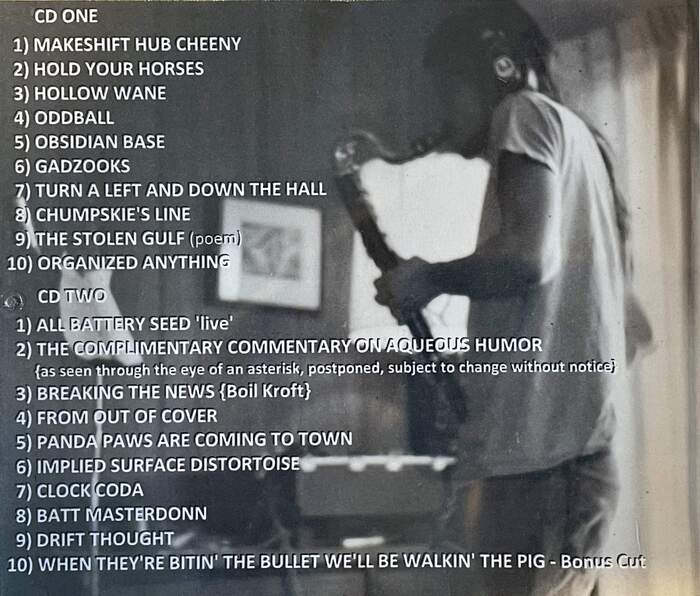

The Miller Brothers | Blurring the Lines

The Miller brothers’ musical journey spans from the psychedelic experiments of Sproton Layer to the genre-blending creativity of the Fourth World Quartet, through the raw energy of Detroit’s punk scene with Destroy All Monsters, and ultimately to the influential indie rock sound of Mission of Burma, and it continues even today.

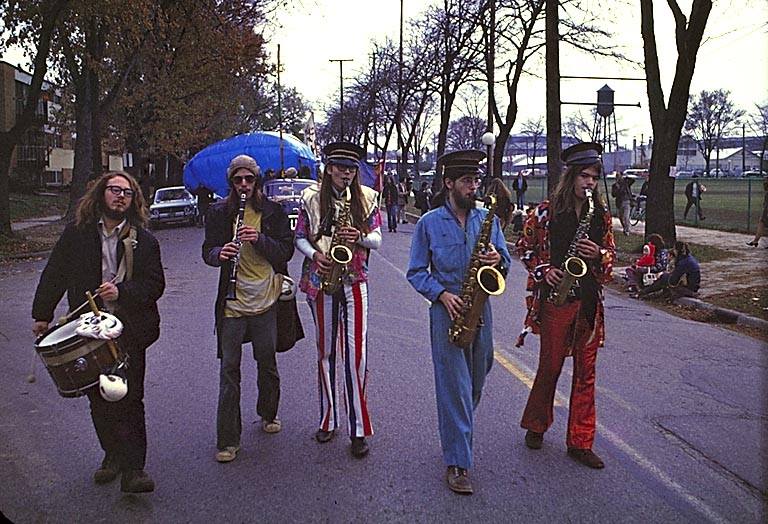

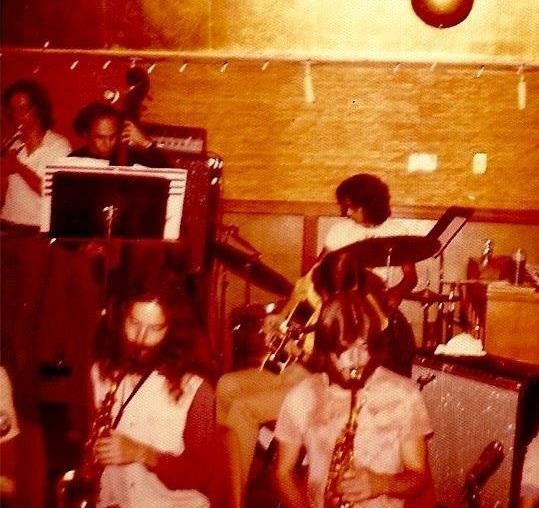

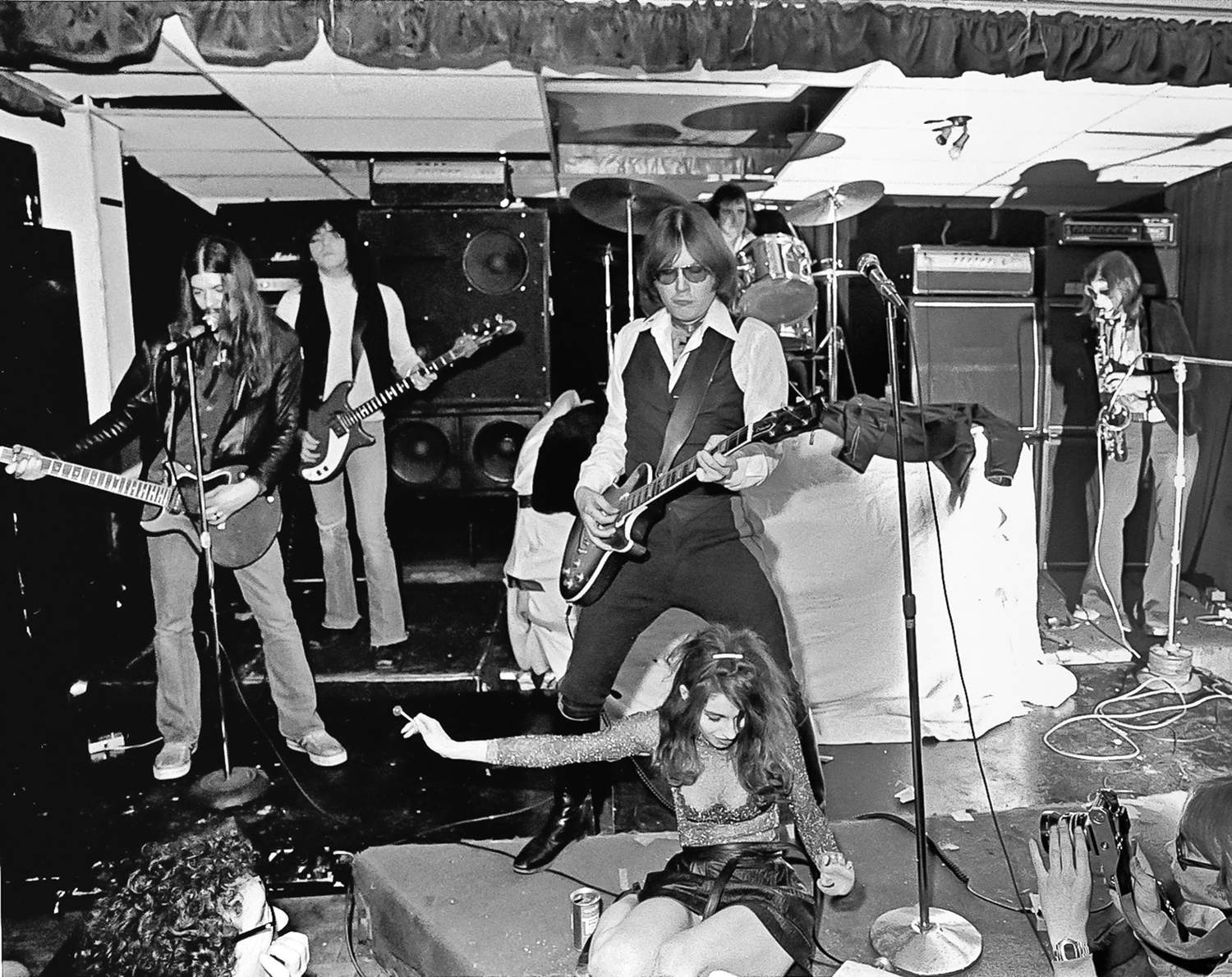

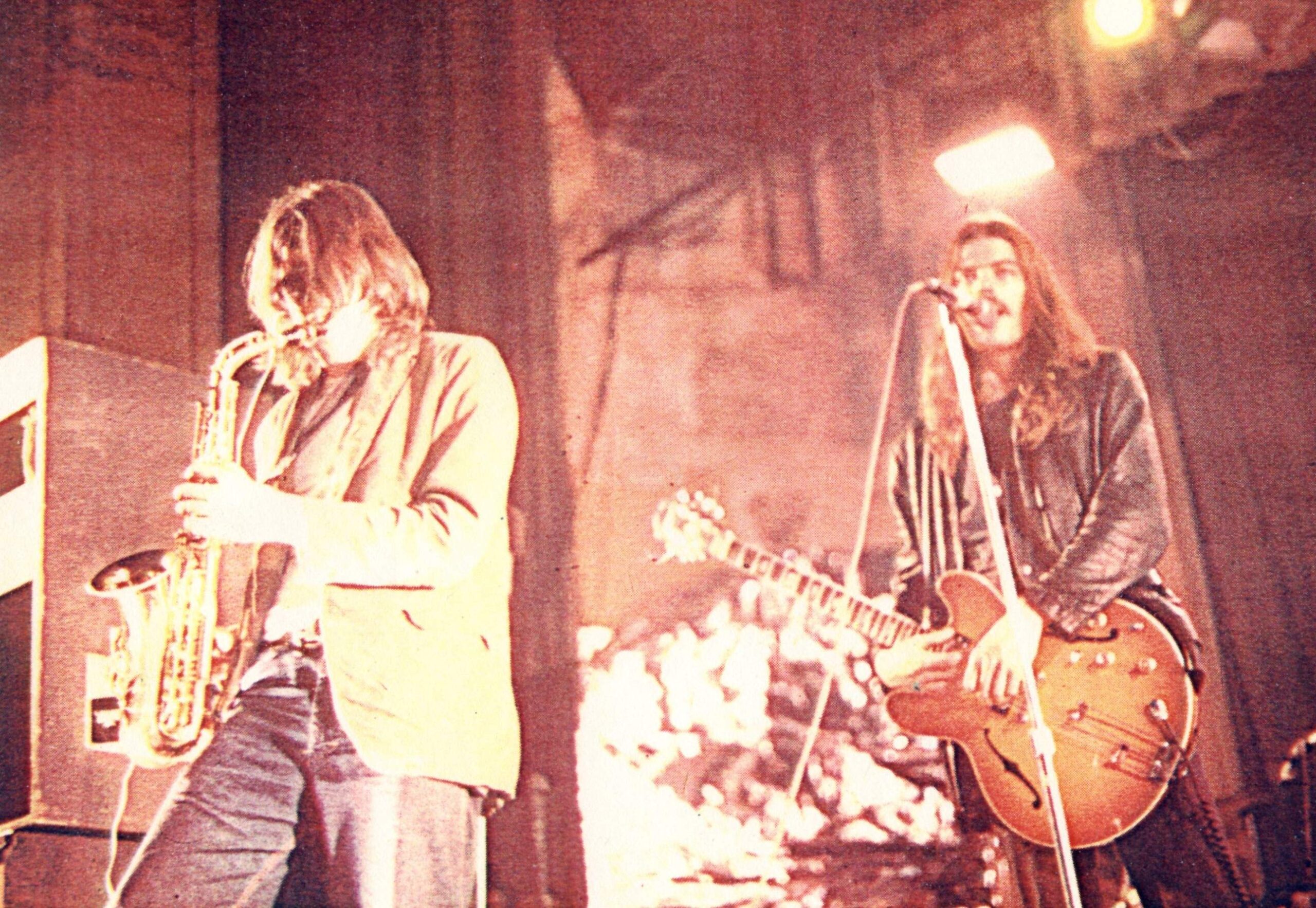

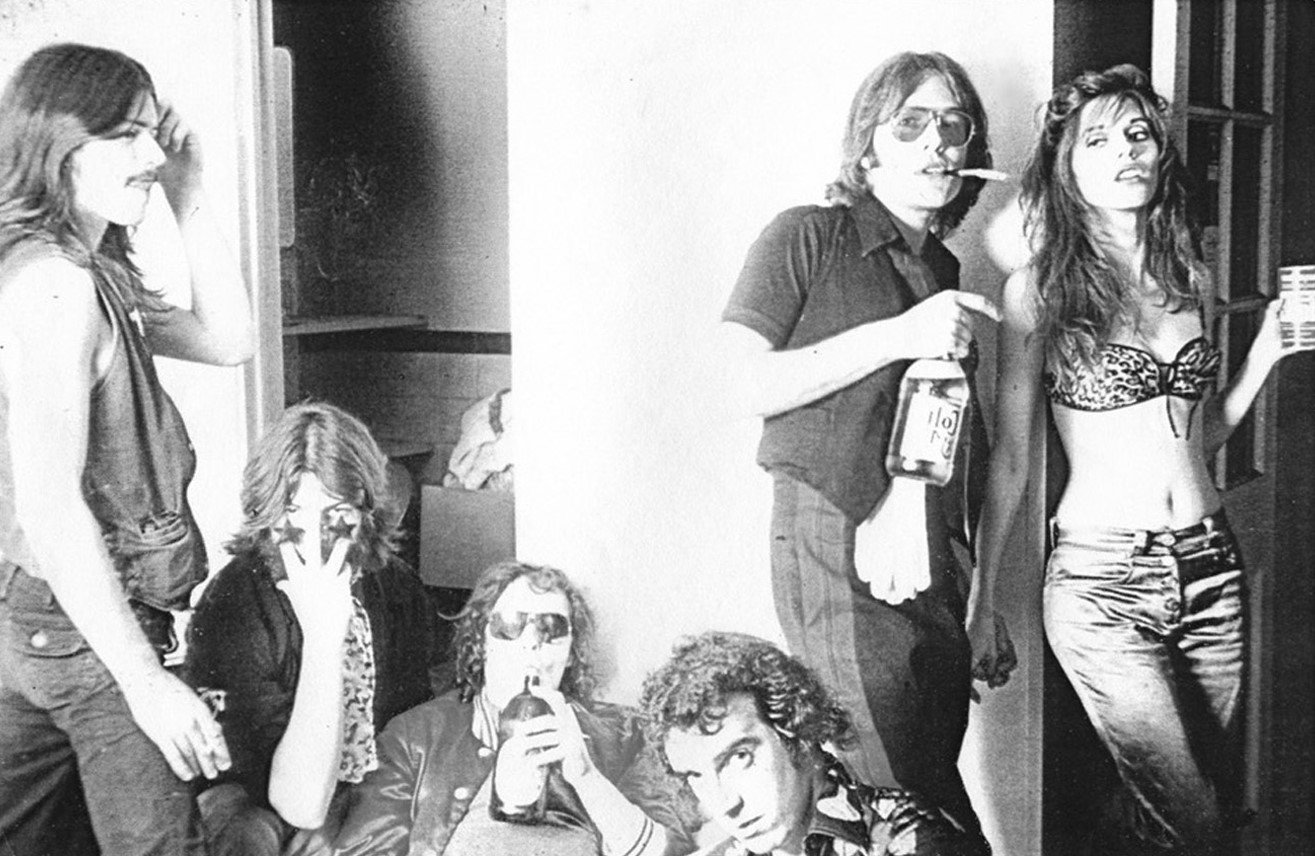

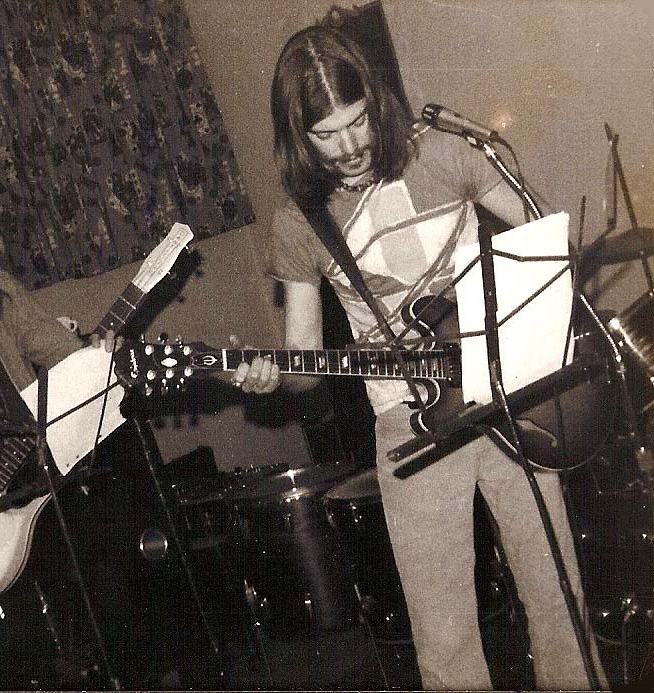

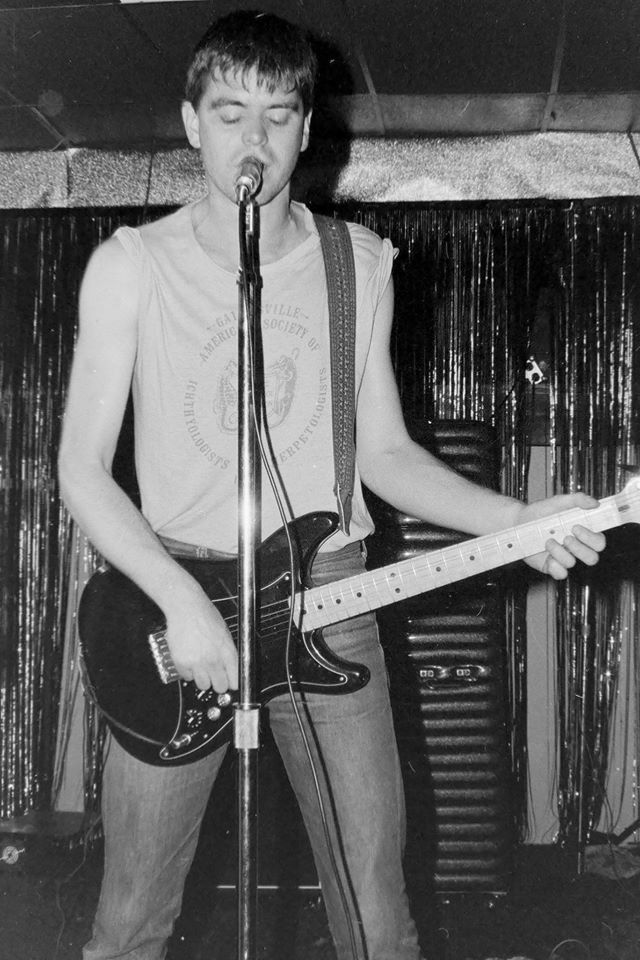

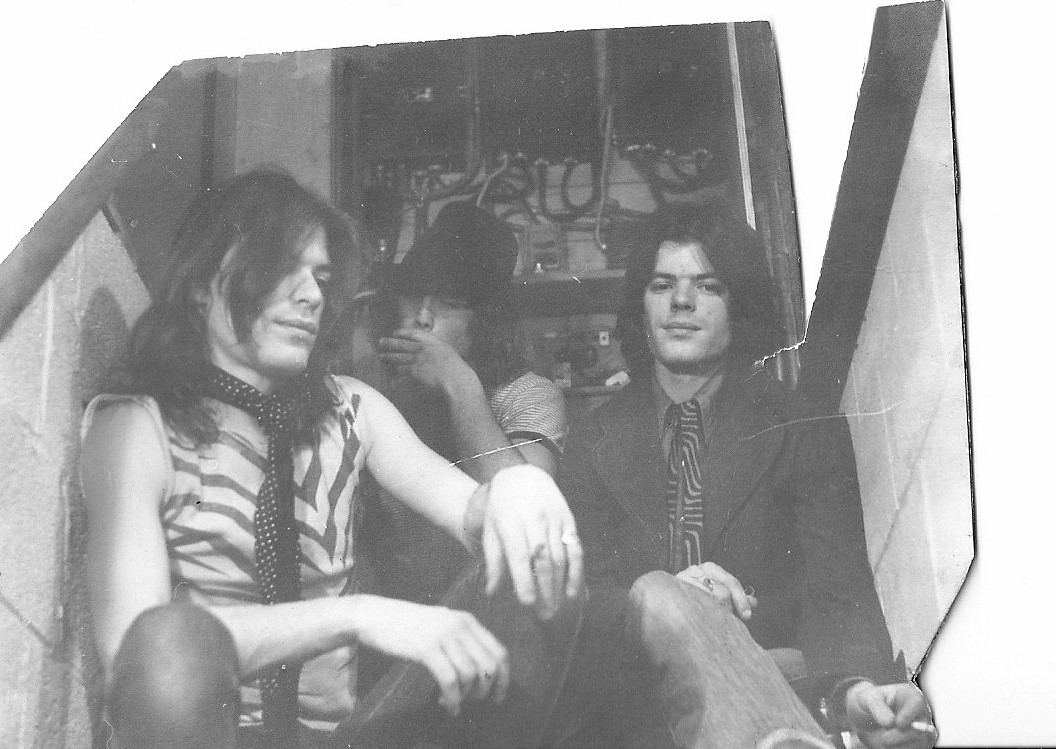

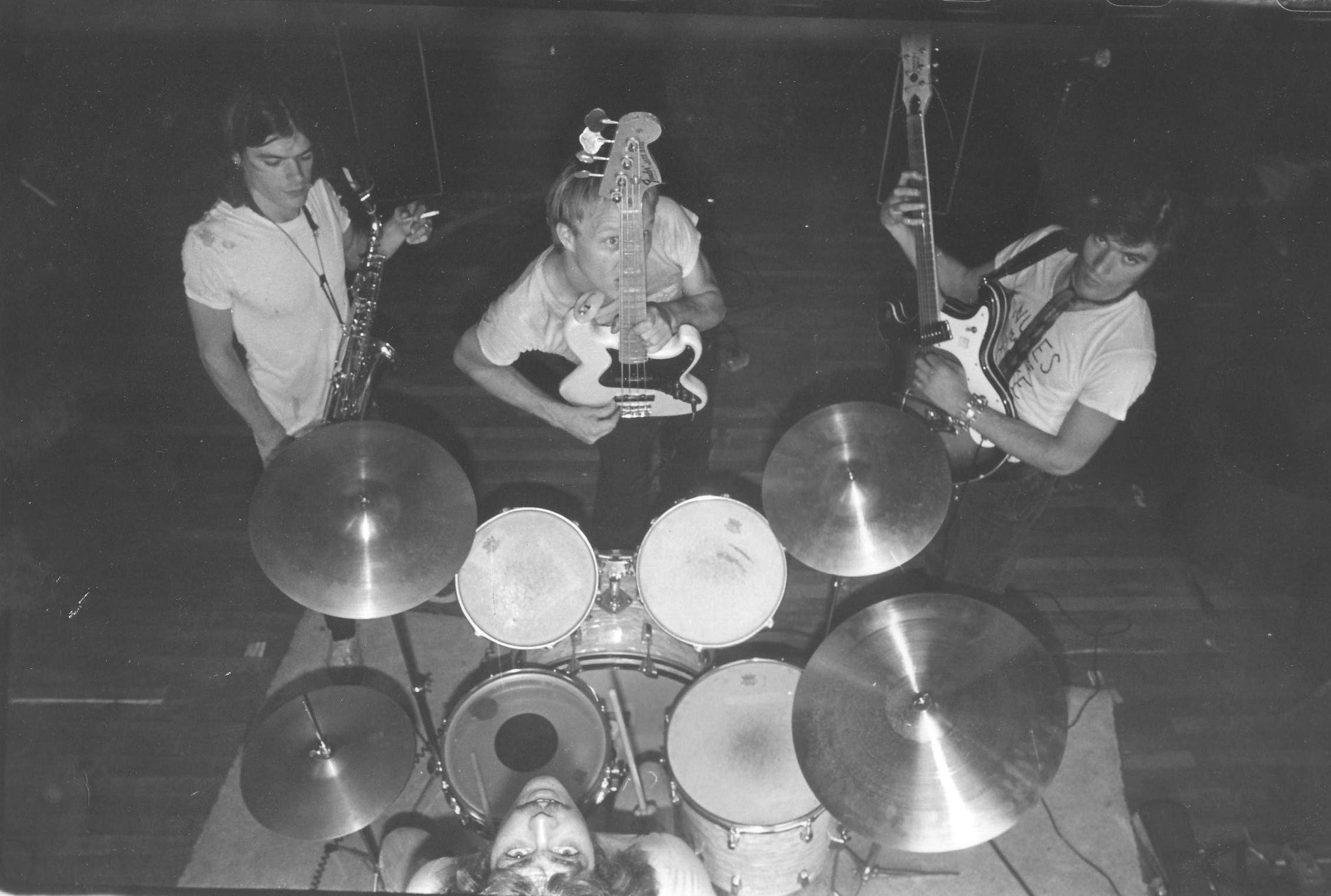

In the late 60s, the Miller brothers were just kids in Ann Arbor, Michigan, soaking up the sounds of the Summer of Love. By 1969, they had already formed Sproton Layer, their all-original rock band, while keeping it cool at free MC5 concerts and avant-garde shows at the University of Michigan. Fast forward to 1975, and the brothers were mixing it up at art school, forming the Fourth World Quartet—a blend of freeform improvisation, classical, and jazz—along with their buddy Jack Waterstone. The quartet took risks, arranging pieces by Stravinsky and the Art Ensemble of Chicago with a flair that only true innovators could muster. By 1977, the punk scene was on fire, and Laurence and Benjamin joined Destroy All Monsters, while Roger co-founded Mission of Burma, a band that would become a cornerstone of indie rock’s future.

“Unusual musical segments spun as free association”

It’s wonderful to have you back. It’s been over a decade since we discussed the Sproton Layer. What projects have you been working on in the last ten years?

Roger: Oh boy…

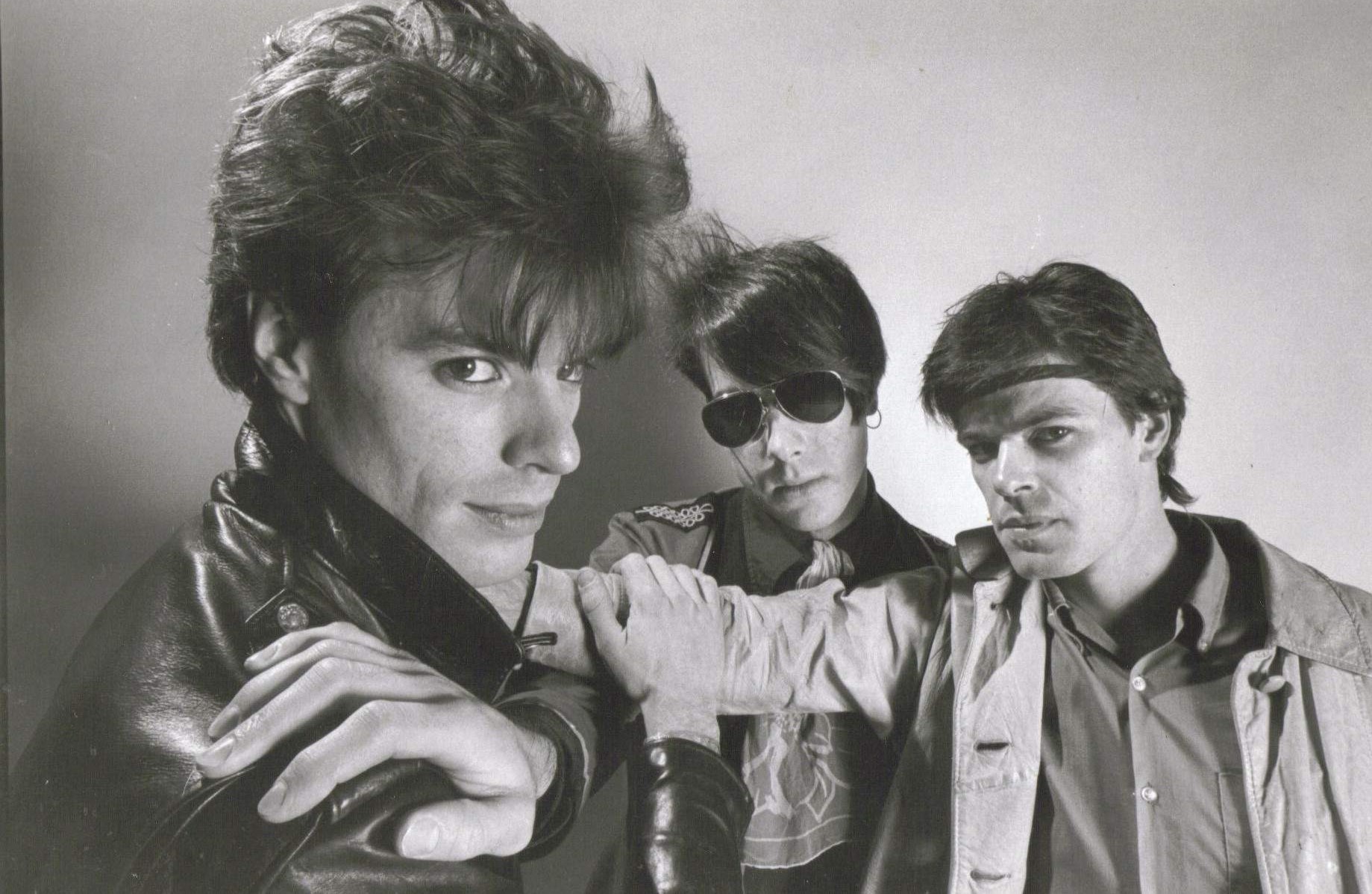

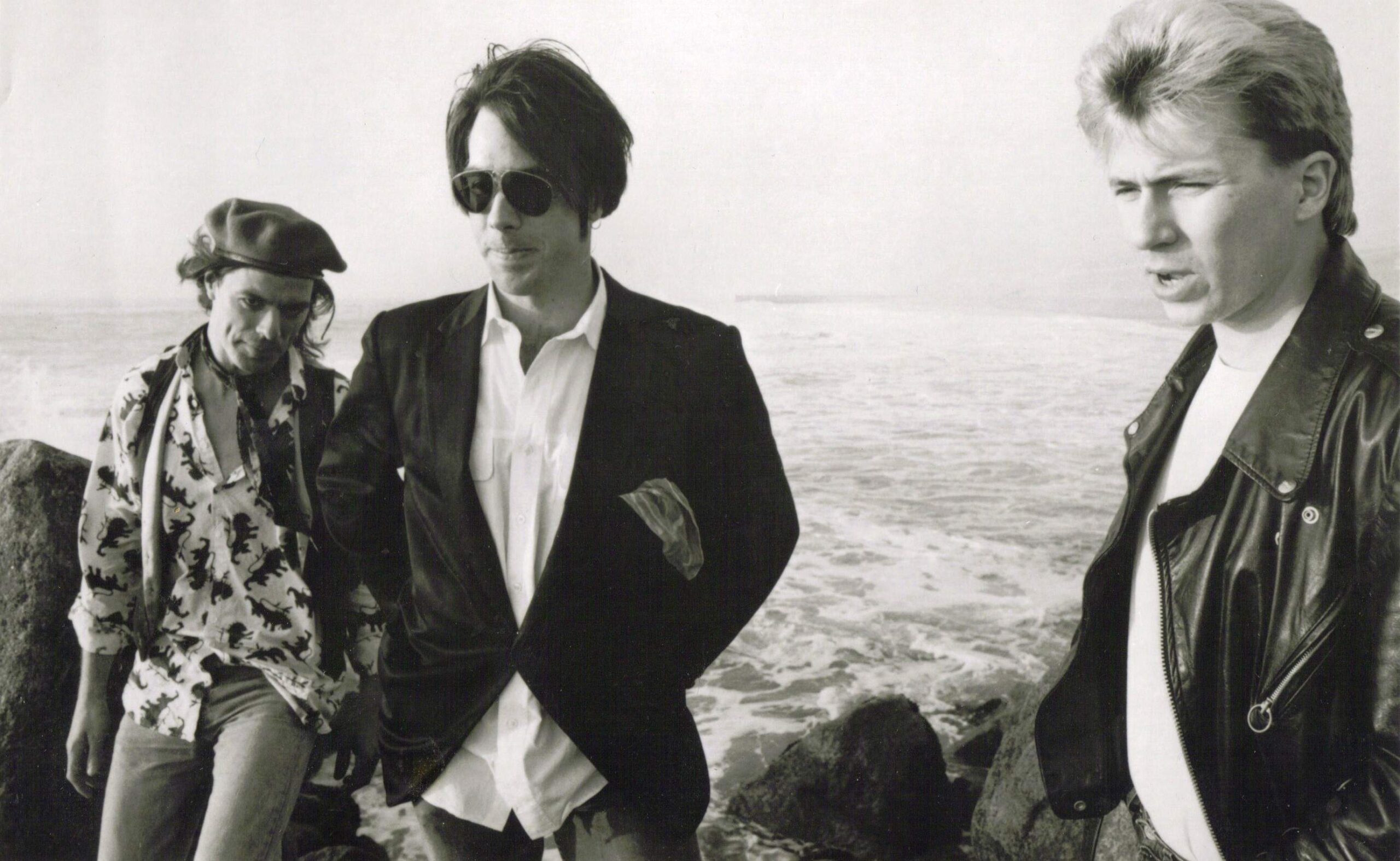

Mission of Burma, second incarnation:

We finally stopped playing in 2015. There was no angst about it; the band had run its course, but we had a blast. At least two of our reunion albums, ‘The Obliterati’ and ‘Unsound,’ are, in my opinion, quite good.

Alloy Orchestra/Anvil Orchestra:

I kept performing in this trio to silent films, but we ground to a halt during COVID. Afterward, the band underwent a slight change, and we are now called The Anvil Orchestra. I am now the manager, as well as a keyboardist and co-composer. We don’t play quite as much as before, but we’re still quite active. Our first new score premiered in Amsterdam a few years back.

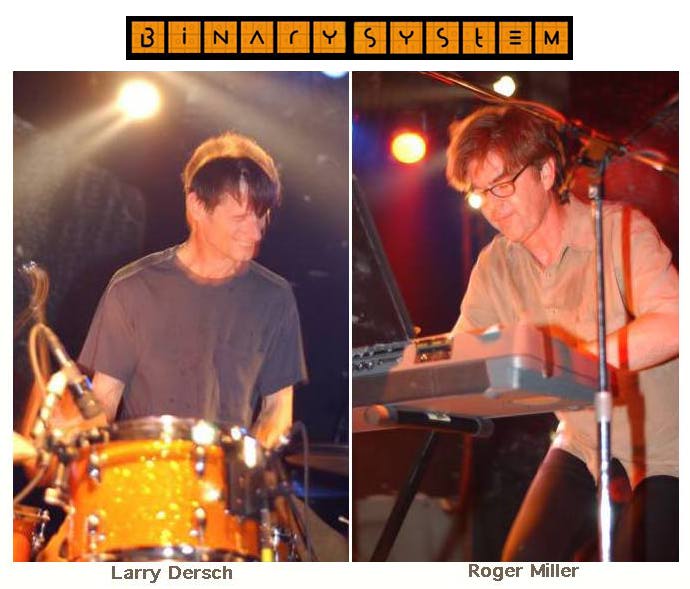

Trinary System:

This is the rock trio I started just before Sproton Layer reformed in 2013. After Sproton Layer’s brief but bright resurgence, Trinary System resumed activity. We recorded an EP, an LP (‘Lights in the Center of Your Head’), and we’re currently wrapping up our second—and likely last—LP. I love this band, and if I were 30 years younger, I’d be out on the road with it. We’re still good friends, and if required, we could get back into action.

M2:

This project preceded Sproton Layer in 2012. It was Ben with his “multiphonic guitar” rig and me on prepared piano. We only played a few shows in NYC and Boston, but we recorded an excellent avant-garde/ambient LP, ‘M2: At Land’s Edge,’ on Feeding Tube Records. The music was entirely improvised.

Chamber Music Composing:

This aspect of my work ramped up. In 2015, my composition ‘Scream, Gilgamesh, Scream,’ a setting of The Epic of Gilgamesh, premiered at the New England Conservatory, featuring me on electric guitar, along with soprano and baritone voices, keyboards, strings, and winds. It was quite rippin’. A few years later, in 2018, I had a concert devoted entirely to my chamber music at Tufts University. I still compose in this style, and a concert featuring some of my chamber music is scheduled for 2025 at the ICA Boston and MassMoCA.

Transmuting the Prosaic:

My first art installation went up at the BMAC in Brattleboro, VT, just in time to hit COVID (March 2020). Despite that, it was successful, and in 2022, it moved to 3S Artspace in Portsmouth, NH, with a write-up in the Boston Globe. The installation involves my “Modified Vinyl” creations, which play with visual and audio aspects of records in a Dadaist fashion. It also includes my film, The Davis Square Symphony, which I filmed in Davis Square, Somerville, MA, across all four seasons. Using a post-John Cage aleatoric composing technique, I turned the movement of vehicles and pedestrians on the screen into an orchestral score.

Dream Interpretations for Solo Electric Guitar Ensemble:

This project started in 2019, and the first album, ‘Eight Dream Interpretations for Solo Electric Guitar Ensemble,’ was released in 2022 on Cuneiform Records. It combines three major threads of my creative work: my interest in dreams, my exploration of the electric guitar’s boundaries, and my fascination with live looping. This is a solo performance blending acute psychedelia, high-level composing, and a passion for live performance. I have played seven shows since the album’s release, and the response has been very enthusiastic. The album reviews were also exceptionally positive, just as I had hoped.

“Unplugged” Shows:

I’ve done several solo electric guitar/vocal shows. I performed two in 2023, and they were well-received. In these shows, I draw from my entire career, and if Trinary System doesn’t continue, I might write songs specifically for this setting. With a simple looper, I can improvise over simple themes as needed.

A Night of Surrealist Games:

I continued my Surrealist Games Night at various venues, where I play the Surrealist Host and guide participants through a variety of surrealist games from the 1920s and 1930s. These events encourage creativity, even among those who think they aren’t creative, and I find great joy in facilitating this process.

1975: The Fourth World Quartet:

Lar, Ben, and I released ‘1975: The Fourth World Quartet’ in 2022 on Cuneiform Records.

Ben: In 2013, I recorded my first symphony with The Sensorium Saxophone Orchestra—a 50-minute composition with 12 saxophones, from bass to soprano, and 2 drummers. Shortly afterward, I recorded a version of ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ and ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ with my son, Benjamin, as engineer and drummer. I meticulously notated all the tape loops Paul McCartney used in these songs so that you can hear all the loops, but played on saxophones! I’m particularly proud of this 45 rpm record released on Abaton. That same year, Sproton Layer had its reunion, performing in Ann Arbor, Detroit, East Hampton, and NYC. It was a lot of fun!

The following year, while preparing to leave NYC, I premiered ‘Planet X’ with The Magnetic Tape Operatives—4 humans, 10 tape machines, and 6 guitar amps. This analog fiasco was a 20-minute, time-structured composition featuring tape hiss, prerecorded transistor radio mis-frequencies, found sound, forced variations of tape playback speeds, and internal feedback.

I moved in with Laurence to Ypsilanti, MI, and started a recording project called Exploded View in the summer of 2014. Wolf from the German psych-rock label World in Sound, which had recently re-released Sproton Layer’s ‘With Magnetic Fields Disrupted,’ asked me to record a psychedelic rock album for his label, as Sproton Layer had declined that option. Laurence and I decided to create songs we had written during the same time period, from 1970 to 1972. An EP download is available on Bandcamp. A full-length LP is ready to release.

Laurence: The Mister Laurence Experience

This was my alternative rock music trio for children. We had been together for about five years. By 2013, it was coming to a close, but I continued for another two years as a solo performer, just as I had when I started as a children’s entertainer in 1998. After a while, I lost interest in children’s music and refocused on so-called “grownup” music.

Exploded View

Wolfgang, the owner of the German record label World In Sound, contacted me out of the blue about Sproton Layer. I gave him Roger’s contact information, and long story short, he released our 1970 recording ‘With Magnetic Fields Disrupted’ in 2011. Wolfgang was so excited about our reunion that he flew in to witness our showcase gig at Ann Arbor’s The Blind Pig in 2013. He was so impressed that he promised to finance a new album. Unfortunately, after our brief stint of concerts here and on the East Coast, Roger decided to focus on his other bands, Mission of Burma and The Trinary System, stating that they took precedence. Ben and I were, of course, disappointed. Wolfgang then offered Ben the opportunity to release a new psych-rock LP. This led to the formation of our twin-based “recording group,” Exploded View.

Ben moved back to Ypsilanti, Michigan, moving in with me in the spring of 2014. We brainstormed various ideas, focusing mainly on songs we had both written back during the Sproton Layer days. We rehearsed enough material for an LP and recorded a basement demo for Wolfgang, who liked what he heard and expressed interest in our future studio recordings.

However, for reasons unknown to us, Wolfgang only financed part of our studio costs and eventually pulled out. Ben and I finished the overdubs in our home studios over the next few years, and then the pandemic hit. Our LP, ‘Galavan,’ is now fully mixed and ready for release, awaiting label interest.

Larynx Zillion’s Novelty Shop (this millennium’s version)

I finished my family-friendly musical film, Growing Grapes for the Future, in early 2014. It featured The Mister Laurence Experience and music videos performed by a fictitious band called Lammy Rillerson and the 3D Newz.

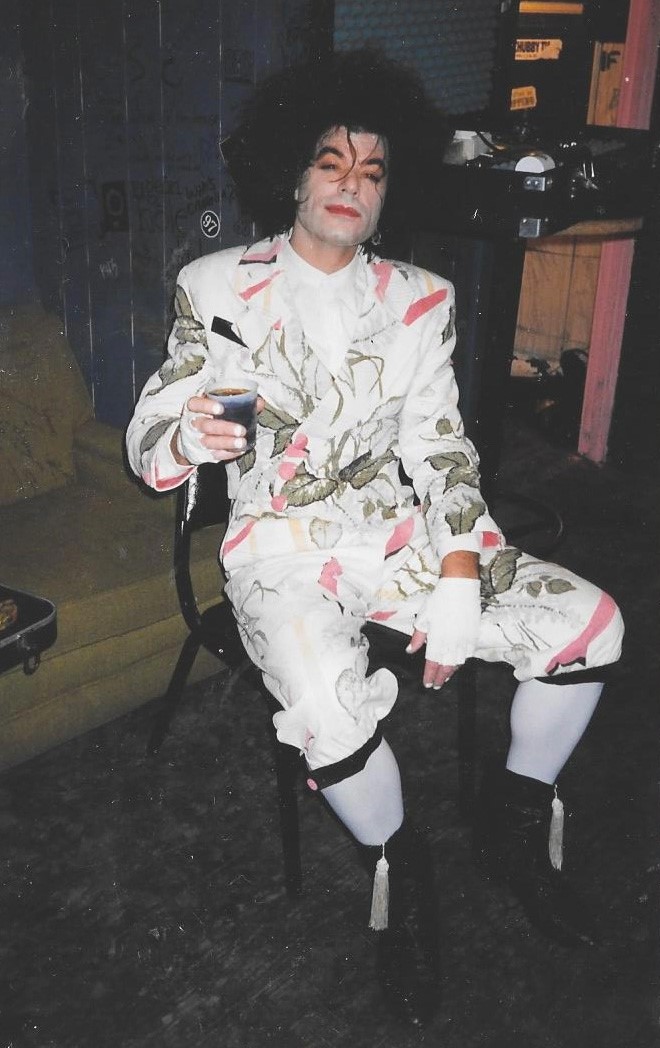

I had already started scripting my next film, Aqua Lung Secret ~ Operation: Duplicate, which featured Zillion the Clown, the alter ego of lead role actor Tinn Parrow. Zillion the Clown was a stage persona I had created in the 1990s for my avant-garde glam rock band, Larynx Zillion’s Novelty Shop. However, I lost focus and went down a four-year rabbit hole.

In 2015, I spent time digitizing all the analog master tapes of the original band, which had been recorded from 1994 thru 1998 but never released. I also digitized some live video footage of the group, which I uploaded onto my YouTube channels. This inspired me to reinvent The Shop with new members and a different approach. We performed locally a few times, resulting in a small collection of home recordings. These were released as an EP CD titled ‘Open/24-7,’ from which I created two CD singles that paired surprisingly well.

Empool (this millennium’s version)

I had been trying to get Feeding Tube Records interested in some basement tapes of my garage noise band, Empool. This group I formed in the fall of 1976, which merged with Destroy All Monsters in the spring of 1977. Feeding Tube finally agreed to release the collection in 2017. It was an eclectic mix of existential Dada-inspired songwriting and freeform psychedelic improvisation, with many of our jam sessions supported by prerecorded “found sound” via analog tape.

After our LP, ‘Does Do Did Done,’ was released in June 2018, Ben suggested we try reuniting the group. However, none of the original members still lived nearby, and recruiting new musicians proved futile. So Ben and I pulled our resources together as a duo outfit and started from scratch. I digitized some of the original backing tapes from the late ’70s and created new recorded sound design for our new material.

Empool performed locally from 2018 through 2019 to surprisingly open-minded crowds. We sold merch at every show. But then the pandemic hit, forcing us to cancel a mini-tour that Ben had just booked. The new version of EMPOOL was a lot of work, involving multiple guitars, a multitude of foot pedals, and video projection equipment. We also had to be very careful with timing during live performances, given the complex setups.

That said, we did record and release a collection on my label, FarFetched Records, and on Bandcamp, titled ‘Instrumental.’ Another full LP, ‘Context vs. Association,’ is fully recorded and awaiting label interest.

Laurence Miller And The Love Maniacs (2017-2021)

I felt the urge to create a hard-driving, old-school R&B band, blending original music with classic R&B at a 50/50 ratio. The vibe was akin to Fats Domino with a harder edge. We recorded a 15-song CD just as the pandemic hit, but unfortunately, the timing couldn’t have been worse, and we had to call it quits (Bandcamp link).

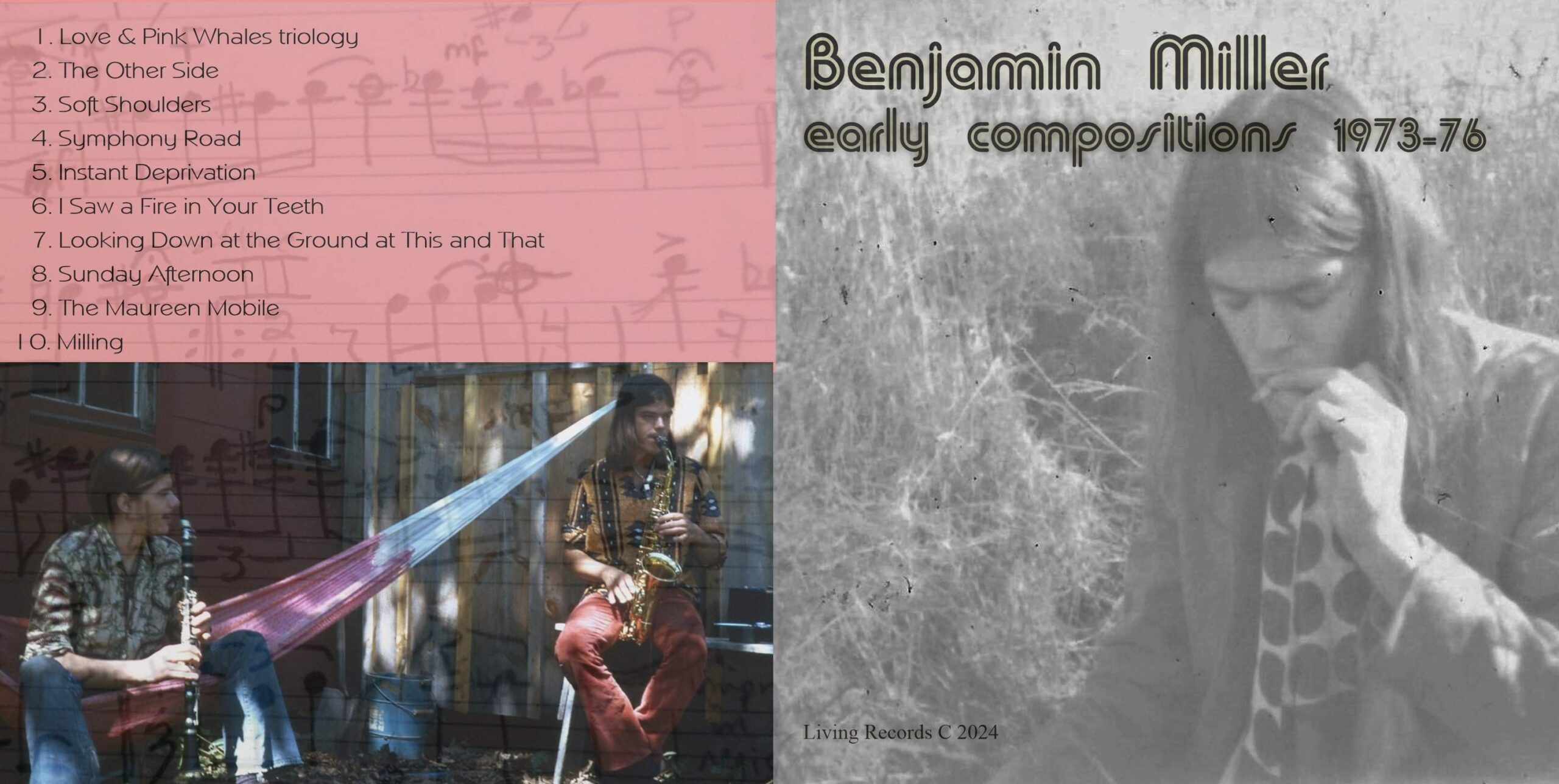

Miller Twins Early Compositions (1973-76)

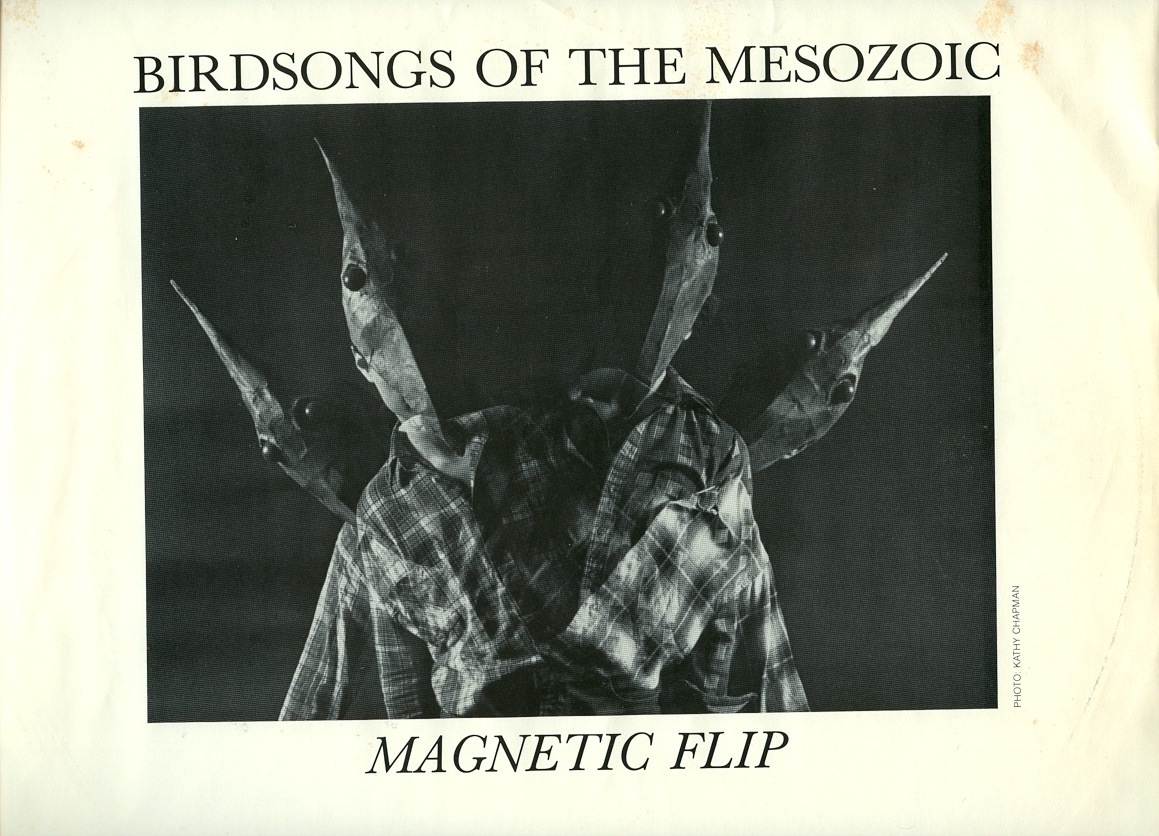

One of the most exciting and satisfying experiences this past decade came from the attention Cuneiform Records paid us. Roger, Ben, and I had formed a neo-classical freeform jazz band while attending college in 1975 called The Fourth World Quartet. A full recording of the band was unearthed, digitized, submitted, and released by Cuneiform in June 2021. Cuneiform’s interest stemmed partly from the material’s connection to Bird Songs Of The Mesozoic. Roger’s compositions were also performed and recorded by Bird Songs.

This surprise interest inspired Ben and me to find a live recording of the second version of the quartet, which had Denman Maroney on piano, replacing Roger. Cuneiform released this batch the following year, much to our delight! This then motivated Ben and me to dig up all our mid-70s compositions that had never been properly recorded or performed. We spent over a year practicing and recording the material, reimagining how it might have originally sounded with the right musicians. With the help of some talented musician friends, we finished and submitted the collection to Cuneiform Records. It was accepted and released in September 2023.

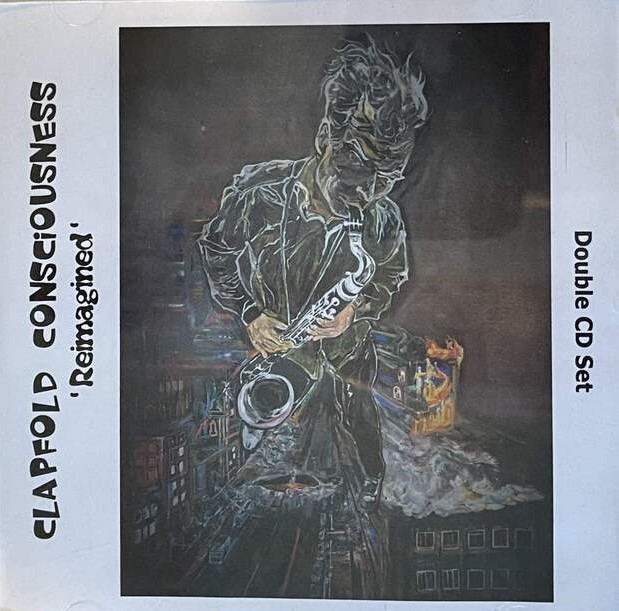

As a result, Ben and I now have our own horn-based ensembles, playing many of the same compositions as well as new material. My new band is called Tinn Parrow and his Clapfold Platune, while Ben’s is called The Eleventh Hour. Who would have thought?

Back when we discussed it, none of us could have predicted the world situation we ended up in: the pandemic, raging wars, social injustice. Sadly, history repeats itself. As a musician, how did you spend the lockdown? Was it a difficult period for you?

Roger: The Negative:

My art installation opened on March 15, 2020, just as COVID kicked in, so only about 1/4 of the people who would have seen it were able to attend. Additionally, my concerts for my Music for String Quartet combined with Solo Electric Guitar Ensemble, which were scheduled for that April, were also canceled. I’m still trying to get those concerts back up and running.

The Positive:

I live on a mountainside in Vermont, which is incredibly beautiful. During lockdown, we would meet our neighbors by the pond, keeping a 10-foot distance from each other. It was a pretty ideal way to spend the lockdown. The PUA funds (gig money) allowed me to actually save some money while I composed extensively, focusing on chamber music and my Solo Electric Guitar Ensemble. So in that respect, it really wasn’t too bad.

But the truly positive thing was this: there’s a world-class studio in Vermont, just 20 minutes from me, and the head engineer is a big fan of mine. No bands could record during COVID, so I rehearsed my Dream Interpretations work in the big room while he worked in the control room. Then I asked if I could record my Dream Interpretations album there, and since no one else could come in due to COVID, I could record without a mask in the main room (they had separate air conditioning systems). I ended up recording my ‘Eight Dream Interpretations for Solo Electric Guitar Ensemble’ album during COVID. Crazy, right? The studio would have been empty otherwise, and we got along great.

So, while some things were very weird during COVID lockdown, many opportunities opened up.

Ben: In 2020, I became fully aware of our government’s use of propaganda, especially in relation to the Covid-19 fiasco. The masses drank the Kool-Aid, much like they did with the 9/11 trauma (which had countless red flags), propelling this country into places we’d rather not admit to. This is basically what the U.S. has been doing from the start—invasive actions in other countries, destroying their cultures for monetary gain and global control.

As a musician, my way of coping was to record ‘Thought Crime.’ I invited my good friend and excellent drummer Jarrod Ruby, who played with me in Third Border, to join in. Our collaboration, Miller-Ruby, came together easily—this time focusing on songwriting—and the result was a lot of fun. You can listen to our work at these links: ‘Thought Crime‘ and ‘Sun of Water, Sea of Light.’

Laurence: I had just started digitizing my master tapes—previously unreleased material from my various bands and solo projects—when the pandemic hit. Mixing and releasing nearly 30 CDs on my label through Bandcamp kept me busy at home in creative isolation. The following bands of mine are now well represented on Bandcamp: The Empty Set, Larynx Zillion’s Novelty Shop, Velveteen Blue, Gordon Gigantic, My Biography, as well as a lot of solo collections. Here are some links to my Bandcamp pages:

Laurence Bond Miller

Velveteen Blue

Larynx Zillion’s Novelty Shop

For the sake of accuracy, let’s begin at the very beginning. What was it like growing up in a household with all brothers interested in music in the 1950s and 1960s?

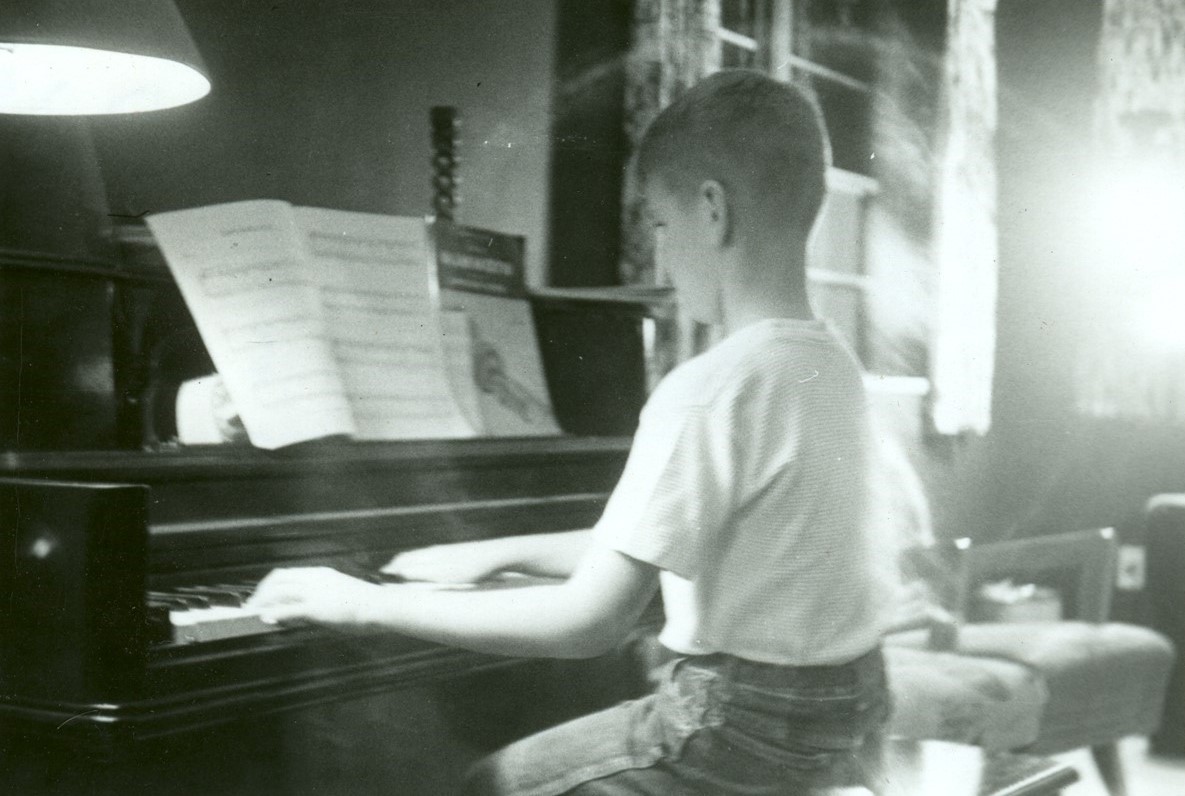

Roger: Our dad played piano when we were kids, and there was always classical music on the turntable, along with the usual musicals like Oklahoma! and My Fair Lady. Falling asleep to César Franck, Mozart, or even ‘The Rite of Spring’ was kind of magical as a kid—it felt like a journey into dreams.

Our sister Frances, eight years older than me, and our brother Gifford, six years older than me, were from a slightly different musical generation at first. Giff was into the folk scene, so we listened to Peter, Paul and Mary, and early Dylan before the Beatles hit. I found that music interesting, but not life-changing. I started playing piano at age six, and Laurence did too. Benjamin started on saxophone in 4th grade, and Laurence played clarinet (if I remember correctly). I kept playing piano and started learning French horn in 7th grade. That was the fall of 1964 for me. Music was always a part of our lives. My sister enjoyed playing piano and accompanied me when I performed a Mozart French horn concerto at a festival in southeastern Michigan in 9th grade—I even got a blue ribbon! My first “accompanying gig” was in 6th grade for the Wines Elementary School band, which was performing the hymn “Abide with Me.” They needed help, and I was the most well-known piano player in the school. So I learned the piece and played with the band. I suspect my comparatively accurate notes made the more random pitches seem to make sense. At any rate, that was my first public performance.

When the Beatles hit in 6th grade (1964), everything changed. Like so many others in America, I was a completely different person after seeing them on The Ed Sullivan Show for the first time. Before that, I was just a kid doing regular stuff; afterward, I was a rocker. Hell, I still play rock music—I’m 72 now, and I was 12 back then. That’s 60 years and counting. The day before they appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show, our dad brought home ‘Meet the Beatles!’ He had heard from students that it was going to be “the next big thing.” I didn’t quite get it when he played it as we were going to sleep. But after seeing them on TV the next night, I went out and bought the album the following day. From then on, I was hooked.

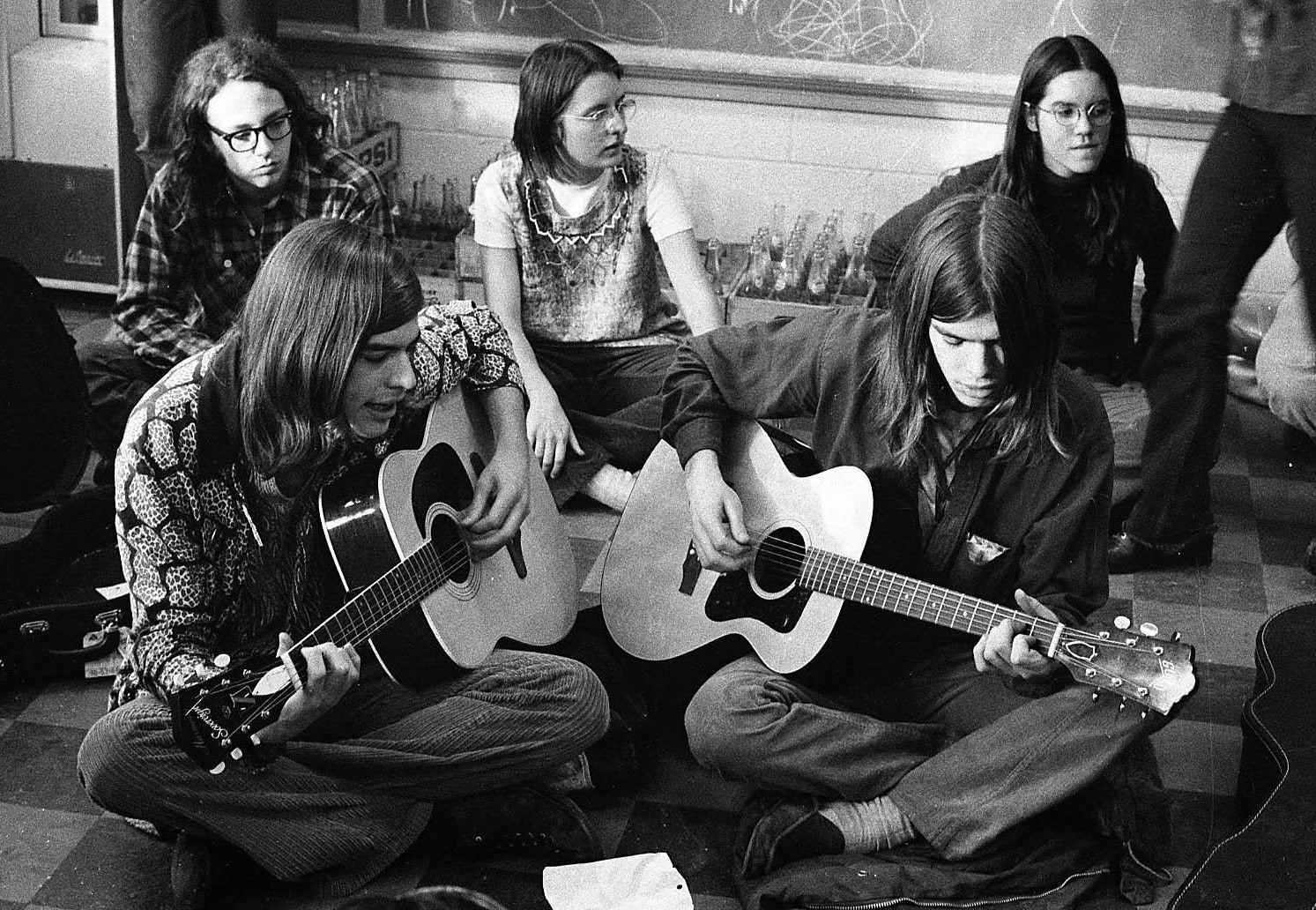

Music was always a part of our family life. When we played in our school orchestras or bands, our family would come to our concerts, and afterward, we’d have root beer floats. When I bought a cheap Silvertone acoustic guitar in 7th grade, all three of us—Laurence, Benjamin, and I—learned on it. Lar and Ben had friends who would come over and play too, so there were always about five or six guitarists around. It felt like a class, with everyone teaching each other.

I remember in 7th grade, my mom still made me take piano lessons, which annoyed me because all I wanted to do was rock out. However, my teacher gave me Béla Bartók’s ‘Piano Music for Children,’ which sparked my love for Bartók. So, in 7th grade, I was taking piano lessons (which I’m now grateful for), learning French horn at school, and practicing guitar at home with my brothers. Dad was still playing classical music in the evenings, and we were starting to pick up guitar licks from the earliest Rolling Stones records. It was a fertile environment.

Ben: I was very fortunate to have two brothers who were as into music as I was. We had so much to share with each other, from listening to records to playing together. Even our oldest brother, Gifford, who became a scientist instead of a musician, listened to a lot of music—The Four Seasons, Peter, Paul & Mary, The Beach Boys, and Bob Dylan. Our sister Frances, who was studying primates in Africa for her master’s degree, even sent us music from Africa—curious pop songs on 45 rpm records.

Laurence: It’s safe to say that we three were moved by music from early childhood—it was in our blood. But our fascination didn’t fully bloom until 1964, with the Beatles and the British Invasion. Our oldest brother, Gifford, and our sister, Frances, were more interested in folk music, but they weren’t as keen on making music as we were. Our dad played classical records regularly on the family phonograph in the living room, and he and Frances also played the piano. Dad often took us to orchestral concerts at Ann Arbor’s Hill Auditorium over the years.

Tell us what your parents did for a living.

Roger: Dad was a Professor of Ichthyology, specializing in fish, at the University of Michigan. It was interesting for us as kids because every summer, we would travel to the western U.S. deserts to collect fish and dig for their fossil ancestors. His job involved comparing the two and trying to understand evolution. I thought this was normal, but around 11th grade, I realized most kids didn’t spend their summers in the desert, seining for fish in mountain creeks and desert springs, then sleeping under the stars on tarps. Perhaps these experiences have influenced our approach to music.

Mom attended college, but later became the dedicated professor’s wife. Raising five kids was quite a task, but she still found time to help Dad with his research, noting air temperatures while collecting fish, organizing expeditions, and doing other supportive tasks. I’m amazed at how she handled it all. Her mom, my grandmother, also supported her husband, who was an ichthyologist too. It seems history does repeat itself.

Ben: Our father was a paleo-ichthyologist, and our mother worked closely with him on everything, just as her parents, Carl and Laura Hubbs, had done. As a family, we spent our summers in remote areas of the southwestern United States and Mexico, collecting live and fossilized fish specimens for one or two months. This definitely influenced our perspective on nature, which you can hear referenced in many Sproton Layer songs, as well as in other projects and our paintings.

Laurence: Our father was a paleo-ichthyologist, serving as curator of fishes at the Natural History Museum in Ann Arbor. He was fascinated with native fish species in Mexico and the American Southwest, whether fossilized or alive. In terms of life lessons, both he and our mother taught us perseverance and patience in documenting information, focusing on the details of what was important. Our dad was a field scientist at heart, and our mother supported him every step of the way.

Was your father’s background in music a factor in sparking your interest in the field?

Roger: As mentioned, besides sometimes playing Beethoven and Chopin on the piano, his consistent playing of a variety of classical music and musicals made music an enveloping environment growing up. We didn’t think about it; it was just there. Besides the usual classical stuff, he liked the Romantic period and had Stravinsky’s ‘Firebird Suite’ in rotation. He even had a Carter ‘Cello Sonata’ album, though I don’t recall him playing it. When he heard our interest in certain expanded psychedelic rock music (think ‘Saucerful of Secrets,’ ‘Sgt. Pepper’s’), he suggested we go to the University of Michigan music school’s “Contemporary Directions” concerts, where they played the latest “classical” innovations. So in the afternoon, we’d see the MC5 at a free concert in a park, then in the evening go to one of these free concerts at the U of M and listen to Penderecki, Stockhausen, or Terry Riley. It was a pretty good deal overall.

In our house, studying music was part of growing up. That aspect was from Dad, not Mom. Mom once told me music was not a valid career – but studying fish was! Later, Mom became more supportive once she realized I was never going to be a biologist.

Later, Mom and Dad came to see Mission of Burma play in Ann Arbor. Mom said, “I couldn’t understand the music, but you and Clint had great stage presence!” Dad (without Mom) later came to see Birdsongs of the Mesozoic play. He loved that we did a sequence from “The Rite of Spring,” and I think he loved that I continued playing piano, which he had to abandon to become an ichthyologist. Definitely the oldest person in the club!

Ben: Dad listened to music a lot; the Classical masters, Bartók, Stravinsky, Villa-Lobos. I recall a lot of Chopin and Saint-Saëns, who I still listen to fairly regularly. He bought us “Meet the Beatles” when it came out. Huge impact. Most assuredly, he was a positive force, not to mention his DNA. I tried to turn him onto Erik Satie, but he was not taken by it. However, when I bought him a CD of Philip Glass, he was smitten.

Laurence: Yes, our father wanted to be a professional musician as a youngster. He won a silver medal in a recital at the age of 16. The medal was on our living room mantel, remaining there our whole life. We were impressed, especially as we grew to further understand what that must have meant to him. He loved music, particularly Romantic classical; Chopin, Rachmaninoff, Beethoven, and Tchaikovsky—but also Stravinsky and other modern composers. As stated earlier, our father played these records on the living room phonograph regularly, and this sank in.

We were also influenced by his sense of random humor in the way he played with words and goofed about at home, singing silly stuff out loud, and so forth. He had a free, spontaneous expression about his nature, one without standard cause or rational reason, per se. As a family, we saw movies together at Ann Arbor’s Cinema Guild. The Marx Brothers films were my favorite—hilarious romps which would later align our expression as the musical Miller Bros., rebelling against and giving the finger to the presumed establishment and all its artistic, aesthetic “norms.”

Was there a certain moment when you knew that you wanted to become a musician? What was the scene like in Ann Arbor, Michigan, back in the ’60s? Did you see a lot of shows?

Roger: Certain Moments When I Knew I Wanted to Be a Musician:

Moment No. 1: 1964: The Beatles on Ed Sullivan. Actually, it took a couple of weeks to sink in. This continued from 1964 through 1970.

Moment No. 2: 1971: After Sproton Layer went nowhere (fall 1970) and I gave up on being a musician, I was attending the University of Michigan as a liberal arts major. While “studying,” I realized that what I was actually interested in was playing guitar and piano. Well then, fuck everything else. I have stayed on that road ever since.

The Ann Arbor Scene:

There were two threads for me:

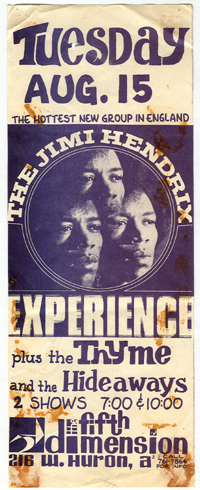

The 5th Dimension:

In 10th grade, I was in art class, and someone there suggested I do posters for the Ann Arbor club The 5th Dimension. So I learned this squiggly psychedelic lettering technique and made posters with tempera paint on construction paper for weekend shows. The posters hung in the outside window, and for this, I could get into the club—which was only a mile away from my parents’ house where I lived—for free! Wow! My parents would only allow me to go once a week, but that got me going. Walking into the foyer with the black light posters, then rounding the corner into the main room, felt like home to me. It was magical. I saw the local bands there for free: SRC, Amboy Dukes, the Rationals, etc. For the bigger shows, like Hendrix (first US tour), Pink Floyd (Saucerful tour), Mothers of Invention, I had to pay because a different promoter booked the club. But that was what lawn cutting, leaf raking, and snow shoveling were for.

The Free Concerts in the Park (Love-Ins):

The first free concert in Ann Arbor at West Park was during the “Summer of Love,” 1967. The Grateful Dead headlined, with the Charles Lloyd Quintet and the Seventh Seal (featuring Bill Kirchen) opening. Literally half a mile down the street from my parents’ house, this was my new reality. This continued until the concerts were moved to Gallup Park (further out of town) in 1970, I think. I had to bike to that one. The MC5 doing “Starship” with Rob Tyner, eyes upturned in his head, rushing through the audience while all three guitar headstocks were rammed into their amps, feeding back with Machine-Gun Thompson laying down an interstellar beat, blew my 9th (or was it 10th?) grade mind. Commander Cody was perfect for calming me down from an edgy acid trip. This was life, just like The 5th Dimension.

Ann Arbor was a hotbed for revolution and expanded consciousness applied to music for three or four years. As mentioned above, seeing the MC5 in the afternoon and then Stockhausen/Penderecki at night pretty much summed up my attitude.

Ben: Although I hadn’t composed or written a song yet, by the time I was 14, I began to assume I must be a guitarist. I had been playing since I was 12 and alto saxophone since I was 10. Being a musician seemed to be where I was heading. I had wanted to play alto saxophone ever since 1st Grade. The Ann Arbor music scene was great in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Sproton Layer auditioned for booking agents, but we were just too young.

I saw Pink Floyd at The 5th Dimension with Roger in 1968. They were pushing ‘Saucerful of Secrets.’ It was a major letdown for me. I expected the high energy and diversity of ‘Piper.’ There was no light show, and the music was all laid-back. We saw lots of shows at the West Park Love-Ins and later at Gallup Park: The MC5, The Up, Third Power. I almost saw SRC at the Union Ballroom. They took so long setting up that we had to walk home in time for dinner. In 1971, I started seeing shows in Detroit—Pink Floyd, Alice Cooper, Captain Beefheart, The Kinks.

Laurence: I was touched by music at a very early age. Then, sometime in elementary school, I was exposed to bagpipe music and was blown away. Sadly, yet understandably, my mother claimed bagpipes were very expensive and very difficult to learn. I began piano lessons in 3rd grade, and someone gave me a Scott Joplin Ragtime book for Christmas. I found it to be a lot of fun, but my piano teacher had no interest in “teaching in that style.” Teachers, of course, can do a lot for or against one’s early interests. I also began to learn how to play the clarinet in school in 5th grade and took lessons soon thereafter. But the British Invasion soon became a reality and with it, center stage in my life. I knew with no uncertain terms I was to be a musician. I taught myself how to play guitar (left-handed but strung right-handed), and from there, how to play drums with The Freak Trio and writing songs.

I was fairly introverted in my youth and consequently did not gravitate toward large crowds. I was still underage, and though there were venues promoting all-ages concerts, I just rarely went. I regret that now, I suppose—missing Jimi Hendrix and Pink Floyd in Ann Arbor, if you can believe that. Seeing the MC5 and The Up, along with other local bands in West Park on a regular basis (just a few blocks away from home!), was good enough for me.

But I found myself having a bit of trouble in my teen years, as many kids do, I suppose. I had new friends, new music, and was figuring out how to glue it all together. Teen angst, but watching a good deal of it from a distance. This may be partly why I later reinvented myself as a children’s performer? It seems I always had an inner child the size of Texas. But all that aside, we three brothers were absolutely drawn to original music, and the local rock scene of the late 1960s fueled that. Mainstream Top 40 radio quickly became a thing of the past, and it’s been that way ever since.

Did you have a certain hangout place where you listened to the new records and just hung around with your friends?

Roger: Our parents’ house, where we lived, was the congregation site. One of our rooms had a console stereo. Friends would bring over their albums, and we had some, too. So, between all of us, we heard most of the good stuff from 1964 to 1970 when it came out. I had other friends where high school sleepovers happened, and we’d get stoned and listen to the Velvet Underground’s first album, ‘Their Satanic Majesties Request,’ and ‘Magical Mystery Tour,’ that sort of thing. I recall one friend laying me down with the left stereo speaker at my left ear and the right at my right ear. He swore that if you listened to the first 13th Floor Elevators album that way, you could hear a third guitarist in the middle of your head. He was correct. They had three guitarists, despite what the record label said!

Ben: Yes, in Roger’s bedroom (mono) and the living room (stereo).

Laurence: Nope. Home in the living room or in Roger’s bedroom, where three of us would often “toke up” in the early days. Roger (being our older brother by two years—it made a difference then) turned us on to new music, as did all our friends.

“The MC5 were beyond fantastic”

The MC5, John Sinclair, and the White Panthers, the Stooges… tell us how it was to experience all that?

Roger: I was a little too young to be directly involved, but it sure was exciting. I saw the MC5 10-15 times? They played free shows regularly. I saw the Stooges twice: their album release show in summer 1969 at the Eastown Theater in Detroit, where they were a totally tight rock band with Iggy’s astounding dancing as a focal point. I saw them again late in 1969 playing a benefit, and this time it was a wall of feedback and Iggy threatening everyone in the front three rows. No songs. Great stuff! The next day in high school, everyone either thought it was the worst thing they’d ever seen, or else amazing. I was of the latter opinion. One of those shows.

In 1971, I had a girlfriend who was more political than I was, and we attended some meetings at Hill Street House (Panthers/MC5), but it was a mixed bag. Eventually, the White Panthers became The Rainbow People’s Party, and you could tell it was getting watered down. Eventually, it became the Rainbow Corporation! But they did lots of good stuff until it dissipated somewhere in the mid-’70s (I think).

Ben: The MC5 were beyond fantastic. They would often open their sets by tuning their guitars at top volume. The energy was always positive, unlike The Stooges. I saw Iggy & The Stooges once at the Forsythe Junior High School cafeteria, of all places. It was terribly loud and disorganized. Iggy was a drag. As for The White Panthers, I was not politically active at the time, other than an anti-Vietnam march here and there, so that part of the Ann Arbor/Detroit movement didn’t phase me much. I really wasn’t involved.

Laurence: As exciting as it all was, I was young and consequently the whole thing was a bit overwhelming at times. West Park and Gallup Park were the places I saw most local bands, with the MC5 being my favorite. They kicked out the jams—big time.

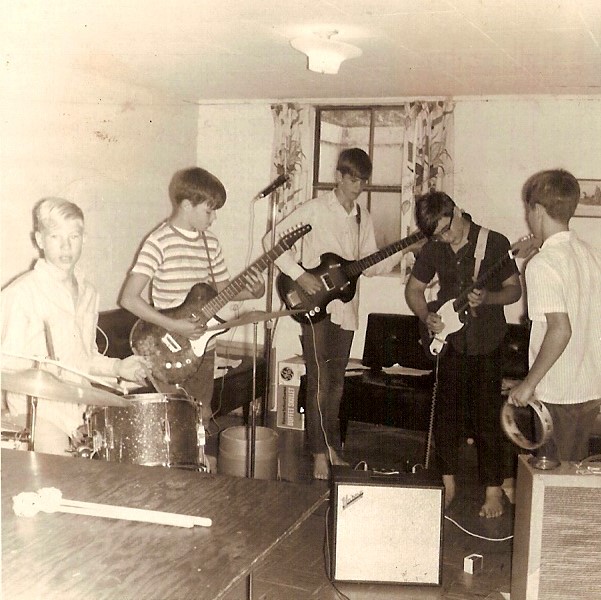

I would love to hear a bit more about your very first band, which was called The Sky High Purple Band. You were very young at the time. What kind of music did you want to play? Did you do any shows?

Roger: The band existed “something like” from May 1967 into fall 1967 (memory and all that). For some reason, none of my friends played guitar, but Lar and Ben (2 years younger than me) had friends who did. When I saw all the guitarists that had gathered in our house, just playing fragments of songs, my organizational skills kicked in, and I wrangled us into a band. Tom Grimes was the best guitarist, so he played lead. Dave Rodgers was on drums. Ben played rhythm guitar, Lar played tambourine and generally backing vocals, and, because no one else did it, I bought a bass and became the bass player and lead vocalist. While I definitely organized the group, the material was made up of the music we all loved: the typical Kinks, Stones, and Animals, but also 13th Floor Elevators, Love, Hendrix, West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band, Yardbirds, Jefferson Airplane. We tried to learn ‘Help I’m a Rock’ by the Mothers of Invention, but it was beyond our skillset. None of us were writing real original material at the time, so we were a snapshot of the beginnings of psychedelia. I was just going into 10th grade, everyone else was going into 8th grade. None of us had “directly partaken” of psychedelics yet, but it was in the air. We played two shows that summer: one in a friend’s garage and another in a friend’s attic. Two guitars and a lead vocal mic into one little Univox amp if I recall correctly, and I had a pretty bad Lectrolab bass amp. But we played those two shows and likely didn’t suck. Before my voice changed, I could cop a pretty good Grace Slick on “White Rabbit” and “Somebody to Love.”

Ben: We played at our friend Matt Becker’s attic. I was very nervous. It was 1968, I think. We played a mix of garage rock and psychedelic rock cover tunes. The highlight for me was the last song, where I put the guitar neck between two wooden poles and bashed it back and forth. A girl was coming up the stairs at that time. She looked horrified.

Laurence: I was the harmony singer, playing tambourine, maracas, and harmonica. I believe it was Gene Clark from The Byrds I was emulating. I did write a simple blues tune for the band called ‘Look Out Pretty Mamma.’ Not much to it and as naive as it gets, but hey, I was just 13. Later, I purchased a used mandolin and fell in love with the double-string sound. I believe I suggested bringing that into the band’s sound, and that was… well, perhaps not such a good idea.

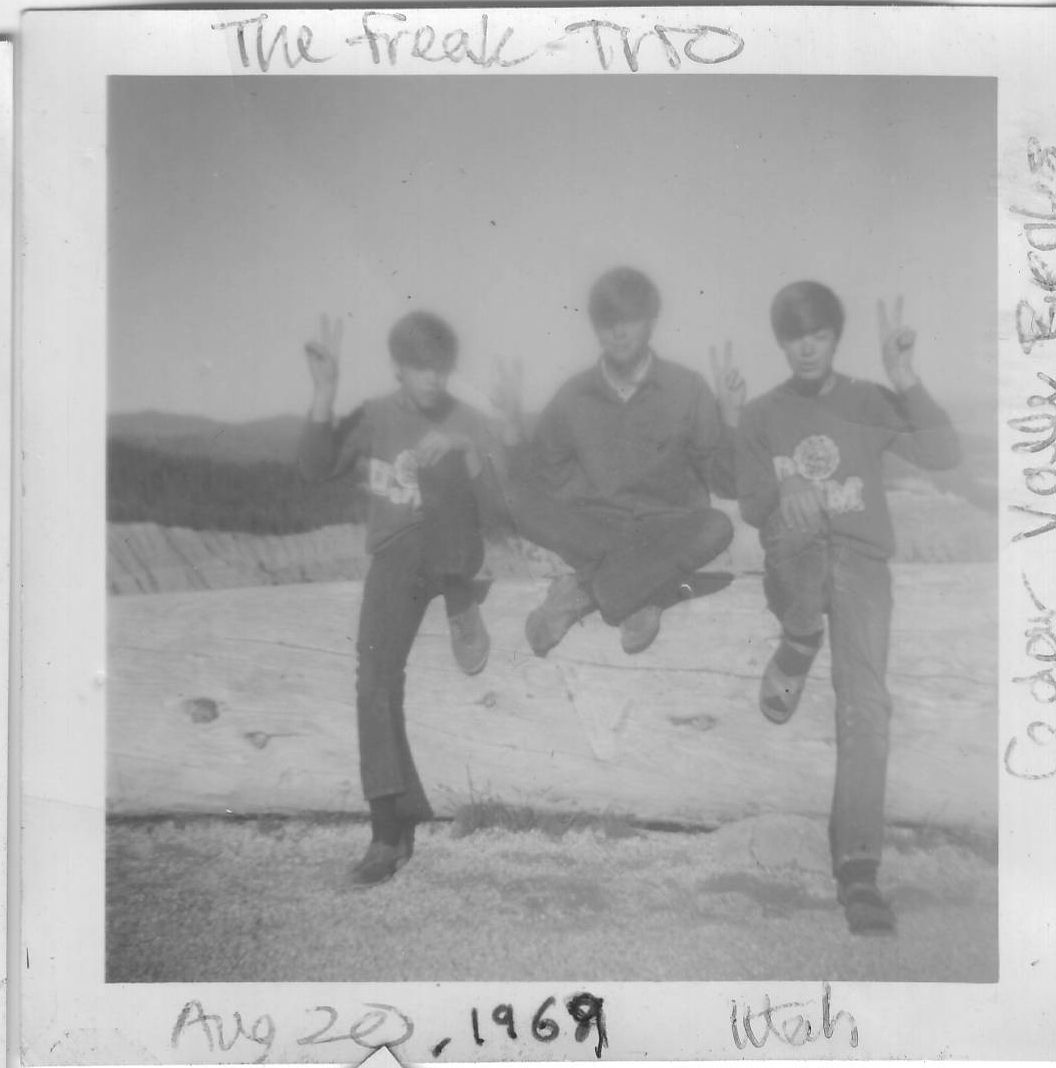

“Roger’s was a peace sign, mine was a mushroom, and Ben’s was a star”

What about bands like Mandrake Fields, Factory, and Freak Trio? What kind of material did you play? Are there any recordings, released or even unreleased, of it?

Laurence: I’ll let Roger handle Mandrake Fields and Factory since I was not in those bands. The Freak Trio was born out of a life-changing event, jamming in the basement one evening while our parents were gone square dancing on a Friday night. We had been developing rich inner lives as three brothers, ever since Halloween 1968, when we were high while carving pumpkins, and upon finishing our designs, found that each of us had inscribed a symbol on the back. Roger’s was a peace sign, mine was a mushroom, and Ben’s was a star. These became our magic symbols as such, and from that point on, we were The Freak Trio.

We developed and shared a rich inner creative life based on multiple stoned adventures over the next year. Roger developed concepts inspired by Greek mythology and created The Toke God—a ceramic piece made in art class—as the ultimate Creative Spirit we worshipped. A ritualistic gesture made by emptying the pipe’s ashes into its bowl in sacred gesture, giving our all due respect, was mandatory. All our creative activity was done solely under the influence of marijuana. We believed it had the power to open our minds to new ways of perception, thus new music—and in some ways, it most assuredly did!

Our stoned adventures together gathered more and more steam, with The Broccoli Birds becoming a real concern—originating from Roger’s “Fruit Books,” written a couple of years before. They had come out of the books into our cosmic battles, and this was our new life. One of our kites (in real life, as they say) got caught in the telephone wires in our backyard and remained there for months. We knew it as a dead broccoli bird. That kind of thing. Rabbits were apparently on our side during various imaginary battles, so no worries there. They were actually helpful. And then there was The Mechanical Rat, our arch enemy, of course. I think the rabbits scared that thing off by our using the “Freak Sign” (two fingers spread wide like rabbit ears, or so our memories indicate), defending us against The Mechanical Rat. Yup. Needless to say, we collectively shared a rich inner world that first year.

I too began writing acoustic guitar songs sometime later in 1968. These were simple, imaginative pieces usually lasting less than a minute in length, as I didn’t believe in repetition, nor did I have any understanding of how to develop ideas. Again, we rarely did anything unless we were high, as we sincerely believed there was a magical element waiting to show up in that experience every time. Consequently, and in some ways, one might argue, this could have been a deterrent.

At only 14 years old, my focus in songwriting was primarily on the fantastical. Nothing political or “girl-meets-boy” or anything standard. True, I had found myself smitten with a girl in my class at school, but I was too shy to do anything about it. However, the songs I wrote were quirky—sometimes upbeat, sometimes frightening, and sometimes just playfully thrown together in an offhand, stoned manner. I had no plans regarding a musical career other than simply recording my own songs for posterity, continuing through 1972. Song titles such as ‘I’ve Walked Long,’ ‘The King’s Display Holiday,’ ‘On My Hill,’ ‘The Emblem Man,’ ‘The Ozone Came Alive,’ ‘Galavan,’ ‘The Orms of Yale,’ ‘Cumble Snare,’ and ‘The Death Concerto,’ to name a few.

Roger: Mandrake Fields was the first band I was in during High School, after Sky High folded, from late 1967 through early 1969. I mean, what 10th grader wants to play in a band with Junior High School kids? So Sky High was over, definitely due to some of that stupid mentality. Mandrake Fields was a blues band, and I was merely the bass player. We covered Paul Butterfield, John Mayall, James Brown, etc. I’m still friends with the leader, Steve Dreyfuss. I mostly smoked weed and played the songs they chose, but it upped the ante slightly. We played at our High School and at parties. These guys were older than me.

I got frustrated with the band, though, especially with the Cream/Hendrix thing coming on strong, and formed Factory in early 1969 or late 1968. That was the first band where I wrote original material, basically second or third-tier Cream/Hendrix. But likely not that bad for an 11th grader. We played a couple of shows at Jr. High dances. During this period, I came up with the (eventually Sproton Layer) song ‘In the Sun,’ which was NOT typical Cream music: dissonant and hypnotic, more like the Silver Apples than Cream. The other guys in Factory just couldn’t figure out what to play, and I knew that this was the direction I wanted to go. Frustrated again. And so…

A month later (March 1969), Lar and Ben and I recorded an improvised session on Factory’s gear in the basement of our house; this was the Freak Trio Electric session, and that changed everything. We were so pumped by this session. This was no longer blues-based jamming; instead, anything could happen at any time. It was totally liberating. I called a meeting a day or two later, and we formed a band pronto. I wrote “Gift” and “Sister Regis” in short order, and Lar immediately got the right beat for “In the Sun,” whereas Factory could not. I kept Factory rehearsing just enough so that we could use their gear and get Sproton Layer in action (at that time called Freak Trio: Three freaked-out brothers). When the other guys in Factory eventually realized what I was doing, they took their gear back, and Freak Trio/Sproton Layer folded for a couple of months until we could find a new gear-sharing situation.

Ben: I can only speak for Freak Trio. It was a crude version of Sproton Layer without a trumpet. The band meant a lot to me, though. The music was all original, and we felt this was of utmost importance. As brothers, we had been “space-jamming”—a freestyle form of improvisation off the top of our heads—for a while. We were spurred on to form as an actual band after Roger, Laurence, and I did one of these “space jams” in the basement of our parent’s house in the Spring of 1969. We were ecstatic about this new-found creative trajectory using amplifiers and a drum set.

So this leads us to Sproton Layer? How did you choose the name, and what initiated this project?

Ben: Roger would have a better answer for this. Essentially, it was a more professional version of Freak Trio with the addition of a fourth member. I was hoping for a musician who could play the organ, much like our early inspirations with Pink Floyd, Procol Harum, Soft Machine, SRC, etc. That said, having a trumpet player was very cool. One curious note is that our oldest brother, Gifford, was amusingly confused about the end of the verse for the song ‘Gift.’ The line was “It’s a gift,” but Gifford thought Roger sang, “It’s Giff.”

Laurence: Again, Roger could best follow up on this. As I understand, the concept behind the name was the idea of setting two or more layers of a particular type of marijuana in a pipe. That was, and I quote, a “sproton layer.”

The Freak Trio wanted a fourth member—ideally, a keyboard player. So many bands that inspired us (like Syd’s Pink Floyd, SRC, Procol Harum, etc.) had keyboard players, and both Roger and I had been brought up taking piano lessons. We were also influenced and moved by classical piano music our father played regularly on the living room phonograph. That said, as fate would have it, Harold Kirchen was added to the mix as a trumpet player in the band!

Roger: We were so inspired by Freak Trio Electric, it’s hard to explain. It was no longer blues jamming—it was closer to ‘Interstellar Overdrive.’ From that point on, ‘Piper at the Gates of Dawn’ became our ideal. Even my child-like fantasy songs—like ‘Bush,’ ‘Sister Regis,’ etc.—were similar to Syd’s work, though I wasn’t imitating him; I was just being myself. The first Soft Machine album and the first Silver Apples album were also extremely influential, along with the first SRC album (from Ann Arbor). Once F.T. Electric happened, the new road opened right up. The three brothers had an intuition that other players I found just did not. We had all studied, to some degree, classical or orchestral music as kids, and we all went to Contemporary Directions New Music Concerts, as well as seeing the MC5. So we were fine with sounding more like Stockhausen than Eric Clapton.

When the band reformed in late fall 1969, our good friend (and stoned adventure sharer/causer) Harold Kirchen was added on trumpet (his brother is Bill Kirchen, from Commander Cody and earlier The Seventh Seal). At that point, it was no longer just Freak Trio—three brothers. So we needed a new name. We had the habit of drawing while listening to music, and I looked at one of my drawings and saw the phrase “Sproton Layer” written there. It seemed like a good name, so we used it. It made no normal sense, much like the way normal/straight “magnetic fields” are disrupted by weed.

Tell us about the Freak Trio Electric in March 1969.

Roger: As mentioned, we had all of Factory’s gear from my current band in the basement. We borrowed a tape recorder from a neighbor. Who knows why we decided to toke up and improvise to tape while our parents were out square-dancing? But we did, and the results blew all of our minds. Riffs and motifs appeared out of nowhere, sometimes in complete unison. I was so energized by this that I incorporated a bunch of themes from the session into songs that I shortly wrote: ‘Strange Lands,’ ‘Lost Behind Words,’ ‘Tidal Wave.’ It was literally a seismic shift, and I went from writing Cream knock-offs to songs that were the real me. I had just turned 17, and Lar and Ben were close to 15. It was pretty noisy and chaotic, and definitely was NOT a Cream-like blues jam. It was something else entirely. I immediately wanted to end the straight-forward Factory and start a new band with my brothers. They were into it, so off we went!

Ben: This was the aforementioned space jam that spurred us to form as an actual band: Freak Trio. We were blown away by the spontaneity of the music and the off-kilter changes that the improvisations morphed in and out of. It reminded us of the magic embedded in Pink Floyd’s “Interstellar Overdrive.” The instruments were not aligned with formal positions. The bass guitar could suddenly take on a melodic riff, the guitar could do a jagged cluster without concern for tonal center, and the drums didn’t need to do backbeats. We were unaware of Free Jazz at the time, and thus this was more like Free Rock. The experience literally turned our heads around and influenced our musical directions until this day.

Laurence: It wasn’t until March 1969, with our Freak Trio Electric recording, that we became an actual rock band. That was the key turning point in all our lives as musicians looking forward. This spontaneous combustion event could clearly be compared in movement to Syd’s ‘Interstellar Overdrive’—and no surprise there. Transforming ideas, shifting quickly from one to the next, in a raw unfolding succession. Unusual musical segments spun as free association, so to speak. Upon playback, it was discovered that “the sound of the ozone” had indeed been captured, and yes, that was that! Though it was recorded on a cheap tape player (set on top of the dryer at the other side of the recreation room), the essence was retained! We were sold!

[Note: I never had guitar lessons partly due to the fact that I played upside down, having learned to form chords upside down on my brother’s right-handed acoustic guitar. And that said, I never had drum lessons either. In fact, I had never planned on being a drummer. The night of Freak Trio Electric, I simply sat down at the drum set, which of course was set up right-handed. It never occurred to me. It wasn’t until 20 years later in Six Minutes to Think, Ben’s band, that I decided to try combining two sets together to create an ambidextrous arrangement, as the best of both worlds.]

Roger, being two years older than us—a significant gap at that age—quickly took on the role of band leader and chief songwriter. This was good, as someone needed to take the reins. Around June of that year, we had to take a break. Factory (the band Roger had been in) took their gear back out of the basement, and our mother was freaking out after discovering her three young boys were smoking dope. Thus, it all came to a temporary halt.

Roger and I then formed an acoustic duo over the summer of 1969, with both of us contributing as songwriters. ‘Calling You with Horns in My Mouth’ was one of Roger’s that I remember particularly liking. ‘The Ozone Came Alive’ was one of my tunes we worked on. The Freak Trio, as a band, thankfully bounced back in the fall of 1969, soon followed by the addition of Harold Kirchen on trumpet before the year was up, and with that, SPROTON LAYER was born!

Note: ‘The Chorp God’ was my one and only song written specifically for Sproton Layer. That was probably written near the end of 1969—an absolutely undeveloped idea with no common sense in form. I didn’t blame my brothers for the thumbs down after just one rehearsal. Interestingly, there’s a scribbly spot on the original paperwork where, in the spirit of John Cage I suppose, it is suggested to place a transparent music staff over it to determine which notes to play.

You did a lot of experiments with your sound, and the result probably stunned you, as it made a lot of sense when hearing it.

Roger: Yes, and when we listened back to the tape, there was this background hum when the music stopped—it was the cheap-ass compressor on the tape recorder mic ramping up room ambience. We called it “the sound of the Ozone!” We were, as I said, just teenagers rather pepped by the whole thing.

During a previous improv session from Jan. 1, 1969, I was using a plastic bag to create sound effects. We just went with whatever was around—all three of us. Always.

Ben: Very early on, we could 100% identify with the unusual as a foundation to work from. It was what we were drawn to. I believe it was partly due to the scientific DNA we got from our parents—the desire to explore and discover. As guitar effects pedals became more diversified in the ’70s, experimentation continued. Laurence’s band, Empool, is a good example of that, which also included pre-recorded backdrops on tape recorders.

Laurence: Roger had the brilliant idea of inserting areas of our recorded improvisations into his songwriting—moments where the three of us had gelled particularly well. Another example of this kind of thing, for instance, was a moment during a recorded acoustic jam session. We three had chanted “Easter Eggs” until the phonetic sound morphed into what sounded like “Sister Regis!” Roger later worked that in as the title of a lovely pop tune of his about the sister of the Wizard King of Tokes! All that made good creative sense to us!

Would you mind taking your time and sharing some further words about the material that was released under the name of ‘With Magnetic Fields Disrupted’ and ‘Lost Behind Words’?

Roger: I wrote down the phrase ‘With Magnetic Fields Disrupted’ in Spring 1969, with an image of magnets (with their fields disrupted and not disrupted), and this reflected my feeling for what weed did. When you were straight, the magnetic fields were normal, so you had typical chord progressions and song topics. But when you smoked weed, the magnetic fields were disrupted, and things came out strange and non-normal. Heh, that was us.

Disrupted” (1972) | Photo Jim Rees

‘With Magnetic Fields Disrupted’ was recorded by Mark Brahce, and I conceived it as a complete album. Which, eventually, it came to be.

Most of the songs are from the earliest period, Spring 1969. ‘Gift,’ ‘Pretty Pictures Now,’ ‘Sister Regis,’ ‘In the Sun,’ ‘Tidal Wave,’ and ‘Up.’ ‘Bush’ and ‘Nocturnal Mission’ were a little later but similar in that they were on the mythical side.

When we reformed in the fall, my composing had developed more. ‘The Blessing of the Dawn Source,’ ‘New Air,’ ‘Point of View,’ ‘The Wonderful Rise’ were all written from December to Spring 1970. I later referred to these as the “symphonic” type of material. More elaborately structured, less fairy-tale-like. Though even the “fairy tale” types often had a darker side, much like Barrett’s writing. For example, ‘Tidal Wave,’ besides being mythic, is really about a double death (the king was already dead, and his mourners were about to be obliterated by a tidal wave). Why was a 17-year-old writing something like that? Who knows…

Ben: Most of the material performed by Freak Trio and Sproton Layer was written by Roger. However, the first part of’ ‘Tidal Wave’ was a conglomerate of ideas taken from our space-jam recording Freak Trio Electric. The last section of ‘The Blessing of a Dawn Source’ is a chord progression I came up with. ‘Point of View’ and the beginning section of ‘New Air’ was greatly influenced by the 20th Century concerts we were attending at Ann Arbor Michigan’s Contemporary Directions series. I am particularly proud of my guitar solo on ‘New Air.’ At the time, I didn’t know any other guitarist approaching a guitar solo like that, other than Syd or Jimi.

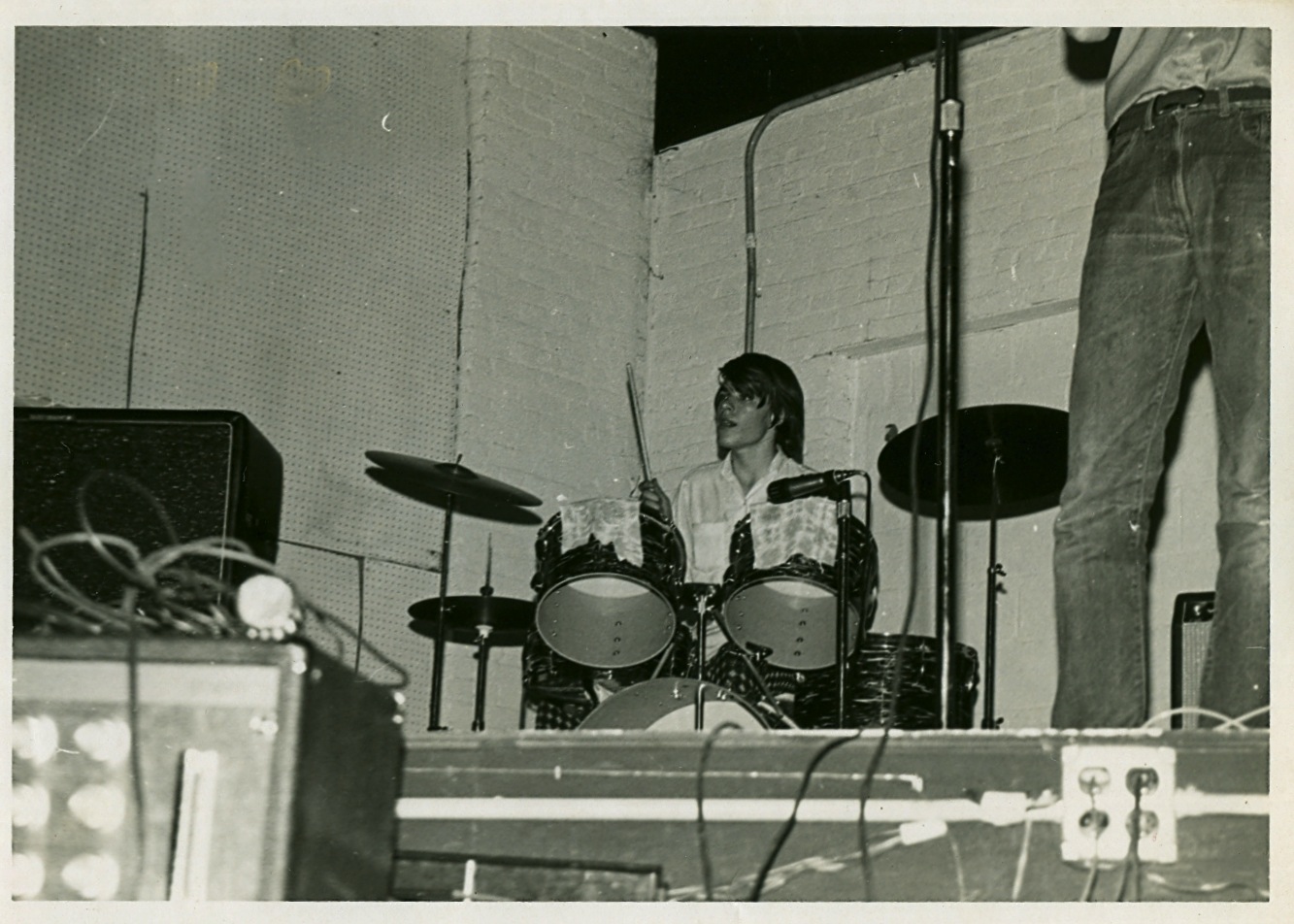

Laurence: I didn’t know how to write rock music, so I never wrote in that context. My favorite songs of Roger’s were ‘Point of View,’ ‘New Air,’ ‘Up,’ ‘Sister Regis,’ and ‘Lost Behind a Word.’ But I don’t have much more to add outside of sharing my influences as a drummer: Ginger Baker, Keith Moon, Nick Mason, Drumbo, Art Tripp, Neil Smith, and symphonic orchestral percussive styling as a whole. Albeit, my chops were limited because I had zero practice discipline and no teacher to help me navigate. I was just in the habit of padding down my drum heads with rags as a poor boy’s way to deaden the sound. Ringing bothered me, partly due to the fact that I didn’t know how to tune drums! My double-rack-tom Yamaha kit was, in fact, a piece of crap, but it was all we could afford. [Note: I became a far better drummer later in life. Recordings with Larynx Zillion’s Novelty Shop, Six Minutes to Think, and Exploded View are prime examples of my later talents if you ever get the chance to listen closely to those collections.]

I believe that most of the material was recorded in 1970 in a really basic DIY recording setup. Would love to know more about that. Who was Mark Brahce?

Roger: Mark Brahce was in my class (1970) at Pioneer High School. He and I tied for the most poems in the yearbook that year (6 each, though I had 2 drawings as well)! We often discussed music together. He loved Sproton Layer and took it upon himself to learn how to record a band. He did a test run in December 1969—’Lost Behind Words’ is from that session—which was a bit harsh. But he did it. He put blankets up on the walls of our basement and ran a few mics into a mixer, premixed to one channel. Then, overdubbed the vocals via “Sound on Sound” while bouncing the music to the other track. So the result was mono and couldn’t be remixed. He improved his gear and technical prowess considerably by August 1970 when we recorded ‘With Magnetic Fields Disrupted.’ Really, if Mark hadn’t decided to learn how to record us, none of this would have been documented like this. After Sproton Layer, he did a bit more work with me, then went on with his life and never recorded anybody else. I am still friends with him, of course. What a curious sequence of fate.

Ben: Mark was a good friend of ours. We didn’t hang out much, but he very much enjoyed Sproton Layer, and thank God he was willing to record us at that time. The basement walls were mostly cinder blocks, with one side being wood. So we hung sheets and blankets over the cinder blocks where our mother would normally hang clothes to dry on a white rubber wire. The floor was linoleum. He used one mic on the Acoustic 150 transistor guitar amp and one mic on the Ovation transistor bass amp. These were early transistor amps that had a weird “crunch” to them. They were advertised as the next best thing because the amps turned on instantly instead of the common tube amps, where you’d have to wait a few seconds. And there were no problems with tubes burning out. Little did we know! I don’t know how Mark mic’d the drums. The vocals were overdubbed. No vocal booth! The piano overdub was a cheap upright in the upstairs living room. I don’t think there were any guitar overdubs.

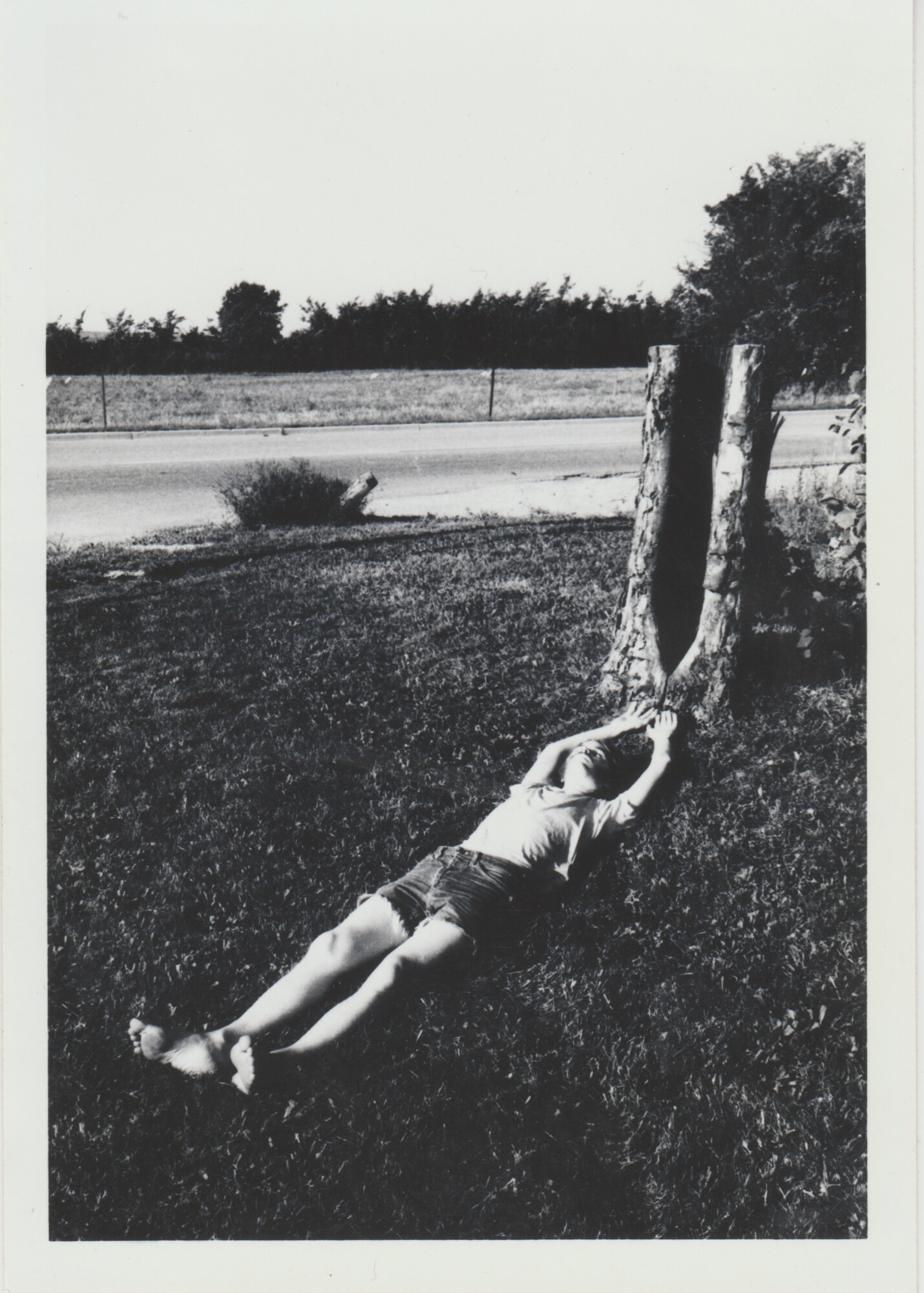

Laurence: It was a very basic stereo reel-to-reel analog recording setup in our family’s basement, where we had practiced and jammed from the beginning. We did our best to deaden the cinder block walls by draping blankets over the clothesline. The soft asbestos ceiling tile wasn’t so bad, I suppose. Roger and Ben did vocal overdubs, and Roger even added piano on one piece. I was just thankful we were recording it all, relaxing in the backyard between songs.

It must have been quite frustrating that no label picked up your music, as it was very original. Did you at least get any reply from the local press or so?

Roger: I dropped off a tape to the Rainbow Party HQ on Hill Street and got no response. At that point (18, just out of high school), I didn’t realize that you had to keep pestering people to get their attention. Plus, psychedelia was fading, and we were psychedelic. Basically, when the recording got no response, I was pretty devastated. Here we were, a fully formed band of pretty high-quality musicians, and I (mostly) had written a full album that made sense from start to finish. It was my magnum opus of two years. Nothing. Crickets. Until Gertrude Kurath later picked up on it (see below).

Ben: It was very depressing. The lack of interest in the tape caused the band to fold in a matter of a few weeks.

Laurence: Yes, it was absolutely disheartening not to be encouraged further in our own home town. We felt we had something truly special to offer from the beginning. I honestly don’t recall the logistics, as Roger handled all band business. He probably did a good job at it, too. The whole idea of a “music entertainment industry model” completely eluded me.

You played several shows between April 1969 and August 1970. What are some of the most memorable ones, and what are some bands you shared stages with?

Roger: Playing with Carnal Kitchen—who I loved—on the University of Michigan campus was a highlight. They were a free-improv group that featured Steve Mackay, who later played on the Stooges’ ‘Fun House’ album. One of our last shows was with Commander Cody and the Lost Planet Airmen, because Harold’s brother Bill played in the band, and they were being good to us. Ben borrowed Bill’s Twin Reverb amp for the show, and, according to Bill, Ben’s more aggressive tone and use of the Fuzz Face ruined the Twin Reverb’s clean sound. I think he had to buy a new one!

My favorite show was in January 1970, where we played a party at a hippie frat house. Everyone was sitting on the floor, smoking dope. We played two sets of original material, then improvised the entire third set. It was the ideal kind of show for us. Otherwise, we didn’t share stages with other bands much. We were kids and hadn’t broken into any scene. And never did.

Ben: We played at several friends’ parties. I recall one in Ann Arbor on Oxford Street. After two sets of songs, we did our designated set of space jams. At the end of that set, we decided to repeat our song “Yellow Balloon,” only in reverse. We did, in fact, do just that, stunned that it was executed with precision! Unfortunately, the recording is lost. We also played at the Big Steel Ballroom, opening for Commander Cody and his Lost Planet Airmen. That was perhaps our most professional concert. I don’t recall what the audience thought, but Bill Kirchen, brother of Harold, claimed his Super Reverb guitar amp (which I had borrowed for the gig) never sounded the same again.

Laurence: Opening up for Carnal Kitchen in 1969 was exhilarating. I’ll never forget watching a college woman in the crowd, sitting cross-legged on the floor in front, bobbing her head enthusiastically to our song ‘Up.’ She had truly tapped in, and that’s all we ever really wanted from our audience.

On another note, no pun intended, it should probably be noted that I had developed a romantic obsession with a girl in school at this time, much like I had with another the previous year. It became a slow-burn bloom where I was soon completely preoccupied. I’ve since learned I had a psychological condition described as “Limerence.” Flights of fancy and depression developed. On occasion, I caused scenes with friends, drinking heavily. I soon met with a psychiatrist and from there was committed to Mercywood, a small Catholic-run institution on the outskirts of Ann Arbor. During my one-month stay in March 1970, Roger talked our parents into convincing my doctor to let me out for a gig at our High School. I wasn’t happy about it and was, in fact, surprised such a thing could be done. All I recall from the show was playing three songs and having a tough time keeping tempo due to the heavy medication I was on. I continued with psychiatry after being released, for the remaining year of 1970, doing my best to stay clean. It was later learned in the mid-1980s that our father had a bipolar mood disorder. I was then later diagnosed with the same in 1991 after getting sober. Today, I may simply have what they call a hyperthymic temperament.

Back to “most memorable” shows, I really enjoyed the one in April 1970, performing in our Pioneer High School’s “Little Theater.2 We were well received by our peers, and I felt particularly strong as a performer for the first time. Later that summer, we performed a solid show at Ann Arbor’s Big Steel Ballroom, where we opened for Commander Cody and the Lost Planet Airmen. It all felt a bit odd playing such psychedelic rock alongside a popular mainstream country-twang band, however. Their guitarist—the amazing Bill Kirchen—was in fact our trumpet player’s brother, hence how we got the gig. As a side note, we brothers had heard Bill Kirchen’s band, The Seventh Seal, perform at West Park a few years earlier. That group ran far closer to the psych-rock sounds we pushed in Sproton Layer. Time changes everything.

Things began to fracture between us brothers shortly after my first hospitalization. It was probably just that we began to change, as teenagers do, grasping for our own identities and hopes and dreams, etc. School and life in general soon pulled me back down again. By November 1970, I asked if I could return to Mercywood. I spent another month hospitalized there, then was released shortly before Christmas. It was decided a change in scenery might help me, so arrangements were made to live with my oldest brother Gifford and his future wife in Nederland, Colorado. I finished my 11th grade there, which I found helpful and refreshing, moving back home by June 1971.

As for Sproton Layer, the last time I remember toying with the idea was at the end of that year. We three recorded a few improvisation sessions. It was a bit naive to dive back in on drums, though, since I was not proficient and never practiced on my own. We did play for a friend’s wedding celebration as an ‘instrumental band,’ and that was that. Bill Gracie (a local drummer around our age) happened to be attending and became the drummer as the wedding party progressed. This was fine, as I had begun to tie one on anyway, and he was far more accomplished than I.

In 1972, Roger and Ben formed a band called Cerberus, with Bill Gracie now on drums. They were an amazing psych-rock band, actually. Bill was not only extremely talented but also perfect for the material my brothers were writing. Though not quite as radical-sounding as Sproton Layer, they were essentially a continuation of the idea. I think in a perfect world, as with Sproton Layer, Cerberus should have been signed immediately to a studio to record a full LP of their original music.

Was there any other band from the same circuit that didn’t get proper exposure that you were aware of back then?

Roger: Probably. Carnal Kitchen! Free jazz wasn’t exactly a big seller at that point.

Ben: Probably.

In our interview, you mentioned that you got back together in 1971 and formed an all-instrumental band that produced some interesting “space jams.” Under which name was that?

Roger: It was still called Sproton Layer, but I’d sold my PA system by then. We recorded a few improvisation sessions (one mic in our basement) and played at a friend’s wedding in this context. No vocals, more groove than our previous sometimes odd start/stop compositions. It’s basically free improvisation applied to rock music. Some of the improvs are really good. I will be happy if they get released (it’s currently “possible”) and see if anyone else is as excited about them as I am.

Ben: We still called it Sproton Layer, I think, and rehearsed four or five instrumentals that were unfortunately never recorded. ‘Speedway’ and ‘Acid Jungle’ were two I wrote. ‘Acid Jungle’ was recorded by Exploded View with Laurence and myself in 2015—retitled as ‘Triton.’ This second incarnation of Sproton Layer performed at a couple of parties. The late Bill Gracie asked to play drums after we did a set, and out of that experience, Cerberus was born. My songwriting had improved by then (1972), but unfortunately, the two that I wrote, ‘An Hour of Days’ and ‘Put Away on Pluto,’ were never recorded.

What’s the story behind Gertrude Kurath? I was fascinated by that in our previous interview.

Ben: Roger would know.

Roger: THAT is indeed an interesting story. Fall 1970. I felt Sproton Layer was a total failure, and I was pretty unmoored. Gertrude Kurath (in her 70s) had gotten a Wenner-Gren Foundation grant to write two books about mixing the Church and popular music. Book One was on folk liturgy, and she wanted to write a second book on rock music and liturgy. Doing research, she wanted to understand devices like wah-wahs and fuzz-tones. She contacted a friend of mine, Bruce Fulton, on this topic, and he referred her to me. I was pretty low-key about it and gave her a copy of ‘With Magnetic Fields Disrupted’ (WMFD), where we used both a Fuzz Face and a wah-wah pedal, and I thought that would give her an idea of their use.

I dropped the tape off to her, and about an hour later, I got a phone call where she was nearly sputtering because she was so excited by the music! She said she had changed her plans and now wanted the second book to be the entire score written out for ‘With Magnetic Fields Disrupted.’ “Songs of Death and Rebirth” is how she described it.

I was rather surprised by this development but said, “Sure, I can do that.”

So over the next year, I wrote out the entire scores on score paper—drums, guitar, bass, trumpet, vocals—by listening to the tapes. I wrote a blurb for each piece—12, just like the album—and an opening bit. She wrote the real opening. I got paid $200.00 for doing the typing. Whoopie! But, in a peculiar way, Sproton Layer finally got some attention.

The book did come out, and you could order the tape too, which I took to a guy who did tape duplication in Ann Arbor. He added reverb to it because he said, “that’s how it’s done.” So, that was how it was done. There was an article in the Ann Arbor News when it came out in fall 1972. I considered it an anomaly, but still, a 70-year-old woman was the first person to realize that WMFD was a special thing. Crazy. She had been a dancer in the Martha Graham era, so she had art in her blood.

I never got a penny in royalties, and neither did Gertrude. I kept in touch with her for some time, playing tapes for her, whatever I was currently doing, about once a year. Hell, she was one of the few people who actually listened!

Did you ever obtain a copy of the book and the tape?

Ben: Yes.

Roger: I have the master tape, of course. And a few copies of the book remain in our possession. The Ann Arbor Public Library had a copy until I checked in the early ’80s, and it was gone.

“Weed and this music were completely connected”

Did you often experiment with psychedelics, and do you think it opened some new musical doors for you?

Roger: Well, it was the ’60s, so of course. Weed and music: F.T. Electric and other “space jam”/improvisations on weed were magical. So weed and this music were completely connected, like it was for many at the time. We totally believed weed was the key. I wrote a number of songs (like ‘Sister Regis’) about ‘The Toke Mythology’ that I more or less made up. It was somewhere between Alice in Wonderland, Dr. Strange, and The Wizard of Oz. LSD was also interesting: The song ‘Lost Behind Words’ came about because I was tripping and couldn’t talk very well. I closed my eyes and had an image of a shadow of a person behind a large 3D image, very ‘Yellow Submarine,’ of the word “Word. ‘Lost Behind Words,’ yes. I consider psychedelics to be like dreaming in real time. I now think that, while psychedelics definitely opened up Western culture, it was not the actual “key”—something else is that!

Ben: Cannabis and psychedelics were part of that time period, yes. It did seem to open up the creative outlook regarding music and the arts. Open improvisation (Space Jams as we called it) and out-of-the-box songwriting that went far beyond the “boy meets girl” humdrum approach of Top 40 music at that time was key. The Beatles had figured that one out by the time ‘Revolver’ was released. Listening to that LP and many others at that time (1966-70) was a huge inspiration. It helped those doors to open!

Laurence: Yes, and yes. When I moved back home from Colorado in the summer of 1971, I formed an acoustic guitar duo with Ben. We called ourselves Brainal Unit. One might argue it was a cross between Tyrannosaurus Rex (not Marc Bolan’s metal rock) and Simon & Garfunkel. I soon began smoking dope and dropping LSD again, and my songwriting quickly took off into outer realms. We performed locally and in school several times over the next year. It should be noted that the psychedelic experience for us Miller brothers wasn’t like going to the movies, as it was for some friends we knew. Trips tended to be profound, and some of mine were indeed bad. Existential views rapidly grew for me, but with continued deep understanding and values held toward the natural world—a connection we were all brought up to believe in as a family when we were kids growing up. I’d tripped a few times in 1969/70, but most of my major psychedelia flew between 1971 and 1973. These experiences absolutely fueled freer songwriting structures and further abstracted concepts in group improvisation. Performance Art (as it would later be called) began to creep into my intentions as well. I continued psychedelic exploration through 1975, but only with micro-dosing.

In 1975, you attended a small art school. Tell us how that came about?

Roger: I had hit a dead-end in Ann Arbor and was looking for something different to do. A friend suggested this “open/free school (college)” in the middle of Michigan, so I attended Thomas Jefferson College in Summer 1974. It was one of the best moves I ever made. It got me out of my stoned Ann Arbor rut. Lar and Ben came out that fall. The composer/teacher Denman Maroney, who has recorded some of his unique prepared piano work, which he calls ‘Hyper Piano,’ joined the faculty that fall. He looked at my interests and suggested I research Surrealism. That was an eye-opener for me. And he took us to a series of concerts in NYC (my first time there) celebrating the 100th anniversary of Charles Ives. Hearing Edgard Varèse and Ruth Crawford Seeger in a live setting was mind-opening. He turned us on to John Cage, really liked my composing, and encouraged me to keep it up. He was a major influence on my life. I delved into Carl Jung then too, which turned out to be quite interesting. It was a seismic shift.

Ben: Laurence and I had spent 1973-74 in music school in Boston and were not happy with our experience. A friend of ours, Julian Catford, suggested we attend Thomas Jefferson College—an art school just north of Grand Rapids, MI, that also offered music classes. Roger agreed we all attend TJC and form a new band with original material.

Laurence: Ben and I were still schooling in Boston from 1973 to 1974, and we’d become disillusioned with the whole music school thing. Our friend Julian Catford told us about this art/music college he was attending in Michigan called Thomas Jefferson College. Roger, having been particularly moved by an improvisation with us while visiting Boston in spring 1974, approached us then—probably in a written letter—with the whole idea of joining creative forces once more as a Miller Bros. Band in college together. We all talked about it, and it was decided Ben and I would move back in the fall of 1974 and enroll.

Ben and I began fleshing out new ideas, as well as developing compositions we’d written in Boston. We had high hopes to find a drummer and get things going with Roger. Jack Waterstone had been Roger’s roommate earlier that summer, if I’m not mistaken, and so we all began jamming together, building band chemistry. By 1975, we found a drummer, but he didn’t last, leaving us in final form as a four-piece band.

What led to The Fourth World Quartet, with school-mate Jack Waterstone rounding out the quartet?

Roger: Lar, Ben, and I were trying to get an ensemble going that fall. I had written an “opera” called ‘War Bolts’ for reed pump organ (me), bass clarinet (Lar), and electric guitar (Ben). It had vocals and was written because I was initially let down by Eno’s ‘Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy)’—I thought that record would be much more involved in storytelling, and I took it upon myself to make that correction! I later completely changed my mind about Eno’s record, of course, and it is definitely his masterpiece. But the acoustic setup we had didn’t work for the composition. I’m not sure exactly how we finally decided upon the piano/bass clarinet/alto sax/electric guitar lineup with Jack Waterstone on second alto sax, but once we did (late winter/early spring 1975), we went all in on it, and Fourth World Quartet became a living entity. Jack had been my roommate at T.J.C. that summer, and we were all studying with Denman Maroney. It was the most natural ensemble for us at that time.

Ben: Compositions that Laurence and I wrote in Boston were at first the focus of that band. He and I also wrote fresh material. Roger brought in some music he had written previously, and Jack Waterstone happily joined forces as a third horn player. Roger quit directly after the “1975” recording and returned to Ann Arbor. The Fourth World Quartet continued with TJC music teacher Denman Maroney until that summer when he was offered a teaching position with a reduced salary.

Would you share your insight on the albums’ tracks that Cuneiform Records recently issued? Where did you have those recordings stored? What studio did you record in?

Roger: Our friend Rick Scott (later in Birdsongs of the Mesozoic), also at T.J.C., was a fan of the band and had acquired a Braun tape recorder (later used by Martin Swope for tape loops in Mission of Burma). He had a pair of good mics, so we absconded to the orchestra room of the school system there, and he recorded the band live, with me on a Steinway grand piano. Given the semi-accidental nature of this, it came out really well. Much like ‘With Magnetic Fields Disrupted’—if Mark Brahce and Rick Scott hadn’t stepped up to the plate, there would basically have been no real recordings. My favorite moment in the recording session is as follows: We were doing Jack Waterstone’s improv-based piece “Ambrosia Triangle,” and I was playing percussion. I used whatever was there: timpani, cymbals, snare drums, etc. Of course, we were scruffy hippy-looking guys and hadn’t asked permission. Suddenly, in the middle of ripping into ‘Ambrosia Triangle,’ the school’s musical director opened the door and looked in. And, of course, we had not asked permission. So we finished the recording, and, as often happens in my life, it fell to me to talk to the guy. So I walked over and explained that we were working on a Stravinsky piece (we were—it’s on the album), and I presented us in the most “upstanding” way I could muster. For some reason, he bought into it, even though he walked in while the horns were free-form wailing away and I was hammering the timpani. So… we kept on recording! And the album ‘1975’ is the result.