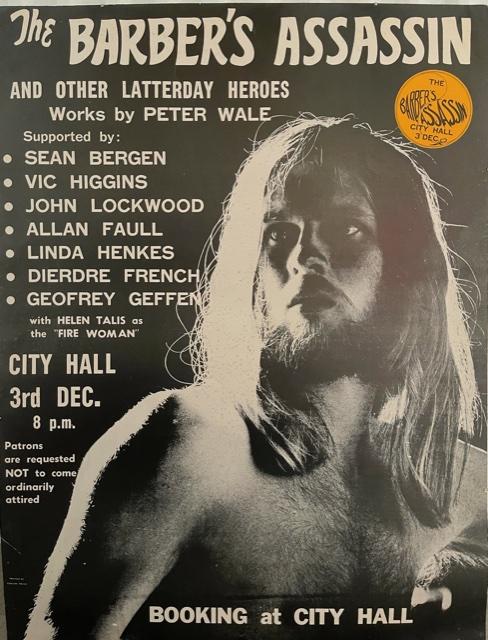

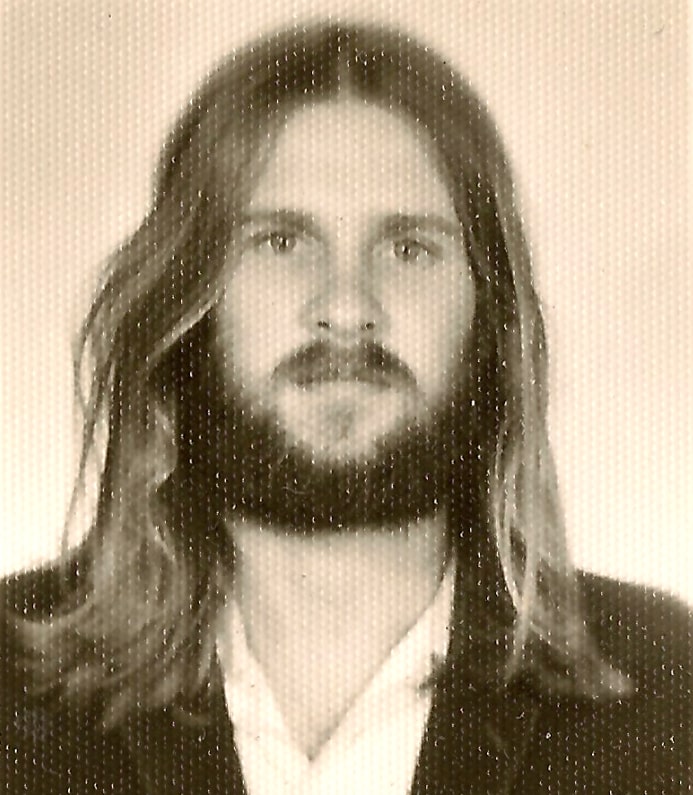

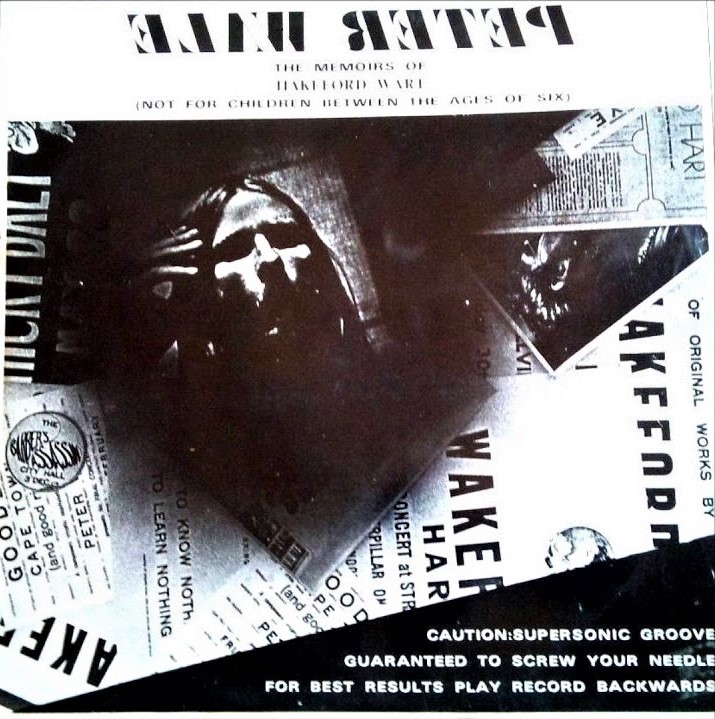

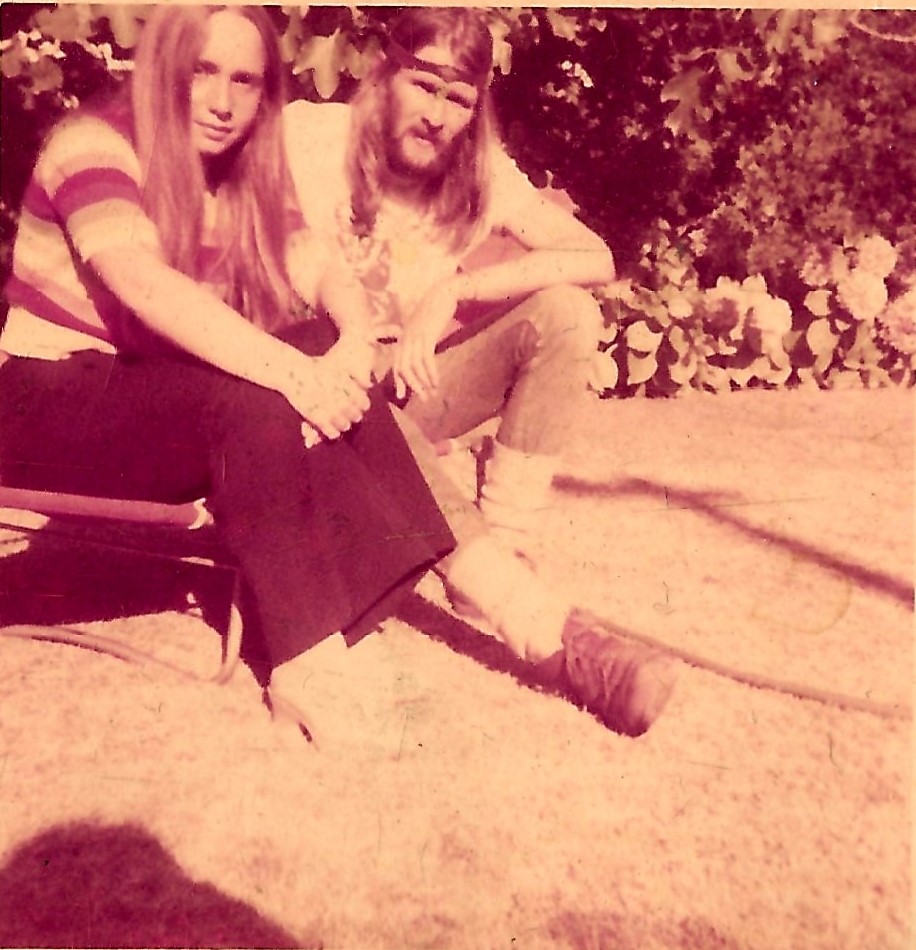

Peter Wrenleau (Wale) | Interview | “The Memoirs Of Hakeford Wart (Goodbye Capetown)”

In 1972, Peter Wrenleau, known as Wale, unveiled a remarkable LP. After years of obscurity, the album has resurfaced, and today, Strawberry Rain is gearing up to unveil a special edition featuring 14 tracks (a significant expansion from the original 4)

Hailing from South Africa, this masterpiece is a fusion of psychedelia, prog, and folk, embellished with enchanting flute melodies and electrifying fuzz guitar. These recordings capture the essence of Wale’s final concert before embarking on a yacht towards new horizons. Dive into this extraordinary compilation, a testament to timeless compositions and an evocative journey through music history.

“Life is a dance, not a march”

Where and when did you grow up? Was music a big part of your family life? Did the local music scene influence you or inspire you to play music?

You know, a lot of people might say that I never really grew up, although I did, of course, grow older with the passing of the years. It’s still a journey of daily discoveries and growth for me, always trying out new things. The external manifestation of a man with a grey beard, has not extinguished the child which served as the basis for the man. Both exist as options, depending on what is appropriate in the moment. Nevertheless, I get the point of the question and will stick to the facts expected.

I began my earthly life in late November, in 1948, in Cape Town, South Africa, which at that time was a city of only modest size. I was a quintessential post World War II baby, born to parents rather more caught up in the general euphoria of the time than they should’ve been. My dad had survived both the campaign against Rommel in North Africa and the liberation of Italy from the Fascists and the Nazis. Luck just HAD to be on his side. What could possibly go wrong? My dad was the returning hero, a super athlete of good family stock and very ambitious. My mother was a vivacious, 19 year old package of artsy bohemian fun. Unfortunately, for them, Mother Nature was right there too, quietly riding along in the back seat, and resolutely intent on replacing the lost of the War with new replacements and, before they really had time to think about it, well, there I was – a gurgling, guzzling, nappy-soiling, bawling bundle of ambivalence, not exactly welcome, certainly not convenient, undeniably part of the Wale family, for better or for worse. What my mother wanted was a career in the theatre, not a baby, sucking on her tit. Thank God for the colored family cook, Louie van Schalkwyk. She didn’t have designs on stardom ; I was the star in her limited universe. She doted on me and when I was two, saved my life after I fell in the garden pond and nearly drowned. My mother pulled me out and, finding me unresponsive, screamed, “Oh my God! He’s dead!” and promptly fainted. Louie rushed out of the house, grabbed me, got the water out of my lungs and restarted my breathing. I got pneumonia, but survived. Of course, I don’t remember any of this, but it’s what I’ve been told. Maybe the hypoxia damaged my brain. Some would say, definitely! Though I turned out to be academically adept, I was constantly reproached, or teased, for being slow.

The earliest clear recollection I have of my natural mother is her waving from the deck of the mail boat as it set sail for England. On the quay were Louie, my three year old self, and my one year old sister in a stroller. My father was notably absent. The year was 1951. I would not see her again until 1971. The year that followed, the family was my father, two tots and Louie, the family cook, at the dinner table together. It was a bit of a rough start for my sister and me, but we didn’t see it that way because we had nothing to compare it to. Actually, having Louie as my stand-in mum was just fine by me and if I’d been in charge of things, I’d just as soon have kept it that way. Of course, my dad needed a wife and, in due course, he found one – my stepmother.

Based on his connection to family status and family wealth, my father was a premium catch for my stepmother who, for reasons I was never told, had moved away from Bulawayo in Southern Rhodesia and come down to Cape Town. I was the downside of the deal. Some women see every child as a gift from God. Well, I was a child, no doubt, but I was also anything but a gift from God to my stepmother. An unavoidable inconvenience would be more like it.

Whatever it was about me that got on her nerves, I can’t really say. All I know is that at her insistence, during the school year, I was confined to living in two boarding schools for nine of my initial 18 years on the planet and the reasons had nothing to do with academic advantage. The first school was Western Province Preparatory School, only a mile from my home. The second was St. Andrew’s College, 600 miles away, in Grahamstown. Achievement, rather than enrichment, was the primary ethos behind how both schools were run. Slackers and miscreants were beaten with canes. There was no privacy to speak of. Weird sexual behavior included not just the adolescent boys but masters, as well. Then again, when you first encounter it, sex itself, is weird, and generally open to a lot of ad hoc improvisation. So what’s new about weird sex experiences? People have been weird that way for ever. If you doubt me, read the Bible. Talk about weird! In fact, it’s not normal to grow up and never have any weird sex experiences. That kind of weird is normal. So it wasn’t that side of things that left a shadow inside me. It was the relentless reliance on various forms of physical violence to achieve results and the absolute absence of adult affection that really stuck it to me.

So it’s somewhat ironic to have to admit that though I do not celebrate having lost so much of my childhood potential to those institutions, I’m still very much a product of them. Pain is not a reason to give in, or give up. Positive feedback is not necessary for the continued output of effort, even if the score is not in your favor. Hunger is simply the amplification of the potential for the enjoyment of the ultimate sating of it. Etcetera, etcetera. You get the picture, no doubt.

A little bit of that ethos is a good thing. but when it becomes all-consuming, you become a kind of Quixotic figure, tilting at windmills, unable (in the words of the great Kenny Rogers) to know when to fold your cards. The Don Quixotis of our time are, in many respects, those who aspire to succeed in some facet of the arts, instead of, say, getting a steady day job. The double irony of this is that my parents, in sending me to these achievement obsessed schools, so that I could become a successful professional of some sort, actually contributed to what it would take to keep me plugging away at making my mark in the music world.

No doubt, you’ll be happy to hear that there were other, more enjoyable sides to growing up, mostly experienced during the school holiday parts of it.

I absolutely loved going fishing, whether it was 20 miles off Cape Point, in search of tuna, in my father’s game fishing boat, up some lonely stream in the Hottentots Holland range, catching trout, sitting in a rowboat on Zeekoevlei, waiting for carp to take the bait, or out on the estuary of the Breede River fishing for one of a dozen different species. Just being out there with the water, normally in the company of a friend, filled my cup.

The area around Cape Town is fringed by a range of mountains that rise to an average maximum of around 6,000 feet – just enough to capture the moisture of the winds that blow off the ocean, while leaving some for the hinterlands beyond known as the Great Karoo – a vast region of semi-arid scrublands. In these mountainous regions two rivers arise with enough flow to host annual kayak competitions – the Breede and the Berg . The Berg flows north- northwest and the Breede flows southeast. In my teens, I canoed both. For diversity of geographic condition, the Breede stands head-and-shoulders above the Berg along those stretches before tidal reaches are encountered. The hill-bounded estuary of the Breede River is a wonderland of life. It is there that I recall making some of the fondest memories of my pre-adult life. There was a guest house there that had rondavels to rent where my parents liked to vacation. You could rent these wooden boats with a little outboard motor and go fishing anywhere along a fifteen mile stretch of the estuary. Once, my stepmother caught an eighty pound kobeljou. Mostly, it was smaller fish. That was then, when I was little more than a pale reflection of what I felt my father wanted me to be. Today, I would never take such a fish out of the water. Some little thing for the pan that evening, yes; but such a fish – a prime adult that had come up there to breed – for no greater reason than to boast about it? Absolutely not! There aren’t words to describe the feeling of being out there on that vast estuary, alone with the wind, the water and the weather. It opened up doors within me that allowed me to grow beyond just being a half-baked reiteration of my father.

Having completed high school, I was obliged to undergo military training. The threat of a pan-African invasion from the north was very real during the years that Apartheid was the order of the land. Insurgents were already probing the northern border.

After the schools I went to, life in the South African Army was a definite step up. It was hard, but it was also a lot more straightforward. If you performed well, and had potential, you would be promoted. Who your parents were cozy with, was utterly immaterial. What they were looking for was simple – physical and mental toughness and smarts. Proficiency with weapons was just icing on the cake. I must have fit the bill, because I was one of only two in my intake to be selected to train the fellows in the next intake of trainees. It was a role I took too well, and the guys I was responsible for liked me. As much as I demanded out of them, I readily commended them for anything well done. The skills of leadership that I learned in the army lent themselves well to heading up a band of musicians.

When I arrived back in Cape Town after basic training in the army, I was neither and adult, nor a boy. It was expected of me that I would attend university and, having secured a degree, become employed in some firm or other. In high school, I had been top of the class for the whole of my final year. The natural expectation, therefore, was that university would be a breeze for me. It didn’t turn out like that. The way the university winnowed down the first year complement of students was to first weed out the slow. We might as well have been attending a stenography training class. Lectures on this and that we’re casually flung at us, with no attempt to really engage, for which lofty offering, we we’re expected to take copious notes, at break-neck speed and then regurgitate the facts in tests given at select intervals during the year. It’s an absurd way to render instruction to those who have paid dearly to be thusly underserved, but hey, it certainly worked to pare down the ranks and shore up the notion that those with degrees are so few in number that companies have to pay big bucks to secure their services.

My right thumb had been smashed at the first joint in field hockey, back in high school. Today, more than fifty years later, it is still misshapen. Back then, writing was sheer agony, but I could function as long as I went rather slowly in manageable bouts. It didn’t take long for me to see where this was going. First came the anxiety, manifesting in the form of horrendous migraines that would leave me prostrate in a dark room for more than a full day at a time, missing lectures. Then I started failing the tests. It was all about the writing, and the writing was on the wall. I would flunk unless I could take notes at the required speed.

I didn’t really want to be an engineer anyway, sitting in some office, day after precious day. What I really wanted was to be a great songwriter. I couldn’t see how you could be a job-holding civil engineer and a working creator of musical content, at the same time. Maybe it’s possible but, at the time, I was strongly motivated to take the plunge into something I could put my heart into and so I chose music, gratefully leaving the lecture halls droning on in my wake.

“I made the right choice for the being that lived inside me”

My parents hated me for it, but I think it was one of the best decisions I ever made. Sure, there were hard times to follow, with respect to money, but think about it: if I’d become a civil engineer – even a rich, successful one, like my cousin, Anton – would you be in any way, interested in what I have to say? Most likely not. Would I be living with this lovely, winsome, earth-centered, American woman, out here in wide-open country in the mountains, tending our giant garden, still making music and looking eagerly forward to bigger and better as a songwriter, among other enterprises? Would a search on Google feature (a version of) me on the first page? Most likely not. Enough said. I made the right choice for the being that lived inside me.

I don’t say this flippantly. Following my own path in life caused me to be unjustly struck from consideration in my father’s will, which sat very badly with me. Not only did I feel incredibly demeaned in the process that unfolded after his death, denied any and all information about facts, or what occurred with his remains or the family homes, but it cost me dearly in terms of the inheritance that I, as his only (and non-offending) son had a right to by birth. Ah well, as I said before, I was only ever an inconvenience to my parents. In the end, with their final act, spared the discomfort of having to say it to my face, they let Nedbank, their wealth management company and estate executor, say it for them.

Having disappointed my parents with my decision to flunk out of UCT, I couldn’t reconcile myself to the thought of continuing to live in the same house as them, which was very much THEIR house and not mine, in any sense. It was time for me to make my own way in the world. I moved out, never to return.

That leaves the part about whether my parents helped my musical development in any way. The answer is that they helped a lot in the early years while we were in our first house on Bertha Avenue, near the Liesbeck River – mostly in providing a music-friendly environment in the only place in all my life that ever ranked as a true home for me. There was a grand piano in the sunken lounge, with windows looking out over the garden toward the eastern buttresses of the Table Mountain massif. My father would play quite difficult pieces on this piano, and when my grandfather came to visit, he would play even more advanced material of a classical nature. For the eldest boy to be schooled in music on the piano was a customary family responsibility that I took to quite well. In the memoir I am writing, I explain the ups and downs of that process. One excellent motivator for me was that my primary school had a music prize, which I quested for and ultimately won.

In those early years, in the smaller home, we were a better family and music played a big role in our lives together. Doubtless, under pressure from my stepmother, who was relentlessly class ambitious, my father undertook to build a new, larger house near the crest of Wynberg Hill, on a lot next to the residence of the American ambassador (my father was the honorary consul for Mexico before Mexico broke with South Africa over the issue of apartheid). Having a second house built was a reach too far, even for him. The pressures placed on him by a multiplicity of responsibilities caused him to become overwrought, which my stepmother sought to address by concocting a subterfuge with the family doctor that ended with him receiving electroshock therapy. The process effectively fried the delicate neuro-circuitry by which the intuitive functions of consciousness influence decision making and emotions in response to realities and potentials encountered. No longer would subtle extraneous influences be allowed to meddle in whatever had to be done. This may have helped them get what they wanted, but it also cut the means whereby the future dimensional self works at the very roots of consciousness to incline emotion toward some objectives and away from others.

In hindsight, I see how what was going on with him was trying to dissuade him from building that new house, because the future self knew that doing so would cause the bonds of family joy to whither away and the paternal side our family line to end.

Apparently, toward the end of my father’s life, playing the piano became a bigger part of his daily routine, even as his mind began to fail, as if he were being moved to reconnect with where things once stood, before the fateful house move.

The lesson here is that it is never a good thing to suppress your intuitive side in an attempt to secure some objective you’ve set your sights on. Stay fluid. Life is a dance, not a march. And keep the music coming, because it’s the nutrition that feeds the structures in your consciousness by which your higher self communicates priceless advice to your mundane self.

When did you begin playing music? What was your first instrument? Who were your major influences?

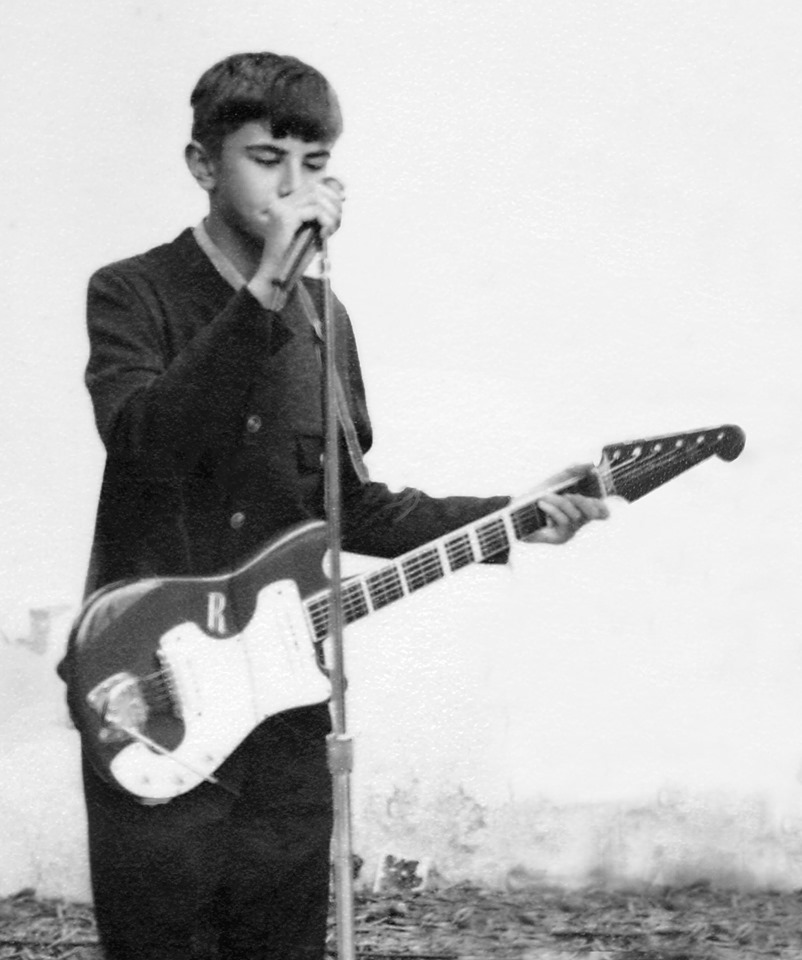

I first started playing music when I started using a musical instrument that people who are not body-centered sometimes tend to overlook as an instrument. I think I was 5, at the time; before I went to preparatory school. No, it wasn’t the piano and it certainly wasn’t the guitar. It was the voice.

Our household not only had a cook, but a maid, as well. Actually, during the course of my very young life, we had several maids. Besides helping with the house chores, their job was to take care of my younger sister and me and see that we didn’t get into some kind of trouble (like falling into the pool, for instance). These maids were all young, colored women – no older than 20. The one who sticks in my mind was called Ethel. I can still see her face. It was round and she had freckles. At that time, the song, “Hey There”, sung by Rosemary Clooney , was a huge hit in South Africa. With encouragement from Ethel, I learned to sing that song. That was my first foray into making music. Though Ethel never got paid a dime for services as a music tutor to me, she did, in fact, lay the cornerstone of what would become my ability to make music.

Later – I can’t remember exactly what age I was, maybe 8 – I commenced taking piano lessons at Western Province Preparatory School, while I was still a day scholar, with the legendary Katie Maritz. Miss Maritz tutored many exceptional pianists in her long career at WPPS (Wet Pups). She was indefatigably patient with her students, even the ones that had hardly any native talent, at all. Every student mattered. The goal, from her point of view, was to induce in each of her students an enthusiasm for whatever level of classical music they could handle. In this quest, she had a formidable ally among the staff – the equally legendary Miss St. Hill, our English teacher, who – though she was diminutive in physical stature – loved the arts with a huge heart and had a voice that could drown out a whole choir (in perfect tune, I should add). I loved studying the piano with Miss Maritz, and I loved studying English literature under Miss St. Hill. Put the two together and you have the makings of an incipient songwriter.

There was another music teacher at Wet Pups, more like a choirmaster – a man whose name, I’m ashamed to say, I can’t remember – who taught us much in the way of songs from the canon of traditional British music. These had survived the test of time as songs that could be sung by present company in everything from pubs to palaces, as a way of stoking the fires of fraternity. It was a joyous aspect of being at that school, (even as a boarder, banished from my home, just down the street). That those who ran the school thought it important enough to preserve the art of group sing-alongs indicates how strong the cultural imprint of colonial times under British rule was at the time.

“What I’m tasked with doing is to think like a listener, to get into the collective mind of those who find themselves resonating in sympathy with what I write”

With respect to influences that might have affected how I developed as a songwriter, you can credit Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann and Mozart as being among the earliest on the classical side. But there were more modern influences, as well. My parents would often play music from modern American shows. In particular, I remember learning to sing all the music from the following: My Fair Lady, Gigi, West Side Story, The Sound of Music. The work of Gilbert and Sullivan also played a big role. I tend to like music that moves at a nice pace from one feeling to another, before I get bored. How brilliant the execution of it happens to be really doesn’t interest me. The world is full of virtuosos, quick to put their videos up on YouTube, as if to say, “Here, beat this!”, which is fine if you’re looking for a novelty moment. I will never be one of those people. That’s not my destiny, or my proper role. What I’m tasked with doing is to think like a listener, to get into the collective mind of those who find themselves resonating in sympathy with what I write. It’s not MY music that I try to coax into being; it’s OURS, already living inside us, waiting ever to find form as something we can take in through our ears. When we hear it, we can feel it coursing, without resistance, through the inner world of our being, hitting all the sweet spots, as it goes, and leaving us feeling a little bit more alive.

Many of those sweet spots were formed by our earliest listening experiences – experiences we shared in common with millions of other people, all around the world. As a group, we share subtle proclivities toward liking this or that kind of song or treatment, regardless of genre. What I’m trying to do is find the right pathway through the jungle of the business side of music so I can deliver my contribution to those who inhabit the same proclivity world as I do.

Part of that challenge involves correctly interpreting the vibrations of that group in the creative and performance aspects of rendering a finished master tape or sound file. The greater part of the challenge lies in subsequently connecting with people in the business side of this field who don’t just have the same taste proclivities, but also have sufficient clout to bring the music to the attention of those who are already inwardly primed to welcome it into their lives.

In summation, I think it’s important to note that I don’t consciously strive to incorporate elements of the music I was raised hearing into the music I write. I write what I hear in my mind while I’m working on a song, that’s it. Just how those early listening experiences tie into how I go about composing isn’t something that I care to dig into too deeply. It would be like eviscerating myself to find out how my stomach worked. I just accept that there’s something in there that is going about its business, and I’m grateful that, so far, it hasn’t let me down.

You were the leader of the band called Wakeford Hart.

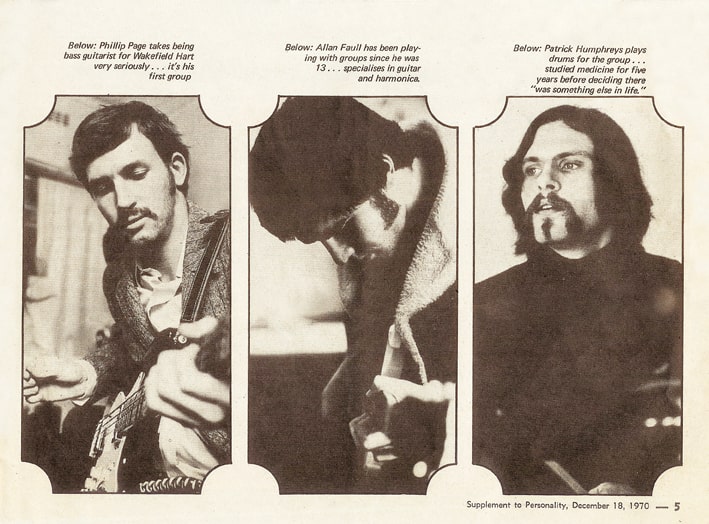

“In the meantime, the band that a few friends and I had started informally began to show promise. Through a friend, I met Allan Faull, who was really good at blues guitar. We clicked together and soon joined up with Patrick Humphreys on drums, Phil Page on electric bass and Phil’s girlfriend Dee French singing backup vocals.

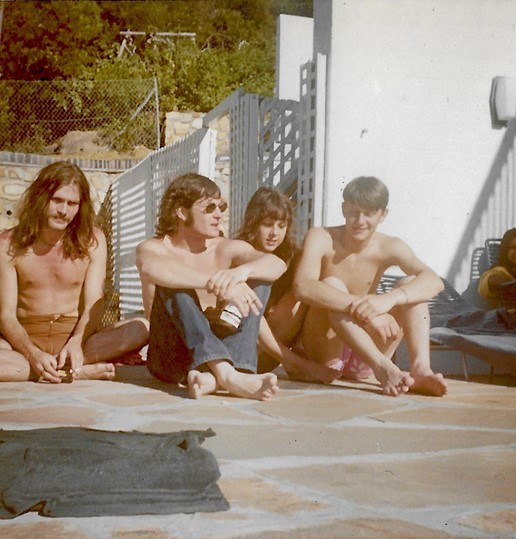

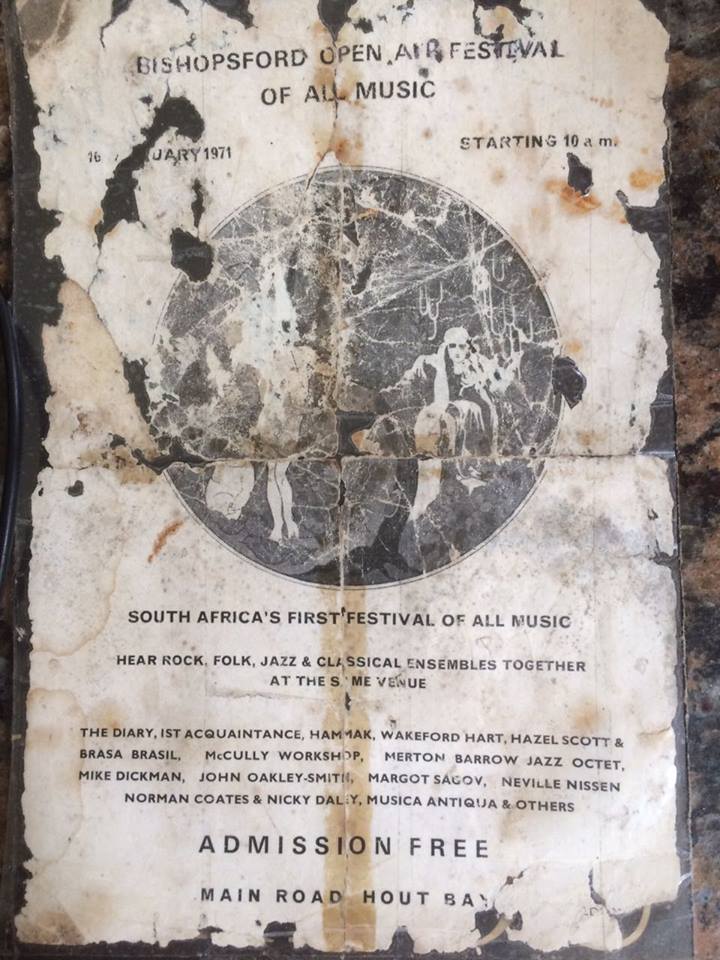

One thing I needed to reflect on so that I could recall it for the purposes of this bio is where we practiced our songs. A band has to practice. In that reflection, I realize how much I depended on Patrick and his wife, Roni for making that possible. They had rented an old farm cottage out in the Hout Bay valley, which they made available to us for getting the band together and working on the material. By some process I can’t remember, though I have a great picture of it, there was a piano to play there – another improbable, but essential asset. This happy collection of elements gave rise to the notion that we might be able to organize an outdoor concert somewhere nearby.

Bands need to have names. It’s always a head-scratcher trying to find just the right name for a band. It needs to evoke a tug of interest in the one who hears it and a feeling of existential fact in the one who says it. Also, it helps to have a good logo. First off, I didn’t want anything that started with “The”. That was too old school for me. I wanted the name to suggest that the band was like a personal friend you could say something to, and get an answer from. Also, I wanted it to be a little bit mysterious; suggestive of something amazing, though not in a declarative or definitive way. Though some bands choose names that associate them with some famous precedent, I didn’t want that. It had to be its own precedent; the first vocalization of some ineffable, eternal concept – something approximating an incantation. In the end, I settled on Wakeford Hart and I guess that choice was a pretty good one, because it has endured the test of time and remains relevant as a memory for those who embraced it back then, though the music has not been played for forty-six years.”

I’d like to add a few words about becoming the leader of the band, Wakeford Hart. There are all kinds of leader. As has been said before, some are born to lead. Others are trained to lead. Some are inspirational. Others are controlling. For me, it was all about just getting things done and giving a voice to the music that was in me and wanted out.

The obvious question is, what gave me the confidence to rise to the challenge of leadership? The answer is relatively simple. It was the trust placed in me by my superiors in the South African Army when they tapped me to be one of only two instructors for the next intake of trainees – a role that I took to naturally and enjoyed. Thank you, guys!

Now this was somewhat ironic. Back in the days of Wet Pups and St. Andrew’s College, I had been totally passed over for consideration as a monitor or prefect in either school, despite a formidable academic record and despite having earned what is referred to in St. Andrew’s as a proficiency tie, plus a Rhodes scholarship commendation. For those who aren’t familiar with the terms, monitor and prefect, these are boys who are given a level of authority in the school that allows them to help retain order and general discipline among the other boys. Apparently, among the staff of both institutions, I was not considered leadership material. At the time, that judgment hurt. Today, having run a company for twelve years and captained my own ship for forty and more, all I can say is, oh well, water under the bridge; shows how much they knew. Just don’t bother to invite me to the the jubilee class reunion.

What influenced the band’s sound?

You know, we really didn’t have the musical chops to copy the playing styles of musicians who were popular at the time and have it come off sounding great. Here we were, in a country with only one official radio station – the South African Broadcasting Corporation – and the only material close to what we wanted to play was the imported hits from the USA and Britain. The situation suited the only record distributor of size in the nation, Teal Records (where I worked for a few months). It meant not having to carry an extensive inventory, with a considerable fraction of titles either selling slowly, or simply not selling ever, along with the tidy advantage of linking the hit parade activity on the SABC with the need to move product. It was a cozy relationship, to be sure.

This process of optimizing sales for Teal demanded they stick to product put out by the best exponents of pop music in the world. We knew that if we played songs that everybody else had heard the best versions of, we might come off looking rather lame. There was another way that we felt had a chance of success; with luck, we could reverse the existing market paradigm by making some kind of original material that could go out to the world if it made a big enough splash within the country. We wouldn’t be the first to do it – Four Jacks and a Jill had already gone global with the hit, “Master Jack”, written by David Marks, so we knew it could be done.

“I’d take anything that lent itself to making me feel good when I heard it and that offered room for some instrumental improvisation”

Key to this grandiose gamble was developing an original sound. For that to happen, I would have to pull it up from within myself and run it by Allan Faull and see how it turned out. We wove the better results into complete songs and kept the not-so-successful ideas in the cooker for subsequent reworking. Nothing was off limits just because it happened to have come from some genre not typically associated with modern pop styles. I’d take anything that lent itself to making me feel good when I heard it and that offered room for some instrumental improvisation. If we could play it, we’d try to use it. At the same time, I wasn’t going to get too lassez faire about it and let the process drift into territory where the songs would lose cohesiveness.

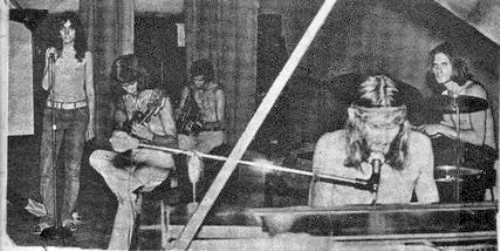

The results of this approach are best heard on the album of the last concert I did. In that instance, I was lucky enough to have assembled the most appropriate collection of musicians, up to that point in time, to try its hand at interpreting what I had been working on. The band may not have been performing under the name, Wakeford Hart, but that was out of consideration to those of the original lineup who were not there and who were staying in Cape Town, not leaving it. The constructional basis of the music remained the same and, in that sense, it differed by only a few degrees from what Wakeford Hart would’ve played.

It’s a point worth making that though the external aspects of Wakeford Hart remained behind in South Africa, the spirit of it, and the intellectual property thereof, and therefore, the sound, remained within the consciousness of the mind that travelled across the Atlantic to South America, and thence, across Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador and Colombia to the USA, in an effort to circumvent the obstacles arrayed against it in South Africa, back in those days.

I resist the idea that Wakeford Hart is nothing more than a a flash in the pan of the history of popular music in South Africa, now dead and buried. It’s much more abstract than that. It’s a reminder that persists to this day, in the minds of many who yet live, of how we yearned for better – and how we still yearn – and will only fully disappear when those hopes and dreams are fully realized and all of those who were inspired by the aspirations it sought to serve are dead and forgotten. Thanks to that one record I managed to put out and an old master tape that sat on a shelf in a basement for forty years, they now include more people than back in 1972 and even some who were not yet born, at the time, not just in South Africa, but all over the world.

Is this something I envisioned, back when were just a bunch of young people knocking about a few musical ideas in Patrick’s house? Honestly, if the idea had found lips to express it among ourselves, we would’ve laughed out loud at the absurdity of it.

What kind of material did you play? How would you described the sound of Wakeford Hart? How did you decide to use the name “Wakeford Hart”?

The song material I wrote had to cover three main bases: one, it had to have a good theme, expressed in the best lyrics I could concoct; two, it had to ride on a pleasing set of chord changes, so as not to be boring; three, it had to have a good melodic structure that could be sung not just by the band, but also by those who had heard us more than just once or twice. My approach to the instrumental material was a bit looser. Whether it had this feel or that feel wasn’t important. We were not a genre-confined group.

One can see, in an instant, how this approach would not fit smoothly into the way recorded music was being marketed at the time. That was the down side of the equation. The up side of the equation is that, if you do mange to break through to having an extensive listener ship, you can feature a wider array of music, appealing to a more diverse fan base and thereby counter the risk of becoming pigeon-holed. No one has managed to pull off this trick more successfully than the Beatles, though others have used it, for obvious reasons.

This approach is completely opposed to that of using bass and drums as the lead component to the making of a song and assigns those instruments to a supporting role, rather than being out in front of the composition. My chief concern was that the lyrics and melody not be obscured by percussion and bass during performances.

The resulting relatively quieter sound worked quite well for concerts. It could have been even better if I had had the good sense to make a dedicated sound man part of the band. The sound man’s familiarity with the material can make all the difference to the way a band’s work comes across to an audience. One of the worst mistakes ad hoc sound men make is that of thinking that volume adds value to the listening experience. It doesn’t. All it does for most people is switch the brain to ear-protection mode, which makes you tire more quickly and want to go home.

As to why we chose to use Wakeford Hart as opposed to other options, I’ve discussed that already, but could add that there’s a lot of mystery behind the selection of a name. It just has to feel right. You run through countless options. Gradually, one begins to feel more real than the others. This is the name that connects you most directly with the collective will of the aggregate, collective Future Self, which includes all of those for whom the experience of that named collective will be significant.

People with the knack of picking great names out of the ether are de facto futurists. If I were one, I’d have bought stock in Amazon when friends of ours in Seattle were working to build it from scratch, and be rich today. In fact, I was averse to the whole idea, in view of the damage I thought it could do to main street merchants in the book and music trades. Now, I use Amazon to make up for the absence of that kind of shop out where we live. With respect to choosing Wakeford Hart for a name, however, I think it was so close to my personal destiny that getting it at least part right was a lot easier.

What happened after the band stopped? I read that you gathered a new group of musicians to help you perform.

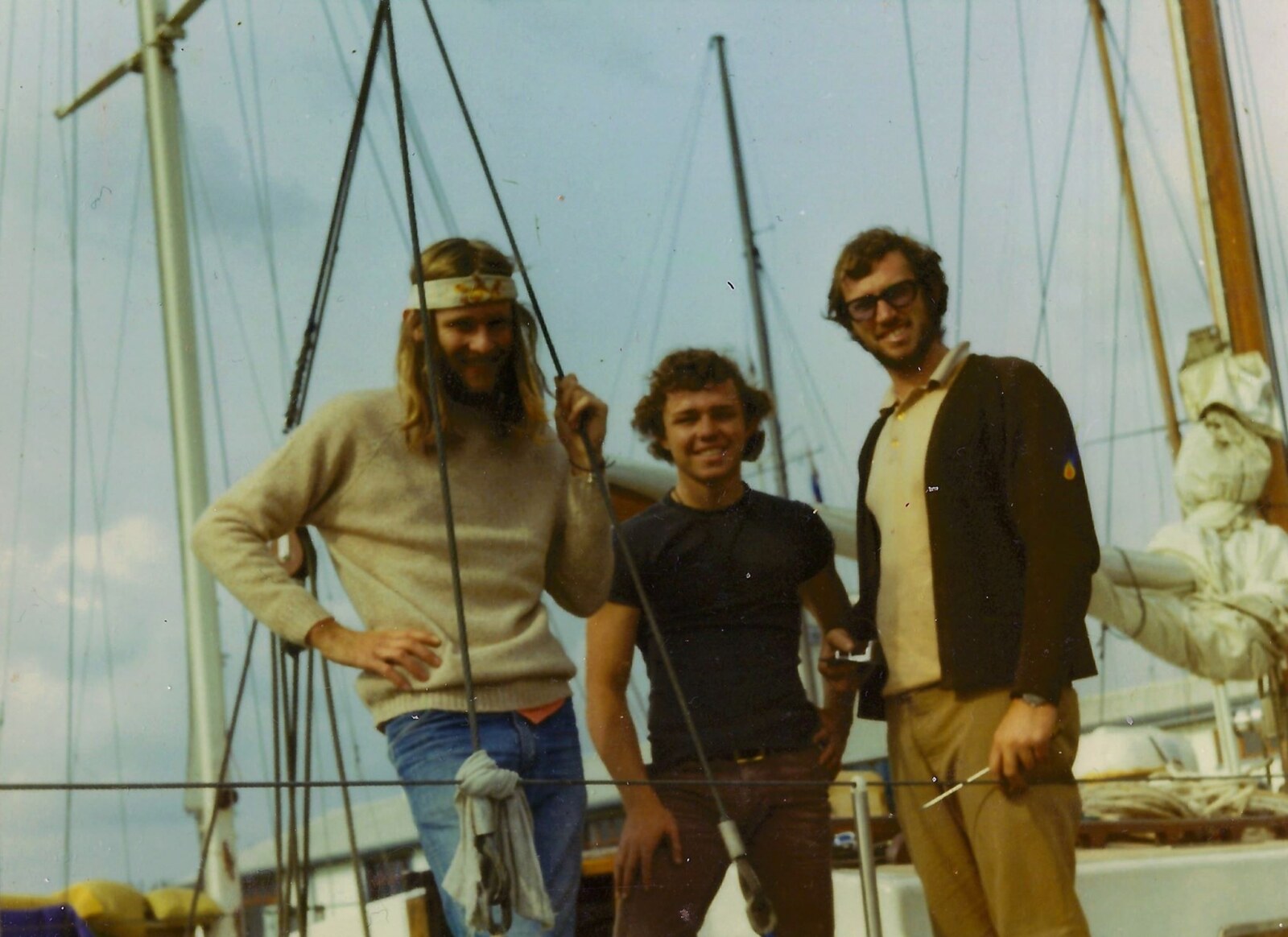

This is a bit of a difficult question to delve into. It involves a terrible thing that occurred a little past midnight on the thirteenth day of June, 1971 – exactly one year, to the day, before the yacht, Wayfarer, put out into the Atlantic, under a leaden sky, bound for Rio de Janeiro, with me, and a crew of four others on board.

We had been hired to play at a very big party out in Kuilsriver, a suburb to the west of Cape Town that used to be farmland. At the time, the lineup in the band included (if I remember correctly), Allan on guitar, Jacque de Villiers on bass, Patrick on drums, Amanda singing and me doing my thing on piano, guitar and voice. It was an ill-chosen decision to play and, from my recollection of it, did nothing to boost the reputation of the band. The hosts had decided to lay on a good time for their guests and there were over a hundred people there. Part of the offerings was a performance by a fire-eater whose show consisted of choreography around a bowl of burning light oil perched on a stand, using flaming batons to execute intricate moves that made interesting patterns in the dark. It’s an ancient art that requires great precision to pull off. There were long benches arrayed around the performance, for the greater benefit and enjoyment of spectators. To offset the possibility of rain making the show impossible – it was, after all, midwinter in Cape Town, when rain falls there – the performance was held in a great big barn.

When the performance commenced, I don’t know why, but I stepped outside. The whole thing seemed a little risky and it was too crowded in there for me. My back was turned to the barn when, suddenly, there was a huge bang and people screaming coming from inside the barn. I got a big fright. People came running out of the entrance as fast as they could go, flying by as I stood there for a few seconds, wondering what to do. Perhaps it was the army training that helped me keep my head, but as soon as the entrance cleared, I entered the barn, to see what the situation was.

There was fire on the floor, and smoke thick in the air. There was no one left in the barn, save one. In the gloomy half-light of the flames, I could see the bench that the crowd had knocked over, from whence the bang had come, and standing a few feet off to the side, a girl so badly burned that flaps of skin were hanging off her arms and face. Despite the horrible disfigurement, I recognized, to my horror, that it was Jane, our road manager, Charles’, girlfriend and helper. In that instant, I knew that if I did not do the right thing immediately, she would die, and in that instant, the right course of action came to my mind: first, not to touch any part where she was burnt, and use my voice only in an attempt to get her to use her own will to stop her system from going into shock, which, I was sure, would kill her. As gently as I could, I fixed her attention on my voice, telling her that it was vital for her to calm down as much as she could and concentrate her will on surviving. Into her will, I let my own flow. Somehow, we got out of there, and I stayed with her outside, as she stood there, trembling, talking up her will while the others scrambled to get ready the van we had come in, to take her to Groote Schuur, a hospital with one of Africa’s most experienced and competent burn units. Patrick stayed with her in the back of the van while Charles drove. In a smaller town, the hospital would not have had an all-night staff, but this facility went round the clock, and so they were able to stabilize her immediately.

Jane did not die, but she came close to it, with months spent recuperating in the hospital and a seemingly endless series of painful skin grafts to endure, at the hands of a surgeon for whom the agony of others had become routine and unspectacular. Despite the spiritual trauma of it, the experience did not succeed in crushing her. In fact, though I would wait for forty-four years to discover it, it actually helped her make an exceedingly strong-willed and compelling person of herself.

Later, we learned how the incident had happened. Some idiotic reprobate had indulged his male sense of mischief by kicking over the stand on which the urn of burning oil sat. The blazing liquid went straight under where Jane was standing, enveloping her in flames. She just happened to be standing in the wrong spot for her luck (but maybe the right one for her destiny; it’s hard to say).

In a shameful indictment of the indifference of Cape Town’s “finest”, the perpetrator was never pursued, publicly identified or called to account in a court of law.

For me, the experience left a cloud from which I could not recover – the feeling that if that young girl hadn’t been there, chipping in to help in the logistic side of Wakeford Hart, she would not have been injured like that. After I left Cape Town for Rio, everything happening back in South Africa became unknown to me, but the share of responsibility for what had happened to Jane lived on in my conscience.

Up to that point, I’d felt that my music-related efforts were blessed. After that incident, I felt exactly the opposite – that they were cursed. It’s the sort of thing that burrows down into your consciousness and then metastasizes, insinuating doubt into everything you do, like a worm in an apple. You want, somehow, to repair the damage, but there is no way you can.

Another bad thing came out of this incident. After it happened, I approached my millionaire father to see if there was any help he could render, either to help Jane’s family with expenses, or put pressure on the police to arrest the perpetrator. He showed no interest in the incident and declined to become involved. I was ashamed by his unwillingness to do anything to help. It left me wondering just what kind of person this man I called my father really was. Did he have a heart, or was he just so mentally based that nothing could so move his sense of empathy that he would be willing to part with a single dime to assuage it? I got the definitive answer to that question when I was left disinherited by him in 2015.

2015 was also the year that I was released from the burden of thinking that I was surely resented by Jane Parkin for what being involved with Wakeford Hart had done to her.

2015 was not a good year for Rachel and me.The difficulties that we had experienced living in this tiny, feud-stricken town had reached a climax. We were being targeted by people who were convinced that we were communist operatives, working to advance an insidious plot by the Obama family, and others, to impose One-World-Order restrictions upon the county, most notably, gun control. It sounds laughable, but at the time, it certainly wasn’t. When a photoshopped picture of the President hanging from a noose was posted on the windshield of our car, it gave me the perfect opportunity to push back. We sent the image in a letter to the secret service and left the rest to unfold as it would, and as it did. From that point on, people left us alone. But we were bummed out that this was where we were stuck.

I knew a bit about incantations – the result of deep immersion in the field of metaphysical writings back around 1990. I knew I could make them work. I also knew enough about them to be extremely cautious around that kind of forming instrument. But we had reached bottom and it was time to call in the Good, even if the Bad had to make way for it.

At midnight, in a howling gale coming down off the mountain, I walked into the middle of the only highway intersection in town and opened a channel into the future, with a special combination of ancient words used by gnostics for millenia. This should alarm no one. Prayers are supposed to work in the same manner. I made a request for good things to come to us from anywhere on the planet and then closed the connection – the same function that saying “amen” at the end of a prayer performs.

Over the course of the next week, we received three introductory emails from people far away. One was from a music producer in Sweden, regarding possible collaboration on mastering a song, one from a radio reporter in Berkley, California, regarding an in-person interview, and the last one was from Jane to Rachel, enquiring whether she knew of a way to get hold of me. I tried to find that initial email from Jane on our Yahoo account, but the log backward ends a few weeks after that happened. Basically, it said that she was looking for Peter Wale who, forty-four years earlier had saved her life. It was so out of the blue that I was almost in a state of shock about it. It started a remarkable series of emails back and forth in which I learned of the various challenges and triumphs of her journey from near fatally burned Capetonian girl to a strong-willed, but still-unsettled woman with exceptional writing skills, bravely beginning a new life based in Portugal (the visiting of which, by Rachel and me, depends greatly on how well the record reissue of The Memoirs of Hakeford Wart is received in Europe). Given what I now know about her, she has a compelling autobiography of her own quietly percolating up to the surface of reality.

One startling fact that emerged from our revived connection was that she was still a Wakeford Hart fan and that she knew of other fans. It was only then that I began to realize that the name didn’t just pertain to a band of musicians; it was more like a thread of common identity that still connected many folks, in countries all around the world, to one another – invisibly but enduringly. I should have known it before but, you know, I was so immersed in my American survival experience that I was absolutely oblivious to it. This apotheosis lifted a burden from my shoulders.

Back in 1971, all I could see was that the band thing wasn’t happening after the fire incident. But now I was known as someone who could write music and I was approached to do work for other people’s projects, independent of the band. This work served as a bridge to performing under my own name.

One project worth noting is the music I wrote (on short order, I might add) for the satire, “Tom Thumb”, written by Henry Fielding and published in 1730. It was a clever little reworking of the original farce that could have been a big success in, say London or New York, where you don’t have to be literal to amuse people. But it was put on in Cape Town, which, though beautiful, is not overly predisposed toward copping to the sardonic reworking of old English masterworks, designed to drill little holes in the comfortable assumptions of the privileged and – more than that – get them to laugh about it. Plus, there was the distinct fingerprint of the Nationalist government on the sudden cancellation of the production at the Nico Malan Center, after we’d given only a few performances. There was no appetite in the existing regime for tolerance toward artistic expressions of dissent, however oblique.

To flesh out whatever I could come up with in so short a time, I had the help of a fellow who could play flute and saxophone like the devil. His name was Sean Bergin. Some years later, I was surprised and delighted to run into him in New York. Though Sean died in 2012, he lives on in the annals of both American and South African music, principally as a gifted jazz player, rich in the influences of South African musics. The fact that he was born only five months before me, to the day, and now is six years gone, does not escape me. It’s a wake-up call reminding me that our days are numbered and there is still a lot of good music to be recorded. Perhaps Sean’s immersion in his craft was too intense. Having worked with him, I know that there is a distinct possibility of that having happened. For my part, I am just grateful to still be here and looking forward to working up new and better music with Rachel.

Creatively, “Tom Thumb” was pretty good work; but when the rubber hit the road, it was an embarrassing flop that I did not take lightly. Suddenly, Cape Town seemed like a provincial dead end for me, and when the chance to join a crew sailing to Brazil on a yacht came up in late 1971, I applied. The actual date of departure was to be in mid 1972. My enthusiasm had been stoked by my natural mother’s new husband, Carlos Cotrim, whom I had met for the first time in the first half of that year. He was an urbane, worldly, Brazilian man. They had met in Germany at a time in my mother’s life when things weren’t looking up for her. They had left Germany and come to South Africa for what would turn out to be two year sojourn, before moving on, for good, to Brazil. He made a big impression on me, with his descriptions of life and music in Brazil (some of which, I was to discover, were somewhat exaggerated, or out of date, when I got there. No matter.) Sitting there in the living room of their house in Johannesburg, during one of Wakeford Hart’s most unfortunate forays out of Cape Town, listening to him talk while we all drank gin and tonics in the heat of early evening, remains one of my most delicious memories ever. That I should so soon thereafter be given the opportunity to act on the visions he had planted in my mind is just one more of the entirely improbable events that occurred at the time.

By the time the old year was giving way to 1972, I had put so much into the music thing, with so little to show for it that home, for me, had become a one room shack, on the poor side of the tracks in Mowbray. There was no bathroom and my bed was a pile of straw. The contrast between these circumstances and those of my parents, only four miles away, up on Wynberg Hill, could not have been starker. But I never even stopped to think about it. I had become a social nomad. Mostly, I spent the nights with whatever girlfriend would have me stay over, which may seem outrageous in today’s world, but wasn’t that unusual back then. Of girlfriends eager to play host, I had a greater share than people these days might deem politically correct. But I was good looking, earnest and well known as a musician among people my age, so, as long as I amused those who valued my presence, it was a viable option for someone in my position to be exercising. I had given my all to music and music, in turn, presented me with an unconventional way to survive.

This was the background circumstance of my life when I threw myself into the task of putting on a farewell concert. To deny that I was in any way angry at how things had turned out for me would be disingenuous. At 23, standing at the start line of adult life, you tend to be extremely prone to subjectively driven thinking and behavior. Your ego is very strong at that age. Emotions rise quickly when things get in your way. Losing is not taken with equanimity. This leads to choices that others may find objectionable, and that’s the down side of young men, such as I was, at that time. On the other hand, even if you are a bit of a pain in the ass, you tend to get more done at that age. There is a never-ending battle being played out between the viewpoint of the young and that of the old. Thankfully, the old take their convictions to the grave with them, while the young take theirs into the prime years of their lives. And so, society tends to leave things that no longer serve well behind.

While I was, indeed, an angry young man in 1972, I also had the good sense to realize that I would have to be as clever as I could manage in expressing it through music. Today, you can say anything in a song, and still get some kind of audience to go along with it, but back then, you had to be subtler about it.

Taking it right to the edge was what I had in mind, and what I did. After all, I was leaving Cape Town and would soon be forgotten, but maybe some of what I had to stay would stick and contribute to the change I knew had to come some day.

How I got those young people to play had everything to do with the fact that I would be leaving; like a parting favor, if you will. They also got paid – both for practice time and off the take from ticket sales. Friendship, I’m sad to say, had little to do with it: not one ever bothered to stay in touch after I left. The music world, for all its pretensions, is not full of deep brotherly love. It’s about competition and getting ahead and making a living. It’s more a business than a fraternity; it’s about comparative skills rather than camaraderie and about personal advantage rather than personal amity. Warm and enduring relations are more likely to be cultivated with those who’ve come to listen than those who come to play with you. In that sense, it’s a realm full of professional promiscuity, particularly here in the northwest of America, though not exclusive to it.

It took me a long time to learn to accept this, and when I did, it saddened me. What I had in mind when Wakeford Hart began was something warmer, kinder, more inclusive and far more resilient. No doubt, there were others who copped to these sentiments and held them in their hearts over the passing years, particularly those who owned and valued one of those records I put out on the eve of my departure. If you’re reading this, and happen to be one, be assured, you’re a special person. I hope this serves to add value to what you have.

On a more encouraging note, I have to add that I was contacted by Patrick Humphreys not long ago and we agreed that a reunion concert in Cape Town would be a gas, if it could be arranged. Also, we had the wonderful visit from Amanda Blue Leigh in the spring of 2016. So, you know, there’s always the chance that something special might be cooking in the kitchen of Divine Providence.

In 1972 you gave a concert with your group. Handful of tracks from the performance was selected and you pressed 300 copies. Would you share your insight on the albums’ tracks?

As you may know from what Strawberry Rain has announced on Facebook, there were 14 songs performed at the final concert. Actually, there were 15, but I guess the recording of one song wasn’t good enough. After going through what we had, I decided on four tracks. The challenge I faced was how best to use the track length available on the vinyl disc, while losing as little of the edgy content I had sought to put out in the show.

The song that I had written for the show – the one that encapsulated my feelings and thoughts regarding the limitations facing me and other musicians in Cape Town who weren’t doing the conventionally accepted styles of music played by the SABC – had to be on the album or it would have no statement to make. Next, I really liked the way the opening song of the evening, “C minor Drive”, came out and I’m really glad it now heads up the 3 LP set, but I wanted to feature a lot more of Nicholas Pike’s flute playing (phenomenal improvisation for someone seventeen years old), and since it had to be one or the other, I opted for “One Quiet Sultry Sunday”, in no small way because it said so much about what was happening (and would continue to happen) to Cape Town’s natural environment. So that was it for having a long song on either side. That left space for a shorter track on each of the sides.

The two that fit best were “Rabbit Row” and “Sister Mary”. The former song lampoons the government for advocating that whites increase their birth rate to at least five children per white woman over the course of her fertile years, as a means of counteracting the low percentile of whites in the nation’s population and building up the supply of young white soldiers that would be needed to repel an alliance of nations from the north, intent on destroying Apartheid. My main concern with that policy was its potential impact upon a fragile, thirsty land, already struggling to keep water in its few rivers that still ran year round, and what would happen to the fish that lived in them and the birds that lived on them. “Sister Mary”, the other song, doesn’t just hint at my sympathies regarding the conflict between the mandates of organized religion and the mandates of Mother Nature, when it comes to how men and women go about enjoying the potentials that the difference between them offers; it also reflects my anger that the churches in South Africa provided cover for the schools they inhabited, like the ones I’d been in, for boys to be beaten with the cane, not just for disciplinary problems, but also, for missing mandatory chapel attendance (in St. Andrew’s the punishment was six cuts – a truly depraved act of sadistic abuse, every bit as bad as torture). Need I add that such things were being done to other people’s children, and yet, the churches present in those schools watched and said nothing, and nor did the parents who kept their children in such schools – parents like my own, for instance.

I guess you can tell that I’m not a great fan of organized religion or parents who turn their backs when harm comes to their children because of the hold that prevailing convention has over how they think. I guess you can also tell how, with the choice of tracks for this album, I was taking a few pointed jabs at not just the system I grew up in, but also those who supported it with their unquestioning obedience and defense of it.

One item I do not like hearing on “Goodbye Cape Town (and good riddance)” is my jab at Amanda Cohen for abandoning Wakeford Hart and going with the more musically accomplished band, HAMMAK. I regret that, but I would never take it out of the record. This isn’t some alabaster cameo, wrought perfect. You get the rough with the smooth. It’s the product of a brash young man, blundering through a tough time in his life, with scores of one kind to settle (and scores of another kind to write). On the good side of it, however, would I ever have bothered to put together those particular lyrics about someone whose love and respect I did not value deeply?

Did I feel slighted? Obviously, I did. Did I miss her? You bet I did.

People who love one another are notorious for quarreling over stuff that seems to make no sense to others. Most of the time, they make up, and though Amanda and I have never directly discussed the matter, I think she is old and wise enough by this point to realize that I did her no long term harm by having a rant at her on this record. At least, that’s what I hope she thinks.

Between then and now, we’ve both had ups and downs by the dozen and we’re still connected enough to one another for her to have made the effort to take detour from an event in Ashland, 360 miles away, to come and hang out with us for a couple of days. It was the best visit you can imagine.

Take the whole picture into account and you get an inkling of the lingering effects of the spirit of Wakeford Hart.

Where did you press the LP?

This is an easy one. I don’t know, but somebody reading this may just know.

All I can say is, thank God there was someone in Cape who had a business where a nobody like me could have record like this put together, jacket and all, for a very modest sum.

Having had my own custom window and door company in Seattle for twelve hard years – an effort that cost me dearly and seriously affected my health – I have an abiding admiration for those who put together and maintain small businesses. They are the undergirding for all kinds of other private enterprise that depends upon what they can do. In those days, they were spread out across the developed world, in many different economic zones that were relatively insulated from one another. If one failed, the sector it belonged to was not threatened. There would be the same kind of business in another town, not too far away.

Today, the situation is quite different. Great big companies, having driven small business people into giving up, now purport to be offering the same services once dominated by small companies, like the record press and compiler I worked with. Even if that were true – which it is only in a qualified way – when these big companies fail, or are broken up and sold off, piecemeal, to benefit major shareholders, whole sectors of expertise go down and disappear with them.

One sector that has been affected precisely in this way is the business of producing vinyl records, especially in the USA and Britain. It’s the reason this record, “The Memoirs of Hakeford Wart” has been stalled in the works of Strawberry Rain for more than half a decade. Jason Connoy has a description on Facebook of how the battle went to be able to secure the services of companies that could press the LPs and make the boxes.

Back in 1971, in Cape Town, the whole process for the original item took about a month to complete.

What’s the songwriting process like for you?

Ah, the quintessential question: “How do you go about writing songs”?

If I told you, I’d have to kill you. Sorry, bad joke. No, I’m happy to share.

The fact is that I have no set approach to how I go about writing a song. The real answer is, “Any way that comes to me”. Not joking.

One of my best songs ever, “These Things are You”, came to me out in the orchards, over the course of a few weeks, while I was working as an apple picker in Michigan on the farm of Randy Kober. The lyrics to another excellent anecdotal song, “The Odyssey and the Ecstacy of Paul” were all put together in the shower in our house in Seattle and relayed to Rachel as she stood on the other side of the curtain with pen and pad in hand.

The fact is that, once I’ve begun on a song, I can’t let the thing go lightly. Either the melodic structure, or the lyrics will be running around in my head all day, in a process of constant revision, as I try to discover how the entity in question wishes to be expressed in the physical world.

Quite honestly, I never pay the slightest attention to whether a song might be commercially viable, or not. When I read somewhere that someone thinks they have the key to good songwriting, I take a pass. Been there, done that, don’t agree. All you have to do is look at Billboard’s annals of blockbuster hits over the years and you realize that there is no formula. And that’s a wonderful thing. The public’s appetite for song is staggeringly broad, totally unpredictable and cannot be pinned down, despite the ardent attempts of record company executives to do so. As a result, we always have new and exciting things either breaking through – or taking an end run around – the impediments placed on the creative side of the business.

If you’re a songwriter or composer, the best you can do is to stick to what feels right to you. Don’t let extraneous crap lead you astray. The odds are that you will never be hugely successful and famous, anyway. For you to be happy doing what you do, you shouldn’t let that reality discourage you from giving a voice to the sounds that live inside you. Besides, fame always brings an excess of attention that you have to deal with, some of it uninvited, along with whatever good stuff you might have been seeking in trying to become famous. With respect to writing music, I believe you’re best off regarding fame as something completely incidental to how you approach your craft.

Sure, we all need money to avoid ending up in a bad way, but it helps to keep in mind that getting much more money than is needed to be reasonably secure, to the extent that it begins to attract the attention of people who want to make money with your money, can be a real headache. All you have to do to be convinced of this is read up about the last chapter of Elvis Presley’s life.

So no, I don’t try to make what I’m working on sound like this or that band in the public eye, even if that is what the gate keeping side of the business keeps saying they want songwriters to do.

Once I’ve got the basis of something appealing down, I will play through it as best I can. Depending on the complexity of the piece, just that part alone can take a long time – even decades, believe it, or not. As I said, I’m not an gifted instrumentalist, just one striving to become better, whose efforts occasionally reach a point where everything seems to be just as it wants to be.

But that extended period of trying to get a piece right may, itself, be some kind of advantage in that it offers a greater window of opportunity in which to discover places where the piece might benefit from alterations, additions, removals and rearrangement of its constituent parts. In addition, at some point, I might feel like moving to a lower or higher key which, on the piano, can feel like going back to square one.

These processes of gradual approximation toward an optimal point of arrangement are applied equally to both the melodic aspect of the piece and the lyric aspect of the piece. Everything is open for incremental improvement, and with different melody lines all going simultaneously in the left hand, the right hand and the voice, there’s a lot of work to do before the piece can be inculcated into one’s consciousness in the form known to musicians as muscle memory. Once you have the muscle memory part down pat, you can move on to expression and stage projection. There’s nothing novel about the process; entertainers have been doing it for centuries. This approach, however, does differ quite markedly from the more dynamic, take-it-as-it-comes approach of improvisation typical of jazz and blues players. It is somewhat rare to find people who are proficient at writing the way I do, and also very good at improvising, like Diana Krall, for instance (not that I think I can hold a candle her, or ever will, which is okay by me as long as people who hear what I do get something worthwhile out of it).

Actually, once you reach a certain level of comfort with a piece, and you’ve been through each segment of it hundreds – perhaps thousands – of times over, there’s always some quotient of in-the-moment improvising. Each rendition is, therefore, to some extent, an act of ad lib songwriting that depends greatly upon the context you find yourself in and what kind of mood you’re in and who’s listening to you play. If you happen to feel pretty comfortable and secure, you can get some nice departures from the norm that liven the result up a lot.

Lately, I’ve been really working hard to integrate the vocal and instrumental aspects of pieces, so that all participating instruments get a chance to come forward during the playing of them, and incorporating more interesting modulations of the central theme into the overall structure of pieces. When you’re playing live with your friends, this gives them a moment to be the focus of attention, which I like very much. As such, the songs I’m writing can be much longer and more fleshed out than the norm that has been established by the mainstream of the recording and radio industries. With the exception of a period of greater expressive freedom in popular music during what is known broadly as the psychedelic era, record executives have looked askance at this type of songwriting, to the detriment of the industry, in general, which young people, with their phones, are now bypassing in droves.

I realize that while I was describing the above process, I was visualizing sitting at the piano. The process when using the guitar is a little simpler, because the action of the right hand is simpler. When it comes to playing an accompaniment for a song on the guitar, most of the work is done by the fingers of the left hand and, therefore, the other side of one’s brain from the piano. Switching back and forth, which I do in live performances, can be tricky to pull off.

Whether I use the piano or the guitar for the purpose of writing a song, depends on the feel I want the song to have and where I envision playing it when it’s ready to be heard (you can’t take a piano on a road trip, but you can take a guitar).

With respect to the subject matter dealt with in the lyrics, I tend to look to my own personal experiences for inspiration. I think it lends authenticity to the listening experience when a song is performed by the person who wrote it. That’s why I think you need to have a rich trove of down-and-dirty life experience, through thick and thin, in and out of love, to draw from if you want to be taken seriously, as the author of the content in lyrics. The back story behind the creation of a song can be as important to the creation of the public’s interest as the song itself.

As if the complexity of the process I’ve described above were not enough, by the time you’ve got to this point, you are still far short of doing full justice to a song. Sure, you can go out to some open mike somewhere and do your thing, after waiting all night for sixteen other aspirants to do their thing – and we know how that goes: basically nowhere – or you can accept that you’re only at first base and that, for the song to achieve its full potential, you’re going to have to work on the arrangement elements of the song, which may mean recruiting some outside assistance on some different instruments, before you try the song out on an audience of some kind.

Fortunately for me, I have the excellent collaboration skills of Rachel to draw on, in putting flesh on the bones of a piece. She transcribes the lines I come up with to standard notation on paper, to be played either on one of her recorders, or on the accordion. If she is playing the piano on a particular piece, she writes out her part in full. That happens on some songs in which I play guitar.

So, basically, that’s the mechanical aspect of the job. Most of the rest is learning to play what we’ve worked on with verve and feeling, by basically forgetting any of the hundreds of blind leads we tested putting the piece together and remembering only the options we selected.

What was the political situation in South Africa back in the 1970s? Your music reflects a certain protest.

The first thing you have to understand about the political situation in South Africa at the time is the three main historical roots of the deep insecurities that provided sufficient rationale for the Afrikaner-dominated National Party to push through the many increments of law that became known as Apartheid. The English translation of that word is separate existence. People living outside South Africa puzzle over why it should have been the Afrikaners, rather than the English-speaking South Africans who ushered these laws into existence. They focus too much on race.

The first root was, undoubtedly, that natural insecurity that so easily arises between people who look different and who don’t have the mitigating influence of immersion in a common sophisticated culture that trumps racial tension.

The second root was the intractable suspicion that Afrikaners had developed of the English speakers over the course of 160 years of hostile relations in South Africa, beginning with the British seizure of the Cape in 1806, as a means of preventing the French, under Napoleon, from threatening British colonies in the East. In response, to unsettled conditions, the British found themselves increasingly obliged to undertake military and police actions, including the freeing of all nonwhite slaves in 1828, most of whom were owned by people of Dutch descent who engaged primarily in the raising of cattle and sheep, and the growing of whatever crops the land could sustain, mainly in the interior reaches of the Cape Colony. These people called themselves Boers. In an effort to get as far away from the overlordship of the British as they could, they undertook what is known as the Great Trek, hauling everything they had in wagons, away from the reach of British rule and ever northward into territories occupied by Nguni Bantu people who, themselves, we’re being displaced southward by tribes to the north. Out of necessity, in order to survive annihilation, Afrikaners became formidable fighters, eventually taking on – and nearly beating – the British army in a war spanning 1899 to 1902, known as the Boer War. Defeated, but not subjugated, the Boers turned to politics to gain what armed conflict could not, eventually rising to power in 1948 and remaining there for the next forty-six years. Over this period the National Party explored and tapped out the potentials of apartheid, proving conclusively that their opposition to the liberal aspirations of the English speakers in the country, in the wake of World War II, represented by the United Party, was a fool’s errand that cost the country – and themselves – dearly. The thread that runs throughout this story is the irreconcilable hostility held by Afrikaners toward English speaking South Africans, like me, for instance. Interestingly, we English speakers do not return such hostility in kind. Basically, we have no axe to grind with them. Innumerable aspects of Afrikaner culture are part of our identity as South Africans – part of what makes us distinct among the English-speaking peoples of the world, and recognizable wherever we go.

The third root of the political situation in South Africa pertained to the enormous mineral wealth of the nation that led quite rapidly to a mind boggling aggregation of wealth in the hands of a very small percentage of the overall population, to the detriment of social wealth in the country and, I believe, the prospects for transforming the country into a vibrant and healthy democracy. As has been shown repeatedly around the world, highly dichotomized societies lend themselves to the ascent of demagogues, who rarely help to improve conditions for the poor, especially if the rich don’t care to play ball. There was so much hope back in 1994, with the election of Nelson Mandela, that those who had been shut out of a sharing of the country’s wealth would, at last, have the weight of crushing relative poverty taken off their shoulders. Twenty-four years later, the divisions between the fabulously rich and the miserably poor still remain, but the color of the faces of those who occupy those vastly divergent stations in society have changed. The new rich are not exclusively white and the new poor not exclusively black and brown, but even if the linkage between race and wealth has changed, the general mechanics of exclusivity and exclusion roll on, just as they did back in 1972, when I left.

The ironic upside of the tremendous concentration of wealth in the hands of white speakers of English is that it confounded the attempts of Afrikaner radicals who pushed for making Afrikaans the only official language of the country – a move which would have virtually severed South Africa’s connection to the wider world of English-based business and entertainment, including that genre of music that I, and other English-speaking South African artists, have attempted to add to, with limited success.

Putting all of the above into the time window around 1970, you can more easily see why the Afrikaans based government might have been less than friendly towards the kind of content I was using in the concerts I arranged. Critics, including artists, who stuck out too much might, and did, find themselves under house detention that could be renewed every 180 days. Such action did not come after a warning or a trial; it was arbitrary and immediate. The whole point of it was to quietly send shock and fear into the ranks of associates and, in that sense, it succeeded well, as an example of relatively soft, but pervasive, power over liberal expression.

Of course, the option of house arrest depended quite a bit on there being such a house in which a person could be held. Most of those so confined were upscale, English-speaking liberals. At the time of my final concert, I had no fixed address, which, in hindsight, may have been a good thing for me.

I don’t want to make it seem like I’m a great sympathizer with people of some other degree of pigmentation. All I care about is the advancement of social conditions that make it easier for the average person to exercise his or her inner potential, with the minimum of unfairness to have to deal with. The persons I refer to come in untold variations of outer form. As long as structures exist to make that difficult, I think we have a responsibility to look for ways to modify those structures with as little social disruption as can be arranged. Nothing more dramatic than that.

Back in 1972, I wasn’t so clear about all of this as I am today. I must admit that I saw something of purely personal interest in being seen as a critic of the establishment. It added cache to my artistic persona. Besides, how could you be a real artist and NOT use your art to say something subtle about your take on the political situation? So, in an odd kind of way, I owe perhaps more to my Afrikaner brethren than to my politically torpid English compatriots, who all seemed so much concerned with upping their social status and wealth that concern for others outside their social circles – that is, the common man – was seen as either a passing fancy, or some kind of neurosis. At least, the Afrikaners got me thinking about right and wrong. And, by the way, did I fail to mention that my grandmother, my father’s mother, Madeline Wessels – the one adult in all my family from whom I felt unstinting love and adoration as a child, who died far too soon – was from a prominent Afrikaner family, making me part Afrikaner, as well?

The key difference to understand about South African politics circa 1970 and South African politics after the advent of universal suffrage in 1994, is that the ideological divide back in 1970, when only whites could vote, was, for the most part, based on a voter’s preferred home language – either English or Afrikaans. Today, the lines of ideological difference depend mostly on what tribal language you speak at home. There are 9 major ones. English and Afrikaans are seen as facilitative languages that are used to provide a universal communications format for use in law, business, and education etc, but are not politically determinative, because whites are only a small part of the electorate.

The money thing remains a potent force, however, and it hasn’t taken blacks long to catch the bug. How soon we tend to forget our ideological zeal when we get rich. Far be it from me to claim that I’m somehow immune; but, you know, I wouldn’t mind testing out the principle on myself….

As a Slovenian, no doubt, you recognize something of the post-Tito Balkan situation in what is happening to South Africa today. May it not go that far.

With respect to there being an element of protest in some of the songs on the album, I hope people will recognize that only a fraction of the subject matter exhibiting some theme of disapproval has any direct connection to a known political issue of the time. Most of it is just social commentary. Take the song “One Quiet Sultry Sunday”, for instance. It may well have been the first time ever that a song of that nature was offered up in a public concert in South Africa. As to whether other songs of a similar nature had been performed in other countries, before that, I’m not sufficiently educated on the subject to be able to know. This reflects something that songwriters can do; namely, shine a light on something that the public might pay more attention to and, in some cases, refer to its political representatives for legislative action.

What can you tell me about the cover artwork for The Memoirs of Hakeford Wart (Goodbye Capetown)?

Well, for one, it’s one aspect of the album that I really like. It’s so zany that the first time I saw it again, after not seeing for the previous 38 years, my first reaction was like”Wow! That’s totally nuts! Did I really do that?” Yep, I really did. It reminded me that I smoked back then, not a whole lot, but socially.