Peter Wrenleau (Wale) | Diaries: Unveiling the U.S. Chapter: ‘For the Record 1’

‘For the Record 1’ encapsulates Peter’s journey of resilience and determination, from his aspiring songwriter days to the release of his transformative album.

Despite facing setbacks and challenges, the album stands as a tangible testament to his artistic vision and enduring spirit. Through its melodies, Peter seeks to reignite a sense of optimism lost over decades of struggle.

Tracks ‘Take Down The Old Flag,’ ‘Going From My Mind,’ and ‘Groaning Up Free’ were recorded live at the Mini Mall in Cortland, NY on July 14, 1976, capturing the raw energy of Peter’s performances. Meanwhile, tracks ‘This War’ and ‘Narcissus’ were meticulously crafted at Bear Creek Studio in Woodville, WA, circa 1979, showcasing his evolution as an artist. The album’s seamless flow and fantastic sound quality are attributed to Adam Selzer’s signal restoration and mastering at Type Foundry.

The jacket artwork, a visual counterpart to the album’s evocative soundscapes, was skillfully designed by Rachel Christenson. Each cover of the limited album is handprinted and unique, adding an extra layer of artistry to the musical experience. For enthusiasts eager to own a piece of this musical legacy, inquiries about purchasing can be directed to rachelchristenson@yahoo.com.

Limited to just 50 copies of the hand-finished version, ‘For the Record’ is a rare gem that promises to captivate listeners and collectors alike.

Peter and Rachel have decided to continue Peter’s biography, starting from where the previous one left off in our interview from 2019 (see here). The release of ‘For the Record 1’ is nicely accompanied by the next chapter of their story.

Diaries: Unveiling the U.S. Chapter

First Things First: An Old Flame

Feb. 4, 1974. I arrive in Miami airport as the travel guest of a farming family from Missouri whom I met in Cali, Colombia. The first thing that I notice is how offhand and rude the airport staff are. It’s my first introduction to the not-so-nice side of America. The family members are Charles and Levinna Kirksey and their children, Tommy, Missy and Jennifer. We all get into a large sedan of theirs and head north toward their home in Risco. They assure me that I can get hired on the spot as a picker in the citrus-growing area of central Florida. I need money and think it a good idea. They drop me in Haines City at a motel which costs $10/night. The next day, I land a spot with a picker crew headed by a tall, black man with huge hands by the name of Tobe Evans.

From Feb. to Apr., ‘74. Tobe is nice to work with. Besides picking, he also directs the crew and drives the tractor that picks up full wire bins, while delivering empty ones. He is curious about having a young white guy from Africa on the team and stops to chat every now and then. He gives me tips on how to pick more efficiently and sometimes even gives me a hand. His hands are so large, he can hold eight oranges in one of them. The work is brutally hard, especially since I’m still not fully recovered from a bout with hepatitis A that I caught in Cuzco, the year before. We are paid $3.10 for each bin that weigh around 600 lbs. when full. The oranges are picked into a long canvas bag that hangs over one’s shoulder. When full, this bag weighs around 90 lbs. You pick retreating from the top down. Trees must be picked clean. I am unable to make more than $40/day, but manage to save money.

The motel I’m staying in is very well kept up. One night, one of the most violent electrical storms descends on the area. Inside my safe, comfortable room, I revel in the sound and the spectacular light show. I like being there but decide to move to a cheaper residential hotel in downtown Haines City. This ultimately proves to be counterproductive when a thief breaks into my room and steals all my money, along with a pack of semi-precious stones I had brought safely with me all through South America from Brazil. I must now start all over from scratch. The extra time spent in downtown Haines City introduces me to some pretty dangerous young white men – weapons-carrying, professed rapists, thieves, drug sellers, gangsters and ex-incarcerated convicts. Fortunately, the story of my journey impresses them and they let me be. I’m respectful, but I keep my guard up. Ultimately, the citrus season ends. I have enough for paying the Kirkseys back for the airfare they insisted on lending me for the flight from Barranquilla to Miami, plus a fair chunk for the hitch-hiking journey, northwest across America, toward my goal: Vancouver, British Columbia.

Apr. and May ’74. As an experienced hitchhiker, because the money I have is limited, my best option for reaching Seattle with enough cash to pay for cheap lodgings is to stand on the side of the highway and use my thumb. To make my intentions clear to drivers, I use the case of my guitar as a sign board. Using white chalk, I write “Seattle” in big letters on it. Getting a ride out of Florida is pretty slow going. Not having an atlas to guide me, I have to trust that those who give me a ride will be helpful. My first destination is Birmingham, Alabama, the family home town of a young woman – Caryl A. – I had met and really fallen for back when she was a student in Cape Town. It doesn’t take long to get there. Though it has been three years since I last saw her, I am no less smitten than before. This time, however, she has a serious love interest to whom she will soon be engaged. Inwardly, I am crushed, but I gamely play the rôle of guest while she plays that of faultless host. The visit is sweet and all too brief. Two days later, I say goodbye and get back on the road to resume my journey, this time headed to reconnect with the Kirksey family in southern Missouri, so I can pay them back. When I get there, I am welcomed and Charles gives me a tour of the farm. It’s early spring, so nothing is growing. I meet a young woman through the Kirkseys who takes me under her wing. One thing leads to another and she takes me home. It’s a just a one-night stand, but much needed, after a long time without intimacy. The next day, Levinna Kirksey gives me a ride to the nearest highway and the journey resumes.

I don’t recall much about the ensuing journey other than passing by Springfield, Missouri, and crossing the Mississippi River at Kansas City in somebody’s car. I don’t check into any hotels, motels. I doze off in whatever car I happen to be in. I vaguely remember passing by Topeka. Just outside a town called, Colby, Kansas, my luck with rides runs out. I stand by the road for a day and a half without anyone stopping – so much for the people of Kansas, one of America’s most conservative states, today. Eventually, a young man from Denver, Colorado, headed in that direction, picks me up. I tell him about this girl named Deanna Baker I had first written to when we were on the yacht, sailing from Cape Town to Rio de Janeiro. I had come across her picture in a Playboy magazine. She was the drop-dead, perfect body centerfold and she worked at the Denver Playboy club. I mailed the letter when we got to Rio and she had replied. When we get into Denver, he suggests we go to the club to see if we can find her. She isn’t there, but the folks at the club call her and she invites us over to her home. When we get there, I discover that she has a live-in boyfriend (not surprising, but still somewhat disappointing). She isn’t quite as gorgeous and angelic as the photo spread had made her out to be, but nonetheless, attractive enough, in a big-boned kind of way. Despite my being a stranger, they are welcoming and hospitable, and invite us to have dinner with them. Everything is congenial, but after dinner a joint is passed around and it makes everyone (especially me) too doped up to keep the higher vibe going. I’m a real dullard on weed. We leave the place with me feeling somewhat deflated and return to the Denver home of my ride-giver – an anti-climactic end to a two-year period of anticipation.

The next morning my host receives an emergency phone call from his sister, whose car has broken down in Burns, Oregon. She needs a ride back to Denver and is being housed by the pastor of a church over there. My host and his brother say they will come and fetch her, trading places at the wheel. Knowing that my ultimate objective is Seattle, they ask me if I want to go with them. This is a huge opportunity. It will take me significantly closer to where I want to go (1,600 miles, I have since found out). We set out immediately, first north, to Cheyenne, Wyoming, then west toward Logan, in Utah. I remember how bleak the landscape looked as we crossed the Continental Divide, 7,000 feet above sea level. Sometime early next morning, we cross into southern Idaho, and then, northwest to the freeway along the great curve of the Snake River. In the late afternoon, we pass a mile south of Boise. It looks beguilingly green, with big trees. Two hours later, as night falls, we reach Oregon, going past Vale, westward on the long, lonely, two-lane highway toward our destination of Burns and the home of the pastor Crim and his family. We reach there late that night and are warmly welcomed.

The next morning, after a wonderful, resuscitating breakfast, the Crims arrange for me to get a ride up to Richland, Washington, in a van with a team of high school tennis players to which their daughter belongs. I bid goodbye to my Colorado friends/benefactors. The ride they gave me remains the longest I have ever caught. The girls in the van are as beautiful a travel group as I have ever had the opportunity to share a vehicle with – all in short white dresses, and obviously very fit, but I don’t recall any of them speaking to me. As we drive north on Highway 395, we pass through Long Creek, past the town café, which is where I sit and write, today, in front of the wood stove, in that same building. I don’t even notice. Exactly 40 years later, Rachel and I will walk through the door as that café’s new owners/occupants. The tennis bus drops me off in Richland and, dependent on asking strangers to help with directions, I end up on a narrow road, just outside the nuclear research complex at Hanford that no one seems to be using. After a couple of anxious hours, a fellow working at the facility drives up and asks me where I am headed. When I say, Seattle, he tells me that it is his day off and that is where he is headed. Only later do I realize what a stroke of luck this ride is.

I have never been in Washington state before. As we head toward Seattle, 14,410-foot, Mount Rainier, looms up over the horizon. It towers like an awesome white monster among the lower peaks around it. When we pass over Snoqualmie Pass, snow is piled high on each side of the road. Three hours after leaving Hanford, my ride-giver wishes me luck and drops me off on the main street of Capitol Hill, in Seattle. The only tall structures in the city are the 600-ft. Space Needle – built for the World’s Fair in 1962 – a not very tall black building, the Seafirst Tower, which disgruntled locals sardonically refer to as the box the Space Needle came in, and the Smith Tower – at one time, the tallest building west of the Mississippi. The city’s modest skyline gives it a warm, open feeling, welcoming to a newcomer like me, but that feeling will be steadily lost to development over the four decades that follow. Thus is completed my 3,100-mile, cross-country hitch-hiking trek from the SE of America to the NW.

Now I must look up a young woman of Japanese extraction named Margie Konma, whose name I was given by Alistair Winter, a colleague of mine at the English language school in Cali, Colombia. Thanks to my association with Alistair, she agrees to give me a place to land while I seek my independent accommodations. Though cordial, she is cool toward me. It doesn’t take me more than a couple of days to get a room at a residential hotel on the corner of 1st Avenue and Pike Street, smack dab in the heart of downtown, owned by a Chinese couple. The name of the establishment is the Elliott Hotel. A portion of the northwest ground floor of the building is occupied by a donut shop that does a brisk business with those who frequent the corner, which is infamous for drug deals, prostitution and occasional instances of violence. Bad as it may be, it is still better than what I encountered in Haines City, Florida. Over the ensuing three months, I have no problems entering and leaving the Elliott Hotel. My weekly rent is just $13. It’s across from the Pike Place Market, where foods can be bought. The kerosene stove I brought with me through South America proves useful for quick preparation of vegetables, pasta, instant rice and top ramen. I have to stretch out my money until I can start earning again when the apple-picking season in Michigan kicks off in September.

In the meantime, I am totally focused on reconnecting with Dawn Armstrong, with whom I had lived in Johannesburg and Cape Town. She had left suddenly, with no reason given, leaving me devastated and no less in love with her. Why else would I have traveled so far, on a shoestring, to be able to see her again, despite knowing that the chances of getting back together again were close to nil? At the first opportunity, I travel up to Vancouver to see her. I arrive in the early evening at a house in central Vancouver. Meeting her again, after a separation of three years, is awkward. Even in that short time, the inner glow and pep I remember her emanating is gone. Instead, there is a new, disturbing dullness about her demeanor. Nothing is rekindled because there is nothing left inside to catch alight. But I keep hoping.

My return back to Seattle goes without a hitch. I meet Terry Clayton in the University District. He is a big man with a warm heart and many friends and has a house just to the west of the freeway. His girlfriend is Paula Arnal – a beautiful, slim-figured, earnest woman, a little older than I. I like her and we will remain friends for years until something strange happens that is neither my fault, nor hers. It is at Terry Clayton’s that I meet a very attractive and very intelligent, young, married woman, called Susan McTighe. It is lust at first sight. She is a law graduate with big ambitions, a good heart and a hidden libidinous side. To her, I amount to little more than a curiosity, a toy to be collected – something which l only fully comprehend later, but cannot condemn, given that my own approach to life is pretty similar to hers. In this case, however, my own interest is not quite so basic as hers. I really like her. Nevertheless, I am under no illusions about prospects of any kind. She visits me at the Elliott Hotel, basically for sex, and little besides, and I know it. I really have nothing else to offer. It will not be the only experience of this nature, as the years in America unfold.

June and July, ’74. Somehow, I am introduced to a family by the last name of McGowan. They need someone to paint their second house on Whidbey Island with a product called Woodlife. Later, it will be banned because it is carcinogenic. I need to earn some money and I take on the project while staying in the house. The product has a foul chemical smell and is very unpleasant to put on, but I complete the job. The patriarch of the family, Howard, is famous for having been a major mover for the construction of a complex of dams on the Columbia and Snake Rivers. The giant project creates abundant hydroelectric energy, but decimates salmon runs forever. While I am there, they and guests engage in what they call the Flounder Round-up by wading out into the shallows and corralling flounders into a tight circle of closed legs. It’s a game only. The flounders are set free for the next year’s event.

Back at the Elliott Hotel, I become friends with a Korean immigrant by the name of Kim Chon Woo. His company is a comfort. Being so long alone and far from anything I can think of as home and without detectable future prospects, combined with the slow diminution of my meager funds and the realization that my connection to Dawn is a sad vestige of the fiercely romantic companionship we once shared, pushes me into a persistent state of gradually increasing depression. It culminates in an out-of-body experience while I lie on my bed, in which my consciousness rushes down a tunnel from which I do not attempt to escape. Abruptly, the tunnel ends and I emerge onto a field of effulgent green. I move across the field towards where three gentle hills come together. There is a pool there with absolutely clear water. I become aware of someone standing by the water’s edge, off to my left, and turn to look. It is a woman in an orange sari. Her features are south Asian. I ask her “What is this place?” She says a name. I will know it immediately after I emerge from this state, but forget it in the years ahead. A vague guess seems to suggest the sound, Elliukaal, but I can’t be sure. I drift off across the field of green, adventuring further. Things morph into a vibrating realm of vividly changing colors, shapes and sounds. The experience becomes somewhat frightening and when it does, I am suddenly yanked back into my body, but somehow, unable to make it do anything. I succeed in sitting up, but quickly realize that my physical body is still lying flat. It dawns on me that I need to reintegrate mind and body, so I lie back down into the physical aspect of myself and concentrate on connecting everything back together. It takes will and a little time, but works as intended. It becomes, at once, my first subjective experience of the multi-dimensional structure that makes an earthly incarnation possible. It is also my last crippling depression experience, suggesting that those who claim that clinically dangerous depression tendencies can be alleviated by psychotropic substances that induce an altered state of being, combined with meditation and guidance, may be right.

I make one more trip up to see Dawn in Vancouver. She has moved with her friend, Cherrie, to a nicer house in Burnaby. The visit is brief and uneventful. Soon I am headed back down to Seattle. This time the American border police are not so accepting. I am taken aside and questioned. I have nothing to hide and answer every question forthrightly. He asks me in a friendly way, “Have you ever considered living in the United States?” Thinking that he is asking me what I think of the country, I say, “I’m not really sure, but maybe.” Of course, I don’t realize that this is a trick question to ferret out my unspoken intentions, regarding potential residency in the United States. Actually, I have no intention of overstaying my visa allowance. My desire is to get to London, where I might fit in more easily, and where I might have better success with the music I write. Truth be told, I feel pretty out-of-place in America, culturally speaking, and not likely to find any rôle in it that would provide both security and a sense of belonging for me, but that’s too complicated an answer for a border guard to have to peruse. He immediately suspends my right to re-enter and tells me I have to appear before a circuit court judge before I can re-enter. Christ! All my stuff, including my precious Yamaha FG 180 guitar and my money is sitting in that room in the Elliott Hotel. I now have to go back to the Canadian border people and ask for an extension. They give me three days, but the hearing with the circuit court judge is more than a month away. I’m fucked. I return to Dawn’s place and, because I have no other option, impose myself on their graces. She lets me call Susan McTighe. Maybe, with her legal experience, she can help. She comes up to Vancouver with her sister, Mary Jo. She has a plan. There’s another way to get back: by commuter plane. I don’t have the money with me, but she does, and I have my passport, complete with the permission of my visa to be in the US. We will leave together the day after tomorrow. I have no alternative but to give it a try. This time, if I’m asked the same question, I’ll just say, “No.”

Meanwhile, all the ladies decide to make an impromptu party of the occasion. Dawn’s current sorta boyfriend appears, plus some other guy. After dinner, joints are passed around. Being an abstainer, I take a pass. Things get weird. Susan, ever the manhunter, snags Dawn’s sorta boyfriend, adding one more lightning notch to her belt. They disappear somewhere in the house to fuck. Dawn goes off with the other fellow. Mary Jo and I are left making small talk, getting acquainted, sitting by the stairs, not exactly sure how this moment fell into place. The next day, we all go down to the beach. On the way up, in a secluded spot, Mary Jo, not to be outdone by her sister, makes a delayed move on the one male left unclaimed: me. Being a confirmed polyamorist, I oblige. It’s not the greatest experience I’ve ever had, but it’s better than nothing. The following morning we board the plane and are whisked through customs without any nasty interrogation process being thrown at me. Such is the life of the jet set, compared with those who go by bus. I am naive enough to believe that the incident at the border is now behind me. That assumption will be undone in the future, but for now, the way is clear for me to be able to resume following the general plan I came up with back in Florida – specifically, earning enough casual money to be able to move on to England before my US visa runs out.

The down side of the past three days is the realization that my relationship with Susan McTighe has deflated to that of being “just friends”. I can tell that she thinks me not worthy of the same level of connection to her that she initially seemed happy to embrace. The situation with Mary Jo proves even more disheartening. A few weeks after the border incident, in the short time that remains before I leave to help with the apple harvest in Michigan so that I can have enough money for the plane fare to London, Mary Jo and I visit a friend, Steve Bergman, who has a house boat on Lake Union. During the visit, I suddenly find myself sitting alone in the living room, not exactly knowing what is going on. Within minutes the audible sounds of Steve busily pumping away on a very receptive Mary Jo filter through the houseboat to where I sit. What can I do but quietly leave, feeling pretty irrelevant? Incidents like this serve to make me feel that my status as a foreigner in America is inherently inferior, irrespective of what my abilities and strengths might be. It becomes a recurring theme of my presence in the country that will continue to plague me for decades. It only adds fuel to the unspoken downgrading that Mary Jo’s sister, Susan, had levied on me with her behavior on that trip to rescue me when I was stuck in Canada. In the years to come, I will run across other immigrants similarly treated as lower class presences who are used either for casual novelty entertainment purposes, or as a source of cheaper labor, and that it is not the exception in America, but the rule.

Mission: Getting to London

Sept. ’74. The time comes to leave Seattle and the interim security of the Elliott Hotel and embark on the long, late-season hitchhike across the north of the country to Sparta, Michigan, where the apple orchard I’m supposed to be able to find employment at is. Bill Woods, who had given me the tip while we were picking oranges in Florida, will be there.

In the early morning of my first day on the road, I take the municipal bus to the end of the line and begin hitch-hiking on I-90. At Cle Elum, I get a ride with a beautiful girl in a Volkswagen Beetle. Her name is Marta van Amburg. When I tell her of my plan to get to London, she gives me the contact information for two friends there. Before dropping me off, in the spirit of the young of that decade, she pulls off so we can share a toke. I agree, only to increase the duration of our all-too-brief acquaintance. Once more, all the dope does is make me feel withdrawn. It spoils the purity of the moment. Ah well. We bid goodbye and I resume my journey.

I reach Billings by nightfall. My ride-giver offers a place to stay the night. I gratefully accept. After we have retired, he enters my room and asks if he can masturbate me. I tactfully decline the favor. Thankfully, he accepts my turn down. In the morning, neither of us mentions the incident. I resume my journey. On the other side of Bozeman, I am again propositioned by a guy in a big sixties-style car, but, unlike the other guy, when I say no, he dumps me on the side of the highway.

The rest of the journey is slow going, to the point that I opt to take a bus the rest of the way from Bismarck to Chicago and thence to Detroit and Grand Rapids. I sleep for most of the time, ending up as a pillow for the guy sleeping in the seat next to me. Oh well. By some process that will be lost to history, I arrive at the farm north of Grand Rapids that Bill Woods had told me would give me a job picking apples. It’s on Peach Ridge Road, just outside of Sparta. The owner is a man called Randy Kober. He is a dedicated apple farmer, very concerned not just about growing a good crop, but also with the quality of the apples harvested. He is how you’d imagine a real independent farmer to be – affable, physically robust, mild-mannered, slow-speaking and totally consumed, from first spring bud to final delivered box, by the dawn-to-dusk challenge of coaxing a high-grade harvest out of a scattered collection of groves boasting a number of different apple varieties. Picking is done into a bushel-sized canvas bag that has a wire frame. A drawstring allows the bag to be opened and closed at the bottom. This permits fruit to be gently offloaded into wooden crates that weigh around 600 lbs., when full. The picker is paid $8.25 for each box filled level with the top slat. The bag may not be as heavy as a bag of oranges, but this only means more ladder climbing per pound delivered to the box. I am still not fully recovered, energy-wise, from the hard battle with hepatitis and I find the work absolutely exhausting. My best day will be five boxes. My expenses for food are very small, though, so I am able to save some. I eat a lot of apples to be able to have enough physical energy for each day’s picking. Bill Woods and his wife are also part of the team of around a dozen. One of the other pickers is Buford. He’s a man of few words. Before a hard frost damages the fruit on the trees, we must somehow get 100 acres picked within a fifty-day window of opportunity. Recuperative breaks are infrequent. During one such occasion, I go into Grand Rapids and end up in a strip club. The featured act is an itinerant pole dancer named Lia London. Her act is pretty hot. She sits by me during a break and we chat. I tell her where I’m working. The money I blow this evening on the town will end up changing the course of my life in ways beyond my current ability to imagine.

A couple of days later, Lia stops by to say hello and ends up staying with me in my trailer. It is too cold for her. She’s from San Diego and this is Michigan in mid-October. The sex part of it is nothing to rave about. Being a stripper, she has to shave her pubic area and it’s my first intimate encounter with a shaven pudendum. I’m used to hair being down there, so it’s a turn-off. My conviction is that the emergence of pubic hair is Nature’s way of telling a girl she is ready to start becoming sexually active. From a young man’s perspective, if there’s fluff on the muffin, it’s ready for stuffin’ (encouragement given and legally permitted, of course). The tricky part is that when the hairless pudendum you’ve been invited to expose belongs to a full-grown woman, if you’re the empathetic kind, you don’t want to make her feel rejected at such a sensitive moment, so you see the whole thing through like a trooper, even though it might not be as exciting as you might have hoped for. That part I can do, but defending my overnight guest against the cold in this crappy wetback trailer-house is beyond my ability. She’s miserable and leaves after breakfast as I set out to recommence picking. Nothing more notable occurs between that incident and the wrapping up of the season.

Buford offers me a ride into Detroit, but in Grand Rapids, he stops to buy a bottle of whisky and asks me to drive the rest of the way south on the freeway so he can finally let go and get drunk, not having touched a drop during the picking season. It’s my first experience of driving on the right side of the road. We end up outside a bar somewhere in Detroit and bid one another adieu. Already considerably inebriated, he will get someone to give him a ride home and I go into the city center to catch a bus to New York. Standing at the counter in the bus station, paying for my ticket, I’m advised by a black fellow standing off to my left not to expose to view the cash I have in my hand. “You can get killed for less than that!” he says and he’s absolutely right. Downtown Detroit is a rough piece of real estate. It’s a late night ride. I sleep for most of it.

When we arrive at the bus station in New York, I am awed at the size of the buildings. I will forget what comes next, but somehow, I decide to try my luck at one of the major recording studios, the old fashioned way – playing my songs live. It avails me nothing, but in the process, I meet a large, friendly man, somewhat my senior, with a deep, commanding voice, who does regular voice-overs at the studio. When he discovers where I’m from and what I’m doing, he says he rents a studio apartment in an old building only a few blocks from Central that he isn’t using. It’s $45/week. Would I like to hold it for him, while I arrange to fly to London (for which purpose, having a South African passport, I won’t need a visa)? I gratefully accept. The man’s name is Doug Jeffers. He owns a house in Hope, New Jersey, and an abandoned farm in upstate New York.

Being in New York puts a drain on my cash. The room in question turns out to be an old tenement house in the middle of the block on 56th Street, between 5th and 6th Avenues. It comes with the usual endemic population of small cockroaches, which I attempt to reduce with bug spray kept by the door for rapid use after entering. The apartment below me is occupied by an avant-garde cellist, Charlotte Mormon, famous for performing either partly, or completely, nude and in other challenging contexts. We greet one another, going in and out of the building. She’s friends with Yoko Ono, whom I see with John Lennon, in passing, on the street one time. The neighborhood has many such personalities. I pass by Salvador Dali on one occasion.

I begin to realize that I won’t have sufficient funds for the flight to London, and while I Iook for a way to make some money under the table, the days on my visitor’s visa for the USA slip away. When it finally runs out, on the 4th of December, 1974, it’s a shock, but also a bit like a new adventure, suddenly being on the wrong side of the law – a thing forbidden, but survivable, if I keep my wits about me. Besides, what can I do? Curl up in a ball and die? Not likely! I decide to make the best of becoming an illegal alien, but I keep my packed backpack by the door, just in case I have to get lost quickly.

Life as Illegal Alien

All the while since leaving Cape Town, I have kept an address book. One contact in it is the New York phone number of the American wife of the bassist for the popular Cape Town band called HAMMAK (the name of which was derived from the first letter of the names of the original members of the band – Anton Fig on drums, Midge Pike on bass, Andre de Villiers singing, Keith Lentin on guitar, Henry Barenblatt on keyboard. Nicholas Pike and Amanda Cohen would join later, after Amanda had given my band, Wakeford Hart, the boot). The name of this lady is Susan Pike. She was the organizer of a string of high-energy mini concerts at the Art Centre in Cape Town. I remember her as being warm and encouraging, a big supporter of my erstwhile band, so I have good reason to think that she will welcome my being in New York and possibly help me orient myself better. It comes as a rude shock when she absolutely goes off on me over the phone, telling me that she is sick and tired of getting looked up by people she used to know in Cape Town. She does, however, give me a phone number to get in touch with Keith Lentin and Amanda Cohen who are now married, with a baby daughter. I go to visit them, which leads to my being introduced to Philippe Petit – the daredevil who had walked on a cable clandestinely installed between the twin towers of the World Trade Center. He has a compelling, mysterious presence and turns out to also be something of a magician, completely confounding me with his ability to make quarters appear and disappear with actions of flawless presdigitation.

November ‘74 to May ’75. Through an agency, I find a job selling hot coffee out of a mobile urn, first thing in the morning, to office workers in select commercial towers throughout the financial district. I’m just one in a team of such vendors. My supervisor is an Asian American a little older than myself. It doesn’t pay well, but sometimes people tip me. One of my designated spots is the 104th floor of the South Tower of the World Trade Center. The building creeps me out. It sways in the wind and I can see the surface of the coffee in the urn going from side to side when I’m up there. It sharpens my appreciation for Philippe Petit’s courage and willpower.

One day, my supervisor tries to induct me into the Church of Scientology, of which he is a fervent member. When I demur, he drops me from the team, without cause. It’s a deep cut to my confidence. Not once have I ever been anything but conscientious and dependable. I try busking down in the financial district in front of the New York Stock Exchange. After two hours of performing, having been passed by hundreds of well-dressed people, I have precisely thirty-five cents to show for my troubles. It is the first wounding devaluation in a long string of similar put downs that I will go on to experience for the next fifty years in America, but I also realize that such is the daily lot for many people where I come from, at the hands of the social class from which I myself come. I begin to realize that when it comes to empathy – in contrast to what I had allowed myself to believe – Americans, in general, have less of it than those I had lived among in South Africa and South America and that it is the ease made possible by wealth that induces them to be that way. I decide that only through assiduously tended personal connections will I be able achieve anything in America.

Open mic nights held at various bars and coffeehouses are no more encouraging. One disastrous try-out at ‘Catch a Rising Star’ is particularly bad for my morale. Fortunately, the employment agency finds me another job at a small grocery store in the Tribeca District, owned by an Irish-American family. As with anything I sign with to serve, I give the job my everything and actually improve the orderliness and cleanliness of the establishment – an attitude which is transferred from my past experience as an instructor in the South African army. The checkout person is a sixteen-year-old blonde girl named Kristin Weber. We become lunch break companions. Springtime in the outdoors in New York can be wonderful, especially in the company of an attractive, intelligent young woman overflowing with curiosity and a sense of life prospect.

The neighborhood is sketchy. One night, a bomb goes off in a garbage can on the street below my window, but no one is injured. On another night, I hear shots being fired nearby. Late, the night after, as I am walking down 56th Street toward the entrance to my place, toting my guitar after yet one more pointless open mic performance, I pass by a guard standing in a lit doorway. He engages me in conversation and then asks me if I want to play a song for ‘the girls upstairs’. What the heck, why not? It can’t be any worse than playing at the stupid open mic. We go up one flight of stairs and enter a small room lined with couches where scantily-clad girls are sitting under pink lighting. They’re bored. No customers. They’re open to hearing what I have to offer – it can’t be worse than just sitting there, doing nothing. I play a couple of songs and get more compliments from the prostitutes than the people in the bar I had previously performed in. During the ensuing banter, the two guards allow that they had shot and killed two would-be robbers the night before in the stairwell. They were off-duty NYPD cops and this was an after-hours side job.

Moving North

I’m just beginning to save up some money when I’m let go from the grocery store, without explanation. Maybe it’s a combination of my being undocumented and the owner feeling protective about Kristin. Whatever it is, I have been an exemplary employee and I’m deeply offended. The old man tells me that he has already talked to a fellow business owner a few doors down who could use help with his plant sales business. Maybe I should have taken him up on the offer, but the cut is too deep. I’m not enjoying life in New York City as a poor person and I have another offer: Doug Jeffers says I can stay at his defunct farm in upstate New York. He will pay me to work at deconstructing a couple of old buildings on the property – a barn and an old house. I decide to take him up on it, knowing only that it will be different from what I’m inherently confined to in the city. He drives me up there. It’s near a place called Messengerville, on the Tioughnioga River. The property itself is unfenced and about 40 feet from the road, which parallels a small stream. A decrepit, diminutive house is one of the structures Doug wants torn down. Between it and the stream lie the piled remains of a barn that I will discover the neighbor pulled down with a tractor so it wouldn’t collapse on their kids as they played in it. Across the stream, on a narrow strip of flattened land, sits an old shed. This will be my ‘home’ for the next seven months and where I will write, or perfect, a few of my more significant songs. Among them are, “These things are You”, “Grey is the sky”, “Poor Boy’s Song”, “The Hard Way”, “Going from my Mind” and “Harvest Song” – all, in one way or another, products of the life I had lived up to that point.

Doug returns to his work in New York City and I get down to the business of making everything around me work. I’ve got a handsaw, a large axe, a crowbar, a framing hammer, what’s in my suitcase and backpack, and my guitar. With the little money I can scrape together, I’ll add to that a kerosene lamp, things to write with and used cold-weather garments. In the remains of the house and barn, things like cutlery and cookware will be found. In fact, I find so many potentially useful things in among the tangle of lumber that it slows my work to a crawl. The crawl slows to a stop when I discover that a family of woodchucks has made its home somewhere deep in the ruins. Just like me, they are hanging on by the skin of their teeth. We are fellow hitchhikers on the highway of time and space and seeing them means more to me than a pile of ashes does. Anyway, there is plenty to do besides getting rid of the remains of the barn and house.

The stream runs year round, fed by heavy snow in winter and violent thunderstorms in summer. There are small trout in it. They’re pleasing to watch. Fifty yards, or so, downstream from the shack, sits a modest farmhouse occupied by a couple and their two children – a hot-looking girl named Colleen and her elder brother, Glenn. They’re long established in the area and have some kind of a store in Marathon, the next town on from Messengerville, by the river, on the highway toward Syracuse. They’re in the process of building a better, bigger house a short way up the road from the shack. Colleen, hot though she may be, is neither my type nor old enough to be of interest to me as a man, but she introduces me to her current boyfriend and we quickly discover a mutual interest in rock music. His name is Garry and he plays in a band performing around the area, called Maxx. Somehow, we end up working on some songs of mine. That leads to incorporating other members of Maxx in a serious effort to put on a decent concert at a large restaurant in the town of Cortland. The blend really works.

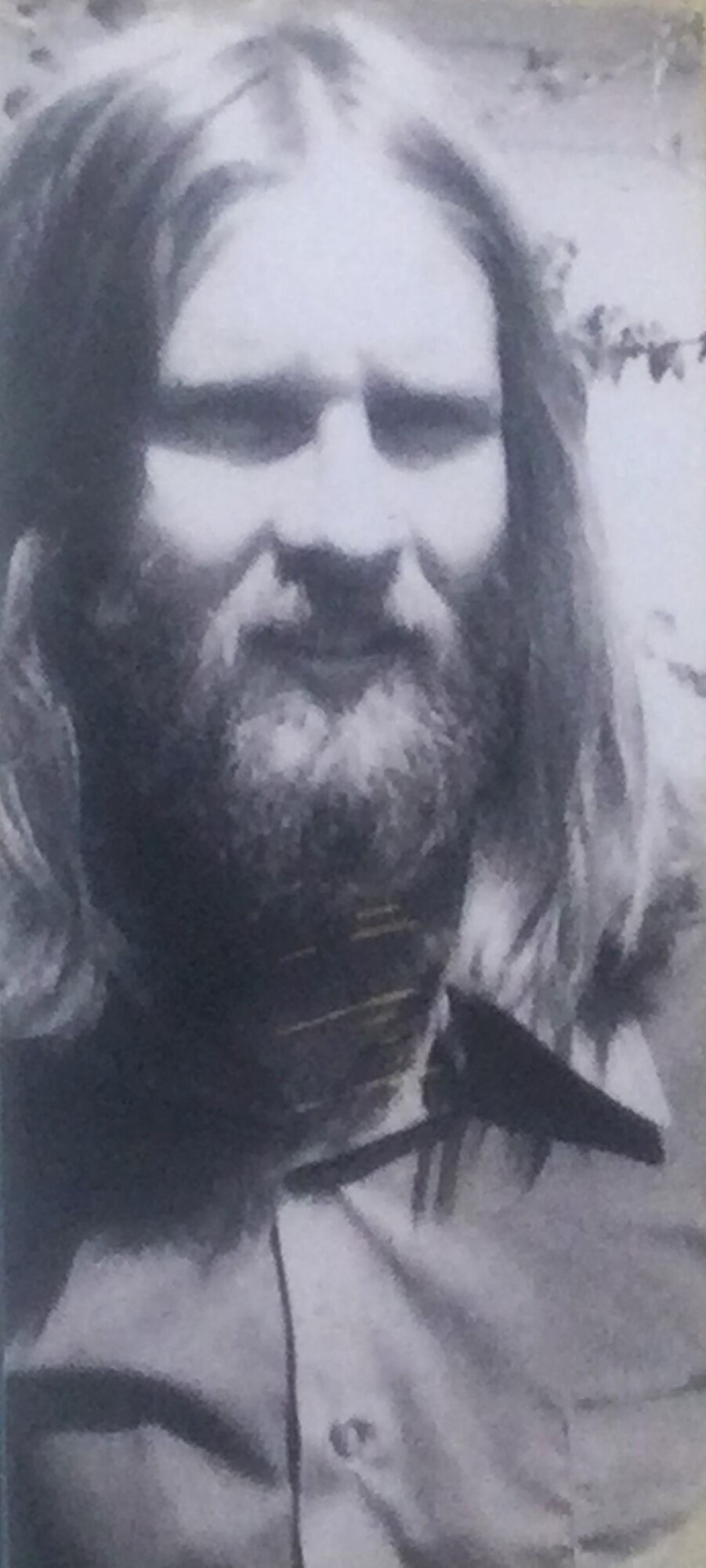

Meanwhile, there are other developments. Most importantly, I end up with a darling little black and white, short-haired kitten who attaches herself to me like a limpet, my hardscrabble existence notwithstanding. I call her Nukitius. From that point on, I become a lifelong ‘cat person’, though there will be dogs too. She will co-star in photographs with me that will be used in association with promoting my songs, more than forty years after she leaves this plane, cradled in my arms, dying of FIP, almost 3,000 miles distant from where she was born.

Not long after I set myself up on the shack property, a tall, thin older man stops by and introduces himself. His name is Tex Roe. He is a country singer, somewhat well known, who, later, will be inducted into the New York State Country Hall of Fame. We exchange stories. He and his family live just outside the nearby town of Cortland. In his younger days he was a member of the US Army Rangers. He shows me how to throw a knife, screwdriver or anything similarly pointed. Months later, confined to the shack, in the dead of winter, with the wood stove burning, I will break from either practicing my songs or writing letters and practice throwing a knife into a board across the longer dimension of the shack, the way Tex had shown me. One late afternoon, he picks me up so we can visit his friend John Tobin in Cortland. It turns into a long visit. Somehow, I end up being taken under the wing of John’s daughter, Mary. The interpersonal chemistry goes into overdrive and we end up quickly screwing on the floor of the garage, before returning to the main house as if nothing of any consequence had occurred. The incident doesn’t lead to any kind of relationship, but later, Mary gives me an address on a piece of paper for a friend of hers that I should look up, which leads to a similar encounter, only considerably more erotic. This is not unusual for Cortland in the mid-70s. It turns out to be, at least in that sense, more sexually liberated than NYC, partly because spontaneous indulgence in unfettered sex is a hallmark of the age – the Pill being celebrated as a sign of empowerment among women – and partly because Cortland is chock-a-block with young college students swept up in the intoxicating energy that the surrounding country exudes in spring and summer. This, of course, includes me. In part, it’s a global shift in consciousness among those of a certain generation and, in part, the quickening pulse of Nature in the Northern World, waking up in a hurry after the deep freeze of winter with its subzero Fahrenheit temperatures, calling on all animals in prime condition – humans included – to engage in those activities that lead to preservation of the species, despite what social mores may prescribe.

Tex Roe thinks that a song or two of mine, tweaked a bit, might work as country songs. I give it a shot on “It’s only one more time on the Highway” but can’t quite make it work. He then tries to connect me with someone he knows – a former high-level executive in the music business, now retired in the area. I meet the guy only once. We have nothing in common upon which to base some kind of intent to do things related to music. Shortly thereafter, I get a standard, boilerplate contract proposal which would basically turn me into a dancing monkey, deprived of any kind of decision-making participation. When I suggest modifications to the contract, he fails to get back to me. It’s not a great disappointment.

I go into town a few times a week, whenever being by myself at the shack gets too boring. One midsummer’s evening I show up at a party to which I’ve been invited in a casual way. It gets pretty crowded and loud inside – much more so than my current living arrangement allows me to feel comfortable with. I retreat to the front steps of the house. The evening air is balmy. Also sitting there is a pretty young woman. We get to talking. She is pleasant and friendly – just the kind a young man like me, newly arrived in the area, would like to meet. She offers me a pull on a joint and the sparks begin to fly. It’s the upstate summer effect again. Things get a little too steamy for the front steps and she leads me into the bathroom and locks the door. We don’t notice how hard the floor is during the next few minutes. It’s all over pretty quickly. No one seems to either notice or care when we emerge from the bathroom. She offers to give me a ride home and stays the night. It’s a great comfort for me to have a lovely, totally compatible young woman sleeping next to me, the crude circumstances of my dwelling notwithstanding. I sleep so deeply that when I awake, she has already slipped away and got on with her day. There, on my little table is a piece of paper with a beautiful poem on it – a true work of art. I will treasure it until I die.

To Peter:

It was so difficult to be sociable that night

when I wanted to be with you, only.

I could see your face in the darkness,

read your eyes in my mind,

merely your voice brought life into me…

and your touch? Well…

I look at you now

the sun dancing through your hair

the trees and grass whispering your name

and I feel content for the first time

in a long time.

I will always recall gentleness

and you.

I don’t get the sense that either of us is interested in a longer relationship. It has already become as magical as it can get – a short sweet song that lengthening could only diminish the appeal of. Nevertheless, I yearn for something more lasting, because I’m still not healed from the way Dawn, my first real lover, left me, back in Cape Town, or how indifferently she treated me when I visited her in Vancouver. The shack turns out to be a very important influence in my life.

May to Nov ‘75. The intensity of the land and the stream gurgling in the background is spiritually transformative. While there, I will manifest the most powerful and magical personal energy of my whole life, without even trying to do so – at once, animalistic and angelic. It will rise to an apex point and then gradually abate, irretrievably, all within a few short years. During the time it possesses me, without ever seeking it out, I will play a pivotal rôle in underpinning the lives of certain individuals whose own efforts end up profoundly changing the way the whole world works. I will do this despite conditions that become very harsh. It has a strangely seductive effect on select women – not all, that is; just those whose presence in my life is vital to my being able to survive and manifest what I have within me to contribute to Life and the World. Decades later, it will dawn on me that this transient spate of inordinate creative energy and insight was thought by the Greeks who built the Parthenon to be selectively dispensed by the god, Apollo, at his discretion, in the discharge of constructive and artistic destiny by mortals.

The gentle song of spring gives way to the full-throated roar of summer. A series of powerful thunderstorms rolls over the land, fueled by hot inland air passing eastward over the Great Lakes and being abruptly lifted to the crest between the Hudson and Susquehanna watersheds. One oppressively hot afternoon, I take a naked dip in the stream to cool off, just as a rumbling storm front moves in over the hills. It’s exciting being so exposed to Nature’s raw energy. My joy is abruptly shattered as a bolt of lightning strikes the ground with a terrifying crack a couple of hundred feet upstream of me. It is so incredibly loud and bright that the animal within me is immediately sent into a state of shock. Instinctively, I curl into a ball, absolutely terrified as another bolt strikes in the same vicinity. I dare not stand up, lest I act as a conductor for yet one more bolt. All I can do is lie there in the stream, trembling, covering my ears, hoping not to be killed, waiting for the highly active front to pass on, which it does after about ten minutes. It’s a lesson I will respect for the rest of my life: if it looks like lightning might be in the offing, value your safety and take appropriate steps to minimize the chance of your being struck. Don’t just wait to see how the situation develops, assuming Nature will be nice enough to give you fair warning.

The need to prepare for surviving the brutal cold of winter ahead has me thinking about how I might put together my own wood stove, so I can keep the shack heated. I settle on using four used car wheels, three with centers cut out, for the combustion chamber. I use 1/4-inch steel plates for the cook top, bottom and door box, and empty commercial-size food cans fitted into one another for the smoke stack. For the air control and ash clean-out, I use a piece of 3-inch threaded pipe with slots and a pipe cap. I rent a gas-driven arc welder and an acetylene torch for cutting. After a bit of practice, I am able to cut the needed pieces neatly and do a respectable job of welding them all together. I finish it off with a hinged door equipped with a sash lock. To prevent the roof from burning, the stack goes through an oblong hole in a larger piece of sheet metal. Incredibly, though I’ve never done this kind of work before, the end result looks pretty good and works just fine. Beginner’s luck, no doubt. But that’s just the beginning of the work needed; a lot of wood must be gathered, entirely by hand, to have enough fuel to keep things bearable inside the shack. Fortunately, the volume of air that needs warming is pretty small.

Doug Jeffers sends me a small stipend for caretaking the property. It barely meets my most critical needs, but I manage to save enough to have the occasional beer in Cortland and hang out with other people. On a whim, I decide to look up the young woman whose address Mary Tobin had given me. I knock on the door. A very pretty Chinese American girl opens it. It’s clear that she already knows that I’m a friend of Mary’s and she invites me in for tea. I make no assumptions about her, because I know nothing about her. What I expect is that we can chat a bit, after which I take my leave and get about doing whatever other plans I had. Well, no sooner do I sit down on the couch than she is sitting next to me, quite clearly with intentions of getting it on, right there and then. I’m not really sure what to make of the situation, but it becomes clearer when, after a little foreplay, she takes my hand, leads me into her bedroom and closes the door behind us. The next couple of hours are the most sexually intense and unrestrained I have yet experienced, almost surreal. Anything I put into it, she responds to with equal fervor. It rises and falls in wave after wave of renewed intensity and rest. After five mutual orgasms, I am finally exhausted enough to call it quits. Almost without ceremony, I take my leave. We will never see each other again, though once, I do try to visit her at her dorm in the university. We talk briefly over the intercom at the entrance, but I sense no welcome in her tone, nor any inclination on her part to come down and meet me at the door. Immediately, I am wary. Females who give me mixed messages or play coy are females I steer clear of. Some men and women enjoy cat and mouse games of one being the pursuer and the other playing hard to get. I don’t. To me, it’s a stupid waste of valuable time on Earth. I make no further attempts to see that girl, but not without sincere regrets. That degree of sexual compatibility is rarely encountered in a human life. You’re left wondering what kind of amazing relationship it might have supported had a few small factors been different. Sex is nothing to be dismissive about. Without it being a pleasure to be sought, the continuation of human life becomes just a chore fraught with a great many burdens and discomforts and, thus, highly unlikely to be embraced.

Fortunately, I don’t have to dwell on this disappointment for long. There is a bar in Cortland called the Dark Horse that is chock full of college-age people just about every night. Between the music and the hubbub, it’s incredibly loud in there. I’m in the crowd one evening and I meet a beautiful young woman whose smile and eyes speak volumes of a kind, honest and spiritually-developed soul within. The appreciation appears to be mutual and a new friendship begins, straight off the bat. The romantic side, in this case, grows more slowly, but the lack of anxiety attached is most welcome – no sudden switches, no caprices. Neither of us seeks to make an exclusive relationship of it. To begin with, she already has a sorta boyfriend. He’s the owner of the Dark Horse. His name is Jimmy. For my part, in the manner of others of the hippie generation, I’ve grown to value my sexual independence – the unimpeded right to have sex with any woman I choose, at will, whenever and wherever the opportunity arises. Her name is Marilyn Rosché. There’s not much evidence of Jimmy being around. In fact, I never see him. By contrast, my friendship with Marilyn deepens. This means cutting out ever more time to visit with her from the time I spend attending to making my little home at the shack ready for winter. Having Nukitius as a shack-mate is no problem. I can afford to feed her. But two small mix-breed dogs show up, probably dropped off by somebody unable to care for them. They’re both females. I call them Gertrude and Ethel. One day, I notice that Ethel has a really fat belly. I find out why when Glenn from the property downstream shows up to inform me that she killed one of their free-run chickens and ate it. I’m dismayed at the situation, apologize profusely and promise to keep a closer eye on them while I try to find a them a new home. It takes me months. By pure chance, one of my new friends in the area happens to work for a pet shelter. He manages to find homes for both dogs some time in late January.

That’s not the end of it: another dog – a male Beagle – shows up. I call him September. He’s a really nice little fellow. For the first half of the ‘75/‘76 winter, I spend most of my time at the shack, keeping it lived in and warm, when temperatures dip. The snow comes on, big time. By early December, there’s a permanent cover of it over everything. The ski run at Greek Peak opens for the winter season. The unusual nature of my existence is enough to induce one of my new acquaintances – a photography enthusiast – to suggest doing a photo-shoot out at the shack, with a deep blanket of snow over everything. It’s just for the novelty of it. We have a lot of fun doing it and a week or so later, he gives me copies of the prints. They’re unexpectedly good. Nice as they are, I have absolutely no idea how important it will be for me to have them four decades further down the road.

By New Year, temperatures out at the shack drop to below 0° Fahrenheit. It’s a colder than usual winter, but the drop is so steady that all of us adapt. Being a travel-hardened 27-year-old former boy scout and soldier helps a lot. Even so, it really is nice to be able to hitch a ride into Cortland occasionally and visit people in their warm homes, particularly Marilyn. During these outings, I don’t worry about whether Nukitius and the dogs are okay out there in the shack. Sure, it’s cold, but nothing life-threatening for animals that have acclimated to the gradual shift in temperature. In the third week of January, however, a front of inordinately cold air moves in while I am in town visiting Marilyn. Morning arrives clear and cold – minus thirteen degrees in the sun. I get Marilyn to drive me out there to check on Nukitius and the dogs. When I open the door, I’m hugely relieved to find them all alive. The the dogs are huddled together on my straw bed, with the cat next to them in a tight, shivering ball. I fire up the wood stove and feed everybody, but it’s clear that getting through the night has been hard on them. Later, Glenn will report to me that the temperature outside had dropped to minus 26° Fahrenheit. Poor little Nukitius! In the struggle to stay warm enough, she has burned up her soft tissue. Her normally perfect black and white coat is filled with tiny skin flakes. It pains me to the core to think of her struggling through the night to stay alive. I feel very guilty about not having come back the previous evening. She and I have grown to have one heart together. As a result of this lesson, to the last of her days, I make sure she never has to suffer through another night like the one just passed, wherever our travels together lead us. The experience is a big step toward my becoming a dedicated cat guardian, for life.

Being tied closely to the shack, so it can be kept habitable for all of us, has the upside of providing plenty of time spent working on writing songs and improving my skills. I have notions of doing a live performance somewhere in the area. Garry Bordonaro agrees to try working on some songs, which we do at a house up the road in Dryden, where the band practices. Being neither a great singer, nor an outstanding guitarist, I don’t like performing solo. It involves too much nerve-wracking exposure. What I have shown that I can do well, however, is to be the front man for a well-rehearsed concert band of competent musicians, with an emphasis on bringing to the fore the stand-out skills of as many members of the band as will fit into the overarching sweep of an integrated show. When Garry and I discover that the songs I have go well with what he has to offer, it piques the interest of other members of Maxx and the prospect of doing a concert shifts, first into higher gear, and then, into a committed intention, requiring substantial upfront organization and practice time. Everyone in Maxx gets onboard the train but the guitarist – I can sense that he feels crowded, that I’m an interloper. It’s a disappointment, but I just have to roll with it and be grateful for whatever backing I can get. Besides Garry Bordonaro on bass, there is Al Macomber on drums – a significant assist, being that they’re already accustomed to working together – and Michael Amdur on electric piano. The band has its own amps and PA system. All of this forms a solid base upon which to add a couple more people from outside Maxx – Peter Bennet on harmonica and Judy Sills on flute. To get her parts down, Judy and I have to work together, alone. Inevitably, this leads to having sex together, but, once more, it’s a fleeting thing of no lasting consequence, characteristic of the time and place in which we happen to be young adults. Peter Bennet also has a 1/2-inch tape machine, permitting recording of the actual performance, in the hope that we can get some decent demo tapes out of the effort. A venue is arranged – the lower level of the Cortland Mini Mall, below Mother Courage, a restaurant with a youthful, earthy identity and a hip following. There will be two concerts, a week apart. To bring people in, the ticket price for the first will be only half a dollar. The next concert will be a buck-fifty. All of this occurs as the spring thaw sets in.

When I’m not working on either the music, or out at the shack, I like to spend time with Marilyn, visiting her often at the the house on Tompkins Street that she shares with a young couple. Even so, I feel a sense of persistent inferiority when I dwell on our very differing circumstances – she, the one with a university degree from Cornell, a good solid position, making a decent income working for Headstart, with an approving and supportive family and me, an illegal alien, university dropout, family black sheep, social outcast and fringe-dweller without a penny to his name. All of these unfavorable touchstones of comparison are facts, not unfounded paranoia. They undermine any sense of true equality with her that can be had and oblige me to acknowledge the uncomfortable truth that, in being with her, I am also being carried by her, both materially and psychologically. Given my present circumstances, the best way I can see to redress this asymmetry is to succeed convincingly in the only field in which I currently have some skill – music – a prospect so remote I scarcely dare to even entertain it, even as I strive to achieve it.

The advent of spring brings an important change – Marilyn moves to a second storey apartment in a house on Cayuga Street in Ithaca, where Cornell University is situated. It affords a greater degree of privacy. There’s also a small garden plot next to the house. Down the street a block or so, Fall Creek lives up to its name in its final plunge off the tableland above to the level of Cayuga Lake, one of ten such finger lakes west of Syracuse whose outflows run northward into Lake Ontario. I’m told that where the entrance road to the university grounds passes over a bridge high above the creek, various despondent students have hurled themselves onto the rocks below. I prefer to consider this more lurid legend than historical fact, but given the pressures behind obtaining a degree from Cornell, it certainly seems possible. Among the downtown businesses in Ithaca, there is an unpretentious café that is quite famous, thanks to the successful cookbooks put out by its owners. The café is called Moosewood. It’s a social hub for the area community. Marilyn and I go there every now and then for coffee and a piece of cake. It’s what we can afford. Owing to the longer commute between the shack and Ithaca, versus Cortland, my home base now becomes the apartment I share with Marilyn. Nukitius, my cat, and September, the beagle, come with me. Two’s company, three is bearable, but four is definitely a crowd. The property is just too small and neither Marilyn nor I ever set out to adopt and take care of a dog. We let him out when he needs to pee. It works for him and it works for us. One morning, after having let him out, while we are watching him through the window, a woman walks by and stops to pet him. The next moment, she walks away with him following her. At first, we think he’ll stop soon enough and come back, but he doesn’t. I’m about to run downstairs after them, but in the moment that Marilyn and I exchange looks, the decision is made: let’s just see what happens. September never returns. We are certain that the kindly lady has now taken over responsibility for him, but still, a degree of shame attaches itself to the memory of that moment that I can never be fully confident is unwarranted. It is only the first of such accommodations occasioned by being dirt poor that I will experience over the course of the next four decades and each will leave a significant dent in my sense of self worth.

Marilyn owns a very small car – a Mazda. It gets good gas mileage. We can’t afford to just idly explore the surrounding countryside, but we do make some longer trips in Northern New York State to be with members of her family on special occasions like Thanksgiving. I meet her parents on one such occasion. They have to take care of Marilyn’s younger sister and brother, Susie and Robert, both of whom have a terrible congenital condition in which a gradual loss of hearing, eyesight and cognition sets in at the onset of puberty, leading to an early death. Neither is yet twenty and both must be spoon fed. It is a very sobering thing to see the impact that this awful genetic malfunction has had on Marilyn’s family. From Marilyn, I learn that for it to manifest in a child the gene responsible must be recessive in both parents. Even then, not all offspring will manifest its degenerative effects. The odds are even that the gene, though passed on, will remain dormant. So, although Marilyn and her older sister have grown up unaffected, their two younger siblings have expressed the gene. That Marilyn carries the gene and will pass it on to any children she has is not something I want to be part of. The only sure way to save other children and their families from experiencing the same terrible fate is for those who carry the gene to not have children. It’s nothing to get overly exercised about. Billions of people never have children and they live perfectly normal lives. That’s just reality. What is also reality, however, is the fact that, whether they go on to have children or not, the majority of people seem to value the potential of being able to do so during the window of time when that is possible and don’t like being confronted with factors that impinge their ability to choose.

I find work painting a house, entirely by brush application. For the owner, it’s a steal, because he pays me by the hour – a paltry $5 for the labor and nothing for the value of the work, which I render unstintingly. One afternoon, the temperature reaches 98°F, with oppressive humidity. I have to repeatedly soak myself with the garden hose to stave off getting heatstroke as I work. Illegal aliens have to take whatever shit work they’re offered. People know this and happily take advantage of it.

By this time, I have been given the use of a bicycle. The hills around Ithaca are a stiff challenge but I get stronger with time. It’s a step up from just walking and increases the range of my daily travels – both for pleasure and prospect. I’m no longer dependent on others to be able to get out to the shack during the warmer half of the year. I still go there, but less often now. The visits are a combination of nostalgia, checking up on the things of mine that still remain out there and making sure that, if push comes to shove, I always have a place to retreat to out there. Over the course of a life lived entirely in premises owned by other people I have learned the value of never assuming I have an unassailable durable right to the roof over where I lay my head at night. The shack is the closest I have ever come to owning that right.

As close to a couple as Marilyn and I have become, from my point of view, at least, we are not exclusively so. Nor does she ever make such a claim on me, even though I know that it probably isn’t an optimal arrangement for her, that she may even be wasting precious time indulging me in her life, given that she is at an age where she must act soon if she wants the best chance of being a mother and a wife of the more conventional type. We don’t discuss it, but the thought worries me, because the last thing I want to do is hurt her or compromise her hopes. I’m acutely aware of how much I owe her for my very survival in a country where, from a technical and legal point of view, I am not welcome. The main problem is my central objective in life: I’m still dead set on making a big dent in the American music world while being in my prime affords me the best opportunity of doing so. That vision includes the necessity of touring. As I see it, it’s the ONLY option open to me that will both cure my illegal alien problem AND bring in some money, so I can get out from under being so dependent on others to be able to even eat. I believe that being seen as a voluntarily single young man comports best with that ambition and because of it, as long as my sights continue to be set on attaining that lofty goal, I refuse to be tracked into a more conventional life path, or even allow anyone to believe that I might be drawn into doing that. It’s a reality I take pains to explain to those I get close to. The last thing I need at this time is to have anyone think I might be able to be tied down in a way that relegates my musical aspirations to a lower tier.

The Concert in Cortland – A Mixed Outcome

Marilyn is deeply involved with her career at Head start. She isn’t just a kind person; she is a very intelligent, ambitious one, with a measured IQ of over 140. It’s also true that she might not want to be tied down to a life of serious domesticity at this time and that the way things are with the two of us, for now at least, works for her too, even if it isn’t what social convention may applaud. Whatever the case, she proves to be an invaluable ally and facilitator in my musical efforts, especially making the concert happen at Mini Mall, the logistics of which are a huge challenge to a person of no means, like me. She makes sure I get to the practice sessions we all need to be able to pull the thing off and helps with the advertising in the run-up to the performance. I make up pamphlets, using a short cartoon format I think might lead people to more readily be curious about the event. Many businesses in Cortland and Ithaca agree to display them. It’s a big team effort on behalf of someone who is a de facto nobody. Radio host, Bert Shapiro, at WKRT, the local radio station in Cortland, even gives it a big plug by featuring a ticket giveaway on his afternoon show. Mother Courage provides its chairs for the occasion. We give the first performance of the concert at 9:30 pm on July 7th- an average Wednesday night in small-town America. A paper program, with all the relevant information and tributes, is made up by Marilyn and distributed. Attendance is robust – around 200 – and lively, with a lot of energy coming from the audience to help with the performance. Max starts the ball rolling with a five-song set. We then all combine on stage, as Amethyst, and perform two more sets comprised of songs of mine – fifteen in all. A spirit of concordance rises to a climax with the last song – Take Down the Old Flag – that closes the show. The collective effort, though small in scope, is a success, eliciting a rousing ovation. In the week that follows, before we repeat the show, Mother Courage runs an ad in the Cortland Standard:

Did You Hear Amethyst Last Wednesday Night?

If you didn’t, you probably know someone who did. Two hundred curious or informed concert goers came to see this almost unknown, newly-formed group. They gave them a standing ovation. After this Wednesday’s concert, Amethyst will be dissolved, to be reformed who knows when, much like the Aurora Borealis – or perhaps, the passenger pigeon. So don’t let this concert pass you by. Mother Courage will be serving wine & beer. Location – Basement of the Mini Mall. Time – 9.30 p.m. Admission $1.50.

A favorable review comes out in the local paper after the first concert, raising our hopes for the second. A copy of it will become something I hold in safekeeping through many life chapters in the years ahead. It goes as follows:

“Never Hear Anything Like It For So Little, Again – -“

Never before Wednesday’s “50-Cent Concert”, presented by Amethyst, has the basement area of the Cortland Mini Mall been filled to capacity. Just over two hundred curious scene-seekers, night-goers and music devotees gathered to hear the sounds of the totally unknown group. There was some seating, but for the most part, people sat on the carpeted floor.

To have drawn together such an audience in the basement of the Mini Mall, where both the Mid-Winter Music Festival and the relatively popular Peabody Band had failed before, was in itself a victory of sorts, attributable to some very astute advertising. To keep them there would require nothing short of a very good show. And though the concert continued for all of two and a half hours, there was still a capacity crowd when the last rousing chorus died away.

“You will probably never hear anything like the 50-Cent Concert for so little again”, stated the poster advertising Wednesday night’s performance by Amethyst, and failing some very extraordinary future developments, that claim was more than legitimate.

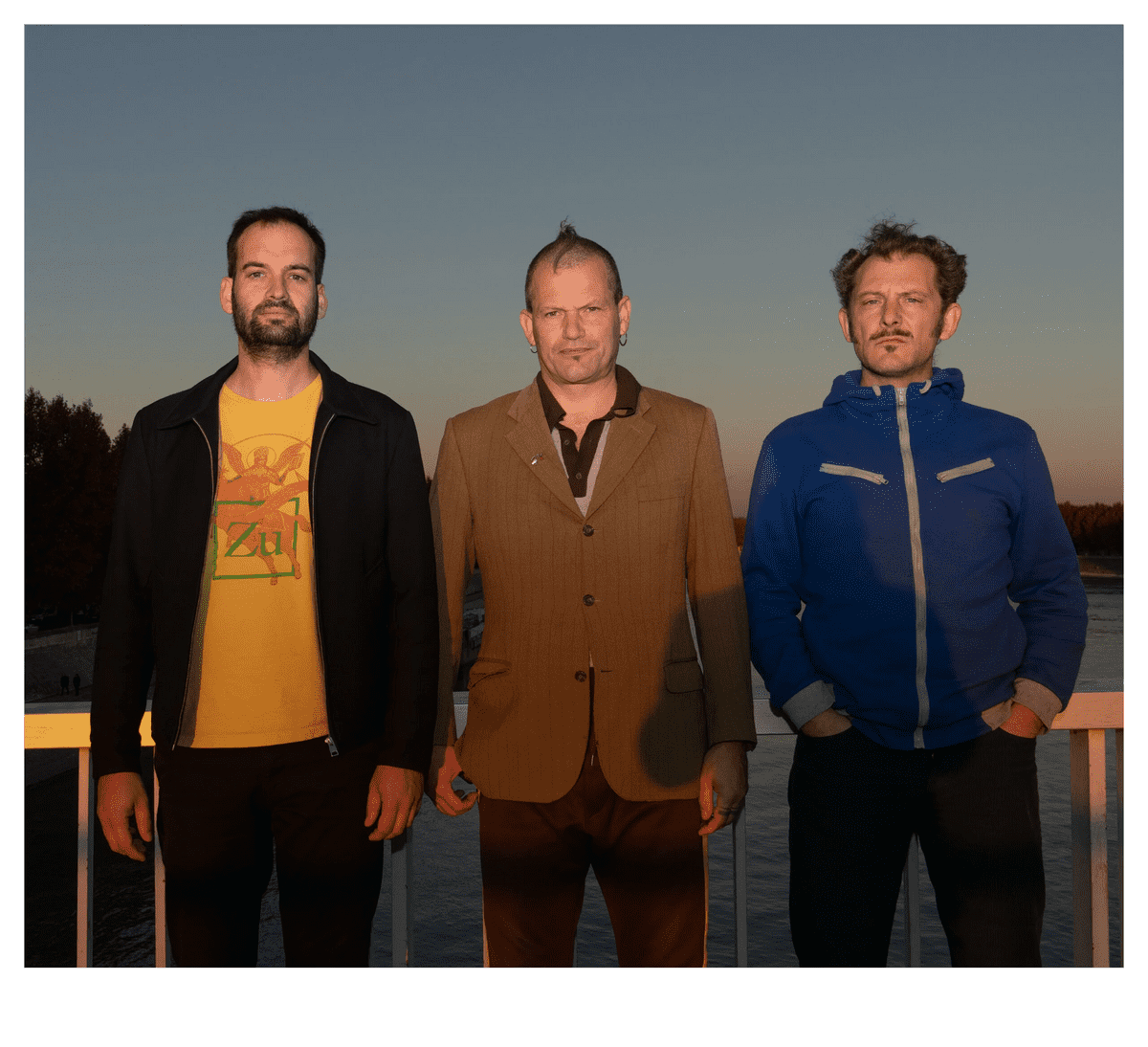

Amethyst consists of six local musicians – Michael Amdur, a classical graduate of Ithaca College on piano and organ; Garry Bordonaro on bass guitar; Al Macomber on drums; Judy Sills on flute; Peter Bennett on harmonica; Peter Wale on acoustic guitar and vocals. All the music played by Amethyst on Wednesday night was composed and arranged by Peter Wale.

Three of the members of Amethyst- Michael Amdur, Garry Bordonaro and Al Macomber, along with a guitarist, Alan Bradley – normally play in a group called Max. It was in this capacity that they opened up the evening, playing some tightly arranged pieces by Bradley.

Thereafter, Bradley retired to the audience, Peter Bennett, Judy Sills and Peter Wale came onstage, and the band became Amethyst. The music they played cannot be defined as rock-and-roll – though the elements of rock were definitely there – nor as anything else. It seemed rather like an eclectic blend of styles in a unique setting with plenty of variation, a gentle, melodic hybrid that seemed as palatable to the older members of the audience as it was to those still in their teens. The lyrics were not always as gentle as the music, with phrasing in certain songs as keen as a scalpel.

Amethyst and Max will be staging a return engagement Wednesday night, July 14, again at the Mini Mall. After their second concert, Amethyst will be temporarily disbanded, says Peter Wale. It’s purpose as a vehicle for introducing his music to the community will have been accomplished.

As for the future of the basement area of the Mini Mall as a concert venue, much can be said. The acoustics are good, the atmosphere is intimate and refreshment facilities are right on the premises in the form of Mother Courage and John’s Hot Dog Stand. All that remains as a big question mark is the level of entertainment, the management expertise and the degree of response that can be elicited from the public and the area news media. With acts as fine as Amethyst and recording artist, Charlie Starr, there is some reason to be optimistic.

To our great disappointment, the second concert only draws around half the number of the first one. Playing to a half-full house after having experienced a full house the previous week is a significant downer for all the players. In one way critical to any ensuing success, the strategy behind doing the two concerts is coming unraveled. My presumption that a successful first performance would lead to an even better attended second performance proves to be wrong. Nevertheless, we give it our best shot. Of course, the second show’s audience is also aware that the house is half empty, significantly reducing the potential for it to develop, within itself, a sense of collective assent that what is being shown and heard is, in fact, a stellar effort worthy of unstinting approval. Applause is generous but nowhere near the energy level of the first night. The following week, a letter to the editor is published in the paper, which corroborates the disparity between the two events:

Good Music Unappreciated By Cortlandites

To the editor:

Come on, Cortland! I swear I can’t imagine what is wrong with you, particularly younger people. I’ve heard so many of you complain that there’s no good music to be heard in town, and yet when there is, nobody comes to hear it!

Last Wednesday evening (July 14th), a group called Amethyst entertained those of us who bothered to go, with a concert in the lower level of the Mini Mall for the very reasonable price of $1.50. The previous week, the same concert was performed for 50 cents and, expectedly, the lower level of the Mini Mall was full. This week, however, barely a hundred people came. I, myself, was disappointed, but more than that, Peter Wale and his group were disappointed and, believe me, they felt bad. They have worked for two months to get these two concerts organized, as have other people, and because of the difference of a dollar in admission price, the second one was a financial failure. Those people went virtually unpaid for all their efforts because no one cared.

Now Cortland, before you begin your oldest refrain, let me tell you that these concerts were equally well advertised. There were posters prominently displayed in many of our local stores, restaurants and places of work – including Wilson’s, Brockaway and Smith-Corona. Bert Shapiro of WKRT did a ticket giveaway on the air last week and out of six tickets given, two people came to pick them up. And I’m sure many of us who attended the first concert passed the word around. The quality of the music was excellent, both times. This was not a second-rate group, Cortland. They’re not cut from the same cloth as most around who play locally. They had the talent and the musical ability right up front, but they didn’t have you, and that’s what makes all the difference.

Bonnie Slocum

Cortland

My gambit of something building on itself having failed, I am left spent and depressed after the whole concert effort. I am well aware that chances like that given me by the generous contribution of credence, time and effort by the members of Max, will not come again soon.

If my expectations had been met or, better yet, exceeded, I could have provided a persuasive precedent in shopping for a deal with either a record label or for competent assistance in logistics management. Then again, it could be that the time for my songs to go out to the world is not yet ripe. Naturally, this is not an easy rationalization to make and in no way helps to assuage my disappointment, given that so much that is in the balance for how my life goes hangs on how well my music does in the world. What else of unique significance do I have to offer?