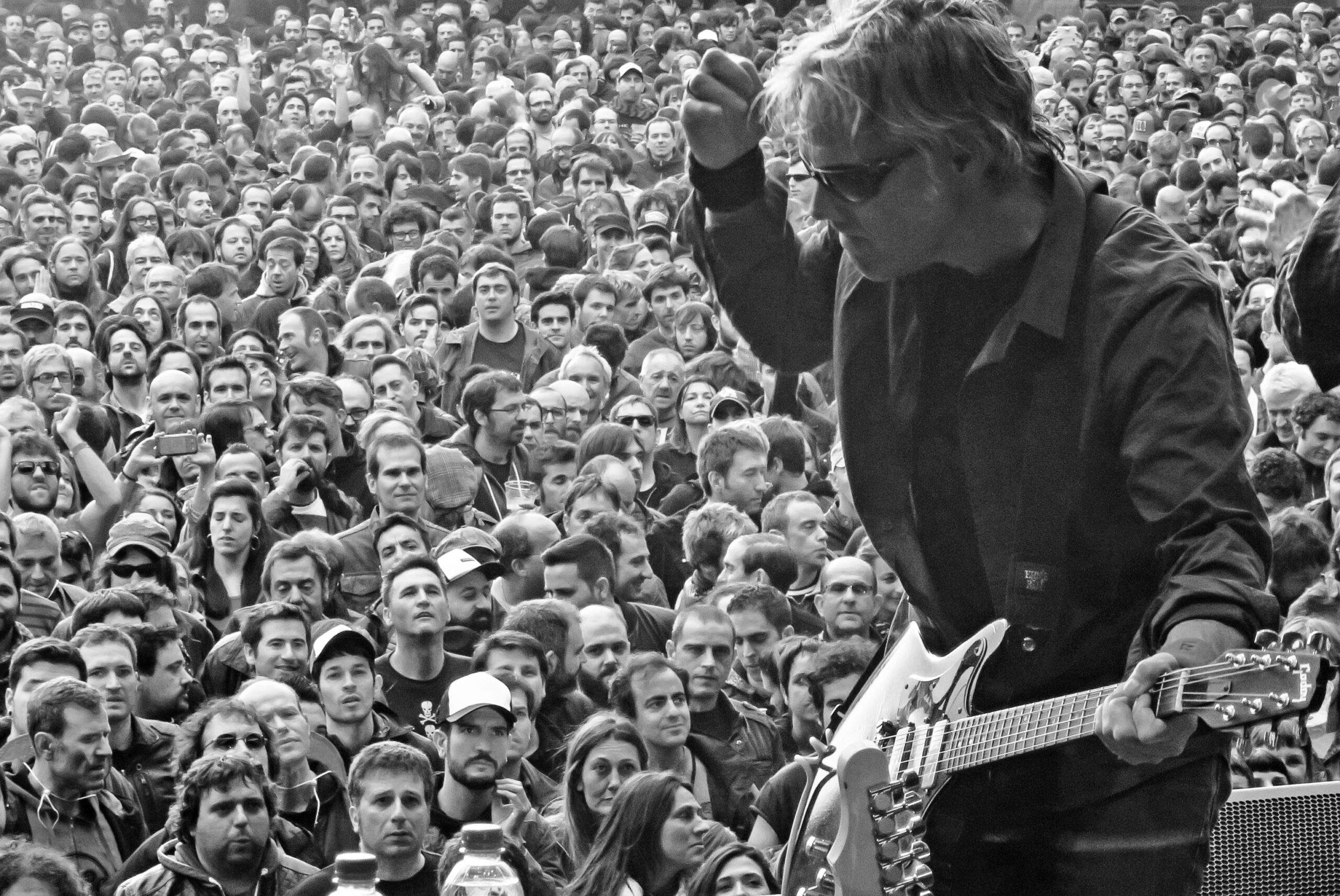

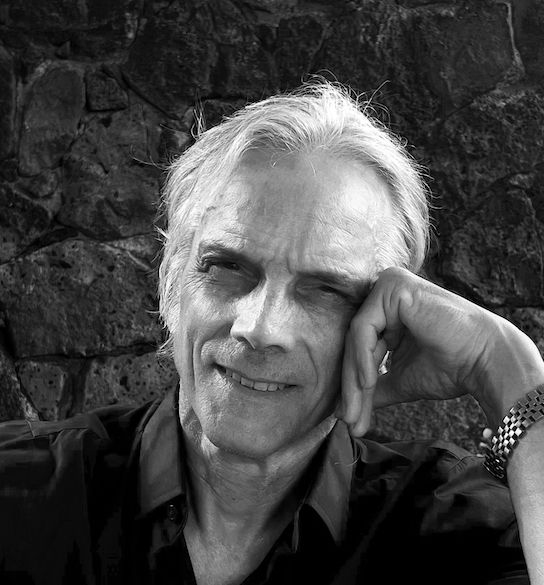

Radio Birdman | Interview | Deniz Tek | New Album, ‘Long Before Day’

Deniz Tek is a guitarist, singer/songwriter and record producer from Ann Arbor, Michigan, most well known for his work with Radio Birdman. He has a fantastic new solo album, ‘Long Before Day,’ out via Wild Honey Records.

The new album features Tek’s vocals and signature guitar playing, complemented and interlaced with the guitar work of Anne Tek. The hard driving rhythm engine of veteran Bob Brown on bass and Keith Streng (from The Fleshtones) on drums provide a rock steady foundation, with “roll” included. Recorded on tape, ‘Long Before Day’ evokes vintage sonic values. Old-school recording techniques bring spontaneity and a genuine live feel to the sessions.

“A guy who likes to play the guitar”

Roy Phillips: Obviously most well known guitar players have their own style being a major part of their appeal, but it’s also equally a “sound.” Where did your initial sound come from Deniz?

Deniz Tek: It’s interesting that you differentiate “sound” from “style.” There is a difference, but the longer you play the instrument the more style begins to inform sound and the line between the two concepts becomes blurred. Sometimes it works the other way around, and sound can influence style, like a painter working in varying media. As a very experienced eye can recognize Monet by a single brush stroke, we can sometimes hear the unique signature of Keith Richards or Jimi Hendrix in just one note or chord.

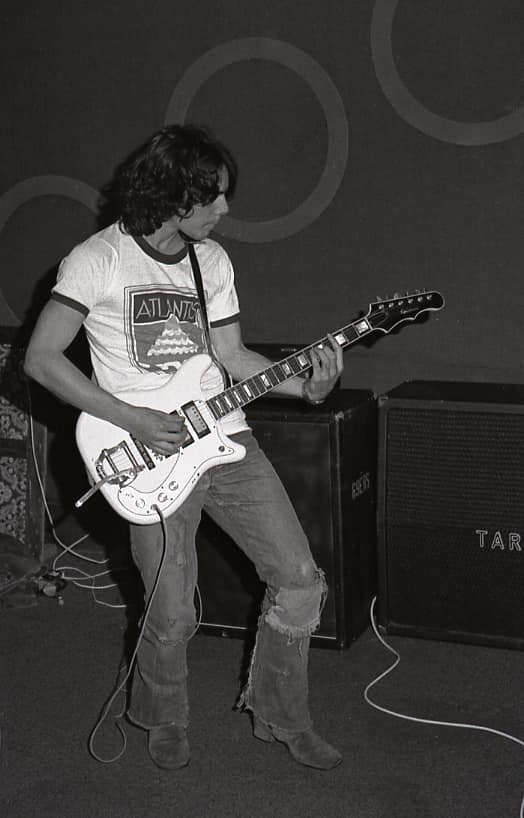

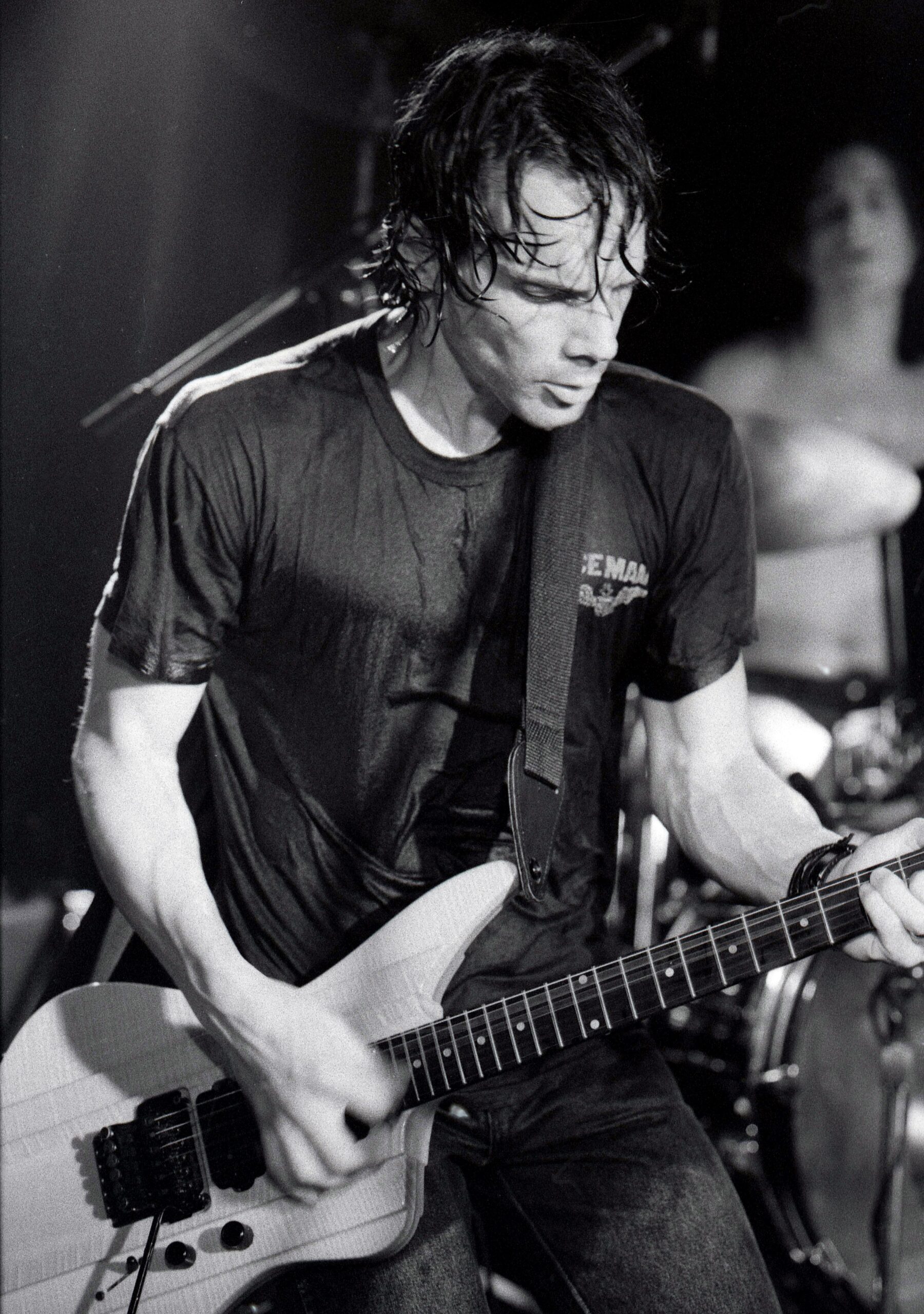

My initial sound would have been what you would expect of a twelve year old banging away on a cheap acoustic guitar. I got a Harmony Bobcat and a small Gibson amplifier with a 10 inch Jensen speaker for my thirteenth birthday, and my sound became electric – clean and bright. Since then it has been an evolution. In the early days the sound was dictated by what I could afford and the equipment that I was able to get my hands on. Later on, when I had the resources, I could begin to develop a sonic palette that would allow me to get closer to my musical vision.

My guitar sound on Radio Birdman’s first album came from a 60’s vintage Epiphone Crestwood guitar through an Australian solid state Phoenix amplifier, with an MXR Dyna-Comp and Cry Baby wah for solos. I moved on from that stuff a long time ago but I don’t think I’ve ever actually sounded better.

Roy Phillips: Your first time in Australia was around the early 70s and a really great period for Rock music. What Australian bands from that era were some of your favourites and how did they influence your own music?

My first time in Australia was in 1967 and there were many great bands. Some of my favourites were the Masters Apprentices, The Loved Ones, The Purple Hearts, Zoot, The Missing Links, Phil Jones & The Unknown Blues. And of course The Easybeats. I loved hearing those bands’ hits on the radio. When a record resonates with you, it spontaneously becomes part of you, and can come out later in unexpected ways.

In 1968 I returned to Ann Arbor, to find that everything had changed. I had missed the Summer of Love. Music power there was peaking. We had many great bands and in the summer, free concerts every weekend.

In 1972 I returned to live in Sydney. By then, the great sixties bands were mostly gone. Replacing them was an electric boogie/blues stoner scene, with Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs, The Coloured Balls, The La De Das, et cetera, and also some “progressive” rock bands. I didn’t like any of it. I found it dull, boring, and a waste of time and energy. Perhaps the one exception was Daddy Cool. Fortunately, there was some good stuff coming in from overseas. In the early 70’s I recall seeing Muddy Waters, Furry Lewis, Frank Zappa, Lou Reed, The Rolling Stones.

Regarding records of the early 70’s, I was listening to The Stooges, who were still making great records; The New York Dolls, Alice Cooper, and the early Blue Öyster Cult albums. I was also interested in Captain Beefheart, and Lou Reed’s solo work, among many other things. From the UK , I was listening to Syd Barrett era Pink Floyd, T. Rex, David Bowie, The Kinks, The Who, The Stones, Pink Fairies, and so on. After I became friends with Rob Younger, we would spend many nights-up listening to his great collection of 50’s and 60’s pop singles.

“Music in general plays a much smaller role in people’s lives now”

Roy Phillips: While everyone has a personal relationship with music, its effects on the culture around us may not be immediately apparent. Do you think it can still inspire change on such a large scale as Elvis Presley, Bob Dylan, The Beatles or David Bowie? Or have we simply run out of ideas due to AI being the major part of creativeness in the arts in general?

AI recycles and recombines things that already exist. It can come up with new music on demand that emulates a certain style, has universal access to data to work with, but (so far) it does nothing truly original. AI plays to target audiences’ preconceptions and biases, reinforcing them, and this tends to insulate people from hearing new things. At the same time the profit motive prevents AI from developing in new and unexpected ways. Welcome to the club!

Music in general plays a much smaller role in people’s lives now. 50 or 60 years ago music meant so much to young people. That is gone. There is a plethora of sensory input of all kinds available for young people now, and music can only occupy a small fraction of the bandwidth. The reduced attention span and the need to click on the next thing several times in the space of a minute has reduced a lot of young people’s music experience to checking out ten second Tik Tok clips. Those factors have made it much less likely that a new music trend could have a large cultural impact these days.

Roy Phillips: Garage rock which is really a 1950s thing, one thinks Buddy Holly, Gene Vincent, Elvis Presley, Scotty and Bill as real true garage punk bands but it also did really well in the 60s and 70s too and yourself being a part of that with Radio Birdman / Visitors. What are some of your favourite records from those days and why?

I don’t see “garage punk bands” in quite the same way that you do. My idea of a garage punk band is a bunch of guys who are just beginning to play and not technically proficient, but they have a ton of energy and enthusiasm, and they come up with simple songs that are charming. These kinds of bands started in America in the mid sixties as a response to The Beatles. After we saw the Beatles on TV, every kid wanted to play guitar or drums and be in a band. My first band was like that. We were thirteen, school mates, and played in my parent’s basement. In Michigan in the winter it was too cold to play out in the garage.

Some of the garage punk records I liked at that time were The Trashmen’s ‘Surfin’ Bird,’ The Kingsmen’s ‘Louie Louie,’ The Shadows of Knight ‘Gloria,’ Blues Magoos ‘(We Ain’t Got) Nothin’ Yet’. After Lenny Kaye’s ‘Nuggets’ collections and Greg Shaw’s ‘Pebbles’ we had access to a lot more rare garage punk records that I didn’t know existed. Nuggets and Pebbles were many people’s gateway to garage punk treasure.

Scotty Moore, Bill Black, Buddy Holly – those guys were not novices. They were masters of the craft. Radio Birdman wasn’t on their level, but we were a little bit beyond the garage. We had a classically trained pianist, for one thing. Chris Masuak was (and is) a technically brilliant guitarist. Ron Keeley’s drumming is nuanced and jazz influenced … getting my drift here? Anyway, we never saw ourselves as either garage or punk. I know others did.

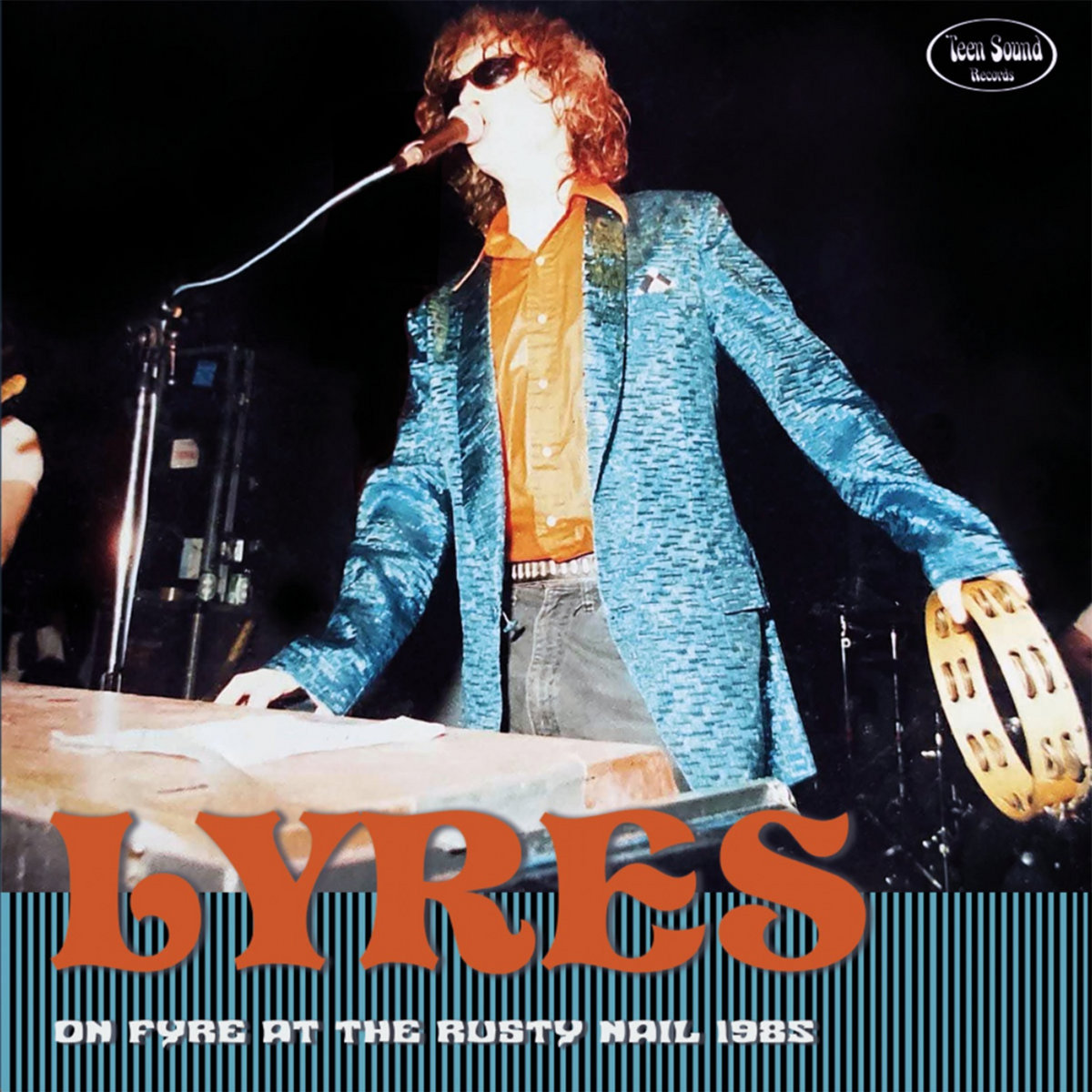

Klemen Breznikar: You are just releasing your brand new solo album, ‘Long Before Day’, are you excited about it?

Sure. It’s always fun to get a new record out. This one even more than usual because the end result is very close to how I wanted it to be. No regrets or disappointments. Of course, I’m not listening to it any more. After the mixing and mastering process, I’ve heard it enough times already. I’ll hear it again in five or ten years time and think “Wow! That sounds great – you mean we really did that?”

Klemen Breznikar: Do you feel that the pandemic had any impact on how the album ended sounding?

Yes. James Williamson and I had just finished recording and mixing the ‘Two To One’ album for Cleopatra Records when the pandemic hit. Then we couldn’t tour, so that allowed plenty of free time to work on my next album, which was ‘Long Before Day’. The starting point was some songs I had written for ‘Two To One,’ which weren’t used. I had a couple of years to write more, and then work and rework them. My wife Anne and I spent a lot of time playing the songs together, trying them out in different ways, and figuring out what worked and what didn’t. Normally I don’t have the luxury of so much time. The album certainly sounded better as a result.

Klemen Breznikar: Have you found the isolation creatively challenging or freeing?

That is a great question. The isolation provided ample space for the creative process to work, with a minimum of distractions. However, there was also a lack of new live input. For me, songwriting doesn’t happen in a vacuum. External experiences are raw materials for the process, and the more varied and interesting the better. So, being isolated is both freeing and challenging in some ways. One advantage of old age is that you have a lot of material in the rear view mirror to draw on.

Klemen Breznikar: The new album features the guitar work of Anne Tek, Bob Brown (bass) and Keith Streng (from The Fleshtones) (drums). What was the energy in the studio?

We recorded at Bob Brown’s studio in Billings, Montana. It was the first time we traveled off our island since the pandemic started. It felt great to get out again, and the energy level was very high. We were very well prepared, so there was no stress involved. It went smooth and quick. We recorded guitar and drums live, and in some cases the guide vocal was good enough to keep so some of the final vocals are live too. Bob was engineering the sessions. He had to push the “record” button, so his bass parts, and some extra guitar parts and most of the vocals were added later. Recording the basic tracks took two days, and another two days to finish the extra guitars and vocals, so four recording days in all. Everyone was enthusiastic. We worked hard, and had a lot of fun.

Klemen Breznikar: It’s fantastic to hear that you decided to record on tape, I guess you prefer the analog process?

I started out in the 70’s recording to tape, and I’m very comfortable with it. With modern digital recording you have an unlimited number of tracks and editing is very fast and easy. There is a tendency to throw an excess of material into the box, and you only end up keeping a fraction of it. You cut and paste the best bits together and the result may be technically more perfect, but loses spontaneity. Having a limited number of tracks and very few editing options means that you have to be ready to get it right as it’s being recorded. It’s much more live, and that comes across on the record. It sounds more real, because it actually IS more real. This was made possible because Bob Brown found an old Tascam half-inch 8 track tape recorder a few years ago. He got it restored and in good working order with some difficulty – there’s not many guys left on the planet who know how to fix them. I was over the moon happy, and my ‘Fast Freight’ album was the first thing he recorded with it.

Klemen Breznikar: I hope you don’t mind if we travel back to the 60s when you were just a teenager? What did your room look like? What kind of records did you own? What gigs did you see?

In my early teens, I shared a room with my younger brother. That room had African animal scenes painted on all four walls. Quite spectacular, really! I didn’t get my own room until I was 15. I had a couple of Rolling Stones posters, one of Mick Jagger playing bongos in the studio, from the movie “1+1”. I moved out at 17, and shared rooms with pals. I never stayed in one place long enough to do any decorating.

I started buying records at about age 11. My first single was The Beach Boys ‘Shut Down’ / ‘Surfin USA’. I had many of the surf and garage records of the day, plus the British invasion bands. ‘All Day and All Of The Night’ by The Kinks. All the Stones and Who hits. I also had some Motown records. The first full length album I owned was ‘Meet The Beatles’. In my later teens I got into the Velvet Underground, The Doors, CCR, and I started buying old blues records – John Lee Hooker, Lightning Hopkins, Mississippi John Hurt. I discovered Gary Davis and Blind Blake by listening to the first Hot Tuna album, which I loved and still own.

I was born and raised in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Being a culturally oriented university town, and very close to Detroit, there was a very lively music scene. The first live electric rock and roll band I saw was The Rationals, who played at my school. Some of the more memorable local gigs I saw as a teenager included The Stooges, The MC5, The Up, The Frost, The Amboy Dukes, Alice Cooper. Occasionally I saw touring bands from elsewhere: Johnny Winter, Pink Floyd, Ike and Tina Turner, The Band.

The week after my 17th birthday in 1969 I saw The Rolling Stones in Detroit, and that was life changing for me.

Klemen Breznikar: Was there a certain moment in time when you knew you wanted to become a musician for the rest of your life?

If there was such a moment, I can’t recall it. For as long as I can remember, I thought of myself not as “a musician,” but just as “a guy who likes to play the guitar.”

Klemen Breznikar: How did you meet Rob Younger back in the early 70s?

In 1972 I was living in a student house in Sydney. One of the students was Ron Keeley, who later became Radio Birdman’s drummer. I was in a band called TV Jones, and Ron was in a band called The Rats. The Rat’s singer was Rob. Ron brought him over to the house. He had on a crushed velvet suit, that hair, and a huge crucifix. I thought he looked like Rick Wakeman. We met, and he immediately noticed the record collection, and we started talking. We found that we had common interests, and we became friends. A couple of years later Rob and I were sharing a tiny house together. The Rats had broken up, and I had been sacked from TV Jones. That was when we got the idea of starting our own band.

Klemen Breznikar: What was the scene like in Sydney when you arrived? Australia had some incredible hard rock bands like Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs, Buffalo, et cetera.

After the Ann Arbor / Detroit scene of the late 60’s, and having seen The Pink Fairies at the Marquee in London, it seemed very tame. Heavy mid- tempo white boy electric blues at extreme volume, or bands doing prog rock that was already dated by the time they did it. I saw Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs, The La De Da’s (with Kevin Borich the guitar hero), Company Caine, Coloured Balls, et cetera. I never saw Buffalo. I did like Daddy Cool. At least they had a sense of humour and wrote catchy songs like ‘Eagle Rock’ … As I mentioned earlier, there had been a really exciting rock and roll scene in Australia in the sixties, but by the early seventies it was at a low point. The same thing was going on around the world – the unfortunate “country rock” scene coming out of California, the overblown British rock bands like Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple, and the deadly boring prog rock of bands like Yes. Even Pink Floyd, which had been a creative force earlier, came out with ‘Dark Side of the Moon’ which was quite ordinary and deeply disappointing. This all set the stage for something exciting to happen, and by the mid 70’s, sure enough, it was gathering steam. We were inspired by early 70’s bands from New York like The Dolls, Suicide, The Dictators, and the early Blue Öyster Cult, and when The Ramones and The Dead Boys came along it was a real breath of fresh air. In Australia, it was just us at first, and then The Saints.

Klemen Breznikar: Would you like to talk about your early band, TV Jones?

TV Jones existed from 1972-74. “TV Jones” was short for Tek, Vanderwerf and Jones. We went through a couple of band names before we were TV Jones, including “The Screaming White Hot Razor Blades” and “Cunning Stunt”. TV Jones was a better name. I was only just starting to write original songs then. We were doing mostly covers. Our set would typically contain songs by The Stooges, Velvet Underground, J Geils Band, Stones, Beefheart, Alice Cooper, and some older Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley and Elvis songs. I was the lead vocalist and played guitar and harmonica. We would wear heavy makeup, Warhol-inspired clothes, and we would do our own brand of “performance art” which mostly amounted to destroying things on stage and interacting intimately with the crowd. We managed to get a following in Wollongong – a smaller industrial city south of Sydney, but when we tried to work in Sydney it didn’t go as well. We were loved by a few fans, but were ejected from venues and most audiences were not ready for us. The other members decided it was time to “go commercial” and they didn’t see me as being capable of that, and they sacked me. They were right, of course!

Klemen Breznikar: How did you get in touch with keyboard player Philip “Pip” Hoyle, drummer Ron Keeley and bassist Carl Rorke?

I met Pip at the university. He was on TV Jones very briefly. He had no rock and roll background, and wouldn’t play straight 4/4 time. I loved what he did, but the others couldn’t get into it. He lasted only one or two gigs with TV Jones, but I called him immediately when we were forming Radio Birdman. I knew Pip would be incredible – a secret weapon. Ron, of course I knew from the student house, and both he and Carl had been with Rob in The Rats. Warwick Gilbert, who eventually took Carl’s place in the band, had been in The Rats also, but on lead guitar.

Klemen Breznikar: You just got to love how you got your name, … after misheard lyrics from ‘1970’, a song by the Stooges…

Ron Asheton told me that the original lyric as written was “radio buzzin’ up above”. When you listen to the ‘Fun House’ outtakes, sometimes it changes, but the final version is probably “radio burnin”. Radio Birdman is one way to hear it, and we all liked the name because it sounded good but didn’t mean anything.

Klemen Breznikar: Can you elaborate on the formation and early gigs by Radio Birdman?

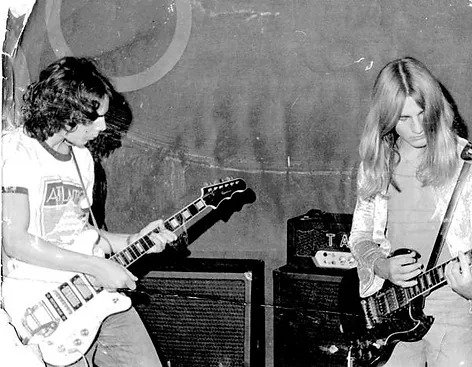

We got together as a quintet, one guitar and one keyboard, and rehearsed at a place called “Studio 20” in Darlinghurst. It’s still there – a moldy little dump with concrete walls, but you could be loud and it was cheap enough for us to afford. Our first gig was in September of 1974 at the Excelsior Hotel. We played and got banned from almost every inner city venue in Sydney, and when we couldn’t play anywhere, we put on our own gigs in garages and rented community halls for about a year. Then by sheer luck and with the help of Lou Reed, we got a residency at the Oxford Tavern, which allowed a bit of a scene to develop around the band. Pip left temporarily, and was replaced by guitarist Chris Masuak … When the pub was sold, we stepped in to manage the venue, and changed the name to the Funhouse. The inmates had taken over the asylum. We started booking bands that had been rejected for the wrong reasons, like us.

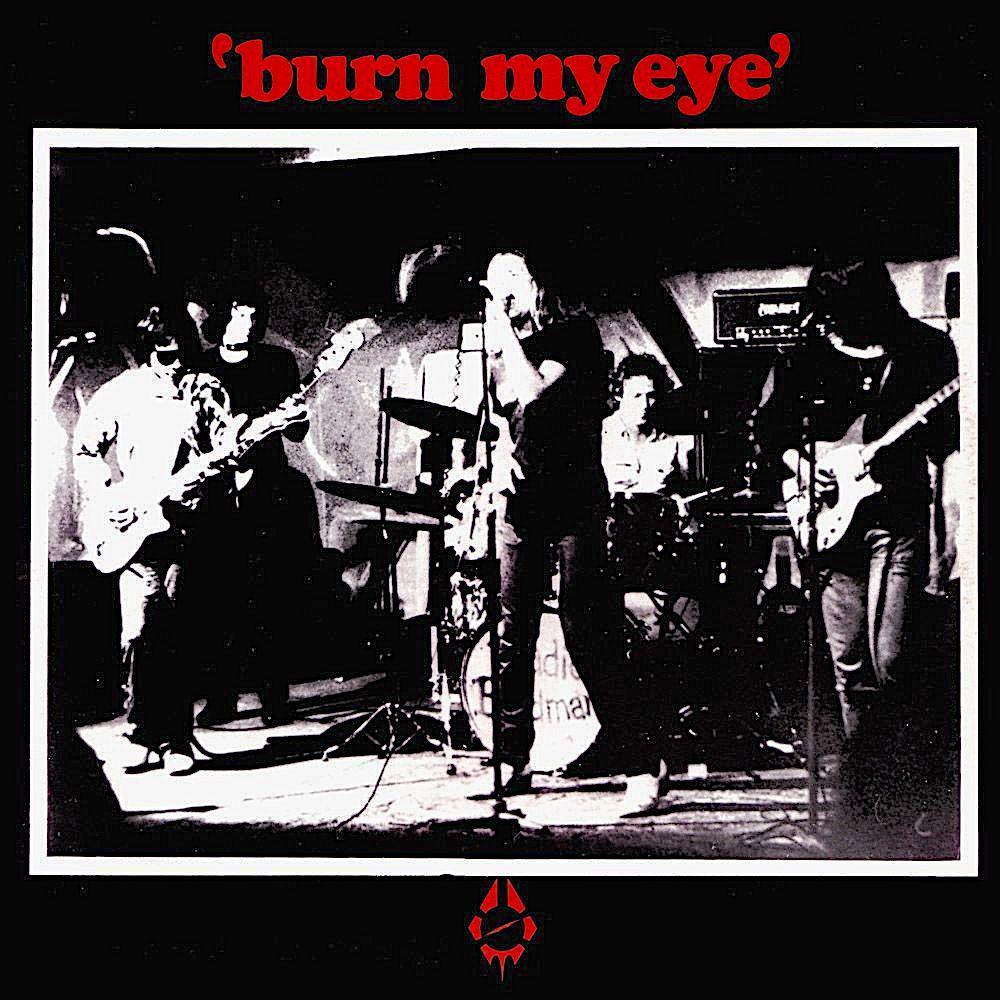

Klemen Breznikar: What were the circumstances around Rock Australia Magazine editor, Anthony O’Grady and the release of your first EP, ‘Burn My Eye’?

Anthony was a strong supporter and helped us a lot. He was something of a visionary – he saw where music was going, a little bit ahead of the times. He introduced us to some studios. Most didn’t want to work with us. The last resort was Trafalgar. We didn’t expect anything but Charles Fisher, the studio boss and producer, saw something in us that he liked and invited us to record some demos. These early recordings led to the first ep. Trafalgar formed a label specifically to release our records independent of the majors. It was the first indie label in Australia.

I remained friends with Anthony and spent quite a bit of time with him recently, just before he passed away.

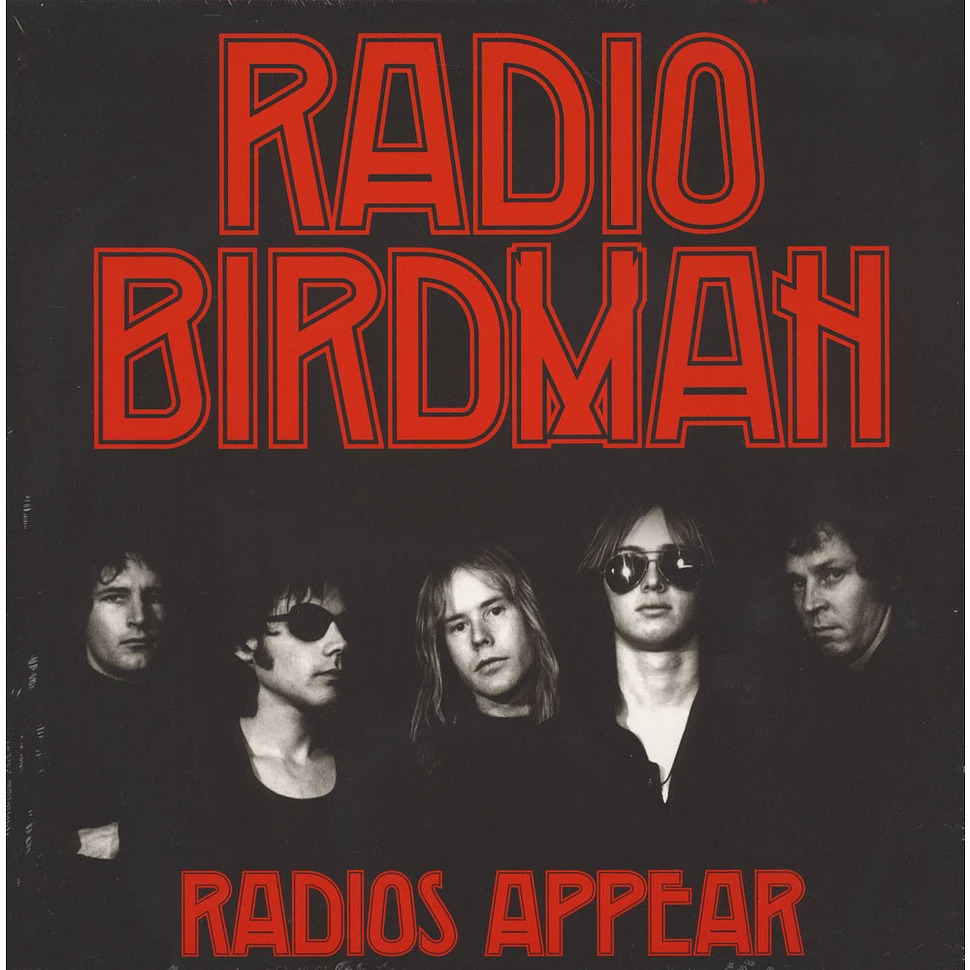

Klemen Breznikar: What led to the recording of your debut album, ‘Radios Appear’? What are some of the strongest memories from recording it?

Charles Fisher was keen to produce an LP after the ‘Burn My Eye’ EP was successful. It took several months to record because we could only work on it occasionally, when the studio was free – when they had no paying clients. We would sometimes go in, set up, record all afternoon, then load out and go play a gig that night. The studio was modern for its time, and it was very quiet – full soundproofing, carpets everywhere. We found big sheets of old rusty corrugated iron at building sites where sheds had been demolished. We brought them in our van, dragged them into the studio, set them up around the room to give the sound a bit of a harder edge. This million dollar sonically designed room, and the engineer John Sayers was appalled. But it worked. We recorded at stage volume, to get our sound, and so there was always spillover. We would try anything, like smashing empty beer cans on our heads in front of expensive Neumann U-47 microphones, for percussion. Weird stuff like that. We had a great time in that studio, and the fun element found its way into the recording.

Klemen Breznikar: Would you like to describe the underground scene at the Funhouse?

It cost $1 to get in, and the money all went towards printing handbills and posters and to pay the door girl. In its heyday, there would be 200 people crammed in, dancing and going wild. We would play a couple of sets. The first set would be loud, tight and fast. Then we would be smoking joints and drinking out of a bottle of Jim Beam in the toilets in between sets. In the interest of progress, we would always try something experimental in the second set so the regulars wouldn’t get bored. On nights when we were not playing, we would often still go there and hang out. There was a jukebox full of singles from Rob’s collection. All cool stuff. The regular Funhouse people took a degree of pride in being in an exclusive new inner city scene, far removed from and way cooler than the pub rock scene out in the suburbs. They thought local bands that played the traditional circuit, like AC/DC and Cold Chisel, were hopelessly out of date and square. The Funhouse scene was sort of cultish, in a way. They started wearing our logo, first on patches, then tattoos. Eventually, by about mid 1977, punk aesthetics and dysfunctional behavior started to creep in, and around that time the Hells Angels started hanging out. It became dangerous, and we pulled the plug.

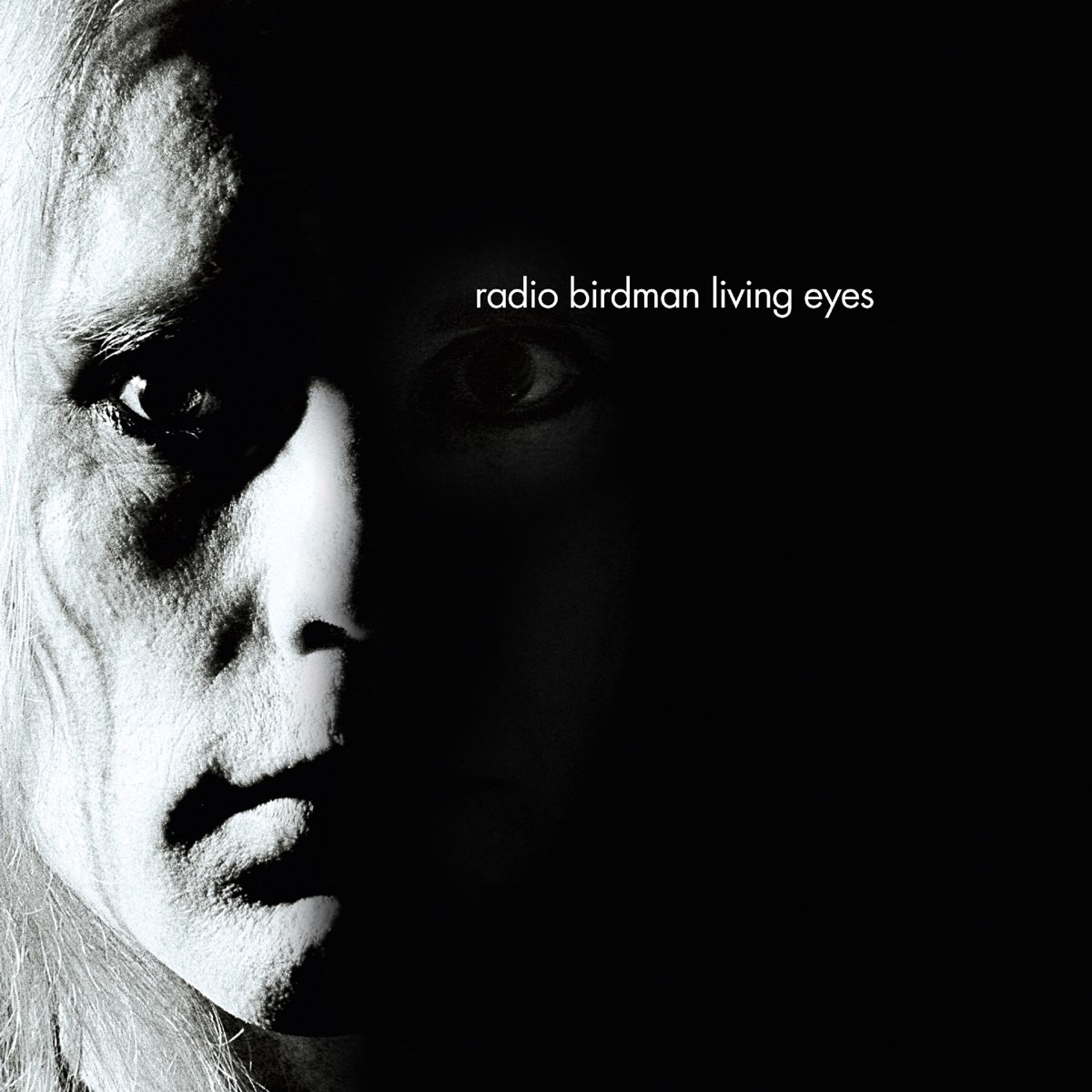

Klemen Breznikar: What were the circumstances around the planned American tour with Ramones and the recordings of your second album, ‘Living Eyes’ at Rockfield Studio in Wales? Why did Sire decide not to release it? The tapes eventually were released in 1981, long after the band’s 1978 break-up.

We were on tour with the Flamin’ Groovies in the UK and Europe. The relationship between Sire and its distributor Phonogram fell over, and we were caught in the middle of it. Our records were in warehouses in the UK and Europe but never distributed to stores. As a result of the financial mess that followed, Sire had to drop many of its artists, including us. They kept the Ramones and the Talking Heads. We had recorded ‘Living Eyes’ at Rockfield for Sire, during a break in the tour, but being dropped from the label it wasn’t considered for release. ‘Radios Appear’ was abandoned in warehouses, ‘Living Eyes’ was cancelled, and we had no financial support. At the same time there were problems within the band. Of course, since we were no longer on the label, the tour with the Ramones was cancelled. After we returned to Australia in mid 1978 Ron, Chris, Warwick and Pip announced that they were no longer interested, and that left just Rob and I. We were back where we started, and so we called it quits.

Klemen Breznikar: Would you like to discuss the ending of the band?

It hasn’t ended yet. We got back together in 1996, and carried on, with a couple of lineup changes along the way. We recorded a new original album in 2006, and did world tours in ’06 and ’07. We’ve been quite active over the last 10 years, playing 30 or 40 concerts a year and are still going, although we haven’t done any gigs since the pandemic.

Klemen Breznikar: All six members went on to other bands. Together with Keeley and Pip Hoyle you formed the Visitors, what was that like for you?

That was marvelous for me. The Visitors was back to the one guitar and one keyboard format, which I like. We had a great singer in Mark Sisto, and an amazing bass player in Steve Harris, who was also playing keyboards in The Passengers at the same time. I am especially proud of The Visitors album, which was recorded essentially live in the studio in one afternoon. The Visitors have gotten back together regularly for tours and occasional benefit concerts, like the Ron Asheton Foundation benefit in Sydney a few years ago.

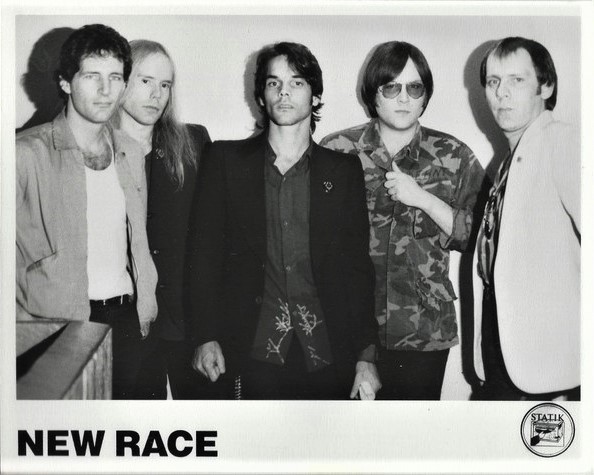

Klemen Breznikar: Together with Younger and Gilbert, you also played in a one-shot touring band called New Race…

When ‘Living Eyes’ was finally released by Trafalgar, three years after it was recorded, we wanted to go on tour in Australia to promote it. Since Radio Birdman no longer existed at that point, I recruited my friends Ron Asheton, from the Stooges, and Dennis Thompson, from the MC5, to put a band together. The tour was successful, and resulted in a professionally recorded live album, ‘The First And The Last’.

Klemen Breznikar: What about the Angie Pepper Band?

That was her follow-on band after The Passengers. It was Angie, myself, Steve Harris, Clyde Bramley on bass and Ivor Hay from The Saints on drums. We played a series of gigs in Australia and started recording an album, but support from the label was withdrawn and it was never finished. The band split up and Angie and I moved to America.

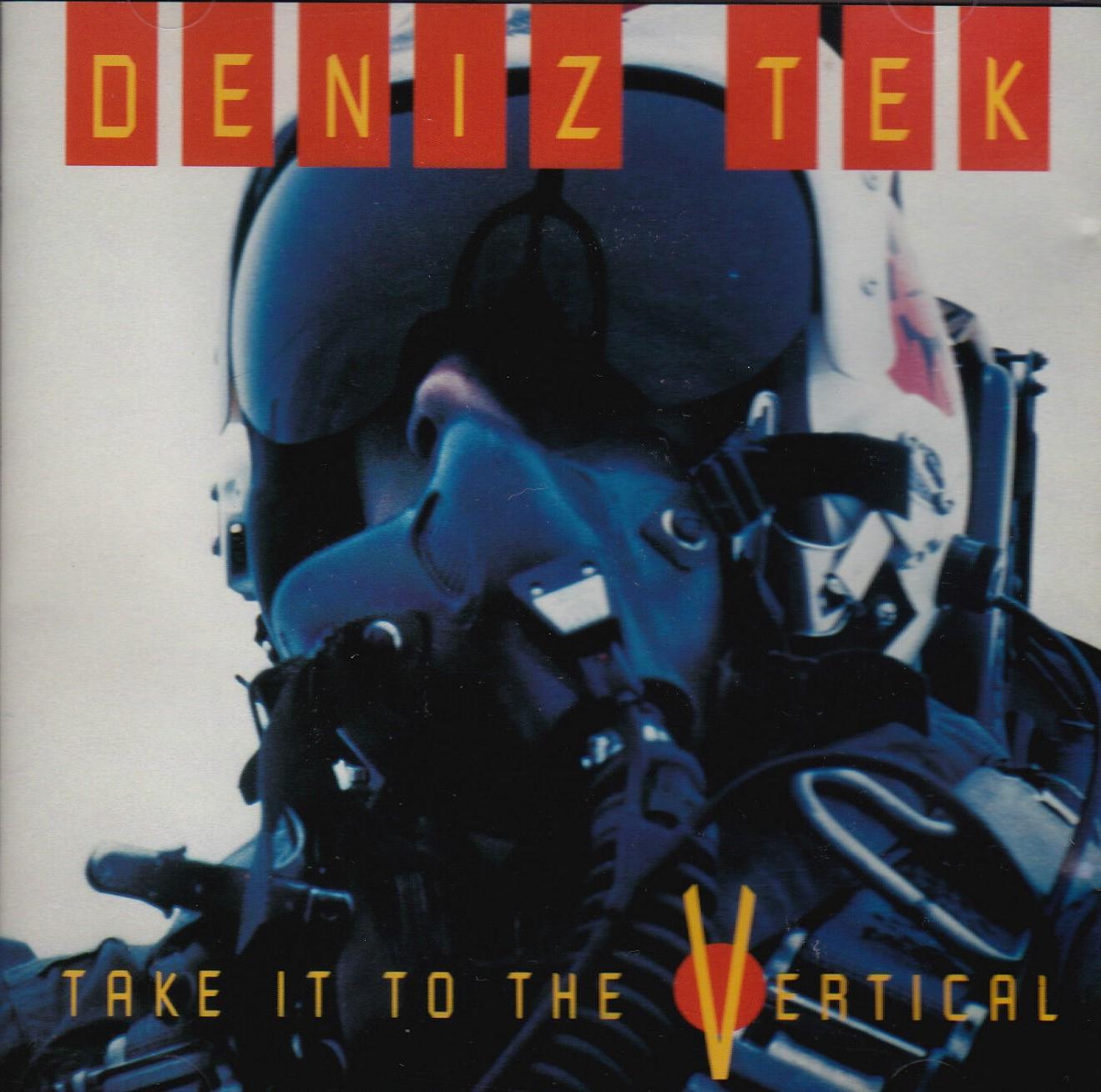

Klemen Breznikar: Would you like to talk about your first solo album, ‘Take It to the Vertical’?

It was my first of many solo albums. Chris Masuak partnered with me on the production, and we recorded the album in 1992 at the historic Sugar Hill Studios in Houston, Texas. Andy Bradley engineered. Scott Asheton, from the Stooges, played drums. Dust Peterson, one of my Marine aviator pals, was on bass. Chris and I played guitars. Chris is also an excellent keyboardist, and he added piano and Hammond B3. Vertical was sort of the “anti-grunge” album, sonically – it was a very clean recording, guitars without effects through Fender amps. As such, it did not fit in with the zeitgeist of the early 90’s. The initial CD release on Redeye/Polydor sold poorly, although it has stood the test of time. It was re-released by Wild Honey Records on vinyl last year, and was well received. It did better in 2021 than it did in 1992.

Klemen Breznikar: You were born to a Turkish father and an American mother and grew up in Ann Arbor, Michigan, do you think that influenced who you became as a musician later on?

I am sure that’s true. Aren’t we usually the product of our DNA and our early life experiences?

Klemen Breznikar: Was it difficult for you to leave the States?

No, I couldn’t wait to leave the country and be out in the world on my own. I saw the journey as a great adventure.

Klemen Breznikar: Were you inspired by Turkish music as well from your father’s side?

No. My dad had mostly left Turkish culture behind when he moved to America. We didn’t speak the language, and we didn’t have Turkish music in our home. My maternal grandmother was a concert level pianist, and she liked to play ragtime. My mother played piano also, especially boogie-woogie. My parents’ record collection tended to be more into Brazilian cool jazz, Bossa Nova, that sort of thing. And my dad liked French traditional pop singers like Leo Ferrer, Edith Piaf, et cetera.

Klemen Breznikar: Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band? Which songs are you most proud of? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

Radio Birdman has played well over 1000 gigs. Some of the highlights are:

Paddington Town Hall, Sydney 12/12/77 : This gig was probably at the peak of the band’s power in the 70’s, just before we left for the UK. There’s a good recording of it, the LP captures much of the magic.

Hope and Anchor, 1978: The only time the band ever played three encores, because they wouldn’t let us leave.

Magic Stick, Detroit, 2006: Hometown gig that went off, wild crowd, reminiscent of the energy at the Grande Ballroom in the 60’s

Bordeaux, 2018: Sharing the stage with the Flamin’ Groovies again, after 40 years.

I’ve got over 300 songs published, most are not in the Radio Birdman back catalogue. Of those that are, it’s hard to say. If you asked me on a different day, the answer would be different. The ones that come to mind at this moment are: ‘Descent Into The Maelstrom,’ ‘Non-Stop Girls,’ ‘Alone In The End Zone,’ ‘Hanging On,’ ‘Heyday,’ ‘We’ve Come So Far (To Be Here Today)’.

Klemen Breznikar: Is there any unreleased material by Radio Birdman?

Yes, there is. I went through dozens of hours of studio recorded tape to select material for the box set (2014). I only used a fraction of it.

Klemen Breznikar: What are some future plans and what currently occupies your life?

I’m starting a European tour in a couple of days, to promote and celebrate ‘Long Before Day’. After that, I’ll be writing some new songs. Hopefully I’ll be playing some more tennis with James Williamson, who happens to be a neighbour. And above all, spending time with family.

Klemen Breznikar: Thank you. Last word is yours.

Thanks for the questions, and for your interest. Peace.

Roy Phillips and Klemen Breznikar

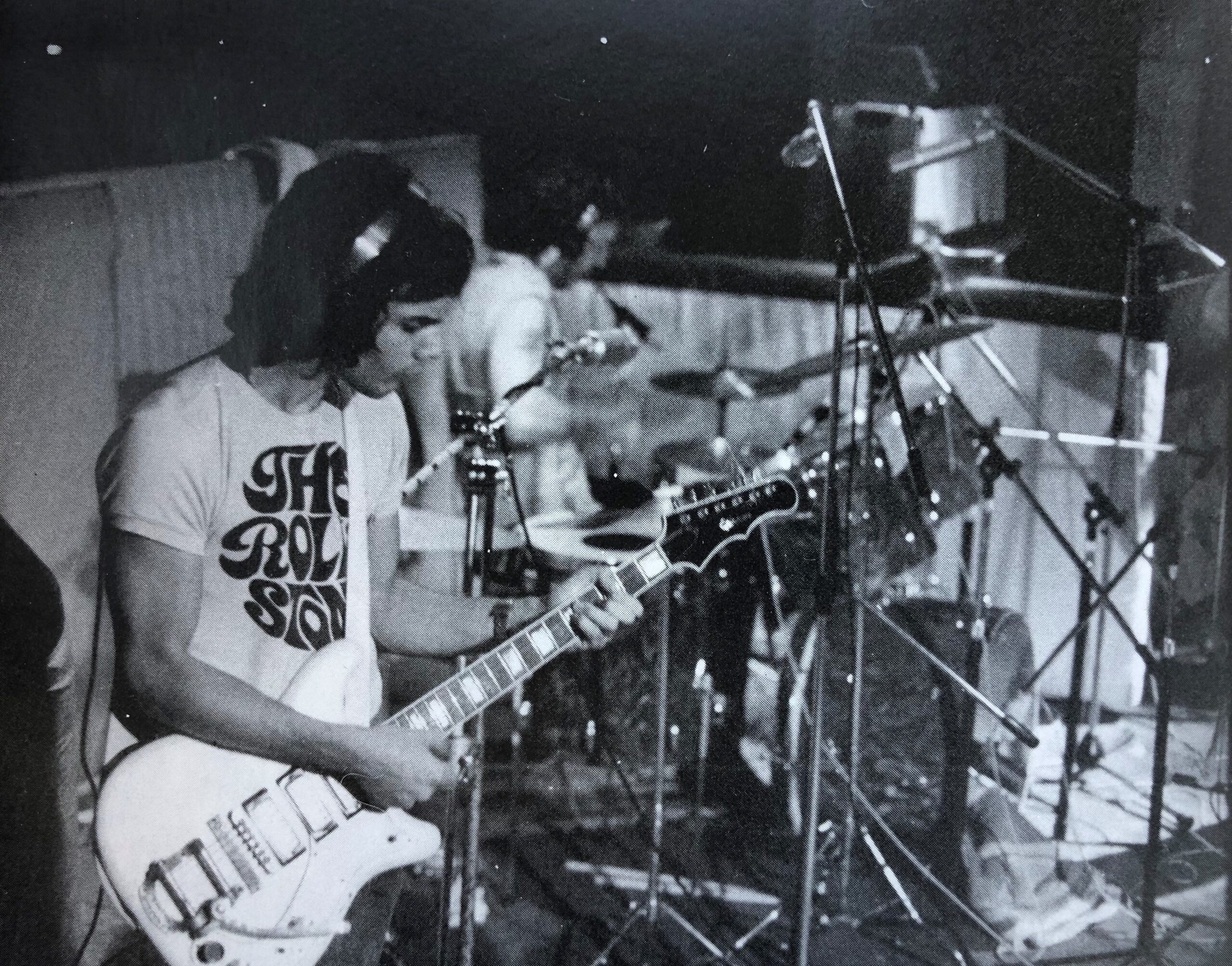

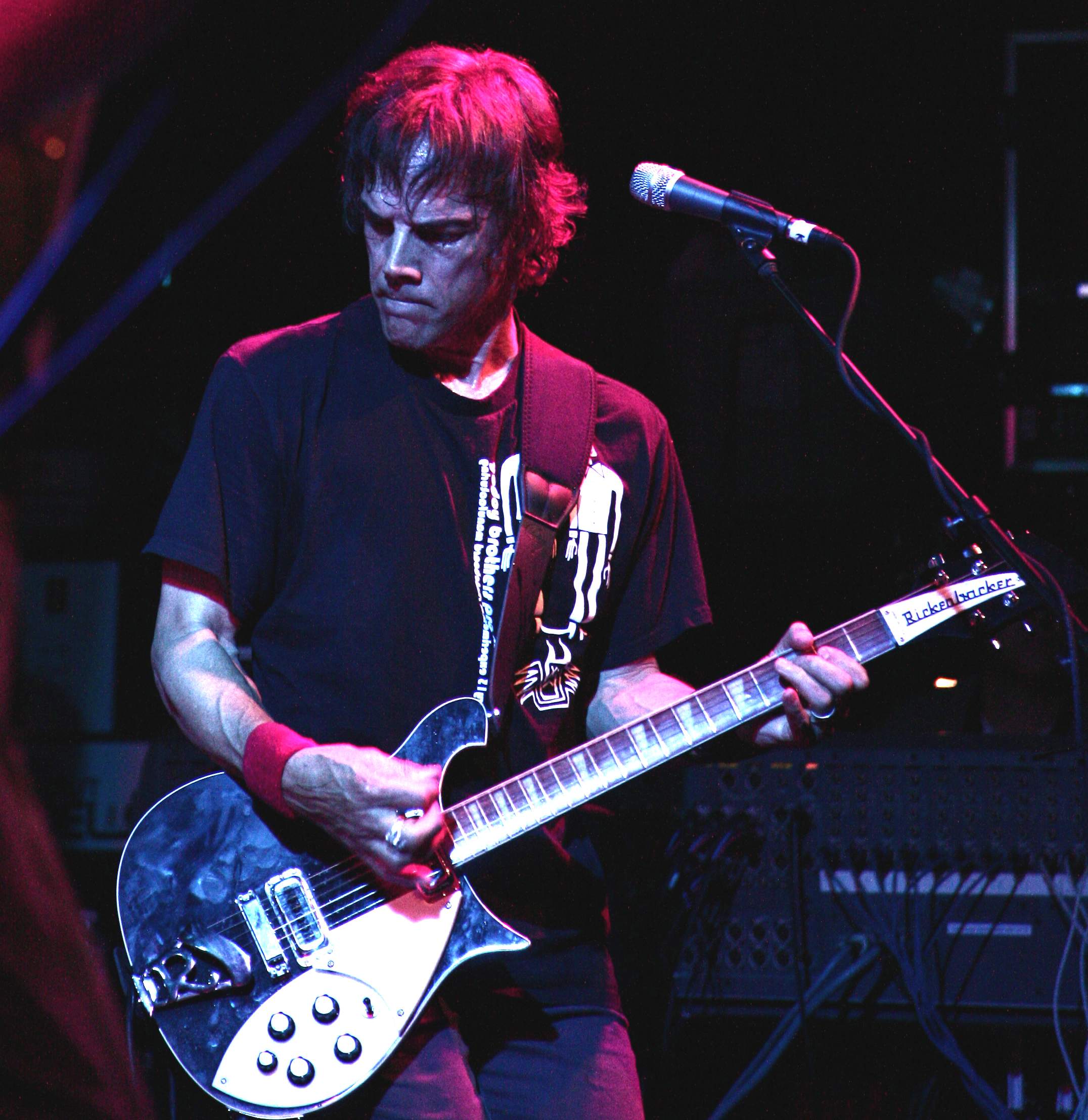

Headline photo: Radio Birdman in 1976 | Photo by Bob King

Deniz Tek Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Bandcamp / YouTube

Radio Birdman Official Website / Facebook / Instagram

Wild Honey Records Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube

Career Records Official Website

Klemen, thanks for the interesting interview with Deniz Tek. I have all the bands mentioned and shown here on vinyl or cd. The Aussie scene is one of the most interesting. Especially in the late 70s to mid 90s. I think i have more than 1,500 lps & cds from Aussie including NZL. Deniz Tek and i are almost the same age. I envy him for the many interesting bands has seen live. I’ve also seen a lot of bands live but very different ones.

Nice interview, Tek’s personality comes across as full and controlled as Radio Birdman’s music :-). The site has been on a roll lately; it’s good to see the underground non-mainstream legends featured here. Tek was one of the finest guitarists in Rock and he and Radio Birdman rocked like no other during their heyday.

Great interview. It’s fantastic that Deniz considers the Hope and Anchor gig a highlight because the documentary generally downplays that UK tour but I was at that gig and it bloody wonderful