Abronia Premiere ‘Weapons Against Progress’ and Dive Deep in a New Interview Ahead of ‘Shapes Unravel’

Abronia, the Portland based psych six-piece, continue to refine and expand their sound, and their forthcoming album ‘Shapes Unravel’ shows the band reaching a new creative peak.

Today, together with our full interview, we are premiering their new single ‘Weapons Against Progress,’ taken from the album, which arrives February 20th via Cardinal Fuzz and Feeding Tube Records. The track lands December 9th, accompanied by a shadow soaked video directed by pedal steel player Rick Pedrosa, and it captures the band in their most clear eyed form.

Abronia have long built their world around the hypnotic pulse of their 32 inch bass drum and the interplay of saxophone, pedal steel, and guitars that blur intensity with widescreen atmosphere. ‘Shapes Unravel’ stretches those elements further, expanding their palette without diluting the gravity of their core sound. ‘Weapons Against Progress’ channels the desolate, surreal landscape the band describes, a place scorched by greed, pollution, and generational abandonment. The song moves with a heavy inevitability, the vocals cutting through a dense churn of percussion and drone while the pedal steel wails like a warning siren. It is a meditation on trying to navigate a future shaped by the failures of those who came before.

Across ‘Shapes Unravel,’ Abronia push deeper into emotional and structural complexity. The album’s shifts between weight and stillness feel very intuitive, rooted in the group’s commitment to organic composition and their ability to inhabit a shared space with near telepathic sensitivity. As the record unfolds, grief becomes a gravitational force, but flashes of transcendence break through the darkness, illuminating new textures and new ways forward.

“We’re always kind of examining the dynamics in our music.”

Shaver moving from the big drum to guitar, and Grubaugh stepping onto percussion, is a huge internal shift. How did that change the band’s concept, considering that 32-inch drum is such a signature presence? Was the decision to expand the instrumentation (strings/brass) a direct compensation for or a reaction to that shift in the core rhythmic identity?

Well, Robert Grubaugh played the drum for us a few years back when we toured Europe–he filled in for Shaver on that tour, so we were already used to playing with Robert when he officially joined the band. I wouldn’t say any of the lineup changes that we’ve had have fundamentally changed the band’s core concept. The core concept has stayed pretty much intact since our first show. And it’s the same big drum and the same cymbal—the same shakers and tambourines and the same mallets. Those things are collective band property. The concept is still intact!

As far as expanding the instrumentation, I don’t think that idea had anything to do with the change in membership. For one thing, we only did it on two of the songs on the album, and one of those only has the extra stuff for the last minute of the song.

I think the expanded instrumentation just came about from people at practice saying, “Oh I could hear trumpets on this”–“I want strings on this.” So we decided to try it. It wasn’t a conscious move to change the overall concept–just adding some ornaments.

The album moves through “grief” and “transcendence.” Can you walk us through how you use the internal dynamics of your six-piece setup..the intensity of the tenor sax against the sprawl of the pedal steel, for example…

We’re always kind of examining the dynamics in our music. It’s hard to really explain in detail because it’s just something that happens organically in the practice space. We’ve been doing this long enough that we’re familiar with the timbres and the sonic space each person inhabits, so it’s cool to kind of experiment with a specific instrument highlighting a melody or a certain instrument doing a harmony with another. The rhythms are just as crucial as the melodic elements, so sometimes it’s figuring out how everything interacts and which timbres get the spotlight at any given time.

Your pedal steel work is often far from its roots, carving out these eerie, atmospheric textures that fit right into the “Eastern drone” and “avant-jazz” pockets. When you’re writing, what are the primary effects or microtonal techniques you lean on to strip the instrument of its familiar C&W associations and integrate it seamlessly into the psych noise floor?

Rick Pedrosa (Abronia Pedal Steel Player): Reverb, some delay, some distortion. Dissonant chords, approaching the instrument thinking more like a horn, keyboard or voice. Definitely vocal forward.

Eric Crespo: I’ll add that the pedal steel isn’t a slave to frets like the rest of the guitars in the band.

‘New Imposition’ is a heavy, specific document of urban decay and addiction. How does the sheer viciousness and visceral detail of that lived-in scene inform the tracks that follow, especially those without overt lyrics? Is the music serving as a psychological landscape that contains or attempts to move past the trauma described in that first single?

Oh, l don’t know if there’s anything specific in the first track that informs the tracks that come after it. Maybe there is! Listen to the album and decide for yourselves!

Playing music is something that I think I can safely say that everyone in Abronia uses as a psychological tool to deal and heal.

Is there anyone who plays music who doesn’t use it for that purpose? I mean everyone probably has multiple reasons for playing music, but I’d be very surprised to find out if someone who played music felt like there was no psychological component to it whatsoever.

We’re out here just trying to tap into the mystery and transcend the bullshit of being alive. Music is magic.

Your sound feels like part ritual, part widescreen cinematic composition. When you’re in the room together at Echo Echo, how much of that final recorded take is a meticulously arranged score, and how much is truly spontaneous, unhinged improvisation captured in the moment? Where does the band draw the line between jamming and composing?

We’re not one of those bands who spends a long time working out ideas in the recording studio or doing endless takes. By the time we get to the studio, we know pretty well what we’re going to be recording. The bulk of our hours spent together are in the practice space.

When we’re coming up with ideas in the practice space, we make sure we get new ideas recorded onto a phone or whatever, and then those recordings get sent to everyone in the band before the next practice. We use those recordings as a reference and then we refine and refine some more–removing things, adding other things–tweaking until everything feels right (whatever “right” is). As far as spontaneous improvisation, we leave sections where things are intentionally left loose and open–sections within the compositions that are going to be a little different every time we play them.

Running a six-piece without a traditional drum kit, relying instead on the “big drum” and specialized percussion, creates this massive, slow-moving force. What are the rhythmic challenges and advantages of this setup, particularly in maintaining groove and tempo over long, droney passages?

Part of the impetus to just have one drum in the band was to deliberately set up a limitation that keeps us bent toward minimalism. In my previous bands, I got a little tired of asking drummers to play less all the time. I figured if you give them one drum and a cymbal that’d be half the battle right there.

Something I didn’t really consider early on, but that I’ve found to be true, is that it makes us really aware of what the drum is doing at all times. I feel like when I’ve been in bands with a traditional drum set, it’s somehow easier to sort of tune out what the drummer is doing. Probably because one is so used to hearing a drum set in the context of a rock band that it’s less considered. With just the one drum, there’s kind of a forced minimalism, so it makes the hits that do happen have more importance or something.

It’s kind of a fun challenge to come up with solutions if we’re wanting some kind of percussion/drum feel that the drum won’t easily allow for. There’s two hands so there’s usually two different things that go in each hand–a big orchestral bass drum mallet in one hand and a tambourine, shaker, or stick in the other is common, and there’s the rim of the drum so that gets used. We often try to solve these drum puzzles by getting someone else to play additional percussion. Or some other instrument will have to fill the role that you might normally get from someone playing a drum set. Maybe someone has to mimic a snare roll on a guitar or something. The drum always has the low end covered, so that’s rarely a problem, unless we’re looking for different levels of low end, like you’d get from a floor tom and a kick drum.

But if Rick or Keelin can add a shaker or a tambourine, it can make this sort of four armed drummer sort of thing that gives us a sound that you wouldn’t get from having a drum set in the band. We have a song where on the end section, Keelin plays the drum with sticks while Robert is playing with the big mallet and a tambourine, so they’re both wailing on it at the same time. That’s fun. Maybe we should try that again sometime.

Working with Larry Crane again means you are chasing a specific fidelity. For an album introducing orchestrated layers, how did you balance capturing the air and detail of the strings and brass with the absolute necessity of retaining the in the room punch of the guitars, the big drum, and Keelin’s vocals? What was the biggest challenge in keeping the mix from feeling diluted?

The way we’ve mixed with Larry is we send him the tracks, along with our rough mixes and notes, and he does two days of mixing on his own through his console and the analog outboard gear at Jackpot! (his studio), and at the end of his second day of work, he sends his mixes to us. We all listen to the mixes the night he sends them to us and we all write our own notes of things we want to change. Then we all meet up at his studio on the third day and we sit around and make the tweaks, and debate in real time about what needs to come up or down or what needs less reverb or whatever. Then we leave the studio and that’s the mix.

We know pretty well what the songs need by the time we get to Jackpot. I’m a recording/mix engineer so we demo out the songs in a studio before we go to the studio for the “real” sessions.

From those initial demos, we might make little tweaks to the compositions and then we go back and record for real using what we learned from the demoing process.

We did the mixing differently for our first two albums and that was sort of a miserable process of entertaining six different opinions through email and text message–the mixing can go on forever in that scenario. It’s nice to approach mixing in a way where there’s a specific day where we can leave the studio and it feels final. And working with someone like Larry, for one, he’s a neutral party–someone outside of the band to bounce ideas and opinions off of. Sometimes we’re a little too close to it to see it clearly. And another thing–he’s made so many albums, if there’s something that gets past him and all six of us, well then it can’t be that egregious, and I know I probably shouldn’t worry about it, because I, for one, am sure prone to sweating insignificant details in recordings.

Mixing the strings and brass in there wasn’t really that big of a deal. Once you have all the other instruments in place, you kind of just put ‘em in there.

Keelin introduces the flute for just one track. In a band that deals in such commanding, heavy textures, the flute is a startling, almost fragile contrast. What specific narrative or timbral role did you assign to that instrument on “Gemini,” and why was it the only moment it was allowed to puncture the dense atmosphere?

I don’t really remember how that even happened. She may have just said, “Maybe I should play flute on this one,” or something like that. I do think she’s been threatening to break out the flute for a few years. She finally did it. Now that the flute’s outta the bag, we might see more of it.

The music is incredibly dense and complex, but the idea that “hooks aplenty” lurk beneath the surface suggests a deliberate structural decision. In the context of Abronia, what constitutes a hook? Is it a cyclical guitar riff, a repeated sax phrase, or is it simply a rhythmic pattern that keeps the listener grounded in the weather system of the song?

I think of a hook as something that sticks in your head and makes you remember a piece of music after it’s over–something you can hum to yourself. I don’t really sit down and try to do it, but there’s some part of me that seems inclined to come up with catchy little melodies and things. And other folks in the band tend to come up with those little hooks too. It’s never really discussed though. We’ve never talked about trying to make something catchy or anything like that.

What are the specific aspects of the Abronia sound that you are now finding restrictive, and what conceptual corner of your universe are you already eyeing for the next stylistic deconstruction?

Things evolve pretty organically in this band. I don’t think anyone has any grand plan about what our next moves are going to be. We’ll keep exploring new stuff in the practice space and doing what we do.

It naturally gets a little harder when you’re four albums in and you’ve kind of already plucked the low-hanging fruit and you’re trying to find new territory while still making something that feels like your band. But I don’t feel like we’re anywhere close to the end of the rope.

I feel like we’re really having fun with making the arrangements more ornate and rich. More thoughtful composition and finding new ways for excitement and depth. It’s cool to have six people playing the music–it allows for cool orchestral maneuvers (in the dark?) to transpire. Making music with Abronia is satisfying as hell.

There’s a lot of directions this band can go at any given time and even within a song, so it doesn’t feel too restrictive in general. From my personal perspective, I’ve lately kind of felt like I’m having more fun than ever coming up with guitar parts.

I’ll sit down to play and come up with just the very start of a little riff and it sort of feels like a little creature or a little trickster spirit or something showed itself to me and then I have to follow it down the path and try to find where it went. It’ll yell out, “I’m right over here,” but the way to get “there” is sort of a mysterious path and sometimes I’ll get lost. I’ll never find it if I take the obvious route, but sometimes I have to try the obvious route, just to know what that path looks like. But generally, I have to do things that surprise me in order to find what I’m looking for. It keeps me coming back to the guitar (even when I should be doing something else). It’s an engaging adventure to be sure.

Klemen Breznikar

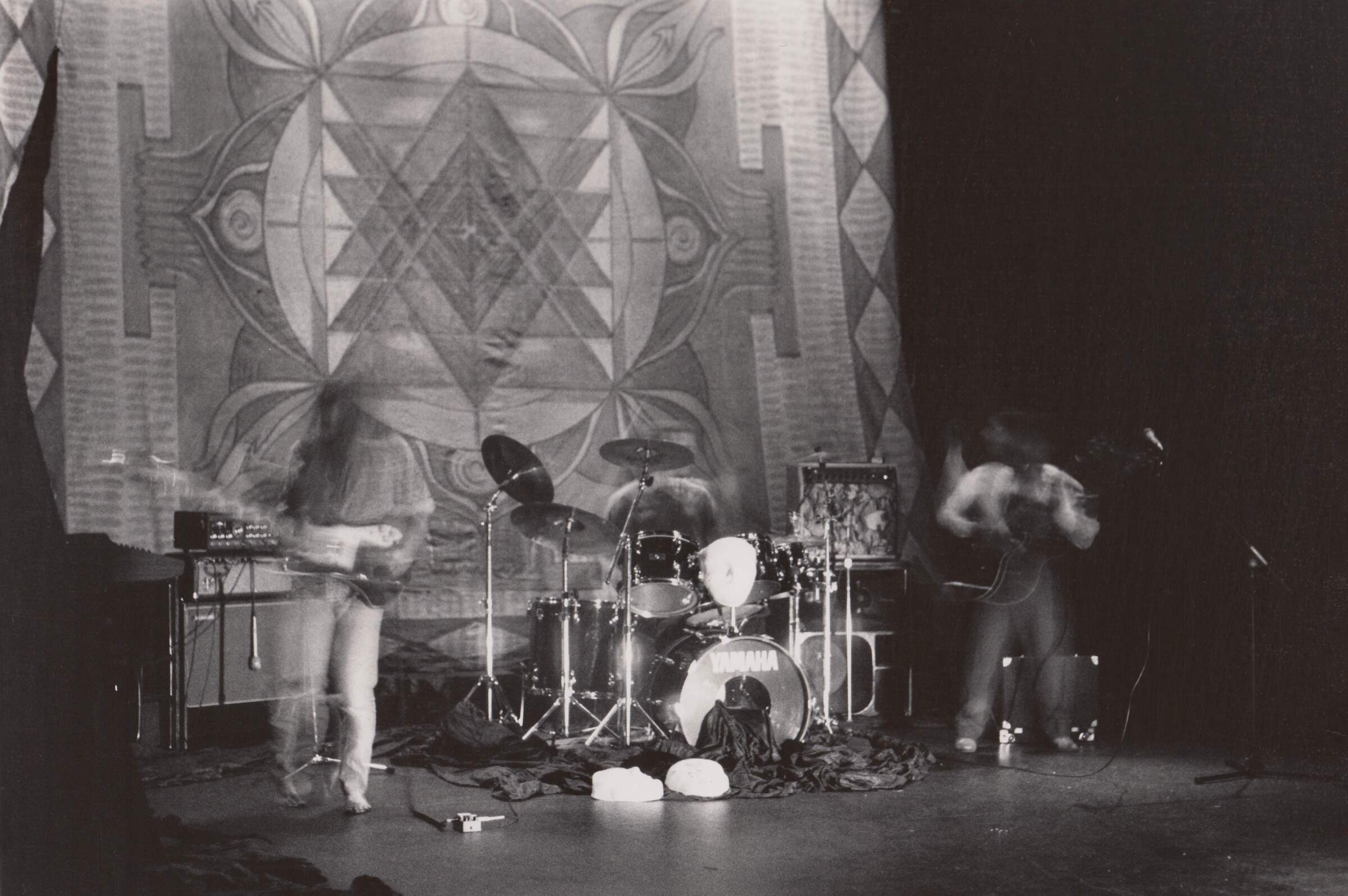

Headline photo: Abronia

Abronia Facebook / Instagram / X / Bandcamp

Cardinal Fuzz Records Facebook / X / Bigcartel / Bandcamp

Feeding Tube Records Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / X / Bandcamp