This Heat | Interview | Charles Hayward

Charles Hayward is known as the pioneering drummer with exceptional This Heat and Camberwell Now.

In 1976, Charles Hayward of Gong (and Phil Manzanera’s Quiet Sun) joined with Charles Bullen and Gareth Williams to form This Heat. Though arising from art-rock and the British school of fusion jazz, This Heat quickly developed into an experimental band largely dependent on tape loops and production tricks. The Camberwell Now was formed after the breakup of This Heat. Charles Hayward also played with Mal Dean’s Amazing Band, Dolphin Logic, and gigged and recorded with Phil Manzanera in the group Quiet Sun as well as a short stint with Gong and much more.

To begin with, when and where were you born and was music a big part of life in Hayward household?

Charles Hayward: I was born in south London at the end of 1951 and lived in Camberwell until I left the family home and moved to Deptford in 1976, where I still live. Music was always a big part of life at home, my father especially was a big music fan, an active listener, although he couldn’t play an instrument. He had a fantastic collection of jazz 78’s, Duke Ellington, Teddy Wilson, Ella Fitzgerald and Coleman Hawkins were particular favourites. I remember one Sunday afternoon my father becoming transported by Ella singing ‘Everytime We Say Goodbye,’ this everyday guy suddenly looking off into the far distance with misty eyes. That song, ‘how strange the change from major to minor’ was so important to me, still is, love that simple change of a chord from minor to major. My mother played piano badly, “busking” the left hand by moving up and down rhythmically. When I worked out that she was just playing clusters it really helped me understand how so much of music is implication, the listener does the work. Big lesson, especially aged 10 or 11.

At what age did you begin playing music and what were the first instruments that you played?

Family story was that I played pots and pans on the kitchen floor when I was 18 months old. I started piano lessons at 4 years old but also had small things like whistles and toy xylophones which I found little things on, certain notes would sound better than others and I’d build things with those. I got my first drum kit for Christmas aged 10 and still use one of the drums from that first kit.

“It was far out and crazily adolescent rebel music”

What were your first musical involvements?

From the age of 11 or 12 I kept trying to get groups together but they were all dismal failures, usually one rehearsal and everybody else would start playing football or watching TV; it drove me crazy. But there were a couple of piano recitals, a school play where I devised the music, basically atmospheric drum solos, and lots of extreme jamming with my younger brother, Tony. He played guitar which he never ever learned to tune, he just used it as a noise generator. The Who’s ‘Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere’ was a big influence, especially the middle “noise” section, so we played like that but without any song before or after. Looking back it sounded like the album I made with Thurston Moore or something with Keiji Haino. I wish I could find one of the scruffy tapes we made and get it transferred, it was far out and crazily adolescent rebel music, the real thing.

You attended Dulwich College. Bill MacCormick (interview here) said the following: “The band Phil and I formed in late 1967 (I was the singer) was called (courtesy of my brother) Pooh and the Ostrich Feather. We messed about a lot with various other guys until someone told us about a young man in the year below who had his own drum kit. His name was Charles Hayward. We invited him round to Phil’s mum’s house where he set up a huge, red glitter, double bass drum Premier kit. He immediately became a member of the band. Charles was already a great drummer having been given lessons for some time.” Can you elaborate on the formation of the band?

Not much more to say other than it was like meeting soul mates and massively enjoyable. We did a lot of laughing as well as a lot of learning and it was always serious fun, as George Clinton would say. We played some sort of poetry club school event, a thing called Muse that Bill’s brother Ian set up. I think the first song we did was ‘Born in Chicago’ which we heard from James Cotton, I think. It was either that or Phil’s tune ‘Dangeranium’ with Ian lyrics, more like an 8 bar chord riff, very basic/raw but with wild rocking out, and everybody into it, much more important than technique. Not sure what else we played.

“There was one gig at the Methodist Hall, Half Moon Lane, the audience was a revelation, first time I really felt the link between the band and the crowd, I have always aimed for that ever since”

When and where did Quiet Sun play their first gig? Do you remember the first song the band played? How was the band accepted by the audience? What sort of venues did Quiet Sun play early on? Where were they located?

We played outside London once, every other time was in this small area of south east London around Dulwich, Catford, Norwood, Herne Hill and pretty much DIY gigs that mates promoted. The first tune might have been a longer version of what became ‘Mummy was an Asteroid’. The audiences always seemed to like us, we were part of this little local scene and the fact that we were so musically ambitious and tight meant they were very supportive. There was one gig at the Methodist Hall, Half Moon Lane, the audience was a revelation, first time I really felt the link between the band and the crowd, I have always aimed for that ever since.

How did you decide to use the name ‘Quiet Sun’?

It was either a Thomas M. Disch or Philip K. Dick story, we had a whole list of them and we’d walk around saying them out loud just to feel what they felt like to say.

What influenced the band’s sound?

Spirit, Soft Machine, Terry Riley, Ornette Coleman, Velvet Underground, Erik Satie, (The Tony Williams) Lifetime.

Quiet Sun disbanded in 1971. If I’m not mistaken, Phil Manzanera invited you and other members of Quiet Sun to create the album you always wanted to. What were you doing between 1971 and 1975? What are some of the strongest memories from recording the ‘Mainstream‘ album?

Between 1971 and 1975 I did what a lot of young musicians did at that time, answering adverts in the back of Melody Maker for musician auditions, did a lot of that. I met the trumpeter and illustrator Mal Dean, he was the leader of Amazing Band, which was one of the first truly European free improvisation groups, breaking away from the jazz model and without any tunes, complete improvisation, and ended up playing with them for 18 months or so. We did a session for Radio 3. I worked on songwriting and developed early versions of Not Waving, Makeshift Swahili, Fall of Saigon, Twilight Furniture, Sitcom, The Ghost Trade which later were part of This Heat and Camberwell Now music. For a couple of months in 1972 I was drummer with Gong which was like a long dream, learning a lot about music making and about myself, a big learning experience. Daevid Allen (interview here) was wonderful, funny, imaginative, inspiring. But I decided I definitely wanted to write and perform my own material and needed to move on to be able to do that. When my Dad met me at the airport he only recognised me because I was sitting next to my drum kit. Also I met Charles Bullen and started working on things with him. Some of it was open improvisation, we called ourselves Dolphin Logic, other stuff was more written electric stuff and we worked our way through various combinations with other people but nothing really jelled.

How was working with Brian Eno?

Really good, he seemed to be always connected to what was going on, seeing the possibilities in the peripheral, shifting the focus. He’d just developed Oblique Strategies with Peter Schmidt, a big memory is him walking around the studio with huge ears he’d made from kitchen tin foil.

Please share your recollections of the sessions. What were the influences and inspirations for the songs recorded?

I was just so happy to be in such an amazing studio as the Island Studios at Basing Street and with Rhett Davies engineering and to have 2 weeks to make something. We’d start at 7 pm after Phil had already spent a full day recording ‘Diamond Head’ and go on until midnight. Our main preoccupation was to rework the music to accommodate the things we’d learned since we’d last played together, which for me was mostly about attitude and how that changed the muscular thing, the actual intensity of the drum stroke, plus I’d integrated new sounds into the kit and I understood what I was doing better. We also edited some of the pieces, made them less fiddly and over complex, I’m so glad we did that, and made the record still listenable, I think. Plus we recorded my song ‘Rongwrong’ which we never played live, it was the next thing we were going to work on before we split, so building that from a totally studio point of view was a new thing for me. I loved it.

How pleased was the band with the sound of the album? What, if anything, would you like to have been different from the finished product?

I like the sound. For what it is and how it was made I pretty much think it still works, it got some sort of pre-punk aggression going, a sort of stark oxy-acetylene in monochrome vibe. I don’t really think of records as things I’d change, the process of making them turns them into a series of inevitable events that accumulate into a finished thing, similar to a tree or a cloud or a mountain. Once they’re made I just listen to them so I can make the next thing continue or disrupt the line from one record to the next.

“I was 20 years old, I took acid, I smoked pot incessantly, I lost weight and my virginity, my beard was ferocious and my freak flag was in full bloom. No wonder my Dad didn’t recognise me at the airport”

After the album was out you joined Gong for a few weeks. What are some recollections from the time you spend playing with members of Gong?

No, that’s not right, I was in Gong June/July of 1972. As I said earlier, Daevid was an inspiration, so was Didier and Francis Linon the sound engineer. When I arrived Gilli had just given birth to their son, Talisyn, so she didn’t do the first couple of weeks of gigs. The difference was immediate even though she was only on stage for part of the show at first. The dynamics became much more subtle, like waves as opposed to steps, if you see what I mean. Gong dealt a lot in primal energies in his own way and Gylli’s influence on the music seemed to be at that level. It astounded me. We played one gig on a clifftop looking out over the Mediterranean under a full moon. Selene! Spirit of the moon! That might have been the same gig that Daevid swept the stage with a broom instead of his usual guitar solo on one of the tunes. Didier and I had one long van ride where we talked about off beats on 2 and 4 or just on 3, the depth of his insights into that alone was worth the journey. I was 20 years old, I took acid, I smoked pot incessantly, I lost weight and my virginity, my beard was ferocious and my freak flag was in full bloom. No wonder my Dad didn’t recognise me at the airport.

Around this period came a turning point in your career when you realized that you need to find a way to express your ideas and talents. You met Charles Bullen and started one of a kind project. How did you meet Charles Bullen and what can you tell us about some of the first ideas you had in a pre-This Heat project called Dolphin Logic?

Meeting Charles was a big moment in my life, still is. Charles answered an advert I had put in the Melody Maker looking for a guitarist and bass player. It must have been one hell of an advert. Other musicians who auditioned included David Toop, Percy Jones, John Etheridge (interview here), Billy Jenkins, Brian Turrington. I was working with a sax player at the time and the auditions went nowhere because he wanted John Etheridge and I wanted Charles. Anyway, a few months later we met again at a Keith Tippett gig and I wrote to him suggesting we tried something just as a duo, taking attitude as a starting point instead of thinking about bass, drums, guitar, etc. Just to work with what was at hand. It was completely improvised and we seemed to build our own soundworld from the start. I was using small instruments as well as my drum kit, melodica and whistles for example. It felt like childhood was lurking just beneath the surface of the music. Among our influences were the last scene in the film The Fly and Saturday afternoon horse racing on television.

Does any recording exist?

Yes, there’s a couple of sessions at my parent’s house and a gig somewhere on cassettes. We keep planning to get it released but it doesn’t seem to happen.

Can you explain how you two met Gareth Williams and how all of you decided to form This Heat? What was the concept behind it and what can you tell me about the name of the project?

Gareth worked at a record shop and knew some musicians Charles and I were working with, at first he managed the group Charles and I were in at the time but the group was short lived and he was not really a manager, he was a performer, even off stage. Charles, Bill MacCormick and I were trying to make something, Bill and I had tried once with Phil Miller, they’d both been in Matching Mole, I thought we needed someone to transmit energy from stage to audience, I suggested Gareth, he came over, it didn’t work with Bill, we started making stuff with Gareth. We started working on stuff early 76 and within 3 weeks we played our first gig. We were called Friendly Rifles at first but then Sex Pistols came along so we wanted to change the name. The summer of 76 was one of the hottest on record, so we called ourselves This Heat.

Gareth Williams was a non-musician at first. Did you teach him to play?

Not like we gave him lessons. In fact he taught us a lot by asking questions and by making “mistakes.” I’d been playing drums for 14 years, Charles guitar for 9 or 10, we were surrounded by prog and fusion, technique was overblown to the point where it stuck out of the music, hideous noodling and doodling everywhere, we wanted to pull back from all this self expression and put pure sound to the front. The first few times we played, the nearest thing to it that I had experienced was playing with my brother when I was a kid.

Your first album is absolutely amazing. Industrial rhythms, tape manipulation, unique lyricism and improvisation. Was it difficult to make it or did you already had everything in your mind and the only problem was to record it the way you imagined it?

It felt difficult to get to the point where we could find people to support us, the John Peel show helped and Blackhill agency had a feeling about us and funded us at a low level so we could build our thing. We recorded at Workhouse studios, then we took the mixes away and edited recordings from rehearsals and gigs into the studio recordings. When Rik Walton the studio engineer heard it he barely recognised it. We always thought that we were making records from the very start, recorded everything we did, ‘Rainforest’ on the first record is from our first gig February 13th 1976.

“The space between improvisation and composition fascinates me”

What does improvisation mean to you and to your perception?

Improvisation has been central to what I do even before I knew it was called improvisation, in a way it’s just making sound without needing permission. If there’s other people playing then you make sound together so you don’t all do the same thing and maybe you play less when there’s more people involved. For me it’s always somehow related to the song, or the space before the song perhaps, with full attention on cadence and structure so that at times people think it’s composed. Since This Heat I’ve done a lot of pure improvisation gigs, often with long term projects and people often ask who wrote the music and find it difficult to believe we make it in the moment. Music manipulates time, when players are in tune with the totality things fall into place. The space between improvisation and composition fascinates me. It also is a model for social exchange and organisation and brings the design and execution into the same moment. As our technology becomes faster we are organised within smaller time frames. Improvisation short circuits this and gives control back to the music worker, fusing design, management and assembly floor into the same moment.

What’s the story behind ‘Health and Efficiency’?

I started riding a bike to save money. At first it was a bit strange, Gareth and Charles said “On your bike” like “fuck off” as a joke. I replied ‘Health and Efficiency’ which was the name of a nudist magazine. Meanwhile I was obsessed with the Futurist manifestos and they were full of stuff about optimism and energy and enthusiasm and relating that to the body and to communication and culture in general. I loved the “words-in-freedom” approach of Marinetti, like telegrams but full of poetic synthesis. One day at Cold Storage we basically improvised ‘Health and Efficiency’. I went home that night and wrote the lyrics, we made tapes of the school playground and an improvisation in the large space next to our studio which we used over the long groove section.

‘Deceit’ was released in 1981. How would you compare it to your debut?

We always said that the first album was made from our sense of unconscious dread and Deceit was made from our conscious dread. That’s why there’s much more songs on ‘Deceit,’ with much more lyrics.

What was the concept behind it and what influenced you to record this album?

The Cold War was at its height, mutually assured destruction, consumerism was becoming a way of life, words were mostly lies, freedom/slavery, nuclear war was mirrored by nuclear power. Atomkraft? Nein Danke!

What was the recording process like?

By the time we started making Deceit our process was in full swing with a large archive of recordings, cassette, stereo reel-to-reel, multi-track. For instance we hired a mobile 24 track to record ‘Health And Efficiency’ in Cold Storage and recorded basic tracks for ‘Paper Hats’ and ‘New Kind of Water’ in the same session. We collaged ‘Makeshift Swahili’ from 3 different recordings, ‘Radio Prague’ and ‘Hi Baku Shyo’ were from improvisations, the other songs were recorded at a couple of other studios, we did any overdubs that were needed and then edited into its final shape, similar to how we put the first album together.

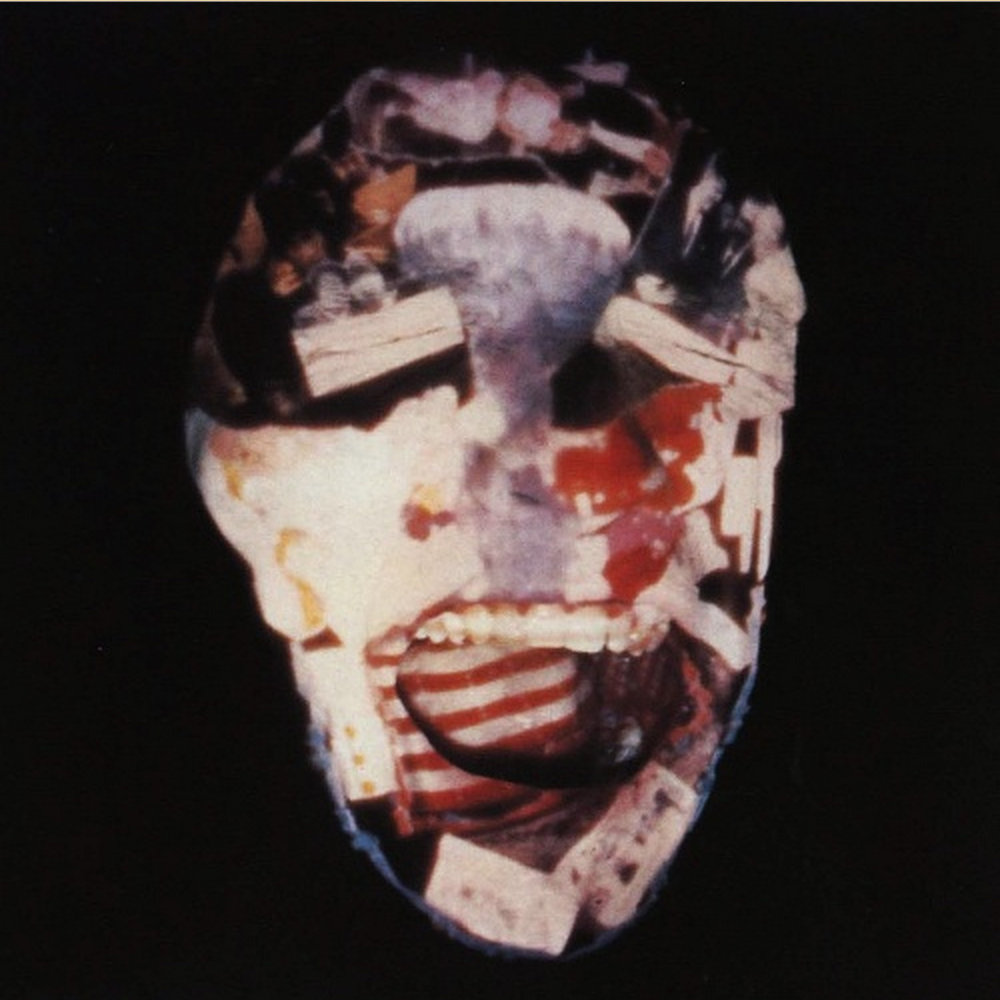

How about the artwork?

Gareth, his partner Nick Goodall (who was a photographer at the National Gallery) and the xerographer Laurie Rae Chamberlain (who had a studio flat upstairs from Cold Storage) worked on the cover together using images from Protect and Survive which was a pamphlet about how to survive a nuclear strike and newspaper photographs of Brezhnev and Reagan, made that into a mask shape, photographed it and projected that photograph onto Gareth’s face and then photographed that again.

Is there any unreleased This Heat material?

There’s reels and reels of improvisations from Cold Storage, we got plans to work them into a shape for release. That’s a while before we finish, we haven’t even started yet.

Now, 40 years later, founding members Charles Bullen / Charles Hayward reunited, with a host of special guests. Can you tell us more about your guest musicians?

We’ve been very lucky working with some amazing musicians. At the very beginning we were a huge group, 13 or 14 players including Thurston Moore, Alexis Taylor and John Edwards. When we started playing festivals in Europe we shaved it down to a 7 piece. Daniel O’Sullivan plays keyboard, bass and vocals, he’s in Grumbling Fur and works solo and on diverse projects. James Sedwards is on guitar, he’s in Thurston’s group, has his own group called Nøught and is an all-round guitar hero, incredibly responsive and focused. Alex Ward plays guitar and clarinet and sings on a couple of songs. He works across pretty much every approach from total improv to total composition and brings a beautiful rigour to the music, very concentrated and meticulous. Frank Byng plays drums, percussion and uses FX on his kit, which has made possible to play a live version of ’24 Track Loop’ which we never thought we’d be able to do, he also frees me up to sing on ‘Cenotaph’ and ‘Independence’. Usually 2 drummers are a nightmare but we’ve never really had a problem playing together which means we have been developing aspects of the material like the end section of ‘Paper Hats’. He’s got a whole thing away from the band too, he runs the Slowfoot record label, he plays, writes and produces with his 2 projects Snorkel and Crackle and runs a very nice studio. Until recently Merlin Nova was in the group, she’s much younger than the rest of us, sings, plays keyboard, violin and percussion. She left last year because she wanted to concentrate on her solo work, which is amazing and way beyond genre, it’s not even just music, it’s performance, dance, video, radio shows, painting. I think she brings something really fresh to the music and I’m very pleased we’ve managed to persuade her to re-join for the final few gigs. The group was only supposed to exist for 6 months but the response and the requests to play throughout the world meant we were together for 3 years. We are still getting offers to play but we have to stop before it becomes some sort of easy thing. The way I see it, people are digging music I made 40 years ago so I better get back to making music for the future.

“Drumming with other people’s projects gives me insights that I can use inside my own work”

After This Heat you did sessions for The Raincoats, as well as for Lora Logic solo album and Everything But The Girl. How was it to collaborate on those projects?

I really enjoyed it and learned a lot. Everything But The Girl was in a proper old style studio, we rehearsed and recorded, maybe it was 4 or 5 days in all. Ben and Tracy had strong ideas about what they wanted and I just developed those ideas. Lora was one weekend in a squat with a studio, I think we did 7 or 8 songs and bounced the drums tracks down to stereo at the end of it all, very fast and immediate, go with the first idea sort of thing but keep an eye on verse chorus structure. The Raincoats was a much deeper thing, we rehearsed and developed the songs, they were big on imagination and pictures in the mind and we worked together to make them into sound. I toured with them in Europe and the UK, too, for 6 months, which was wonderful. I’ve got this thing about different degrees of control in the work, the ideas around improvisation and the executive office and the factory assembly line. So sometimes I just do what I’m told, throughout the 80’s and early 90’s I did a lot of session work including TV drama soundtracks, completely doing what I was asked and not trying to input ideas, like a factory worker. At other times I am responsible for the design of the music and I have a different role. My ideal is to be in all positions at once, either through improvisation or as writer and player. Drumming with other people’s projects gives me insights that I can use inside my own work.

Your next step was forming Camberwell Now with bassist Trefor Goronwy and tape manipulator Stephen Rickard. The trio released 2 EP’s: ‘Meridian’ and ‘Greenfingers’ and ‘The Ghost Trade’ LP through the Swiss Recommended label. How would you compare Camberwell Now to This Heat?

As far as the music goes I really think we were a wonderful group, I just heard a gig from 86 that I thought was some weird studio thing, Stephen was doing things with tape that made the music seem to reach out forever, plus Trefor’s playing was hallucinatory, so many interweaving lines in different registers. I think he was a seriously overlooked player. By the time we started making ‘The Ghost Trade’ I was super tuned in to developing my creative process, the writing was an intense thing, I’d go out into London rush hour and just soak in the endless exhausted, haunted faces, then go to the studio and we’d record through the night. People didn’t seem to pick up on Camberwell Now like they did This Heat. I think there were a lot of reasons. The name of the band, the fact we had no guitar, that we never played a Peel session, that we played the ‘game’ much less than This Heat (Charles and Gareth were always networking, I’m useless at that), that we didn’t have a manager, that our strongest connections were in Europe more than London, I could drive myself crazy going through this list, the time Geoff Travis from Rough Trade told me that the “kids have met their partner, they want to settle down and get a flat, that’s the music we want to release now,” the way Thatcher had put her fingerprints all over the culture, the audience were consumers now and everything else was a loser. So we just didn’t fit at all, everybody was a New Romantic or some such bollocks.

After the trio disbanded in 1987 you actively embarked on your solo career. ‘Survive the Gesture’ was your debut album.

I started writing the songs for ‘Survive the Gesture’ when Camberwell Now was still touring, Stephen wanted to make a change in his life so the band stopped, I was going to be a father too, so it all felt inevitable. The songs reflect these changes, I’d had a few central experiences for the first time, about to become a Dad, the day-to-day of relationships in the modern world, friends dying, the fucked upness from childhood surfacing and needing resolution, the essentially tragicomic quality of everything, the sheer beauty of everything. I love this album, it was made in 10 days, it all seemed to fall into place like it was waiting to be made and all I had to do was go to the studio each day and stand in front of the microphone and build the songs. I managed to get it finished before our son was born which felt important, I knew life was going to be different from then on.

“John Cage in his notes for Musicircus says that in the future music will be either collective improvisation or solo performance because in both those situations nobody tells anybody else what to do”

Many albums followed. What would you say is the main difference in being a solo artist?

John Cage in his notes for Musicircus says that in the future music will be either collective improvisation or solo performance because in both those situations nobody tells anybody else what to do. Working a lot in both those ways I can see what he means, there’s the orthodox way of organising and that seems to always end up with someone telling someone else what to do. So I’ve got to this place where I do the songs solo and use that arena to investigate music and the world from my point in the everything, to present my reality in as direct way as I can, and meanwhile to also make collaborative projects that start as pure improvisation but might well slowly evolve into something more fixed, but mostly with no one telling anyone else what to play. Occasionally that might get to a place where someone will ask someone else to turn up or down, but that’s usually at soundchecks or recordings. So there’s been a series of solo albums which are mostly songs weaved inside pure sound, I’m working on that all the time, there’s always a song I’m working on in my head while I’m living everyday life, the endless rewrite. Some songs take years and years and years to write. But it might move outside of that zone, there’s a piece I’ve developed called ’30 MINUTE SNARE DRUM ROLL’ that is exactly what it says, half an hour of drum roll, it’s says what it is before it starts and you see people slowly realise that that’s what they’re going to get, and then they slowly succumb to the sound, which conjures trains, seagulls, voices, the ocean. I play that in churches, large galleries, warehouses. The few times I’ve done it in standard performance spaces it doesn’t work, the sound is too controlled, basically I’m playing the room. And playing with inside and outside social time, I’ve got a stop watch by me and I play exactly 30 minutes. But I’ve done more group recordings and share the creative space with other artists, About Group with Alexis Taylor, John Coxon and Pat Thomas, Monkey Puzzle Trio with Viv Corringham and Nick Doyne-Ditmas, the Massacre stuff with Fred Frith (interview here) and Bill Laswell. Solo recordings are super intense to see through to completion, ‘ONE BIG ATOM’ was engineered, mixed and edited on a high quality 4 track cassette machine and 3 or 4 mini disc players, it took me 2 and a half years to finish.

It’s absolutely impossible to cover your discography. You appeared on more than 130 albums! What includes your latest involvement? In 2016 you collaborated with Akira Toyonaga and the result was a free improvisation album entitled Punk. Recently you also did a collaboration with Thurston Moore.

Yes, I seem to keep doing duos with guitarists, my brother, Charles Bullen, played duo with Fred a couple of times. I’ve known Akira for a long time now, since the mid-90’s, and we’ve always tried to make time to play together, there’s even a guitar permanently at my studio for when he comes over, we’re good friends, I’ve stayed at his place in Kyoto. We had a bit longer than usual in 2013, he was over for about 10 days so we played a few times, recording to stereo and slowly refining the sound, we selected stuff from the last couple of times and I did a couple of edits and sequenced it. Not many people know it exists, don’t think it’s been reviewed anywhere. The record with Thurston just sort of happened, I’d asked him to play with James Sedwards at Lewisham Arthouse where I sometimes programme events, he asked me to join them for the encore, that went great, then he played some This Is Not This Heat gigs, then we did a Rough Trade thing as a duo and a gig in Italy, the record grew out of that. We did it in the afternoon.

“There’s a new album of songs coming out in May, it’s called ‘Begin Anywhere’”

What currently occupies your life? Any future projects we should expect?

Family stuff has been changing, I’m a grandfather. I’m keeping myself connected to the stuff of life, family, friends, engaging with other people’s creativity, walking, I’ve always done that to feed it back into the music, so much music seems to come from other music, I want it to be totally integrated into everything, to keep it real. And to let the things I learn from music inform how I live day-to-day. There’s a new album of songs coming out in May, it’s called ‘Begin Anywhere,’ it’s mostly voice and piano with minimal additions. I wanted to focus on the voice and the lyrics, and to strip away technique and rely on my simple piano playing, another way of bringing it back to the ear, coming at things from a different angle. There’s a couple of group projects I want to push, there’s a project called V4V with DJ BPM, Nick Doyne-Ditmas and Vern Edwards, a sort of endless remix of itself, like a weird sonic soap opera, very danceable but fractured at the same time. The big thing for me now is to make a group to do my songs, that’s the new thing I have to start from scratch and build, I’ve not let myself do that properly since Camberwell Now, been working in these other ways, but that feels like the biggest challenge on the horizon. I need to be able to develop it constantly so I’m looking for London based musicians for that.

Let’s end this interview with some of your favourite albums. Have you found something new lately you would like to recommend to our readers?

I’ve been digging Housewives, Rattle and Ex-Easter Island Head a lot over the past couple of years, young UK groups, Harmergeddon in a more audio-visual, sound installation meets performance way, Nathan is a genius. In the States there’s Chris Dave, in some ways it’s more about the drums than the music, so I’m clocking that more like research. There’s been a big shift in rhythm coming out from Dilla into a broader place, some of those guys are intriguing me but not sure if it’s completely found itself yet. I’ve been playing with Kwake Bass, I used to teach him, now I’m heavily learning from him, he’s got a whole deep thing with sample triggering from the kit, and his thing interests me, pushing at the edges but keeping it in a social space. There’s a Moritz von Oswald Trio record with Tony Allen, ‘Sounding Lines,’ that came out in 2016, I think, but when you’ve been listening as long as me 3 years ago is like yesterday. If I keep coming back to stuff that’s the real sign someone’s communicating to me.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

The music is it’s own reward, the work is it’s own reward, it’s a privilege to be able to share the music. Thank you. We are entering strange times, stay alert. What we do now will echo into the future.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Charles Hayward | Photo by Lewis Hayward

Charles Hayward Facebook / Twitter / SoundCloud