Castle Farm’s 1971–72 Lost Recordings Finally Resurface

If you’ve spent years knee-deep in the glorious muck of the underground, convinced you’d already squeezed every last drop of sonic gold from the ’70s, prepare for a jaw-dropper.

Just when you thought you’d heard it all, a fresh and utterly compelling roar bubbles up from the depths. We’re talking about Castle Farm.

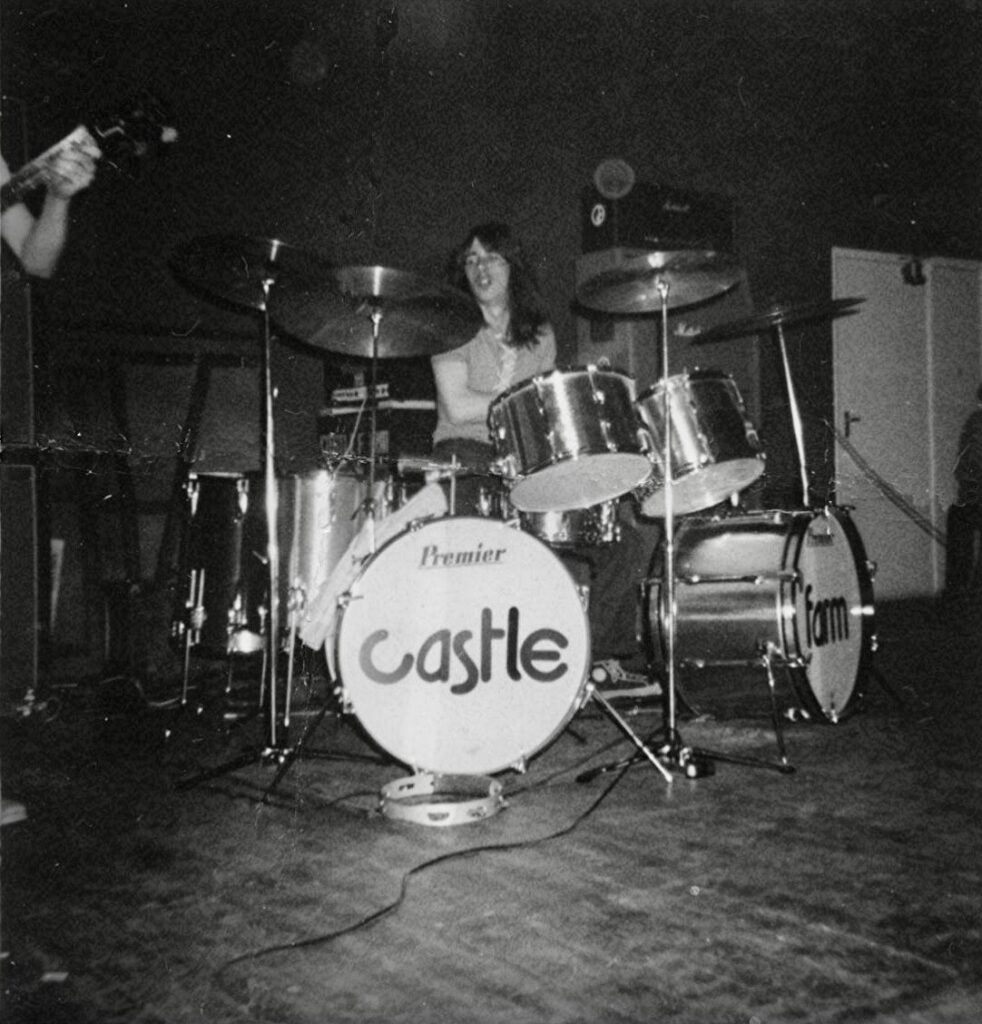

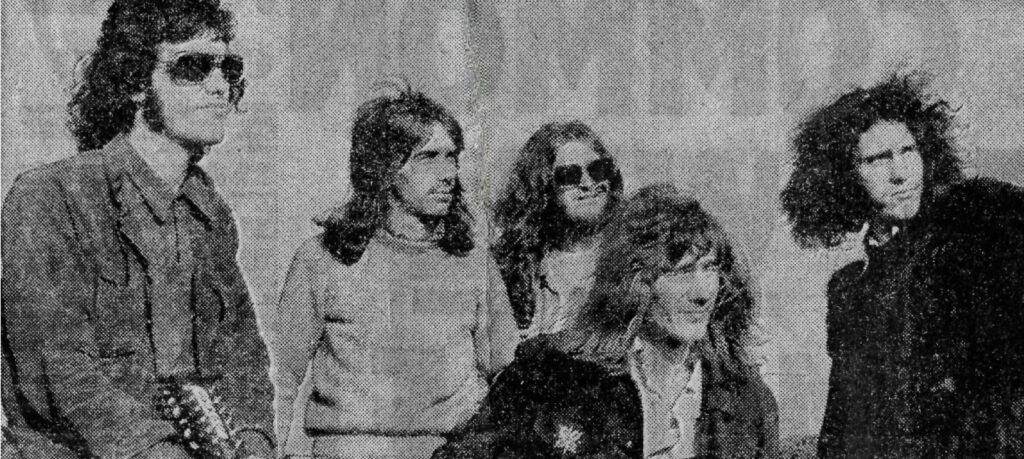

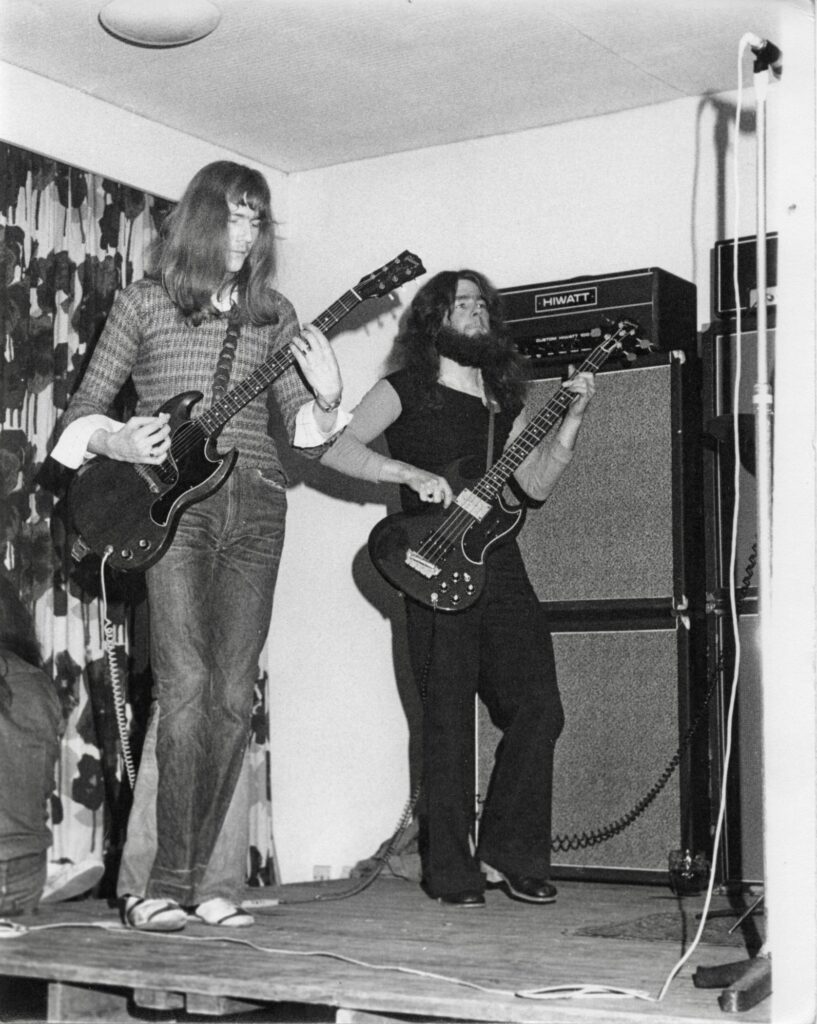

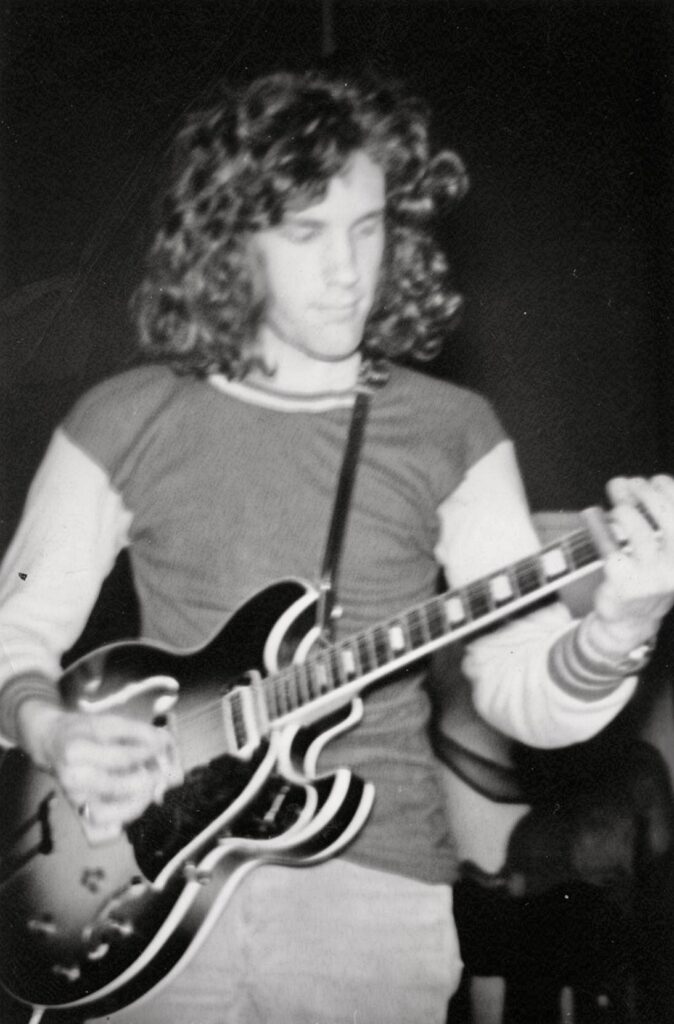

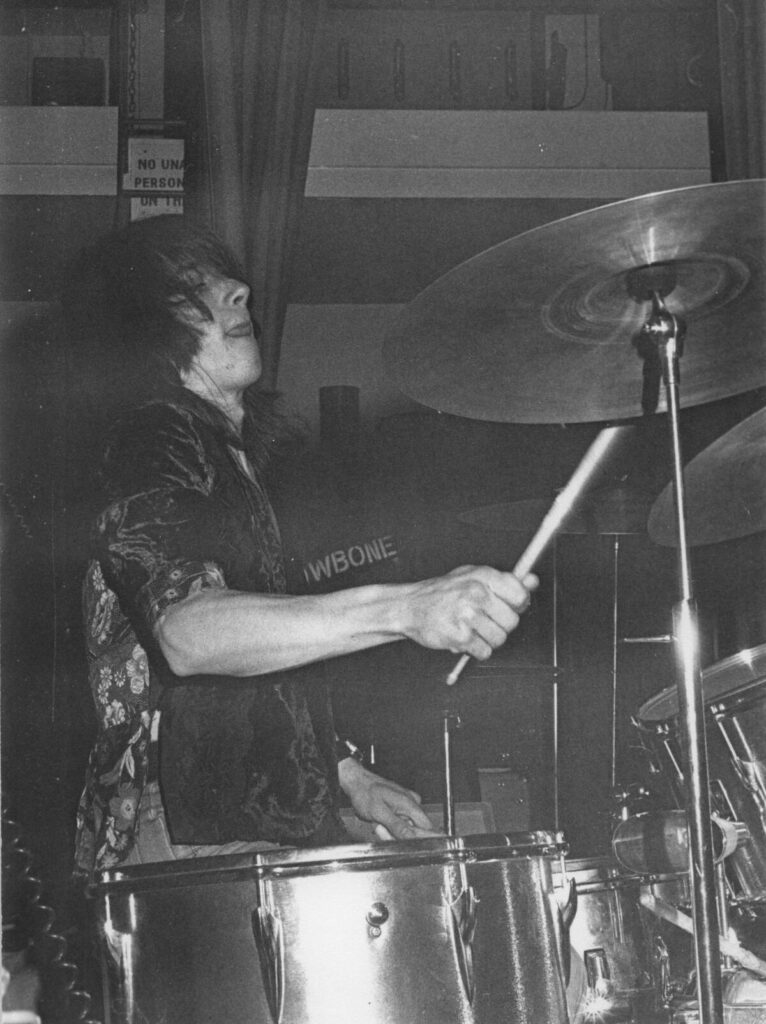

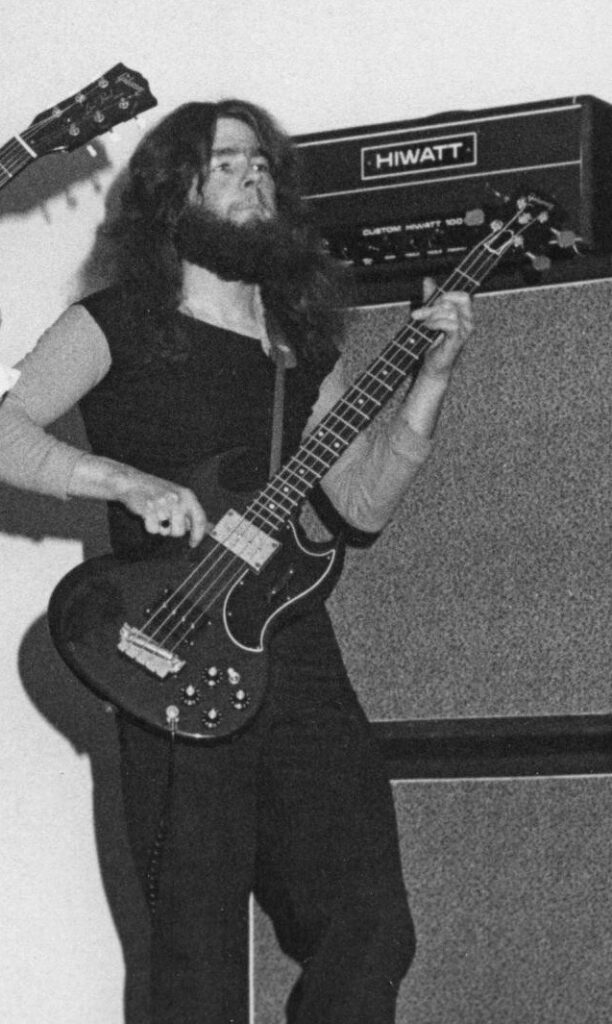

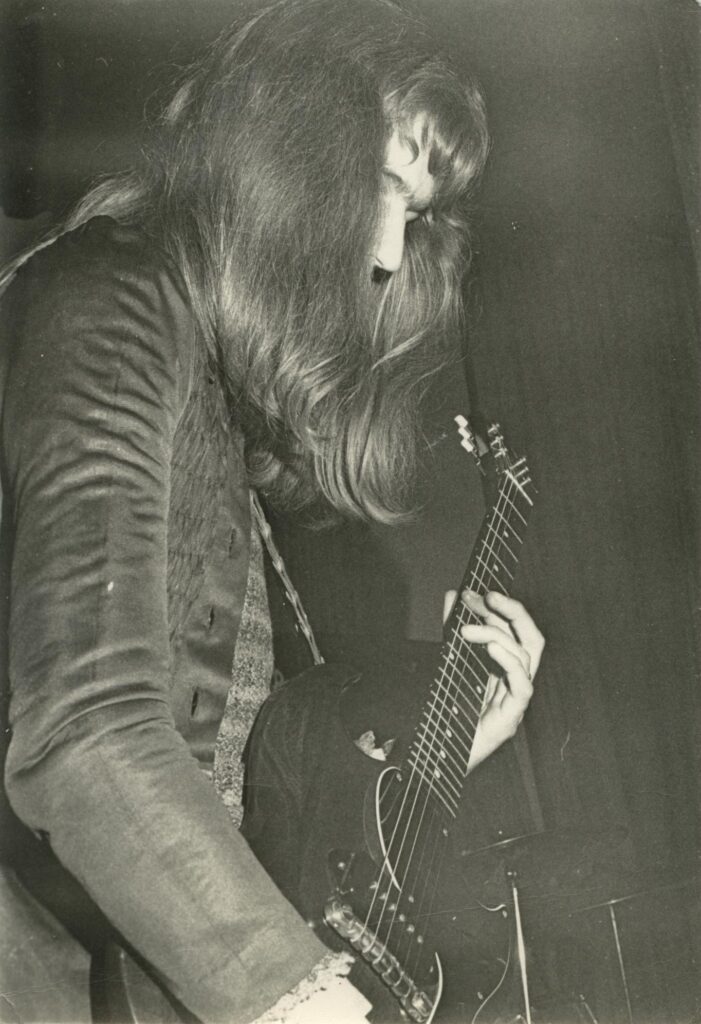

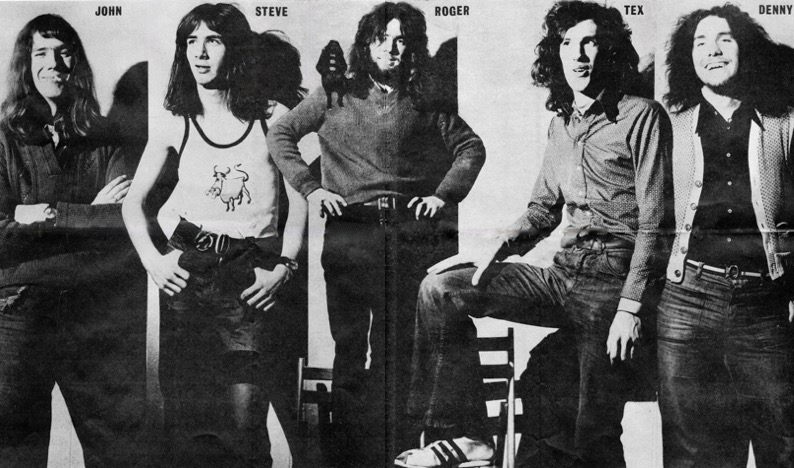

Think blues-rock pushed to the edge, proto-metal with teeth, and a touch of theatrical flair that never tips into parody. Castle Farm delivered the goods with a wild two-guitar front line. Gram “Tex” Benike lit things up with fiery slide work while John Aldrich played sharp… Holding it down were Steve “Spyder” Curphey (and later Roger) on bass, and Steve Traveller hammering the drums. Leading the charge was Denny Newman, whose voice had bite and soul, cutting through the mix with total conviction.

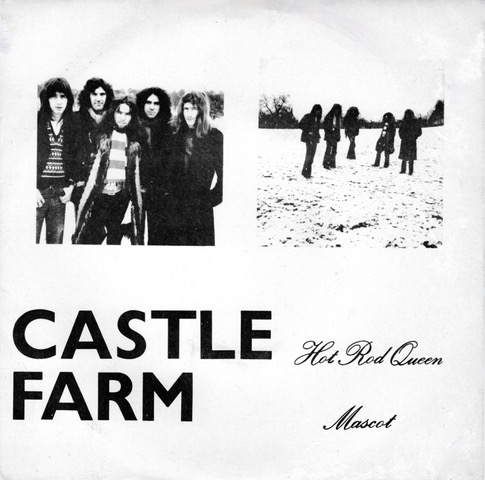

They shared stages with giants like Rory Gallagher, Deep Purple, and Atomic Rooster, leaving audiences stunned and venues occasionally in delightful disarray (just ask Slade’s manager, Chas Chandler!). Yet, like so many brilliant acts of their era, they got tangled in the industry’s darker side, their full album plans tragically shelved by the very folks meant to champion them. Their legendary ‘Hot-Rod Queen’ single, a self-funded gem, became a whispered myth among collectors.

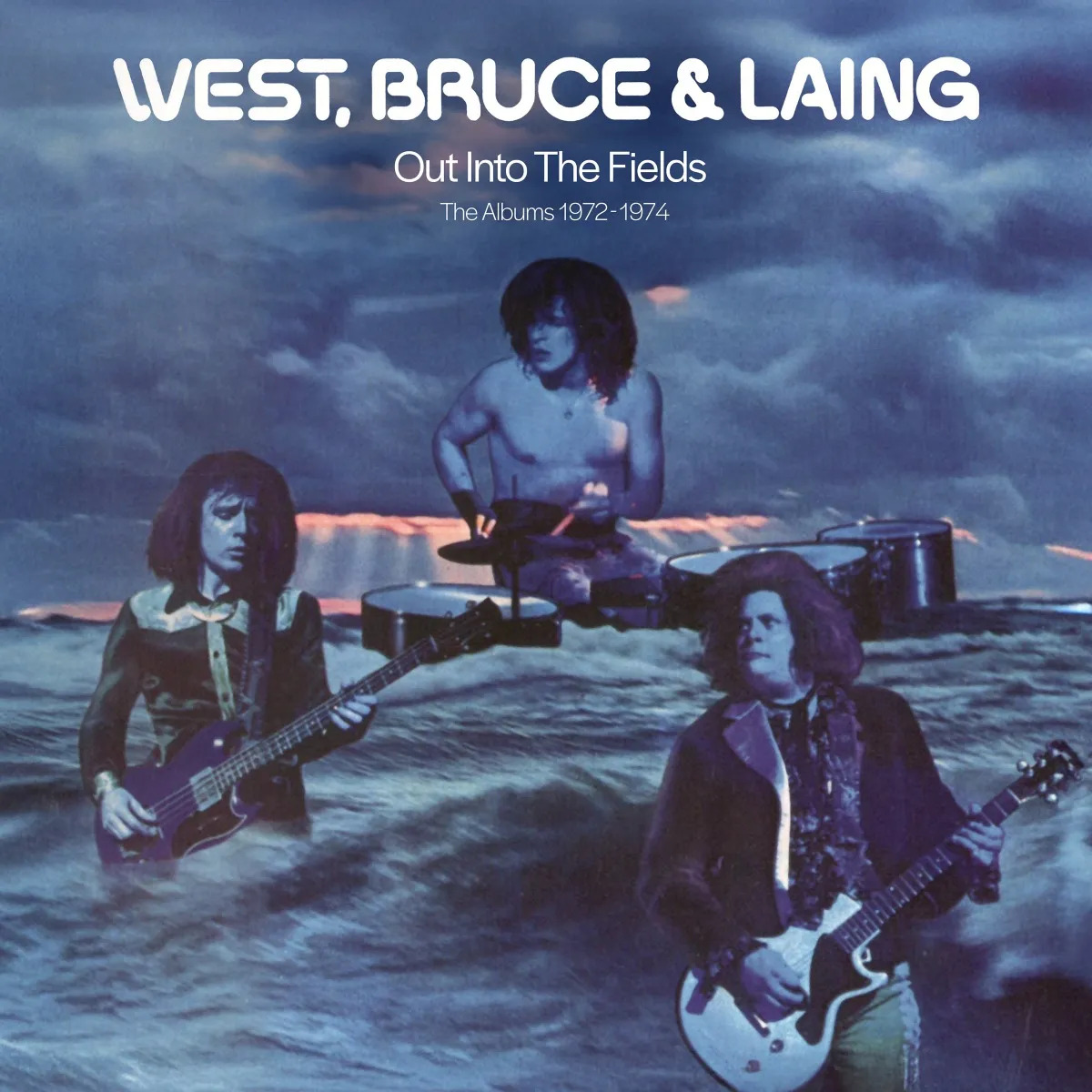

Still, great music has a way of surviving. Decades later, thanks to a bit of luck and a lot of love, Castle Farm’s lost studio recordings have resurfaced. Guerssen Records stepped in to give them a proper release. So drop the needle, crank it, and let Castle Farm finally take their rightful place in your record collection.

“Being a group that wanted to grab music by its throat and wring every ounce of feeling from our instruments.”

Fifteen years knee-deep in the underground muck, digging through bootleg haze, convinced I’d heard it all. Then bam! Something fresh bubbles up. After all this time, does it blow your mind that your music isn’t just seeing daylight but spinning worldwide on vinyl?

Steve Traveller: Yes, it sure does. For two reasons. Firstly, I was a big collector of vinyl, but in the middle of the 1980s vinyl died in the UK. I’d only bought a few pre-recorded cassettes in the 1970s, but when CDs came in it was a real game changer and I switched overnight.

Second, the vinyl album now being released by Guerssen Records could be seen as the one that should have been released after we signed a record deal in 1970. But we were conned by the record company and it didn’t happen (more on that later). So, it’s a huge thrill and a great honour to see our work finally getting the attention and favourable reception we always thought it deserved.

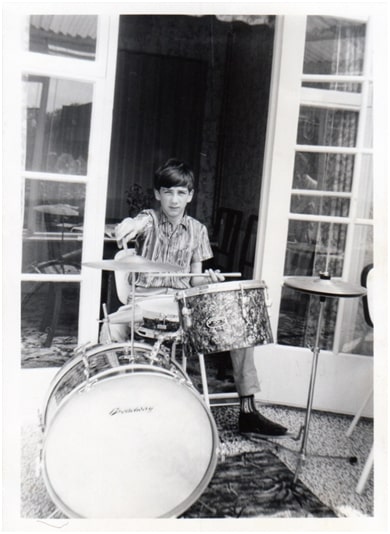

Let’s drop the needle on Side A. Where’d you grow up, and what was life like in those primordial years? Do you remember the first radio shockwave that hit your brain? The songs that flipped a switch? And what were the first singles you actually put your hard-earned cash down for?

I grew up in Ipswich and we moved to Essex when I was five years old. Mostly rural and well ordered in post-war England. I listened to the radio a lot, as we didn’t have a TV until I was about eight. In the late fifties and early sixties I was drawn to things like skiffle (Lonnie Donegan, The Vipers, Chris Barber), rock and roll, and particularly ‘Let There Be Drums’ by Sandy Nelson. Then it was Elvis, Cliff, Little Richard. Rock and roll was born, and I loved it. But when The Beatles, The Stones and especially The Kinks and The Who emerged, it was something else. I had The Beatles’ first album and The Rolling Stones ‘No. 2’ (I still have them), and I listened to them endlessly. In fact, that Stones album introduced me to the blues, which I’ve been hugely into ever since.

Was your town all grey factories and empty bus stops, or was there a secret undercurrent of freaks waiting to explode?

No, life was good. We had proper winters in England then, with proper snow and ice, and then beautiful long summers.

I think the coming of the psychedelic trend in 1966 and then the Summer of Love in 1967, along with what was happening musically on the West Coast of America, is when the explosion of hippies and freaks came around. It was a great time to witness very rapid musical development, with bands like Spirit, The Mothers, Chicago, Velvet Underground, etc., and I couldn’t get enough of it.

Before Castle Farm, what concerts did you see? Who made you think, Yeah, I need to be up there doing that?

My mum got tickets and took me and my younger brother to see The Beatles at the Gaumont Cinema in Ipswich in 1964. I was only 11, but that made the hairs stand up on the back of my neck and started me on a mission to see live bands. In those days you could see chart-toppers on multi-band tours at fairly local venues. So I saw bands like The Kinks, The Who, The Hollies, The Dave Clark Five, The Small Faces, Traffic and many others in small-town cinemas and theatres.

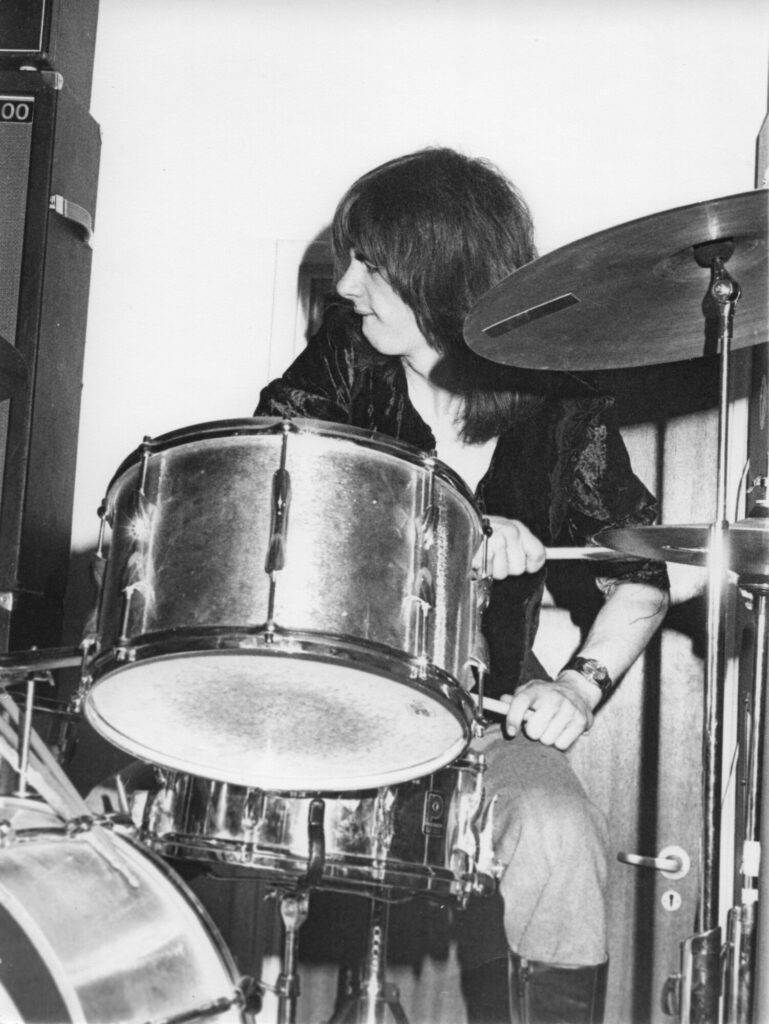

I had joined the Boy Scouts at 11, and they asked me if I’d like to be in the marching band, so I said yes, and that I’d like to play the bugle. But they were out of bugles, so they gave me a side drum instead. I went away and made a drum kit out of biscuit tins and some of my mum’s knitting needles and practised by playing along to records. Within a few months I was lead drummer in the Scouts’ marching band, as well as learning different styles and rudiments on my nascent drum kit at home.

What was the moment that locked it in: I’m gonna be a musician?

When I was 16 I went to see Cream’s farewell concert at the Royal Albert Hall in London. I had followed them since day one and admired their individual musicianship, appreciating how they were each masters of their own craft. I wanted to do what Ginger Baker was doing.

Also on that RAH bill were a new progressive band called Yes and a young band from Ireland called Taste. A wild-looking trio with Rory Gallagher up front, they really blew me away, and it was a real honour when Castle Farm got to support them a few years later. At a time when stagecraft was in short supply and too many bands were often self-indulgently spending way too long tuning up in front of the audience, Rory was a breath of fresh air. He would be in the bar, happily chatting to fans over a pint of Guinness or two, and then he would be up on stage behind the curtains tuning up briefly by ear with his bass player, Richard McCracken, before the curtains opened and he would fly to the front of the stage with a big thumbs up and “Y’Alright!” to the audience as he smashed into the opening riff of his first number. Absolutely no messing about. And he’s been one of my favourite guitarists ever since, despite his way too early passing.

Any pre-Castle Farm bands?

A couple of teenage meanderings, but none with any real talent or musical future.

Castle Farm: where’d the name come from?

Once we had the nucleus of the band we sat down and brainstormed a name for it. We all came up with names or just words, and I wrote them down in a list. As I read them through, Farm came after Castle, and one of the guys said, “That’s it, Castle Farm.” And that was it, done and dusted.

When did the band really take form? Give us the lineup rundown: who brought what to the table?

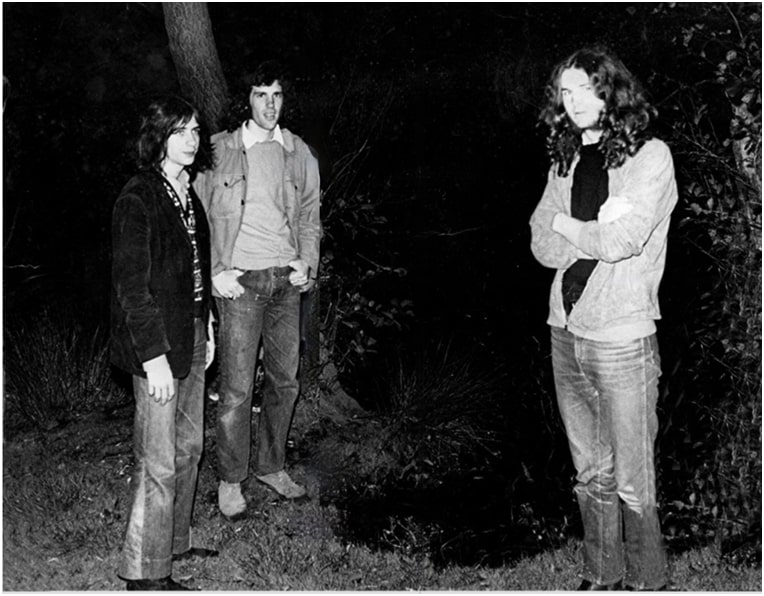

I had been in an amateurish little youth club band, doing mainly pop covers, but that was dissolving and I wanted to be in a band with some real talented musicians. We had no bass player, and one of the guitarists had let us down on a gig, so I put a postcard ad in the window of a local music shop looking for a guitarist and a bass player.

A couple of days later Gram “Tex” Benike (guitar) and Steve “Spyder” Curphey (bass) turned up on my doorstep. They were mates at a local technical college, and they really looked the part, proper long-haired rock band material. We arranged to have a jam in my parents’ front room, and it was a dream. Musically and personally, we just gelled. It was amazing, playing together, all on the same page and sharing our love for bands like Cream, Jimi Hendrix, Ten Years After, Taste, John Mayall, Fleetwood Mac, Velvet Underground, Chicago, and so on. We tried a few different singers, but it was really Denny Newman who brought a unique vocal contribution to the band and made our sound what you hear today.

Rehearsals: where did the magic happen? Some dingy backroom, a garage, a forgotten bunker? And how did you scrape together your first gear?

Initially we managed to find a hut in a kids’ adventure playground, run by a lovely lady called Amy Crockford. She particularly loved the song House of the Rising Sun, so she let us rehearse in the hut for free if we would play it and let her do the singing. She did a brilliant rendition, and all the kids would come inside from the playground to watch the performance. Later we used a little church hall to work up new material and rehearse, as it was always important to us to put on a great show wherever we played.

As far as gear was concerned, we borrowed money here and there and built it up gradually. In those days it was really important to carry around your own PA system. A lot of venues either did not have one or what they had was crap and sounded like a cat peeing in a tin lid, and that meant you had to have a van. We bought an old Bedford van with a sliding driver’s door which would often fall off onto the road if you pulled it back slightly too hard. Then we would all have to get out and hang the door back on. Eventually we bought a second-hand Transit bus from Badfinger, complete with a row of three aircraft seats, and that was real living.

Did you have a vision for the sound, or was it all instinct and volume?

One of our first pieces of PR talked about us “being a group that wanted to grab music by its throat and wring every ounce of feeling from our instruments.” We aimed to be exciting, yet versatile and down to earth, making music that was tough and honest, raw and emotional. We enjoyed using improvisation as we were all on the same page musically, but we used it in a controlled way to ensure that our songs really stood out and things did not just get messy.

Tell us about the influences: who lit the fire?

We drew from a wide range of individual and collective influences, as mentioned earlier, such as Cream, Jimi Hendrix, Ten Years After, Taste, John Mayall, Fleetwood Mac, Velvet Underground, and Chicago. But creating our own unique sound was really important to us, so apart from our own versions of some rock and blues standards such as Eddie Cochran’s ‘Summertime Blues’ and Dylan’s ‘Highway 61 Revisited,’ we kept to our own compositions.

Any gigs that still burn bright? What was the wildest?

One of the weirdest gigs we got was playing in an old stately home that had been derelict for about 30 years. A property developer had bought it with a view to turning it into refurbished apartments, but before work started on it he threw a huge party in the ballroom with snooty guests all wearing psychedelic-coloured kaftans and eating very strange macrobiotic food. I am not sure we provided the most appropriate music. He probably really needed a string quartet to play in the background, but we were booked to play for £50 (about £1,000 in today’s money), the most we ever got for one gig. But nobody complained, and we all went away very happy.

Gigs at the Marquee and Temple Club in London were always great fun, and I remember supporting Atomic Rooster at the Cliffs Pavilion in Southend-on-Sea, when the band all came to watch us from the wings during our performance. So we must have been doing something right. We also had a fortnightly residency at a club in Southend and a new band called Dr. Feelgood supported us there a couple of times.

A view from Gram “Tex” Benike, taken from a previous interview:

Just read this interview about Castle Farm. I was in that band along with Steve Traveller, Steve “Spyder” Curphey, and Denny Newman (this is Gram “Tex” Benike from Phoenix, AZ). The Basildon Arts Lab I remember… total chaos at the end. We were banned from ever playing there again because a bunch of seats got destroyed by fans during our ‘Summertime Blues’ finale. I remember a shocked and white-faced Chas Chandler (Slade’s manager) walking into our dressing room after our show, asking if our gigs were always like that. “Usually” was our reply. Then Slade came on. They were on the rise but not superstars yet, but really loud. Great memories from this band. Fun times back then. Best, Tex.

Did you ever get tangled in the industry machine, or was it all pure DIY madness?

We did get tangled in the industry machine. In fact, we were very royally conned. We put ourselves in for what was effectively a talent contest for aspiring bands, held in a pub in London, with around a dozen bands playing two or three songs each, with what were considered the top two bands being signed to a recording contract. Trouble was, the record company was run by a guy called Pat Meehan, who had been Don Arden’s right-hand man. Arden (Ozzy Osbourne’s father-in-law) had screwed the Small Faces and others out of a lot of money, so Meehan had had some good training. He later went on to swindle Black Sabbath out of performance payments and property (source: Wikipedia).

For us, it meant the signing of a worthless recording contract designed to put us on the shelf and keep us out of the way of bands like Sabbath that the company was working on.

What led to the recording of ‘Hot Rod Queen’ / ‘Mascot’ in ’71? Where was it cut, and what is the story behind those tracks?

Despite being shafted by Meehan, we had a great following, and we knew that we could sell records. So we decided to put out our own self-funded single, one of the very first independent records to be released. The two tracks on the single were recorded at Tangerine Studios in London (Rory Gallagher had recorded his album Deuce there) on 15 February 1972 and mixed down on 22 February 1972.

We had met a guy called Hedley Leyton, who had worked with John Hiseman’s Colosseum on their Live album, and he helped us produce it.

How many copies were originally pressed? Did you send any to major labels? Did you get any airplay?

We had 2,000 copies pressed, distributed them through local record shops, and they sold out within a few weeks.

I sent a copy to John Peel, who played it on his radio show, but unfortunately he did not play it on an endless loop as he did later with The Undertones’ ‘Teenage Kicks.’ We also sent it to Island and a couple of other labels, but at the time they were sticking to their knitting.

Guerssen recently unleashed a stash of unreleased 1971 to 1972 recordings. What is hiding in the vault?

I have a few reel-to-reel tapes of some live performances that I might try to dust off one day, but I doubt if the quality would be up to the standard we would like to put out, to be honest.

Was there ever a full album plan? And where were those recordings collecting dust all these years?

There was an album plan when we signed to PandA Records, and we subsequently made the recordings you will hear on the Guerssen album once we had managed to get out of that contract. Those recordings existed on the vinyl single, a couple of acetates, and a cassette tape that had miraculously been saved over the years, the original master tapes having long been lost.

Around 2000, someone told me that ‘Hot-Rod Queen’ had been included on a compilation CD, and I was initially quite chuffed that the song had made it that far. Mascot was put on a subsequent CD, but of course both tracks had been simply lifted (without permission) from a copy of the single. So I got them taken down from the downloading and streaming sites on the basis that the company behind the CDs had no rights to use them, and then asked my son Paul (a sound producer and engineer) to tidy up all the recorded tracks I had as best as he could. We had an album’s worth of tracks, so I put them onto the internet via a distribution platform.

“We never really got a chance with a reputable label”

You shared stages with Rory Gallagher, Deep Purple, Atomic Rooster, Savoy Brown, Climax Blues Band, Quintessence. The heavy hitters. What the hell happened that kept the album from getting done?

After the experience with the aborted record deal, we never really got a chance with a reputable label. The industry was alive with con artistes and the market was hugely competitive in the UK, which meant so many cracking bands never really saw the light of day in the way they should have, and so many dodgy managers and agents built helicopter pads and swimming pools on their illegally funded properties.

How long did Castle Farm last, and what ended it? A glorious crash and burn or a slow fade into the ether?

After three years together we decided to close our doors. We all needed to go and make a decent living. Gram “Tex” Benike went back to his native US, and only Denny Newman made music his long-term career, releasing numerous excellent albums, with his blues band backing Mick Taylor on his tours, and building himself a well-deserved reputation as “the best kept secret in British blues.”

Of course, we have always remained great friends and kept in touch, and we got to play together over the years when we were all in the UK at the same time. The last time was in April 2017, when we put on a reunion concert for all our old friends and fans.

Now that people are finally hearing this stuff, what’s that feel like?

Naturally, it’s fantastic to know that our music is being appreciated, and the reviews are good. The vinyl issue is really the icing on the cake. It’s just a shame that there are only three of us around now to see it happen.

When Castle Farm was active in the early 1970s we used to jokingly claim to be “world-famous from Mile End (East London) to Southend (Essex).” Since our music was put on the digital platforms we now have listeners in over 1,200 cities in 70 countries, just on Spotify alone, and the United States alone accounts for around a third of our listeners. Great stuff.

Do you remember your typical setlist? And what gear and amps powered the storm?

We always went out of our way to put on a wild and entertaining show, where people could really let their hair down. Lunatic typifies that approach, and to me that song pre-dates punk by at least six years. But as well as rocking out, we also made sure we found room for a bit of variety, bringing in a mellow, jazzy feel with ‘All In A Year, All In A Day,’ a bit of a folky vibe with ‘You Go Your Way, I’ll Go Mine,’ and a heavy blues with ‘I’ve Been Dreaming.’ And our slowed down, crunching version of ‘Summertime Blues’ always brought the house down at the end of the set.

After the dust settled, what happened to you and the rest of the band? Did anyone keep playing, or did life swallow it all up?

We all kept playing to some degree; open mic nights and things like that, and when Denny Newman was playing with his band over here, we would often just get up and jam. None of us lost our affinity with music, and it nurtured our mutual bond all the way through the years.

What’s life like now? Still connected to music, or is that chapter closed?

I have loved music since I was a kid, so it’s still a very important part of my life. I’m also very proud of the fact that my son Paul first picked up my drumsticks at around the age of eight, ultimately overtaking me in terms of technical prowess by the time he was 15. Watching him develop his playing skills, as well as in music recording and sound production, has kept me very involved in music generally.

A couple of videos to demonstrate some of Paul’s work with his band Edenflaw:

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Thanks Klemen, for letting me waffle on a bit about the band. It’s been real fun reminiscing, and I hope my contribution stirs up some good nostalgic reflections of a wonderful period in British music for you and your visitors to It’s Psychedelic Baby Magazine. It’s only rock’n’roll, but I like it.

I’m now very honoured to be able to go fishing at a nearby trout fishery, owned by one of my all-time favourite musical heroes.

Klemen Breznikar

Guerssen Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / X / Bandcamp / YouTube