Dead Flowers | Interview | Echoes of the Free Festival Spirit

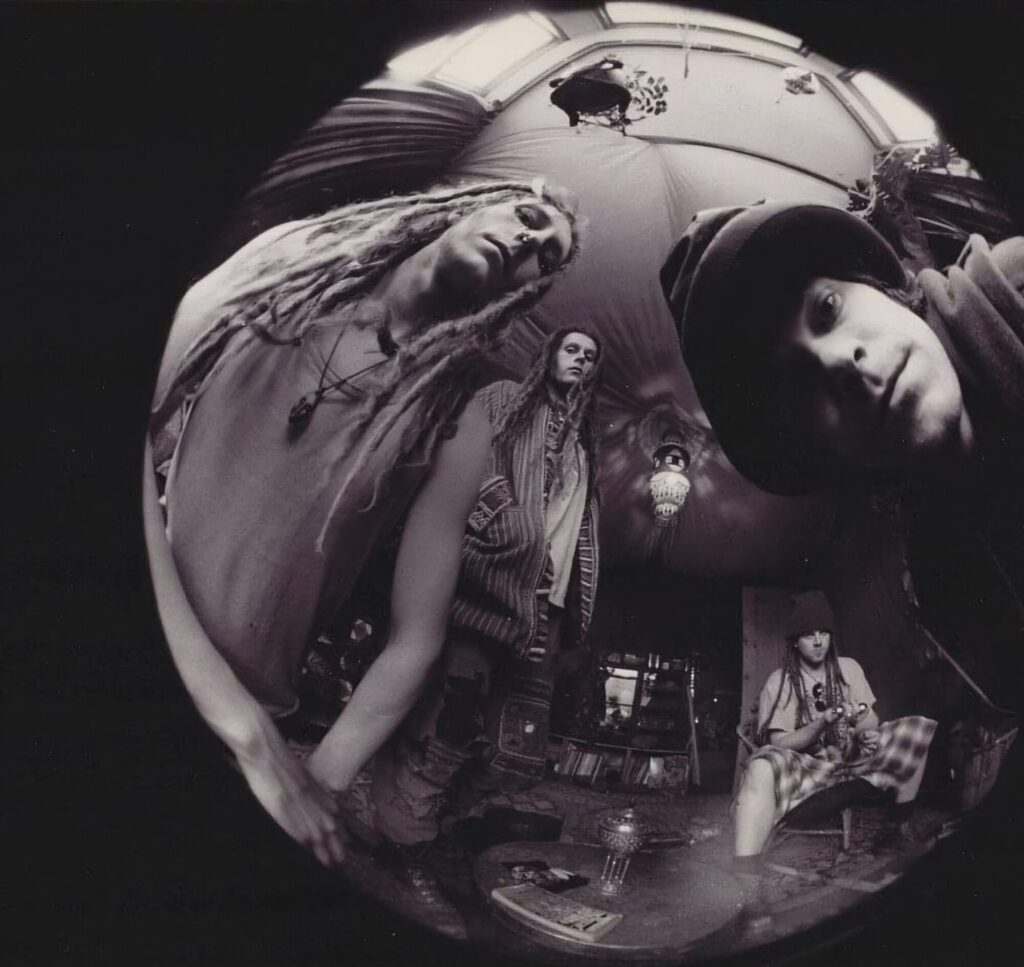

Dead Flowers emerged from the vibrant underbelly of the British music scene, crafting a sonic landscape that felt both familiar and wildly adventurous, like a fever dream you can’t quite shake off.

With a blend of psychedelic rock and gritty post-punk, their sound was a glorious cacophony, echoing the struggles and triumphs of a generation searching for meaning amidst the chaos. Their live performances were electric, weaving a tapestry of sound that left audiences mesmerized, as if the very air was charged with unrestrained creativity and raw emotion. Songs like ‘Chocolate Staircase’ and ‘Thoughtworld’ became anthems for those who sought escape in music, resonating deeply with the lost and the dreamers alike. The band’s ability to navigate through experimental soundscapes while maintaining an undeniable groove showcased their eclectic influences, which included Hawkwind. Just as the sun sets over a city steeped in memories, Dead Flowers carved out a niche that perfectly captured the fleeting nature of youth, love, and heartbreak during that special period of time. Their music was not merely notes and lyrics; it was a manifesto of freedom, a declaration against the mundane. As we revisit their discography, it becomes clear that Dead Flowers was more than just a band; they were a beautiful, chaotic, and essential chapter in the British underground that will never blossom as it did back in those special times.

“I still would not change any of that time and feel privileged to have been given the opportunity to create such great music with great people.”

Would you like to share about your upbringing? Where did you all grow up? Tell us about daily life back in your teenage years.

Steevio [aka Steev Swayambhunath]: I was born in 1955, so I was a teenager in the late 1960s. I grew up in a coal mining town in North East England. Both my grandfathers were miners, and it was a very working-class environment, which could be quite rough, so you had to be able to look after yourself.

My main passions were music, football, and science. My parents bought me a drumkit when I was 11 and an electric guitar when I was 12, but my musical journey started as a drummer. I was lucky that my school friends were into the same things as me, so it wasn’t long before we formed a schoolboy band called Mad Jack. We were also into the same music, like Hendrix, Led Zeppelin, Free, The Groundhogs, etc., and the emerging acid rock and heavy blues rock bands at the end of the 1960s.

Mark [aka Count Spacey]: I was born and grew up in a council house in the North East of England, equidistant between Newcastle, Sunderland, and Durham—a fact that I believe shaped my desire to distance myself from the tribal divides that were an intrinsic part of 1970-1980s Britain, whether that was football-related or part of the many subcultures that it was almost a law to belong to.

My household always had a wide range of music, partly because I was the youngest of four siblings—two sisters and a brother—and partly because one of my uncles ran pubs in Doncaster and used to give us the outdated vinyl singles from the jukeboxes, along with inserts to fill in the holes left by the jukebox mechanism.

As a result, I was able to use a record player before I started mainstream school, and I remember ‘I Am the Walrus’ and ‘Happy Jack’ were songs I loved to put on.

As I grew older, my passions were music, and through my brother and the other kids in my street, I identified as a rocker or, later, a heavy metal fan. I was also into motorbikes and learned to ride when I was around 8 years old, something I did as often as possible until I was around 16. Two accidents caused me to lose my desire for that particular hobby.

Reading was also something I enjoyed and still do to this day, and I think my love of literature was directly linked with music, as I have always wanted music to tell me stories, whether literally or created in my own imagination.

My street had loads of families with kids of various ages, so there were always adventures to be had, even if some of them were not of the savory type. The 70s and 80s were a time of social unrest and division, and it could be quite violent at times, so you had to be on your guard. Being caught in the wrong street, even close to your home, could get you a hiding.

Ferank Manseed: I grew up in the west end of Newcastle and had a relatively normal upbringing. I spent my teenage years daydreaming about fame—I guess that was my immaturity, as I couldn’t care less about that now. Teen spirit, huh?

Was there a certain scene you were part of? Maybe you had some favorite hangout places? Did you attend a lot of gigs back then?

Steevio: We mostly hung out at the local pub (underage drinkers, as drinking laws weren’t so heavily enforced back then), which was also a folk club one night per week. But by age 17, we would go to the nearby large town of Sunderland every Friday night to the Mecca, which had all the best bands of the era, sometimes before anyone had heard of them. It was heaven to us. We saw the likes of Free, Hawkwind, etc., at the beginning of the 1970s when they were just emerging. We actually saw Queen there when they were third on the bill behind Thin Lizzy and a band called Pluto headlining! No one had heard of any of them.

So, my late teenage years were immersed in a rich tapestry of top-quality live music every Friday night.

Mark: As mentioned, I would have been identified as a Heavy Metal/Hippy/Rocker, as I had long hair from the age of thirteen. Although some of the older kids around me were the same, on my particular estate, people my age were more likely to be skinheads or ‘dressers,’ so by the time I was fourteen, I spent most of my time, when not riding motorbikes off-road, in Newcastle, where there was a big scene of like-minded people all centered around the Mayfair Club and the Handyside Arcade (where Club A’ Go-Go once stood, which hosted Hendrix, The Who, and The Animals, amongst others).

Although I was primarily into rock music, I still listened to a wide variety of other stuff like Devo and more “cinematic” music like Japan and Kate Bush.

My first ever gig, at around the age of nine, was at my local village hall, to see a band named Geordie—their singer, Brian Johnson, later became the lead singer for AC/DC.

I saw numerous metal bands at the City Hall and the Mayfair in Newcastle, like the pre-hair metal version of Whitesnake, Kiss, Saxon, etc., and I started going to see local bands, which ignited a desire in me to want to join a band.

I started going to nightclubs and bars at around the age of 14, which gave me access to even more musical influences, from older prog rock to new wave and punk.

Ferank: There wasn’t really a “scene” in Newcastle, so we created one! We promoted a night called “Club God” that specialized in psychedelic, garage, and experimental bands. We did a gig at our favorite bar every two weeks, and every month we held an ‘indoor festival.’ We’d decorate the club all day prior to each gig, with drapes, lights, a teepee, and a freak market selling everything from incense to smoking paraphernalia. Each festival featured about six bands and was really cheap considering—£3.50 for six bands, a bargain. Some of the bands were Nik Turner, The Off Hooks, Mourning After, Dead Flowers, Octafish, to name but a few from the time. The festivals indoors at Riverside Club were always busy and popular with lots of folks.

I remember one of the Club God festivals in particular when a friend came running up and said, “See that guy there in the new biker jacket (points)? He’s drug squad and was at my house when they arrested me.” I asked if he was sure. “I’m certain,” he replied. That’s all the info I needed. I got on the microphone on the main stage and told the sound engineer to turn down the music as I spoke into the microphone: “See him (I point) in the new biker jacket and ironed jeans? Get a good look, everyone. This man is drug squad. Avoid him and be aware of him.” He promptly left, as his cover was now blown. It was hilarious.

Bear in mind, the smoking ban wasn’t law yet, and Club God always had a thick cloud of ganja smoke with just about everyone there indulging! It was stoner paradise when I look back, really.

If we stepped into your teenage room, what kind of records, fanzines, posters, etc., would we find there?

Steevio: Well, the first record I bought at age 12 was the Beatles’ ‘Strawberry Fields Forever,’ and I suppose that set me on my psychedelic journey. I loved the trippy sounds of the Beatles from that era, even though I had no idea about psychedelic drugs at that age. The sounds really caught my imagination, and I read all I could about the hippy movement, filling my bedroom with psychedelic posters. I loved the art, but the biggest poster in my room was of Sonja Kristina from Curved Air! My record collection began to grow at this time, as did the length of my hair—I was a proper little teenage hippy. Every week, I bought an album with my pocket money, and the early 1970s was such an incredible time for music. Everything from Pink Floyd to the Groundhogs, Hendrix to early Black Sabbath, Simon & Garfunkel to Emerson, Lake & Palmer, John Martyn to Edgar Broughton, Cream to Yes—I could go on all day.

Mark: My teenage bedroom was shared with my brother, and the centerpiece was always a Hi-Fi with a turntable and tape deck. There would probably be some Airfix paints lying around from me painting my dungeon and dragon figures, and later, my bass and bass amp, along with a couple of guitars that belonged to my brother. The walls were covered in posters of Kiss, Led Zeppelin, motorbikes, and fantasy art, most likely related to The Lord of the Rings. I was also into drawing at the time, sadly a skill I neglected.

I would often have friends around from some of the nearby estates to listen to music and read Kerrang magazines. A memorable moment was when one of my friends, Jimi Savage, who later became a well-known writer for Total Guitar magazine, was there when my brother played the first Van Halen album. For our generation, this was as mind-blowing as I imagine hearing Hendrix for the first time was for teenagers in the ’60s.

Ferank: My teenage room featured posters from the Sex Pistols, Sigue Sigue Sputnik, and Adam Ant primarily. At the time, I loved Zodiac Mindwarp, and I longed to make “over-the-top” music like he did. I thought he would have had more success by now, but sadly, he hasn’t. There was always a Viz comic and NME handy, and my wall featured lots of torn-out scraps from Viz…

Was Dead Flowers your very first band, or were you involved with other bands before?

Steevio: I was in bands from age 12. Mad Jack was first, then I got a job at age 16 as the resident drummer in a Working Men’s Social Club, where I was backing all sorts of horrible singers. When I went to university in Leeds in the mid-1970s, I lost interest in the psychedelic/blues rock music that was waning, as rock had morphed too far into Progressive and had become self-indulgent. So, I became a punk. The new energy was electrifying. I was in various punk bands up until the early 1980s when the music was morphing into post-punk/new wave. I moved back to the North East, to Newcastle, and the bands I was in became more serious, and we started to release vinyl. The first band was Treatment Room, then Zap, and by this time, I’d moved to bass guitar and stopped drumming. I was using my real name, Steve Oliver, on releases at this time.

Around 1982/83, I became enthralled by electro-funk and started a weekly breakdance club for under-18s called The Sidewalk at Tiffany’s Club in Newcastle. It was the first electro club in the UK, with up to 1,500 teenagers every weekend. Consequently, I bought a drum machine and began making beats. But rather than copy the electro of the time from New York, I formed a band called Acid with some friends. It was like a cross between electro-funk, Led Zeppelin, new wave, and psychedelia. The singer from Acid was the first vocalist of Dead Flowers, Noy Swindon. Acid was fairly short-lived, then came Dead Flowers, and I switched to guitar.

Mark: I joined my first band at age 14, purely because I had a bass guitar (a Burns Flyte). At that time, I didn’t even know what the notes of the strings were, never mind how to tune a guitar. I had to be instructed on what to play by the guitarist saying, “Play the third fret on the thickest string…”

I soon got to grips with playing and self-taught myself the basic fundamentals of music theory, and once I started playing gigs, I was addicted. This band was followed by another band consisting of friends called Shokker. Coincidentally, I still remember playing a gig at Tiffany’s Nightclub in Newcastle, and Steve and Babs, who worked at the Riverside, supplied the PA.

At age 17, my musical tastes started to shift away from metal, and I wanted to do something different. I ended up playing for a band called Catfish Therapy, which was initially more mainstream, but the guitarist and I started to add more alternative/punk influences into the sound. Around the time I was 20, I also started to put on jam nights at The Broken Doll (where Steve and Ferank ran Club God nights). They were pretty raucous, free-for-all affairs, especially during magic mushroom season! Jamming with various musicians from local bands is how I believe I came to Steve and Ferank’s attention when they were looking for a bass player, but they’d have to confirm that.

Ferank: Dead Flowers was the third band I was in. The first was Cats in Black Glasses, and then my Mindwarp rip-off band, Outer Limits—outrageous sexual lyrics, greasy long hair, and dressing like a dirty biker.

Can you elaborate on the formation of the Dead Flowers?

Mark: As mentioned above, I was late to the party, but after a string of stand-in drummers, including Graham Swaddle from God’s Ultimate Noise, we ended up auditioning and securing Carl Moorby as our drummer. I really clicked with Carl, and to me, this was the start of the symbiotic, creative force of the band.

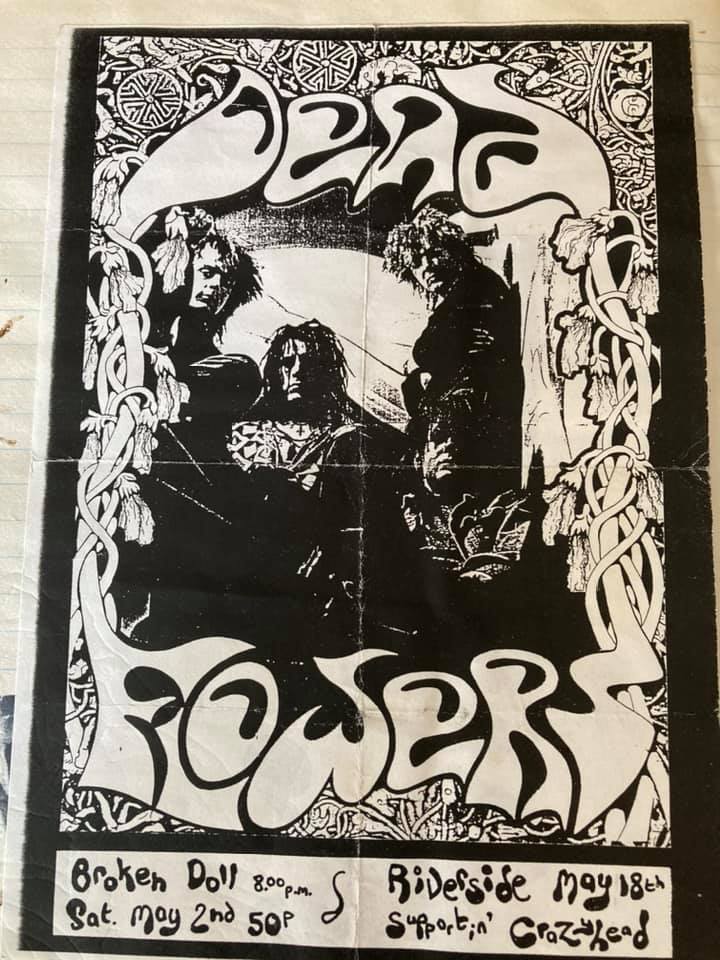

Ferank: Dead Flowers already existed when I met them. At first, I was their super roadie, then manager. They had been given a tour support slot for the Leicester band Crazyhead, and they had a friend filling in as vocalist because the original singer left, as they really wanted to do the Crazyhead tour. I was at a small festival/gathering with members of Dead Flowers and Porkbeast, the bass player from Crazyhead. We played as The Mind Flowers with me on vocals and Porkbeast on bass. I remember we played ‘Red House’ by Hendrix. Not long after that, I was asked to permanently sing for them.

What influenced Dead Flowers’s sound?

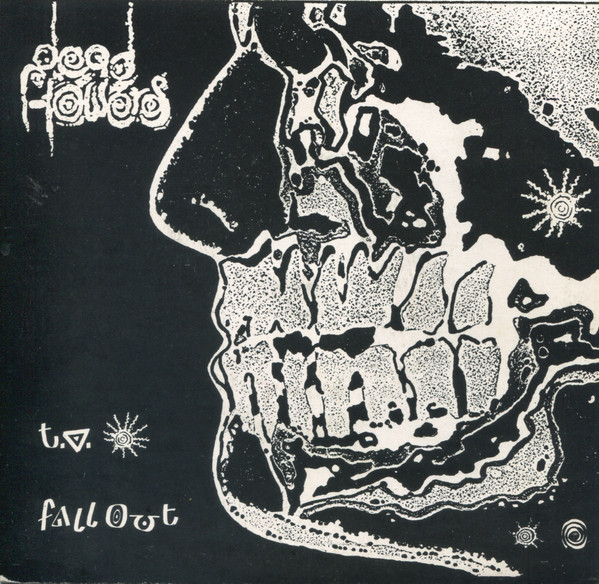

Steevio: It’s hard to know where to start. The initial influences of the first incarnation of the band were the rising grunge phenomena like Mudhoney, plus The Stooges, MC5, but also Led Zeppelin and Hendrix. Those gave us the energy and edge, which is evident on our first and only double A-side 7” single, ‘TV/Fallout,’ on our own Lout Records from 1987. Then other influences began to emerge as the band morphed year by year with new members, etc. Funkadelic, Captain Beefheart, Zappa, Hawkwind, Pink Floyd—everything began to get more psychedelic toward the end of the 1980s, when we really began to amalgamate all these influences into our own sound. My own influences as a guitarist were undoubtedly Jimi Hendrix and Tony McPhee of The Groundhogs, with a smattering of blues.

Mark: For me personally, it was a desire to create music that mirrored the cinematic and layered sounds of Hendrix, Funkadelic, The Doors, and Led Zeppelin at their most psychedelic. But I think elements of Hip Hop, Japan, Kate Bush, John Martyn, and even Bill Nelson circa Be Bop Deluxe were influences on the type of feeling I wanted to instill in people. I think a part of our sound was also influenced by the fact that we were essentially a four-piece band, and we were always conscious of how we could relay our sound to a live audience.

Ferank: So many influences, really. The guitarist wrote most of the songs, and his taste was very varied—MC5, Hendrix, Edgar Broughton Band, Mudhoney, Doors, Jane’s Addiction, etc. He introduced me to some great music that I still listen to. We always performed. Fuck shoegazing performers, which were big at that time. Live, Dead Flowers was great according to others.

What kind of places did you play early on? What are some of the bands you shared stages with?

Steevio: We started out local, of course, in Newcastle pubs, then playing mostly at the club/venue where I worked, The Riverside. It was a fantastic venue, and the promoter, Babs Johnstone, was a legend. She booked all the top bands of the time well before anyone had heard of them. She booked Nirvana for their first-ever gig outside of the USA. We became almost the resident band at times, and we got to support lots of great bands, such as Ozric Tentacles, Spacemen 3, Thee Hypnotics, Gaye Bykers on Acid, and of course Crazyhead, with whom we formed a great friendship and did many gigs and tours. Vocalist Ferank and I also ran a night called Club God at The Riverside, which was aimed at free festival/psychedelic bands—mostly local, but we also had people like Nik Turner and Ozric Tentacles.

Mark: I was lucky in that the band was already somewhat established, so we were already playing gigs outside of the normal local scene, which to me was something I had always dreamed of. We shared gigs with Ozric Tentacles, Poisoned Electric Head, Doctor Brown, Praise Space Electric, The Tofu Love Frogs, The Green Egg, etc., as well as nearly supporting Nirvana!

Transitioning to playing European gigs and some bigger festivals like Hackney Homeless Festival and Nottingham Rock and Reggae, as well as Torpedo Town, were some of the highlights for me.

Ferank: Early on, we played at any bar gig that would have us, really, and we regularly supported bands at The Riverside venue. I remember supporting Nik Turner, Spacemen 3, Jr. Manson Slags, Birdland, Crazyhead, Gaye Bykers on Acid, Dr. Phibes and the House of Wax Equations, The Moonflowers, and many, many more.

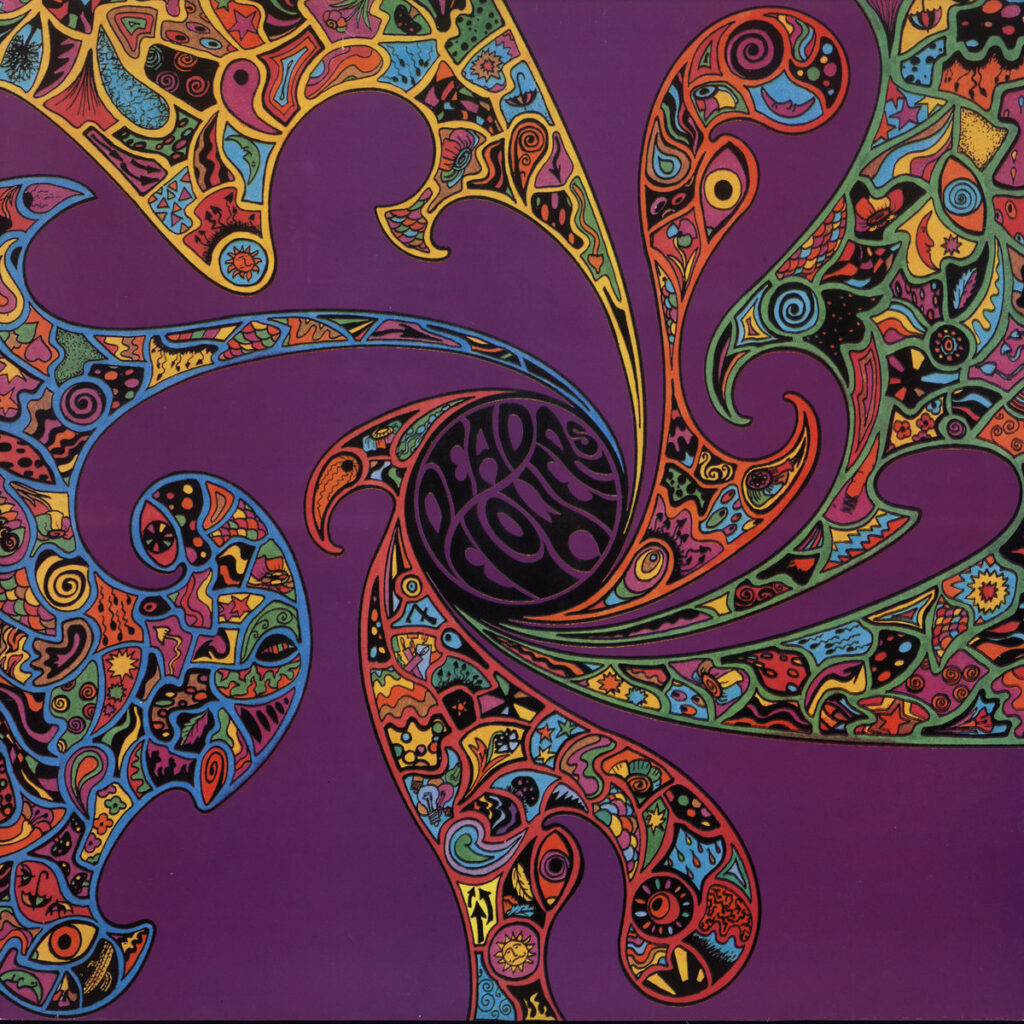

Your debut album, ‘Smell The Fragrance,’ seems to encapsulate a journey through sonic realms. Can you delve into the creative process behind this album? What were the inspirations and influences that shaped its ethereal sound?

Steevio: This album was the end product of four years of morphing from a very grunge-oriented band into an Acid Rock/Space Rock/Psychedelic band, and it coincided with the rise of the Free Festival movement in the UK. A lot of the creative energy of the day was coming from that underground scene, and it wasn’t long before we became absorbed in it. From a personal point of view, I had gone back to my roots as a teenager after years of experimenting with all sorts of different music and several different instruments, but now with a guitar in my hands instead of drum sticks.

I wrote the structure of the music in the band, but I always relied on the rhythm section guys to do their own thing, come up with their own basslines and rhythms, and poet Ferank wrote all the lyrics. Consequently, my influences as a guitarist formed the basic structure of the tunes. I came up with riffs and progressions at home, then brought them down to the practice room for the band to expand on, so everyone was involved in writing the tunes. In many ways, it’s a very raw album. I’d only been playing guitar seriously for a few years, so the grunge/punk element was still embedded in the sound, although it was slowly becoming more psychedelic.

Mark: This was at the very start of my journey with the band, hence ‘Swimming Around’ having the old bass player on it. It was, in some ways, a mixture of various recording sessions. I was just finding my feet with the band and overcoming my imposter syndrome! But I felt we had started to find the beginnings of our groove, albeit with a heavier slant than we would morph into when we found our stoned groove.

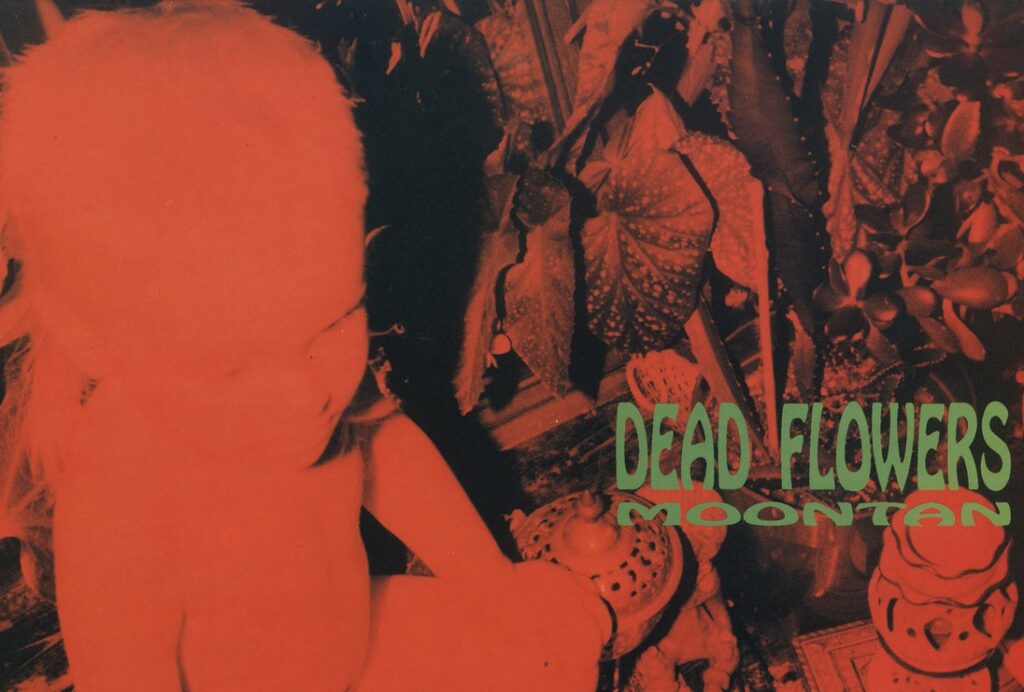

Ferank: Our first album, ‘Smell the Fragrance,’ was a collection of demos spanning our early output. We still hadn’t perfected our sound yet, and to me, it shows. Some great tracks there, though. Everything changed after we made ‘Chocolate Staircase’ on ‘Moontan,’ and that song really defined our sound. Great track.

Tell us about the Mystic Stones label.

Steevio: Brian Sutton, who ran Mystic Stones, approached us, and we jumped at the chance to get an album out. We didn’t know much about the label, and I can’t remember how he heard about us, but there’s some great psychedelic music on the label. If it wasn’t for Brian, we probably would have struggled to get our music out there. I think ours was the second release on the label.

Mark: The main thing I remember was me and Steve going to London and meeting Brian in The Intrepid Fox. Once again, I was fulfilling a dream by finally securing a record deal and having the ability to put music out into the ether. Maybe Mystic Stones was never going to make us successful, but for me personally, this was the opportunity to dedicate myself to making music, and I will be eternally grateful for the funding we received to make Moontan.

Ferank: The Mystic Stones story is a cool one. Club God was going from strength to strength, and a local magazine, The Crack, did a two-page feature on it. Mystic Stones had advertised in NME and said they were looking for new bands. I stuck the pages with Blu Tack so that when you opened the mag, it only opened on the two-page spread about Club God. I scented the pages with patchouli oil and taped a Dead Flowers demo tape inside, along with a letter. The label loved our sound and asked to release an album. They didn’t have a recording budget, but they felt that the demos we’d recorded were good enough to release. So we did. The rest is history.

Moving on to ‘Moontan,’ your sophomore release. ‘Moontan’ incorporates more experimental elements, particularly in terms of song structures and instrumentation. How did your approach to songwriting and production evolve between these two albums?

Steevio: In many ways, we came of age with this album. We’d had a settled lineup for a few years, so we were gelling better as a unit and becoming more competent and adventurous. The writing process hadn’t changed much, but we were more improvisational in the practice room and studio, with everyone coming from their own angle. A lot of that album was improvised; the basic riffs were mostly all we had to go on, then we’d just jam away until we were all in agreement that it sounded good. We were always quite experimental, but as time went on, we drifted further away from grunge and into more intricate structures. The introduction of other instruments also helped make us more adventurous, and the drummer Carl “Chief” had quite a distinctive style.

Mark: To me, this was when I felt like I was truly part of the band and was actually a musician. I now know that the ability to create music organically with other musicians is not something that always happens easily, but we had found that sweet spot of being able to jam together and meld individual parts quite seamlessly.

We also had a stoned awareness of the sonic journey we wanted to send our listeners on due to our own investigations into the psychedelic realms, which I think is very obvious in the production and arrangement of this album.

Ferank: ‘Moontan’ was much more organic and was recorded specifically as an album. Most tracks were recorded live, then we added overdubs, etc. Again, most of the riff ideas came from the guitarists. We jammed really well as a band and rehearsed loads. We would sometimes rehearse in the dark so that you couldn’t see visual prompts for changes, and it just flowed. All bands should try this. I would record our jams, and if something stood out, we used it…

Tell us about the instruments, gear, effects, etc., you had in the band.

Steevio: I started with a Fender Jaguar guitar on the single, which suited the more garage/grunge sound. I’d only been playing guitar in a band for two years at that point but progressed to a Fender Stratocaster once I felt more comfortable with soloing. Of course, it was my hero Hendrix’s guitar of choice. That, along with a Marshall JCM900 and 2 x Marshall 4x12s, a Colour Sound wah-wah pedal, and a Boss DS1 Distortion, was it. Any other effects were added in the studio.

Mark will tell you about his bass setup.

The keyboards in the band were: Andy Charlton on Moontan with a Mini Moog, and Chris Barnett on Altered State Circus with a Yamaha CS80.

Other instruments:

Didgeridoo

Irish Whistle

Also used on Altered State Circus were a Roland TR909 drum machine and an Akai S2800 sampler.

Mark: Transitioning to being a touring and recording musician meant that the gear I had when I joined Dead Flowers needed to be upgraded. Through Steve’s contacts at a local guitar shop, Chris and Andy’s, I managed to get a Fender bass that was brought over on a shipment of guitars from the USA. The shop wasn’t really interested in bass guitars, so Steve got it straight from the shipment, and I bought it for £400. It turned out to be a custom-color Olympic White 1963 Precision Bass, which was used for all the albums, along with a Musicman HD150 amp head teamed with a 300w 4×12 Carlsbro Professional cab. I didn’t use any effects.

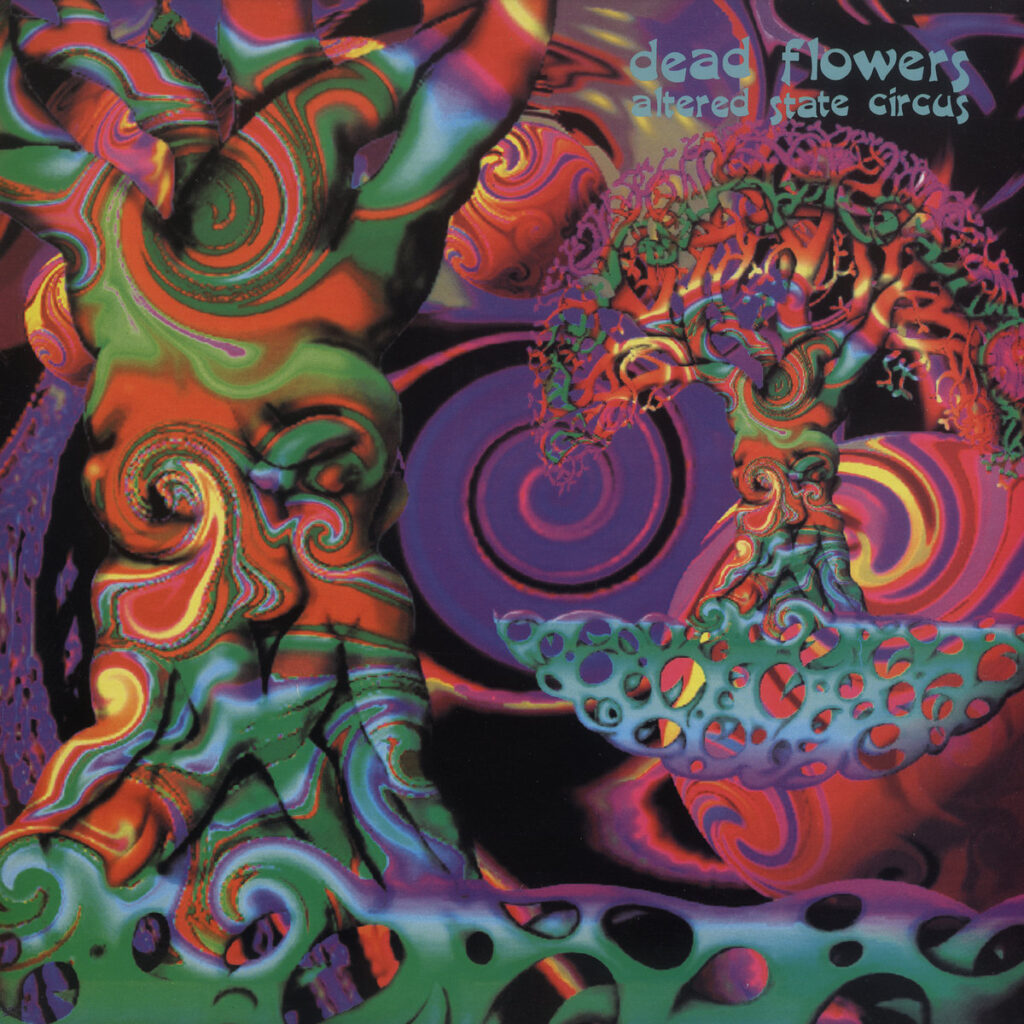

Let’s delve into ‘Altered State Circus,’ your third and final album. It marks a departure from the sound established in your previous works. What prompted this shift in musical direction, and how do you feel it reflects the band’s growth and exploration?

Steevio: Yeah, that album is so spacey in comparison—much more psychedelic, less grungy—and it was probably because we were getting more spaced out ourselves. I know I certainly was. It was the height of the Free Festival movement, and that’s where I spent a lot of my time. We were smoking a lot of weed, but also becoming much more relaxed and competent with improvising.

That whole album was effectively mostly improvised on the spot.

Richard from Delerium booked us into Foel Studios in Mid-Wales, run by ex-Hawkwind member Dave Anderson, where many of the era’s psychedelic bands recorded, for a whole week, and it turned out to be a genius move. We went in there with some basic, very sketchy structures—chord progressions, riffs, etc.—and just jammed away for a whole week. It was so refreshing to do it that way, and in a beautiful part of the world. So beautiful that I eventually moved to a place very near there five years later.

The last track, which only appears on the CD, wasn’t recorded there but in my own studio.

Mark: I think our music was always a mixture of the music we listened to and what surrounded us—almost like the wallpaper to our lives at the time. At this point, techno, rave, and trip-hop were becoming more popular, especially at festivals, where they were the background soundscapes, whereas previously, you would have a mixture of punk, dub reggae, and Hawkwind/Pink Floyd-era psychedelia.

I think the chemicals at the time led to a shift towards more trance-based psychedelia too.

Ferank: When making ‘Altered State Circus,’ we were all experimenting with MDMA and ecstasy, and I think this shows. The best album we made, in my opinion—very hypnotic. A bit “wet” live, though, as these tracks lacked the earlier energy of our previous songs.

‘Altered State Circus’ incorporates elements of electronic music alongside your signature psychedelic rock sound. What inspired this fusion of genres, and what challenges did you encounter in integrating these disparate elements cohesively?

Steevio: I had been getting into electronic music again at the end of the 1980s, after my earlier flirtation with electro, and by 1991, I was totally besotted with techno. I’d started building an in-house electronic music studio, and by the time ‘Altered State Circus’ came out, I had already released my first Acid Techno record as 3000003. I had an Akai sampler, so after we’d recorded the album, I sampled the whole band—just little hits of odd drums, basslines, and vocals, but no guitar. Then, using the kick drum of the techno drum machine of choice, the Roland TR909, and samples of the ubiquitous acid machine, the Roland TB303, I crafted the whole rhythm from scratch and layered everything on top. Delay effects came from a Roland 501 Space Echo. It was my first-ever attempt at sampling, and I actually found it quite easy to put that track “Vodaphone in Oz” together. Strangely, I’ve never done another totally sampled track since.

I think it was a nice way to end the album, as it was the end of my era in rock bands, and I moved onto electronic music, which I still do to this day. I never picked up my guitar again.

Mark: As stated, the shift in the music scene probably influenced us subliminally, and the fact that we did not limit ourselves sonically meant that the addition of electronic elements was not something that was considered; it just happened as a natural progression. Our writing and recording style of allowing everyone to express themselves as they wished meant the transition was pretty seamless and organic.

I suppose there was the added element of the delays, etc., needing to be in rigid tempos. For instance, ‘Warmth Within/Chemical Binoculars’ has three different tempos in the various elements. In the past, we would probably have recorded the drums and bass first with a guide guitar track, but for this song, we had to record each element separately to Steve’s delay tempo.

Were you part of the so-called UK Free Festivals movement? There’s a fantastic book called Festivalized: Music, Politics, and Alternative Culture by Ian Abrahams & Bridget Wishart. Would you like to elaborate on how you view the scene from today’s perspective?

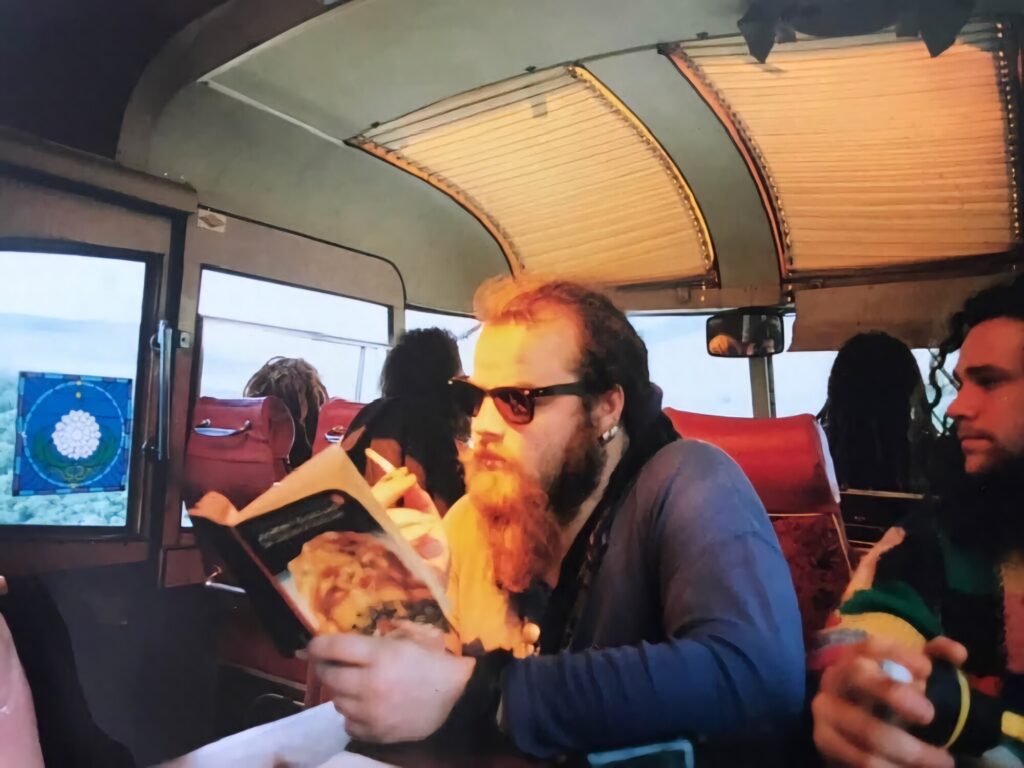

Steevio: We were definitely part of it, and I was personally, in quite a big way, as in 1988 I bought an old 1950s bus with the intention of traveling to the festivals with my partner and our kids. We ran a vegetarian/vegan café from it. It doubled as a tour bus for the band at times. Dead Flowers played at some, but not that many, although we once played at Glastonbury on a travellers’ stage. I went to my first free festival in 1985 and was immediately hooked. I continued being involved until the mid-1990s when it started to become difficult with the police clamping down on the travellers. It all came to a head at a festival called Torpedo Town in 1992, where Dead Flowers played, and at one point I got separated from my partner and the kids by riot police, so we tended to travel in France and Spain from then on. The music was very eclectic at those festivals—psychedelic music, punk, through to techno and acid house. They were very colorful times. I can only look back on those times as transformative and with much fondness.

Mark: If you didn’t live through the times leading up to the festivals, I don’t think you would realize the significance they played in defining a generation. The economic and political situation created from the ’70s onwards, and then the capitalist boom of the ’80s, saw large sections of society left behind. Especially in the south of the country, young people had to choose between living in slum housing in poverty or going out on the road and finding a community that offered some sense of optimism.

Like anything in life, it wasn’t perfect, but I can see why it appealed in the day. Also, housing in the north of England was still affordable in those days, so I don’t think there was such a need to set out on the road and deal with all the problems that brought.

As the rave scene expanded, it slowly but surely infiltrated the free festivals. I distinctly remember being at Bala Free Festival in 1991, and people were complaining about the Spiral Tribe sound system being quite disruptive. Fast forward a year, and rave was assimilated into the scene totally.

The breaking down of previous tribal boundaries that had existed is something that people may not now appreciate. All of a sudden, your former punk crusty was dancing with some middle-class inner-city ravers, and everyone felt a sense of belonging and love. It actually felt like we could change the world for the better.

The popularity of it all was actually what brought about the demise of the free festival scene. Maybe there was some truth that a dramatic shift in consciousness was occurring, as the right-wing government of the time had emergency meetings to try and outlaw a scene that was taking over whole generations of the country. That may seem whimsical now, but the fact that they see divisiveness now as a form of political control does make you wonder.

Ferank: Yes, we often attended free festivals but only ever really played at one in Torpedo Town. It’s rare that all members were present at a festy; I regret this now, as I often couldn’t make it. The scene couldn’t really be the same now, sadly. It was all pretty lawless, and there were lots of drugs openly sold…

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band? Which songs are you most proud of? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

Steevio: That is a very difficult question. I enjoyed most, if not all, of those times, from the early days until we packed up our gear for the last time. The other guys will all have different favorites, I’m sure. I can’t really pick a favorite song; I love so many of them—probably something off Altered State Circus.

Again, with gigs, many of them were great. I remember a fantastic gig we did with Ozric Tentacles at Cambridge University, and another we did with Dr. Brown in Portsmouth, I think. Some gigs we did with Crazyhead, but it’s all a bit of a blur now.

Mark: I love every aspect of playing, writing, and performing music anyway, but I also loved meeting people and traveling. I like to think we were good people. In the UK, we never had accommodation when on tour, and I can count on one hand the number of times we were stuck for somewhere to stay. Ferank would usually just ask when we were on stage if someone could put us up, and it always seemed to work. What was even better, though, was that when we returned to the same town, we would always get invited back.

I do not have favorite songs for any music I like; it would depend on how I feel on a particular day and what I want to get out of music at that point. My stepdaughter, who I never tried to influence, says to this day that “Gaia’s Love Hole” and “Feed It” are two of her all-time favorite tracks, so I will let her answer that one.

My most memorable gig, among many, has to be when we played in Milan. The Italians loved us and I think thought we were universally popular, proven by the fact that in the previous weeks, Nirvana and the Red Hot Chili Peppers had played at the same venue. Unselfconsciously, there was a consensus that we had totally blown them away as a live act! In their defense, I think both bands were going through dark times (it was not long before the demise of Kurt), and we heard rumors that the Mafia had cut the supply of weed and flooded the market with heroin, which probably wasn’t conducive to tight performances if you were that way inclined. We also met an artist, Carlo Pianco (Charlie), who was a collector of psychedelic music and later put us up at his place in Cademario—a story for a different time!

Ferank: I loved being in the band, and song highlights for me are ‘Thoughtworld,’ ‘Chocolate Staircase,’ ‘The Elephant’s Eye Was Eerie,’ and ‘Jesus Toy.’ No gig really stands out to me; they were all cool.

What occupied your lives and the lives of other members later on? Were you still in touch with other members? Is any member still involved with music?

Steevio: We kind of went our separate ways. I moved to Wales 25 years ago, but I’m still in touch with Mark (Count Spacey), Ferank, Trevor, the original drummer, and I still have contact with Psilosimon, the original bassist, Wildy, the drummer, and Noy, the original singer. I’m not sure who is doing what musically, but I know many of them are still doing stuff. I’m still playing out live and releasing improvised electronic music under the name Steevio, with my wife Suzybee, who does hand-drawn animated visuals. We run the annual Freerotation Audio Visual festival and the Mindtours record label. I hope you can get something from that, and thanks again for the interest!

Mark: I actually felt a bit depressed after the band folded. I was quite burnt out and totally broke financially. I did not play music for a good ten years, but I did keep in touch with Ferank. Steve moved to Wales, and Carl moved to Brighton, so I lost touch. However, I went to Steve’s wedding last year, and it felt like I had only seen him yesterday. I actually did some DJing with Ferank at a bar called Popolo, where we would play really obscure covers and push people’s musical boundaries!

I ended up getting back into playing when my brother’s guitar teacher asked me to play in his cover band as they had some gig commitments. This made me realize how important music is to my psyche, even though I am not a fan of cover/tribute bands. I then answered an ad for a bass player, and when I went to meet the guy setting up the band, it turned out it was two people from my previous band Catfish Therapy. We played a few gigs and did some recording, and I was just glad to have a musical outlet. Through this, I made a connection with the drummer John Rowe, who is a dance music producer and artist as Odic Force. We now record at his home studio as a purely cathartic exercise; the process of having no agenda to what we do is very liberating. We have some of our unfinished projects on SoundCloud as Count Spacey and the Voodoo Flame, and we have too many other recordings that we still need to complete!

Ferank: After Dead Flowers, I continued making music and supplied vocals for tech house, hip hop, jazz, trip hop, etc. Steevio (guitarist) now makes analogue techno, and the bass player is still in bands. I lost touch with the drummer and the keyboard player, so I can’t speak for them. Sadly, in 2016, I had a stroke that nearly killed me! I’m now stuck in a wheelchair, and the whole of my right side is paralyzed. I’m pretty much a hermit these days and rarely leave the house…

“We recorded and mixed five songs in eight hours and used it as a chance to explore some musical ideas”

Is there any unreleased material by Dead Flowers or related projects?

Mark: I uploaded some tracks to YouTube that we recorded for a guy who wanted to be a manager for us. We recorded and mixed five songs in eight hours and used it as a chance to explore some musical ideas. They were done on the fly, so they are very different from what we would have usually put out. This is where we first recorded ‘Chocolate Staircase,’ which basically came about by Steve jamming the riff at the beginning in the studio, and all of us joining in. They are on my YouTube channel, Mark McIver.

Ferank: Regarding unreleased material, I have a videotape somewhere of a Dutch tour that one day I would like to convert from video.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Mark: There were many disparate elements that combined in the demise of the band. For instance, ironically, the burgeoning rave scene meant that venues that would have formerly booked us now would favor putting a DJ on, guaranteeing a full house of pilled-up punters. Even more ironically, this would also lead to the demise of many venues that relied on alcohol sales to keep them afloat!

I wish we had made the next step and could have actually made a living from the band, but the truth was that we never made a penny personally from Dead Flowers. I still would not change any of that time and feel privileged to have been given the opportunity to create such great music with great people. Peace and love to you all.

Klemen Breznikar

Dead Flowers Instagram