No More Beatlemania: The Monks Meet Rock & Roll By Zack Kopp

An unconventional musical act composed of former U.S. GIs in Germany, the Monks were active for a few years in the sixties before Polydor records spoiled the party by demanding a more traditional sound.

Bassist Eddie Shaw exchanged emails with Zack Kopp recently regarding the band’s bizarro twinship with their incongruous contemporaries the Beatles.

Originally called The Torquays, which lineup included most future Monks, plus a vocalist named Zack something and a German guy named Hans on drums, the gang of mostly-expatriate friends had a fun-loving spirit amid the military starkness. “We played a club called the Maxim Bar in Gelnhausen. It was where GIs went off base to drink and find females. We called those nights the ‘Saturday Night Fights’ because before the night is over, someone would get into a fist fight over some girl and then the military police would come in and throw a tear gas grenade to clear the place out. Larry always bought his gas mask with him and put it on while the rest of us were rushing to get out the door. He would sit on stage and play ‘Green Onions’, until the MPs made him get out. That way he could claim we played the required time. Therefore, the bar owner owed us the full sum of our contract. Hans always watched us with a slight smile on his face, as if asking, ‘What are they doing? ’I think he worked for the post office.”

“Anti-Beatles”

The Monks are underrated, little-known, and hard to find the truth about, unless you consult bassist Eddie Shaw’s website or the books he’s written on this one of a kind band’s exceptional story. For a long time, they didn’t even have a Wikipedia entry, and now that they do, some of the facts are blurred or incorrect. “I have never read Wikipedia about the Monks,” says Shaw. “I don’t want to. Everyone has their own conception of who we were. Some claim we were born in a petri-dish. My favorite is the one by the girl group Pussy Galore who told People Magazine that they had heard a recording of a band from Germany named the Monks.

The Monks were GIs and were AWOL from the army. While the Military was looking for them, they showed up on TV singing, ‘I Hate You but Call Me’. And then they disappeared to never be seen again. Each one of us was influenced by his own musical heroes. Mine were people like Miles Davis or Moondog. Larry’s was the guy who played ‘Green Onions’. Gary’s influencers were north-woods folk artists. Dave’s was of course, Elvis Presley. And Roger’s was? He never talked about music. He beat the drums without using cymbals and that’s all I knew about him. He didn’t talk about himself much. As it turned out, we became the owners of our sound. It was a sound no other band had. You can identify the Monks as soon as you hear them – just like the Beatles. It’s ironic that the members of the Beatles claim they got their professional chops playing in Hamburg. The Monks did too.”

“Make them watch you as if in shock.”

The Monks are one of the more notable sixties acts, in terms of uniqueness. I found out about them when I learned what I thought was the Fall’s ‘Black Monk Theme’ was a cover as a teenager. My subsequent research was briefly complicated by the existence of an English punk band by the same name, but the first Monks don’t sound like anybody else. “Every person in the Monks came from a different musical background,” Shaw explains, “Gary Burger was a country player. Dave Day played Elvis (“My life started the day I heard Elvis”), Roger Johnston was a Texas swing drummer. Larry was a classically trained piano player (mostly played in his living room) and I was a multi-instrument jazz player. In order for us all to get along, we had to deliberately forget our influences and preferences. To play together we had to adopt to a much simpler (yet complex) form of music known as Uberbeat, which we invented. We worked to find the tension points of a song, and this sometimes required 13 or 15 bars instead of the normal 8 or 12 bar compositions. The music sounds easy to play but it is more complex than that. Our managers first heard us and picked us up in Stuttgart where we played for a couple of months. Because of boredom we had experimented with the audiences there. According to our managers, if the audience was not paying attention to the band, then it was a failure. If they loved you, it was also a failure. The best response was to have them arguing about the band on stage. “Make them watch you as if in shock.” We were getting our haircuts when Roger decided to have a tonsure. That’s when we all decided to do it. Our manager Karl said, “That’s it!’”

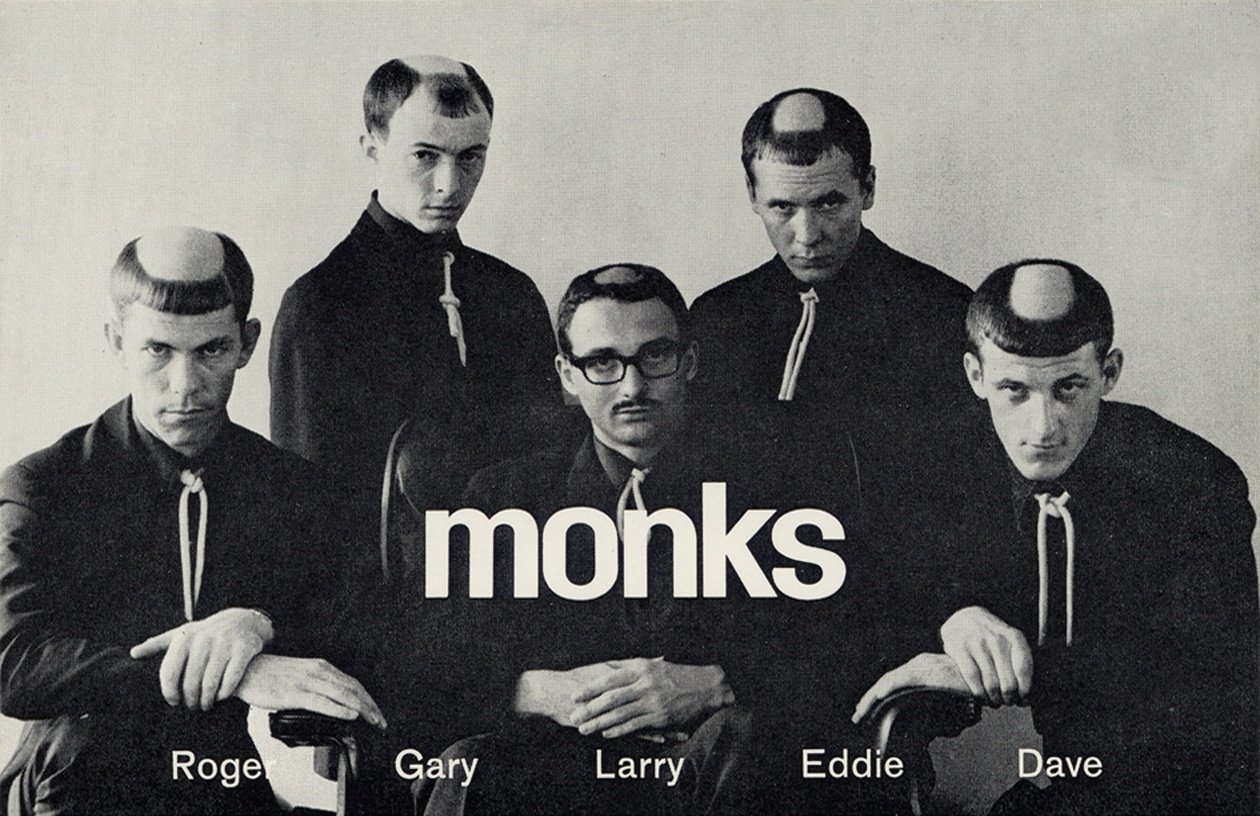

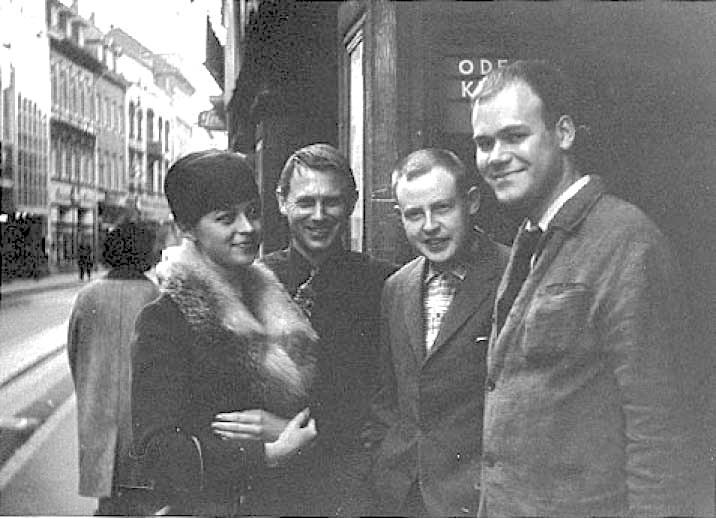

The Monks shaved their hair in Monk’s tonsures, a ring of hair around a bald crown, and wore dark cassocks onstage at the same Hamburg joints rocked by fame-bound Liverpool acts with slicked back pompadours a few years prior as they sweated through the same kinds of grueling shifts as entertainment for the various clubs in Germany. They never thought of themselves as forerunners of anything, and dressing like Monks without acting like Monks in the heavily Catholic Old World of the 1960s may not be connected to Crime playing San Quentin dressed as cops in the late seventies, but is perhaps the first emergence of the shock-rock credo. “There were many, many accusations of blasphemy from many sources. Old women loved us when they saw us on the street, but when they saw us flirting, drinking alcohol and using profanity. they were shocked. The further south in Germany (the more Catholic) we went, the more anger we would raise with some people. We were even attacked onstage during a concert in Munich.”

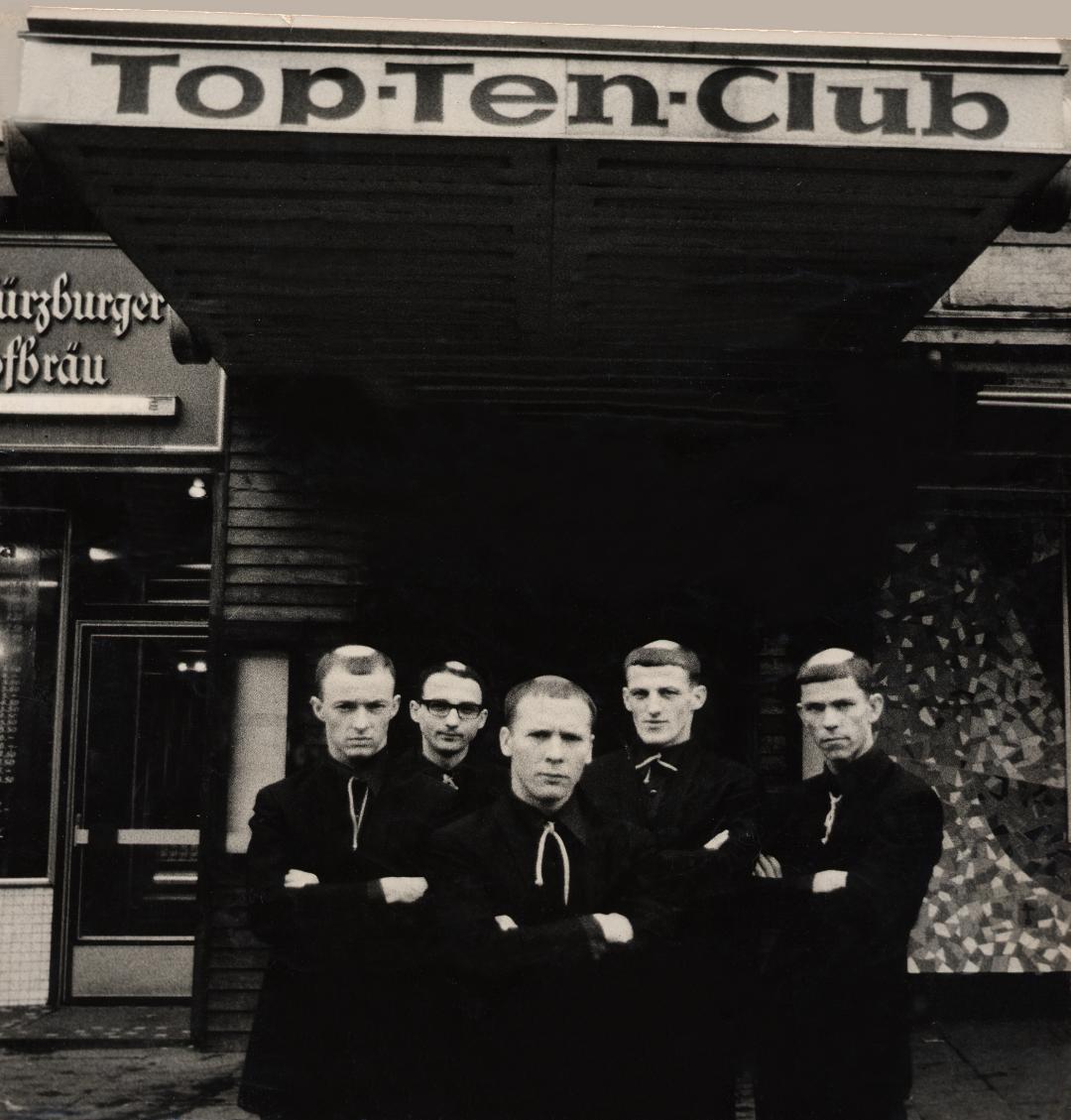

Hamburg’s Reeperbahn district, referred to as the “Grosse Freiheit” (“great freedom”) by addled patrons, where they often found themselves playing places like the Top Ten Club, has long served as a destination for English acts from the Beatles to the young Billy Childish, and acts from elsewhere in Europe, but the Monks were unlike others in this crowd as disaffected Americans kitted out with robes and weird haircuts. “One thing we noticed was the type of girls we attracted. They were not the innocent young baby face types screaming for Beatles. Our fans were young and they had experience. We liked that. We experimented and lo & behold! the Monks were born. All of a sudden – a rainbow colored life.

From there we went to Hamburg and found ourselves in the middle of many well-known Beatle-ites.

People like Tony Sheridan (‘My Bonnie Lies Over The Ocean’) hated us, but we managed to get our own fan base there and after awhile – when we sarcastically would play the Beatles tune, ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’. The audience would sing along with I want to fuck your hand. Hamburg was a place of wild rowdy people and we fit in well there. The newspapers began to call us the anti-Beatles.”

Eddie Shaw is one of two surviving members of this cluster-busting act, along with keyboardist Larry Clark, who lives in Murfreesboro TN, retired after some years as a computer technician, and who Eddie says has stopped giving interviews as far as he knows. The Monks never had a mop-top phase, but the presence of German visionaries as advisors at a crucial formative moment is another bizarro parallel between the two disparate acts. Where the Silver Beetles had Klaus Voormann and Astrid Kirchherr, the Monks had pa brace of postmodern consumerists. “Our managers were well-known in their business as advertising people,” he says. “There were four of them: Karl Remy was the “idea” man. He kept referring to us as playing the music of the future He won a prize for his TV ad of the year, featuring Volkswagen. Walther Niemann was the “managing” manager who found compromises for all the arguments we got into. Gunther and Kiki were our graphic artists and publicists. And we had one more manager, Wolfgang Gluzszewski, who managed our tours. I believe they are all deceased now. I heard Kiki committed suicide.” Monks frontman, lead guitar player and vocalist Gary Burger passed in 2014, after a brief stint as mayor of Turtle River, Minnesota—“When Gary died, it felt strange. I had no clue because the news was not shared. I got the info from a person I did not know. Turtle River, MN had a population of about 70 people, I think”—as did drummer Roger Johnston—”he was the first to pass. He was living in Bemidji, MN and played one reunion tour in NYC (1999). I think he died the next year,” and rhythm guitarist Dave Day, who Shaw says, “played all the reunion tours with us until he passed in 2006. He is buried about 50 yards away from Jimi Hendrix in Renton, WA.”

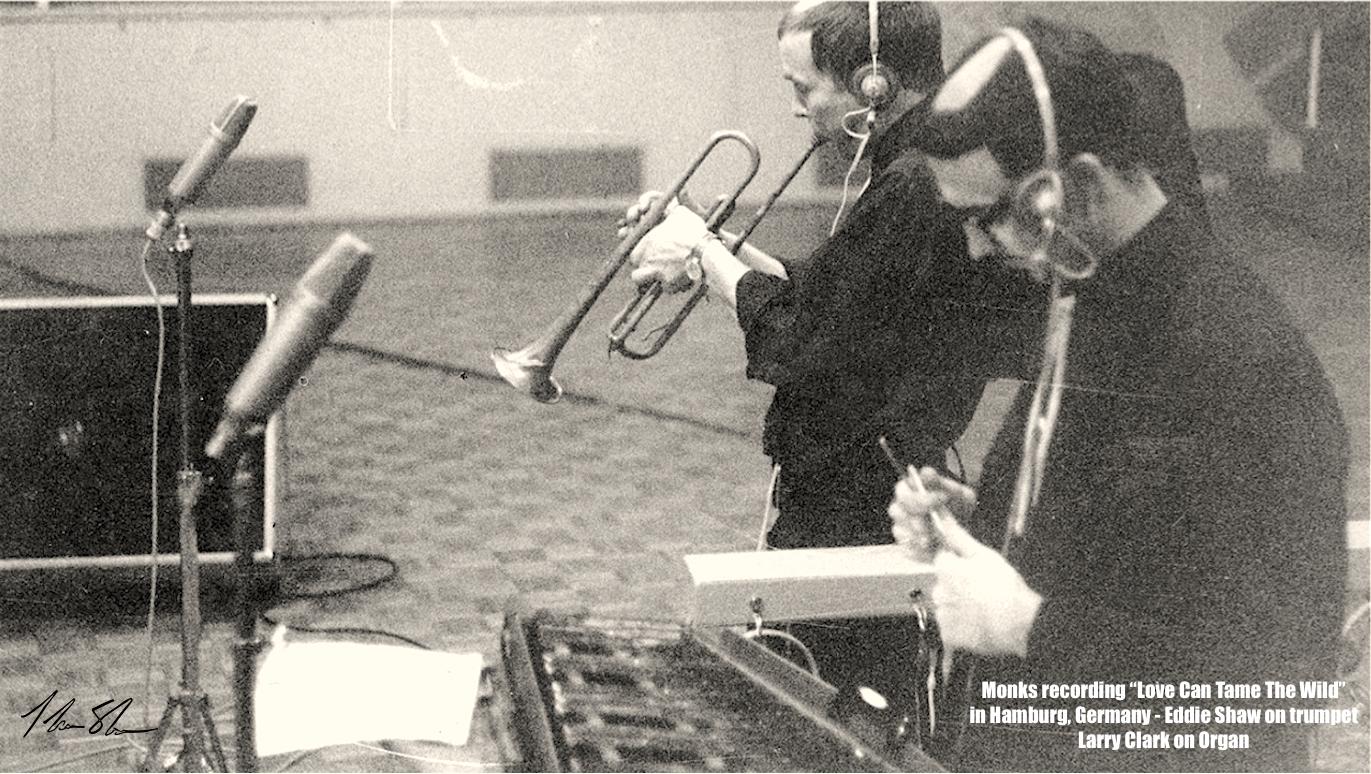

Besides having written a memoir of his time in the Monks, the authoritative text on that outfit’s formation and heyday, ‘Black Monk Time’ (1995) Shaw authored a sequel to that volume called ‘Black Monk Time Too’ a journal of the band’s late nineties reunion tours in the U.S. and Europe—”After years of not speaking about the Monks, I was awakened by two people at the front door of my house, in Carson City, asking if I was Eddie Shaw of the Monks. From that day on things changed for all of us. I was surprised to learn that many Monk songs are being covered by many groups, including movie soundtracks like Big Lebowski. Our music was earning us money, something I had never expected. That’s when we (The Monks) were asked and decided, as a group, to get together and play a number of reunion tours, starting in NYC and Las Vegas in 1999, ending in London, Berlin, and Frankfurt in 2006.” Shaw has written several more books, including a collection of short stories titled, ‘A Cowboy Like Me—Vol. 2’ “all names have been changed to protect the guilty,” and a historical volume on Giacomo Beltrami’s discovery of the source of the Mississippi River. The latest and greatest is one called ‘Passing Through Minnesoda and Other Altered States’ to be published in August 2021, which is a fictionalized memoir of Eddie Shaws’ musical experience in the 1970s. An accomplished musician, he also has some non-Monks recordings available, ‘Minnesoda/Copperhead’ 1970’s – songs recorded in three different studios – Minneapolis, Chicago, Nashville (from the memoir, ‘Passing Through Minnesoda’), and ‘Jass in Six Pieces’ – Eddie Shaw and the Hydraulic Pigeons, experimental jazz tracks with Eddie Shaw on Trumpet.

Wikipedia makes reference to the band’s innovative managers advising them to tour Vietnam and cement their anti-war reputation, but it fell through at the last minute. “The day we were supposed to leave was after a two-week vacation. When three of us showed up, in Frankfurt, to depart – it was the same day we received the message from Gary saying he went home to Minnesota . … and Roger went home to Texas. They didn’t think it was a good idea to go to Vietnam, especially after one member of Tony Sheridan’s group was killed by a Viet Cong terrorist who threw a grenade of the stage as they were playing in Saigon. When I read Gary’s message, I gave a sigh of relief. I was tired – as we all were. After working six months in Germany to get money to buy my way home, I and Larry caught a tramp steamer. On the boat I read a newspaper article stating the Monks had broken up and Larry was suing Gary and Roger for breach of contract. When I asked Larry about it, he denied it.”

When asked who, if any of the bands contemporaries had an influence on their sound, and how he would describe the Monks influence or effect on the musical scene to follow, Shaw says, “The Fall was one of the first groups to play some of our songs. Mark E Smith was a good friend and sang with us in a reunion concert in Berlin. He also almost knocked the onstage photographer off the stage when the song was finished, and he was walking off stage. He liked to shock the audience. It was great fun. People liked us and they even knew the words to the songs. That’s in ‘Black Monk Time Too – The Resurrection of The Monks’.” (A word to the buyer: Shaw’s books are available far more affordably via carsonstreetpublishing.com than Amazon.com but are available at both outlets). “Monks tunes don’t compete with the human messages of, “You’re nothing but a hound dog”, or “I want to hold your hand.” But consider this; as it is with humans, there may be only six degrees, or less, of separation in the musical outcome. If the vibrations of thousands of compositions can be reduced to just one of six total existing songs worldwide, then how it is played creates the unique DNA of its existence. This DNA explains how The Monks are identified. Recently, I heard of a new group calling themselves the Monks. After a friend introduced me to them, I asked one of them, ‘Why are you using the Monks name? Wouldn’t you be more successful if you called yourselves the Beatles.’ He had no response. I thought it was funny. Okay, you got it, Zack. That’s my piece of information.”

Zack Kopp