he developed over his career?

When I met Huw, after our initial not-so-good encounter, I was struck by his quiet, serious nature. It took me a while to understand he was a genuinely nice person with a great sense of humour. He reminded me of my Dad, who was a man of few words but totally trustworthy. After meeting his parents and hearing about his childhood, I understood he had always been that way. His students loved him and said his gentle manner and encouraging ways gave them confidence. He was the same with the musicians he worked with, occasionally taking a back step to encourage them to shine on stage too.

You detail Huw’s extensive work as a guitar teacher, from his early days at Ivor Mairants Music Centre to later at the Kilburn Community Centre. The anecdotes from his students, like Louis Eliot, are particularly moving. What did Huw find most rewarding about teaching, and what do you think made him such an effective and beloved mentor to aspiring musicians?

Ooh! Huw said he hated teaching, but I knew that wasn’t so. Huw had a sense he wasn’t good enough. He simply never wanted to let them down. That was down to his humility. But I knew he was an amazing teacher, as is reflected in what one or two students said about him in the memoir. I have learned over the years even the top world singers and musicians suffer from a lack of confidence before they go on stage, but that disappears once they start performing.

Huw’s guitar sound is iconic and instantly recognizable. You mention he was not a fan of effect pedals, preferring to adjust tone controls and pickups. Could you shed light on his technical approach to achieving that distinctive sound? How did he balance his blues influences with the psych (anarcho) rock demands of bands like Hawkwind?

Huw loved valve amps because of their warmth and because he could manipulate the sound emanating from them via tone controls and pickups and get the sound he wanted from his guitar easily, as opposed to digital amps and pedals. As a young lad, he simply loved blues music and was fortunate enough to see his favourite blues bands in various clubs in London. Blues music was an inspiration to him and always the base of all his work. He simply extended his knowledge of blues chords and tempos by learning all 48 different scales: 12 major scales, 12 natural minor scales, 12 harmonic minor scales, and 12 melodic minor scales. This structure allowed him to move from traditional blues music to playing rock music and, of course, gave him a distinctive guitar sound. He often played around with major and minor chords to create a harmonic sound.

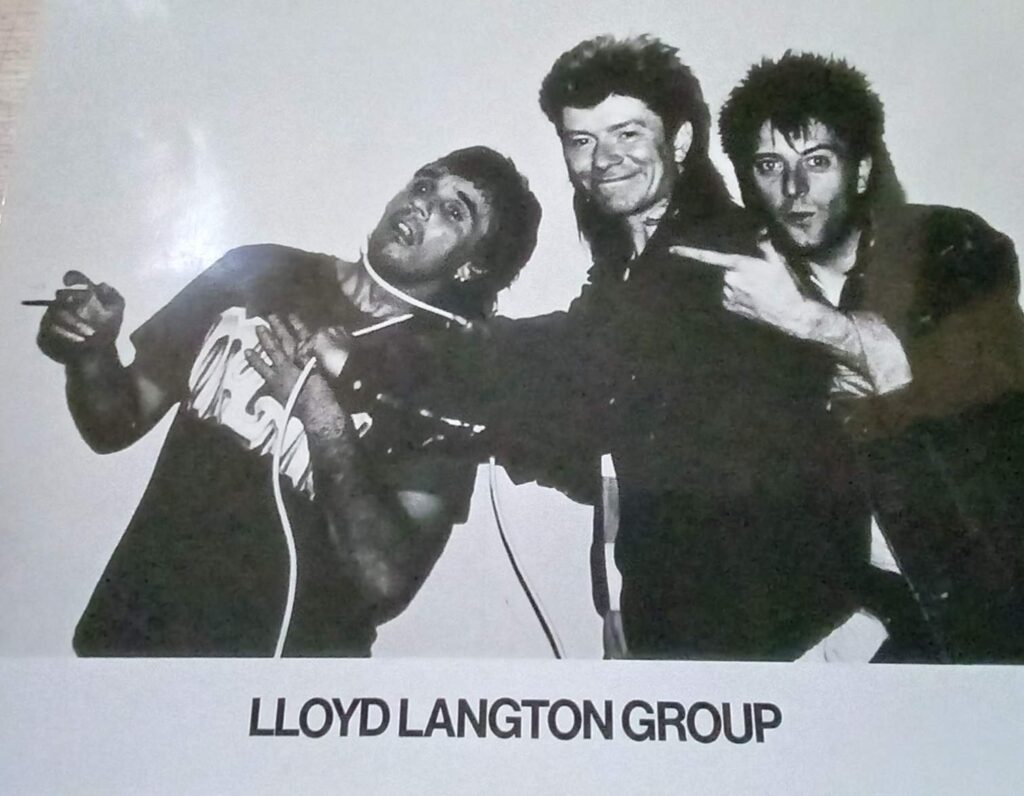

The book is titled A Wandering Minstrel, and yet your own presence as a “working woman” and an active partner is powerfully felt throughout. From managing his own band (LLG) and tour logistics to your work at RSO and other professions, your role was far from passive. How do you view your own identity in this story, and what do you think it says about the nature of partnerships in the music world?

As I said earlier, initially I viewed my role in our partnership as the back-room girl, holding the fort together and allowing Huw to follow his career. But as time went on and Huw’s various different partnerships in the music world occurred, my role became a much more hands-on managerial position: setting up tours, press, booking venues, hotels, etc. It occurred naturally over time, without any given plan. Without major management in the background, it was my next step. It was no hardship for me to take on this role. In my experience, behind any successful musician or band there has to be a good manager willing to go the extra mile.

The section on the ‘Chronicle of the Black Sword’ album and tour is a fascinating look at the theatricality of Hawkwind. As someone who was there, what was it like to witness the band fully embrace a fantasy concept, and how did Huw’s contributions, like ‘Moonglum’ and ‘The Sea King,’ fit into and shape this artistic vision?

‘Chronicle of The Black Sword’ was a testament to Hawkwind’s all-round role of theatre and music. It was a magical performance. Michael Moorcock’s Elric saga books were indeed an inspiration for this whole concept. Writing the lyrics for ‘Moonglum’ was easy for me, the character reminded me of Huw, and Elric reminded me of Dave Brock, the leader. Huw wrote the lyrics and music for ‘Sea King.’ Both tracks on the tour were received really well by the audience.

Your friendship with Dave and Kris Brock is a constant, enduring theme. The account of Kris helping you after Huw’s passing is particularly poignant. It suggests a bond that went far beyond musical collaboration. Could you talk about the foundation of this friendship and how it endured the many lineup changes, professional disputes, and personal challenges that are often part of a band’s history?

Yes, I am fortunate to have Dave and Kris still in my life. Two loyal friends and great companions. I guess the enduring friendship goes back many years. I originally met Dave at a Hawkwind rehearsal in late 1968. Huw loved and admired Dave as a fantastic musician and songwriter, but also as a person. Despite differences over the years, and there weren’t that many, that friendship lasted throughout Huw’s and my life, whether he was in or out of Hawkwind. The same should be said about Kris, who I met in 1979 when she was dancing with the band. Later she was fire-eating! An amazing spectacle. She also designed the Black Sword costumes for the tour. Then later still she was stage-managing and managing Hawkwind (she still does). As I said in the memoir, Kris and my world trip really cemented our long-lasting friendship. Later, her amazing contribution to Huw’s funeral surpassed any kindness anyone could ever give to a friend in need. They say a mother’s love is unconditional; I would say the same about true friends.

The tragic event of Huw being spiked with LSD at the Isle of Wight Festival is a well-known part of Hawkwind lore, but you provide an unvarnished, deeply personal account of the aftermath. What prompted you to share such a private and painful experience in such detail? What do you hope readers will take away from this specific story?

I wanted to set the record straight, as there had been murmuring on the net that Huw had made it all up to gain notoriety. Dear me! Also, I wanted, hopefully, to give readers encouragement amidst illness, chaos, and uncertainty. What happened to us was nothing short of a miracle.

The memoir concludes with a discussion of Huw’s guitars. You explain how parting with them was an act of both love and acceptance. Can you describe your personal relationship with these instruments? How did seeing them being cleaned and restored by Ben Crowe bring you a sense of closure?

Well, I was not allowed to clean or polish Huw’s guitars; he had special polish for that. He said ordinary polish destroys strings and wood. That was his job. He fondly named his two favourites: Lizzie was the 10th Anniversary Les Paul, and Howie was his Howard Roberts guitar. Both guitars were bought by Don Arden at the factory, which was then in LA when Widowmaker were touring there in 1976. When Ben Crowe collected all Huw’s guitars to restore and send them for auction, I felt desolate. To me, I was saying goodbye to another part of Huw. But they had been in storage for years, neglected, and I knew Huw would have been really upset to see that. They needed to go to a good home, and they did.

Your poem “The Wandering Minstrel” is a beautiful and fitting tribute to Huw. How did writing this poem help you process your grief? The lines “He wasn’t perfect none of us are / But he will always shine like a star” are especially powerful. What are the key imperfections you remember, and how did they ultimately contribute to the man you loved?

When one truly loves a person, you see all their imperfections, and real love covers all of that. In fact, it was the moment I realised no matter what Huw did, I would always forgive him. He never did anything so awful I couldn’t forgive him. True love isn’t blind; it is the opposite. We both made mistakes along the way, but we were honest with each other, so all was forgiven.

The book’s discography is extensive and provides a valuable resource for fans. Looking back at this vast body of work, from Hawkwind’s debut to his final acoustic and classical albums, which specific track or album do you feel best represents the entirety of Huw Lloyd-Langton as a musician and a person?

What represents Huw as a musician, songwriter, and singer, I would say all of the above. The whole catalogue encompasses our entire lives together in the music industry. Hard Graft and his final solo classical album were probably the hardest for him, as he was so ill. But he did it, which was a testament to his enduring spirit and the legacy he left.

What do you believe is Huw Lloyd-Langton’s most enduring legacy? Is it his iconic guitar work, his influence on other musicians, his gentle nature, or something else entirely? What do you hope readers of your memoir will carry with them after they turn the final page?

What is Huw’s most enduring legacy? All of the above, but most of all the loyalty and love he gave to me, our friends, the musicians he worked with, and the fans who made his life’s journey worthwhile.

Klemen Breznikar

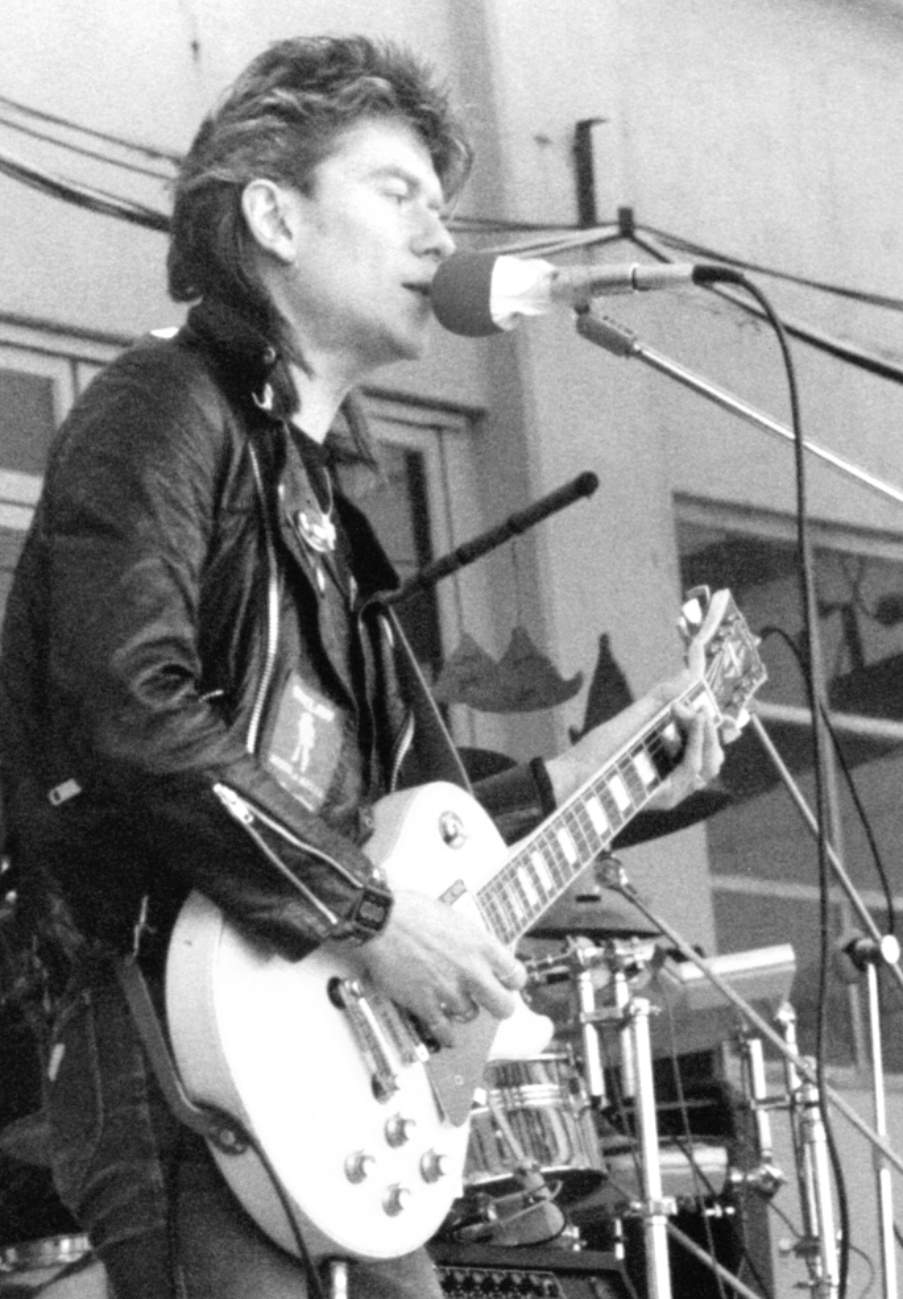

Headline photo: Huw Lloyd-Langton performing with Hawkwind, 1986. Photograph by Oz Hardwick.

A very special thanks to Ian Abrahams for making this interview possible.

Huw Lloyd-Langton Website