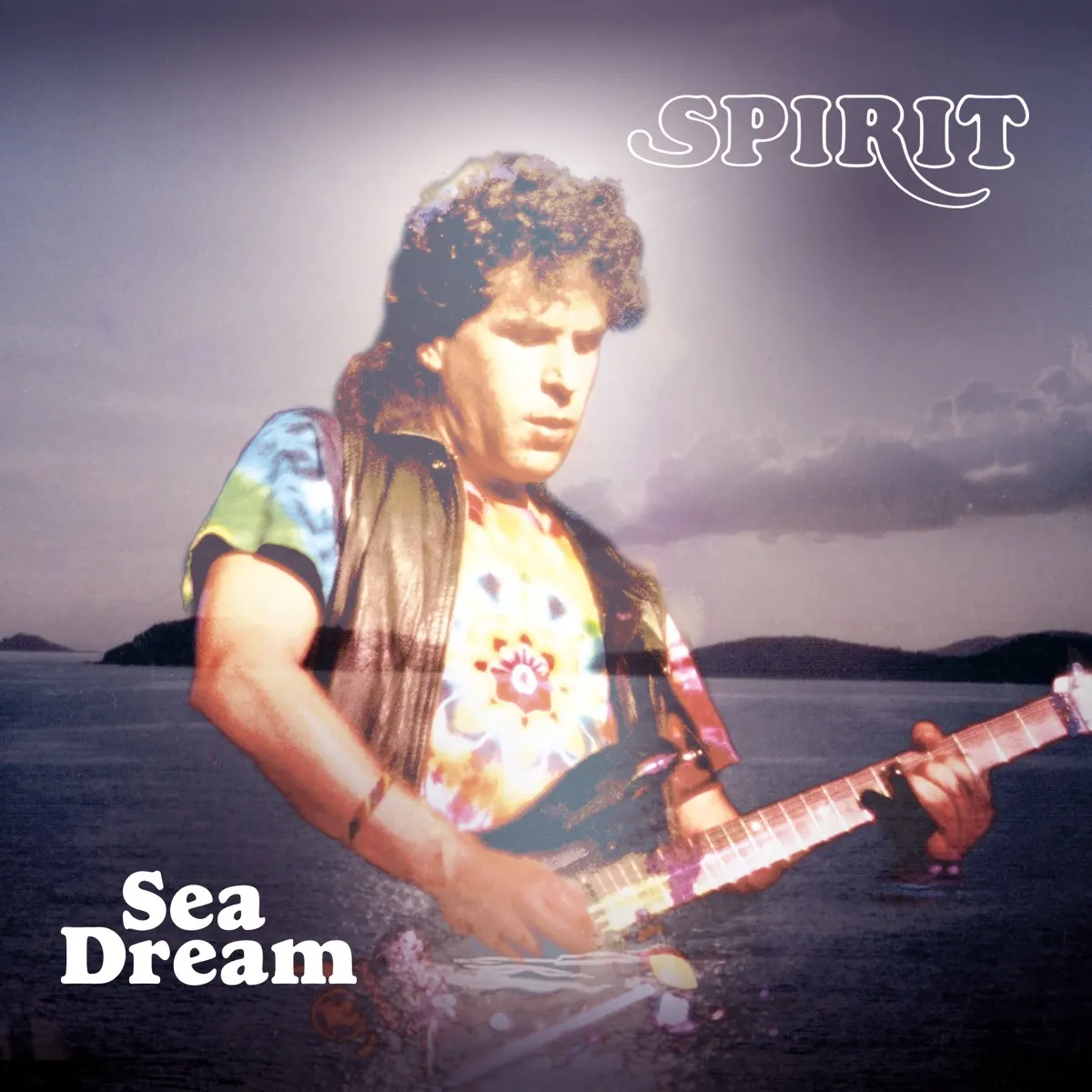

‘Journey to the Ancient’: Inside Yusuf Mumin’s Long-Lost Recordings and Rare Interview

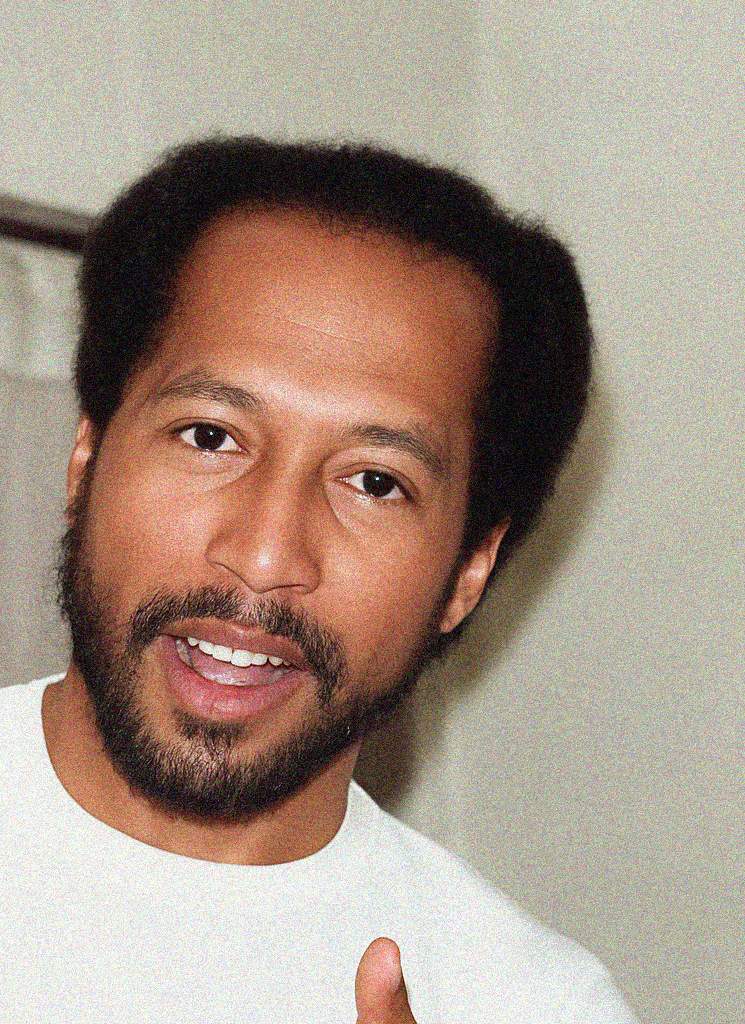

Yusuf Mumin, alto saxophonist and co-founder of the Black Unity Trio, remains one of the most elusive figures within the Great Black Music continuum.

With ‘Journey to the Ancient,’ Wewantsounds presents the first release to bear his name, drawn from a personal archive he has tended for decades. These recordings, undated but unmistakably rooted in the spiritual imagination of the late 1960s and beyond, reveal a music that Mumin describes as “transcendental communication, not reliant on standard arrangement.”

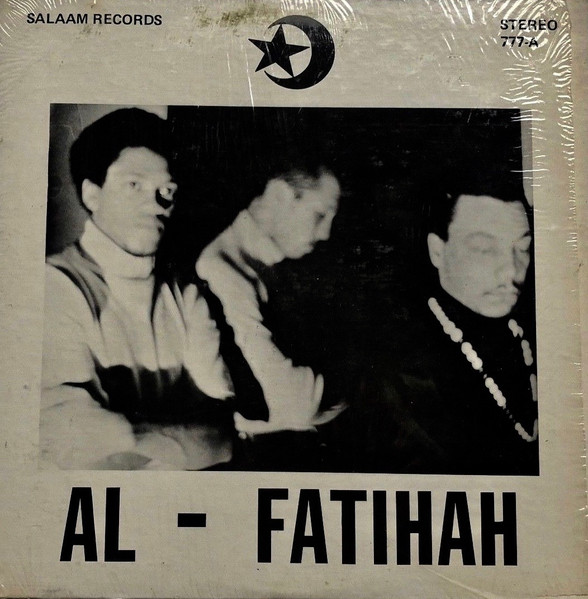

Mumin emerged in Cleveland’s fertile avant-garde alongside Abdul Wadud and Hasan Shahid, forging ‘Al-Fatihah,’ a 1968 record whose raw metaphysical current became a cornerstone of Midwestern free jazz. Themes of cyclical time, diasporic memory, and spiritual striving course through these newly uncovered pieces, echoing his conviction that “continuity… defies simple chronology.”

Remastered by Colorsound Studio and accompanied by newly commissioned liner notes,’ Journey to the Ancient’ extends the arc of a musician whose work has long existed in the private realm of tapes, memory, and oral history. Its release not only restores music but illuminates a vital and still under-recognised voice within the broader history of experimental Black music.

“The music I play comes under the heading of transcendental communication”

‘Journey to the Ancient’ is being presented as previously unreleased music from your personal archive. Can you illuminate the nature of this archive? Was it a cataloged collection or a more spontaneous body of work?

Yusuf Mumin: This music and these tapes were preserved by my own effort. After misplacing material and having so much damaged, I found it mentally disturbing, not because of any lost monetary value, but because of the energy and sentiment put into the music. As time drifted by, I found the stored away music to be an ongoing process for understanding myself. Even today I’m working on music that I started long ago.

I guess you could say it’s like a person writing a book that is not completed in one setting. The writer may even have a writer’s block, then there comes a moment of contemplation and the self portrait takes on a life of its own, and the art becomes part of self development, an ongoing project. However, in that project a self portrait is developed and it becomes a matter of what you see and what building blocks should be used.

Tapes were transferred to a digital format. The point I’m trying to make here is this. The American songbook.

Look at how the jazz musicians of the forties and fifties treated that music. They improvised or layered over the initial structure and creatively made different arrangements. So, that being said, sometimes over the years I would have a musical idea and record it before it got away. I would archive the idea and revisit it at some other time, and this became a hobby.

The music I play comes under the heading of transcendental communication, not reliant on standard arrangement. However, maintaining continuity between the intro and the outro does occur, which involves creative interplay between the instrumentations. So this should answer your following question.

The recordings are undated. In the spirit of the music’s timelessness, how much do you believe the specific context of their creation matters? Do these pieces exist in a continuum, or do you recall distinct periods of creative exploration that might have given rise to them?

There is an ongoing philosophical connection to the music that tells a story, and it is closely related to the title and the sounds recorded in 1968 on ‘Al-Fatihah,’ ‘Birth, Life, And Death’…

First let me point out that the title ‘Journey to the Ancient’ has been purposely worded in such a way, rather than saying “Journey Back to the Ancient.” In some ancient cultures, time itself was cyclical and cosmic ages repeat, like in music where endless music is expressed using only a handful of notes.

To explain this in terms of heliocentric time. World events are measured by the circumference of the earth, the moon cycles, and the female clock of destiny. The journey to the ancient is a return to the beginning, like the phases of the moon and the constant rotation of the planets which serve as predictions.

Ecclesiastes 1:9:

“What has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done; there is nothing new under the sun.”

Inevitability. What is woven throughout the composition, and at the end of each cycle, the content of the hourglass is flipped and the essence is released in reverse order.

We come into this world and history repeats itself until the individual is fulfilled through obtaining necessary degrees of life and is no longer controlled by the recurring gravity of rebirth.

So there is a continuum, and I think the free form music accumulates and expands as time goes by. To relegate it to a moment in the sixties truly lacks understanding. I consider relegating the music in such a way to be a form of aborting the music in its womb before reaching full term.

I would go so far as to say the music has a multi-directional future with a very broad parameter capable of communicating with worlds. NASA sent the Voyager Golden Record in hopes of communicating with extra-terrestrials.

We know that at least two sessions are represented on the album. What do you remember about the confluence of musical minds in these sessions? How did the dynamic with drummer William Holmes, an associate of the late Sonny Simmons, manifest? What was the shared musical language and what was left unspoken?

I don’t know the extent of William Holmes’s relationship with Sonny Simmons. He also was in communication with Pharaoh Sanders. Many raindrops fall into the river and they all become one flow of water in their journey toward the sea. Creating with Brother Holmes was a real pleasure and creative experience. I have other sessions with him. I have to search through my storage.

“I like to think of music as a conversation, a language.”

The album is described as a powerful blend of serene spiritual jazz and fiery sonic intensity. How do you reconcile these two seemingly disparate poles in your music? Is this a deliberate duality, a reflection of the human experience, or a natural manifestation of the creative flow you were tapping into?

I like to think of music as a conversation, a language.

Human beings all over the world understand laughter and sorrow. Sometimes there is quiet before and after a storm. The same destructive forces of nature also bring forth the delicate flower. When it comes to music I do think in terms of metaphysical temperance. However, extremes do exist. It is called the four seasons. The birds fly south while humans pull out the shovels.

Your work has been deeply influenced by spiritual and esoteric traditions. How did these beliefs translate into your approach to improvisation and composition? It’s also noted that your original inspiration was Yusef Lateef.

I think self expression is very important in any individual’s life. Esoteric rituals and religious thought that require secrecy carry with them a degree of selfishness and are found to be tools for dictators and manipulation, which I am personally against. I have met and known people in all walks of life. However, each individual is a unique creation, so there is no real need to try to be like someone else.

Yusef Lateef was like a big brother to me when I finally had the opportunity to meet him in Los Angeles. I had already recorded with the Black Unity Trio. I gave him a copy of the album and we talked about the music being presented. He disclosed that some of his music the people wouldn’t understand.

To digress for a moment, there were all types of philosophies descending on America and the music was right there in the mix. Going back to around 1963, I found it necessary to gain some equilibrium. There was a lot of turmoil and confusion brewing in the sixties. In fact it was so much going on that I had to take time out and meditate on the big picture itself. Brother Lateef’s music filled a lot of those empty moments.

As it turned out, when we did meet we knew some of the same people in Cleveland and Pakistani people involved with the early beginnings of the Almadi in Detroit. As it turned out, musically neither of us were sold on the term jazz.

Autophysiopsychic is a term coined by Brother Lateef, meaning music from one’s physical, mental, and spiritual self. It describes music that is not merely for entertainment but serves as a conduit for the artist’s entire being and a deeper connection to creation. Lateef developed this concept to replace the term jazz, which he felt was a commercialized and inadequate label for the music’s rich artistic and spiritual depth.

Brother Lateef back in the fifties opened my mind to the far reaching possibilities of music beyond the commercial. The time we spent together he talked about his early start in music which took place in Detroit along with Milt Jackson of the Modern Jazz Quartet.

We broke bread together and spent time moving around Los Angeles. Lateef I found to be very polite. I think that stuck with me as much as his music. He was keenly sensitive and spiritually in tune.

‘Bakumbadei’: This is a very short, poignant piece, a tribute to Abdul Wadud. Can you tell us about the decision to open the album with this track? What does the cello and voice combination represent in this context?

The whisper between worlds, when memory becomes song and truth reawakens with rhythm.

It is the utterance of reunion, the breath where the departed and the living walk together in melody.

To say ‘Bakumbadei’ is to invoke the sound of remembrance, the echo of spirit crossing the threshold of time. The cello is in remembrance with pronounced double stops, a form mastered by Abdul Wadud. This musical idea also serves as a libation.

‘Distant Land’: Given the tracklist, this piece follows the journey to the ancient. What is this distant land? Is it a destination found, or a new horizon to be explored?

A distant land is a place where exiles wear crowns and gravity weeps. People suffer in this world, often at the hands of injustice.

The earth takes their flesh body. In this view gravity has a relationship with the carnal body, the flesh body. However, the soul escapes, for it is that aspect of self that is tethered to the unseen world while we live. After this life there is a soaring free of gravity.

A distant land. Gravity weeps because it no longer has power over the soul. A distant land is a contemplation and a toiling between worlds, a sound of hand arts and crafts.

‘Diaspora Impressionism’: This is the longest track on the album, an eighteen minute exploration. What does ‘Diaspora Impressionism’ mean to you? How did you, through the medium of the alto saxophone, seek to capture the fragmented yet deeply connected experience of the diaspora?

Diaspora is generally thought of as displacement of people across the ocean. Here the attempt is to paint an impression of people being evicted from their homes and scattered about the cities with little to no means. Little children who can’t pull the pieces of their lives together, families falling out of love, and emotions rising like trees without roots and rivers that cannot find the sea.

Your work as Joseph W Phillips and later as Yusuf Mumin has been a continuous spiritual and artistic evolution. How do you view the relationship between the music of the Black Unity Trio’s ‘Al-Fatihah’ and the material on ‘Journey to the Ancient’?

Joseph Phillips had many meaningful things take place in his life. Of course at the time there were blind spots. However, the musical journey has not been interrupted. Some ideas from way back in the fifties have taken a wider elliptical orbit, but still they come around, bridging ideas through the transition of name change and time.

Do you see a clear line of progression, a divergence, or a deeper continuity that defies simple chronology?

Continuity that defies simple chronology.

If you look at the story lines of the titles with the Black Unity Trio next to ‘Journey to the Ancient,’ there is continuity in the approach because this music is moving in a circle, not based upon a standard formula that is staged in the realm of do and do not, not metaphysics or the higher sixth sense. In essence, music goes beyond exciting the five senses and spectacle.

Here, vibration becomes revelation. Tone becomes truth. Silence becomes the breath of origin.

If you do not mind, would you be willing to take some time and recall the recording and making of the 1969 album ‘Al-Fatihah’?

Actually we recorded and made the album in 1968 when the social and political climate was very high. The cool beatnik had become a hippie and Timothy Leary was preaching turn on, tune in, and drop out. The flower children were running away from home and smoking pot. Then there were the sixties assassinations and the Vietnam War.

Cleveland had a black mayor by the name of Carl Stokes, who grew up in the same housing project that Abdul Wadud and I grew up in. Abdul Wadud was getting ready to leave the Oberlin Conservatory of Music to play with the New Jersey Symphony, and I had my sights on California. Hasan had unfinished business in Alabama. However, before any of that took place, we gave a concert at Case Western Reserve University, took the proceeds, and pressed five hundred copies of ‘Al-Fatihah’.

For you, what does it mean to have your work finally presented to the world in this new context? Does it change your perception of the music now that it is being shared after remaining unheard for so long?

When a tree is planted, the seed is buried in the dark soil. So when that tree begins to grow it blossoms outward and upward, while its roots are still buried in the dirt. My hope is for the music to find a pathway and be meaningful. Even the smallest pebble when cast into the sea makes a wave and becomes part of the face of the deep. In a word, yes. I am happy for the art form.

Cleveland was home to pioneering figures like Albert Ayler, Norman Howard, and yourself. Can you describe the artistic kinship and creative dialogue among the musicians in that scene?

Cleveland was a major hub for many creative people coming to entertain, both musicians, poets, and actors. Cleveland was in touch.

The underground is often associated with these movements. What was it like for a musician in Cleveland’s free jazz scene to create such challenging, non commercial music during that period? Was there a sense of playing for a dedicated, in the know audience, or were you navigating a broader and perhaps less receptive public?

The local musicians thought we were losing our minds, if not crazy, because we could not play in clubs where the only reason for being there was to sell liquor. A sad thing that I saw was that a lot of those club jumpers wanted to be so much like Charlie Parker, so what did they do? They started shooting smack and got real slick.

The Black Unity Trio was playing cultural centers and colleges. What we were doing was based on art, but some people just couldn’t dig it. It was the revolutionary minded people who supported us.

What currently occupies your life?

I’m in the same orbit set a long time ago. My fruit trees are important, growing food, maintaining a house, and generally staying on top of things. I have inherited the vibraharp my brother owned that I started on in 1961. It is presenting a degree of tranquility, along with my daughter’s poetry and mystery stories she is writing, which has led me to keyboard arrangement and science fiction and theater sounds.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Yusuf Mumin (Credit: private archive)

Wewantsounds Website / Facebook / Instagram / X / YouTube / Bandcamp