Russ Heath: Interview with a Legend | By Sean Mageean

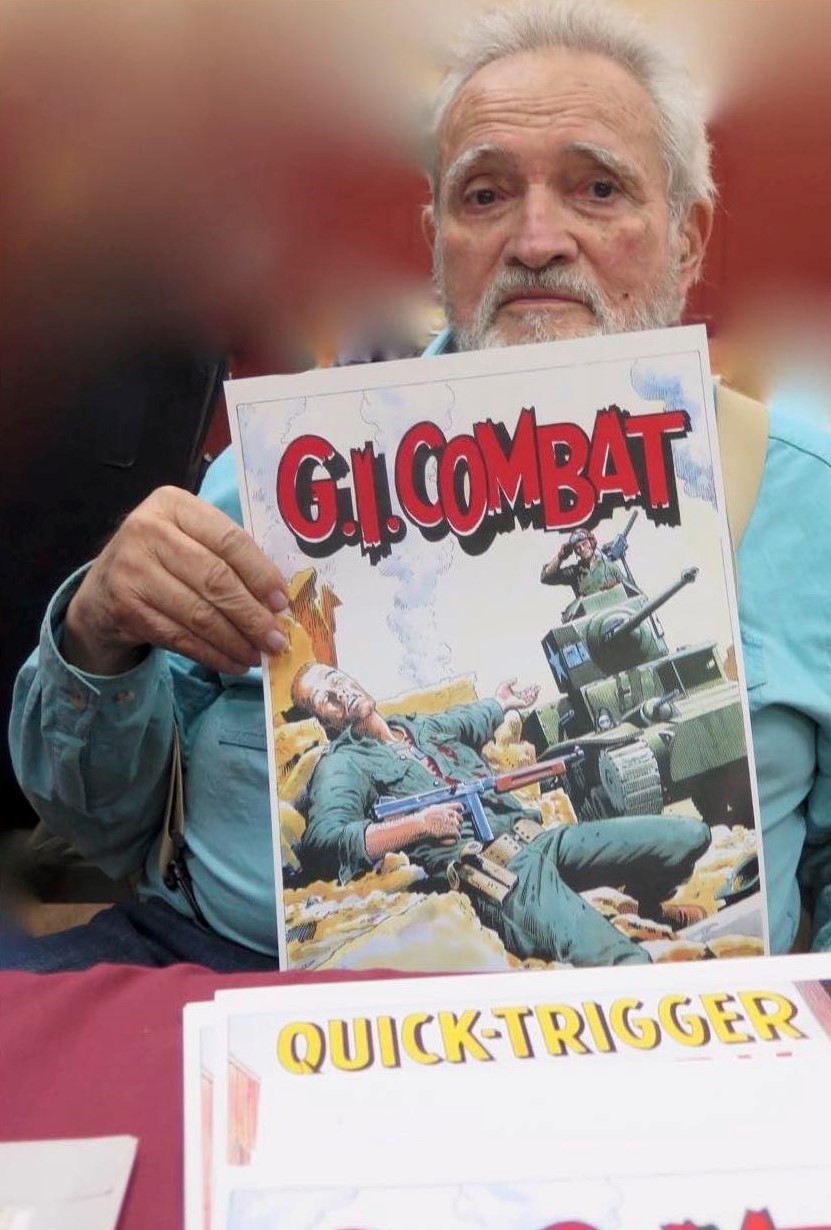

Before he passed away on August 23, 2018, I interviewed legendary comics illustrator Russ Heath during the spring of 2017 at the San Fernando Valley Comic Con in Granada Hills, CA.

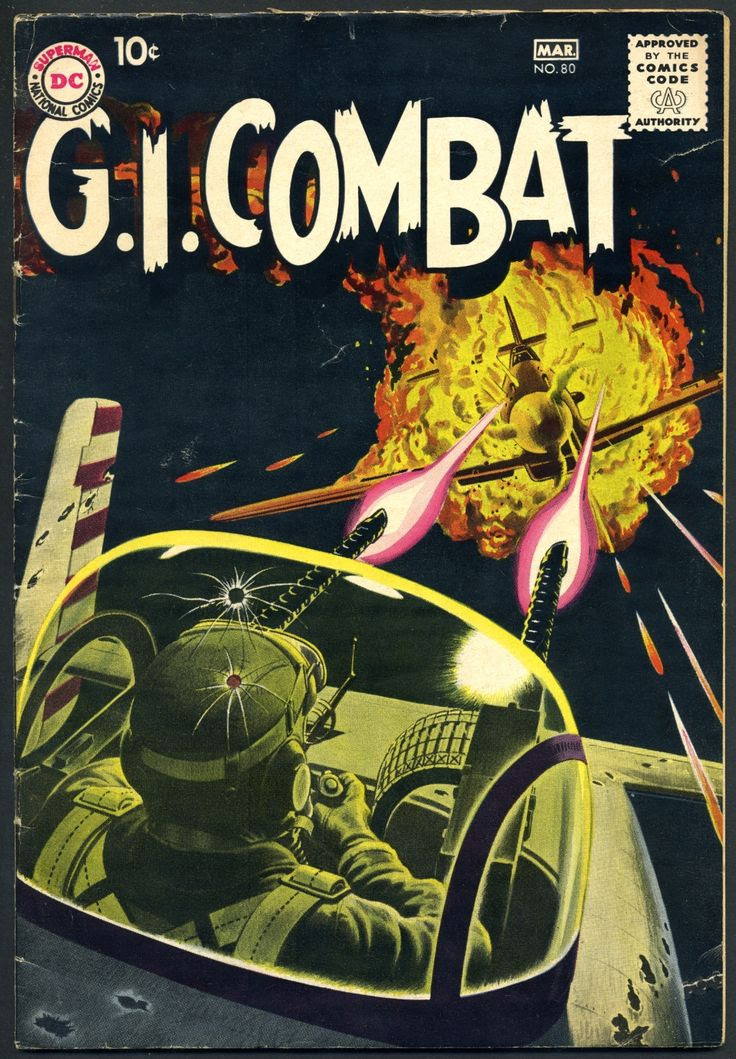

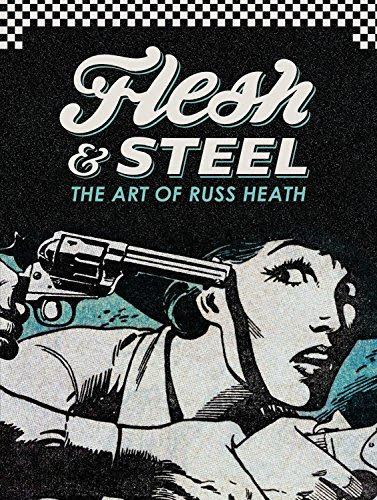

From his start in the industry at the end of the Golden Age, working on such characters as the Two-Gun Kid and Kid Colt for Timely/Atlas/Marvel, to his brief stint at EC Comics working on ‘Mad’ and ‘Frontline Combat’, to his impressive Silver Age work on ‘The Sea Devils’, ‘G.I. Combat’ and other DC Comics war titles, to his work as an assistant on Kurtzman and Elder’s satirical ‘Little Annie Fanny’ featurettes for ‘Playboy’ during the ’60s, to his beautifully rendered horror stories for Warren magazines, to his work in the animation industry, to his various Bronze Age through Modern Age work at Marvel, DC and other companies, Heath was one of the top illustrators in the business. His attention to detail, fine craftsmanship, beautifully rendered women and superior draftsmanship made him one of the top tier comics artists for over seventy years. Ironically, Heath was perhaps most famous for his two pieces of commercial art–one depicting Roman soldiers, the other depicting Revolutionary War soldiers–which ran as advertisements for bas relief plastic soldier sets in countless comics throughout the ’60s and ’70s. Heath won the Inkpot Award, Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame Award, Comic Art Professional Society Sergio Award, and the National Cartoonists Society’s Milton Caniff Award. At ninety years of age in 2017, Russ was still going strong, and as I was about to commence with the interview, an attractive woman came up with a bottle of wine for Russ– which she said Larry Hama had said to give to him. She also had a copy of the IDW compendium on Heath’s career, ‘Flesh & Steel’, for the artist to sign. Her presence–like that of a benevolent muse– lead to a lively interview, and Russ Heath definitely had a great sense of humor and a lust for life.

During your career in the comics industry did you prefer working in one genre over another? War comics, westerns, horror, et cetera?

Russ Heath: Well it changes as you grow older–now I only draw nude women (laughs).

How did you first meet Harvey Kurtzman and end up working with him at EC Comics and later assisting on Kurtzman and Will Elder’s satirical ‘Little Annie Fanny’ comic in ‘Playboy’?

He was on his way up to see Stan Lee during his ‘Hey Look!’ days [Kurtzman worked on one page gag strips called ‘Hey Look!’ for Timely comics–which eventually became Marvel comics– from 1946 to 1949], and he was up there one day and I met him and we went to lunch, and that was the beginning of our friendship.

You worked for Kurtzman at EC Comics on ‘Frontline Combat’ and ‘Mad’ when it was still a comic. Can you talk about that?

I did a thing called ‘Plastic Sam’ [for ‘Mad’ no. 14 (August, 1954)].

Right. A great parody of Plastic Man that Kurtzman wrote and you drew. What about the war story?

Then there was a World War I story. “O.P.”–which is Observation Post [for ‘Frontline Combat’ no. 1 (July/August, 1951) In the story, a soldier is stationed at an Observation Post in the trenches. He is connected to his commanders by phone line. He ends up calling in an attack on his own position, after the Germans have captured his trench–and he is blown up along with them.]. Years later I discovered that EC was giving vacations all over the world to their workers. I should have gotten in more closer and I’d have gone. I didn’t know that was happening. Although they weren’t allowed to take their wives or girlfriends–so that might have put a sour note in it.

How did you first meet Joe Kubert and get involved with doing all the DC war comics–‘G. I. Combat’, ‘Our Army At War’, et cetera?

Well, in those days when the season was over, people were let go, and they’d make the rounds of all the places an end up scattered in a different pattern. And three years later they might be repeating themselves again. So everybody goes out and looks for work. I went up where Joe Kubert was doing the first 3D book.

Oh, ‘Tor’, maybe? The prehistoric caveman character Kubert created. ‘Tor’ in 3D?

I worked on the first issue. I did two dinosaur pages by myself, which are in the book. [The second issue of ‘Tor’, which Kubert produced for St. John Publications in 1953, was re-named 3-D Comics, before returning to being named ‘Tor’ with issue 3.] So that’s how I met Joe Kubert.

Okay. I read that you actually would buy uniforms, collect helmets and make models so that your war comics were as authentically rendered as possible. Could you comment on that?

Most magazines or books you could buy on airplanes had parked airplanes and you don’t know what it looks like on the bottom or at a weird angle. So, I started buying the models and making them so that I developed a way of drawing them. There was one that I did for three or four panels looking up…this bomber… that was a B-17 [Flying Fortress] that I did. That was a great aircraft. Of course, I used them more than once. Speaking of Joe Kubert, we were both at one of these cons, giving a conference. He takes the first half hour, I take the second half hour. As the subject he chose to talk about was research, Joe told all the kids that you gotta have tear sheets. You see a picture of a tank, tear it out and put it in your file because you may have to draw it. So you need to build a file over the years. So, he’s telling me–well he’s telling everybody–how important it is to be accurate. And he used as an example one of the war stories that one of the guys from DC, Mort Drucker, had done. And it had voice overs from the nosewheel of the bomber. It showed the bombs leaving and the bombs coming down, you know? And he finished and he says: “Now it’s your turn, Russ,” and I says: “But Joe, B-17s didn’t have a nosewheel” And everybody cracks up…he cracked up, too. Then he says: “What?!? You just ruined my half hour.” (laughs)

What are your remembrances of Robert Kanigher? Did you enjoy illustrating his scripts on The Sea Devils and The Haunted Tank stories in ‘G.I. Combat’ for the most part?

He thought he was so great because we were going out to lunch, the bunch of us, and he’s not. And he says: “I’ll write you a script.” After lunch I go back to get the script–that shows you how much he put into it. And he’d use a lot of the same stuff over and over–like a grenade down the muzzle of a tank. Well, in reality, with all the steel that’s in a tank’s muzzle, it wouldn’t touch it. And he had that as a filler in some of his stories. And he had this thing where there’s haystacks and there’s ack-ack guns hidden and the Stukas are coming down…who wants to see the same thing again and again in another story? I wanted space to make drawings. I figure people like to look at something…so I would just cross off a page or two. (laughs). Expand the rest of it into it, so there’s still the same number of pages. I thought I’d catch hell. But he either never looked or never noticed.

That’s interesting–it sounds like you made it almost Marvel method?

No, I was much happier with a full script. The first one I did [Marvel method style] was ‘Son of Satan’ [no. 8, February, 1977 ] which didn’t have a script. They said: “Do yo wanna do it?” I says: “I’ll do it on one condition–you let me color it.” They says: “No problem.” So, I finish the job and ten days later I call up and I says: “Isn’t it time for me to start the coloring? ” And she says: “Oh, we thought you were busy, so we had it done.” It’s just such a dumb business ’cause it got a lousy start. The way comics started was terrible…so, eventually they started using stuff from the Sunday funnies which was syndicated. Then they thought, why should we pay for it when we can hire guys to do it? And that’s why it was so crude. I bought the number 11 issue of ‘Famous Funnies’ when I was seven years old. With a business put together like that, it’s bound to be full of crap. I used to go crazy when some guys at DC–some of the editors–would take a job home over the weekend and have their kids color it. I mean, that’s not an artist. They don’t know anything about lighting.

Building on the origins of the comics industry in the 1930s and the Sunday funnies connection, when you were a kid did you like Milton Caniff or Alex Raymond or Hal Foster? Who were your influences?

Somebody got me an audition for Caniff–it didn’t pan out. I wasn’t that interested…he wasn’t that different from the rest of them in the beginning. I did get some signed originals which I had on my wall for years. But I didn’t go to work for him. And I’m just as happy, because I noticed the people who go to work for somebody else–eventually their work looks like the other person’s. I worked for George Wunder, who took over after Milton Caniff stopped the strip [‘Terry and the Pirates’].

Oh, you were an assistant to George Wunder on ‘Terry and the Pirates’?

Yeah, But that didn’t last long. And I’m glad, because I noticed that George Evans took the job later and his stuff started to look like George Wunder’s–and I hated his work! (laughs). [Wunder] felt you had to fill up any space. No white space. But white space is very valuable–it makes what isn’t in the white space important! It drove me nuts. But at 5 O’ Clock, I’d quit and make George Wunder and his wife and myself cocktails. Then, we’d go back to work after the cocktails and work until four in the morning, eat a loaf of bread and finish off a bottle of scotch.

I read that you were a fan of Charlie Russel–the old American West artist. Can you elaborate?

He was one of my idols as a kid. Of course, my father had been a cowboy. That made me, when I was at school, a big shot.

You joined the Air Force in 1945–is that right?

Yes, I signed up ahead of time. I was also a member of the Civil Air Patrol. Flying around in a Piper Cub, and I’d take the stick and go like that and, zoom, you’d go up there. Then later I flew in a B-24 Liberator, and the pilot says: “Here, you wanna take the stick?” So I took it. And he says: “Now make a 380 degree turn.” And you pull the wheel over and 1, 2, 3, 4, 5–now the wings start to come up, and it’s an entirely different ball of wax. I almost fell out the window. And my hat flew off. (laughs). I made a grab for it and almost went with it. And I had to walk almost two miles to get my hat ’cause I was out of uniform without a hat!

Did you do any art during this time for an Army newspaper?

Yes, I did. My papers didn’t arrive when I got transferred, so they put me on K.P.–and I didn’t like that. I almost got scalded by bacon grease. So I went over to where the camp newspaper was published and they put me to work–taking advantage of my being an artist. They had me painting: “Squadron R” on garbage cans–with a stencil. (laughs.) Yeah, a lot of original work with a stencil!

So, jumping around a bit, apparently you inked a story–“Hammerhead Hawley”–for ‘Captain Aero Comics’ in 1944, released by Holyoke Publishing. After the war, in 1946, when you first did work for Timely/Atlas/Marvel, what was your first assignment? Kid Colt? Two-Gun Kid?

The first thing I did for Timely–which by then wasn’t called Timely, but, anyway–was, despite some accounts that are wrong, I did Two-Gun Kid. And Stan says to me: “You don’t have to commute everyday, just bring it in once a week.” So that saved me some train fare. And then eventually I did Kid Colt and a bunch of their western characters–not all of them, but a bunch. [Heath also drew the Human Torch, Marvel Boy and various war, horror, science fiction, crime drama and satiric humor stories for Timely/Atlas throughout the 1950s.]

Jumping around a bit more, I read a story that when you were assisting Kurtzman and Elder on ‘Little Annie Fanny’ for ‘Playboy’ in the 1960’s, you took up residence in the Playboy Mansion in Chicago. What was that like?

(laughs). Well, there were a bunch of us. Harvey and Willy. Harvey tried to use all of his friends that were artists [including Heath, Frank Frazetta, Jack Davis, Arnold Roth and Al Jaffee] at one time or another. But when you have an artist that is a cartoonist–and especially the better ones–they are so much them…like, what’s the one that had all the ‘Time’ covers? Jack Davis. The minute you take their difference away, they’re a common, everyday worker. And you just don’t have any flavor left. So, part of my job was– as well as doing my own flavor–was to take ones that they’d messed up and to bring them back to look like [Little] Annie Fanny. So [Hugh] Hefner had to look at everything…the sketching and the drawing…so at first we were out running back and forth from New York to the mansion. But those guys had wives at the time and didn’t want to be away from home. So they said: “Let’s just leave Russ there and he can wait ’til Hefner can see him. That could take a week, two weeks, three weeks…and I was asking Harvey for a raise…I had four kids to feed. And nothing ever happened. So finally I got fed up and I said: “Harvey, I quit. Come down and take all this crap out of here.” And he panicked…he used to say: “Well, you’re working for ‘Playboy’, my God!” as though that would make up for the lack of money! It’s like what they’d do to my father…they’d give him new drapes or a new carpet in his office…but you can’t eat off of that. So, anyway, by 5 O’ Clock that day, Hefner’s on the phone, and New York in those days was terrible–you couldn’t carry enough ammo to go on the subway. And he knew I liked Chicago. In New York, if you looked at a pretty girl, she’d look at you like: “If you speak to me, I’ll punch you right in the face.!” And in Chicago the girls would go: “Hi!” Huh? What is this? So I liked Chicago by comparison. So Hefner says: “I’ll tell you what I’ll do. I’ll double your salary, I’ll move you lock, stock and barrel from New York to Chicago, and I’ll give you my old office to work out of.” A deal I couldn’t say no to. Eventually I was in his mansion so much that they got me a suite…they stashed me in the suite and brought me up a drawing board and got me settled in there with music from Hefner’s private collection to listen to…and then all the girls that were walking through the hall would come on in and see what I was drawing. I remember one of them; we talked for half an hour. I said: “I think I’ll take a break and sit on the couch and talk to you like a normal person”. Then I realized I couldn’t even offer her a drink because there wasn’t anything in the suite. So I called down and said: “Can I get some red label up here?” They said: “Right away, sir.” (laughs) I expected to get a bottle and a couple of glasses–and they bring a wooden case with 24 bottles of red label. Now, she didn’t get out of that room until the next day…(laughs). We dated for a couple of months.

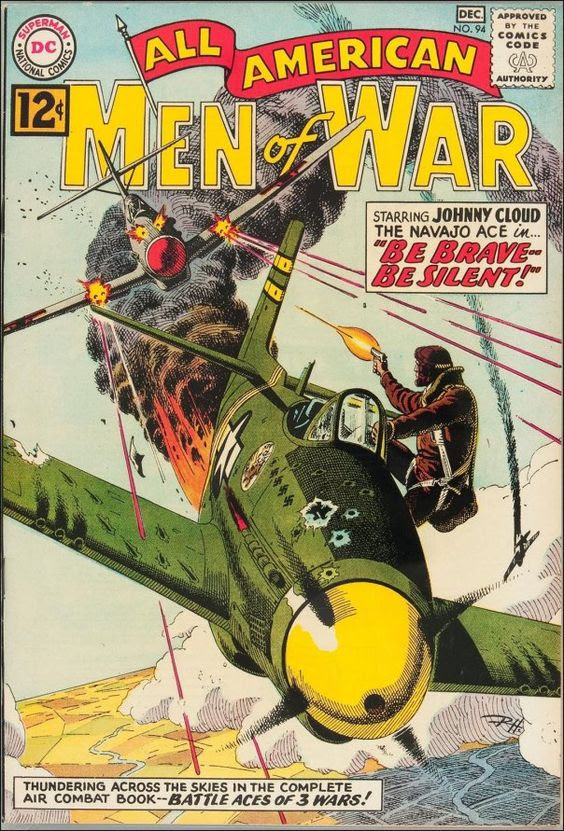

How did you feel when the Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein appropriated some of your war comics panels from ‘All-American Men of War’ no. 89 for his paintings ‘Blam’ and ‘Brattata’?

Well, I got a call from MOMA–the Museum of Modern Art–and they said: “We’re having an exhibit, and we have your comic page and the painting [based on Heath’s and Irv Novick’s DC war comics art]. Then [Lichtenstein] sold the painting–I think–for $44,000,000. I couldn’t go ’cause I had a deadline. But the sonuvabitch never even bought me a cocktail! (laughs) But a few month ago, somebody calls me and says: “You know that thing that [Lichtenstein] stole from you? I want you to steal it back. I want you to do one of his paintings.” Then, he says: “How much would you want to do a painting like that?” I said: ” $500 to start, and $500 when I’m done.” So he says: “Okay.” So I hung up, and I thought, I’m gonna call Neal Adams and tell him about that. So I did. And Neal says: “Are you out of you mind?!? Do you mind if I call this guy? I’ll call you back in a few minutes.” So he calls me back in an hour and he says: ‘Now here’s how it’s gonna be. He’s gonna send you a packet on how he wants you to do it. Forget that. I’m sending you a packet and that’s the way you’ll do it.” I said: “Do I still get my thousand dollars?” [Neal] says: “No. You get ten thousand dollars!” (laughs) Finally, I got a little bit back!

That’s great! Neal Adams has always stood up for the writers and artists in the industry. What about Wally Wood–were you two friends at all? You both have superior draftsmanship and a predilection for hot women in your work. Any anecdotes or memories related to Woody?

I have very few, because we didn’t cross each other’s paths. I did see him a few months before he killed himself–and he was in bad shape…he was supposed to go on dialysis but he told me he wasn’t going…that’s my last memory of him. He was very good–one of the top guys.

What are your memories of Rocketeer creator Dave Stevens? You both worked together doing animation, right?

I left ‘Playboy’ because no one seemed to be able to tell who did what, and they couldn’t get it straight. So, I thought, I’m part of a team, it’s my history. And I thought I’d rather do it by myself or get some other kind of work. So I quit. We started ‘[Little] Annie Fanny’ in about ’61 or ’62 and I quit in ’69. I didn’t make out too well. Then Carmine Infantino– then the editor of DC–wanted me to come back to New York…’cause in those days you had to be in New York to work for the comics. And I said: “I can’t make the trip.” And [Infantino] says: “We’ll advance you a couple of grand to make it back, which we’ll get back from jobs that we’ll give you.” So, that’s how I got back. But I couldn’t handle New York–it was depressing. So I went west to Connecticut and worked from there. Eventually, that wasn’t working either and, uh, it’s funny, there’s a side story; the lady I was going west for in Connecticut, eventually I left [her] when I went to California [in 1978]. And I called her up: “How are you doing?” And she said: “Oh, I was so sick.” And I said: “Why didn’t you go to the doctor?” And she said: “I never had a doctor.” She had spent her life there, but hadn’t got a doctor. So I said: “Take the number of my old doctor there.” I gave her the number of the doctor–so she married him! (laughs) Then I went to work for Hanna-Barbera and [Dave Stevens] and I shared a cubicle. We weren’t close in age, but we both liked a lot of the same things.

Did you and Stevens both have an appreciation for Bettie Page?

Yes! (laughs) One day we were walking down the hall [at Hanna-Barbera] and he didn’t care about lunch and neither did I. And he says: “If we could get on that roof we could get some rays of sun.” So, I says: “If we go up that ladder and push the cover, we’re on the roof.” So, up we go. And we stripped down to get tan and were only in our briefs, and I says: “If anyone catches us up here–we’re dead!” (laughs).

You did animation projects for Sunbow on G.I Joe, Transformers and Inhumanoids, right?

I ended up working for almost all of the animation houses there, including Ralph Bakshi. I worked on ‘American Pop’. [Bakshi] was a character. I was in this little office with, like, three other guys, working and he walks in and says: “Boys, aren’t I just the smartest–I hired Russ Heath!” (laughs)

Let’s talk a bit about your work on The Lone Ranger syndicated comic strip that began in 1981.

First of all, they asked one of the other cartoonists if he wanted to do it, and he said: “Will I get to keep the originals?” and they said: “No, you won’t.” So, he says: “I’ll take a pass on it, then. I don’t want it” So, they came to me. And I thought, well if they have to have the originals, I’m just looking to make some money on it. And I thought, if we could get enough papers so I could make $1500 a week on it, that would be worthwhile. So, that’s the basis I jumped in on it–and that was it. I tried to make it different. To do away with the desert and the tired conceits. What about the James Brothers? Let’s let the public see what The Lone Ranger’s winter clothes look like! And I brought in everything. He went down to New Orleans. We had Mississippi river boats; we had stampedes; we had white buffalo; we had Indians; we had everything. The agents pushing the strip only got the small papers, so we only got a small circulation. It never added up to enough money, so, after a few years, both the publisher wanted out and I wanted out.

What are your memories of working for Warren Publishing during the ’60’s-’70’s on stories in ‘Eerie’, ‘Creepy’ and ‘Vampirella’?

I loved it because it [his artwork] wouldn’t be spoiled by a colorist. And I had no limit on how well I could model or paint–even if I was painting skin grey, rather than color it. So, I knew my work would go [to the printers] as I sent it in.

How did you find inking over other pencilers to be? I know you inked over Michael Golden for a few issues of DC’s Mister Miracle (no. 24-25) in the late ’70s, for example.

Well, it was never my thing to do that. Maybe as a special favor I did it. It didn’t do anything for me. I remember Michael Golden–he’s a nice guy. He said to me that he’d learned things from me in our doing it together. But I always tried to steer away from it. There was another [inking] job with Gil Kane called “Wells Fargo” [‘Tales of Wells Fargo’, based on the TV series, in the early 1960’s for Dell comics].

You inked over Gil Kane?

Yes. But I had to re-do his horses’ legs…they were too fairy-like. (laughs) I thought, I want him to be rough and tough and have dirt on his hooves. He was too sweet.

Did you ink any of Gil Kane’s famous up-the-nose-shots? Also, he was another great draftsman–especially for human anatomy…maybe not for animals, but his classic Green Lantern work comes to mind.

Gil liked to talk more than draw. He could talk your ass off! (laughs)

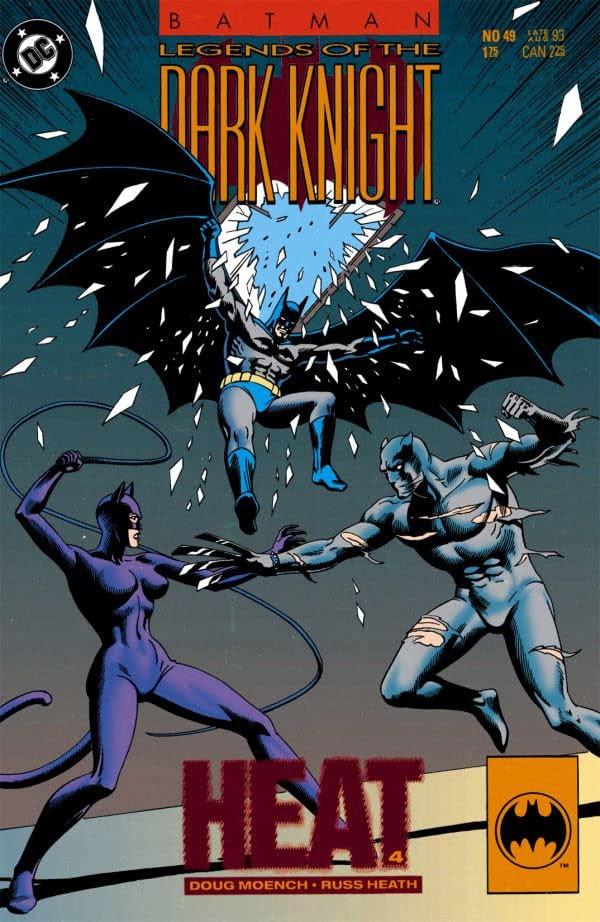

What about the four issues of the ‘Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight’ (no. 46-49, 1993) comics you illustrated? Generally, you don’t come across as someone who enjoys drawing superheroes–although those issues were really beautifully rendered.

Well, in the war comics, and all of these things, there are no straight lines. [There’s] rubble–you can’t draw rubble wrong, right? You can’t say that rock’s too big. You know, I drew a rock, for Christ’s sake! And the same thing…underwater, [as in The Sea Devils comic] everything more than fifty feet away is blurred…and nothing is ruled, so you don’t have to rule lines. The worst of all is, like, Batman when you’ve got buildings and windows…also, I’ve been against superheroes since the beginning. You know, I can’t buy Superman. He jumps over the Empire State Building. When he lands, one of two thing have to happen–he either breaks the pavement or he’ll ruin his costume! I always hope for the real. Then, one day, Superman starts to fly–no visible means of propulsion. Instead of jumping, he just started flying. And I thought, how the hell…? It’s a bad story line to begin with. Who are you going to have fight the world’s most wonderful thing? So you’ve got to invent super villains. And I thought yeah, we’ll put all the super villains on the left side of the page, and all of the super heroes on the other side of the page, and the public will stand there and watch them fight. I mean, jeez…

Which is basically what the mainstream comics industry is all about…

(laughs)

So, given all this, you probably enjoyed drawing Catwoman more than Batman for those four issues?

(laughs) [It’s] kinda [like] drawing a nude and coloring it purple.

Would you consider drawing anything again for comics or are you officially retired?

The [new] books that I’ve seen are totally unacceptable to me. It used to be, there was Joe Kubert or there was me, or, you know, a man [one artist]–not men. Now you read who did a book, they got eight people! You can’t do good stuff by committee because the back half of the committee doesn’t know what the front half had in mind. And if the colorist isn’t an artist, he doesn’t know anything about lighting–and I use lighting a great deal in my work. And, oh, it’s always continued…you have to wait to find out what happened–that’s a dumb thing to do!

If there was a publisher that was willing to use your work and you could have complete control, would you still be willing to produce work?

I’d rather do that than any other kind.

Thank you for your time. It’s been an honor speaking with you.

Book down here if there’s anything you left out and I’ll answer it.

Sean Mageean

All photo materials are copyrighted by their respective copyright owners, and are subject to use for INFORMATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY!