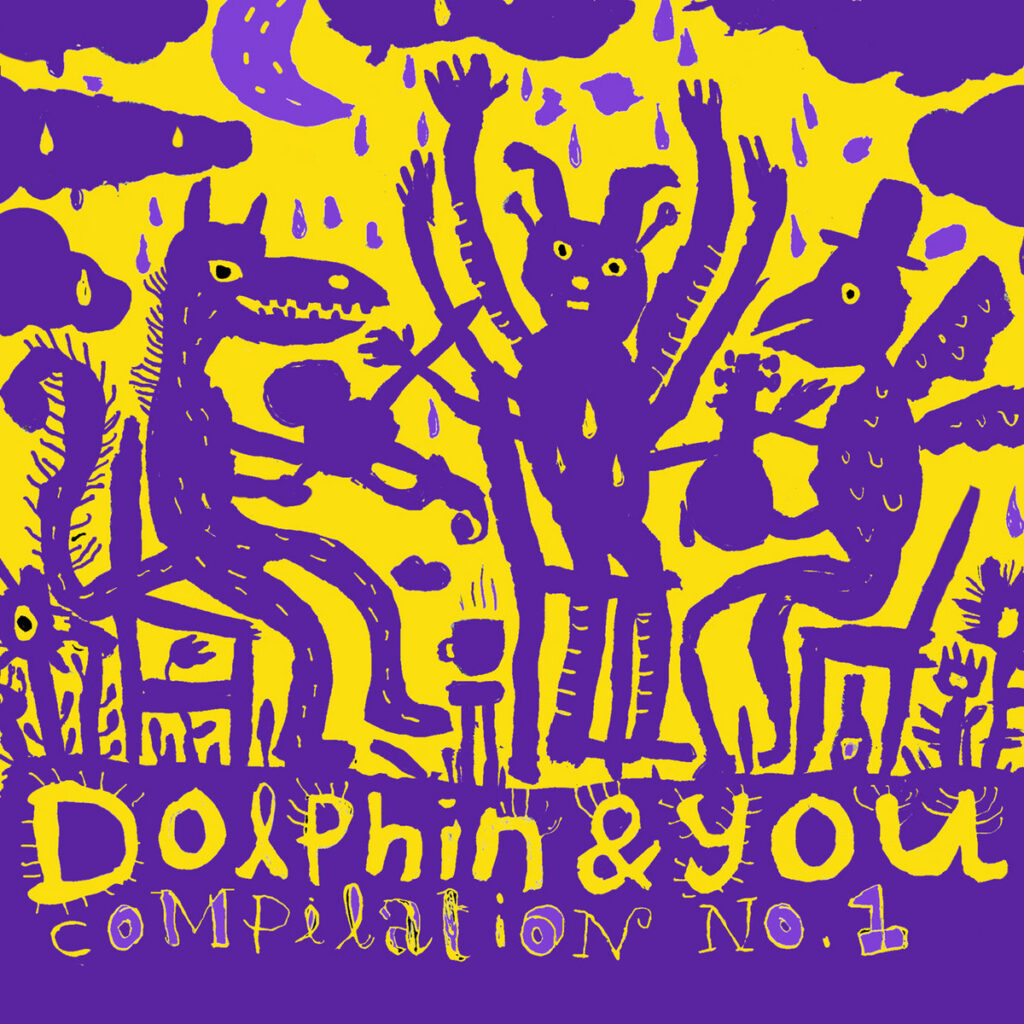

An Ecosystem of Sound: Brian Dolphin’s ‘Dolphin & You Compilation No. 1’

Brian Dolphin, a Manhattan native with harmonies inherited from rural folk and adventurous 80s and 90s albums, has spent a lifetime seeking the transcendent moment where individual voices dissolve into one colossal, beautiful sound.

His passage, informed by early forays in New York’s cacophonous anti-folk scene and sharpened by academic dives into ethnomusicology, culminates in the magnificent double album, ‘Dolphin & You Compilation No. 1.’ What we have here is a sonic ecosystem, a chronicle of radical collaboration created across marathon recording sessions. Fifty musicians, spanning a kaleidoscope of intimacy and style, converge here, each track something else. Dolphin acts as the gravitational center, pulling together disparate energies…from a tightly arranged, harmony-rich original on the ‘Dolphin’ side to the communal spirit of the ‘You’ side, often recorded live in a single, utopian breath.

The magic lives in the unplanned. It’s in a forgotten jam session suddenly outshining weeks of rehearsal, or the unexpected perfection of a string arrangement sent from afar. Dolphin’s method honors the heart’s instinct: choosing a song because a collaborator’s “soulful, vulnerable, truthful energy” demands it be heard. The resulting compilation is a red thread of human connection, a profound argument for why we must stop looking at screens and simply sing together.

“There’s something really cosmic about everyone singing the same words and vibrations together and experiencing that oneness.”

It’s an absolute pleasure to have you here. To kick things off, could you share a bit about your background? Where did you grow up, and how did you first find yourself drawn into the world of music?

Brian Dolphin: I’m a Manhattan boy. There are some musicians in my family; my father carries a flute around him at all times, my uncle is a jazz pianist, and my aunt is a classical singer and songwriter. So there was live music around the house growing up, but maybe even somehow cooler than that is that my parents listened to a lot of great music while I was growing up—a lot of world music from Georgia and the Balkans, new age music, Peter Gabriel, Enya… some beautiful things that were really enchanting in my childhood and put harmonies in me that I would be searching for all these years later and ever after. Also, my friends growing up were really into music, so we made little bands, kind of the same thing I’m still doing. Lastly, New York is a loud and vibrant place, so there’s just always noise and music coming out at your ears at all hours, and I find that this kind of chaos helped me make sound to kind of harmonize with it.

Back in your younger days, were you part of any indie scenes or underground circles? Do you have any memories of a gig or a moment that really sparked something in you?

I think the anti-folk scene around Sidewalk Café and the Catweazle club at Tribes Gallery around the 2010s was really cool. I mean, I’ve been writing songs since I was like 12, but it was good for me to try and write a new song every week and show it to them and get inspired by how good so many people were. Nothing like trying to impress your friends. I used to record the Catweazle club for ten dollars every week for their blog, and I was living off of like nothing at my mom’s house, so that took me on the subway a few times and bought me one-dollar pizza slices. There were a couple moments when someone would have a really catchy, triumphant chorus and everyone would sing along, and this dude Brer would play trumpet and Cal would jump on piano on people’s songs. So this scene itself could have crazy, energetic, collective utopian moments that were deeply beautiful and transcendent of self. That’s my North Star.

You’ve got this fascinating background in ethnomusicology and community singing. How have those experiences shaped the freewheeling, collaborative spirit we hear so vividly in Dolphin & You?

Well, the community singing thing was always about getting to that state of merging everyone’s voices and consciousness together to become the one thing. And with ethnomusicology, that really was first my amateur and then my professional research delving into music to understand the deeper ways that people use it to engage with each other and the natural world. Though I mentioned the world music and harmonies I was into very young, I also got a big grant to study “The Music of Nature and the Nature of Music” when I was 22 years old, and I traveled all around the world and learned and played music with people and understood how people could herd reindeer with music, how it could heal, how it could help people understand themselves and their own unique niche in the cosmos. It’s like I grew up knowing there was something deep in music, and I’ve just progressively tried to explore and explode what that is. One of the ways is through research, and the other is through getting a bunch of people together and both trying stuff out and working on each other’s music to help it along.

Let’s move on to your latest adventure, the ‘Dolphin & You Compilation No.1.’ What was the original spark behind this project? What idea set you on this path?

Basically, during my ethnomusicology grad school years in New York City, I was finding it hard to both have the time and to find people that had the time to have a stable band. And yet I was still writing a bunch of songs, and I knew a bunch of songwriters in New York, so I thought, hey, let’s just get a bunch of songwriters and musicians together, and we’ll play together and learn each other’s songs, and then maybe we could record it. I had already been in bands where we all did each other’s songs, so why not open it up to more people and also make it slightly less committal. So I posted on Facebook and said whoever wants to be in a band, we’ll do my song and your songs, and we’ll practice every Monday, and eventually we’ll record an album. And like two months later, we did spend a whole day recording that album, but you know, people were absent or late for different rehearsals, so we had to keep re-teaching and re-arranging the songs, and in the end I was like, yo, we could have just spent one day together rather than weeks and recorded two or three or more of the songs that way, and they would have been just as good. So I moved onto that paradigm. That first band that started this idea, though, was very cool, and there’s something to be said about spending more time with the people you’re making music with that definitely can give it more depth.

These marathon six-hour sessions are insane! Can you recall some of the most memorable or unexpected moments that have come out of those intense, creative marathons?

Two moments.

One: after this very first band spent all day recording each other’s songs that we had spent months learning, we just started jamming and making stuff up on the fly, and it might have been better than anything else we had done. It was like all the time together and learning songs and practicing might have just been rehearsal for a very exploratory jam where everyone had their own voice and knew each other’s voices too. I honestly haven’t captured nearly enough of that raw, unplanned, improvisatory collaborative spirit with this specific project, and I would like to.

Two: in late February of 2020, I tried to record a six-hour album in Sandy Mush, North Carolina, and the music was very good (and Saro Lynch-Thomason’s track was from this session), but we had brought our baby, and our other friends also brought their baby, and it was a little crazy. Sometimes they would strap their baby on and play fiddle—there’s a picture of that in the press kit. Elizabeth definitely sang while holding our kid. And sometimes they would be in the other room napping or playing with someone there. Anyway, it was very chaotic but very much a family affair, and miraculously I was able to painstakingly edit out any extra baby crying sounds from those recordings.

“I think I have a specific kind of indie, weird, sometimes lo-fi, intimate, voice-centered, moody, harmony-loving aesthetic that I filter”

With over fifty musicians contributing and such a kaleidoscope of styles, how do you manage to keep the whole project feeling so cohesive?

I think I have a specific kind of indie, weird, sometimes lo-fi, intimate, voice-centered, moody, harmony-loving aesthetic that I filter a lot of things through, and so I just picked a bunch of my favorite tracks and ones I thought would touch people and combined them into this double album. I put it on two CDs: one of my own songs and one of all of these collaborations, also because they felt different. Whereas my songs—the ‘Dolphin’ side—were more collaborative before the pandemic, at some point I did start just going deep into my own studio work and finishing all the songs with just me singing, playing, recording, arranging, and mixing the parts. So the through line there is my own voice, songwriting, and musical sound even while the songs were recorded in different houses and with different production.

I think the ‘You’ side in some regard feels more cohesive in spite of all of the genre shifts because the vast majority of those songs were recorded live by a bunch of people hanging out in a room together, sometimes doing one of those six, eight, ten-hour marathon sessions. There’s the sound of the room and the communal there. And yes, that live feel I like a lot; on some songs there’s still that feeling of the community sing or the singer-songwriter’s club because you can feel how intimate and connected those people in the room are. That’s the red thread in all of this.

There must be a delicate dance between spontaneity and planning in these sessions. How do you decide which impromptu moments or songs make the final cut?

Honestly, I just invite people whose songs I like. Most people send me demos at this point, and sometimes I even steer people a certain direction because I start to imagine how the arrangement would go or I think the melody is particularly strong. Often enough, though, regardless of my own inclinations as to their song choice, you can tell that a songwriter has strong feelings about a particular song, often their little intimate baby song. It’s really funny and cute sometimes even how they try and hide it and say things like, “Oh, this one is not fully done yet, and it’s kind of dark, but I think it’s really special, but I don’t know.” So in these cases I ask them if they want to do it, and they make puppy dog eyes and admit that they would really love to do a particular song. And because that’s where their soulful, vulnerable, truthful energy is, it really brings something special to the room that we all get to serve, respect, and honor. And because ‘Dolphin & You’ also serves to get people’s songs “out there” and heard, it’s nice to get the songs out of people that they really care about—songs that really feel like them, songs that might need just a little coaxing out of their shell to show you who they are in all their colour and splendor.

The whole idea of community and shared creativity really stands out. What does it mean to you, personally, when you see a room full of strangers transform into friends through the act of making music together?

I mean, it’s kind of the best. If people spent more time singing together and sharing culture like that instead of being isolated and looking at screens, we’d all feel much better and be more connected with each other and just happier and more self-expressed too. There are a lot of singing organizations that exist because people know that singing together—and there are even a bunch of scientific studies on it now—makes people happier. And you know, I do it a fair bit, but still it’s not enough. I do find it hard to make the time, but when I do it’s always worth it and more. There’s something really cosmic about everyone singing the same words and vibrations together and experiencing that oneness. It’s like a completely natural and sometimes almost banal high.

I’d love to delve a little deeper into the tracks themselves. Can you shed some light on a few of the pieces featured on this compilation and what they represent for you?

There are a few tracks on this album that were actually from the same session. When the pandemic hit and we were in lockdown and I wasn’t getting together with people in person to record stuff anymore, I started something I called a “songwheel,” where five of us would record our own song and then pass it off to the next person to record overdubs on it. Ultimately, it took a lot of work to coordinate us musicians being musicians; people took a while to get their stems back to me, and it was unwieldy in that regard, but the music that people made was very dope.

“And We Go to School” was one of these songs, and I remember recording the guitar and vocal and sending it out to these friends, and then feeling like I was slowly getting a bunch of holiday gifts back in my inbox. Like I heard the drums that Eric Farber laid down, and I was like, hmm… okay, a little different than I imagined, but then… wow, that’s way better than I imagined… oh yes, that slaps—that’s the way. The same thing happened with Suzy Jivotovski’s track, ‘Alive,’ which is the first track on the “You” side of the album, where I got back Bach Bui’s fiddle and cello tracks, and I was completely floored. I didn’t even know that Bach played cello, and here he was arranging and recording perfectly executed, vibey, beautiful string arrangements. Those are my favorite string arrangements on the album. Again, they are so moody and transcendent and so deeply musical.

How has this approach influenced the way you write or arrange songs, especially compared to traditional studio methods?

As time goes on, I think I have learned to let go a bit more and trust the people in the room more rather than bringing in my perfectly arranged songs with all the vocal harmonies written. I could do that myself, and I do. So I look now at these collective sessions as ways to open up my own ear and start to hear what other people might hear, and new aesthetics and even genres of music can manifest and develop that way.

Do you have a story where the collective energy of the group unexpectedly transformed a song, taking it in a direction you hadn’t imagined?

‘Swim in the Moonlight’ was a song where everything just kind of lined up. Some of us in the room had already played together on each other’s songs or played Old Time or Irish fiddle tunes, so there was already a bit of a developed musical language there, but we hadn’t all played together. But yes, we all kind of listened very well and found musical melodies and harmonies that interlocked with each other, and we filled in the corners with little musical responses. So yes, the song went from a very solitary banjo and vocal piece to something that really feels like a bunch of friends really relating to each other musically and having a good time of it. It’s very fitting that the song itself is about a bunch of friends going off and swimming together in the moonlight.

Looking back, the project has grown from those intimate monthly ‘Community Sings’ in Brooklyn to this sprawling 31-track double album. What has been the most rewarding part of watching it evolve over time?

It’s been beautiful to just keep things evolving and to try and be very honest with what my needs are as a music-maker and try and tailor things to that. Like the community sing was good but hard to organize, and the six-hour albums are good, but sometimes I need more time with the tracks and the people, so now I’m thinking of ways to get musicians for longer amounts of time, like in residencies.

Now that this compilation is out in the world, how do you see the future of Dolphin & You? Are there more experiments in store, or new ways to unite people through music on the horizon?

Yes, I think residencies will be good. I think some touring will be good. More live performance too.

Your earlier work, spanning from traditional folk to some really experimental soundscapes, when you’re curating a project as varied as Dolphin & You, how do you decide which elements to carry forward or let evolve?

That’s a good question. That’s a question of curation. And it’s just a matter of taste and what hits me emotionally. Like I don’t listen to a lot of metal, but Milkmother’s song was just so brutally real and felt that I thought it would fit well and diversify the album, which itself does have a lot of mellow and slow songs. I guess I had to Marie Kondo the songs and see which ones I had strong emotional attachment to and which ones I could let continue to have their own solitary existence.

Your Bandcamp catalog really reads like a living diary of your artistic journey. Could you share some further words about it?

Basically, I’ve just been doing the same thing forever. My first album was recorded on a little tape machine in my closet when I was 13 years old with my friend Andre. It was my songs, it was his songs, it was us playing on each other’s songs. Dolphin & You? Almost all of the music on my Bandcamp is just the same—it’s playing on other people’s songs and them playing on mine. That’s the sweat equity of it all right there. I do enjoy having my own band, but that is more of a stretch and less of a natural fit for me and how I understood music-making from the beginning.

Looking ahead, what future plans are you excited about? What’s next on your musical journey?

I’m still doing six- and eight-hour albums, and they are great, and I’m meeting all sorts of people through this process still, but I’m also getting more into doing live music again and going analog. So yes, I think some collective performances might be on the horizon, where perhaps we perform the songs that we have already recorded together. Also, while the marathon recording sessions are nice, effective, and fun, I am enjoying spending more time with people, so we are starting to plan some residencies where we record more tracks and have a bit more creative freedom over, say, a weekend. I think that will allow more collaborative and musical freedom too. Also, yes, the pandemic is over, so I’m playing out a lot more, playing fiddle and klezmer and my own songs and directing Philly Folk Choir. It’s pretty busy actually.

And before we wrap up, let’s talk favorites. What are some of the albums that have been resonating with you lately? Anything new that you’d recommend to our listeners?

I really like the Marie, The Band song ‘Night Driving.’ I think they’re very charming and real at the same time, which is really hard to do. Also, the Out of Sight of Land track ‘Cloudheart Music Pt.1’ is really amazing at bringing me right back to 2019. There were like nine of us in the room recording and singing and beating drums and xylophones and playing fiddle and melodica, just really feeling the communal atmosphere of our ad hoc band. I really feel like the song captures that feeling. This was also pre-pandemic, so we were very close to each other and breathing each other’s air and sweat. It was also for me pre-marriage and pre-child, so it has feelings of freedom and individuality wrapped into it.

Klemen Breznikar

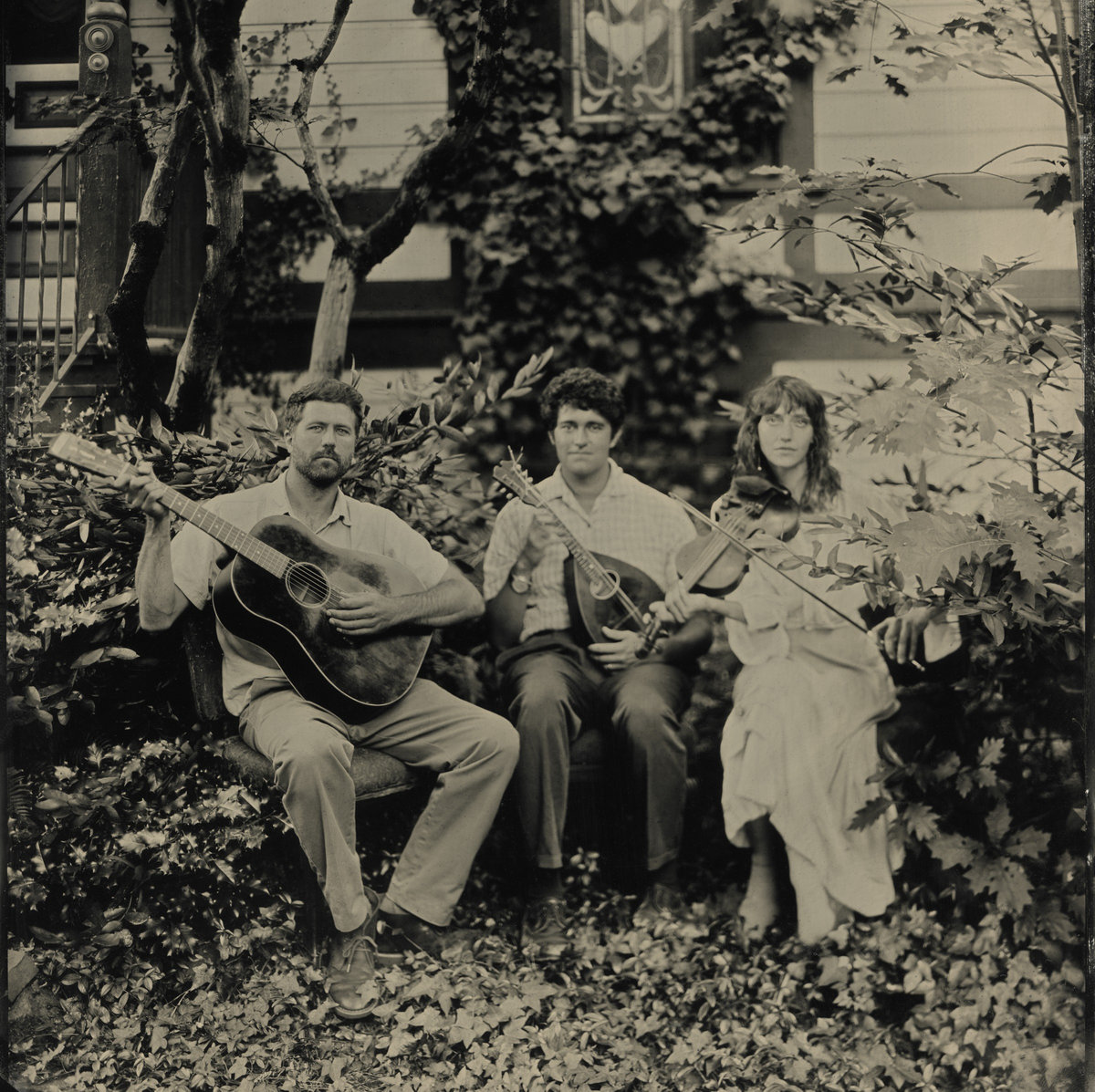

Headline photo: Brian Dolphin (Credit: Willem Cousineau)

Brian Dolphin Website / Facebook / Instagram / YouTube / Bandcamp