Nirvana: The Visionary Duo Who Redefined British Psychedelia, Captured in a New Box Set

Before the mythology of 1960s London hardened into its familiar legends, two young musicians were quietly reshaping the city’s musical imagination.

Patrick Campbell-Lyons, from Ireland, and Alex Spyropoulos, from Greece, met by chance in 1966 and began crafting songs that moved far beyond the boundaries of pop. Their music blended baroque arrangements, surreal storytelling, theatrical whimsy, and an instinctive understanding of mood. It remains one of the most distinctive bodies of work from the era.

Their legacy is now illuminated with unmatched clarity in ‘The Show Must Go On: The Complete Collection,’ a major new release from Madfish. Presented as a twelve disc set, it gathers all eight of Nirvana’s studio albums with newly remastered audio along with three discs of outtakes, demos, and rarities. Among them are treasures long sought by collectors, including the 1971 Vertigo label single ‘The Saddest Day of My Life’ and a rare version of ‘Everyone Should Fly a Kite.’ The set arrives housed in a deluxe lift-off lid box with each CD in a mini LP sleeve.

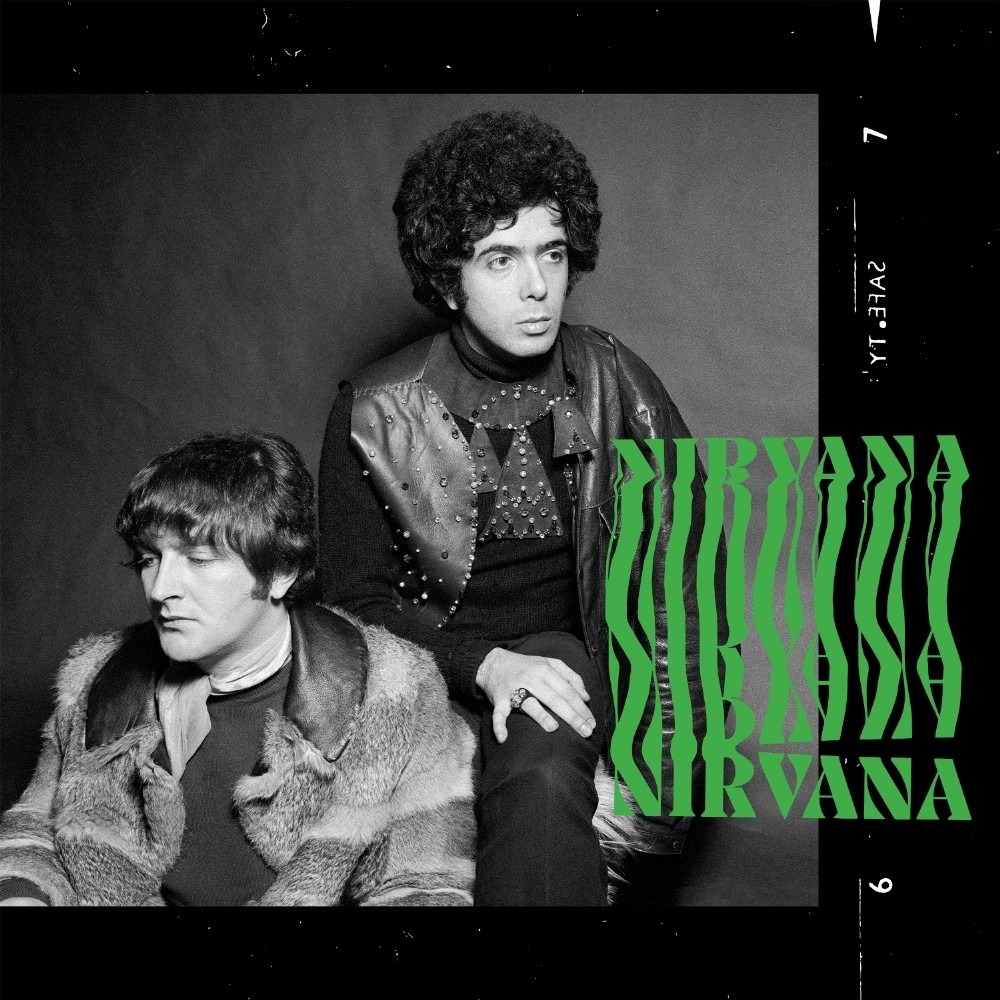

A ninety-page hardback book accompanies the music and provides the most complete portrait of Nirvana ever assembled. Through new interviews with Campbell-Lyons and Spyropoulos, along with previously unseen photographs by Gered Mankowitz, the book reveals the texture of their world. Campbell-Lyons recalls early sessions with a twenty-six-piece orchestra performing arrangements by Syd Dale whom he describes as a gentleman and a genius. He remembers how their demos sounded as if they came from another planet compared with the music echoing through the walls of Island Records. He speaks of the Celtic and Hellenic influences that shaped their songwriting and the sense of oceanic drift that appears again and again in their melodies.

‘The Show Must Go On’ captures a partnership that created its own imaginative universe and whose work continues to speak across generations. Far more than a retrospective, it is a vivid show of how two outsiders helped expand the possibilities of British music.

“Precious were those days of catching lightning in a bottle.”

The box set describes Nirvana’s sound as moving “beyond the confines of 1960s pop into baroque, psych and proto-Prog territory.” Could you elaborate on the creative environment, collaborative process, and initial musical tools like the Revox etc. that defined your early demoing sessions and set the foundation for this unique sound?

Patrick Campbell Lyons: Right from the start we knew we had written at least six very good songs. We knew how we wanted to demo them on the workhorse that was Revox. We also had a few crazy gadgets and some trippy percussion, some tambourines and maracas inside several shoeboxes, using only brushes. I had an autoharp for string effects and some vampers that we used with effects to create a drone brassy sound. We hit various objects in the small garret-sized room where we worked, except each other. We were having so much fun and were high on the creative energy. We worked from two in the afternoon to ten at night, then we went out to eat, drink and visit clubs that we both knew to be very hospitable with discreet management and an international array of beautiful people. Then we slept somewhere and started work again the next day. This went on for four months, six days a week. Sundays were our own to do as we pleased.

When we created, we had no rules and did not follow trends that were happening. We both used the word variety often to describe the things we developed and never allowed anyone in the recording process, not producers or record label people, to drop a song because they thought it would not work on an album. Examples include ‘Everybody Loves the Clown’ from 1999, ‘Aline Cheri’ and ‘We Can Help You’.

When we did start recording for real, Chris Blackwell, our mentor and founder of Island Records, gave us free rein for the three-album deal. He paid us a weekly retainer equal to that of other bands signed to his visionary, innovative and independent label. Island was the first and only true independent record company and was copied by so many others, although they always felt fake until Dave Robinson came along with Stiff much later, which had a whiff of authenticity. Chris covered all our recording costs generously.

Alex and I felt foreign in London. We were never part of the London scene, and that made us try harder to make it. It gave us an edge. Together we were a creative force, and we used that confidence to follow the dream religiously. So when Chris Blackwell asked, “What do you guys want? To be a band, rehearse and go on the road, or do you want to work with an orchestra?” we knew the answer before he finished the question. He was a visionary, and we were the dreamers.

We knew when we were writing our songs how they should sound, a thirty-piece orchestra with arrangements by Salvador Dali. Yes, and yes. Chris said we should meet Syd Dale, and that we would get on well. I looked at Alex. Both of their names were already perfectly interlocked. I was blown away.

We took a train to Beckenham in Kent, I think, and the Maestro swept us away to his home. That is how Nirvana became a tour de force. Syd was a genius arranger and as crazy as we were. Simon Simopath was the result of our creative time with him working on his arrangements of our songs. Precious were those days of catching lightning in a bottle.

When we got to the real business in Pye Studios and started recording, Syd brought all his magic and flair to the occasion. He was a joy to work with and be around, and his orchestras were always smiling.

The story of ‘Simon Simopath’ was done and dusted with magic in five days. Three songs a day, two run-throughs with guide vocals in the cans for all musicians and the three girl backing vocalists. Two takes maximum for the backing track, and Bob’s your uncle. In the afternoon we did our vocals, and in the evening we mixed to get the finished masters. Monday to Friday, all wrapped up. How? Because everyone knew exactly what they were doing, and they played what Syd had written for them. His arrangements were diamond dots, and the vocals had a great bed on which to perform.

The brass and string players were the best to be found in London, and they worked with Syd all the time. I would like to give a special name check to the band and rhythm section:

Alan Hawkshaw, piano and organ

Alan Parker, guitars

Herbie Flowers, bass and double bass

Clem Cattini, drums

Barry Morgan, drums

Frank Ricotti, percussion

Girl singers Sue and Sunny and Leslie Duncan

Chris Blackwell handled production with engineer Brian Humphries, and Muff Winwood was in A&R. Everyone involved had something special to give, and the result is an album that follows no formula or trend. It is still relevant today, fifty-five years later. In many ways it is timeless, and the quality of the recording, whether you hear it on the radio or online today, is amazing.

‘The Story of Simon Simopath’ is noted as arguably one of the very first “concept” albums. Can you discuss the narrative development process for the album, including the original working title for the main character and how the songs ultimately came together to support the story?

I do believe so! We were not aware of this British rock concept album idea at all until journalists started creating that dialogue later on. However, the first album I heard that I thought was coming from a theatrically trippy, happy band with great tunes and a stoned concept was ‘Playback’ by The Apple Tree Theatre from LA, two brothers, the Boylans, on Verve Records. It became a big-time favourite of mine, and I still play it today. Sometimes I think they were ploughing the same furrow as us at the same time— they in the west coast sunshine of California, we in rainy, damp London. ‘Playback’ was released a year after ‘Simon Simopath’.

An interesting thought: when I was working on the storyline for our pantomime fantasy for grown-ups, as I described the album, Simon was originally Simon Psychopath. It was only when we wrote the songs ‘We Can Help You’ and ‘1999’ that he became Simopath, and we went with it. Not many people know that.

This definitive 12-CD compendium encompasses the complete studio recordings of Nirvana, all with newly remastered audio. Beyond the audio, what non-musical elements or memories…such as the photo sessions with Gered Mankowitz…do you feel this box set successfully recaptures, and how did Nirvana’s position outside the main London scene contribute to the distinctiveness of your music?

For me personally, it was seeing a photograph that Gered Mankowitz took of me cradling a crucifix while looking at the camera and beyond. We did a number of studio sessions with the fashion photographer, in what was his first foray into show business. Chris Blackwell knew him. Gered became our go-to man. He found something in our musical DNA that he captured through the lens of a very large, unusual camera on a massive tripod. He disappeared underneath a cloak that covered the camera when he made his shots, accompanied by a loud flash. The world of pop.

As you can see in the book, even at such a young age, he had the magic. Around that same time, he worked with the Stones, Hendrix, Small Faces, and soon everyone wanted him. The crucifix—I have no idea where it came from. Ironically, at that time I had turned my back on the Catholic faith, which had been my church of indoctrination since birth. Thankfully, God found me again in a different spiritual place.

It happened without us trying to be part of any scene that was happening at the time. Our elusiveness made us interesting. A good example is that I recall going into the Island office many times when we first signed with them. David Betteridge, one of the original founders with Chris, had his desk there, and he greeted us with, “Hi, it’s Nirvana!” That kind of stuck, and others picked up on it.

We were really a duo, to put it simply. Nirvana was our calling card, and our songs were so different from everyone else’s. When we used the record cassette player in the music hangout room, our demos sounded from a different planet compared to what Art or Guy Stevens, Spooky Tooth, Traffic, Free, and sometimes the Smoke were playing. They even covered our ‘Girl on the Park’ after hearing the song there.

Another difference was that all these bands were from the counties and were somewhat in awe of the capital, I felt. They met at night in pubs like The Ship on Wardour Street before a gig and at the Speakeasy afterward. Breakfast at any hour at the Ace Cafe was a shared experience for many.

The Island Pink Label family was a truly unique experience. Elsa, Chris’s PA, and Penny Hanson, who organized and kept our house in order, were invaluable to the journey we were all on. So was Chris Peers, who helped get the finished records onto the BBC.

We were different because we were from Greece and Ireland. Our accents sounded distinct, creating a Celtic-Hellenic mix of ancient ground, water, blood, and myth, always accompanied by the sound and music of the ocean. That was and still is the resilience of the original Nirvana. Our songs and the way they still connect six decades later speak for themselves.

I was never a hi-fi audio or great-gear music creator—excuse the pun—when it comes to listening to my music or anyone else’s, even to this day. In those early years, I had a record player deck with a couple of small extension speakers. Over the decades, my brain has become tuned to four tracks, minimalistic, letting my imagination run free. I listen to music on headphones, to radio stations from everywhere and anywhere across the globe. Everything and anything—it’s all out there, and we are a part of that.

This Nirvana CD box set release, ‘The Show Must Go On,’ is part of our musical legacy, as is the vinyl box set ‘Song Life,’ released some years ago on Madfish. Alex and I were always happy that if something we wrote and recorded sounded good on the radio, that was the gravy—a job well done, move on.

I rarely listen to what I have written, recorded, and released from the past, including Nirvana, except for projects such as this release, which is a very pleasing experience, as was the vinyl box set and the Island Universal CD set a few years earlier. I do listen to new songs that I am working on…home and basic studio demos, sketches of guitar and voice, and that is enough for now.

God’s blessing for the gift of songwriting and for being Irish means always being a new face in a new place.

Your collaboration with legendary session musicians like Clem Cattini, Alan Parker, and Herbie Flowers is highlighted. Given that Syd Dale’s arrangements were meticulously scored for the rhythm section and orchestra, how did the expertise of these seasoned professionals contribute to the polished, final sound of the studio recordings?

There were six players in the rhythm section: Clem Cattini, Herbie Flowers, Eric Ford, Alan Hawkshaw, Alan Parker, and Frank Riccotti. A twenty-six-piece string and brass orchestra, including timpani and harp, also participated, and everyone played the dots—what Syd Dale had written as the arrangement, the score for each of the three songs in the session.

So the short answer is no. If Syd felt a tempo or tuning needed fixing, he used his conducting baton or a discreet word. After our initial sessions at Syd’s home, what he then wrote was, in a way, set in stone. I have said it before: Syd Dale was the man for us and for many other songwriters of that era. He is in our music like an invisible cloak, a gentleman and a genius.

‘All Of Us’ is described as a “psychedelic baroque pop tour de force akin to the Zombies’ equally brilliant ‘Odessey And Oracle’.” You mention not having listened to ‘Odessey And Oracle,’ but based on your personal record collection from that era, which included albums by Love, Frank Zappa, and Tim Buckley, what artistic influences and sensibilities do you feel best explain the unique sound of ‘All Of Us’ and the music you were creating at that time?

I never met the band or any of the members, nor did I see them live. They were formed and on the road, I think, about two years before our Island Nirvana journey. To be honest, I have never listened to the album in question. One of those things, I suppose. I know they had a hit with ‘She’s Not There’ because it was on the radio and still is. That was it. There is no connection or comment I can make about this album and any of ours at Island.

If I tell you that at that time, from the mid-60s to early 70s, I owned about fifteen albums that I carried around and played repeatedly, it might give some context. These included three Mose Allison albums—’Mose Alive,’ ‘Swinging Machine,’ and ‘Wild Man on the Loose’—Jimmy Reed at Carnegie Hall, Ravi Shankar’s ‘Portrait of a Genius,’ Love ‘Forever Changes,’ Frank Zappa’s ‘Reuben and the Jets,’ ‘Bo Diddley is a Gun Slinger,’ ‘Another Side of Rick’ by Rick Nelson, Charles Mingus ‘Oh Yeah,’ The Everly Brothers ‘Sing,’ Bob Dylan’s ‘Highway 61 Revisited’ and ‘Bringing It All Back Home,’ Tim Buckley’s ‘Happy Sad,’ Paul Butterfield Blues Band, and The Doors’ ‘Waiting for the Sun’.

The collection notes the inclusion of your 1971 Vertigo label single, ‘The Saddest Day of My Life,’ and an alternative version of the 1973 solo single, ‘Everyone Should Fly A Kite.’ Could you discuss the personal and professional challenges you faced during the period between the Island Records years and the recording of your Vertigo album, ‘Local Anaesthetic,’ and how those experiences influenced the lyrical themes and emotional tone of tracks like ‘The Saddest Day of My Life’?

I was proud of the songs we had written and recorded on Island Records. I felt elevated, as did Alex, from the effort we had put into everything. It all felt good for the future as Alex and I agreed to have some time apart. I think he went to Greece for that summer. I had also asked him if he was okay with my using the Nirvana name if I recorded a new album, which was fine with him.

I was riding an emotional rollercoaster and waiting for inspiration. I then started to have days and weeks where I would drop down into feelings of selfishness and anxiety, thinking that I had neglected those close to me, my real family and friends. I started to binge on amphetamines and booze. I was in a bad place for a while. With the help and advice of Johnny Franz, a producer at Philips Phonogram who I had been introduced to socially, I got back on track. He was producing Scott Walker and invited me a number of times to the studio at Marble Arch to watch him working and learn something. He also invited me to his home to meet his wife Moira and eat together. He was class.

Dick Leahy, who was in A&R at the new record label Vertigo, asked me if I would be interested in doing a Nirvana album for them. I was, but I said I needed two or three months to get myself together and write some new songs. That is what happened, thank God. I started recording ‘Local Anaesthetic,’ Nirvana’s fourth album, two months later.

The tracks you ask about in your question for me to elaborate on, ‘Saddest Day of My Life’ and ‘Everybody Should Fly a Kite,’ each have a special meaning. The first is about the abuse of alcohol and pills and the wake-up call that came with it. The other is about being free to say and express what you feel, whenever and wherever, and to never be afraid to improvise with music, life, and creativity.

I recorded another Nirvana album, ‘Songs of Love and Praise,’ on Philips Phonogram later the next year. Alex Spyropoulos and I then started working again on our musical ‘Secrets,’ which we recorded ourselves. It was a musical milestone in our amazing journey together. We also wrote and recorded another Nirvana album, ‘Orange and Blue,’ in the 1980s. All the albums mentioned in this answer are included in this box set, ‘The Show Must Go On’.

The compilation highlights the contributions of producers and sonic wizards like Jimmy Miller, Tony Visconti, and Muff Winwood. Can you describe the creative atmosphere at Island Records’ 155 Oxford Street office, and how the distinct personalities and musical input of American producer Jimmy Miller and songwriter/arranger Tony Visconti manifested on the tracks you worked on, such as the flute on ‘The Show Must Go On’ or the drums on ‘Tiny Goddess’?

Over fifty years later, and knowing that between them they have produced some of the great classic rock albums of all time: the Rolling Stones, Motörhead, Bowie, Marc Bolan, Gentle Giant, Iggy Pop, and the Andy Warhol scene… I feel honoured and very fortunate to have been there when they showed up at 155 Oxford Street, Island Records’ first home, and to have had them involved in our recordings.

Chris Blackwell knew Jimmy, an American musician and producer, and brought him to London, where the action was happening. Denny Cordell, who had a record company office opposite Island named Regal Zonophone and was on the same trajectory as Chris, brought Tony Visconti, a songwriter and arranger from New York. Jimmy was a very gregarious character and, as we were soon to find out, a great drummer. Tony was kind of shy and laid back and let his musical knowledge do the business.

The whole place was a hotbed of creativity and shared talent, with Chris and Muff Winwood motivating the energy. Tony played flute on ‘The Show Must Go On’ and arranged some cello parts for a couple of tracks that we co-produced. The drum tracks that Jimmy played on Tiny Goddess, including Omnibus, at Olympic Studios are driving and solid as stone. When I recently heard ‘The Show Must Go On’ box set bonus material CD, I was transported to a magical time in my memory treasure box.

The box set is titled ‘The Show Must Go On,’ which is also the name of an instrumental track from your second album. What does this title personally signify about Nirvana’s legacy and endurance, and what does the featured inclusion of the bouzouki on that track represent about your “Celtic-Hellenic” cultural background?

The record company suggested the title to us. It is the title of an instrumental track from our second album. We both liked the idea and went with it enthusiastically.

I feel that it says a lot about us. Having a bouzouki as the featured instrument is a cultural connection, I would like to think—mandolin in my Ceilidh Ireland background, and Alex having that sound rooted in his DNA. Sometimes you do not need words to send a message.

Your reference to another band who used the same name twenty-five years later, and our necessary litigation to protect our name and its use, I think is irrelevant. To be straight with you, Klemen, a thought just came to me as I write now. ‘The Show Must Go On’ is special because it is another way of saying…

Your 1968 track ‘All Of Us’ was used as the theme tune for the cult movie The Touchables. Can you recount the specific moment at the Island Records office that led to director Robert Freeman discovering the track, and what the experience of finishing the song at Pye Studios with the director, producer Jimmy Miller, and the film’s actresses was like?

Being in the right place on the right day, good karma! The flimsy soundproofing of office walls at Island made Fridays always full of action. Everyone came there; it was a very social atmosphere. The bands, management, and creatives all mingled. You could hear everyone’s music and chit chat, as the walls were just ceiling-high partitions.

Cut to the chase: film company people were in Chris’s office with him—Stevie Winwood and Traffic/Spencer Davis, who had a single released on a popular movie of the day called ‘Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush’ on Twentieth Century Fox, whose offices were a short walk away in Soho Square. Director Robert Freeman and his team were leaving Chris, having not heard anything that worked for their new project, The Touchables. From the corridor, they heard Alex and me playing a demo version of ‘All of Us’ to producer Jimmy Miller in one of the rooms. Someone said, “What’s that song?” That was it.

From Ealing Broadway to Hollywood and Vine, we finished our work on it. A few weeks later, we were in Pye Studios with everyone involved: director Bob, producer Jimmy Miller, and the movie’s three lead actresses, who were going to sing an overdub track on our version. Good-looking girls with perfect 60s voices. Hear it in the here and now: a naked, mellow vibe from fifty-five years ago, outtakes and all.

We had to find a place to be on our own! I have seen it on the big screen, and it really is a true 60s British London classic. The title song was written and recorded by a Greek and an Irishman. The Beatles and Otis Redding feature on the film soundtrack LP release.

This is described as a “limited edition, one-time pressing.” What key takeaway or overall impression do you hope listeners, particularly the new, younger audience will gain from experiencing the complete scope of Nirvana’s music and the story of your creative journey through this box set?

I hope that the new, younger listeners will find a kaleidoscope of sounds, images, and moments of magic that we both experienced daily while we lived, worked, played, and recorded our songs at the centre of a unique world…60s London, and the creative journeys that followed for both of us into the next century. ‘The Show Must Go On.’ It did. It still does, and it will, until the joint stops jumpin’.

Klemen Breznikar

Madfish Music Website

Nirvana | Interview | Alex Spyropoulos

Nirvana | Interview | ‘Songlife’ The Vinyl Box Set 1967-1972

Nirvana | Patrick Campbell-Lyons | Interview