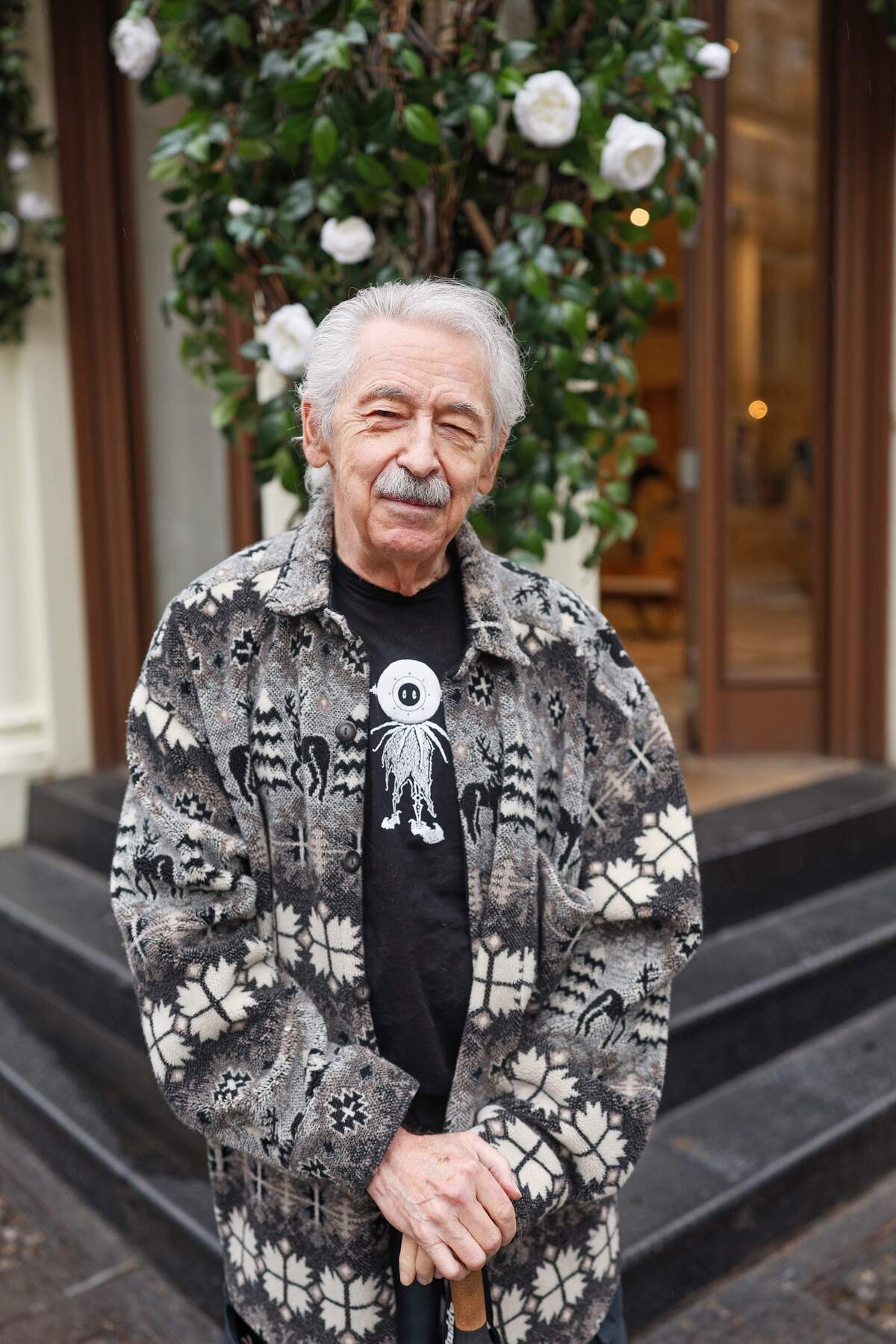

Peter Stampfel, a Holy Modal Rounder, Picks Up the Pieces on ‘Song Shards’

Peter Stampfel, co-founder of the seminal folk-psych ensemble The Holy Modal Rounders, remains American music’s most joyful provocateur.

For over six decades, Mr. Stampfel has inhabited a world entirely his own, defined by a “different freedom” that privileges ongoing improvement over commercial expectations.

His new album, ‘Song Shards,’ is a vivid inventory of this singular philosophy. It functions as a mosaic, stitching together verses inspired by Dorothy Parker, stoic aphorisms, and vintage commercial jingles—”interesting cultural artifacts,” as he calls them—into a subversive whole. The record is a testament to an artist who once incited a park brawl in 1960 simply for playing a folk standard “wrong,” a moment that solidified a lifelong ethos. “All my life I’ve had an intense desire to fuck shit up,” Mr. Stampfel says. With ‘Song Shards,’ he continues to do just that, offering a portrait of an artist who is not merely enduring, but evolving. Highly recommended!!

“All my life I’ve had an intense desire to fuck shit up.”

‘Song Shards’ is a wonderfully idiosyncratic title for an album that feels like a mosaic of your vast experiences and perspectives. Could you elaborate on how you settled on this title? Did it just pop out when you saw how all these new and old tunes fit together, or was it something you had in mind from the get-go?

Peter Stampfel: The title came at the end of the process, which I think I laid out in the liner notes—Dorothy Parker, the basic inspiration when I set her four-line poem to music, the Muses suddenly hitting me with short, succinct bursts of lyric, stoic aphorisms showing up shortly after, and the trove of recorded jingles from 2018 being obviously closely related. Soul jingles was suggested by a band member, song shards popped up last, I’ve decided to discard soul jingles in favor of song shards, and using song shards as a general title category as well as a specific title for non-stoic or commercial jingles. I’ve found a great one from Lao Tze, and have several new ones in the pipeline, including a beauty from recent Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright Brendan Jacob-Jenkins. Hope he gives permission!

You’ve been pretty open about how weed helped get a lot of these new songs going, even giving a shout-out to “ganja” in ‘Muses Nine.’ So, after all these years, including that stretch where you were clean, how has your whole creative process changed? What’s it like making music with cannabis as your “ally” these days, compared to other times?

I use it mainly to make playing more fun/wanting to play for a longer time/it eases my dysphonia, which has generally gotten a lot better. I almost never use it for non-musical reasons. Also, with the potency nowadays it just takes 4/5 tokes.

That ‘Muses Nine’ story, where “The Muses Nine are mighty fine” just slipped out during a gig and then became a whole song, is pretty cool. Since you’ve spent so much of your life improvising and just being in the moment on stage, do those kind of lucky accidents happen often? And do you have any secret tricks for remembering those fleeting bits of inspiration, or do you just trust they’ll come back when they’re ready?

If I don’t write them down right away, they’re good as gone. When they happen onstage, they’re good as gone. Many times people have mentioned things I said on stage that I didn’t remember. Usually they were pretty funny.

Throwing in those old jingles like ‘Castro Convertible’ and ‘Wisconsin Super Service Stations’ on the album is such a Peter Stampfel move – it’s like a little trip down memory lane! What is it about these old bits of advertising that grabs you? And how do you turn something so, well, commercial, into a piece of art that feels so… you? Any other forgotten sounds you’re thinking of bringing back to life?

Jingles were designed to be memorable. Many had genuinely appealing melodies. Sometimes I actually enjoyed the products. Many were strange. Often they were all of these at once. I’ve always considered them interesting cultural artifacts. Anybody remember the Japanese on the a polisher on an 80s Shonan Knife record? It’s really pretty! Why aren’t jingles systematically collected?

In ‘You Are the Product,’ you’re talking about those aphorisms and how you still find yourself comparing yourself to others. It’s wild to think about, especially since you’ve had such a singular career, with critics even putting you up there with Bob Dylan. How do you deal with all that comparison stuff, both from others and in your own head?

I just try to disengage when it pops up, which it does several times a week. BTW I posted on the Richard Thompson FB site: Thompson is worth 20 Eric Claptons, and took a ton of heat. And a few agreements.

‘Swell Hells Bells’ is a fantastic example of how you can take something old, like a round, and just totally make it your own, even dropping in that iconic Harry Belafonte bit. What’s your secret to taking these existing melodies or phrases and giving them such a fresh, often cheeky, new spin? Is there a special joy in messing with what people expect?

All my life I’ve had an intense desire to fuck shit up.

You were right there at the start of the Greenwich Village folk scene back in ’59, way before anyone even coined terms like “freak-folk.” So, looking back, how do you see independent and experimental music having changed over the years? Do you hear echoes of what you were doing way back when in today’s bands, or does it feel like a completely different world now?

It is a completely different world. Two things—re freak folk, go to the Perfect Sound Forever site and read my freak folk piece, originally written for the brilliant Michael Hurley fanzine, Blue Navigator, around 2008. I’m sure it’s the best piece on the subject ever written. I’d love to be proven wrong. Other thing—back in the aughties, Eli Smith and I—forgot who else came with—Walker Shepard?—were invited to a Harry Smith festival in Milford, PA. For a couple days, everyone played songs from the Anthology. With one or two exceptions, everyone’s take on every tune was twisted, bent, and/or freaky in some way or other. My take was that freak folk had become the default setting. And that was almost 20 years ago.

What makes you want to work with someone new, and what do you think are the magic ingredients for a really great musical partnership? Any dream collaborators you’ve still got on your list, or maybe some unexpected projects you’d love to dive into?

The three main things that appeal about playing with someone new are fun to play with, into goofiness, and better than me. Of course that does not mean that I might be better than them in some tiny way or other, but basically, folks that play better than me. Which is actually not too hard. Dream collaborator #1: Richard Thompson. #2, I adore playing double fiddle with band member Stephanie Coleman (we’re playing double fiddle behind Yo La Tengo for their Hanukkah snow). I’ve also played amazing double fiddle with Jackson Lynch (check out his multi-genre masterpieces on Jalopy Records), and I’ve talked to them both about doing triple fiddle. 2026 for sure!

What’s it feel like to still be making “righteous stuff” at this point in your life? Do you feel a different kind of freedom in your music now compared to earlier in your career?

Not sure what you mean by righteous stuff. If you mean high or undiminished quality output, I’ve been striving all my life to try to get better, and have been obsessed all my life with how almost all artists tend to go downhill quality-wise. Willie Nelson being a very rare exception. The main way I have a different freedom is that as my general chops slowly but ongoingly improve, I get better. Slowly.

Beyond all the individual tracks, what do you hope people really take away from ‘Song Shards’ as a whole? If this album is a snapshot of Peter Stampfel right now, both as an artist and just as a guy, what do you think it shows us?

Whoo! Hmm! 1/ A number of the stoic aphorisms have truly helped me be, um, a little wiser? A little kinder? A little less resentful? As I said in the liner notes, I think many of them could provide children with life-useful information. Adults too, of course. 2/ If more songwriters wrote more short songs, this would not be a bad thing. 3/ Encourage appreciation for commercial jingles, and hopefully inspire a worldwide archival movement. Definitely a me-now snapshot, and I’m deeply grateful to Mark Bingham and Jalopy Records for allowing me to dump it onto the public’s lap. 4/ Encourage people to consider prayer as a possibly useful activity. 5/ Take the Dunbar Number section to heart. Admittedly, it might be a crackpot concept, but there are some good ideas there. Like kick ALL toxic people the fuck out of your circle of acquaintances. Now, dammit!

Holy Modal Rounders… legendary for taking those old folk tunes and just totally flipping ’em, right? Like, not just playing ’em, but really messing with them in a way that probably made the serious folkies clutch their pearls. Can you think of one specific old song, maybe something from an old record you dug up, where you and Steve Weber just looked at each other and thought, “Okay, how can we really twist this one inside out to make it sound like us?” What was the crazy idea you had for it, how did it all shake out when you played it, and what was the wildest reaction you ever got from someone who heard your totally warped version back in the day?

We were never that deliberate about it. Most of our early stuff was actually done pretty straight. The main change tended to be to the lyrics. I’ve been misquoted as saying I didn’t look up the words because I was too lazy. What really happened was that some words were hard to make out on those old 78’s, so I would take my best guess. Invariably, when I would discover the “right” words, I would think, hell, mine are better. Of course, we would tend to feature sex and drugs, because sex and drugs.

The strongest reaction I’ve ever had was pre-Rounder, back in 1960. I was playing with my original NYC group, MacGrundy’s Old-Timey Wool Thumpers. We were playing in a park and a bunch of nicely dressed Catholic high school kids started listening to us. They kept asking us to play ‘Tom Dooley.’ We had just learned a much cooler version by the New Lost City Ramblers, and played that. The kids went berserk—we were doing it wrong!—and attacked us. George Dawson, our banjo player, had always wanted to slug somebody with his banjo, and did so. I grabbed my fiddle and ran. A girl who was with us ran up to me and said, “Come back! They’re beating up Ben!” (Rifkin, older brother to the eventually better-known Josh Rifkin). She grabbed my arm and pulled me back to the melee. Ben’s face was bleeding, but the lads’ bloodlust had been sated, and they all milled around looking guilty. We went back to the Village, and were telling some friends what happened. A Village Voice writer happened to be there, and he started taking notes. But when he found this happened in an uptown park, not in the Village, he told us the story was not newsworthy.

Alright Peter, let’s say we’re just hanging out and you’re about to put on some records for me right now, today in 2026. What’s one or two albums you’d definitely spin to show me something cool or important to you these days? And then, just for fun, imagine we could zap back to 1966 – what records would you be putting on the turntable for me then?

If I was going to play someone an album I had, it would be the 100-song multi-album ‘Excavated Shellac’ on Archephone, sort of a world music Harry Smith Anthology collection. But I’d be more likely to turn on Radio Garden on my computer—you know about that, right? Instant access to thousands of radio stations worldwide, all free. For years, my go-to stations were three in Madagascar, which Henry Kaiser told me was the farthest reach of the Pacific Islands diaspora. Amazing shit. I also love stations from Africa and India. And I had to check out North Korea, mainly big choruses/orchestras.

Wow, 1966. I’d play the Yardbirds ‘Over, Under, Sideways, Down,’ Stones ‘Aftermath,’ Beatles ‘Revolver,’ Kinks ‘Sunny Afternoon,’ Who’s ‘Happy Jack,’ Beach Boys ‘Pet Sounds,’ Incredible String Band’s first album, the Joseph Spence Elektra album, but would mainly play the radio-pop stations and R&B stations. Our fave station was WKBW in Buffalo, which only came in at night.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Peter Stampfel (photo by Brian Geltner)

Peter Stampfel Website