Thomas Olbrechts

‘Westrand’ is a solo alto saxophone album made by Thomas Olbrechts, recorded at the brutalist architecture building Westrand in Dilbeek, Belgium.

“A dialogue between Brutalist architecture, alto saxophone and recording”

Why did you choose this place? Was this your idea or the idea of Christophe Albertijn, because Westrand is not a recording studio.

The place – Westrand, Dilbeek – has been chosen by Christophe Albertijn, producer of the work and founder of the new label HUIS. One month before the session Christophe told me he was planning a new series in which he would invite musicians to make solo-recordings. For each musician he would choose a different architectural context in which the musician, in his opinion, might fit. I told him I really liked the concept, thought he would call me in a few months or a year. Already a week after he sent me an email with a link to the Westrand building with the question: ‘What would you think about this?’. I said I would give it a try, so we decided to visit the building to explore the possibilities.

Westrand, of course, isn’t a recording studio, it’s an interesting example of brutalist architecture, completely structured out of concrete geometric shapes.

When I have to play a concert or record in a studio, a gallery, concert room or whatever space I don’t know yet, the first thing I do when I enter the space is whistle. It’s a kind of reflex that immediately tells me how tough the job is going to be; in the Westrand building I immediately knew it was going to work! The acoustics of the place are quite unique, the building has a soul! Christophe really made a good choice!

How do you see the relationship between the saxophone and the space where the instrument is recorded?

Both, the saxophone and the Westrand building are conceived out of cold inert materials: the saxophone out of metal – the Westrand building completely out of concrete.

The first impression you get when you enter the building is an almost serene distant coldness, a sense of tough solidity; when you make a sound you hear a cool echo which reminds of a church but sounds much more worldly. On the other hand the atmosphere in the Westrand building isn’t cold, there’s a certain warmth in it as well.

The saxophone isn’t a wooden flute, a clarinet, hobo or fagot – it’s an industrial version of these instruments. It sounds much sharper but can also reach a warmth that didn’t exist before. The Westrand building hasn’t got the warmth of a -let’s say- a wooden temple, it sounds more like a cave, but the acoustics of the spaces as I just said also reflect a hybrid warmness. If you blow the instrument in the ‘right’ way -and this was of course the exercise of the journey- you discover a kind of concrete double bass sound box.

Perhaps the saxophone and the building have this same stoic distance in common. At first sight they give the impression of being cold but a few moments after, when the instrument starts to breath or when you enter the space the soul of both comes to life.

The rough brutalistic character of the building makes a direct appeal: it wakes you up, demands a certain lucidity; it doesn’t make you nervous but makes you aware of yourself walking through the different spaces. Maybe the sound of the saxophone, yet how I hear the instrument, appeals to this same kind of involvement.

Then, in my opinion, there’s a clear sense of direction through the building which is inherent to the sound of the saxophone too. Even if you get lost there’s always a sense of restraint, you will find your way. Also in both -the building and the saxophone- there’s this sense of frontality, in Westrand the track is always right in front of you, which is inherent to the saxophone too; the appeal to always reconsider the track you’re on. The structure of the building is very clear as well, you can easily get lost in it but that’s OK, it doesn’t feel disturbing. I always tried to reach a clear appealing tone, not a brute tone, more a tone that appeals inevitably to the senses.

Anyway, I hope the best way to get the right answer to your question is to listen to the recording!

Christophe calls you an ‘instant composer’. Does this mean that you recorded this album without any preparation? Don’t you know what you are going to play before Christophe presses on “record”? Is all the music on this album improvised?

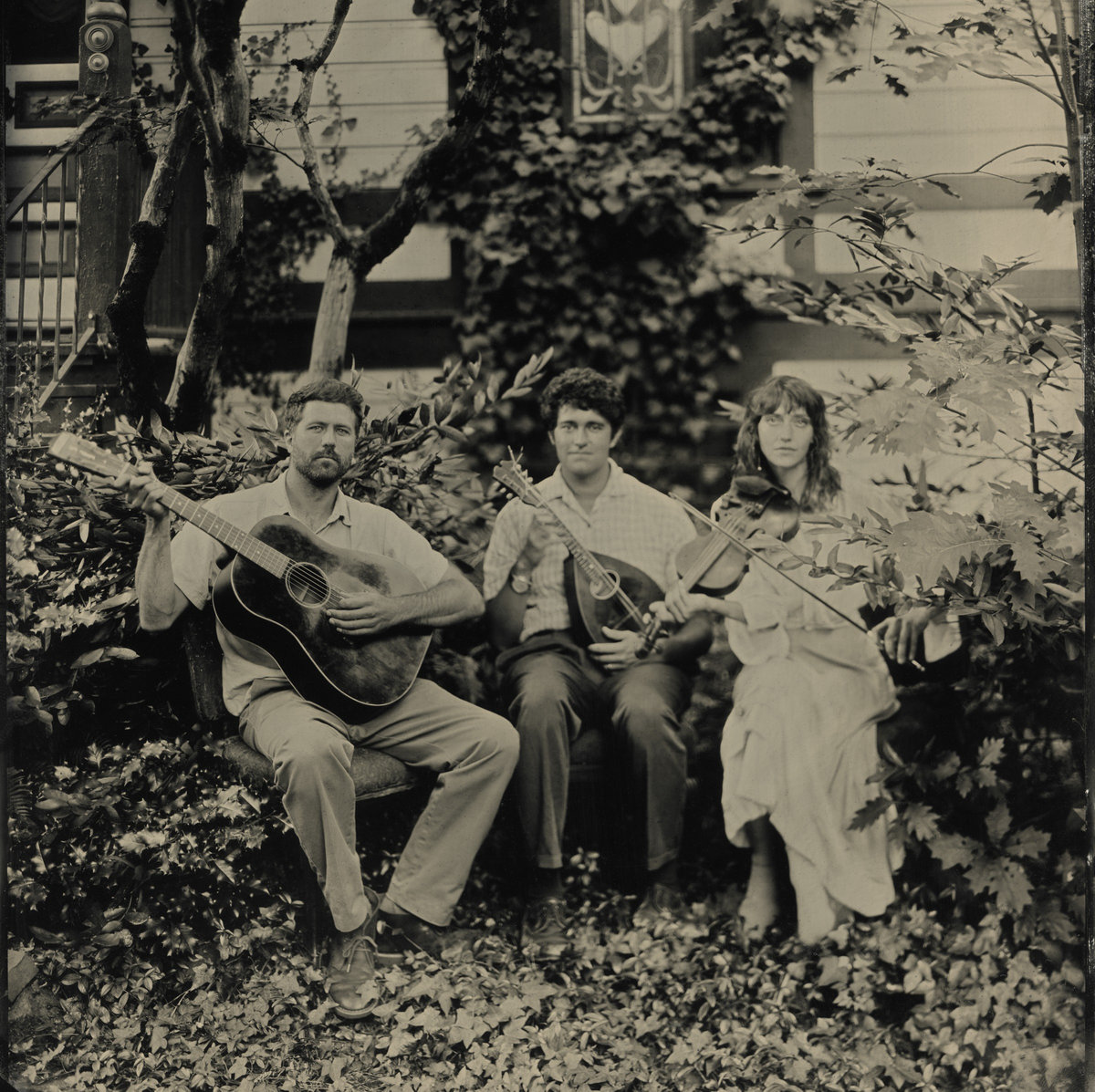

As I was saying, we visited the space one week before the recording: we walked through the building, started at the entrée, sat down for a minute on the concrete benches nicely integrated in the building – covered with colored pillows, reflecting the colors of a painting by Alfons Hoppenbrouwers himself that is hanging on the left side of the entrance hall, when you enter the building.

Then we walked intuitively to the concrete playground, ingeniously integrated into the building, we took the stairs, visited the concert hall which is very sophisticated too; every part of it is fully integrated in the whole. We finished our walk backside-outside of the building on one of the terraces, situated just above the art atelier which is also a wonderful room, a bit isolated from the rest of the building.

In a very direct way we were already more or less composing the music, considering the possibilities – different phases of the recording, walking through the building and discovering its unique identity. We decided where we would start the recordings and how we would move through the building, even where we would finish the recordings. The different viewpoints of the composition, the tracks though the building were already made. That’s composing, I guess… Then, when I start to work on something, when I practice at home, planning rehearsals or preparing a concert or recording there’s always this extremely important period of ‘preparation’. Before visiting the building I had already been studying the work of Alfons Hoppenbrouwers, and had been thinking about the concept of the project, during this period I tried to play and think as much as possible… You could call this the conceptual phase, …

Then comes the action itself, the playing which is of course linked to everything you worked on and studied in advance. At this point everything comes together. The conceptual input as well as the techniques you tried out during the preparation, the music you listened to etc.

So, yes everything is ‘improvised’, I really don’t know in advance what exactly I will play, but it’s not absolutely unforeseen, on the contrary: for the Westrand recordings the track through the building had already been more or less conceived in advance – and of course I had been working on concrete techniques and notions to deal with the sonic identity of the building.

When I’m preparing for something I try to listen to music that in one way or another can be linked to the actual context. In this case I tried to get a connection with the music that was being made at the time of the construction of the building: Coltrane had just died, Luigi Nono was creating highly socially committed music. Anthony Braxton, Steve Lacy and Evan Parker were inventing new methods to play the saxophone.

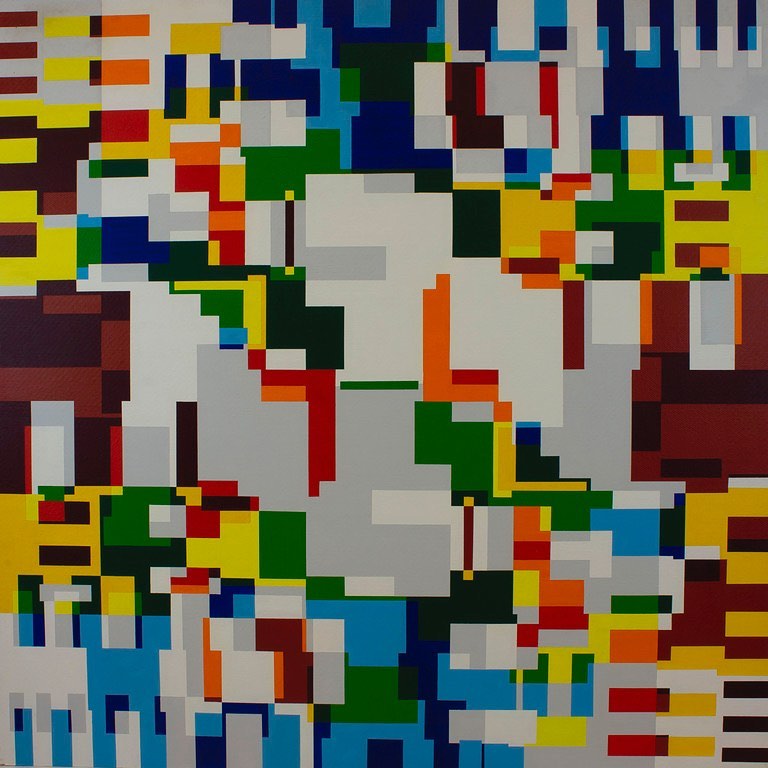

I also checked the visual work by Hoppenbrouwers; paintings titled ‘Harmonic rowes’, ‘Ockeghem I,II’, ‘Diatonic scales, Pythagoras, Equal temperament’, etc.

So I tried to connect with this: listened to Ockeghem, Webern, Xenakis, …, also Coltrane, checked some solos by Steve Lacy, rediscovered Salvatore Sciarrino. So, all this becomes a labyrinth of possibilities and then here’s another obvious consideration: I’ve grown up just after the construction of the building. A time in which there was a strong belief in cultural education. I think Hoppenbrouwers has been an important figure in this context and I think this insight has had a consequence in the way I’ve played the session.

“I need a concrete context.”

But, to come back to your question; you’re right: only when Christophe turns to ‘record’ the sound structures start to come out, nothing is written down in advance or cemented in the head. I only work on possibilities, thinking structures that could be used. These structures always need to be confronted with and adapted to the concrete space and context. The directness of the playing, the reflection of the sound in the concrete space ultimately define the nature of the final composition. You can have as many ideas as you want you will only notice if these ideas work when you’re creating the piece.

I need a concrete context. I can’t sit down behind my desk and start to write. To be honest, it even makes me jealous of ‘real composers’.

I need the lucidity of the moment to actually ‘compose’ the elements of a piece ‘in the moment’. Of course, afterwards I can use these concrete structures to make a new composition out of it too. But to me only when I actually make a sound, the urgency to set something against it comes up, that’s how music works for me.

It’s an advantage but it’s also a disadvantage. It’s an advantage, because it can make music more ‘fresh’, on the other hand as an improviser you always need to be careful: not to get stuck in your own clichés, that’s the danger!

Did you record only inside or also outside?

The fifth track of the record has been recorded on the terrace outside of the building. The nature park is on this side of the building. You can hear the overall sound of the environment, mixed with the saxophone, playing outside, mostly inside of the building. To me, this is without any doubt the pedal point of the work. In this track everything comes together very organically and harmonically. The recording session in this track has completely been turned inside out. A kind of implosion has taken place. The outside of the building becomes the inside and vice versa.

Is this like a live album, but without a public? The album is made in one day. Why? Why just in one day?

In a live performance you only have one chance: when the concert starts there’s no way back. It starts to happen when you get on stage and finishes when your time is over. This wasn’t exactly the case here. But Christophe decided from the beginning on to record only one day.

I think this has been a good decision too. Christophe was convinced it would work. It created a similar feeling of urgency as in the context of a live performance, …but somehow different too: not everything that would be played would have to become part of the final piece. So we had some time to try things out. And both of us knew of course that if the one-day recording wouldn’t have been good enough we could have gone back to start all over again but this would probably have felt like a kind of defeat, which doesn’t mean that the actual result couldn’t have been as ‘good’ as it is now. Anyway, I’m happy we did the job in one day.

I also think the story has been told – we don’t need to go back for more recordings. The picture has been made: one recording by one musician in one place in one day.

“The problem with music is that it’s in the air, when you play it, once the music has been played, it’s gone!”

What’s the importance of solo playing in your musical practice?

Very important. It’s a daily practice and it never stops!

I have been playing the saxophone seriously since long ago – and professionally for more than twenty years. It’s a constant struggle, a never ending search for new ways to play the instrument.

At a certain point in my life I felt the need to document this solitary practice. The problem with music is that it’s in the air, when you play it, once the music has been played, it’s gone! All the sounds have disappeared. After some years of seriously playing the saxophone and almost without any valuable traces left behind this became somehow frustrating. I decided to document what I was doing, …

Then came the question: where to record – how to record – how to document ?

Does it have to be a live or studio recording, should all the material be recorded in one place, what’s the ideal context to record the alto saxophone: a church, a live set, a studio? Is it good to manipulate the sound? What’s the difference between a live performance and a recording and how to deal with that? What microphone should you use? This kind of questions…

If you change one of the mentioned aspects the whole work will completely change.

Not only the way the instrument is being played is crucial, the acoustics of the space where the music is recorded, the recording tool and medium determine the music.

Which solo work do you like?

I’ve always loved solo-recordings. I’ve listened for decades to solos by Thelonious Monk, Anthony Braxton, Kayhan Kalhor, Elliot Sharp, Munir Bachir, Hans Reichel, Peter Evans, Ikue Mori, John Fahey and Autechre, always a duo of course but you could consider them as one entity…

I like the tenacity of the solo!

When the music stays in one specific register i.e. the range of only one instrument, it becomes somehow less spectacular. But there’s a dry, almost theoretic, stoic side in the solo that I really like. I also like composed music that is restricted to only one instrument or family of instruments: Schoenberg’s klavierstucke and string quartets, Beethoven’s sonatas, George Lewis’s ‘Toneburst, piece for three trombones’… compositions for solo harpsichord or for organ too!

I have to mention this extremely interesting work ‘Say No More’ and ‘Tongue Tied’ by Bob Ostertag: he asked some of the most interesting solo musicians -Gerry Hemingway, Joey Barron, Mark Dresser and Phil Minton- to send him a solo. Afterwards he made compositions by superposing their solo tracks, cutting and pasting, it became a new composition, being played by the same musicians. Recently, in 2016, he made a new piece called ‘A Book of Hours’ in the same way: three vocalists -Theo Bleckmann, Shelley Hirsch and Phil Minton- join the fantastic solos by Roscoe Mitchell! Here we’re already on another track: the solos become part of a new orchestral piece, but the whole project starts from the concept of solo work!

How did the recording tools determine the Westrand recording in comparison with previous solo-projects?

In 2019 my first solo-work INERTIA was released on the Brazilian label Seminal Records.

It contains a mixture of experimental recordings with the portable recorder (which -by the way- was recommended to me by Christophe Albertijn too!), four studio recordings, as well as one ensemble piece. Most of the work has been recorded in the context of a residency on Isola Comacina (Como, Italy, 2014) sponsored by the Flemish community. It’s quite extreme and complex work. In most of the tracks the saxophone is recorded from very close, often the sounds are almost whispered into the microphones, panned left and right. As a counterpoint to this aspect of the album, I decided to alternate the portable recorded tracks with four studio-versions of my project ‘Stackmemory’, an experiment in which a semi-composed piece is re-sampled over and over, functioning as a live-score to improvise on, until the music reaches a dense orchestral sound with 6 to 7 layers on top of each other. I worked for a very long time on the construction of the overall piece and am still happy with the result. The composition still fits very tightly together.

INERTIA begins and ends with a church recording, exploring the ‘sacral’ acoustics of the little Baroque church Chiesa di San Giovanni Battista situated on the Island. The Westrand project is in fact a next step into this research on amplification, and has to be considered as a dialogue between the building’s acoustics and the saxophone, documented by the recording material.

Westrand is -in fact- less a solo-project than INERTIA. The day we recorded we were in fact three: Christophe Albertijn, Alfons Hoppenbrouwers and me. Westrand sounds much more homogeneous than INERTIA: it’s a monochrome soundscape, a documentary of the acoustic possibilities of the space for alto saxophone. The instrument is recorded in different spaces but each time by the same recording material, on the other hand each time from another viewpoint, another angle (camera position) in space. Therefore you can really call it a documentary of the acoustics of the spaces!

Despite the complexity of track 05 this new solo-album has -in my opinion- much less contradictions in it compared to INERTIA, which is full of baroque counterpoints and ornaments. INERTIA also contains quite some humor, irony, even sarcasm. Westrand on the contrary is a stoic, serene work, completely the opposite of ‘baroque’, contemplative, even metaphysical, it sounds desolate and airy. In a certain way it even reminds me of some ECM recordings, it also makes me think of Tarkowski’s movie ‘Stalker’…

Anyway, it’s the modernist building that made us record and play like this!

INERTIA and Westrand have – apart from the acoustic research on reverberation, another aspect in common. The aspect of field recording, reference to Musique Concrète is apparent in both. In INERTIA ‘background’ noise and saxophone sounds are constantly mixed up; often you can hear the overall sounds of daily life and nature. But there’s one important distinction: in INERTIA these sounds go in all directions, different acoustic contexts are set against each other, there’s not one main focus, it’s not a monochrome. Westrand on the contrary is a gently changing monochrome, just like the building is one. The album is a compilation of different auditive viewpoints on the concrete inside and outside of the building. A concrete soundblock in six chapters. It’s a meditative contemplation of the acoustic atmosphere in the building.

Is this music without overdubs? Is there done much editing in these recordings?

Christophe made the selection, for some tracks he decided to end the track at some point. There are no overdubs – in contrast with INERTIA which is filled with quite some live and copy pasted overdubs. In Westrand no abrupt changes or switches from one direction to the other.

How much material did you record on this one day?

I think we recorded at least two hours in total. Christophe made the selection of the tracks.

I was happy with the selection of Christophe, just had to put the sequences in an order that made the most sense. Christophe liked the order. It all evolved -in contrast to my previous solo-adventure- very smooth; I worked for five years on INERTIA! Two weeks after the recordings of Westrand the record has already been released!

“Complete freedom doesn’t exist.”

What does freedom mean in your practice? And how is it related to chaos? Is ‘playing’ the same as ‘practicing’? Is ‘playing’ the same as having fun? Here’s a quote: “Freedom without discipline is chaos” (Art Blakey).

Art Blakey was an incredible virtuoso player and a real sound architect. His solos are extremely balanced. In each one of his solos he carefully builds up a tension until the point where it gets to a perfect climax – then he starts to play with the rests and silences. And then he rebuilds up the tension. There’s an incredible amount of logic and structure in his playing. He’s an extremely disciplined player. Knows exactly what he’s doing: all the time…

As a musician you’re always restricted to something: the instrument you use, the place in which you play etc, you have to deal with the situation you’re in.

Complete freedom doesn’t exist.

When you play one sound you’ve already produced a restriction, because then you have to choose which will be the next one and when to play. That’s a serious decision. Hopefully the right gesture will come out. Otherwise you will have to deal with that and you will have to try to make meaning out of the thing that went wrong. That’s no problem. That’s the way improvisation works. Doesn’t matter if it’s wrong. You don’t have any choice, you have to go on. You can’t choose chaos, you can only use the restrictions and create the restrictions of the composition. Therefore you need discipline. And discipline isn’t only technique…

All this sounds serious, but in fact; it’s fun! But at the same time it’s also serious. Good humor is serious. Good music too.

To put it in relation to the Westrand recording: the acoustics of the space offer great opportunities, but the sound of the instrument is also restricted by the same space. If you play at Westrand you will have to deal with the reverberation. If you play for example in a dry room you’re in a totally different sound space with other restrictions but also other opportunities. As I said earlier, sometimes you know in advance it will be difficult to play in certain acoustics, sometimes you get a sense of freedom, even before you start. But anyway, it will be difficult, even if it starts smoothly.

To put in relation to the instrument: if you play the alto, you don’t play the tenor. If you play an old conn, you don’t play a Selmer or Yamaha or… These are all restrictions.

Why did you choose the saxophone? And why the alto, why not the tenor?

Why the alto? Sometimes I consider to try out the tenor, or even the baritone or bass clarinet or even the fagot!, but until now I never came to that point.

For me there’s still so much work on the alto! Charlie Parker played the tenor perfectly, he could also switch instrument whenever he needed, Ornette Coleman at a certain point switched to the tenor, he even played violin and trumpet, or the suono; there’s an incredible record called ‘Bouddha Blues’ of Ornette Coleman playing the suono, a kind of wooden oboe, it’s a great instrument, and it’s a rare recording in Coleman’s career. Coltrane apparently wanted to switch to the alto just before he died, he developed a personal soprano technique, but to me he stays a real tenor player but he started on alto, there’s an excerpt on Youtube of Coltrane, playing the alto. Dolphy is definitely a real alto player but he also played the flute, bass clarinet, etc a real multi-instrumentalist!

I guess I will never be a multi-instrumentalist, too late for that, I admire saxophone players such as Anthony Braxton, Roscoe Mitchell or Peter Brötzmann but I couldn’t manage this bunch of work, switching from one instrument to the other like Rashaan Roland Kirk did… technically it would become too difficult, although I never tried… As I said, for me there’s still too much work on the alto… I think Steve Lacy always played the soprano, never switched to any other saxophone, maybe I’m a bit like him. But his technique was of course much better than mine. Anyway, I’ve chosen the alto…

Then if you think of multi-instrumentalists, most of them still have their main instrument too. To me Braxton’s main instrument is the alto! Maybe Roscoe Mitchell’s main instrument is the alto too, Eric Dolphy is without any doubt an alto player, but almost in every record he switches to flute and bass clarinet. Evan Parker has two sides: the tenor and soprano side, just like Coltrane: that’s what’s great, when every instrument of the family makes you play differently; that’s the point where it becomes interesting! Johnny Hodges was a real alto player – Paul Desmond was a pure alto player too. John Tchicai switched to tenor at a certain point in his career, quite interesting because he was a real alto player, maybe Lester Young played the tenor somehow as an alto?

I will always stay an alto player. Perhaps it has to do with the timbre of the voice. My voice isn’t that low. I’m more in between the alto and the tenor. That’s what I like about the alto, this in betweenness: the instrument can sound high, but it can go very low too. I like the lower register of the alto. I like to play the alto and sound almost like a tenor. I also like the lower sounds of the alto when Braxton is playing them, so strong!

One day I also considered playing the C-melody, a rare saxophone in between the alto and the tenor. In 15 years or so I could go back to Westrand and do a new recording. How would the record sound with a C melody or a tenor?

When did you start to play music? Why did you choose the saxophone ? What training or education did you have to master your instrument?

My oldest brother played the piano, my second brother played the double bass. As kids we were really into Jazz (Thelonious Monk, Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane were always around. Especially Monk, we had more than twenty records of him!). So, I could have chosen the drums but it seems to have been always clear that I would play the saxophone.

I started on sopranino, then switched to soprano and have been following music school at the academy of Vilvoorde: at some point I had a new saxophone teacher. I was so jealous when I heard him play his scales so fastly each time I arrived. He was a real virtuoso and I couldn’t play a note! Before him I had another teacher, I don’t remember his name, anyway it was a real nobody, he didn’t know anything about the saxophone.

My new teacher advised me to switch to the alto. He told me I was talented but he was very tough. He also told me that the things I had learned from the previous teacher were completely wrong, that I would have to start all over again!

Sometimes I was crying when I left his class, he yelled at me, he pressed his thumb to my chin while I was playing, in order to learn how to keep the mouthpiece tight in the mouth. One day I took this Coltrane record ‘Kulu Se Mama’ with me and told him I wanted to play like J.C.. He looked at me briefly, thought he smiled for a while then said that I had to learn to play the saxophone first. And of course he was right. But I’ve always been headstrong. I knew I wanted to learn to play the saxophone in another way, didn’t know how but knew someday I would… Playing the saxophone has been a real struggle when I was a kid. Sometimes I was crying just because the playing really didn’t work. I felt hopeless!

After having finished the solmisation cyclus of five years, I quit. But still had the alto.

I stopped playing when I was about 13, I guess. At the age of nineteen, after having listened for the first time in my life to ‘A Love Supreme’ -I know it’s a ciché but it’s true- I went up the stairs and took the saxophone out of his box and started to play again!

Then one day I went to a concert with the great Eddy Loozen playing the piano in a quartet with Peter Jacquemyn (my uncle) on double bass, Ivo Vander Borght on percussion and André Goudbeek on alto sax. Peter introduced me to André, and said I wanted to learn to play the alto. That’s where it all started. It changed my life! Together with André I bought the old conn alto saxophone I’m still playing now. I will never forget how we entered the music shop, started to play on a bunch of alto’s and finally decided to buy this one. It was just love at first sight. This would become my instrument!

However, I did not take much lessons with André, not more than seven I guess but that’s where it all really started for me. That’s where I learned how to find my own way to work on the instrument. So, back then I decided to become a real saxophone player, followed the improvisation courses with Garret List at the Conservatoire royal de Liège and started to play in the most diverse contexts. That’s how I developed my own technique and found my own voice. By playing in completely different situations with completely different musicians.

In essence I still consider myself as a real autodidact. Although I learned a lot from different teachers I always kept on developing my own sound and techniques: by trial and error.

Should it be an artist’s goal to ‘get better’, or should the goal be ‘trying to find your own voice’?

Perhaps I got better over the years. Anyway I’ve changed, that’s already something.

I keep on working on my sound, that’s for sure and I’ve still some techniques to learn. And some things I did in the past aren’t repeatable… I may have been playing ‘better’ in the past too… virtuosity can become a jail too! Even when you’re a virtuoso player you’re restricted… perhaps even more. Maybe this could be a definition of the discipline you need; To play the right note whenever you need to and not to play when there’s no need to play, and to stop playing when there’s nothing left to say! Just like Thelonious Monk did…

And for each project you will have to search for a new voice, try to deal with the chaos that precedes it and make something out of it. You will always have to go back to things you did before. You can’t create out of nothing. Also, this process isn’t straight-lined, it’s more like a cyclic process. Ideas and techniques from fifteen years ago may reappear, but you will have to adapt them to a new context. In consequence, the ideas have to be transformed…

This process never stops. It’s a daily practice, even if I don’t play, the inner conversation about how to play is always continuing…

The album is called ‘Westrand’ because it’s recorded at Westrand, Dilbeek. Why?

I think it’s just a simple way to give the record a name as a document. The place, the architecture, name of the building where the music has been recorded, is also the name of the album. If there’s a double meaning we should ask Christophe. The whole project and record label HUIS is Christophe’s masterplan!

Joeri Bruyninckx

Christophe Albertijn Official Website

Huis Bandcamp | All proceeds from HUIS Bandcamp sale goes directly to the musicians