Jim Cregan | From Blossom Toes, Family, Steve Harley & Cockney Rebel to Rod Stewart | Interview | New Album by Cregan & Co.

Jim Cregan is a British rock guitarist and bassist best known for his work with legendary groups such as Blossom Toes, Family, Steve Harley & Cockney Rebel and Rod Stewart.

Jim Cregan’s early work with Blossom Toes, Family, Linda Lewis, Cat Stevens and Cockney Rebel eventually led him to join the new band started by Rod Stewart, after the break-up of The Faces. He stayed for 18 years as his band-leader, co-writer and co-producer. Together they wrote such songs as ‘Tonight I’m Yours,’ ‘Forever Young,’ ‘Passion’ and most recently ‘Brighton Beach’ from Rod Stewart’s legendary album ‘Time’. Cregan is still making music with his band Cregan & Co. and they recently released a fantastic album ‘Spreading Rumours’.

“I have been writing with some of the finest lyricist in the world “

It’s great to have you, would you like to talk about your latest album, ‘Spreading Rumours’ by Cregan & Co.?

Jim Cregan: The album consists of mainly new material and some of it is written by Sam Tanner and myself. A couple of tunes were written with other guys, for example a song we had that was a hit with Joe Cocker [‘N’oubliez jamais’], is written by Russ Kunkel and myself and there’s a few written with Bernie Taupin, ‘Start Cryin’,’ it’s something we wrote sometime back and another song called ‘Shayne,’ which was originally supposed to be for Roy Orbison, but Orbison sadly passed away before I was able to send to him. We also have a few singles out, ‘Spreading Rumours,’ the title track, ‘Best Of The Bad Boys,’ both of these tracks were written by Sam Tanner, our keyboard player and myself. We actually worked on the album on and off for a couple of years. I mean I had some of these songs lying around for a long time. The tracks were recorded live and then we would finish them at home. We all have studios at home. We do our parts separately and then put them all together and generally mix it. It’s that sort of idea. I think it turned out to be quite a good record. We obviously are happy with it, otherwise we wouldn’t put it out. I suppose that’s the easy part of the story.

I hope you don’t mind if we go back to the early days? Where and when did you grow up? Was music a big part of your family life? Did the local music scene influence you or inspire you to play music?

I grew up in Poole in Dorset essentially with my brother Morris, who inspired me to be interested in music. He was bringing home all sorts of jazz, classical records that made me interested. We didn’t have a big collection of music. We listened to the radio mostly. My uncle gave me a ukulele with one string on it [laughs]. This is one of the reasons I claim I’m more of a soloist than a chord guy, because obviously the very limited chord you could play with one string [laughs]. I was fascinated by picking up melodies, so I did for a while and then eventually I got a guitar and hadn’t put one down since. That was when I was 13 years old. There wasn’t really much of a local music scene for 13 years old boys, so I was just listening to records. Bill Haley had his first hit, when I was a young guy. Our idea of rock ‘n’ roll in this country was a guy called Cliff Richard & The Shadows. They were a very influential instrumental band. At school I started a band playing Shadows covers. And also Duane Eddy, The Ventures and bands like that. Those bands helped us to have a repertoire, because I hadn’t started writing at that point.

Was there a certain moment when you knew you wanted to become a musician? Who were your major influences?

I guess it was sometime at school that I thought I might be able to get away with this. Maybe when I left high school and started college where I was going to Harrow School of Art and Harrow’s Technical College simultaneously which was fun, because I would tell people at the art school that I was at the technical college that day and vice-versa. I wasn’t really interested in school after a certain point, because as soon as I really became interested in guitar that was about it. I didn’t really care much about anything else. I wasn’t into sports, so… I guess I was about 17.

Tell us about the very early bands like The Falcons and The Disastisfied Blues Band?

The Falcons were my Shadows cover band at school, which was great fun. We used to play in the local youth club and every now and then we played at dance halls. We really didn’t make any money, but it was fun to do.

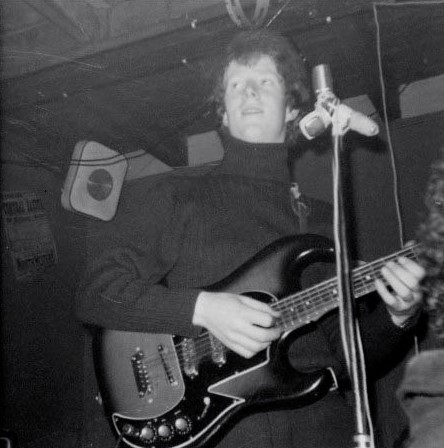

The Disastisfied Blues Band started at college. We had gigs and were making a bit of money. We would play at the Marquee Club opening for bands like The Yardbirds and Spencer Davis Group. They had Stevie Windwood on guitar. In those days he didn’t play Hammond. Then we also played with The Herd, which had Peter Frampton in it… so it was quite an interesting time musically. Eventually manager of The Yardbirds and one of the co-manager of the Marquee Club Giorgio Gomelsky thought I might be interested in a band that he had called The Ingoes and asked me if I would like to join, which I did and that went into Blossom Toes.

You also played with Dave Mason in Julian Covay and the Machine in 1967 and moved on to join The Ingoes.

Julian Covay was a man of many names. His other name was Philip Kinorra and he was quite a serious jazz drummer. He had some gigs at Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club, a premiere jazz club in Britain, maybe even in Europe, but he wanted to be a singer. He put this band together and somehow I found myself in, although I can’t really remember how I got the job. It was actually a really good band. They were all grown up R&B players and jazz and blues players. I was very much the new boy, I didn’t know what I was doing. Some of them were very kind and took me under their wing and showed me things that I would be playing, and stopped me being the square peg in a round hole. Dave Levy was the keyboard player and he kindly took me under his wing and led me back to his apartment in London and sat with me and showed me chords progressions and things that I still use now. He was a very nice player. I think it was probably self-preservation on their part as they couldn’t bear what I was choosing to play and thought I needed more education [laughs]. Despite the rumours Dave Mason and I were never in the band at the same time, but there’s a guy called Cliff Barton, who was the bass player. In those days he was considered to be the hottest bass player in town. He played with The Graham Bond Organisation, Cyril Davies and The R&B All Stars – you know, all the blues bands that you wanted to see in town. He was a great player.

What led you to name change into Blossom Toes?

At some point I joined The Ingoes as I explained before due to Giorgio Gomelsky’s invitation. I remember Giorgio sent us off to France as The Ingoes to hone our skills. The thing he liked about The Ingoes was Brian Godding’s songwriting. Brian already had a couple of records out with other people singing his songs. He’s a very good writer. He was hugely underrated and sadly never managed to get the hits he deserved. Giorgio just threw me into that mixture and I didn’t really realize that I could write some successful songs, which took me a little while to figure out how to do it, but eventually I figured out how to do it and was bloody lucky to be standing at the right place at the right time. That’s about how you get a hit [laughs]. We stayed in France working in clubs and made a very good reputation of themselves. We played as resident musicians in certain clubs. Boulevard de Clichy in Paris, in Toulouse there was a great club, we were there for a month. Eventually Giorgio thought we were ready and brought us back to England. We had to sadly change our drummer, because Colin Martin, a very lovely man, went on to become quite an important person in the BBC. He wasn’t quite up to speed for making albums, so we brought in Kevin Westlake who played with Little Richard and some other big names. He was a very good drummer, very good musician. He came in and Giorgio said we need a name change and some guy who was in Giorgio offices came up with a name. We all hated it, but Giorgio insisted that it’s the right name for a psychedelic band. When you consider Pink Floyd is kind of an odd name, we had an odd or even weirder name.

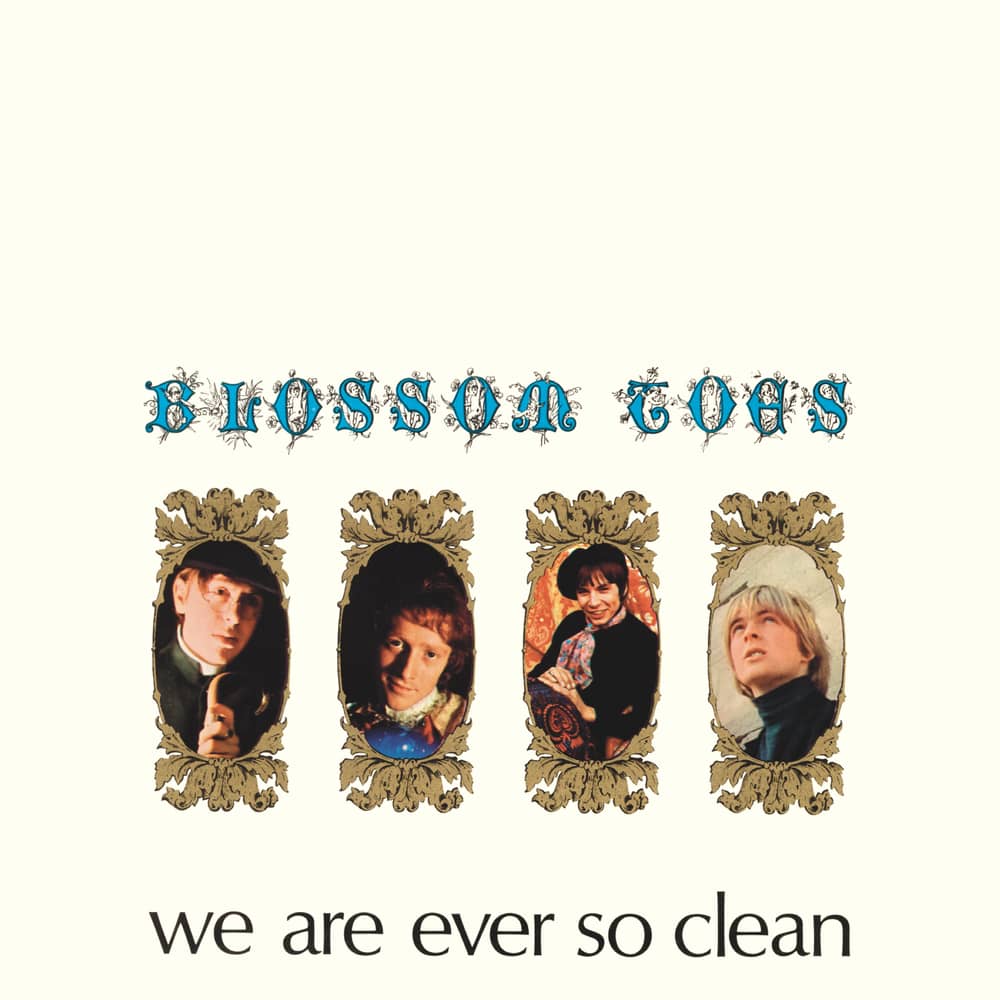

What are some of the recollections from working on your debut album, ‘We Are Ever So Clean’?

It was a very interesting record to me, because the band went to the studio and cut the tracks. Giorgio chose David Whittaker, who was an arranger to finish it. Giorgio was a bit of a string guy actually. He thought he knew what he was doing, which was not really true at all. Nobody really knows what they are doing. It’s just take your chances and follow your nose. Giorgio had a sizable nose, so he really had to follow it [laughs]. David Whittaker came in and helped some of the tunes and wrecked some of them. At some point he brought in a bunch of session players to play a couple of the tracks. I think Jimmy Page is on one of the tracks, and Allan White played drums on some of them. You know, they were really great players. They definitely had more skills than us at the time, but it didn’t make the album that much better. It just got done quicker. I think it was a bit overproduced.

By the time of your second album, your sound changed quite a bit and you were working on much more heavy material. What are some of the strongest memories from working on ‘If Only for a Moment’?

We went back on the road and started writing our own material again. We discovered this “harmony guitar” idea, which we actually developed when we were living in Paris. We have been in a hotel right across the club and we’d go in there in the afternoon and practise and eventually we ended up with this “harmony guitar” bit that became our trademark for Blossom Toes’ second record.

“The beatniks and the society crowd met and danced to our music”

What were some of the gigs that stayed close to your heart?

One is when The Ingoes played at The Bus Palladium in Paris. We had a residency there for about four months, I think and gave it to Arthur Brown when we left. We actually started the club we were known to the club owner. They wanted a bigger venue from the place they were running. So we went and there was nobody there to begin with. We were playing in empty rooms, but we had a couple of different groups of friends. For example we were friends with all the beatniks who would sleep under the bridges in Paris because they were the ones who could provide us with hash, which was of course an important element of our work at the time. Thankfully I have given that stuff up a long time ago. At the time we bought all the hash from them. Great guys. We asked them if they would come to the club, because we didn’t have the audience so they came down and then we also had made friends with several society people from Paris. (Bob Dylan showed up in this club after his gig, The Who showed up and that sort of thing.) We made friends with this local society and asked them if they would come to see us. The beatniks and the society crowd met and danced to our music. Promoter smartly brought a camera man down there and made a big fuss about how this is happening. How could the two groups of people rub shoulders together successfully? That kicked the club off and it’s still going. On a great day, we had people like Salvador Dali to Henry Fonda visiting Bus Palladium.

Did you experiment with psychedelics?

Yes, absolutely. We took quite a lot of acid when we came back to London. I found acid very interesting. It’s a dangerous drug. I don’t recommend people taking it, but I have to say my experience was 90% good. I had a couple of things which I would describe as a bad trip, which was pretty scary. I survived it, but some of the visions that I had when I was exceedingly high were most interesting, I found. I reckon that a large part of the brain has not been used before. Well, I’m Irish, so of course my brain is absolutely brand new. I haven’t used it all [laughs].

What was the songwriting process like for the band?

Brian Godding and I normally write things separately and then collaborate on the arrangements. I liked him much better than I liked my own to be honest. He was definitely a more musical writer. I just occasionally had a half decent idea. For my band I collaborate mainly with Sam Tanner. I like collaborating in the room with the other writer. That was my favourite way to work with Rod Stewart and Steve Harley. You just sit down and start playing and see what you can come up with. You’re always gonna come up with something, I mean it might be just crap, but you’ll come up with something. That’s the nature of what you do. It’s a strange idea to write with somebody new because you feel like you go into room and get naked, because you can’t hold back any of your emotional process, so specially if you’re writing songs about love and relationships, you can’t bullshit, well I suppose you can, but it’s not a good idea. So you have to be honest and that’s good for you. A good way to explore where the songs are going is by being honest.

Would you like to comment on your guitar technique? Give us some insights on developing your guitar technique.

Several years, maybe 30 years, when I was in Rod Steward’s band Jeff Beck came out on tour with us and we had about a month of rehearsal which were really … haha, forget rehearsal in that band. It was an excuse to get together, play for half an hour and get down to the pub and hangout. We loved hanging out together. Jeff Beck sat in with us and then we would do half an hour of his own using our rhythm section, so I got off the stage during that point. He would get back on stage and play some of our songs with us and he was unbelievably good. Scary, wonderful guitarist. I got to know him a bit since those days and he was a lovely man, an excellent human being. He showed me some things that I still try to play now. He could do 16th note up and down on bass string with his thumb nail at high speed and then using the other fingers play a syncopated rhythm. I can do it for about a second and a half before I fall apart [laughs]. I liked the idea of playing with my fingers. The last ten years I have been using my fingers more and more and I love not having a guitar pick. I find that I don’t like using a pick anymore, although a couple of tunes require a certain style of strumming. There I will use a pick.

I’m self taught and got my first guitar lesson when I was 42 years old. I had six guitar lessons in Los Angeles, which were very helpful, but I tried to teach myself how to read music a few times, but my problem is as soon as I figured what the notes could be, then my ear takes over and I’m playing again by ear which is what guys like me do. I would always recommend people to get guitar lessons. I think you get a lot of shortcuts that way.

How was it to work with Julie Driscoll on her solo album released in 1969?

Some of that is lost in the mist of time. I remember we sang backgrounds for Julie Driscoll. I think I played on one track. It’s a bit hard to remember. Julie was a part of the family, because Brian Godding married Julie’s sister Angie and they’re still together, which is quite extraordinary. Congratulations to them, they are a lovely couple. Julie was brilliant, but sadly I can’t remember much about the making of that track.

What led to the formation of Stud? And tell us about those two albums you recorded. How come you were so popular in Germany?

An unusual band formed essentially by John Wilson, (he was drummer in Taste with Rory Gallagher) and Richard McCracken (bass player for Taste) so we started a power trio, but the direction that John Wilson wanted to take the band (he was the band leader) was in the style of The Tony Williams Lifetime, which was high technique, wild time signatures (I learned how to play 3 and 2 thirds 4), which I suppose some of us has to learn how to do that [laughs]. It just happened to be me that week [laughs]. It was odd, so eclectic. I was writing songs that very often have their roots in folk music. I never really feel the need to be terribly technical. In Stud the job was to be technical, so I tried really hard to be John McLaughlin, but I didn’t know what I was doing. I just made a lot of rackets and played as fast as I could and hoped that some would think that I was a jazz player. Unfortunately I got that entire thing out of my system so I don’t need to play like that anymore. Honour to all of them could spend so much time doing that, but I’m not one of them. I’m a bluffer. I think it’s best that I confess now [laughs]. We were popular in Germany, no idea why. I mean we needed a producer and had this dreadful bloke, Eddie Kennedy, who used to manage Taste. He was sort of a Northern Ireland gangster. I didn’t like him at all, but he came with the job. He came with the guys because he managed Taste and he put his son, a lovely guy, Billy Kennedy. He was given a job of being the producer, but hadn’t had a clue what he was doing. We needed a real producer, because you need somebody to advise and guide you when you’re in the studio. You are so busy thinking to play the right thing, that you don’t have any overview. As a producer myself now, I very often hire guitar players and very rarely play on the record myself because it’s hard to be objective when you’re the bloke in the room with the band. It’s really hard for you not to think if you’re playing right or what’s going on. It’s very difficult to do, but if you’re in the control room listening and not playing it’s much easier to have a bit of overview. That was one of the reasons it was crappy to work on those recordings. I liked working with the guys, they were great, lovely people and we laughed at ourselves when we were in Germany several times. They were so amusing. Eventually John Weider (bass player from Family) joined us on violin and guitar. He was very good. He showed me a lot of Nashville stuff that I still use now. Very clever country licks on the guitar. So then that fell apart.

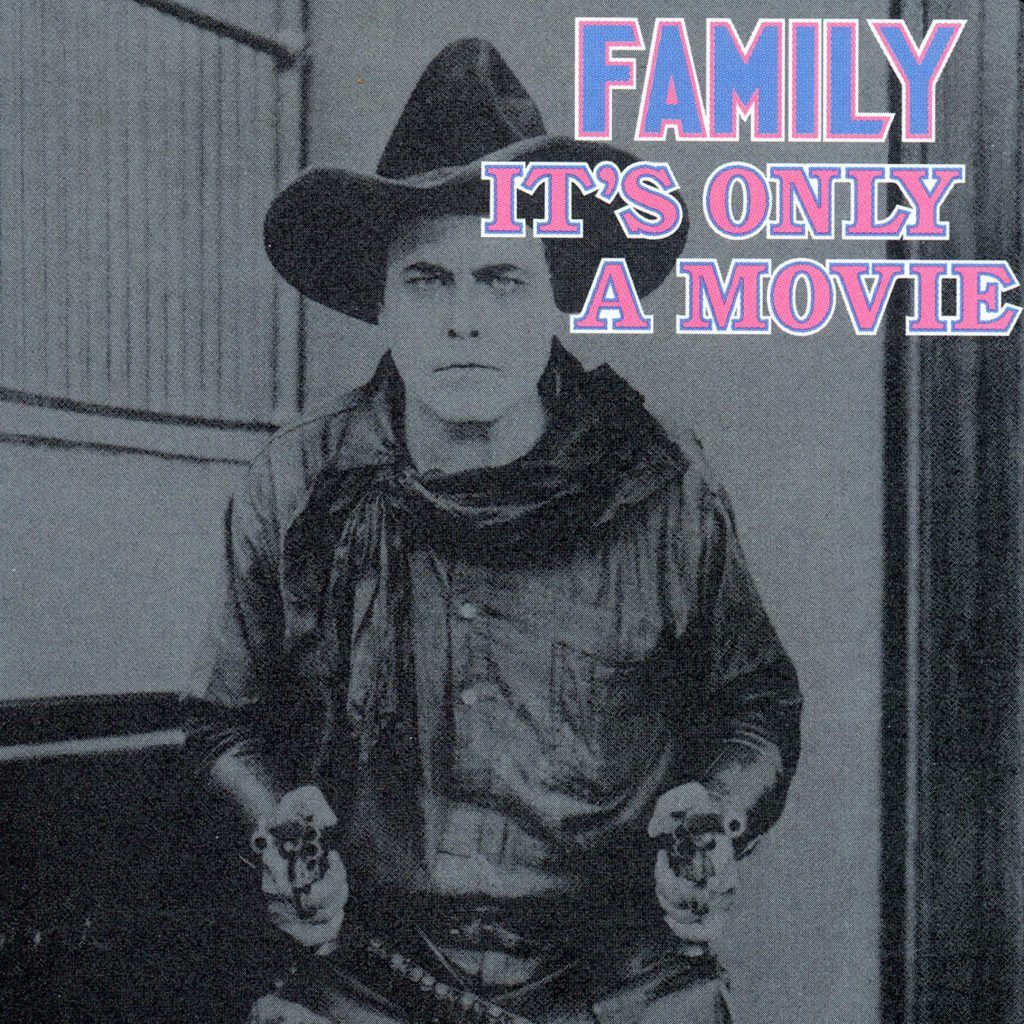

What led you to join the Family in September 1972? What was that experience like for you?

Stud fell apart and I joined the Family. I love Family. Roger Chapman is a very interesting character. He has a very powerful personality and he has this brutal honesty, which I found at first a little off putting and then eventually I started to respect it immensely, because it’s a very good way to live your life. You don’t bullshit anybody or anything. I’m not so sure that I can do that as well as he can, but I admire him for doing that. And Charlie Whitney was a creative writer and wonderful player. He’s retired in Greece or somewhere (if you’re reading this Charlie, I still love you, old pal!). We had great fun. Then we had Tony Ashton in the band – one of the silliest people I ever knew. Great piano player, sadly no longer with us. We toured around America. It was my first experience going to the USA as a professional musician. It was a fulfilment and a great dream to show up in the States and be paid for it. It was brilliant. We were opening for Elton John on the 13th week tour, which was highly intensive, and were travelling on the scheduled airline. You had to get up at six o’clock in the morning to catch different planes to get to the places where you were playing. It was fairly nuts, but brilliant fun and I started a friendship with Bernie Taupin, which is still going on.

We sadly couldn’t convince the American that we were worth having so we eventually gave up. What we did was we worked our way around Europe to Britain to make a load of money, because we were quite popular. We spent all that in America and we had to come back and do another tour of Europe again. That was very frustrating and we fell apart.

You also played with Shawn Phillips on that ‘Second Contribution’ album, right?

Yeah, I did play on that record. I think I remember one story of Rick Wakeman of Yes coming into the Trident Studio in London with a case of lager under his arm; 24 cans [laughing]. We all said, Rick, oh what a great guy. Thank you! He said, none of this is for you, it’s all for me. [laughin] He didn’t give us any, but he still played brilliantly. He was lovely and terribly funny. I like Shawn very much. A very interesting character. He used to be in the marines and now had this really long hair…

Would you mind sharing how you first met Linda Lewis?

I met Linda Lewis at the Procol Harum gig outdoor free festival back in 1968 (probably). Blossom Toes were playing it. I don’t know if she was there just as a guest or whatever, but we liked each other and I did a stint sitting in with her band which was called The Ferris Wheel. We did two weeks at the club in Geneva and started to cement a friendship that blossomed to romance and we were together for about ten years. Five of them unmarried and five of them married. She very kindly gave me my first opportunity to be a producer, because we produced her second record. It was called ‘Lark’. We produced that together in Apple Studios. It was great. We went on to tour the world with opening for Cat Stevens, who started a friendship with Alun Davies, his guitar player. One of the nice things about our business is that you sometimes meet people that are so kind-hearted that you have them as friends for the rest of your life. Sometimes he would be away, I would be away and it’s a few guys like that… James Honeyman-Scott from The Pretenders and I for example just hit it off like setting a building on fire. I wouldn’t see him hardly at all, but every time we met up it was like one of us had just gone out to put money in the parking meter and come back in. It was that kind of friendship.

Where did you first meet Steve Harley?

George Sweetnam [Ford] was the bass player in The Ferris Wheel and was quite a successful session player and after the gig I did, he obviously fairly liked what I was up to and Steve Harley was putting a band together when the original band broke up. He wanted to cut a track in Air Studios in London and asked George if he knew any guitar players and George recommended me. I just came to the studio and met Steve for the first time. We got on fine. It was a great little band. Pete Wingfield on piano, Simon Philips on drums, George Sweetnam [Ford] on bass and myself on guitar. We cut a couple of tracks for Steve and I think he put out a single. The next thing was he said do you want to play Reading Festival, which was quite a big event (30,000 or 40,000 people) and we were the second on the bill with two days rehearsal, which is not enough, went and did and that’s when all my cheat notes that I put on the corner of drums riser to refer to you know, how many verses, how many choruses before the end. After the second song a big wind came along and blew them all away [laughing]. Oh god, I still got the job anyway.

What was it like to have such a hit with ‘Make Me Smile (Come Up and See Me)’?

We had a hit with ‘Make Me Smile (Come Up and See Me)’. That was a fun band to be in. Stuart Elliott was one of the funniest people you can bump to. Steve Harley has a great sense of humour as well. George Sweetnam [Ford] and Duncan Mackay were great musicians. This song was my first number one. I could play on a couple of hits before, but this was my first number one and we were all over the place. We went to America and supported The Kinks. The Americans didn’t really get Cockney Rebel. Steve’s vocal style was something that they didn’t embrace. The band was kind of quirky too…

Life as a Cockney Rebel must have been busy… how did it all lead to your longtime collaboration with Rod Stewart?

Meanwhile Rod Steward comes to see the band play at the place called Roxy Theatre at the Sunset Strip and takes a bit of a liking of what I was doing. Somebody contacted me after and eventually that led me to join his band. It was quite difficult to leave Cockney Rebel, because we were successful, we were doing very well making lots of money, but there was no songwriting and I always have been a songwriter, even in Family I managed to squeeze a song in there. At this point songwriting was really important. It’s part of my identity. Steve guarded the songwriting part with quite jealousy and later on he stopped doing that and we wrote good tunes together. One strange enough was recorded by Rod Stewart.

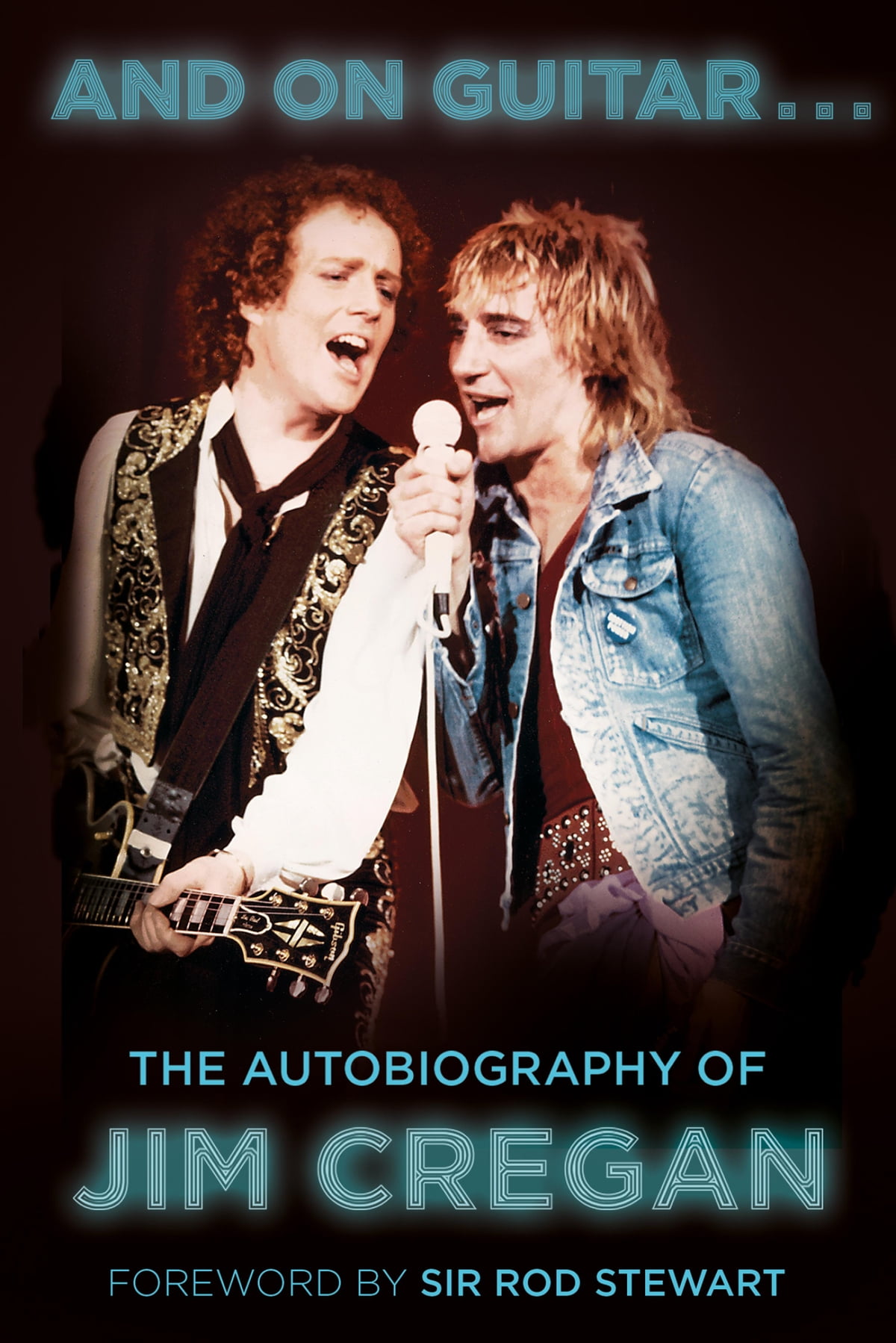

I guess the rest we can read in your autobiography, ‘And on Guitar…’, was it difficult to remember all the details from the past?

The reason for the title of my autobiography is that I was always introduced like that. “… and on guitar Jim Cregan.” I thought it was an appropriate title. Yes, it was pretty difficult to remember everything, but once you start, and especially if you have a wonderful co-writer Andrew Merriman who is a professional writer it’s easier. The book would never be finished without him, although he would agree that I did actually write quite a big part of it actually myself. It wasn’t done in the interview form. I would sit and type it out. I actually found out that I was better at writing lyrics than I was before, because I discovered there’s a puzzle to try to find an adjective or the right phrase and that puzzle is the same puzzle in writing a book or writing lyrics. Writing a book gave me some confidence that I didn’t have before. You have to take into consideration that I have been writing with some of the finest lyricists in the world. Bernie Taupin must be one of the most revered, delightful lyricists, and I write with Gerry Goffin, who often wrote with Carole King, and I wrote with Rod Stewart and Steve Harley. I bumped into a lot of lyricists in my life. I thought my job was to be a melody guy, so let’s leave it like that, but then after the book, I thought I can actually do both, so that’s what I do now. Sometimes I also collaborate with Sam Tanner et cetera.

Did it bring any (almost) forgotten memories?

Yes, I think once you start to dig around in your past… Andrew Merriman talked to relatives and friends about me as a writer and musician, and he would come back to me with things like that.

How did you cope with the last few turbulent years as an active musician?

I didn’t have a chance to play live, which I absolutely love to do. That was hard, but I also found that I did a lot of other stuff I have been meaning to do.

What else currently occupies your life?

I finished songs, I wrote new songs. I have a little studio with great equipment and I can make albums… so I would busy myself doing that. I’m a single father living with my now 17 years old daughter who is absolutely brilliant and we laugh and we cook and we go out and walk and do stuff together. We have a little boat to go on the river down to the beach…

Klemen Breznikar

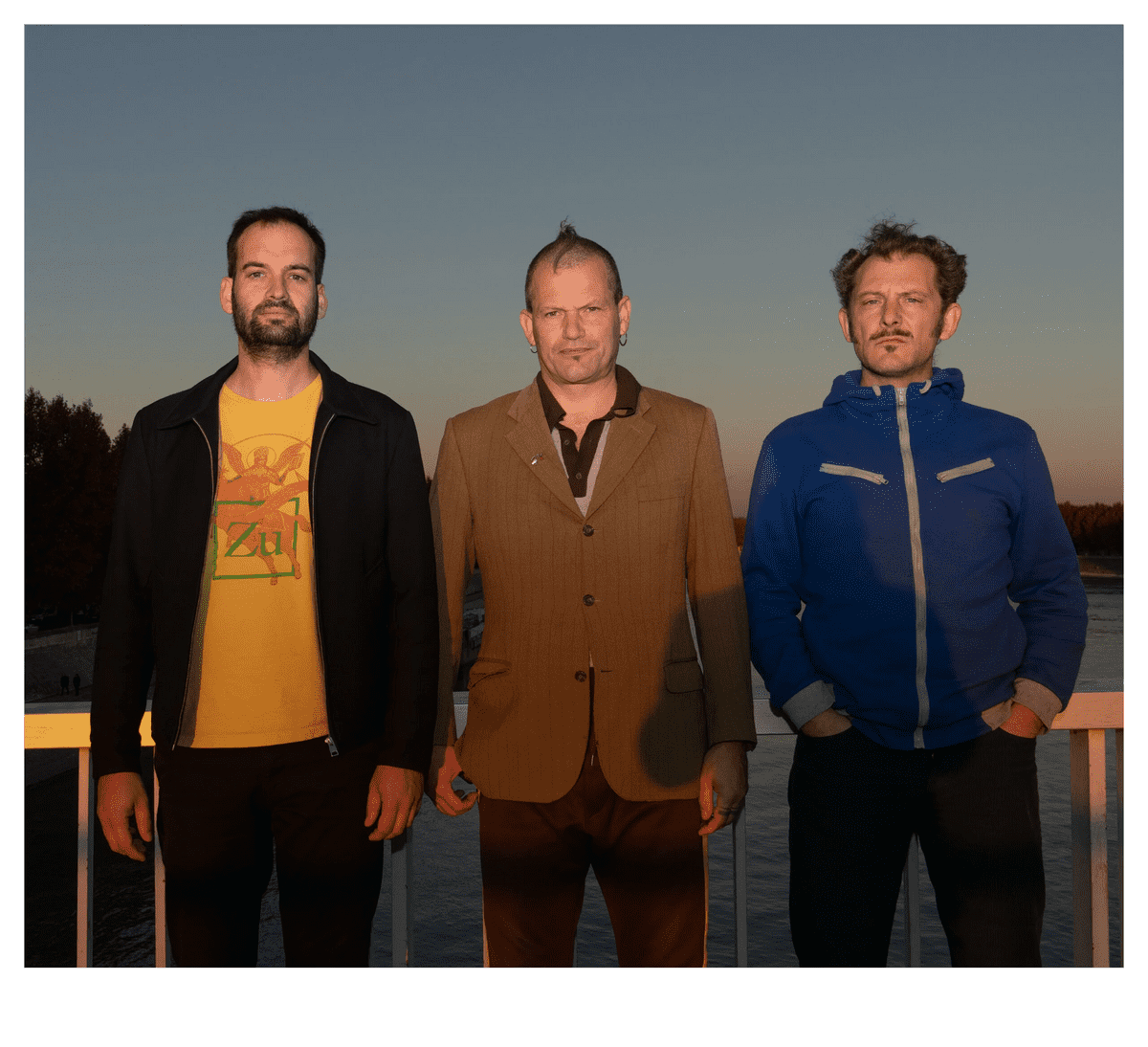

Headline photo: Blossom Toes (1967)

Jim Cregan Official Website / Facebook / Twitter / YouTube

Blossom Toes | Interview | Brian Godding

Blossom Toes – ‘We Are Ever So Clean’ (2022)