Donovan’s Brain | Interview | New Album, ‘Fire Printing’

Donovan’s Brain, birthed from the gritty, rebellious essence of the ‘80s DIY scene, has weathered countless storms and undergone endless transformations. Their latest sonic experiment, ‘Fire Printing,’ emerges like a phoenix from the ashes of their storied past, a testament to their relentless evolution and undying spirit.

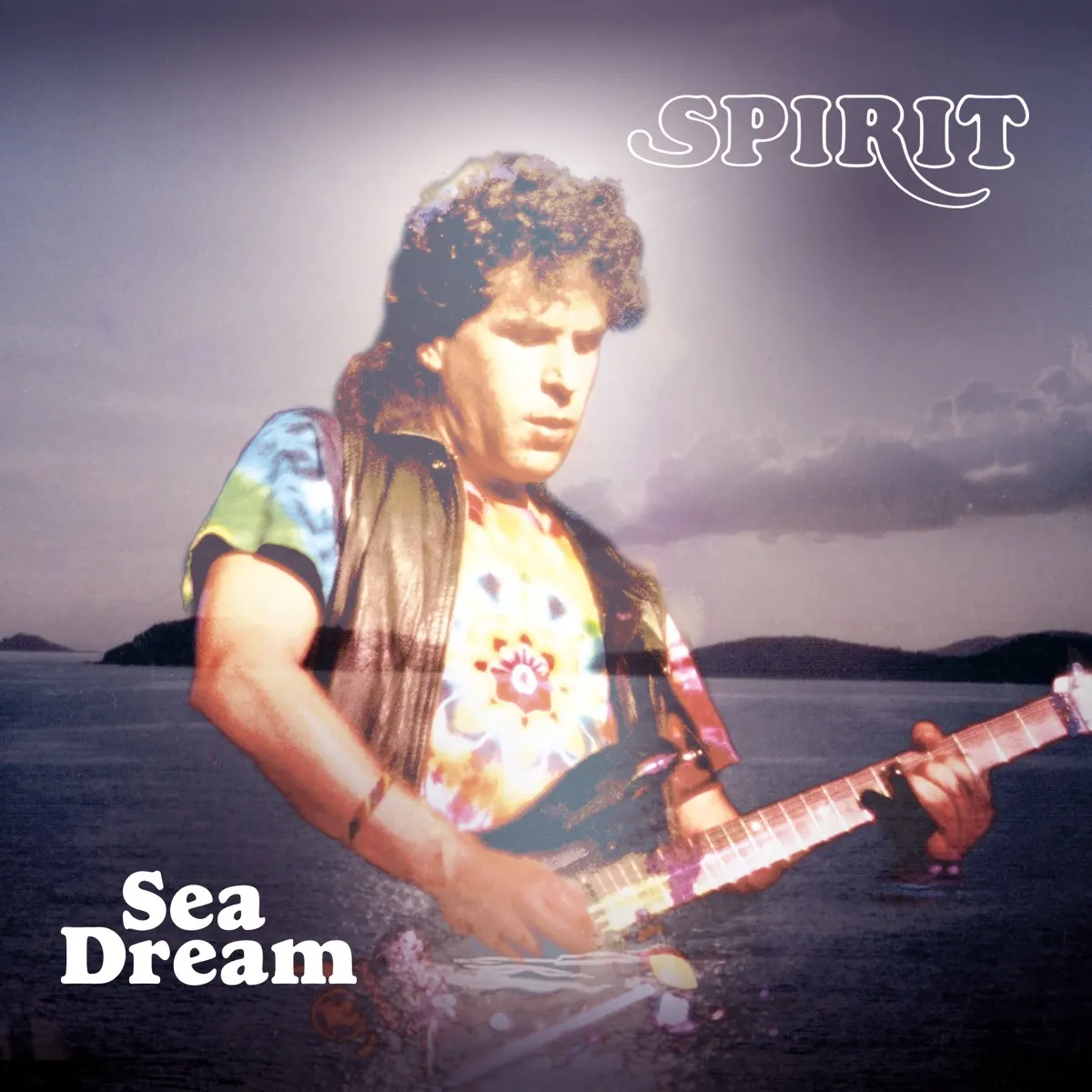

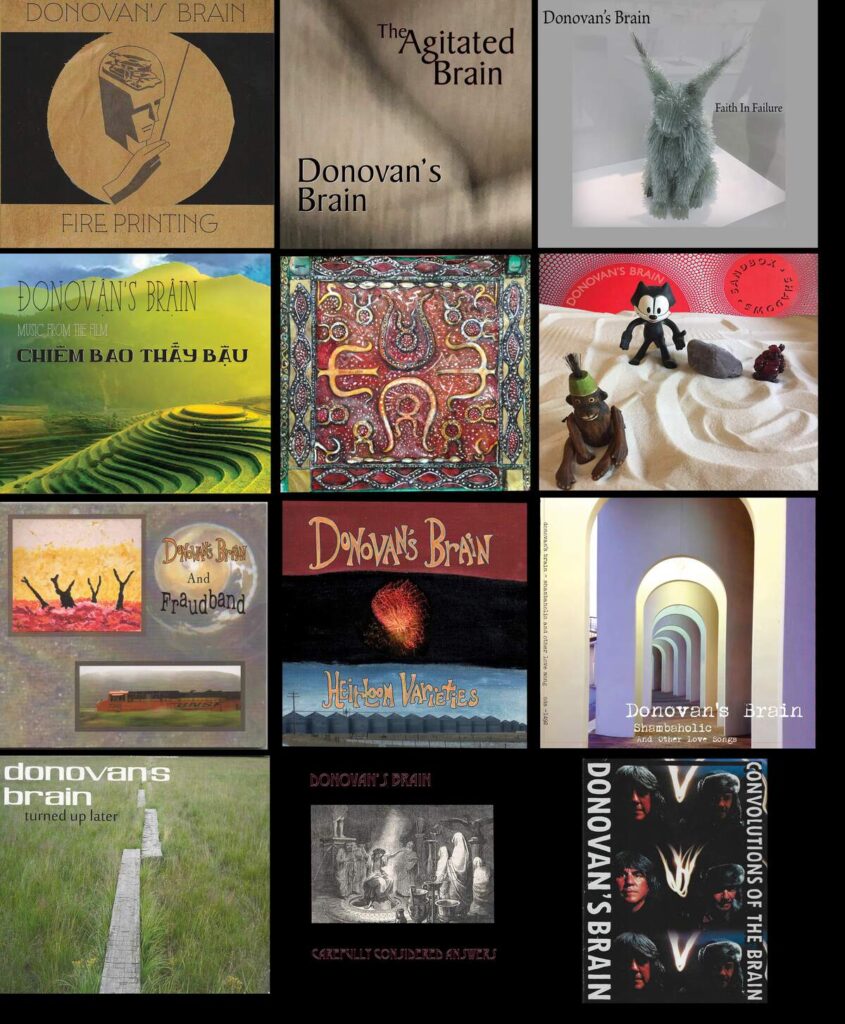

From the raw, psych-infused brilliance of ‘Shambaholic’ to the sprawling, 60s-tinged opuses of ‘Great Leap Forward,’ their discography reads like a map. The recent ‘Fire Printing,’ with its fresh lineup and pulsating energy, marks a new phase of audacious reinvention, while the shadow of Bobby Sutliff’s absence looms large, a poignant reminder of the band’s turbulent yet triumphant journey. The swift release of albums like ‘Fire Printing’ shows their unyielding drive to churn out raw, visceral tracks, even as they grapple with the tumult of constant change and collaboration. Their ongoing projects and potential live shows hint at an unquenchable thirst for more, a restless energy that refuses to settle for the status quo. Meanwhile, their exploration of both new and old music demonstrates a relentless quest for authenticity amidst the ever-changing tides of the industry. Donovan’s Brain continues to embody the spirit of musical rebellion, a testament to their enduring passion and unyielding pursuit of creative freedom.

“The title ‘Fire Printing’ came from a dream.”

Let’s start at the beginning. Ron, could you take us back to the early days of Donovan’s Brain? What inspired you to form the band, and how did the initial lineup come together?

Ron Sanchez: A little background is probably needed. I grew up in San Jose, California. I started playing in bands in 1964 or 1965. There was a very active local scene happening around us: Syndicate of Sound, Chocolate Watchband, Otherside/Bogus Thunder, Mourning Reign, Stained Glass, and more. There were a lot of out-of-town bands coming through, too. Of course, some of the bands now have gained a sort of mythical status. At the same time, our close circle of friends realized there were records to be found. By 1966, I was a very serious record collector—that is, on the limited budget I had. We also found out that we could order records from the UK. My older brother’s friends were pretty hip. They told me about Rave magazine from London, and we’d get the KYA Beat, a local West Coast newspaper put out by a favorite radio station.

All this meant I was discovering bands like Pink Floyd, The Move, Mighty Baby, Action, Alan Bown Set!, on top of The Who and such. In 1966, I saw Jefferson Airplane for the first time. The Yardbirds, too. In 1967, it was like a tidal wave. We went to the Magic Mountain Music Festival in 1967. This was a sort of test drive for Monterey Pop. The lineup was just amazing. Besides The Doors, Airplane, Byrds, and Country Joe, we saw Kaleidoscope with David Lindley, Captain Beefheart with Ry Cooder, The Seeds, Tim Buckley, PF Sloan, Mystery Trend, and more.

In 1968, I talked my way into the local underground radio station. They sussed out that I had a load of records they didn’t know and let me in to help out. Our band had figured out how to record with some basic gear. All these things that I was into came together while I was in high school. By 1970, I realized that playing in a band was not going to take me anywhere. We could play, but no one was writing songs. For me, that was a big deal. I didn’t want to play in a bar band doing other people’s songs. Some of my contemporaries were happy with that. I decided radio was what I wanted to do and sold my guitars and amp.

Radio turned out to be a good choice. I could influence what was played, and I could meet bands. Of course, it was the unknown UK bands that I wanted to meet. They were happy to find someone who knew their music in the States. The labels were happy to give me access and tickets and stuff. Seeing good musicians up close, working together was an eye-opener. The bands I’d played in seemed pretty lame in comparison. I was directed to Andrew Lauder at UA in London by Greg Shaw. That was another huge step. That’s when I met Man, Help Yourself, Hawkwind, and all those bands. I got a job at the best record shop in San Jose at the same time. It’s here that I met Roy Loney, Cyril Jordan, Jud Cost, and Scott McCaughey. Our lives would stay connected over the years. Very important.

At the end of the 70s, it became apparent that commercial radio had lost the thread. Throughout the seventies, I moved around the Bay Area, working in record retail. The industry was not interested in art anymore. It was all about selling 5 million copies of Saturday Night Fever. I took the hint and packed up all my belongings and moved to Montana to open a restaurant. I needed to get out of the record business. I got a radio show at the university and settled in.

One day in 1984, I looked in at the guitar shop and spotted a late 60s Danelectro guitar. It was similar to the one I’d seen Jimmy Page play with the Yardbirds and Led Zeppelin. I bought it just to have a guitar in the house again. A couple of years later, I invited a couple of friends over to play. Jim and Colter would both later become part of Donovan’s Brain.

There was a very lively scene here in the late 80s. Indie sort of bands, including the very first incarnation of Steel Pole Bath Tub. At some point, I decided I was ready to try forming a band once again. There was a moment when three of the popular bands split up. I asked Kels Koch and Jim Kehoe if they wanted to put something together. Another musician, Paul Rose, suggested he could be our drummer, though I knew him as a guitar player. The Nomads were a big influence on me at the time. I put together a list of old 60s songs I’d played and some modern things like Johnny Thunders, Alex Chilton, and The Soft Boys. Our gigs went down well, and we had a little following. It didn’t last long. I think Kels moved away. The thing is, we still didn’t have any original material. I continued to play with some of the same people in various one-off things.

Recording was clearly something I wanted to do. I had plenty of radio production experience, so I knew my way around a studio. I quickly went from a 4-track cassette to 8-track. It was just learning how to write songs. I finally came up with one that I knew was exactly what I wanted to do. ‘50,000,000 Years Before My Time’ got released on a cassette. To me, that was the real start of Donovan’s Brain. The first full album, ‘Shambaholic,’ was completed in 1994. I’d managed to pull all those influences together. Now it was a matter of finding a group of musicians who could play these songs….

The recent loss of three core members of Donovan’s Brain must have been incredibly challenging. How did you navigate these losses, both personally and within the context of the band’s creative process?

Well, we’d already lost Richard Treece and Ken Whaley. In both of those instances, it was clear their health issues were fatal. I was pretty close with Richard. I’d brought him out to Montana twice. He also played with us at the Seattle Terrastock. That was a big deal for all of us. Tom Stevens died suddenly in January 2021. I’d just talked to him about the work I had for him on songs for ‘Sandbox Shadows.’ He’d been busy with The Long Ryders, so I was waiting for his time to open. He said he was ready to do the work. Four days later, he died at home while waiting for dinner. That hit us all hard. I got the news early on Sunday morning. I walked down to the studio and wrote a piano piece for Tom. That song would appear on ‘Chiêm Bao Thấy Bậu’ twice as ‘I Would Not’ and ‘Story In A Story.’ Writing some music was all I could do. I shared the song with Bobby Sutliff, who just said he’d have to wait a year before he could consider working on it. He’d just met Tom the year before when Long Ryders played in Ohio. I think he was pretty shaken up. I know Scott Sutherland was, too.

Tom brought a lot to the band. Of course, he was a great bass player. He also had a fantastic voice and played guitar. He was involved in the production and mixing, too. He always had a good idea or a bit of advice. That talent was irreplaceable.

Joe Hughes, Kris’s husband, agreed to step in to finish those bass parts. Scott, Bobby, and I all considered ourselves capable bassists. Tom was in another league. Joe is a skilled player, too. It was a small comfort to have someone who could step up and fill the ranks.

Ric Parnell was a well-traveled rocker. When I first told Deniz Tek I’d met Ric and he’d done a Brain session, he sort of rolled his eyes. “Oh, Ron’s found another old British guy.” Shortly after, Mark Taylor from the Lipstick Killers happened to ask Den who was in the Brain these days. When Den told him Ric Parnell, Mark fell on the floor. Really. Den came back and asked if Ric could do some work on his own albums. Right from the start, I knew we might not have Ric indefinitely. He had lived a hard life. Knowing that, I encouraged everyone to submit songs so we could get Ric on as many as possible. Ric was happy as he got paid by the song. Playing drums was his only source of income, and he wasn’t getting much work otherwise. The last two times Ric was here in 2021, he was clearly in decline. He was depressed, too. His best mate, John Goodsall, had died. He was living on the edge and felt underappreciated. The last two sessions he did were in the winter of 2022. We needed some work on the soundtrack and had some other songs for him. A few weeks later, he called and desperately needed rent money. I pulled together a few more songs for him. These last two sessions were done in Missoula, where he lived. The severe Montana weather made it impossible for him to travel the 210 miles to Bozeman. To be honest, we were also afraid he’d die on our couch. That wasn’t an exaggeration. It was just a few weeks later that he went into the hospital.

By my count, Ric recorded about 150 songs for the Brain, Kris, Tom, and Deniz Tek. After he died, I took inventory of what I had in the archives with Ric. There were a number of songs that we never finished for one reason or another. I would eventually rework some of these. A couple can be heard on ‘Fire Printing.’ This was my way of dealing with his death. Music therapy. It was ghostly hearing Ric playing for months after he’d left us.

In May 2022, Bobby Sutliff finished a solo album he’d started five years earlier. I didn’t think he’d ever get it done to his satisfaction. I helped him a little. I found a couple of things that were started as Brain songs. I got those back to him. I also rounded up every demo and fragment he’d sent me over the years. In return, he’d give me tracks he wasn’t able to finish. If he didn’t have words when the music was written, he would discard the songs. I had no problem writing words to his music. He’d just given me a couple of pieces. That summer, Bobby went quiet for a couple of weeks. I called to check on him. He said he’d been having some medical issues and was going to get them checked out. Nothing seemed that serious. Two weeks later, I called again but got no reply. That was on a Friday. On Sunday morning, his wife Wendy called to tell me Bobby had been diagnosed with stage four cancer. There was a moment when they thought there was treatment available. That wouldn’t happen. His condition deteriorated over the next two weeks, and he was gone.

We flew out to Ohio to meet up with Tim Lee from the Windbreakers and John Thomas, one of Bobby’s childhood friends, to bury Bob. That just didn’t seem real.

I came home and fell into a deep dark funk. I had to finish ‘Faith In Failure’ and then decide if the band could continue. Scott Sutherland and I talked about it. We knew we could find some players to record. Finding partners like Tom, Ric, and Bobby seemed like an impossible task. What I did was write some new songs. Some built on salvaged drum tracks, and some new from the ground up. There were several visits with my therapist, too. I cannot underestimate how helpful that was. She knows music is my life and the band my identity.

Scott and I could not have predicted how we were going to rebuild the band.

‘Fire Printing’ has been described as a “trip in three movements.” Can you delve into the conceptual framework behind the album and how it evolved during the recording process?

The title ‘Fire Printing’ came from a dream. In my dream, someone said, “That’s called fire printing; nobody does that anymore.” Of course, I wrote this down. A lot of my songwriting comes from dreams. This bit was too strong. I initially resisted calling the album ‘Fire Printing,’ but I couldn’t shake the idea. Nothing better appeared, so that was it.

One of my skills is working out the running order for our albums and for others. I think it’s an offshoot of being a radio DJ. Put in the proper order, the songs can tell a story or take you on a musical ride. An album has two sides, or four, or whatever. Each side should have a beginning, a middle, and an ending. And then getting from the first song to the last song should have some sort of arc. CDs have destroyed the art of programming an album. Streaming has wiped the idea from the listener’s consciousness.

Back when we were working on what became ‘Sandbox Shadows,’ we had a lot of songs—26 or so. At one point, I made a mock-up of a 13-song album. Bobby said, “No, that’s too many.” I took that advice, and we ended with two 10-song albums: Sandbox Dispatches and Two Suns Two Shadows. I released them in one package. Otherwise, it would have pushed our schedule too far into the future. The same thing happened with ‘Fire Printing.’ At the beginning of last year, I put together the songs we had to see what sort of album was possible. I think that was 13 songs. When Joe Adragna came on board, several more songs were written. I asked Joe to submit some songs. Scott had a burst of activity, too. I had to make some choices. I couldn’t hold back any of Scott’s songs this time. He had some strong material. That was five songs. Joe had two. I had a bunch and wrote two new ones for the album. That meant dumping some of my songs that had been on the original list. I could only whittle it down to the fifteen songs heard on the album.

So what do you do with 15 songs? ‘Paper Pilots Pushing’ was meant to be the opening song on ‘Faith In Failure.’ At the last minute, I decided it needed more work, so I pulled it. The remake worked out well, so it regained the opening position. I think Joe’s song ‘The Drumshanbo’ was always meant to close the record. Now it was a matter of working out the middle. The three-movement idea was in place, so I knew the shape. I’d need to spread Scott’s five songs across the three sides. I finally saw that the songs could move from rockin’ to very heavy, with Side Three having some weight. There are three songs about death and dying on the album. This wasn’t planned. The songs cover a lot of styles. The trick was to make sure it sounded like one band. You get a taste of all the things we can do in 69 minutes.

Side One is the introduction to the new band. Side Two is the tuneful core of the album. Side Three is the hammer. By the end, you know you’ve traveled somewhere with Donovan’s Brain. The movement titles are my own sense of humor. You can make of it what you want. We are serious about what we do. We just don’t take ourselves too seriously.

With the recent lineup changes, how did you approach the task of integrating new members into Donovan’s Brain? What qualities did Scott Sutherland, Joe Adragna, and Kris Wilkinson-Hughes bring to the table?

Kris and Scott have been on board for several years. When Bobby and I had to rebuild the band in 2010, Scott was the first addition Bobby suggested. Scott had worked on the Roy Loney album I produced. Bobby was on that too. I think it was a brilliant idea to get Scott. He’s been a prolific writer. He fell into the George Harrison slot, getting two or three songs an album. I corrected that on the new album. Scott is younger than me. Despite that, we speak the same musical language. He understands what the Brain sound might be. He plays in some other bands that are very different from Donovan’s Brain. All of us—Kris, Joe, Bobby, and myself—are fairly self-contained. We could make albums on our own and have. Everyone understands that when a song is presented to this band, we all can take a shot at it and offer ideas.

I love Scott’s twisted view. There is a strong sense of humor and sarcasm running through his ideas. He is also thoughtful and sometimes dark. When I put the second Donovan’s Brain together in 1995, it was meant to be a songwriting roundtable. Over the last few years, we have achieved that goal. Scott has been crucial to this. He can listen to my small suggestions. He’s set high standards and makes me work harder.

Kris was an old friend of Bobby’s. He knew her from Jackson, MS. Kris and Bobby had sung on the album Matt And Tim’s Paid Vacation. I asked her if she’d like to lend a hand. She’s got her own band, My Girl The River, that takes most of her time. I try to find songs that she can add to. We’ve collaborated on several songs. She sees things in her own way and comes up with great ideas. ‘River Of Tears’ on ‘Sandbox Dispatches’ is a good example. I had the verses written out. She rearranged them and wrote the chorus, which took the song to a higher emotional level. Singing that duet with her was a test of my abilities. That would be one of the best songs we’ve done. It’s built on Bobby’s riff, my tune, Tom on bass, and Matt Piucci on guitar. When I said Fairport Convention, everyone knew what I meant. A female voice has always been a part of the Brain. Kris brings us more than just a voice. She’s a songwriter and finds that idea you never imagined.

We have to thank Scott McCaughey for bringing Joe Adragna into the fold. I’ve known McCaughey for a very long time. We first met in 1972. He encouraged me early on to take the band seriously. I did a session in Seattle at Egg. Jim Sangster offered up The Young Fresh Fellows to provide the backing. YFF joined us again for a recording session here. Scott sat in with us at Terrastock. He never rehearsed with us. The band had no idea who he was. Once again, he dropped in and sent Donovan’s Brain off in a new direction.

Scott asked if I had a drummer. I reminded him that we didn’t, as he’d just died. Scott recruited Joe as the drummer, but he added bass to ‘Hey Bobby!’ as well. When I asked Scott if Joe would do more with us, he just said to ask him. I did. I sent him one of my more difficult songs, ‘Stranger In The Light Of Day.’ He nailed it. At that point, I knew he was the man for us. I spelled it out very clearly. He was being offered full membership in the band with voting rights. He has his own band, Junior League. I know he can write and sing. Joe gladly accepted the offer. It turns out he is a big fan of Scott Sutherland’s work in Model Rockets. They connected straight away. He ended up working on about half the album. His songs arrived virtually complete. I added a few touches and suggested small arrangement ideas. Joe started working with us in June 2023. The album was finished by the end of the year. He couldn’t believe how fast we’d completed an album. I had to remind him we’d been working on this album for a full year before he showed up. Right away, I knew we were on to something special. I ditched three of my songs to make room for the new songs. It’s a varied mixture and sounds fresh. The new songs fit in well with the older pieces with Ric. A testament to Joe’s skill as a drummer.

Joe knew he was filling some big shoes. He’s a fantastic drummer. I didn’t know if I could ever be happy with anyone after Ric. We’d had good drummers in the past. Ric understood songwriting in a way the others hadn’t. Joe, being a songwriter, can see the structure of a song, not just as 4 bars of 4 beats. Our first round of writing for the next album has gone well. Scott had offered up a new one. After reviewing it, I asked Scott if he had a Dobro for the rhythm part. Joe reacted to that update and asked to do another pass at the drums. He suggested a bit more Ringo, so I went Billy Preston on the piano. That all went down in just a few days. It felt like a real band again.

Joe is a fan of the 80s era Bobby came out of. ‘Sunset Heart’ on the album fills that jangly part of our sound. I’m sure he had written the song before he joined The Brain, so it wasn’t a conscious effort to replace Bobby at the songwriting table. It’s just part of his own sound. He can do the heavy stuff too. He plays a lot of guitar and bass on the album besides his own songs. I now have to compete with two very good, aggressive writers. I know it’s influenced what I’m working on for the next album.

The album features contributions from a diverse array of musicians, including Deniz Tek and Tony Miller. What was it like collaborating with such talented artists, and how did their input shape the final sound of ‘Fire Printing?’

Deniz has been a regular contributor for a long time now. When I first met him in 1995, I passed him a copy of our first album, ‘Shambaholic.’ He called me up straight away and said that we needed to talk. I did some recording with him and Angie Pepper, then the Golden Breed album. I knew he was waiting for an invite to play on a Brain album. He came over for a session for one of his records. I handed him some lyrics I’d written and asked him to sing them. He got right into the VU thing we were doing. It was Deniz’s idea to start Career Records. We’d both been working with the Get Hip label. In 2002 or so, we had three albums and told Gregg we were ready to go. No reply. The Cynics had reformed, and he was focused on that. My idea was that The Brain and Deniz were the Career house band—like Booker T at Stax. I’m always happy to work with Deniz if he wants to bring a project here to record. I get to play on his records too. In 2017, I did a short East Coast tour with his band. I got drafted on short notice to play keys. He trusted that I could show up with only two weeks to learn the songs and one rehearsal and be able to cover 20 songs. Deniz called yesterday to ask for the audio for a cover of the Fleetwood Mac song ‘Oh Well.’ We’d done a session for Jack Rabid’s Big Take Over radio show. It’s going to be on a Mojo magazine Fleetwood Mac tribute CD. This is no small thing. My audio archives are well organized. It took me about two minutes to pull up the file and send it off to him.

I mentioned that I was salvaging some unused Ric Parnell drum parts. Deniz had an early experimental session with Ric that was never used. I told Deniz what I was doing. He asked me to send him stereo mixes of those drums. It took Deniz a bit to get his head around working this way—reverse engineering songs. I told him to chart out the songs and consider the sections as building blocks. He’s now got an album completed. I gave Deniz some unused Brain material too. I think these new songs are a strong collection. It’s made Deniz step out of his comfort zone. I can’t take much credit except for showing him the way.

Tony Miller was introduced to me by a mutual friend, Valis Hertel, a DJ from St. Louis. Tony is an extended member of the Elephant 6 crew. I wasn’t quite sure how to use him at first. Colter Langan had been working with us for a while but started to drift away when Bobby and I were doing ‘Fires Which Burnt Brightly.’ When it came time to start work on the follow-up, Colter came in one day and recorded three ideas. He never returned to finish them. I gave one of those tracks to Tony to try and write some words. He came right back with ‘It’s Alright With Me.’ In my own complicated producer’s role, I told him the first verse was too obvious and that the song should start with the second verse he had written. That gave the song a surreal bit of mystery. He was good with that. It was sort of the same for his work on ‘Mirror Pieces.’ I’d struggled with that track since 2017. I’d tried three different approaches to the melody and failed. Tony never heard my previous efforts, just the track with that title. I was surprised he kept the title and used it in the song. His work forced us to revisit the track. Joe added the nice 12-string guitars.

He’s promised a song for our next album. He’s got a serious day job and a family, so he doesn’t have a lot of time for music. A few years ago, he visited Bozeman to explore a job offer. I’d hoped he would take the job, but he declined. It’s very expensive to live here, and it would have moved him away from family. The Brain is happy to have him in our orbit.

Matt Piucci was meant to play on ‘Fire Printing.’ I’d given him ‘Echo Of Apology’ and told him to make some noise. Unfortunately for us, the Rain Parade activity has been demanding, and he just couldn’t make time. I’d like to think he’ll do something with us again in the future. He was insistent about being asked.

Peter Holsapple from the dB’s played on a song Bobby and I wrote, ‘Telegraphy Ave.’ He’s also suggested he’d like another song to work on. I’ve got one in mind. I’m just waiting for Kris to write some words, then we can talk. It’s exciting to have worked with so many musicians I grew up listening to. Having most of Help Yourself play with us was a dream come true. The time Dave Walker spent with us was good too. He’d gotten himself into a bad situation. Playing music helped him out. Sadly, his depression took over, and he fell away. He’s a hermit now, living in a ghost town. The Brain is a sort of magnet that draws in like-minded musicians. My life has always been like that. My wife and my friends are never surprised by who might fall into our circle. I enjoy putting together people who would not have met otherwise. When Ric and Deniz met and compared notes, they found they’d both worked with Wayne Kramer. So there is some connection.

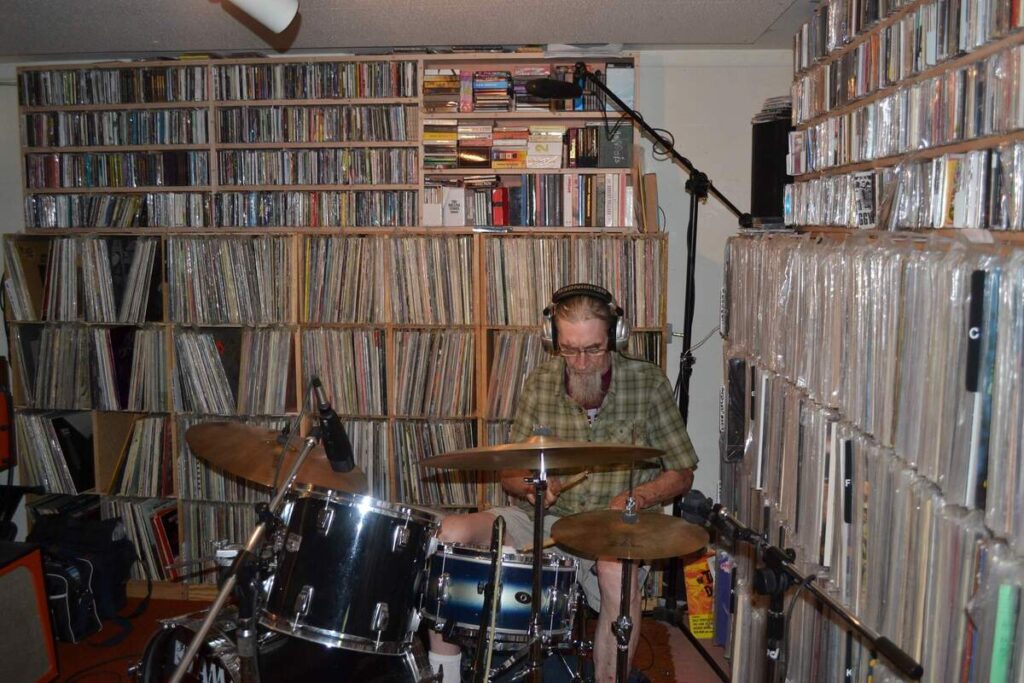

As the founder of Career Records and operator of God’s Little Ear Acre recording studio, you wear many hats in the music industry. How do these roles intersect with your work with Donovan’s Brain, and how do they influence your approach to producing and recording music?

As I’ve said, the studio came first. I realized right away that paying for studio time was not going to make things easy. I decided to spend that money building and expanding GLEA. It’s a modest but pro setup. Once I was running 8-track, I opened up to outside business. Those bands were lab rats. I could find out how things worked and how bands worked. Some were able to try ideas in the studio. I found that most of the local bands might have one exceptional song. I tried to make sure that one came out well. Some bands didn’t have the ability to think beyond what they’d rehearsed before they came in. Some bands didn’t even understand the recording process.

In 1994, I got the chance to produce an album for Man, the legendary Welsh group. I knew them well and suggested they fly out to Seattle to record. The studio time at Egg was cheap enough that the travel to the States was possible. That was my first experience recording on 16-track. Egg Studio had good engineers, so I knew I could manage. As soon as I returned to Bozeman, I bought a 16-track. This was the beginning of the endless Donovan’s Brain recording program, 30 years now. As a result, I lost interest in doing local bands. I’ll work with Deniz and a couple of other friends. In 2005, the studio expanded to a digital format. I had to rebuild and rewire the place. At the time, I was reluctant. My brother told me what I needed and that I’d never go back to tape. Working digitally has made it possible for the far-flung band to collaborate. The members are calling in from Australia, the UK, and all across the US.

I know what records sound like and what you can do beyond just recording a band. I would tell bands that anyone could record them, but if they came to GLEA, we were going to make a record. Most bands would record then have no idea what to do next. I quickly tired of trying to explain what they needed to do.

When we started Career Records, I had a good idea of how the industry worked. All those years in record shops were a good education. From my radio side, I knew getting a record played on the radio was a difficult task. We got lucky. When I started the label, a major distributor from Oregon approached me and said they’d take the label. This was huge. Twenty years ago, there were not all the options there are now with Bandcamp and such. I worked hard promoting our releases. Having Deniz on board opened a lot of doors. We got some good reviews in major mags. The big coup was Penny Ikinger’s album getting reviewed in Rolling Stone. The persistent work helped build the label name. Roy Loney was told he needed to release Drunkard In The Think Tank on Career. He’d been waiting 8 years for someone to fulfill a vague promise. The deal was we’d do another straight away. I got to do my job as Career A&R, producer, art director, and promoter. That was a full-time job for 2 years. I had to put the Brain on hold, which probably led to the demise of the band in 2007. Roy’s record did well. I think we were all disappointed there was never another Long Shots album. We all talked to him. He just didn’t feel like he had any songs. My pal Jerker Emanuelson has graciously released a couple of outtakes from the sessions on his Hit The Hay series.

I’m a traditionalist. I want drums to sound like real drums. Career Records is all about guitars. No synth-pop bands. That said, I know how to mess with things. I have no problem using drum loops or drum machines. Those are the tools you have available. I’m not one to record endless parts to sort out in the mix. In theory, I have unlimited tracks available. I suspect we never do more than 28 tracks total, and that includes stereo keyboards. Once we start a song, I’m set up in mix mode. Every extra part has to fit in what will be the final mix. I can hear where the song might go. Once we get all the ideas down, I then look to find where that bit adds to the song. If it doesn’t, it can be ducked out.

Richard Treece had a curious way of working. He didn’t want chord charts. He could listen and learn. He usually wanted to do three passes or maybe more. Then he’d tell me to sort it out. No other clues. There were some songs I just could not decipher. When I returned to them for the box set ‘Convolutions,’ I now had the computer to help me. Once I put up the tracks and listened line by line, I could hear his arrangement. It was spread across those tracks. He knew what he’d done on each pass, where he’d got what he wanted. You could hear him searching for notes between phrases. I had to go through and find the good bits and remove the chaff. These marvelous complex parts were then revealed. I wish he’d been around to hear them. It just took time and patience to mix those songs. ‘Bok The Beer Elf’ and ‘Brave New Girl’ are examples.

Early on, I told the band we were going to make records and they were going to get released. We weren’t just going to make a cassette and play bar gigs. I was already looking over the horizon. We are not a Bozeman band. That just happens to be where I live. It worked. We got some small deals and suddenly had releases in Sweden, Germany, and the US. When Career started, I just treated the label as a major player. Everything we did was meant to say we were confident, not a little indie label. That meant the album covers had to be world-class. Every release had to stand out on the shelf next to major label stuff. Art on the inside, art on the outside. I’ve been buying records for over 60 years. I learned to look for records that made you pick them up. If you can get them to do that, at least they know your name and hopefully buy it.

Even the label name was a calculated move. Deniz didn’t suggest any names for our new venture. I sat down and ran down a list of classic labels in my head: Chess, Checker, Command, Columbia, Cobra, Cadence… Career. Career Records has a double meaning too. I created the logo in the style of some old favorites too. It’s not a silly joke name or impossible to pronounce.

Looking back on the discography of Donovan’s Brain, what do you consider to be the standout moments or defining albums in the band’s journey thus far?

We’ve done 16 albums now. One of those was a 3-CD box set, or maybe 3 double albums. There is something to like on them all. I only have one regret, and that’s the mix I did for ‘Tiny Crustacean Light Show.’ It was our best seller on Get Hip, so there is no telling. I’ve remixed the album. It sounds better to me now. I haven’t done anything with it yet. I’ve moved on.

The other day I said, when asked, my favorites are:

‘Shambaholic.’ That’s when I was sure what Donovan’s Brain sounded like. I’d been recording for a couple of years. I realized there was a common thread tying some of the songs together. It’s about my frustration with my life in California and the breakup with a longtime girlfriend that precipitated my move to Montana. My last year in the Bay Area was a right royal mess. Then the first two years in Montana were not easy. We did play some of these songs live with Richard Treece. That was a thrill to hear them come to life on stage.

‘Great Leap Forward.’ It was just that. It was the distillation of two years’ work. The other songs from that period make up Tiny Crust. Great Leap was the real follow-up to ‘Shambaholic.’ It’s our psych sound, expanded with some very good players and songs. My ’60s West Coast influences show up on a few songs. That was the best work the local Bozeman band would do. I’d pick songs like ‘Following Orders’ and ‘Crystal Palace.’ Those are from Colter and Jeff Arntsen, respectively.

Beginning with parts of ‘Fires Which Burnt Brightly’ onwards, we’ve been on a solid roll. A very prolific time. I have to visualize the albums as the flood of songs poured out.

‘Heirloom Varieties’ is another one that I think is just about perfect. I’d choose the eleven-song album over the fourteen-song CD. Bobby came back exceptionally strong after his accident. Scott stepped up, as did Tom. It might be the one I’d suggest if someone wanted to know what we sound like.

It gets complicated after that. I reviewed my diary and found that there hasn’t been a gap in our studio work since 2017. The first 3 songs on our side of ‘Burnt Trees In The Snow’ are the starting point. Scott, Kris, and I each had an A-list song. Mine, ‘Gandy Dancer,’ is a particular favorite. It began as a very different song. Ric added his drums to that. What he did was so good I had to go back and write something better to match the quality of his playing. It’s another dream song. I was in a train station but could not get to the platform where my train was arriving. I just ran with the railroad theme. Gandy Dancers, the crews that laid the rails by hand, are a sort of romantic image. They had work songs, so they were hitting stuff and lifting stuff in unison. I write a lot of lyrics that are more about imagery rather than a linear story. A lot of modern music is confessional with lots of detail. I try to leave it up to the listener.

All that has come since 2017 is one continuous work in my mind. Despite that, the albums are all very different. Each has a unique feel. We are writing so fast, there are songs that don’t get used right away. I know I’ll find the right place for them eventually. It’s well thought out. Not random at all.

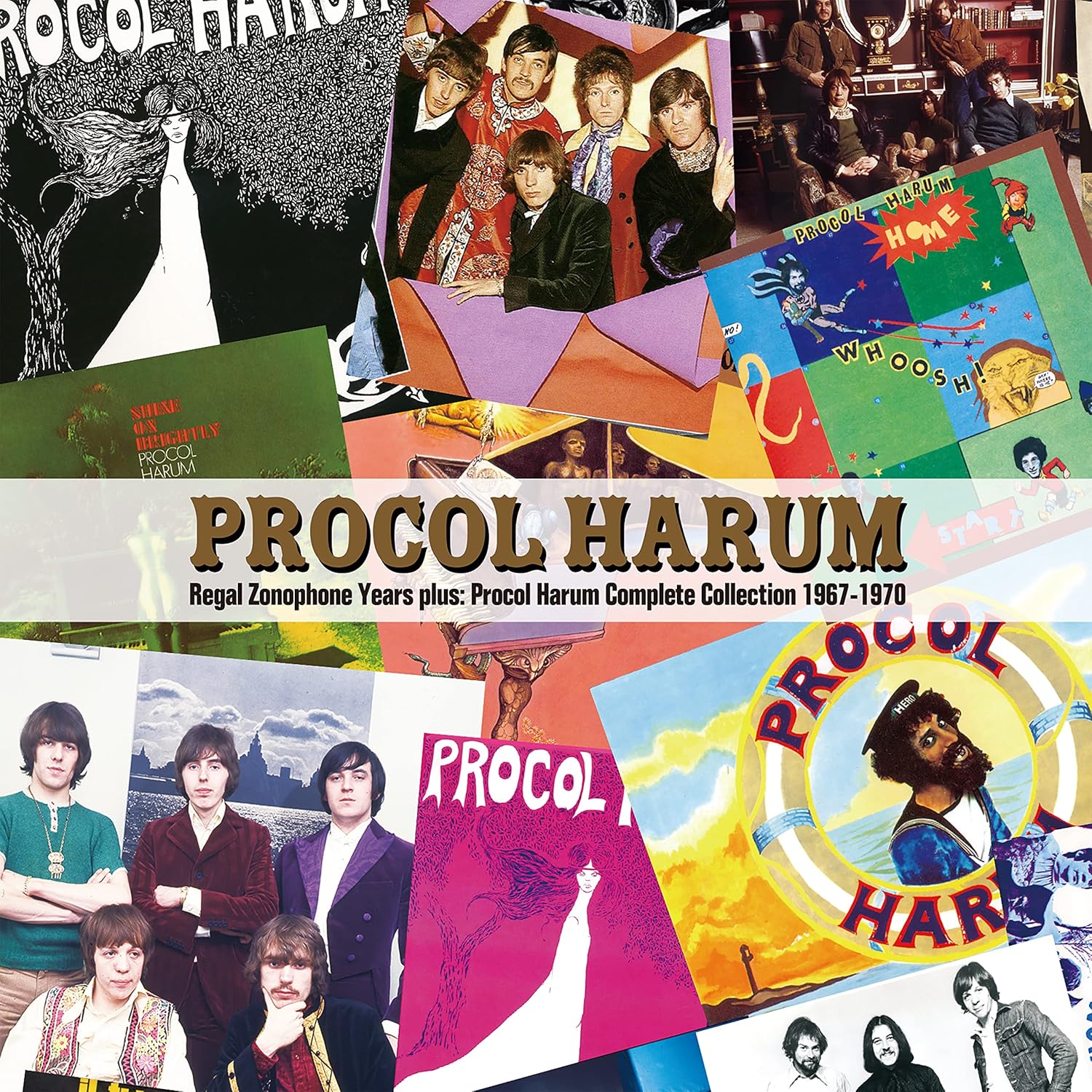

The double CD, ‘Sandbox Shadows,’ is the result of having so many songs. I decided it would be easier to put out two albums at once. They are two very different albums. ‘Sandbox Dispatches,’ the black album, is taken from my journal, telling about a very difficult period in my life. Two Suns, Two Shadows, the red album, is a collection of Brain songs without any concept. A couple of ‘Sandbox’ songs did leak over onto Two Suns. I was writing so fast at this point, I’d often start a song and then come up with another idea, so I was working on two new songs at the same time. Looking at the track lists now, I feel like there are no weak songs. Scott gave us three very good ones. I’m most pleased with ‘Changing Textures,’ ‘Failure To Achieve,’ and ‘The Inquisitor.’ Several of the songs were what I thought were obvious tributes to favorite artists. ‘The Inquisitor’ was an attempt to write a late-period Traffic sort of piece—Rhodes piano and synth. Absolutely no one noticed that ‘Secret Society’ was pure Procol Harum. Bobby Sutliff had sent over the demo for ‘Telegraph Ave.’ His original was heavy on the organ. I told my wife that would be great if we were Procol Harum. As soon as I said that, I stopped in my tracks and gave it some thought. The next morning I woke up with the first lines of lyrics, which I felt were pure Keith Reid. That’s Deniz Tek and Jim Dickson from Radio Birdman on that one. They knew exactly what I was after.

Work on ‘Faith In Failure’ started before ‘Sandbox’ was completed. I was waiting on Tom and Matt for some overdubs in 2020. There were those six songs we didn’t use for ‘Sandbox,’ but I decided to start fresh with songs written specifically for the next album. As a result, ‘Faith In Failure’ has a unified sound. A lot more keyboard textures. Bobby handed me two tracks he had written for his solo album but couldn’t find lyrics for. They came labeled ‘Jangle #1’ and ‘Jangle #2.’ The first one was a complete song with guitar solos. The second one was just a ninety-second demo. I had to work out an arrangement using those elements. That became the title track.

At the end of 2021, we were asked to submit some music for a film project. That’s a strange story, which I’ll tell another day. I am always recording instrumental things for my own pleasure. I’ve done some film music in the past, so I like to have a library to draw from. Scott had given me ‘Holding My Own.’ I told him that reminded me of a Pink Floyd soundtrack song. He agreed. I put that in the folder with ‘Connexion Complète,’ ‘Cultured Memory,’ and ‘Des Formes Qui Changent Lentement.’ ‘Cultured Memory’ is based on the ‘Faith In Failure’ chord changes. I liked them and thought I could do something completely different with them. That was done in the style of Neu! ‘Distance Is Created By Time’ and ‘I Don’t Dream Anymore’ were ‘Sandbox’ leftovers. I had to put a lot of work into those two to get them finished. In the end, the whole thing came together in just a few weeks. Ric’s work on these songs and a couple for ‘Faith’ were the last things he recorded. The results were well received. I didn’t know how people would respond to the synth instrumentals. Seven of the songs are just myself with Ric adding drums to a few.

Work on the second half of ‘Faith In Failure’ benefited from this slight diversion. Ric would never hear either of these two albums completed. Bobby had heard the soundtrack and the nearly finished ‘Faith In Failure’ but not the final track list and mix. The guitar solo he did for ‘I Would Not/Story In A Story’ was the very last thing he recorded.

The new one, ‘Fire Printing,’ holds a special place, as it’s the work of the new band. It was a fun one to do despite the lingering gloom. It also shows the range of what we can do. It’s a testament to Joe and Scott that it’s a strong, unified album. The new songs we have are showing a new direction. I had to break some habits while working on ‘Fire Printing.’ It really is a new band.

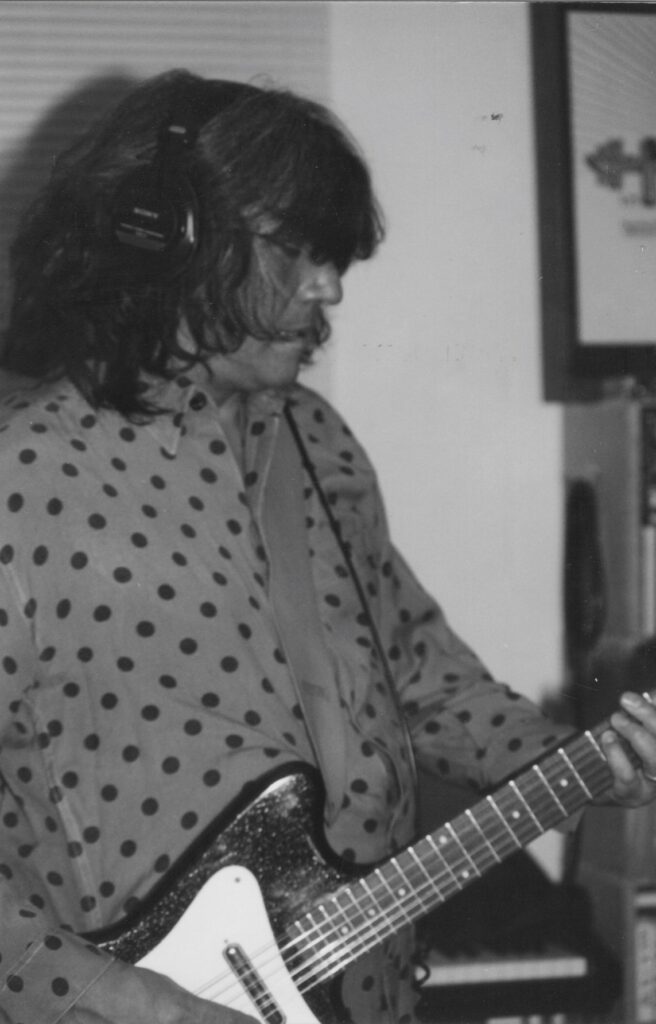

We are not a retro psych band that wears striped bell-bottoms and polka-dot shirts. We are not Dukes Of Stratosphere rewriting classic ’60s songs. If you listen closely, you might hear a bit of something old. It’s hidden away carefully, so it’s just a texture, not a tribute.

The Montana-based recording workshop that birthed Donovan’s Brain was a response to the DIY ethos of the ’80s music scene. How has this ethos shaped the band’s approach to creativity and collaboration over the years?

When I started playing guitar again, I was listening to Green Pajamas and bands like Bevis Frond. You could make your records at home and put them out yourself. There was a strong ‘zine scene that supported these efforts. I was in awe of what people were doing on very limited budgets and equipment. I was also a huge fan of Rain Parade and Windbreakers. Of course, REM were the ones who kicked open the doors. Guided By Voices finally got noticed too. All these bands were the antidote to the horrid MTV sounds that were all the rage. In the way punk was swallowed up by the industry that hated that music and spit back out as New Wave, with a skinny tie. The college rock scene got totally co-opted. I don’t want to point fingers, but there were some bands that were more than willing to sign on and play the game.

Donovan’s Brain was doing something totally foreign to what others were doing on the local scene here. It was only when I was able to meet some of the bands passing through and traveling around to see music that I found there was a place for us. I never thought we should try and sound like Olivia Tremor Control, though they were another band I looked up to. We did cover a Guided By Voices song early on. A couple of reviews have compared one of our songs to GbV.

The collaborations are a result of my efforts to meet musicians I like and simply asking if they could play some guitar. Most people are not precious about their talents and, when asked, are happy to join in on the fun. We make music because we have to. It’s what we do. A lot of the people who’ve passed through the band have had some degree of success. They’ve had major label deals and toured. At this point, it’s obvious that it’s a different time. What we do isn’t aimless. We work towards a goal. The albums get finished and released. It becomes real and escapes into the world. The fact that people seem to like what we do is all that we need to be encouraged to continue on and do it again. It’s self-sustaining now.

“Donovan’s Brain has always evolved musically”

‘Fire Printing’ is the first album to feature the revamped lineup. How does this iteration of Donovan’s Brain differ from previous incarnations, both musically and in terms of chemistry within the band?

There is a lot of excitement. It’s also the most involved lineup. Ric gave his time in the studio all his attention. After that, he’d go home and wait for the next session. Now it’s just the three of us who are making the decisions. It’s a different dynamic. I keep things moving, but I don’t try to drive things too hard. I think the interest will be maintained if we work at a comfortable pace. We can call the others in as needed. Starting work on the next album is the true test. I’m determined that it will be all new material with the three of us at the core. There are a couple of newer songs that Ric had played on. If we use them, we’ll either do new recordings or have Joe replace the drums.

Donovan’s Brain has always evolved musically, depending on who was contributing material. Obviously, we’ve lost Bobby’s distinctive style. Even though he hadn’t sung any songs on the last records, his playing was always there. The change has opened more room for Scott’s material. He’s been a strong voice the last ten years. I guess I’m the gatekeeper as to what songs we pursue. I’ve only passed on one of Scott’s, which I didn’t think would find a place on an album. He’s got plenty of other outlets, so he wasn’t offended. Joe’s first contributions fit right in. I think we share the same sensibilities. There isn’t a printed Donovan’s Style Sheet. Melody, guitars, and inventiveness are what I aspire to. I edit my own work. If it doesn’t come up to standards, it gets shelved.

The chemistry is different now, mostly because Joe is full of unstoppable energy. Scott McCaughey told me to expect this. Sutherland and Adragna connected in a way that didn’t happen with Scott and Bobby. There was a time when Bobby and I were a little competitive. He’d write a song, and I’d sit down and write one in response. It was friendly. We just pushed each other. With the current crew, it’s more of a controlled chemical reaction. Everyone tosses a bit into the cauldron. In the early days, people’s enthusiasm would spark and then fade. I couldn’t tell you what those people who got left behind think about it now. It just wasn’t their passion. As long as they didn’t make trouble, their contributions are appreciated. A couple of the guys did make trouble. I can’t completely erase them from our history. We just don’t talk about them.

The song ‘Hey Bobby!’ serves as a tribute to Bobby Sutliff. Can you share some memories or anecdotes about working with Bobby and the impact he had on Donovan’s Brain’s music?

I bumped into Bobby on an old online music forum. I introduced myself and let him know I was a long-time fan. We shared a lot of the same musical interests. While we were working on ‘A Defeat Of Echoes,’ there was a song that needed a guitar solo. I asked Bobby if he could do it. He said sure, as long as he could sing one line. I was happy to give him that; it wasn’t my song! The week Echoes was released, I flew out to Seattle to start work on the Roy Loney album Shake It Or Leave It. Bobby asked if he could play on it. He got his chance when one of the songs wasn’t working for Roy. Bobby said he’d try to solve the problem and did. Roy loved his contribution, and Bobby had a dream fulfilled. Two years later, when the Brain got back to work, Bobby asked me if he was a member of the band now. Of course. In the end, it was him and I who finished the album. The local band was no longer.

We had a deep friendship. He was going through some difficult times—a divorce and then that car crash. I tried to be there for him when he needed someone to talk to.

When he joined up, he gave me a dependable partner leading the band. He had plenty of real-world experience. We collaborated on the song High Street Hit Man early on. That effort was a good musical connection. Tim Lee was sort of envious that we could write together. He said he never wrote with Bobby. Bob brought in a song that had been meant for a Windbreakers reunion that never happened. I got to sing the Tim Lee part. My lack of musical theory would drive Bobby to distraction. He was furious I couldn’t tell him what key the song Secret Society was in. I couldn’t get him to understand that he just had to play a lick at the end of each line. The problem is I write a lot on piano, so songs aren’t in guitar keys that he would rather play.

He did give me a lot of support and compliments about my own songs and the mixes I’d do. He was a fantastic guitar player. It’s a shame he never met Deniz or Treece. I think they would have made a good team on stage. I was lucky to get to play with The Windbreakers in 2018. I didn’t dare get between Bobby and Tim. I worked out a part to add some color. I’d seen Bobby play at the benefit gig Rain Parade did for Bobby. Watching him and Matt go toe to toe was incredible.

When Bobby joined the band, I think the local boys realized we were serious and planning to take it to a different level. Maybe I made them feel like secondary members. I’m not sure. I just knew this was the direction I wanted to go. Bobby took his place in the band seriously. He helped transform us into the band we are today. I’ll never know what he would have done with us after finishing his solo album. That was such an important goal for him. His previous solo album On A Ladder had gotten one bad review. That hurt him deeply. Joining Donovan’s Brain meant his name wasn’t up top and the focus wasn’t all on him. Doing the solo album was difficult for Bobby. He was suffering from a partial writer’s block. We talked about that a lot. He couldn’t just make up something; it had to be a real emotion he was writing about.

The last time I saw him, we were sitting in his hotel room in Jackson. He wanted to show me the guitars he’d brought down for the Windbreakers gig. I picked up one of the Les Pauls he had and started strumming. I found a little idea and casually worked it out. When I hit the B minor chord, I said, “Damn, Flamin’ Groovies.” Bob looked at me and asked me if I’d just come up with that idea. I told him I had. He seemed a little stunned. I always figured we’d meet up here soon to record together. It was discussed but never materialized.

The album ‘Fire Printing’ was released just one year after ‘Faith In Failure.’ How did the relatively short gap between albums influence the songwriting and recording process for ‘Fire Printing?’

Well, that is the idea—to try to put out an album every year or 18 months. When I checked my notes, I saw that I’d started writing for ‘Fire Printing’ in the spring of 2022. ‘Faith In Failure’ was nearly done by the end of summer. I put work on hold as I was waiting for Jim Dickson to schedule a recording session to add some bass. There were some obstacles that made that impossible in the end. In the interim, I was writing. I had a twelve-song album by the beginning of 2023. It felt like it might be the last collection of new material. Scott and I discussed who we could bring in to play drums. I was about to audition a Montana drummer who had been asking for a chance.

When Joe came on, it was like a shot out of a cannon. Nothing changed. Joe had some strong ideas, which I liked. His method of recording drums is different from mine. He got good results, so I couldn’t question it. There was also the EP we put out in February. There were songs that Joe and Scott had offered up, which were a little more punky than the album tracks. I wrote a song in the same noisy style to give us three songs. Joe had done the drums, then decided to redo them. I asked him for the original tracks too. He had to admit he didn’t save them. I explained why I wanted the first pass, so he did another in the same wild style. I edited the two parts together. He liked that idea. That was me being influenced by his own methods and ideas.

I wanted to show Joe how we work, so I was determined to get ‘Fire Printing’ out in 2024. I’d scheduled a release in August. I didn’t know how long it would take to finish the mixes and do the cover. It came together very quickly. I had someone in mind to do some artwork for the cover. I was preparing a mock-up when I stumbled on the image that I ended up using. There was a miscommunication with my usual pressing plant. I turned to another firm I’d worked with. Their turnaround time was very short. I couldn’t see any reason to delay the release, so I just did it. Four releases, five albums in three years. Maybe asking too much of the fans and press. My philosophy is to get the music out. The fan will eventually catch up with us. That’s proved to be the case. People are buying our old releases. People buy one album, then come back and buy more. I have to consider my own mortality too. I’ll be 72 years old this summer. I’d like to think I have many more good years left, but I can’t ignore that my contemporaries are leaving us at an alarming rate. The next album will be out in the fall of 2025. That gives us plenty of time to build up a good collection of songs. It also gives me a rest from the business side. Besides Faith In Failure, Career released the Bobby Sutliff album and the Sand Pebbles. That was the busiest year we’ve had for a long while. I was reminded how much time it takes to do that. It’s about that time I wished there was a label manager to do some of the work.

Beyond the music itself, Donovan’s Brain has built a community of collaborators and friends over the years. How has this network of musicians influenced the band’s evolution and creative output?

It’s part of the grand plan. Sometimes it’s just a matter of circumstance. John Goodsall happened to come out to Montana to visit, and Ric wisely brought him by. John is another session pro. I showed him the choice of guitars and played him the songs. A couple of passes on each, and he was done. I do like the idea of a different point of view added to the songs. It’s funny. When I wrote ‘Hey Bobby!’ I figured I’d do it in the style of Scott McCaughey. He got back to me and said he did it in the Beatles style, and was that okay?

Right from the start, with Richard Treece and Ken Whaley helping finish ‘Eclipse And Debris,’ we were lifted out of our local band status. Then we got Dave Walker. He’s a guy who played in a couple of very famous bands. He claimed he wasn’t much of a songwriter, but then jumped right in. Co-writing with him is no small feat. As I said, I think the local guys realized they were not in the same league. The revised band didn’t have that concern. If I’m going to reach out to someone, their work is going to be heard.

What’s next for Donovan’s Brain? Are there any upcoming projects or collaborations on the horizon that you’re particularly excited about?

First and foremost, a new album. I hope the songwriting on this one is split evenly between the three of us, and then whatever else appears. There is always an archive project brewing. Some songs have been around for ages. They get put on the initial short list, then get pushed off by new songs. The digital EPs would be part of that idea too.

We’ve discussed trying to do some live shows. The logistics are an issue. We’d need at least five people on stage, preferably six. That format worked for Terrastock. Two keyboards for some songs are necessary. At least we can talk about it. I’d just like to get Joe and Scott here to do some recording. Johnny Sangster has suggested we come out to his studio in Seattle. That might be nice.

I’m always working on the Armchair Explorers krautrock thing. The soundtrack got a couple of those songs. There are some recordings from ages ago with Jeff Arntsen and Jonathan Drews from Eyelids. We recorded two long pieces, which I’ve been trying to make sense of for years.

As far as collaborations, well, that just depends on what comes up. I do have a song I want Peter Holsapple to help me with. It’s an unfinished Bobby Sutliff song. Beyond that, I feel like the next album will be the core band. We are capable of doing it all ourselves. I’d like to see how we manage. The new songs aren’t far enough along to start making plans.

Let’s end this interview with some of your favorite albums. Have you found something new lately you would like to recommend to our readers?

Favorite albums? Beach Boys – ‘Today!,’ ‘Who Sell Out,’ ‘Rubber Soul,’ Guided By Voices – ‘Bee Thousand,’ Miles Davis – ‘In A Silent Way,’ Sand Pebbles – ‘Eastern Terrace,’ Albert King – ‘Born Under A Bad Sign.’ That’s just off the top of my head. I’m always adding new music to my collection. New bands. I’ve been digging Silver Sound, Andrew Tanner’s Sand Pebbles side band. I quite like the new Granddaddy. Jason Lytle is a friend and another Brain collaborator. The Beths. I was told to check them out. The album is great, if not a little familiar. My pal Michael Slawter has quietly been putting out some great power pop records. And let’s not forget Joe’s band Junior League. He’s got a new one in the works.

I do listen to a lot of new, popular music. I can’t say I connect with it. I just want to know what’s going on and what is considered new, important music. Then I turn back and buy old jazz and blues records.

Thank you. The last word is yours.

The country that rules magnetism, rules the world.

Klemen Breznikar

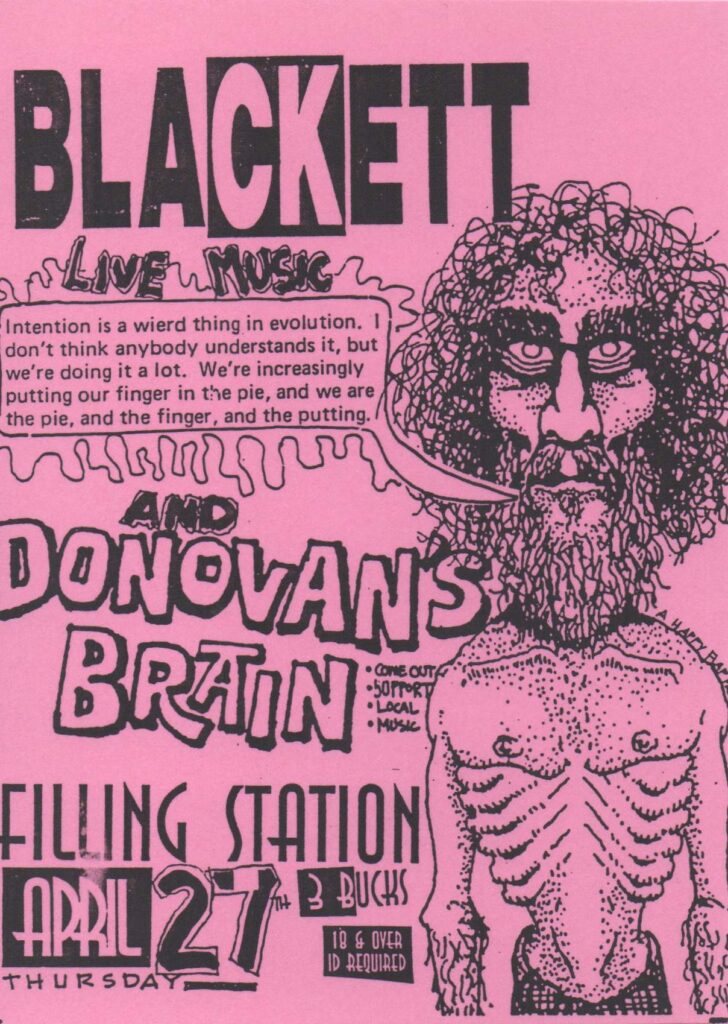

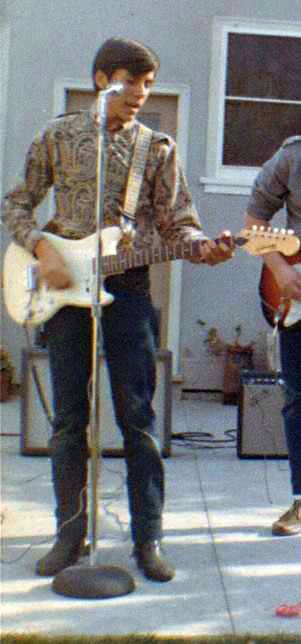

Headline photo: Donovan’s Brain at Filling Station (April 27 1996)

Donovan’s Brain Official Website / Facebook / Bandcamp

Career Records Official Website

Radio Birdman | Interview | Deniz Tek | New Album, ‘Long Before Day’