Edmonton’s Original Punks: The Nerve

There’s something about the Canadian prairie that makes good bands weird and weird bands unforgettable.

Isolation breeds invention, but it also breeds a particular kind of aggression. Maybe a need to be heard louder than the geography allows. Edmonton in the late 70s was no exception. While Toronto fine-tuned its art punk and Vancouver leaned into hardcore nihilism, Edmonton threw punches in every direction. One of the strangest, loudest, and most confrontational bands to crawl out of that snow-bitten oil city was The Nerve.

They were never Canada-famous. Maybe they never wanted to be. But what they left behind was loud enough to echo through four decades.

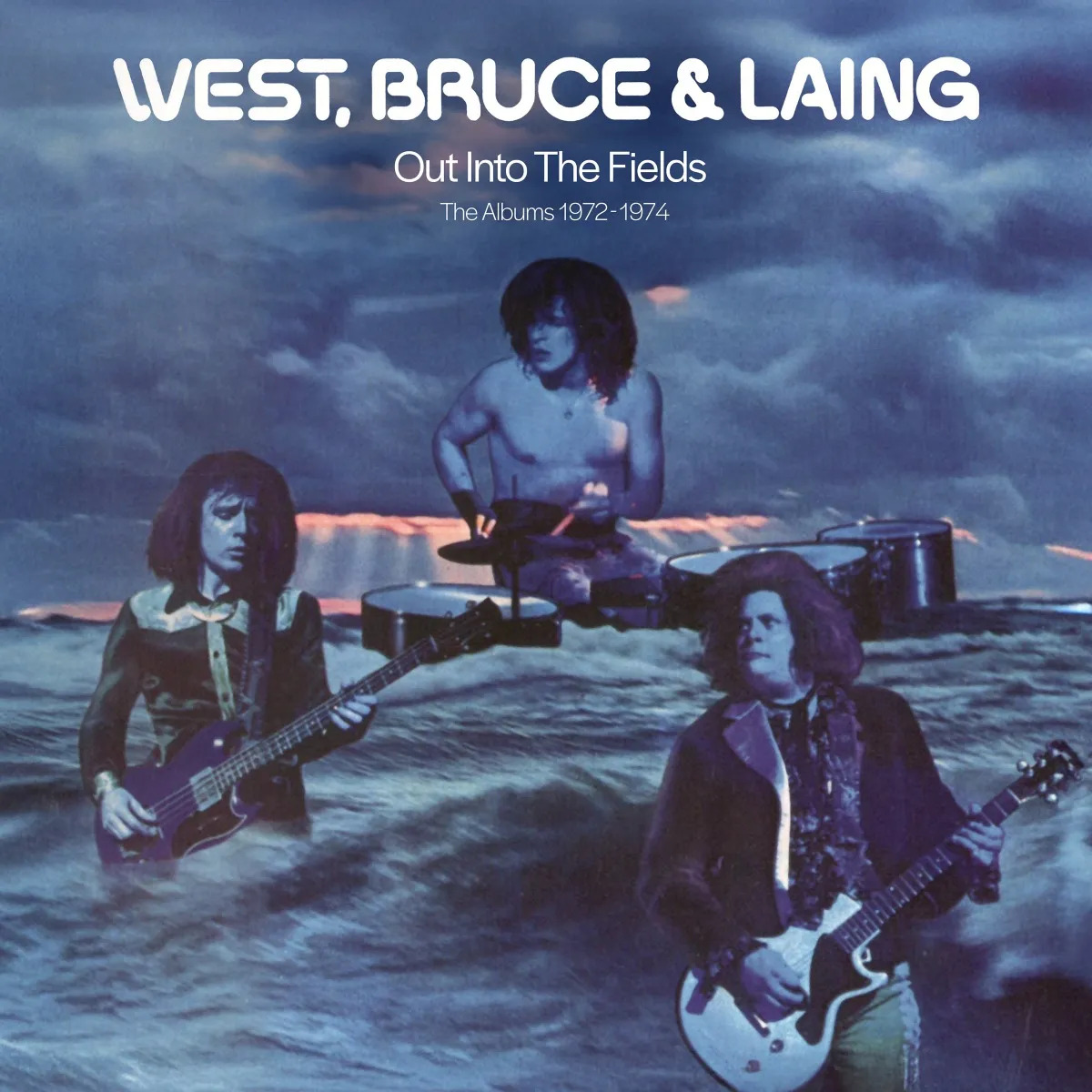

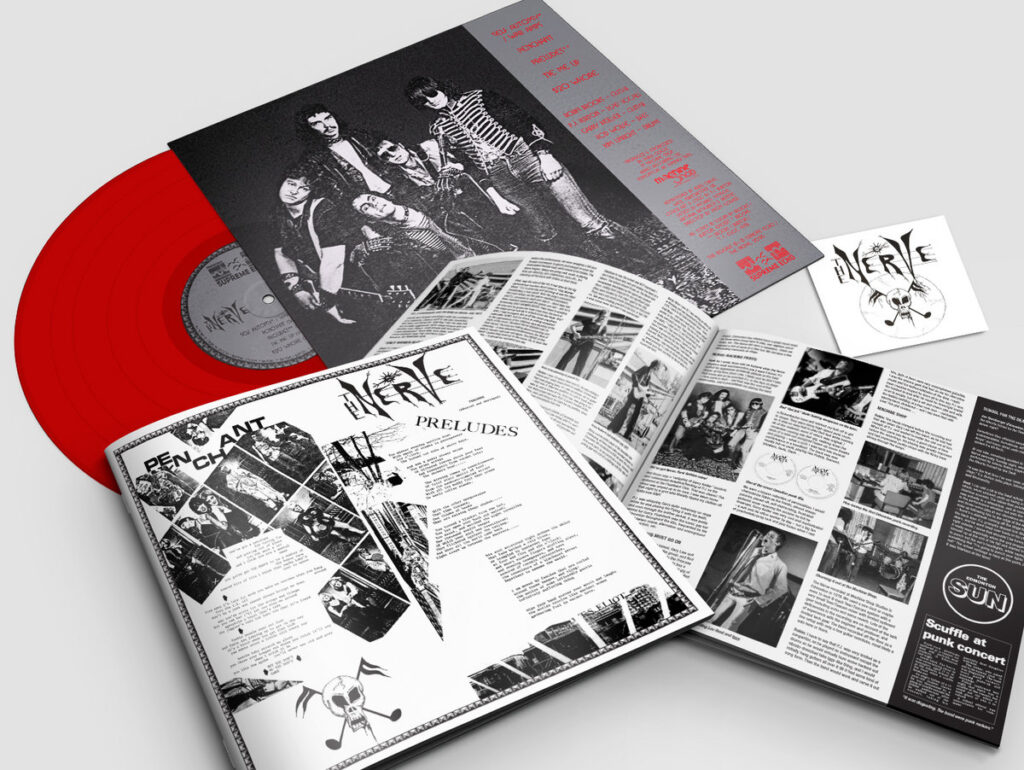

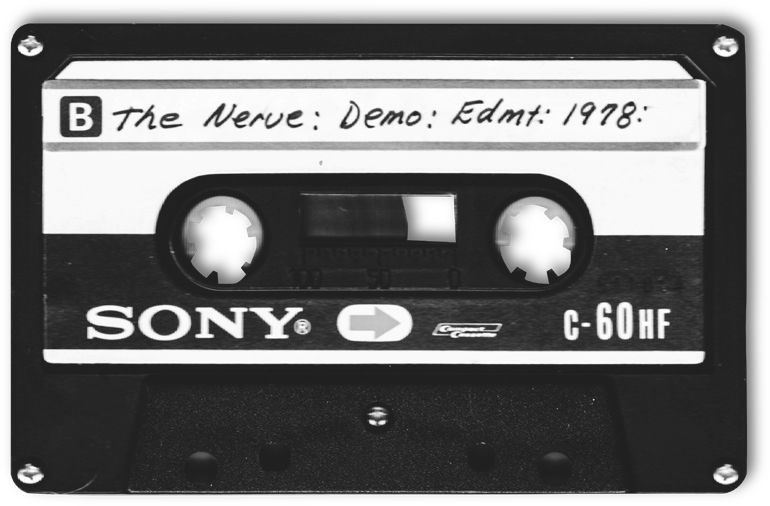

Thanks to the obsessive archival work of Supreme Echo, a Canadian label turned cultural excavation site… The Nerve’s scattered recordings have been assembled into ‘Self Autopsy,’ a document of time compiled with care. Like most resurrections, it stirs complicated emotions.

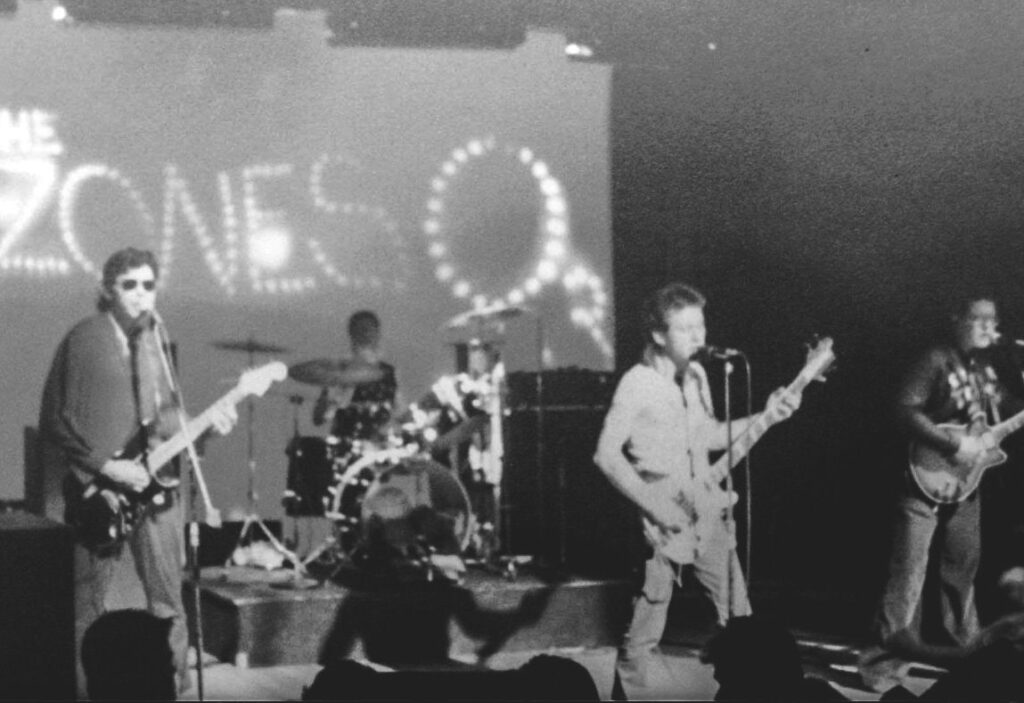

In late 70s Edmonton, The Nerve filled the punk void with songs like ‘Penchant’ and ‘Preludes’ (the latter cribbing lines from T.S. Eliot’s bleakest poems), they fused noise with unexpected art-school smarts. They were agitating in small-town bars that didn’t want them, dodging fists and beer bottles, and turning every gig into a craze!

Their frontman P.J. was a provocateur, sometimes literally eating the stage set. Guitarist Robin Brooks describes audiences in small towns ready to brawl unless fed Zeppelin covers. Instead, they got The Clash, the Ramones, and a punk sermon from a band that didn’t know how to compromise.

Guitarist Garry Keiller remembers the aftermath. “After The Nerve, I didn’t want anything to do with music for a long time,” he says. “It had burned itself out.” Years passed. Decades, even. The band scattered. Some played on. Some didn’t.

And then forty years later, Supreme Echo came knocking to stitch together this frayed legacy. The bandmates, scattered by time, reconnected through the project. “We came, we shocked, we appalled,” says Wolfe, still amused.

The Nerve were never meant to last. But their sound remained captured on those dirty, defiant, you even want to say poetic recordings. It won’t be in the canon, but in the static between stations. And in every kid who plugs in and plays too loud on purpose.

“We were different, to say the least!”

The Nerve was tearing it up before SNFU, before Edmonton had a real punk scene. Was it rebellion, art, or just sheer boredom that got you all in a room together with instruments?

Rod Wolfe: P.J. already had a band operating but lost his bassist (was that Garry Law, following the infamous punch he laid on PJ?), so he approached me since he knew me from the university in Saskatoon that we both attended. He knew that I had found the bass as my instrument of choice before I went to university. However, concentrating on studies, I hadn’t played in years! So I had a couple of weeks’ notice to get ready for a sold-out show at the Princess Theatre. Boot camp began immediately, and I immersed myself in the task. I was working as an engineer at the time, and every spare moment was spent learning the material and working on my technique on the recently purchased Rickenbacker bass. I loved the energy and raw power in the music, and I knew P.J. to be quite the performer. Why not rise to the occasion? When opportunity knocks, answer the call. It literally altered the course of my life. I was feeling strangely empty and incomplete just working in my tech world. Once I immersed myself in music again, all became clear. It completed me.

Robin Brooks: I was playing in bands around town or trying to and loved heavy music of all kinds. So when I came across an opportunity, I can’t quite remember how I found out about it all, whether I met P.J. or answered some kind of ad up in Keen Kraft music in Edmonton, but I gave them a call, got the gig as the guitarist, and The Nerve slowly hobbled itself together as initially a loud, noisy trash rock band.

Garry Keiller: I came on board after answering an ad in a local music shop. I had just moved to Edmonton from Winnipeg and was looking for musicians. I had been playing in bands in Winnipeg and was anxious to play again. The ad intrigued me, so I made the call. The idea of doing something a bit rebellious was appealing.

Edmonton in the late ‘70s…what did it feel like to be playing this kind of music in that environment? Did you feel like pioneers or just outcasts making a racket in a vacuum?

Rod Wolfe: Punk had just taken hold in Britain (’76 or so?) and had started to trickle into the scene here a year or two later. Certainly, a lot of clubs were wary of its anarchistic philosophy, not to mention noise level, mosh pit pandemonium, etc. We knew we were spearheading the new musical form coming from Britain, where so much great music, in my opinion, originated in the ’60s and beyond. I wanted to be a part of bringing that sound to my city.

Robin Brooks: I would say I always felt like we were outcasts, and it was pretty much a vacuum. Other traditional rock bands in town were covering all the usual fare of radio rock hits. Our setlist initially had glam rock things in it like Cooper and Kiss, but we soon started getting heavy into punky bands like The Reds, Vibrators, and The Dead Boys. Other bands just ignored us, were not curious, or barely even talked to us—until at least some of them started forming, like Silent Movies for example.

Garry Keiller: We were different, to say the least! Punk music was new to me, but being at the forefront of something new was a motivating factor. I never had the feeling we were outcasts, and I never had the sense we were ostracized by the music community.

“P.J. was a blend of Alice Cooper, Iggy Pop, and the NY Dolls.”

You mention that P.J. Burton wasn’t accepted by the “genuine punk” crowd. What the hell does that even mean? Was punk already codified into a uniform by then, or was P.J. just too wild even for the wild ones?

Rod Wolfe: P.J. was not your typical-looking punk or a mirror of the attitude of some of the classic English punk bands. He was more theatrical; he believed it was a performance. He was like the New York Dolls, who some may appreciate as a precursor to the punk era. They were arguably more glam rock in their style and presentation but certainly had a punk presence. P.J. was a blend of Alice Cooper, Iggy Pop, and the NY Dolls. So the “standard” punk crowd likely didn’t see him as part of their scene. He also had no issue with insulting the crowd—“you dirty rotten punks,” blah blah blah…

Robin Brooks: I’m not sure why he wasn’t accepted, but to a certain extent, that was true, as were the rest of us in a way. To some new punks on the scene, maybe we played too well or were just trying to jump on the bandwagon. They might have thought PJ was just an actor in the whole scene. Myself, I didn’t give a fuck what others thought about us. Just get out there and play hard. There are no job interviews in this kind of scene. Just blow your bag off—take it or leave it.

Garry Keiller: P.J. is an interesting character. He can be a great guy to hang around with, and a good pal. Very intelligent, has an excellent command of the English language, and very driven. However, he could be acerbic to the extreme, and could and did irritate the hell out of people. His onstage persona could be like that, resulting in his alienating audiences. My sense is that many of the hardcore punk crowd didn’t see him as the real thing.

When you were hammering out songs in a freezing basement or a garage, did you ever think, “This is gonna matter,” or was it just about making noise and seeing who could keep up?

Rod Wolfe: Being 50/50 scientist and artist, I needed some music in my life to balance my tech world. I realized early on that I needed both, and the right balance, to be personally fulfilled. I don’t know that I ever thought it was going to be something groundbreaking or overly significant, and I am very humble when it comes to considering my own talent and the validity of much of the music I’ve been involved in. My satisfaction came from just doing it and enjoying the experience, and hopefully entertaining some people along the way. It’s the journey, not the destination.

Robin Brooks: I think that’s true. We felt, when we started getting those original tunes down and pistol-whipping the shit out of them in a basement, that this did matter. I know I felt it. Sure, this could stand up to the punky music out there. Just keep at it. It’s not easy to get something good. Tons of Brit and US bands in this new wave and punky scene had lots of help sonically and on record.

Garry Keiller: Thankfully, we didn’t have to suffer freezing garages. Very “un-punk” of us. We were in a heated basement in a nice house. We did think that this movement mattered. Every once in a while, the contemporary music scene needs a good kick in the nether regions. We were kissing goodbye to the disco era, which none of us were enamoured with. The raw power and simplicity of punk was, for me, a welcome breath of fresh air. Punk was born in CBGB’s in New York, and moved quickly to London after Malcolm McLaren experienced the New York punk scene and created the Sex Pistols. So, I saw this as important.

What’s the song or performance where you felt like The Nerve was untouchable — like, for one moment, you were the best band on the planet?

Rod Wolfe: I have to say, I don’t think I ever felt that, although the first show at the Princess Theatre, where we came into a cheering crowd in a full theatre, about 300-plus people, and the response during and at the end of the performance was probably my most electric experience. And the first one, to boot.

Robin Brooks: I’m not sure I can answer that as far as a gig goes, although there was a gig we did in Calgary in some arena which was pretty good. On-stage dancers, etc., fleshing out the mood of us sonically. And I think opening for bands like The Battered Wives, DOA, Subhumans, Pointed Sticks, and Goddo made us tight and really confident in front of those fans. Also, I know, stuck deep into songs like ‘Tie Me Up’ and ‘War Amps,’ I knew they were super heavy and choppy. And ‘Penchant’ had nice levels in it as it built up. That made me sure of what we were about and what we were doing.

Garry Keiller: I never felt the band was the best. We were different. I was not aware of any other band at the time, in our city, doing what we were doing. And that made us untouchable.

Looking back, did you feel you were making punk music, or were you just throwing sounds against the wall and punk was the label that stuck?

Rod Wolfe: Personally, I liked the speed, energy, and power of the music at the time. It got me back into playing quickly because it was so challenging. My chops developed significantly during that time. Although I appreciated much of the music, I never considered myself “punk” but did respect some of the ideas. Sex Pistols’ ‘Never Mind the Bollocks’ is a brilliant album for the time, and to this day.

Robin Brooks: I feel like we were. When you sit and write and play and chisel it all out, what is it anyway? People can call you whatever they want. You can label yourself, or others will do it for you. Just shut up and play. I couldn’t give a shit whether someone stuck shit through their skin or crafted up a Vivienne Westwood or Malcolm outfit or a safety pin parade ensemble. I never felt the fashion sense of it all.

Garry Keiller: We were making punk music. Our originals were certainly in the genre, and I’ll put them up against anything 999, Dead Kennedys, Ramones, etc. were doing.

Rod, you talk about moving away from punk and into the alternative sound of the ‘80s — was that a natural progression, or did punk just burn itself out for you?

Rod Wolfe: Punk became limited to me, fairly quickly. I crave groove, melody, vocals with harmony, interesting counter-melodies, and appropriate soundscapes. I started listening to the New Romantics movement, New Wave, Talk Talk, Visage, Ultravox, Depeche Mode (still significant to this day), The Police, early U2, Cocteau Twins, This Mortal Coil (all 4AD), Factory Records, The Smiths (Johnny Marr especially), Joy Division, then New Order, Happy Mondays, Magazine, endless amazing bands. The alternative sounds of post-punk in the 1980s were my favorite decade, and still are.

The Ozones leaned into New Wave, New Romantic, keyboards… was that an artistic evolution or an act of survival? Did you ever feel like you were betraying the energy of The Nerve?

Robin Brooks: No, not in any way. There was amazing music out there in the UK and US scenes. I guess for me, way more on the UK scene. Brilliant bands like Ian Dury, Devo, Gang of Four, Killing Joke, The Tube, and smoother offerings like XTC, Pretenders, and the absolutely brilliant Stranglers.

Rod Wolfe: This is answered in the previous question, mostly. As for betraying The Nerve, not at all. That was PJ’s vision and creation. I was just a participant. It did get me playing again, and I am thankful for that. The projects I did for the next decades were more of my making, or at least influenced by me.

You helped kickstart a movement in Edmonton, but history is selective. Do you think The Nerve has been written out of the story, and if so, do you care?

Rod Wolfe: Personally, I live 90 percent in the moment, with 5 percent keeping an eye on where I am heading in the future. I don’t really care at all. It was an enjoyable moment in the past, with good memories. I was honoured to play with Garry and Robin, great musicians. I have done myriads of projects since then, and just finished up 90 gigs in Vietnam and Cambodia. Living the dream, as my friends say. So much has happened in the last few decades. I think it is amazing that Jason has taken an interest and done so much for this project. I applaud him profusely for that.

Robin Brooks: I don’t think we’ve been written out. The fans and bands who were there know who we are. I think we have our own story, and fans and people in the local scene know what we did.

Garry Keiller: To be candid, I really had not given The Nerve any thought until Jason approached us with this project. Reliving this has been rewarding and fun, and it got Rod, Robin, and me back together in a way. I am so happy with the finished product. Some people here still remember the band to this day. Many bands have come and gone over the decades in this city, some remembered, some not. I can’t say that I care if we are remembered.

If someone put on a Nerve record right now—forty-some years later—what do you hope they feel? Nostalgia? Fear? A kick in the teeth?

Rod Wolfe: Hmmm, whatever they want to feel.

Robin Brooks: I think all of the above. People love to venture back to times they feel were really humming, and to a scene as they see that they were a part of it. We can hold our own.

Garry Keiller: I have no idea how to answer this question.

Tell us more about that single on Village Records. What inspired ‘Penchant’ b/w ‘Preludes’?

Rod Wolfe: I don’t know. The guitar work, rhythm, and general arrangement seemed fairly epic at the time.

Robin Brooks: I remember for ‘Penchant,’ P.J. was humming and singing out an idea, that is how he would do it in general. I picked up the Les Paul and figured out the key and basic chording and added the simplest changes. Garry would embellish this feel quite a bit to get a lot of the staccato machine-gun-type intro that pops out on the track. I was always coming up with punky or rock punk things, almost a runky thing if you will, and sometimes they would form into a song like Preludes. PJ would work on lyrics or adaptations in the case of Preludes.

Garry Keiller: Robin is the guy to discuss this. He was the music writer, PJ the lyrics. ‘Preludes’ is a poem by T. S. Eliot and is a disturbing and depressing description of existing surrounded by urban decay. I don’t know how P.J. came up with the idea to put this to music.

What’s one thing you’d want every kid who picks up a guitar and thinks they want to start a band to know before they waste their life on it?

Rod Wolfe: Enjoy the process, creativity, and pure joy of creating and speaking musically to people, but do not ever depend on it for your livelihood. I decided when I was young that this was a significant part of my life, but it was not everything. Be diverse, develop many skills, be adaptable and flexible. Love everything you do, give 95 percent in effort to all of your pursuits, in your work and your play. Success will follow. Believe me, I have lived it and I am reaping the benefits, especially in the last 20 years. Avoid having all of your eggs in one basket, if you know what I mean.

Robin Brooks: I would really say you have got to love it and that it is part of you, something you cannot separate yourself from. It is in you, it drives you. Most of the people I have worked with from Toronto to Vancouver all play music at some level, and some have had really good careers as working musicians.

Garry Keiller: You need to love music more than you need food, drink, sex, and sleep.

You almost got killed in Onoway, Alberta. What the hell happened? Was antagonizing the crowd part of the act, or were they just looking for an excuse to hate you?

Rod Wolfe: It was often, if not always, a part of the act. P.J. liked to push people to the limit. To be honest, I don’t remember the details anymore. Obviously we got out alive, ha ha.

Robin Brooks: I cannot remember this about Onoway, but in a lot of these small towns we were always viewed as weird, strange, and something you could harass when drunk enough. Although I remember being in St. Paul, Alberta, Garry would recall this, and the largely Native crowd was about to kick our asses if we did not pony up with some Zeppelin or ‘Cat Scratch Fever’ and the like. But once the Marshall half stacks got wound up, The Clash, Pistols, and Ramones worked their magic. Heavy is heavy. Loud is loud. And beer is beer. Where else are you going to go if you are a local?

Garry Keiller: Onoway, at that time, was a typical Alberta small town somewhat isolated from the cultural and music scene of the big city. Our agent must have had a mental meltdown booking us there. They wanted anything but a hard core obnoxious punk band. From verbal abuse and unplugging the PA speakers stage left, we were fearful for our lives. I think we struck and escaped in record time. P.J., of course, would never have thought to try to placate the crowd. On the contrary, he would infuriate them more.

You started a riot at the Klondiker pub—do you remember the moment it went from just another night to “Oh shit, we might not make it out of here”?

Rod Wolfe: Again, being someone that lives in the present moment, that has faded from my memory.

Robin Brooks: Yes, I remember being in the can attempting to take a piss, but I was kind of shaking a bit and I do not mean that. These huge biker types and various other regulars were not happy with the entertainment, us of course, and loved to scare the young skinny musician types to death, which by the way always works. So getting out as quick as we could was always a good plan. And P.J. did not help, because lots of times he would berate them and egg them on. I am like shut the fuck up you idiot, do not poke the bear.

Garry Keiller: Kind of like the Onoway experience. The other guys can clarify, but I recall tables and chairs becoming victims of the evening. The highlight was my being attacked by the bar manager. P.J. had the fantastic idea to make a large montage of Penthouse and Hustler magazine centerfolds, which he rolled up like a window blind, but bigger. Well, at the end of the ‘Hot Body Suite,’ a few songs strung together, he unfurled this abomination for all to see. That was the final straw for the bar manager, and I became his target. He was screaming at me to take it down. I was trying to get PJ’s attention before the manager throttled me. P.J. then took out his whip and whipped the thing to shreds, and then started eating it. I think that is when we ended up being banned from bars.

What’s the absolute dumbest thing any of you ever did in the name of punk rock?

Rod Wolfe: I avoid, to the best of my ability, doing dumb things for any cause. So I would have to say nothing in that regard. Not to say that I have not made many mistakes in my life, but lessons are learned and I move on.

Robin Brooks: I do not know how the other bandmates here feel, but in a way, keeping Mr. fucking goofball P.J. was a bad idea and a bad idea for our punky personality, if you will. We could have found someone else, and later on when we fired his ass, I think we became a good unit as The Ozones. Heavy and crunchy. Also, I did wrap yards and yards of hockey tape around my guitar body, thinking this was a great look and feel.

Garry Keiller: The only dumb things I can recall all took place on stage. Off stage, we were pretty normal. I had an office day job wearing a suit and tie. Cannot get more boring than that.

If you could go back to 1979 and give yourselves one piece of advice before stepping on stage, what would it be?

Rod Wolfe: I am happy with what I did and how we projected ourselves. I always did the best I could to be in the moment, deliver the best show I could, while feeling the audience and feeding back the energy twofold. I think most everyone did the same.

Robin Brooks: Don’t give up on yourself. Sure, you’re in a band with your mates and it is great, but you have to stick closer to your own self and needs. I gave in a lot to the scene and my various band members. I should have stuck to my instincts on and off the stage… and kicked P.J. in the bag at least once.

Garry Keiller: Don’t compromise. Keep it up.

Garry, you stopped playing for 10 years after The Nerve. Was it burnout? Or did you just need a break from whatever the hell that ride was?

Garry Keiller: Some of it dealt with personal issues. However, after The Nerve, I really had no interest in doing anything else with music. Playing in the local cover bands of the day had no appeal.

After all these years, do you still get that electric charge from playing music, or is it more of a nostalgic trip now?

Rod Wolfe: I am doing it now, for 10 years coming in Cambodia, and adding Vietnam about 6 years ago with Loopy Reggae, a duo. I play in a trio back home in Edmonton, both cover bands. I still occasionally do other gigs and am working with a NIN-type original band. Loving it all. I also played in several original dark wave or goth bands over the last 3 decades, some of my favorite genre, but my tastes are wide and I enjoy most anything that is done well. There are brilliant works in most all genres.

Robin Brooks: I always connect with my grimey loud inner self, whether it is an acoustic gig or a loud electric adventure. I love those times and the music from it. But day to day, you have to step forward. This record release is a great thing that lots of fans of this music will be hearing for the first time in its proto, almost runk or punk type nature.

Garry Keiller: I still love playing. Unfortunately, the onset of age and the arthritis in my wrists and hands has made it extremely difficult to play three full sets at our gigs, so I am done with my band at the end of June. I still jam with some friends occasionally and can bang out five or six tunes on keyboards in an evening. Guitar is out of the question now.

“We came, we shocked, we appalled”

If this is the last interview you ever do about The Nerve, what’s the one thing you want to set the record straight on?

Rod Wolfe: We came, we shocked, we appalled, we entertained, and love it or hate it, it was an experience.

Robin Brooks: Well, that it does not matter where you come from or what you are about. Again, there are no rules in the creative art form of music, as trashy and art-fucking-rocky or punky as it may be, or not be. Whether you are from London, New York, LA, or Edmonton, Tim-butt-fucking-two, just blow your load out. Have fun. Love it. That is what The Nerve did for the time it was around.

Garry Keiller: I can’t think of any detail where setting the record straight needs to be done. We believed in what we were doing, and we did it well.

You must be pretty stoked about Supreme Echo putting out ‘Self Autopsy.’ Any final thoughts on it? And how was it working with Jason?

Rod Wolfe: I was duly amazed that anyone would be interested in that 40-plus years after the fact. I am honoured. I am happy for Robin, as he connects with the past more than I. Joe is gone now, and Garry will advise as to his feelings. Jason’s dedication and effort has been nothing short of phenomenal. It has been a pleasure and honour to work with him.

Thanks, Klemen, for all you have done and are doing for this project. Respect.

Robin Brooks: Jason and his team put a brilliant package together for this Nerve release. I could not have asked for anything better. And like all good things, it takes time and patience. I know fans of this time and music will not be disappointed.

Garry Keiller: I can’t overstate how much I appreciate the interest and dedication Jason has shown in initiating and leading us through this project. He got Robin, Rod, and me together on a Zoom call with him, which was warm, funny, reflective, nostalgic, and an absolute delight. I think it was the first time in four decades that the three of us were together again. Jason kept us in the loop through every stage of the process and was very sensitive to our thoughts and ideas. Thank you, mate.

Klemen Breznikar

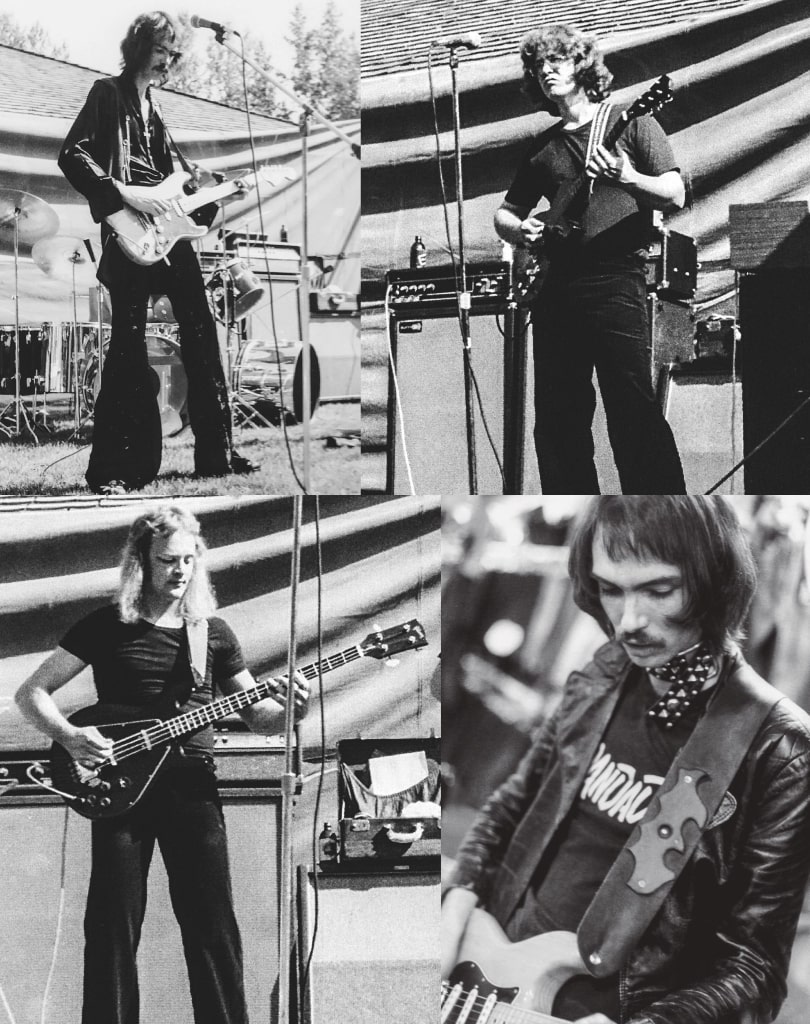

Headline photo: L-R: Garry Keiller, Robin Brooks, Rod Wolfe, and P.J. Burton at Borden Park.

Supreme Echo Facebook / Instagram / Bigcartel / Bandcamp