Stereocilia’s Journey Through ‘Phases’

Amid the deepening thickets of ambient minimalism and experimental drone, few voices have remained as defiantly personal and unfalteringly consistent as that of John Scott, the Bristol-based composer operating under the Stereocilia moniker.

What began as an improvisational excursion over a decade ago has evolved into a meticulous practice that balances instinctive textural layering with an architectural attention to structure, often resulting in compositions that unfold with a quiet inevitability. His recent work, ‘Phases,’ reveals an artist equally at home sculpting sprawling synth contours as he is grounding melodic fragments in the tactile grain of guitar loops recorded onto phones during countryside walks.

Scott’s approach to sound feels less like composing in the traditional sense and more akin to mapping a landscape through resonance, using both analog and digital tools not to obscure the source but to amplify its emotive potential. There is no reliance on imposed conceptual frameworks; rather, what emerges is the result of prolonged interaction with sonic material itself. Informed by past collaborations with guitar orchestras and a deep affinity for minimalist lineage, Scott has developed a language where repetition becomes meditation, and nuance exists not in gesture but in accumulation. Stereocilia’s music does not demand attention. It rewards immersion.

“It’s all about the sound.”

Your music always feels like it’s building something massive, like layering sound blocks until it forms this towering structure. When you start a track, do you have a clear shape in mind, or is it more like following the sound and seeing where it takes you?

John Scott: When I started Stereocilia in 2012, it was all improvisation. I would go on these journeys and, over time, I would grab snippets from the improvisations and build on them. That’s how I wrote the first two albums. Then in 2017, I was able to set up a studio at a place called The Island in Bristol, which is an old police station that is now a creative hub right in the centre of Bristol, with artists and musicians.

Now I have the studio, whenever I am improvising, I can just hit record and go from there. Songs are more structured from the offset now. I don’t have any music equipment apart from an acoustic guitar at home. That is where I come up with riffs a lot of the time. I record onto my phone so I don’t forget them. I will take those riffs into the studio and try to figure out a song around them.

A lot of people describe your music in cinematic terms: big, atmospheric, almost like it’s scoring some unseen film. When you’re working on something, do you ever have visuals in your head, or is it all about the sound itself?

It’s all about the sound. I never have any visuals in mind when creating music. I think because a lot of my music is long-form, it lends itself to something of a journey, which is probably where the comparisons to film scores come in. I have done a live score to a film in the past, the 1927 film The Fall of the Romanov Dynasty for the Bristol Radical Film Festival. I would love to do another one someday.

You’ve played in Rhys Chatham’s guitar orchestras, which must have been wild… so many layers of sound vibrating together. Did those experiences change how you think about repetition and texture in your own music?

The first time I played in one of Rhys Chatham’s guitar orchestras was at Liverpool Cathedral in 2012. That gig changed me… the way I feel about music, the way I perform music, and the way I see myself. At the time, my dad was terminally ill with cancer. I was going through one of the toughest periods of my life, but at the same time, I was being immersed in one of the most inspirational things I’ve ever done. It was a real rollercoaster.

I’ll never forget how incredible it sounded in that cathedral that night, how 100 guitars can sound like a full orchestra was incredible. It had such an effect on how I thought about music. I did two more of Rhys’ guitar orchestras, one in San Francisco and one in Birmingham. At each of these events, I made friends along the way who I’m still in touch with now. I think one of the most important things I took away from those experiences was how music brings people together and how it can create lasting relationships. That truly is the greatest thing.

Your live sets have this hypnotic, immersive quality, and it’s really easy to get lost in them. How much of that is planned, and how much of it is about reacting in the moment?

There are still elements of improvisation within my live shows. I’m doing things on the fly that are not necessarily on the album. I also can’t do everything that I do in the studio live, so songs take on a different structure and meaning when performed live, which creates something new for me and the listener.

You use a mix of guitar, synths, and looping to create these dense, evolving soundscapes. Have you ever stumbled upon a sound that just stopped you in your tracks, like, “Whoa, where did THAT come from?”

All the time. Especially as I run my guitar through Ableton, it opens up a whole new world of effects. I’ve had to get pretty good at note-taking to remember all my settings, especially if I’m taking that song into a live setting.

You’ve shared the stage with some serious heavyweights: Ben Frost, William Basinski, Acid Mothers Temple. Any particularly memorable moments from those shows that left a lasting impression?

I’ve been fortunate enough to share a stage with many amazing artists that have inspired me over the years, and the ones you mentioned were some of my favourites. I’ve supported Acid Mothers Temple three times over the years, the last being in Berlin in 2019. I remember the second time I supported them in York in 2015. It was the hottest gig I’ve ever played in my life. Condensation dripped from the walls and ceiling. It was crazy hot in there. I could barely hold on to the neck of my guitar because the whole venue was like a sauna.

I supported Daniel Lanois in Bristol years ago. He was super sweet. He let me drink his beer rider, but I was under strict instructions not to touch his whisky. I behaved, even though it was a cracking bottle of whisky.

There’s something very spatial about your records… it’s like they create their own environment. Do you think about space when you’re making music? Not just the literal space, like a room or venue, but also the way sound moves and shifts over time?

Again, it’s not a conscious decision when I go into the recording process. It kind of just comes naturally. It takes time to get an album in the right running order, especially as I like an album to flow naturally.

“I think my music is more rooted in nature.”

Even though your setup includes a lot of electronic elements, your music still feels really organic, almost alive. Do you see your sound as more rooted in nature, or are you more interested in exploring something beyond that, something otherworldly?

I think my music is more rooted in nature. I go out walking a lot. We head over to Wales fairly often to walk in the Wye Valley. I get a lot out of that. I’ve never really been into sci-fi, but I can see how you could interpret some of my music to be inspired by that.

A lot of your tracks evolve in these long, slow arcs, where melodies and textures shift in subtle ways over time. Do you think about time in a linear way when you play, or is it more like existing in a loop, stretching and bending as you go?

I think it stems back to improvising, setting up a loop and seeing where it takes me. I don’t make a conscious decision to write a 20-minute song. It just ends up that way. When I play live, I always finish with ‘Celestial Light’ off my 2019 album ‘A Silence That Follows.’ I get lost in that song myself when I’m playing it. I find it very meditative. People always come up to me after I’ve played and say they got lost in my set. I love it when that happens.

Could you share some further words about your latest album? How do you see it in your discography?

I’m really pleased with how ‘Phases’ turned out. It sounds corny and everyone says it, but I really do think it’s my best album. It really is an album of two halves. On Side A, I really explore my electronic side, and I love the change in tempo on Side B. More traditional instrumentation, but still with that electronic undercurrent running through it.

I’ve had so much positive feedback about it too, which is lovely. It’s the first time I’ve done an album on my own since 2016, and I did everything on it this time apart from the mastering, which was done by Chuck Johnson, who did an incredible job on it. The bass on the vinyl sounds fantastic.

I’ve managed to pull off five of the songs live as well, which I’m super pleased with. It was tricky doing ‘Trust’ live without a drummer, but I’ve programmed my drum machine and it’s turned into a whole new song, which I love playing just as much as the album version.

You’ve done music for film, including The Boy With the 8-Hour Heart. How does scoring for a visual piece compare to making your own albums? Do you like the challenge of working within a set mood or narrative, or do you prefer the total freedom of solo work?

I love the challenges that doing a film score brings. You really have to think outside the box, which spurs creativity. I worked a lot with the Tate Modern in the past, working on their short documentary series on upcoming artists. There was more free rein for those than for long-form documentary scoring.

I’ve worked with director Nick Aldridge in the past, so he knew what angle I would come at for The Boy With the 8-Hour Heart. He would make suggestions of themes and instrumentation, but I pretty much had free rein to do what I wanted on that. I’m super proud of how that film came out. It was a heartfelt story told really well, and I feel that the music added to the story without overbearing it. I highly recommend checking out Nick’s other work, including the BBC Storyville Hillsong Church: God Goes Viral.

“I’ve always been a fan of repetition.”

Your music reminds me of early minimalists. Deeply immersive, built on these hypnotic cycles. Do you feel any connection to that tradition, or do you come at it from a totally different angle?

I’ve always been a fan of repetition. I love being hypnotised by sound, and that’s something that certainly comes across in my work, especially live. I like to draw the listener in. I went down a rabbit hole of listening to minimalist composers in my late 20s. There’s a meditative quality to listening to minimalist music.

I love the history of the New York scene and everything that stemmed from it. I’ve been lucky enough to go to New York four times over the years. I managed to go to La Monte Young’s ‘Dream House’ back in 2021. It’s basically an ongoing sound installation that’s been running nonstop since the 90s. A simple setup of speakers in a room, playing sine waves. It’s incredibly hypnotic being in there, and then you move and the tones change depending on where you are in the room. Such a simple concept, but it has so much going on. So yes, I would definitely say I’m influenced by them.

From a more modern take on it, I remember watching Oneida in the early 2000s playing ‘Sheets of Easter’ for 30 minutes and being totally blown away by it, simple repetition. You can’t beat it.

And it’s also full of these tiny details, things that might not hit on first listen but reveal themselves the deeper you go. Do you deliberately try to pull people into that level of detail, or is that just a natural part of how you build sound?

I think that just comes naturally. Lots of subtle effects going on in the background that you might not notice the first time around. On my latest single ‘Trust,’ I ran the whole mix through a reel-to-reel tape recorder and fed it back on itself dub-style, just to see what it would sound like. I ended up loving it and having it buried in the mix. You might not notice it at first, but the guitar solo is panning hard and going mad under the main mix. I don’t always notice it myself, but when you hear it, it really adds to it.

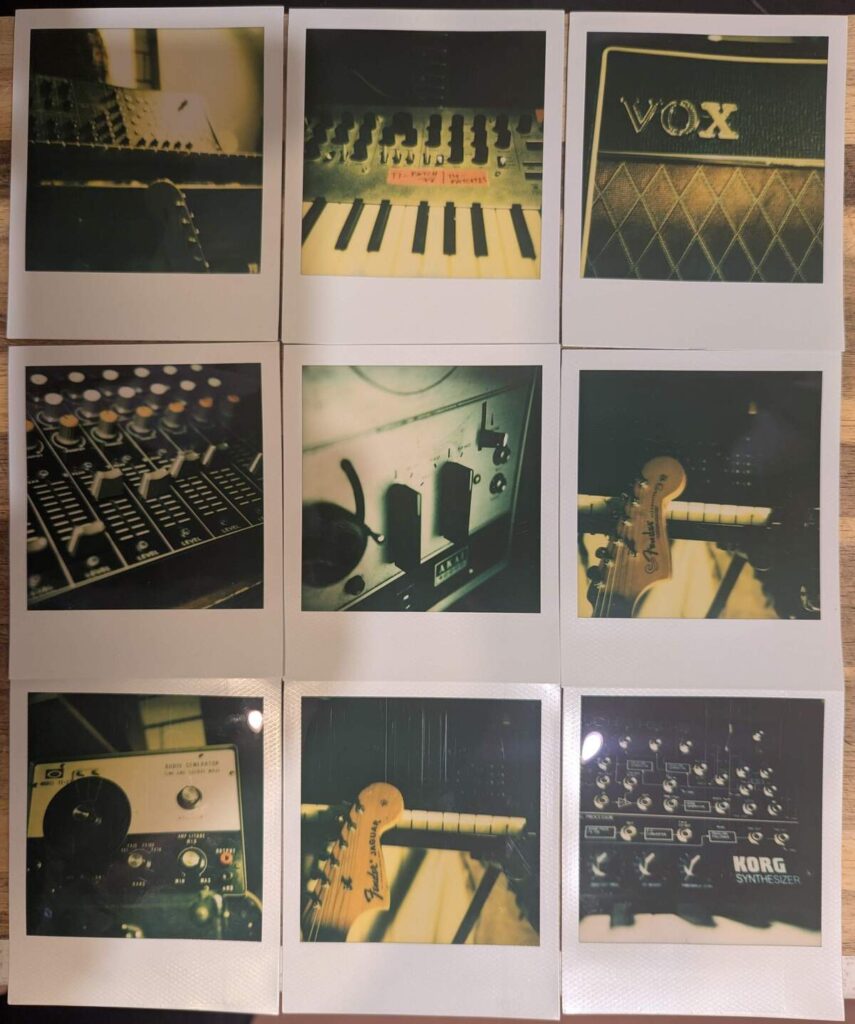

For gearheads, could you elaborate on the instruments, effects, etc. you’re currently using?

I don’t use as many pedals as people probably think. I’ve really fine-tuned my pedalboard as the years have gone by. I think I only use five or six these days. The Eventide H9 pedal is doing the bulk of my textural work, and you can’t beat a ProCo Rat for some filthy distortion. When I play live, my guitar signal is split into Ableton, where I’m running additional effects that I control with a MIDI controller.

In the studio, I used a Korg MS-20A, Korg Minilogue, Moog Minitaur and a DrumBrute for my drum machine. My main guitar is a Fender Jaguar that I’ve had since I was 18. I don’t really play it live anymore, as I’ve switched to a Squier Supersonic, which I absolutely love. It’s super light and great for touring… saves my 40-plus-year-old back.

You’ve worked with some great indie labels: Drone Rock Records, Low Point, Echoic Memory. What draws you to those labels, and how do you see their role in keeping experimental music alive in a world that’s so focused on quick-hit streaming?

Working with small independent labels is all I’ve ever wanted to do. The people that run these labels are the lifeblood of independent music. We need that passion in an ever-changing landscape. I’m not interested in how many streams I have on streaming services. I would rather someone stream my album on Bandcamp. Maybe they might like it enough to buy a vinyl, CD or download.

Maybe it’s my age, but I’m a more visceral person, and I’d rather like something enough to purchase a physical item from the artist. Obviously, streaming services are here to stay, but I’d rather sit down and put a record on than skip around not listening to a full album the way the artist intended it to be heard.

What currently occupies your life, and what’s next for you?

In February and March, I went on two short tours, one in the UK and one in Europe. It was fun to be back on the road again. I’ve not done any long tours since 2019. Short bursts are the way forward for me, especially juggling a full-time job.

I’ve just come back from a trip of a lifetime to Japan and South Korea. I was fortunate to play some gigs whilst in Japan. I met and played with some brilliant acts, including a show with Tabata Mitsuru, who used to play bass in Acid Mothers Temple. We did an improv set at the end with saxophonist Kazuya Wakabayashi. It was wild. Travelling around Japan was really inspiring. I have lots of field recordings that I’d like to do something with at some point.

I’m also planning some more shows for the end of the year and hoping to start the follow-up to ‘Phases’ in the not-too-distant future.

Oh, and tell me what’s on your turntable as we speak?

I’m also a live sound engineer, and I’ve got to work with some great people over the years. Last year I was fortunate enough to be a sound engineer for Seefeel. Their latest release ‘Everything Squared’ is absolutely amazing, one of my favourite things that they’ve done. Another great band I did engineering for last year was Earthball. Their album ‘It’s Yours’ is a cracker.

I recently just finished Steve Turner from Mudhoney’s autobiography, and that sent me down a Mudhoney rabbit hole, which I haven’t been down in a long time. It’s been good reacquainting myself with their entire back catalogue. ‘Piece of Cake’ is still my favourite album, despite what Steve Turner says about it. It’s the one that got me into Mudhoney, and it will always have a special place in my heart.

I bought a load of records in Japan, and I’m currently working my way through those. Grabbed a couple of Mong Tong records I was missing. I also got some great recommendations of Japanese 60s and 70s psych, which I’ve been digging too.

Klemen Breznikar

Stereocilia Website / Facebook / Instagram / Bandcamp