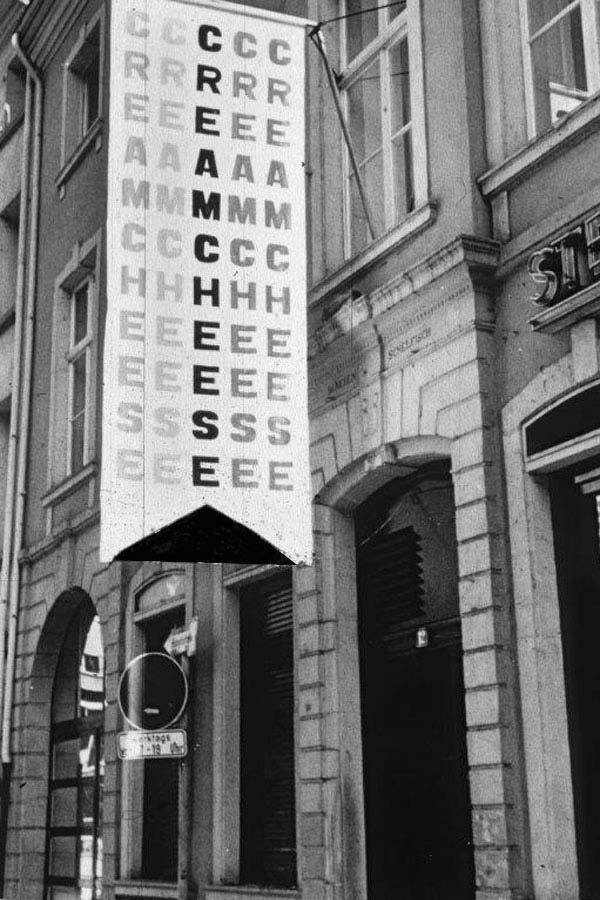

Creamcheese: LSD, Stroboscope, and the Rock Revolution | How Düsseldorf Invented the Music Revolution!

Creamcheese in Düsseldorf is undoubtedly one of the forgotten phenomena and places in the history of rock, culture, and art.

This makes its history all the more fascinating from today’s perspective, as the previously unknown story of Creamcheese also serves to correct contemporary views of psychedelic and krautrock, as well as the entire rock revolution of the 1960s and 1970s. Much of what has been publicized in recent years in the hope of profitable marketing has simply proven to be inaccurate. Even the city of Düsseldorf has demonstrated an inability to manage its own cultural heritage.

In order to properly understand the fascinating rise of this iconic club, terms such as krautrock, psychedelic rock, garage rock, and electronic music must be considered in their original context. Neologisms such as heavy psych, stoner metal, or garage psych should be recognized as meaningless but fashionable buzzwords that did not exist in the mid-1960s. This distinction is essential for appreciating the innovative achievement of Creamcheese. It also explains why Creamcheese was largely overlooked during the Kraut and Psych Rock revival of the last decade, a revival that amounted to little more than superficial marketing with no real interest in the original meaning of these terms. The significance of Creamcheese becomes even clearer in this context, as it was the only psychedelic club in the world to operate for more than four decades.

At the end of 1966, the first albums were released that propagated a new underground movement and introduced the term “psychedelic” to a wider audience. Considering that the Creamcheese concept had already been conceived that year but did not open until July 1967, as its interior and light show still had to be built, it is striking from today’s perspective how closely Creamcheese aligned with the pulse of the times. London’s UFO Club is rightly regarded as the nucleus of the British underground, presenting the first performances by bands such as Pink Floyd and Soft Machine at the end of 1966, but it only operated in one other club on weekends. In contrast, Creamcheese was an independent venue open six days a week.

So let us travel back to the mid-1960s, to the emerging hippie movement and the Summer of Love, climb into the “Yellow Submarine,” and remember that even Heinz Edelmann, the art director of the film of the same name, studied at the Düsseldorf Art Academy and later taught at the Düsseldorf University of Applied Sciences.

The connection between art and music has always been closely interwoven in the cultural metropolis of Düsseldorf. Another parallel to the British underground can be found in fashion, as Düsseldorf was considered “Little Paris” from an early stage. These conditions created a unique breeding ground for a new youth culture that sought to come to terms with the Nazi legacy of its parents’ generation in post-war Germany in order to shape a modern and free future. Creamcheese also nurtured the first seeds of Krautrock, which flourished in the early 1970s. Early bands such as Amon Düül, Tangerine Dream, Can, Guru Guru, and Floh De Cologne performed at Creamcheese from 1968 onwards. Kraftwerk also gave one of their very first concerts at the Düsseldorf club in 1970.

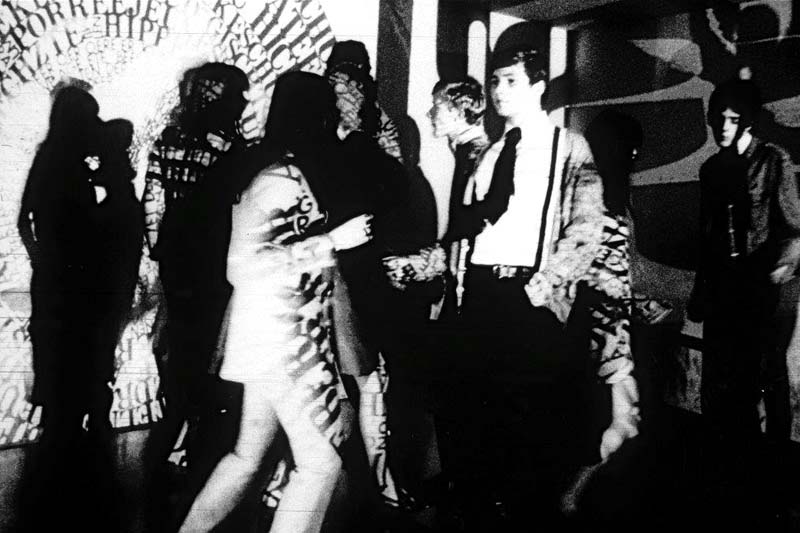

Intoxication and rebellion also went hand in hand at Creamcheese. The emerging drug culture found its way into the club through LSD and hashish, as well as the distorted sounds of a new music, with ‘See Emily Play’ by Pink Floyd and ‘Purple Haze’ by Jimi Hendrix. Although Creamcheese saw itself as an underground dance club, art was also an important factor in expressing the desired liberation.

In 1966, a few students from the art academy traveled to the USA and visited the club The Dom with Andy Warhol. Günther Uecker, who after experiencing the horrors of nights illuminated by bombing raids during the war now explored the beauty of light in his work through his light installations, was enthusiastic and brought the idea of a modern club in the style of the San Francisco psychedelic era to Düsseldorf.

The elaborate interior design, featuring the twenty-meter-long bar by Heinz Mack, a stage that doubled as a dance floor, the TV installation, and light show projectors, established Creamcheese as the first modern discotheque in Europe. The first flickering stroboscope on the mainland was built commercially in the club’s own workshop a short time later and was subsequently installed in many other discotheques.

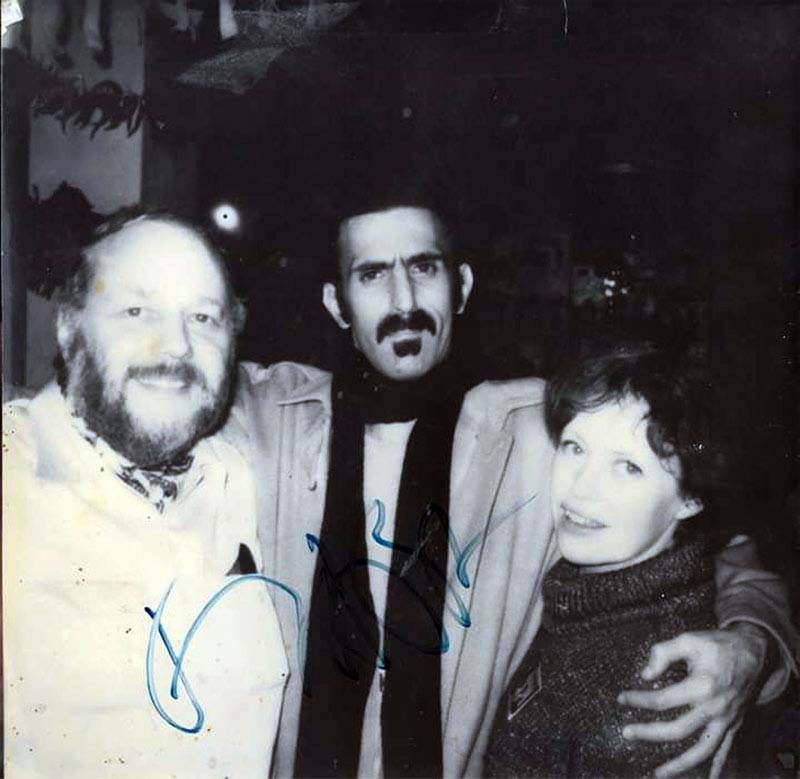

Frank Zappa was to become a friend of Creamcheese operators Bim and Achim Reinert in the years that followed and would visit the dance club frequently. Pop and protest were the hallmarks of Creamcheese, which saw itself as underground. Art should be on the street and the street in art. Everything was art. Everything was new. Above all, it was the music that played the leading role at Creamcheese, because the young people of the city wanted to party and celebrate a new life—a life that broke through boundaries and conventions in a drug-fueled frenzy, twitching and immersed in volleys of stroboscopic light. Creamcheese had it all. Drugs were consumed en masse and sold in the car park opposite. It should be noted that the club had to close at 1 a.m. due to the curfew, but reopened at 6 p.m. each day. As a ritual, ‘The Return of the Son of Monster Magnet’ played at 10 p.m., during which minors had to leave the club.

The rooms also provided space for performances, readings, and pub theatre. In 1968, Joseph Beuys staged his hand performance, accompanied by a soundtrack from ‘PissOff’ and Eberhard Kranemann. Kranemann would return to Creamcheese in 1970 for the first Kraftwerk concert and later run NEU! together with former Kraftwerk members Michael Rother and Klaus Dinger. Charlie Weiß, who also played with Kraftwerk in 1970, later teamed up with Helge Schneider, while the exceptional guitarist Houschäng Najadepour subsequently contributed his skills to Eliff and Guru Guru. In 1968, Creamcheese made the leap to the Documenta and was recreated there as a complete work of art. The club became world-famous within the music and art scene. Joshua White, the light show pioneer of the Fillmore East in New York, once stood in front of a closed door in 1969 because the venue was closed on Mondays, but he had the opportunity to illuminate a Creamcheese event at the Guggenheim Museum in 2014.

It is not surprising that Creamcheese became a role model for many clubs. As early as 1967, the organiser of the legendary Pop & Blues Festival opened the Pop-In in Essen after visiting Creamcheese. Conrad Schnitzler from Düsseldorf founded the Zodiak Free Arts Lab in West Berlin along similar lines. In the fashion city, music and fashion were closely linked, and the first boutiques featuring the latest British styles sprang up around Creamcheese. Mora, the club’s first barmaid who became a legend in the city centre during her lifetime, opened the Pop Off shop next to the club.

In 1976, the party was ended by the city of Düsseldorf, as the venue was considered an eyesore. At that time, the cultural achievements in music and art were disregarded, which makes it all the more surprising today that the city now seeks to promote these very successes. However, Creamcheese operator Achim Reinert quickly found a solution, and Creamcheese simply moved to a larger club under the new name Cream, located just a few minutes away in the historic city centre.

Unfortunately, the forced move meant that the new club was unable to replicate the success of the old one, although this was partly due to emerging trends such as punk rock. For a short time, the Ratinger Hof took over the leading role, even though it was run by an artist couple from the Creamcheese environment. This was where the revolution ate its own children, as proto-punk with bands like the Stooges and MC5 had also taken place at Creamcheese in the early 1970s.

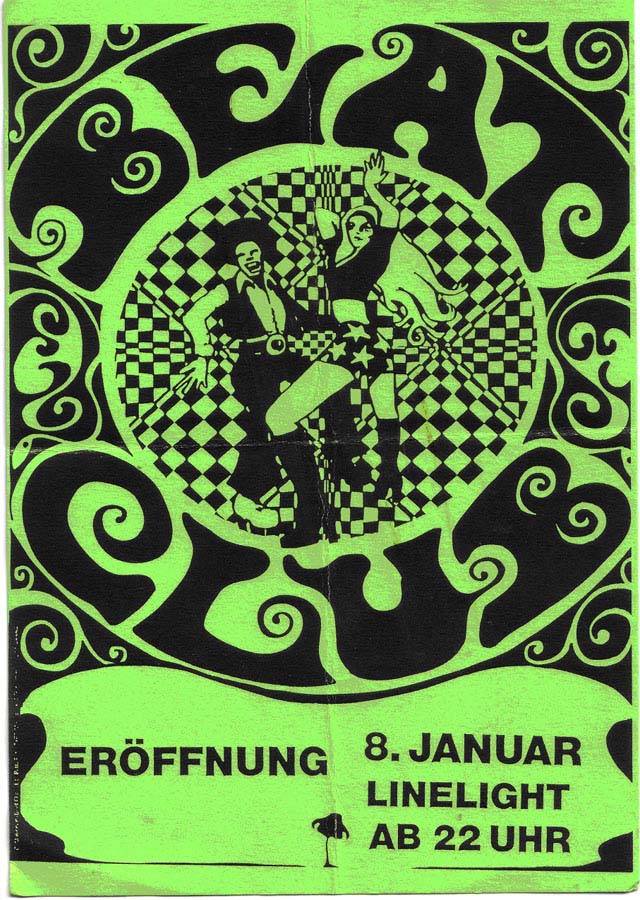

However, Cream also survived these trends and was to flourish again in the years that followed. For a few years, the club operated as Kick under new management before once again embracing the musical character of Düsseldorf as a centre of subculture under the name Line Light. The club’s interior is particularly noteworthy, as it retained key elements such as the seating stairs from Creamcheese and remained largely unchanged until its closure in 1992.

Line Light quickly established itself as a cross-scene meeting place and was one of the few clubs in the 1980s with a licence to stay open until the early hours of the morning. This contributed significantly to the gathering of night owls from all walks of life, who were able to inspire and stimulate one another. In the mid-1980s, the new sound of New Wave, which dominated the dance floor at Line Light, was played in almost every club in the city. International stars such as Christian Death from the emerging gothic rock scene were frequent guests. Iggy Pop, however, was denied access, as the manager at the time did not want “people from the rubbish bin” in his club. By the 1980s, many young guests were no longer aware of the historical significance of the venue, as hippie culture and krautrock had been discarded like hazardous waste.

It is all the more astonishing that at the beginning of 1992, a new party series under the name Beat Club revived the early days of Creamcheese, thus bringing the story full circle. To this day, Creamcheese and Line Light live on in the memories of their visitors, as every visit was a memorable event.

Even though the original venue closed in 1976, the spirit of Creamcheese lives on. Since 1977, Creamcheese, as a non-profit association, has carried on the tradition through events, keeping its cultural legacy alive. Today, it remains not only a chapter of the past but also an active part of the present.

Christian Koch

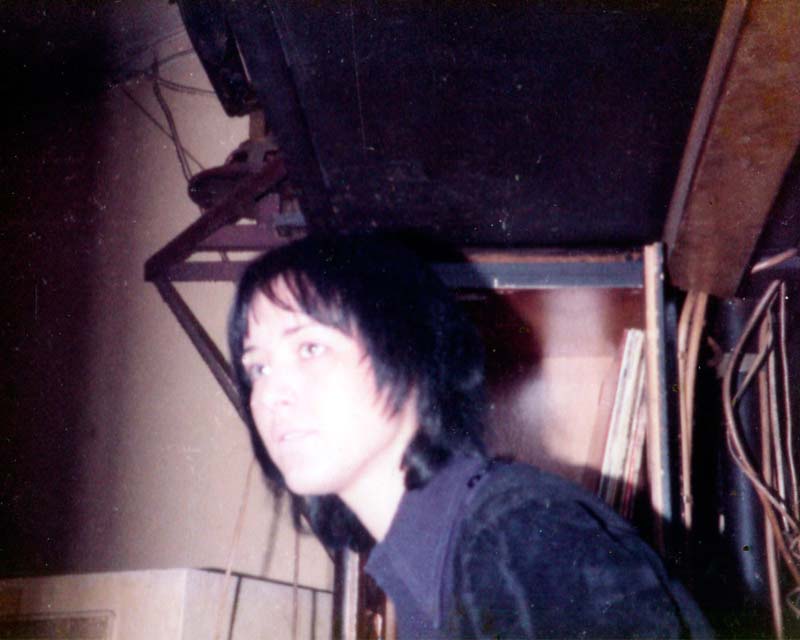

Headline photo: Creamchase owner Achim Reinert alongside the DJ, bringing the energy to life in the club. (Credit: Achim Reinert Collection)

Chteemcheese!

Very well written.

It was an irretrievably extraordinary time. I’m glad to have been a part of it.

Is it somehow documented when the “Kick”-era started and when Kick turns into Line Light?

Great article with fascinating details, thank you!

Sehr informativ, gut recherchiert und gut geschrieben!

@Nick Bauer: Kick started around October 1979 and LineLight opening was April 30st, 1982

Hut ab! Sehr gut recherchiert und geschrieben. Das Creamcheese war eine Institution, von der ich noch heute zehre!