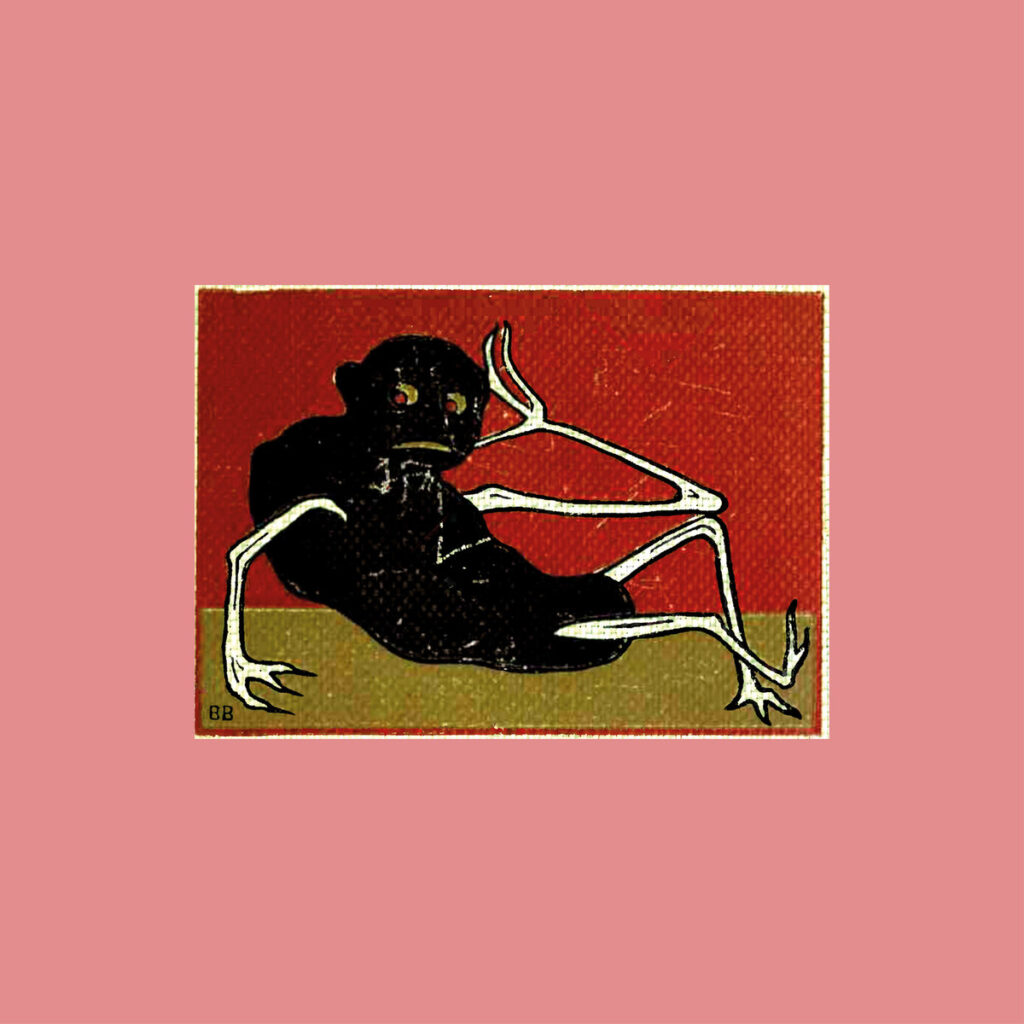

Gurry Wurry | Interview | New Album, ‘Happy For Now’

‘Happy For Now’ is the highly anticipated follow-up album from Gurry Wurry, the solo project of Scottish indie-psych-pop artist Dave King.

‘Happy For Now’ was recorded with indie legend Rod Jones, known for his work with Idlewild, Hamish Hawk, and Redolent. This album is a heartfelt ode to the art of caring less—or at least trying to do so. It explores the beauty found in the fragility of existence, acknowledging the delicate balance between contentment and the inevitable sadness that lingers.

With themes ranging from car crashes to fly-tipping and the complexities of aging and infidelity, ‘Happy For Now’ teeters on the brink of chaos. Its dissonant harmonies, wonky rhythms, and King’s delicate voice create a tapestry of sound that feels both introspective and lively. In this half-dreamt world, where a California breeze blows through the streets of Leith, listeners find a laid-back vibe reminiscent of Randy Newman vibing with The Beta Band, while Steely Dan goes lo-fi. It’s as if Kraftwerk shares a writers’ room with John Martyn and Thelonious Monk, reflecting the eclectic taste of an artist who has been collecting records for 25 years.

Ultimately, ‘Happy For Now’ offers a warm, woozy, anaesthetic pop sound that serves as alternative medicine for troubled times. The album is available in a limited edition cassette, as a digital download, and across all streaming platforms.

“It’s about the happiness that waits on the edge of sadness”

‘Happy For Now’ feels like a paradox—an upbeat album that can’t quite shake off the sadness. Can you take us through the emotional journey that shaped this album?

Dave King: Yeah, you’re exactly right. I’d had a few rubbish years and stored up quite a lot of feelings that fueled the first album. But then something changed. I felt a lot lighter and happier to be making music again. I felt more comfortable than I’d ever been, and I really wanted to make an upbeat album. As I started writing it, I just kept getting drawn back into melancholic tunes, and the whole thing became a bit of a battle between happy and sad until I realized that was kind of the whole point. It’s about the happiness that waits on the edge of sadness, or the sadness that waits on the edge of happiness. The impermanence of this whole thing.

Your music draws on a vast array of influences, from Randy Newman to The Beta Band, and even Steely Dan. How do you navigate such eclectic influences to create something distinctly “Gurry Wurry”?

I’ve always found it quite easy to make something my own just by following my own tastes. I listen to a huge, huge range of music, but there’s always a particular thing about each artist that I love. And I’ll take inspiration from that one thing rather than trying to make songs that actually sound like the artists. I get fascinated by music in quite a broken-down, modular way. So with Randy Newman, it’s the direct, simple fragility of the lyrics and vocal. With The Beta Band, it’s the lazy bounce of the grooves. With Steely Dan, it’s that sense of mischief and invention. It’s the dissonance of Thelonious Monk. The hooks of Hall and Oates. The angularity of Joy Division.

Of course, I never successfully recreate any of these guys because they’re all geniuses. And I don’t have the patience to faithfully recreate someone else’s music. I get bored when things feel familiar. There’s no point in sounding like them when you can just put their records on. I’m always chasing a new sound. But all those little elements and lessons go into everything I make, and I just keep playing until I come up with something that catches my ear.

The themes in ‘Happy For Now’ range from car crashes to aging and infidelity. How do you approach songwriting on such diverse topics while maintaining a cohesive sound and narrative throughout the album?

For me, it’s all about how those topics and themes make you feel. I find if you focus on the feeling, then even the most disparate scenarios can feel coherent together. Because it’s all being filtered through the same body and brain. It’s a bit like a soup – it doesn’t really matter what vegetables you put in there. Some are gonna be sharper than others, but in the end, it all tastes like soup. I also really love the surprise you get when things shouldn’t work together but do.

Can you share some further words about the recording and production process?

Absolutely. So I recorded all the music in my living room in Leith over a period of about 7 or 8 months. I’d just sit on my own into the wee small hours of the night, working away on songs. Sometimes they’d start with a riff, sometimes with a chord progression, sometimes a melody. Generally, I recorded the keys first.

Once I had the rough groove going, I’d record a drum track on my sampler—I played them in on the pads to get a real groove rather than using a quantized drum machine pattern. I’d then re-record the keys to lock in with the drums. Then I’d get the bass down, which was typically all synth bass. I got quite addicted to a real squelchy, phat bass sound on this one. And from then on, it was a bit of a free-for-all. I’d just pick up instruments and do 5 or 10 live takes on each to see what I might come up with.

I’d listen back and chop up the bits I actually liked. Then listen again and again, and keep deleting until I heard only the best bits. When I was happy, I’d go back in and record a proper take of each. Although I often found the first improvised take had a better feeling, so on quite a few songs I ended up using the demo rather than the cleaned-up version. Like the little tinkly piano part on ‘Sin Doesn’t Smoke Now’—that’s just one improvised take that I will never be able to play again. There was no thought; it was like someone else was controlling my hands for that one.

When I had the songs together, I used a decent amount of tape saturation and sort of vibey, tremolo-style effects to glue everything together and give it a bit more warmth. And then it was over to Rod in the studio.

Your collaboration with Rod Jones is a significant aspect of this album. How did working with Rod influence the final sound of ‘Happy For Now’? Were there any moments in the studio where his input completely changed the direction of a track?

Yeah, Rod was brilliant to work with, and he had a big influence on the final sound of the album.

In terms of the music, it all stayed pretty true to my original homemade tracks. What Rod brought was real clarity. He made so much room in the mix. I still have no idea how he did it, but you could suddenly hear all the distinct parts. We’ve got quite different brains like that—he’s got an insanely well-tuned ear and a real appetite for tidiness and clarity. He’s a super precise guy, whereas I’m a messy listener and a messy player. I hear things all wrong, and I actively enjoy the muddiness, the dissonance, the wonky. I’m most comfortable in a mess (my living room can attest to that).

But vocally, Rod changed everything. I’d gone into the studio assuming we’d double-track my vocals and keep them quite low in the mix. I wasn’t as confident in my voice as I was in my music. But he was having none of it. He said the strength of my voice was in its frailty, and that frailty needed to be the hero of the song—to be recorded up close and to be right at the front of the mix. Exposed. I was pretty nervous about it, to be honest, and it made the tracks feel really different from what I expected. But I came to love the way it sounds, and in the end, I found a bit of confidence in my weird voice. I’ll always be grateful to him for that.

He also has a ridiculously good ear for harmony, and he really helped me tighten those up—that was the toughest day in the studio!

“Dissonance has always drawn me in”

The production on the album embraces dissonant harmonies and wonky rhythms, which give it a very distinct feel. How much of this was premeditated, and how much evolved organically during the recording process?

I record alone at home, so I have a lot of freedom—in terms of time, money, and confidence—to just play anything and see what happens. So I think I was more open to taking risks than I might’ve been in a studio with a band and a deadline.

Dissonance has always drawn me in, and it often happened pretty naturally on these songs. But there were times where I made it happen. I don’t like songs to be too ‘on the nose.’ So if I felt something was a bit obvious or getting a bit sentimental, then I’d try and break it up with a really gnarly note. About halfway through the album, I realized that was going to be a bit of the signature sound for it. That if the album concept was a contrast of happy/sad, then the album sound should also be a contrast of harmony and dissonance.

You’ve chosen to release ‘Happy For Now’ on limited edition cassette. What motivated that choice in the digital age? Do you feel there’s something inherently nostalgic or meaningful about physical media, especially cassettes?

I grew up with cassette tapes, CDs, and my dad’s records. I own physical copies of all my favorite albums. I dunno, it’s hard to explain, and it makes me feel 100 years old, but to me, an album just isn’t real until I can hold it in my hand. I get a real buzz, like an overwhelming warmth, from records and tapes that digital has just never given me. I even have a soft spot for CDs. The artwork feels important on physical media. And the whole ritual of properly listening rather than skipping and shuffling. I’m a bit of a purist that way. And cassettes, in the end, were the easy choice as they’re affordable to make, and they look lovely.

You’ve been collecting records for 25 years. How has your extensive collection shaped your sound, and are there any specific records or artists that had a direct influence on the making of ‘Happy For Now’?

Oh yeah, it’s all ingredients in the pot, isn’t it? I get something out of every record I listen to—even if I don’t love it or even like it. There’s always something worth hearing on there. It all sort of bleeds into what I make. Some of the standouts for me are the laid-back grooves of people like Donny Hathaway, Allen Toussaint, and J.J. Cale. In fact, when I was first demoing these tunes, I played most of them along to drum loops of Zigaboo from The Meters. He’s just got such a great feel. I love getting the practice pad out and drumming along to records by the JBs, Funkadelic, Curtis Mayfield, hoping that a tiny bit of their time-feel finds its way into my fingers.

Then I was heavily into The Beach Boys while writing these songs. I don’t think any of the demos that sounded overtly Pet Sounds made the final cut, but there’s no doubt the influence crept in. I love Pete Dello & Friends’ ‘Into Your Ears’ too. I think ‘Do I Still Figure in Your Life?’ is probably the perfect pop song.

I’m always drawn to fragile, intimate music too—people like Scott Walker and John Martyn were big influences. And that sort of ethereal vibe of Van Morrison’s ‘Astral Weeks.’ It’s my favorite album of all time. There’s just something all-consuming about the atmosphere on it. It hits a spot that nothing else does.

There’s a big chunk of my collection devoted to the weirdos of the world too—people like Annette Peacock, Moondog, Zappa, Captain Beefheart, Arthur Russell, Steve Reich, and Tom Waits. It’s really nice to know that you don’t have to fit in.

What are some of the most interesting records in your collection?

The Artie Kornfeld Tree’s ‘A Time To Remember!’ is the first one that comes to mind. It was his only album, and it came out in 1970 when he’d co-founded Woodstock the year before. It must have been a mad time writing and recording it while making Woodstock happen. It’s never been repressed, and it’s not on Spotify or anything, so it feels like a little hidden gem. You can pick it up cheap though.

And the first I’d save if my flat was on fire would be Annette Peacock’s ‘I’m the One.’ It’s a phenomenal album, and it’s one of those ’70s Dynaflex pressings that are paper-thin and wobbly. But it plays great!

Harold McNair’s ‘The Fence’ is another cool one. It’s a soulful jazz fusion masterpiece, and it’s got a little pink pouch on the front with a pink balloon in it. Unfortunately, the original owner of mine lost the balloon, but the record still sounds awesome.

And my last choice is Love’s ‘Forever Changes’—such a stunning album, and I’ve got an original copy that looks like the original owner never played it once. It sounds absolutely incredible, and I’ve played it plenty to make up for lost time.

Unlikeliest places you’ve found records? Memorable dollar-bin finds?

I’ve hit some real jackpots over the years. I got an original copy of The Beach Boys – ‘Wild Honey’ for £1 at a local fair, an original De La Soul – ‘3 Feet High and Rising’ for £1 at a car boot sale (stacked up alongside the John Denver and Herb Alpert records), and I found an original Miles Davis – ‘Porgy and Bess’ for £1 in a big shipping container at an antiques yard.

Do you still go out and dig through piles of records these days? What are some of the latest finds?

All the time. I was at the car boot sale this morning, actually! No good finds today, but last week I found a copy of Cannonball Adderley’s ‘Inside Straight,’ which is one of the early ’70s ones he made with David Axelrod. It’s so good. I also finally got a cheap original copy of Ronnie Lane’s ‘Anymore for Anymore’ a couple of weeks ago. It seems that most of my choices were released between 1968 and 1974! What an explosive time for music.

What are some future plans?

I’m working on album number 3 already—I’ve got a big batch of 20 or 30 demos on the go right now. I’ve had a lot on my mind lately, so the words are coming thick and fast. I’m just thinking about how to push the sound further—I might get a few collaborators involved this time. We’ll see.

And in the nearer future, I’m super excited to be opening for Dent May in October. He’s such a great songwriter. I actually already had a ticket for the show when I got the call with the support slot.

Thank you. Last word is yours.

As a wise old man once told me at a record fair: “Play it loud and educate the neighbours.”

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Jess and Kieran Logan

Gurry Wurry Website / Facebook / Instagram / Bandcamp / YouTube