A History of The Outlaw Blues Band with Victor Alemán: Psych Blues at Its Best

Los Angeles in the 1960s was a city itching for something new. Bands came and went, chasing their shot. One of them was the Outlaw Blues Band.

Central to their groundbreaking sound was founder Victor Alemán, a Salvadoran-born percussionist whose early life, shaped by the distinct sounds of his homeland, provided a unique rhythmic foundation.

Alemán’s vision was instrumental in forging the distinctive sound that ultimately led to their signing with Bob Thiele’s Bluesway label in the late 1960s. The band’s two albums, ‘The Outlaw Blues Band’ and ‘Breaking In,’ featured a multicultural roster of musicians. However, it was Alemán, with his deep Latin roots and command of complex, nuanced rhythms, who pioneered the group’s signature fusion of blues-rock, psych-jazz, and Latin influences.

Reflecting on the band’s initial run and the challenges they faced, Alemán expressed a mixture of pride and realism. The group, he said, maintained their spirit despite limited resources: they “played with intense passion to the maximum on whatever composition we performed, always growing to new levels and looking for new musical horizons.” He added, “I believe that our band… was blessed and lucky to have done what we did, with the little resources and guidance that we had in our path.” Today, that “little path” is increasingly recognized as a significant, rediscovered chapter in blues-rock history.

“Our sound was unique because of our instrumentation.”

Where and when did you grow up? Was music a big part of your family life? Did the local music scene influence or inspire you to play music?

Victor Alemán: I was born in El Salvador, in the tropics of the American continent, a land filled with natural soundscapes. I grew up surrounded by birds singing, the sound and rhythm of the sea, and the wind whispering through the trees.

In the city, the soundtrack changed: cars, footsteps, voices, and the cries of street vendors echoed through the neighborhoods each day.

And, of course, there was the music on the radio. Television had not yet arrived in the country, so the radio was everything—our entertainment, our education, and our connection to the world.

Those ambient sounds taught me to listen from a very young age. I used to imitate birdsongs with my whistles.

At home, my parents loved music. My father had a large record collection that became my first true musical education. My early influences were mostly tropical: Cuban music, mambo, danzón, cha-cha-chá, and bolero, along with trios and mariachi music from Mexico, and merengue from the Dominican Republic.

My father also loved the great American big bands: Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, and orchestras from Latin America like Pérez Prado, Luis Alcaraz, and Pablo Beltrán Ruiz.

That mix of nature, city life, and my father’s records became my first musical foundation.

When did you begin playing music? What was your first instrument? Who were your major influences?

In 1955, when I was about ten, I traveled with my mother to New Orleans, a trip that changed everything. It was the first time I heard blues and rock and roll, and the first time I saw television. I remember watching Elvis Presley, Little Richard, Bill Haley and the Comets, Gene Vincent, and Ray Charles.

That trip planted the seed, opened my mind, and truly awakened my vocation and desire to become a musician.

When I returned home, I asked my parents to buy me a guitar. Of course, they said no. At that time, there were no music schools where I lived, and my parents wanted me to pursue an academic career as a doctor, architect, or lawyer. But my dream persisted.

At school, there were no music classes, only a large choir. I tried to join, and luckily I was able to, and I started singing.

Not exactly what I wanted, but I was already involved in music.

Soon after, I discovered the school had a marching band. At first, they told me it was full, but months later a drummer’s spot opened up. That is how it began. The marching band became my first real step toward becoming a drummer and musician.

What bands were you in before forming The Outlaw Blues Band?

By the time I was living in Los Angeles and attending high school, a friend told me he was forming a band. I shared my experience playing drums in a marching band back home and my dream of joining a real group.

He said I could join if I had a drum kit. I did not, but my aunt helped me buy a Pearl drum set on credit, the cheapest one available, and I promised to pay her back in installments, which I did.

Once I had it, I joined. We rehearsed every afternoon, playing rhythm and blues and Top 40 dance music. Soon we were performing every weekend at popular dance halls around East Los Angeles. This was around 1964 and 1965, and the band was called The Originals.

What was the first song you ever composed?

I do not clearly remember the first song I ever wrote, but I do remember the first one I wrote and recorded. It was called ‘Non Stop Blues,’ and we recorded it for Era Records as the B-side of a 45 RPM single. You can still find it today. It ended up on a bootleg compilation LP called ‘Ear-Piercing Punk,’ which is floating around online. The producers of that punk album included it without my permission, but it is also available to hear on YouTube.

Can you elaborate on the formation of The Outlaw Blues Band?

In 1964 and early 1965, three of the future Outlaw Blues Band members were still playing with The Originals. We were part of the East Los Angeles dance-hall and nightclub circuit, often hired as a backing band for well-known artists who did not travel with their own musicians.

We played behind performers like Rosie, Tony Allen, Jewel Akens, and others from the Oldies-but-Goodies scene.

In early 1965, the leader of The Originals ran into some legal trouble, and the band had to stop working. Suddenly, we were without gigs. I suggested to two of the guys, Phillip John Díaz and Joe Francis González, that we form a new band. We were tired of playing Top 40 covers just to stay employed. We wanted to create something original.

Phillip John Díaz, Joe Francis González, and I decided, without telling anyone, to leave The Originals and began practicing and playing as a trio.

At that time, we already wanted and were inspired to create and play original music, with an emphasis on and direction from all the new music we were hearing and seeing on television.

We were deeply inspired by everything we were hearing: James Brown, Ray Charles, B.B. King, Howlin’ Wolf, Jimmy Reed, Otis Redding, Bob Dylan, and all the Motown and Stax artists. At the same time, we were fascinated by what was happening in England: The Beatles, Rolling Stones, Manfred Mann, The Kinks, and so on.

A club owner in northeast Los Angeles liked what we were doing and offered to sponsor us as the house band at his Teen Club. He even let us rehearse there daily. We opened weekend shows for local and visiting artists.

One night, Billy Preston performed there, and I will never forget it. I played drums for his entire set, just him on the Hammond B-3 organ and me on drums. I did not know all the songs, so I had to improvise, but it was a great learning experience.

Playing as a trio made us tight and creative, but we needed a fuller sound. We brought in Rick Gilman, a rhythm guitarist we knew from The Originals, and his ideas enriched our music.

Our style and quality improved a lot, because we were now a quartet, with much more flexibility in the arrangements and the music in general.

Later, when Phillip stopped showing up for rehearsals, we replaced him with Leon Rubenhold, who played guitar and harmonica. Leon brought energy, strong ideas, and real drive.

Eventually, Phillip returned, apologized, and rejoined us. I decided that Leon should stay in the band as the harmonica player, since he was also an additional voice the group needed for the kind of music we were playing.

That is when we became a quintet, with a bigger, richer sound.

Then one day, by pure chance, Phillip John and Joe Francis went to a club, not to play, but to have fun. They happened to see a musician playing vibraphone, tenor sax, and flute. They were impressed and told me about him the next day. I had always dreamed of having someone who could play vibes or marimba in the band. It was rare and would give us a distinct sound.

The next day before our practice, Phillip approached me and told me his impression of the musician they had seen the night before.

I had always been, and still am, a fan of the music of Joe Cuba, Cal Tjader, Milt Jackson, and Bobby Hutcherson, where vibraphones are prominent.

I had also heard Manfred Mann, an English group that used that instrument in their band.

Manfred Mann’s music was not the kind of music we played, but there was still the possibility of adding that new voice to our group to create another dimension.

We contacted him, his name was Joe Whiteman, and invited him to a rehearsal. He liked what he heard and joined us soon after. His addition gave us new depth. The textures of the tenor sax, flute, and vibes brought an entirely new dimension to our music.

That is how we evolved: from a trio to a quartet, to a quintet, and finally a sextet, which was the evolution of the Outlaw Blues Band.

When and where did The Outlaw Blues Band play their first gig? Do you remember the first song the band played? How was the band received by the audience?

Our first performance as a trio was at the Teen Club in northeast Los Angeles. Honestly, I do not remember the exact songs we played; it was nearly sixty years ago. But I do remember the energy. The audience reacted with curiosity and enthusiasm because our music sounded different from what most other local bands were doing at the time. Later on, our instrumentation made us stand out.

What sort of venues did The Outlaw Blues Band play early on? Where were they located?

We played all over Los Angeles, places like The Ash Grove, PJ’s, The Magic Mushroom, The Cheetah, Pandora’s Box, the Hullabaloo at the Earl Carroll Theatre, Gazzarri’s, the Hollywood Palladium, the Ice House, and the Lighthouse, among others.

We also played at concerts, benefit shows, and Love-Ins in city parks. Sometimes we shared the stage with artists who would later become big names: The Doors, The Moody Blues, The Yardbirds, Bukka White, Taj Mahal, The Allman Brothers Band, and Steppenwolf.

We were local, but we were part of that explosive wave of creative talent that made up the Los Angeles music scene in the 1960s.

How did you decide to use the name The Outlaw Blues Band?

I was a big Bob Dylan fan, and I found the name in one of his songs. I added Band to it: The Outlaw Blues Band.

In hindsight, I sometimes think it was not the most commercial choice. People often misheard it when I said it, and I had to repeat it or even spell it out. I sometimes think a short, single-word name, like The Who, The Doors, Cream, or The Byrds, would have been easier for audiences to remember. But at the time, it felt right. The name reflected both our blues roots and our rebellious spirit.

Even now, single-word names still dominate: Google, Apple, YouTube, X. So maybe I was thinking more like an artist than a marketer.

What influenced the band’s sound?

Our sound came from a mix of backgrounds and cultures. Each of us brought something unique to the table. Joe Francis and I were from Central America. Leon Rubenhold was born in England. Phillip John, Rick Gilman, and Joe Whiteman were all from Los Angeles, but each came from different cultures, neighborhoods, and musical environments.

Our main roots were in blues and R&B. We were shaped by artists like Ray Charles, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, B.B. King, James Brown, Sam Cooke, Otis Redding, Little Richard, Jimmy Reed, John Lee Hooker, Marvin Gaye, and Stevie Wonder.

But we also carried strong Latin influences: Joe Cuba, Celia Cruz, Tito Puente, Pérez Prado, Machito, which naturally slipped into our rhythms and arrangements.

On top of that, we drew inspiration from jazz and rock innovators: Cal Tjader, John Coltrane, Gábor Szabó, Jimi Hendrix, The Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, The Kinks, Van Morrison, and Eric Burdon and The Animals.

We were sponges for sound, constantly listening, learning, and experimenting with new styles. That diversity became the core of The Outlaw Blues Band’s identity.

“We were musicians, not promoters, and because of that, the business side always came second.”

Did the size of your audiences increase following the release of your debut?

Not necessarily.

We never had the benefit of a strong manager to guide us, promote us, or handle the business side of things. Everything, from booking shows to networking, we did ourselves. And honestly, we did not enjoy that part. We were musicians, not promoters, and because of that, the business side always came second.

So while our music was gaining attention and respect, we did not have the right infrastructure to grow commercially. With proper management, I believe we could have reached a much higher level.

How did you get signed to ABC Bluesway Records?

That is one of those right place, right time stories.

One day we were playing a fundraiser for KPFK 90.7 FM, a listener-supported radio station in Los Angeles. I cannot remember whether it was in Pacific Palisades or the Hollywood Hills, but during our set, a man came up to us, excited.

He said he had been at a nearby house, heard our music, and at first thought it was a record playing. When he realized it was live, he followed the sound until he found where we were playing.

As soon as he arrived, he asked us who we were, where we were from, and told us he loved our music.

He also told us that he knew a famous producer named Bob Thiele.

I knew very well who Bob Thiele was because I had a large LP collection with the Impulse Records label, and Bob Thiele was the main producer for that label. He was also the producer of John Coltrane, a superstar musician whom I had been a huge fan of for a long time. I had collected many of his records and had also been fortunate enough to see John Coltrane perform at Shelly’s Manne-Hole in Hollywood.

He went on to tell us that he was going to inform the producer about the Outlaw Blues Band and promised that the next time Bob Thiele was in Los Angeles, he would set up an audition for us.

We had heard those kinds of promises before, people offering the moon and stars that never materialized, so we did not take it too seriously.

We really did not believe him. We thought he was just another charlatan in our lives, with that kind of nonsense we had heard many times before.

But to be polite, we gave him our contact information, said goodbye, and continued playing.

Some time passed. I had already forgotten about that character and his pitch when one day I received a phone call from him, letting me know that Bob Thiele would soon be in Los Angeles.

Of course, I said great, but I was still hesitant, not really believing him.

Some time passed, and he called me again and told me that Bob Thiele was in town and wanted to hear the band.

This time, we did believe him. We got ready. Bob Thiele arrived, we played a set for him, he liked it, and he told us he would soon talk to us about the possibility of a record contract, and that we should have enough material ready to record an entire LP.

We were still hesitant, but we held onto that seed of hope, that maybe this time what Bob Thiele had promised us would actually materialize.

We were very suspicious because another famous producer had been talking to us for a while, promising us all kinds of things and that he was going to take us to the top of the music industry. He was Richard Perry.

We had met Perry while performing during the filming of The Trip at the Sans Souci mansion, which had once belonged to Rudolph Valentino. He told us he loved our sound and wanted to record us. He brought us into Paramount Studios in Hollywood, where we recorded a seven-song demo. He promised to sign us and take us to the mountain top.

After recording the demo, he told us he really liked it and that he would soon give us a contract and once again, take us to heaven.

Well, in the clouds we were, when all of a sudden, he pulled the rug out from under our feet, letting us fall to the ground quickly, without a parachute and without any warnings.

Very soon we found out through the grapevine, not from him or anybody from his team, that he had signed Captain Beefheart instead of us and kept his silence without ever talking to us again.

That fall hurt us, it hurt us a lot, and it took time to overcome all the disappointment and deception that Richard Perry had inflicted with his unnecessary nonsense.

But we survived and got stronger, like always.

So when Bob Thiele came through, when it was real this time, it meant everything. It felt like all our persistence and frustration had finally paid off.

He got us a good two-year contract with ABC Bluesway Records for the recording of two LPs. He really gave us a good deal.

After signing it, Bob scheduled two days for the recording session. That is how our first record deal became a reality.

How would you describe your sound? I think you were ahead of your time for a blues-oriented band.

Our sound was unique because of our instrumentation. We had an excellent lead guitarist, a powerful harmonica player, a versatile musician on sax, flute, and vibes, a great bass player, plus a solid rhythm section that combined drums and timbales, something almost no one else was doing at the time. Our music created a very distinctive sound.

We mixed blues with Latin rock and psychedelic influences. That combination, along with Phillip’s guitar, Leon’s harmonica, and Joe’s multi-instrumental colors, gave us a sound that was truly ahead of its time as a blues-oriented band.

What is the story behind your debut album? Where did you record it? What kind of equipment did you use, and who was the producer? How many hours did you spend in the studio?

Never in my wildest dreams did I think we would have Bob Thiele producing our music.

I already admired him. He had worked with many greats: John Coltrane, Duke Ellington, Sonny Rollins, Charles Mingus, Archie Shepp, and Gato Barbieri, among others. He was the head of Impulse! Records, and he co-wrote What a Wonderful World, recorded by Louis Armstrong.

Bob Thiele had also produced blues giants like B.B. King, Muddy Waters, T-Bone Walker, and Joe Turner, and he was responsible for launching the Bluesway label under ABC Records.

So, for us to be signed and produced by Bob Thiele, it felt surreal. I could not have asked for more as a musician.

Bob was honest and generous. He let us establish our own publishing company, Amybaby Coal Train Music, for our original songs. Most producers used their own publishing companies to take a cut of the rights, but Bob did not. He was not a greedy producer.

We recorded the album at United and Western Studios in Hollywood, California, in 1968.

It was a really happy and most inspiring time of our lives. We had finally reached that goal we had dreamed of for years.

Please share your recollections of the sessions. What were the influences and inspirations for the songs recorded?

We were excited, focused, and full of ideas. The sessions went smoothly because we had been rehearsing nonstop for months. The band was tight, confident, and eager to experiment with sound.

Our influences came from everywhere: blues, soul, rock, Latin, and jazz, but most of all from our shared desire to make something ours.

Would you share your insight on the album’s tracks?

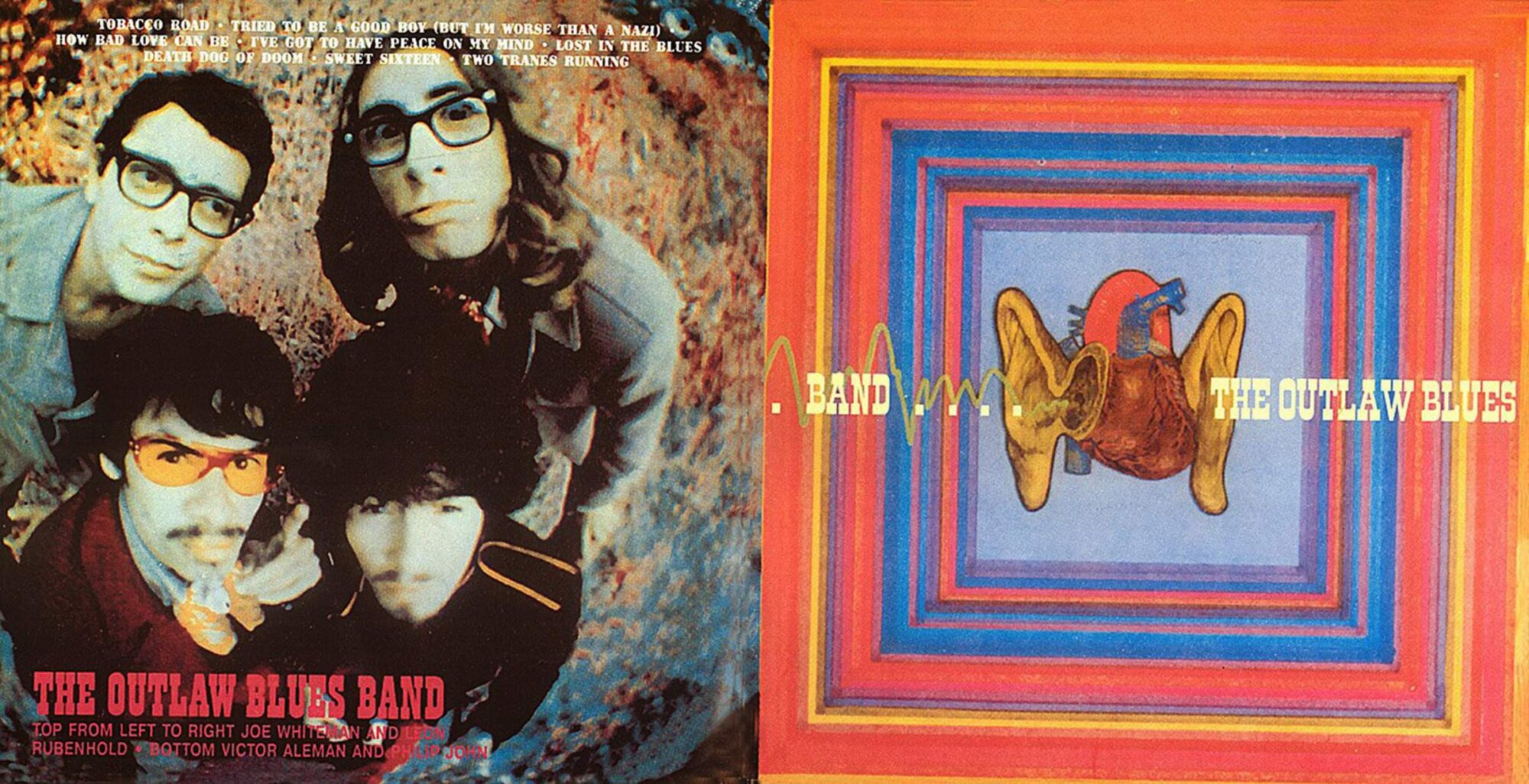

We recorded eight songs: six originals and two by other artists.

Our original songs were:

‘Death Dog of Doom’, Joe Whiteman

‘Two Trains Running’, Joe Whiteman

‘Lost in the Blues’, Victor Alemán

‘How Bad Love Can Be’, Leon Rubenhold

‘I’ve Got to Have Peace on My Mind’, Joe Francis González

‘Tried to Be a Good Boy’, Phillip John

The two covers were:

‘Sweet Sixteen’ by B.B. King

‘Tobacco Road’ by John D. Loudermilk

How pleased was the band with the sound of the album? What, if anything, would you have done differently?

We were very happy with what we recorded. We had rehearsed the songs enough to deliver solid takes, and being signed to ABC Records was an enormous step forward.

Looking back, I wish I had made a few different decisions as a leader.

First, I would have recorded more songs. We had plenty of good material we never put to tape. I also wish we had had more studio time to experiment further.

We recorded the album as if we were playing a live set, straight through, without thinking like studio musicians. In hindsight, we should have used the studio as a creative laboratory: layering instruments, exploring new textures, and adding effects. That is how you make a record that truly lives on.

Another thing I would have done is bring in guest musicians to expand our sound: Larry Young on Hammond B-3, Carmelo García on percussion, or Victor Pantoja on congas. All of them I knew, they were in Los Angeles at the time, and our budget could have covered it.

I also would have liked to have a lap steel guitarist to give us a different musical tone in our songs.

Musicians who create lasting albums often plan at least one song with hit potential, something that connects with a wide audience. That is what helps a record cross over, generate touring opportunities, and build longevity. I did not think that way at the time.

The cover artwork for your debut release is really beautiful. Who was the artist behind it?

The cover of our first album, The Hearts with Ears, was designed by Felipe León, a Salvadoran artist living in Los Angeles.

He said he was inspired by Dr. Christiaan Barnard, the South African surgeon who performed the first human heart transplant.

Felipe wrote this about his work on our album cover:

“Today, our heart, ears, soul, vision, and mind are essential to enjoy and perceive the message in the contemporary music of The Outlaw Blues Band.”

I also asked Bob Thiele if we could have a gatefold cover like the ones he produced for Impulse Records, and he agreed. That was a rare privilege for a new band.

Were you inspired by psychoactive substances like LSD at the time of writing the album?

No, not at all.

We never used psychedelic substances to create music. A few of us experimented briefly with LSD when it was being distributed for free at UCLA as part of Timothy Leary’s experiment and research. It was pure, strong, and fortunately we all came back from those trips, did not stay orbiting the purple ring of Saturn like many other people still are doing.

We tried it occasionally to expand our minds, not as a habit or a musical benefit. The same goes for hallucinogenic mushrooms, only on rare occasions, trying at that time in our very young naïve minds, following the teachings of Don Juan, that Yaqui shaman, about using sacred plants to access non-ordinary reality and perceive and comprehend universal communication directly without intermediaries, hahahaha.

On the other hand, we did not drink alcohol or use cocaine, heroin, or other hard drugs. We did smoke the herbs that came from Mexico, which luckily were of very weak quality and did not affect our neurons much.

We were serious musicians. We rehearsed daily, searched for gigs, and stayed focused on our goal, to record with a label. We saw ourselves as dedicated full-time musicians.

Did the band tour to support the LP?

No.

After finishing the album, our bassist Joe Francis, one of the founding members, left the band because of family issues. He did not even make it to the photo session for the cover, and his departure was a serious issue for the band.

We spent almost a year auditioning bassists, but the chemistry was never the same. Joe, Phillip John, and I were the nucleus of the band. We maintained a definite musical communication and a special friendship that went back many years. Losing that part of the foundation really hurt. We truly never recovered.

At the same time, we also had problems with our supposed manager. He did not want to work, did not want to pursue other work opportunities, and did not have any plans to further develop the band’s artistic life.

But the worst thing he did, which was unacceptable, was to single-handedly, without any permission or prior notice from any of us, title one original song on the album, which was released without us knowing until it was out on the market.

This horrible and offensive title was, “Tried to Be a Good Boy (But I’m Worse Than a Nazi).”

Completely against our philosophy and our beliefs. Nothing to do with the song we wrote. Nothing to do with the Outlaw Blues Band. Nothing to do with anything about us. This meant something only in his wicked and premeditated intentions. He really was an intolerable idiot with really a destructive intent.

We had to fight legally to completely remove him from our association. This was a waste of our time and energy, which we had to execute to get rid of him instead of working and continuing with our music.

Those conflicts, plus the long delay in releasing the record, wore us a little bit down. We feared the album might never come out, but eventually The Outlaw Blues Band and the People was released, with a bit of promotion from the record company.

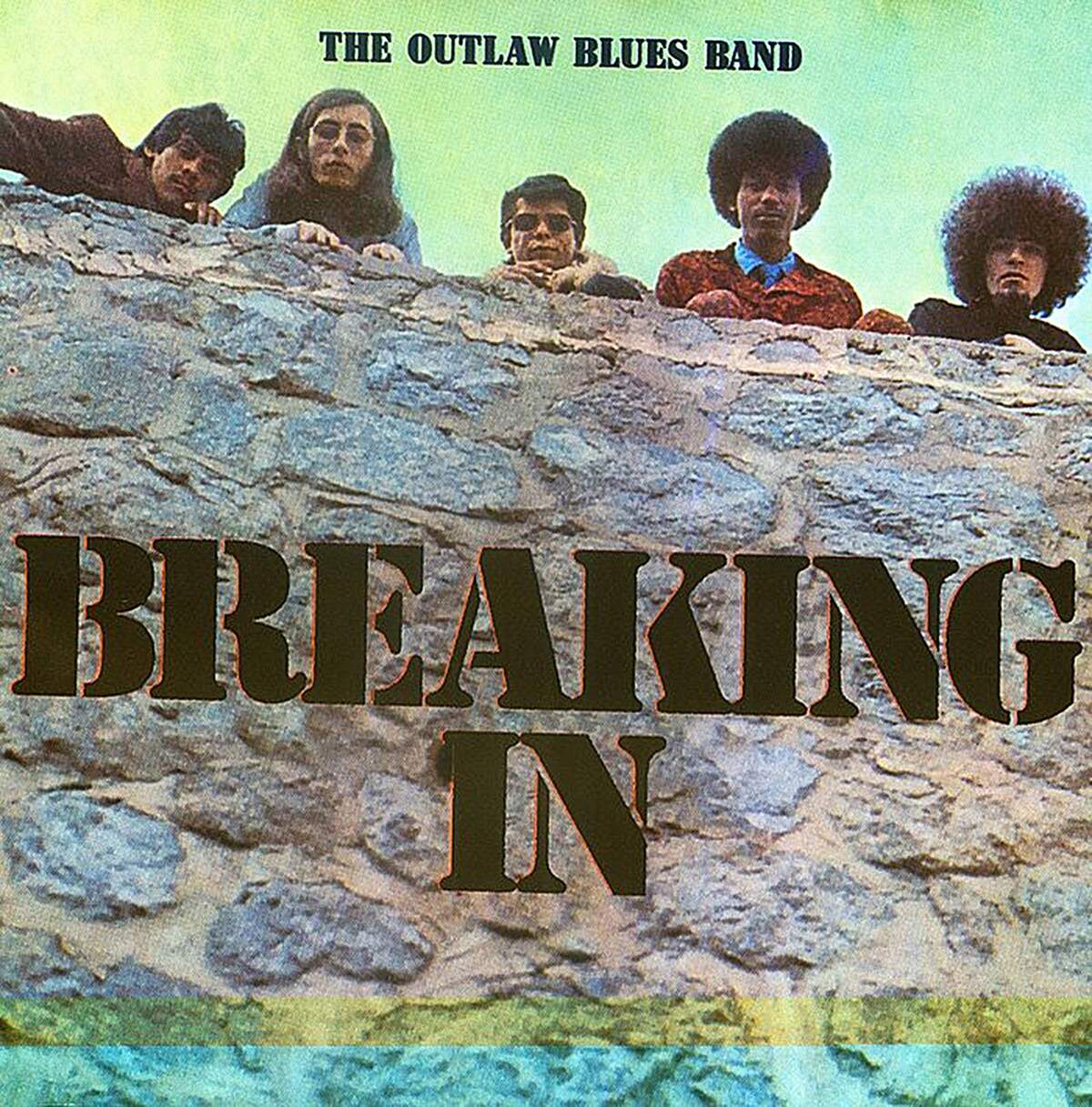

How about your second album, ‘Breaking In’?

After months of struggle, things finally calmed down. Our debut was out, and we felt hopeful again. Then one day I unexpectedly received a phone call from the vice president of ABC Records in Los Angeles, reminding me that the Outlaw Blues Band owed him an LP and that he wanted to have a meeting soon with me to discuss what he wanted for this next album.

We set up the meeting, and Phillip John came with me. Basically, when we met, the executive was direct:

“Every white kid in America wants to hear a blues album. That is what I need from you next.”

It was like a splash of cold water. Our music and sound had evolved; we were blending blues roots with progressive, Latin, soul, and psychedelic more and more. But there was no room to negotiate that day with the executive.

A few days later, Bob Thiele called me and confirmed the plan. We would record another album fast. He booked the United and Western Studios again in 1969 and gave us only two days.

We found a new bassist, Lawrence Slim Dickens, who also sang and contributed some songs, which we eventually included in our new album.

We rehearsed fast, hard, and recorded seven tracks, two of them ours, ‘MamoPanoShhhh’ by Joe Whiteman and ‘Day Said’ by Phillip John and me.

During the recording session, we had just finished recording ‘MamoPano’ when Bob Thiele called me into the control room of the studio to discuss what other songs we had ready to record.

He also asked me if we had any more songs in the style of ‘MamoPano,’ Latin, rock, blues, which he really liked, and told me he was enthusiastic to record more songs with that quality.

Also during the session, we improvised a tune that became ‘Deep Gully’. While I was in the control room talking with Thiele, the rest of the band started jamming with Bob Levey on drums, because I was busy talking to Bob Thiele. I told Bob Thiele it was okay for Bob Levey to keep playing and to let them roll tape. That is how ‘Deep Gully’ was captured, pure artistic inspiration in the moment.

In reality, Deep Gully was actually composed by Phillip John, Lawrence Dickens, Leon Rubenhold, and Joe Whiteman. They were the true composers who created the fundamental ideas of that song. However, unfortunately, only Lawrence Dickens was credited, and he alone received the composer’s royalties.

This song is the only composition on our album that has been used by several artists in different projects, such as motion pictures and other albums. It has been used in films such as This Is the End, Freedom Writers, and Judas and the Black Messiah, and has also been primarily used as a sampled track in the hip-hop community, most notably for ‘Muggs’ by Cypress Hill, De La Soul’s ‘Eye Patch,’ and the B-side to the Lafayette Afro Rock Band’s ‘Darkest Light’.

Other tracks included in this album are T-Bone Walker’s Stormy Monday, Len Chandler’s Plastic Man, and two more Lawrence Dickens originals, My Baby’s Left and Gone and You’re the Only One.

Bob Thiele titled the album ‘Breaking In’. Unlike our first record, we had little input on the cover or design in this one.

After the sessions, we kept performing for a while, but the bassist problems persisted. Lawrence Dickens struggled personally and became unreliable, with no transportation, missed rehearsals, and missed jobs.

I was already tired of dealing with the whole situation. I was the founder and leader since we started as a trio in 1965, and keeping a band together that long is harder than most people realize.

When ‘Breaking In’ was finally released, Hallelujah, the record was out, the company label did some promotion, but I was never able to resolve the bassist problem, so I decided to take a sabbatical, which was definitively the end of the Outlaw Blues Band as the original group.

Looking back on both albums, what would you have done differently?

Now, looking back at the two albums we made and seeing them from a different perspective, if I could redo them, I would record more material, hire additional musicians, and spend more time exploring the studio’s possibilities.

The studio is a laboratory for sound, not just a place to capture a live set. Think of the Beatles. They used the studio as an instrument, layering sounds until each song became a world of its own. Many Brazilian musicians also do this in their recordings. Sometimes they only record the sound of a matchbox in one of their compositions, and it sounds so full. It gives the impression that an entire orchestra is playing, and it is just the sound of the matches moving inside the matchbox.

Producers often rush artists to finish in a few takes, but true creation happens when you build layers, experiment, listen, and refine. That is how a recording becomes immortal. A concert fades when it is over; a record lives forever.

I also wish we had captured more of our early repertoire, songs like ‘Song for My Father,’ ‘GuachiGuara,’ ‘Fried Neck Bones,’ ‘Watermelon Man,’ and ‘Afro Blue,’ and other beautiful songs that we played.

Originally all of these songs had been recorded very well by other excellent musicians, but our versions featuring the sound of the lead guitar, the harmonica, and the vibes or flute or tenor sax in the style of the Outlaw Blues Band really had a very different and distinctive quality.

I really believe it was worthy of recording. That could have been our third album.

What happened after the band stopped? Were you still in touch with other members? Is any member still involved with music?

After The Outlaw Blues Band stopped playing, Joe Whiteman and I kept playing and jamming together just for fun.

We formed a group called Hard On for a while. We played around the city with different musicians, improvising world music, no pressure, no plans, without any hidden conditions, obligations, or expectations, just beautiful musical freedom.

Phillip John joined R.B. Greaves, Take a Letter Maria, and played with him for some time.

Leon Rubenhold is the only one of us who has continued playing music nonstop since his beginning. He has performed as a lead guitarist for Wilson Pickett, Bobby Womack, and David Ruffin, and has released several CDs, including Back to the Blues, A Close Circle of Friends, and Mucho Mojo. He has also written for soundtracks, other artists, and various projects.

I am still close with Joe Whiteman and Leon Rubenhold. We have a brotherly relationship. Sadly, Phillip John Díaz, Joe Francis González, and Rick Gilman have all passed on to the celestial heavens.

What are some of your favorite memories from the ’60s and ’70s?

The 1960s were an incredible time, so much great music, so much creativity and hope. We were surrounded by inspiration: Motown and Stax artists, Sam Cooke, James Brown, Otis Redding, Marvin Gaye, Ray Charles, Jimi Hendrix, Little Stevie Wonder, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Muddy Waters, B.B. King, Howlin’ Wolf, Jimmy Reed—the list goes on and on.

But it was not just the music. The 1960s were also about social movements and change: the Civil Rights Movement, the anti-Vietnam War protests, the Love and Peace Movement, the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr., and Robert Kennedy, the grape boycotts led by César Chávez and the United Farm Workers, Woodstock, the moon landing—all of it shaped our generation.

In the 1970s, I moved to the San Francisco area, to Marin County. I was hired to photograph the cover of the first album by Malo, Suavecito.

That opened the door to a new creative path. I kept working on diverse projects throughout the Bay Area. Those were joyful, creative, and progressive years, filled with purpose and discovery.

With my career as a photographer, I really enjoyed life in San Francisco, where I still have my heart, and where I also found the love of my life, in that beautiful city by the bay.

Is there any unreleased material by The Outlaw Blues Band?

Yes, just a few demos we recorded, some at Phil Spector’s Gold Star Recording Studios and others at Ray Charles’ RPM International Studios.

At Gold Star, we recorded ‘I’m a Blind’ and ‘Bad Little Girl’. At RPM, we cut ‘Everybody Needs Somebody to Love’ and ‘Nowhere 13’.

Unfortunately, those demos are in poor condition now. They were recorded around 1966–67, but they still carry the spark of what we were exploring back then.

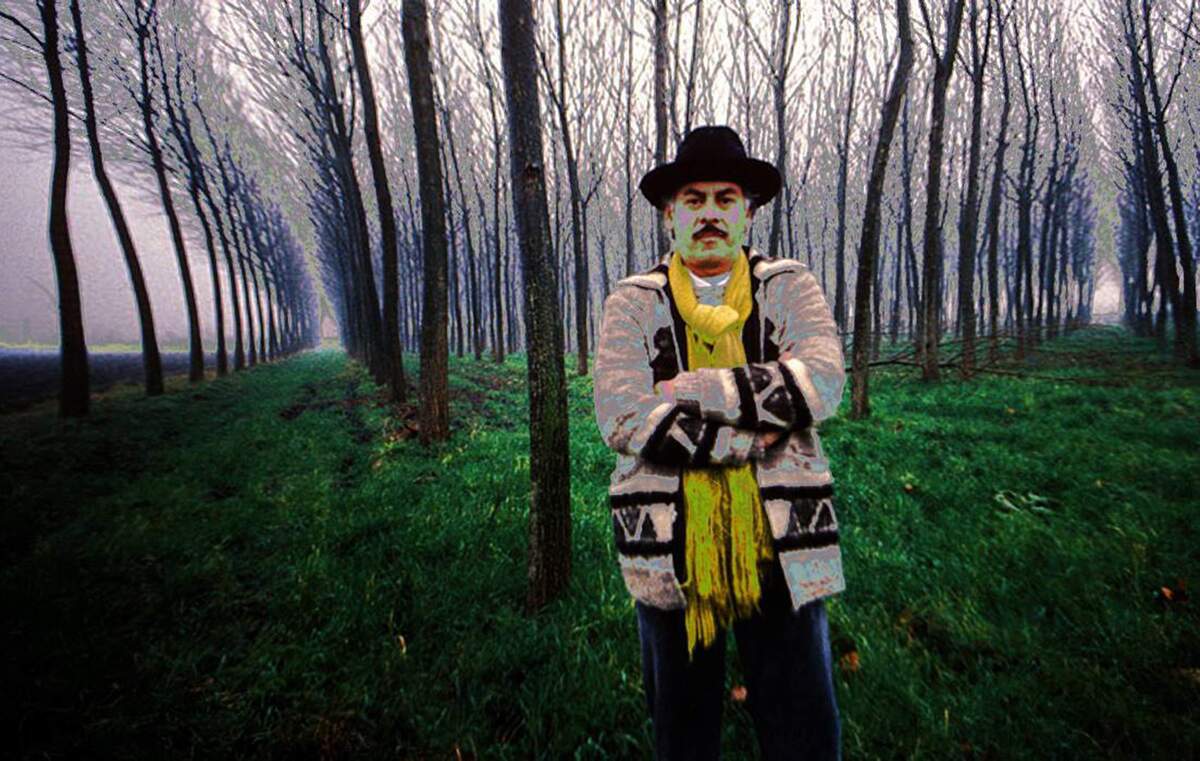

What currently occupies your life?

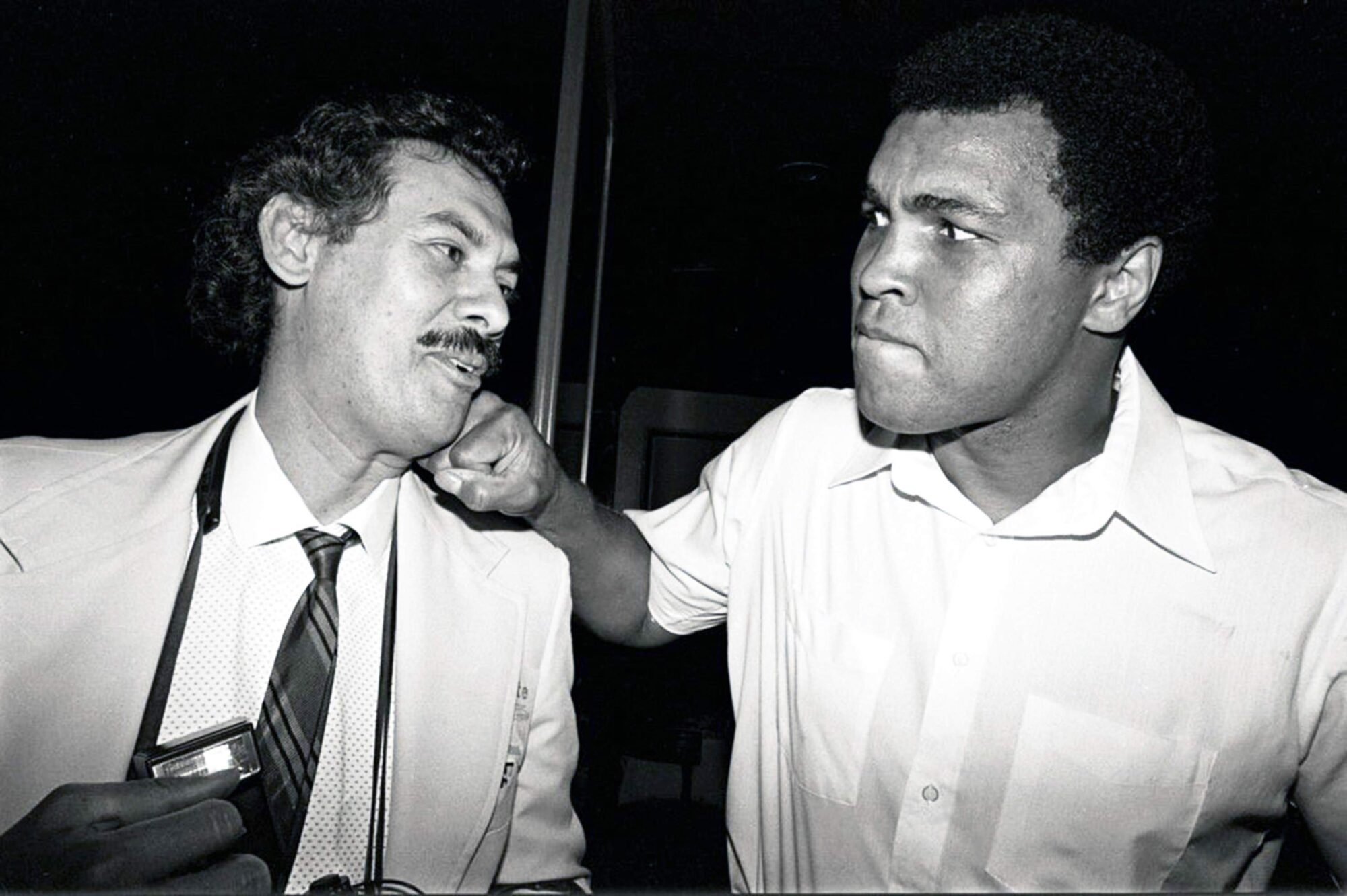

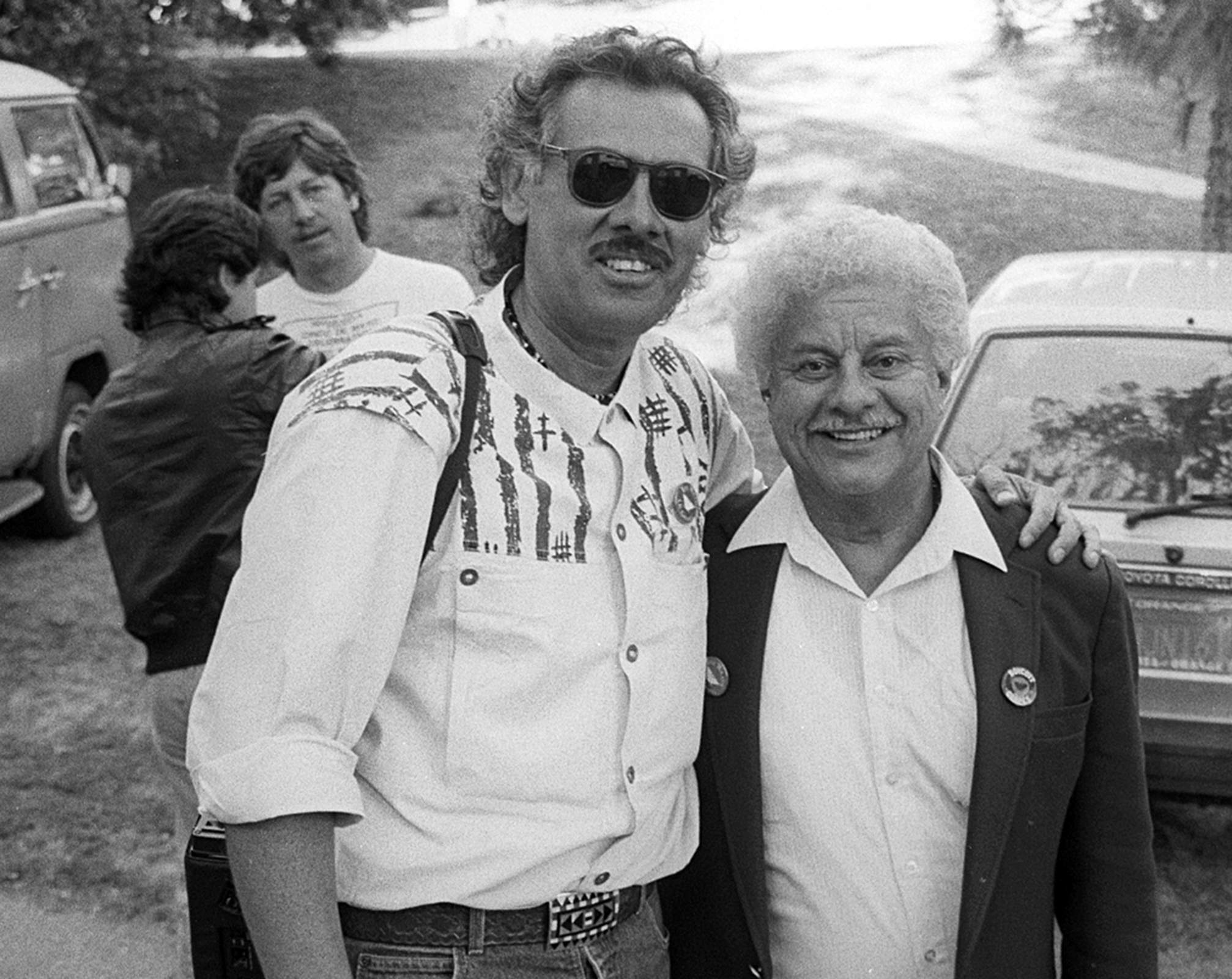

For the past 55 years, I have worked as an editor, photojournalist, and artist. Since the mid-1970s, after stepping away from full-time music, I have dedicated my life to visual historic storytelling, documenting the human condition, indigenous people, and the homeless across different countries.

My camera has also led me to photograph many notable people: Mother Teresa, Nelson Mandela, Miles Davis, Michael Jackson, Marlon Brando, Frank Sinatra, Muhammad Ali, Dizzy Gillespie, Grace Kelly, Popes John Paul II, Francis, and Benedict XVI; U.S. Presidents Barack Obama, Jimmy Carter, and Bill Clinton; Jacques Cousteau, and many others.

As an editor and publisher, I have worked with Banana Publications in Los Angeles and Le Gnome / El Gnomo in San Francisco, and later as managing editor for El Malcriado, the publication of the United Farm Workers. I recently completed a long-term role as editor of Vida Nueva, the official Spanish-language publication of the Catholic Church.

Now, after 61 years of continuous work, I am organizing my photography archive, a collection spanning more than five decades. I will research to find a university or museum where it can be properly housed and preserved.

One of my immediate plans is to publish a book of photographs about labor leader César Chávez, which I documented during my 10 years of working with him and the United Farm Workers. This project has been waiting patiently on the back burner; it is time to bring it to light.

And yes, at the same time, I am going to start practicing and playing some instruments that I have in my studio, to see what compositions emerge from my brain, which has always been, and continuously is, full of music and harmonies.

No regrets, only gratitude. The Outlaw Blues Band remains one of the most meaningful and unforgettable parts of my life. There is nothing more beautiful than creating music with friends.

That harmony and inspiration that has created my vertical aspect, the structure, the color, and the feeling for it, has shaped my entire existence.

From the bottom of my heart and soul, I thank Joe Whiteman, Leon Rubenhold, Joe Francis González, Phillip John Díaz, and Rick Gilman for all that great music, great times, and unforgettable memories.

I thank God that my entire life has been filled, and still is, with so much creativity, so much meaningful work, so many situations and lessons, and so much inspiration that I still draw on daily.

Let us keep playing the B-flat blues and straight ahead. Peace, and always peace in the universe.

Klemen Breznikar

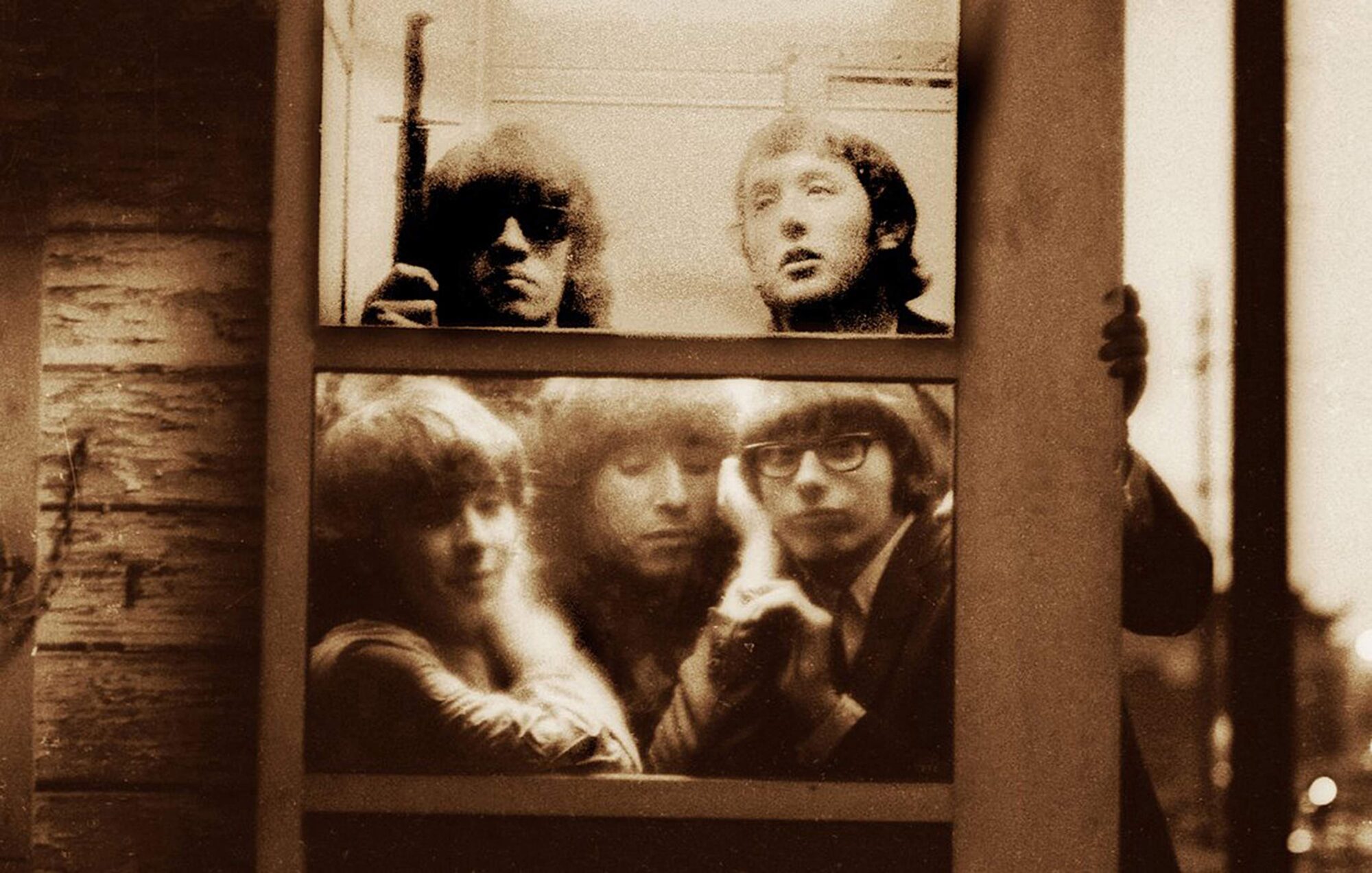

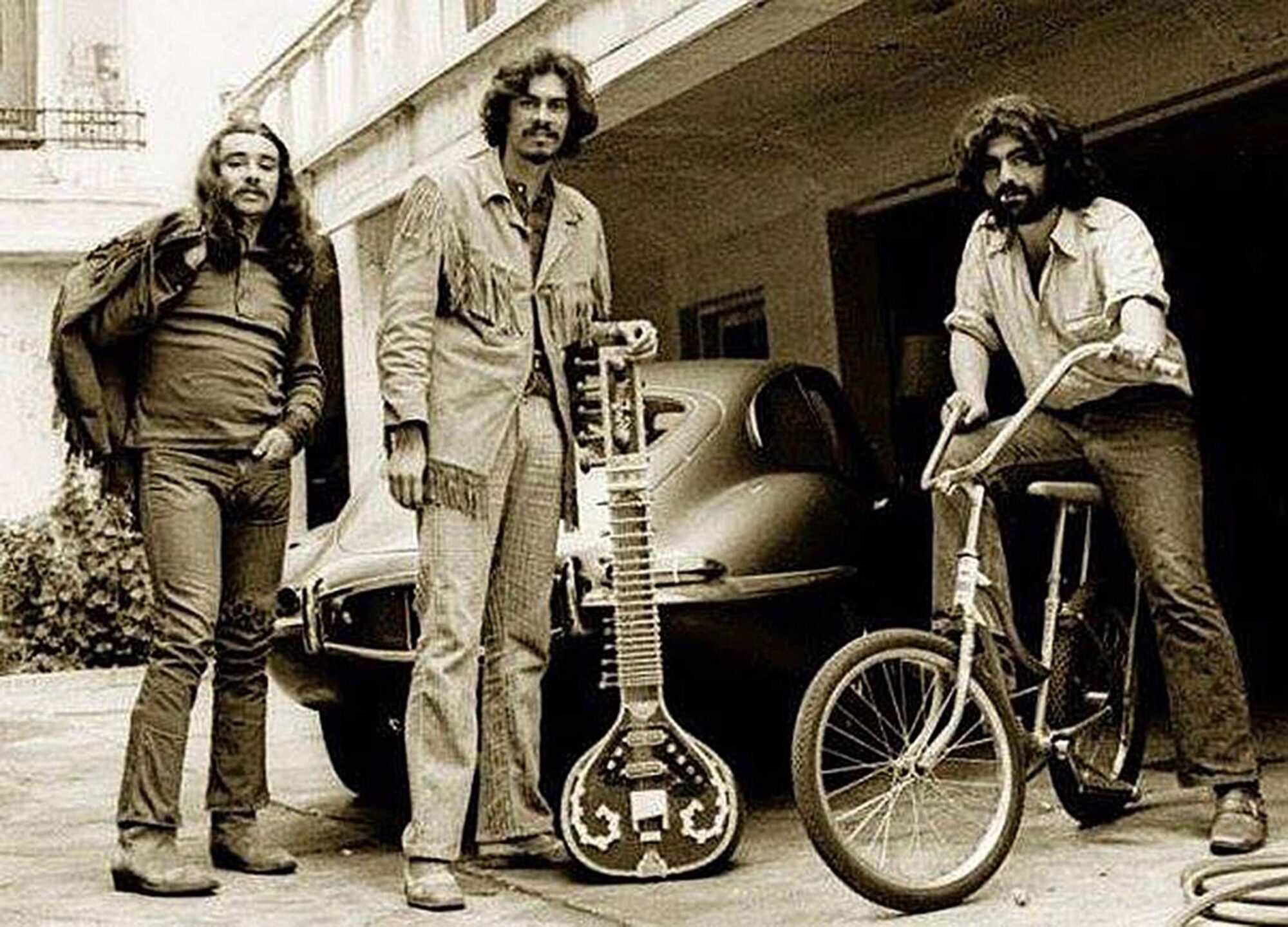

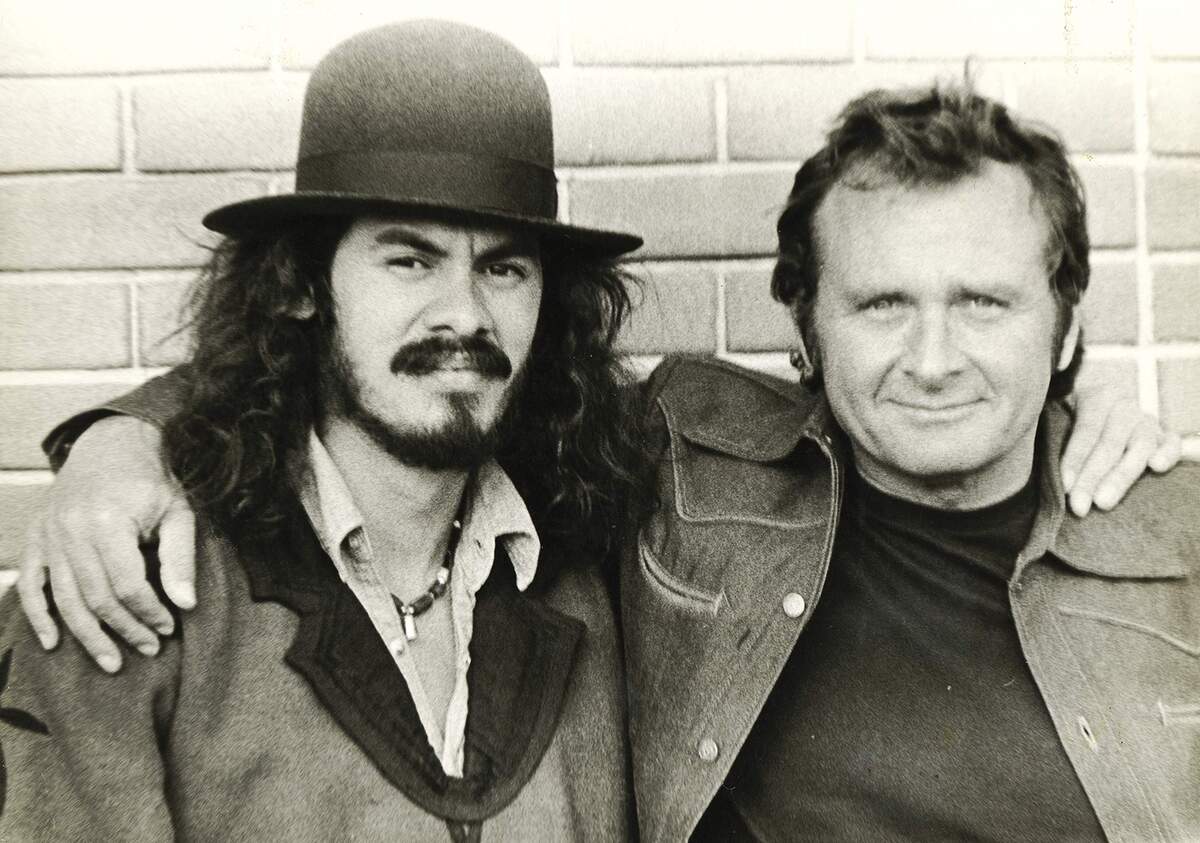

Headline photo: The Outlaw Blues Band when they were a quintet, during a photo session in downtown, Los Angeles, California. 1966. Clockwise from L to R: Joe Francis González, Victor Alemán, Rick Gilman, Leon Rubenhold and Phillip John Diaz in the middle. (Photo: Albert López | © Courtesy of 2mun-dos Communications.)

The Outlaw Blues Band Website