Cargo: Unearthing a Lost Progressive Rock Rarity from 1973

Formed in the early 1970s Midlands, Cargo left behind no official releases at the time: only a demo acetate, ‘Delivering The Goods,’ recorded in 1973 and lost to history for half a century.

Andrew Clyde, the band’s principal writer, describes the recordings with a mixture of pride and regret. “We realised by then that we would only have time to play each song once,” he recalls. “It is, effectively, a ‘live’ album.” Paying for studio time themselves, the band recorded under severe constraints, mistakes baked permanently into the tape. Decades later, Clyde admits he was tempted to “do all sorts of digital wizardry… to isolate the vocal and ‘tune’ it,” but ultimately resisted. “Sanity prevailed and we left them EXACTLY how they were recorded, faults and all.”

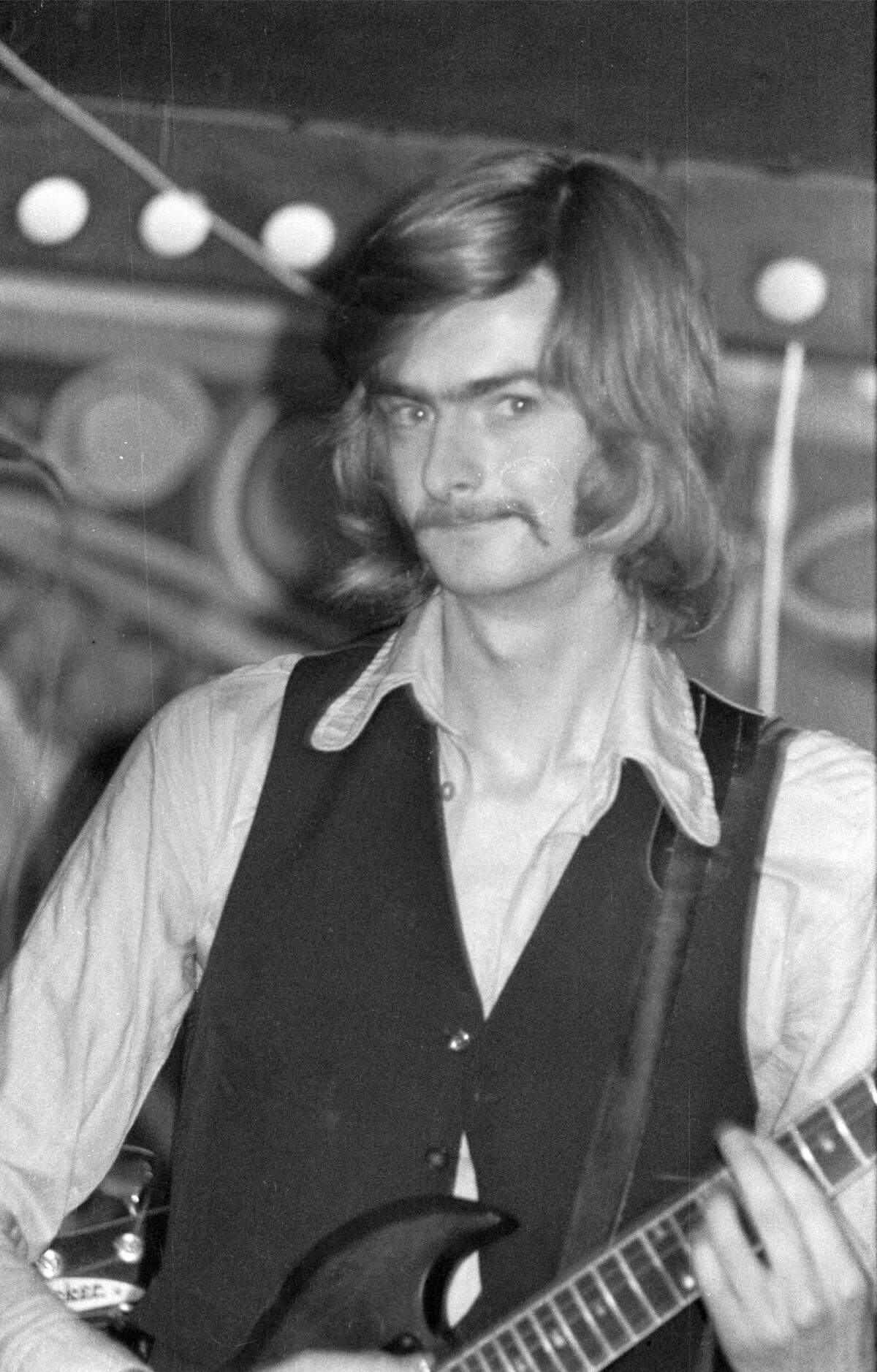

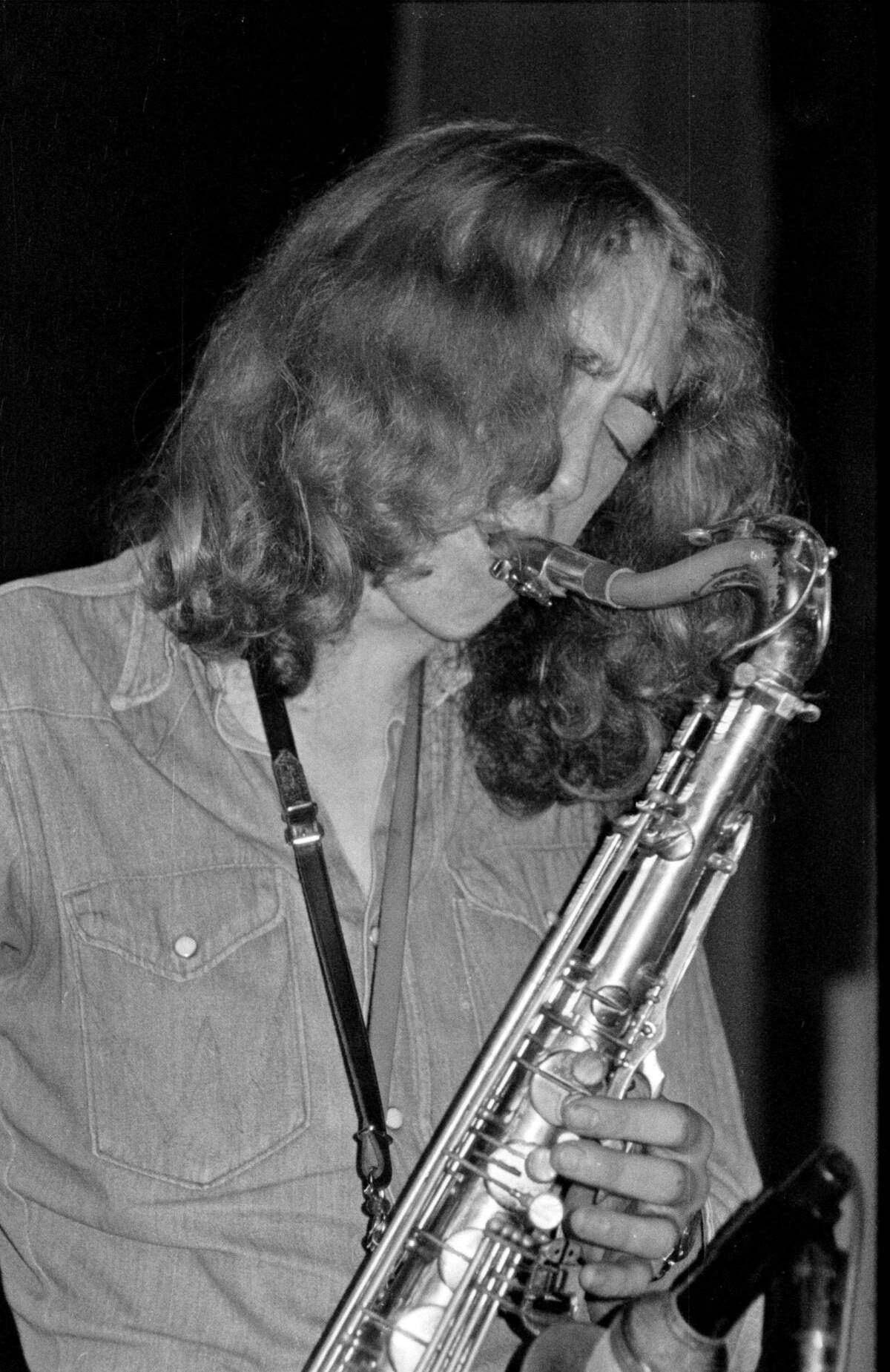

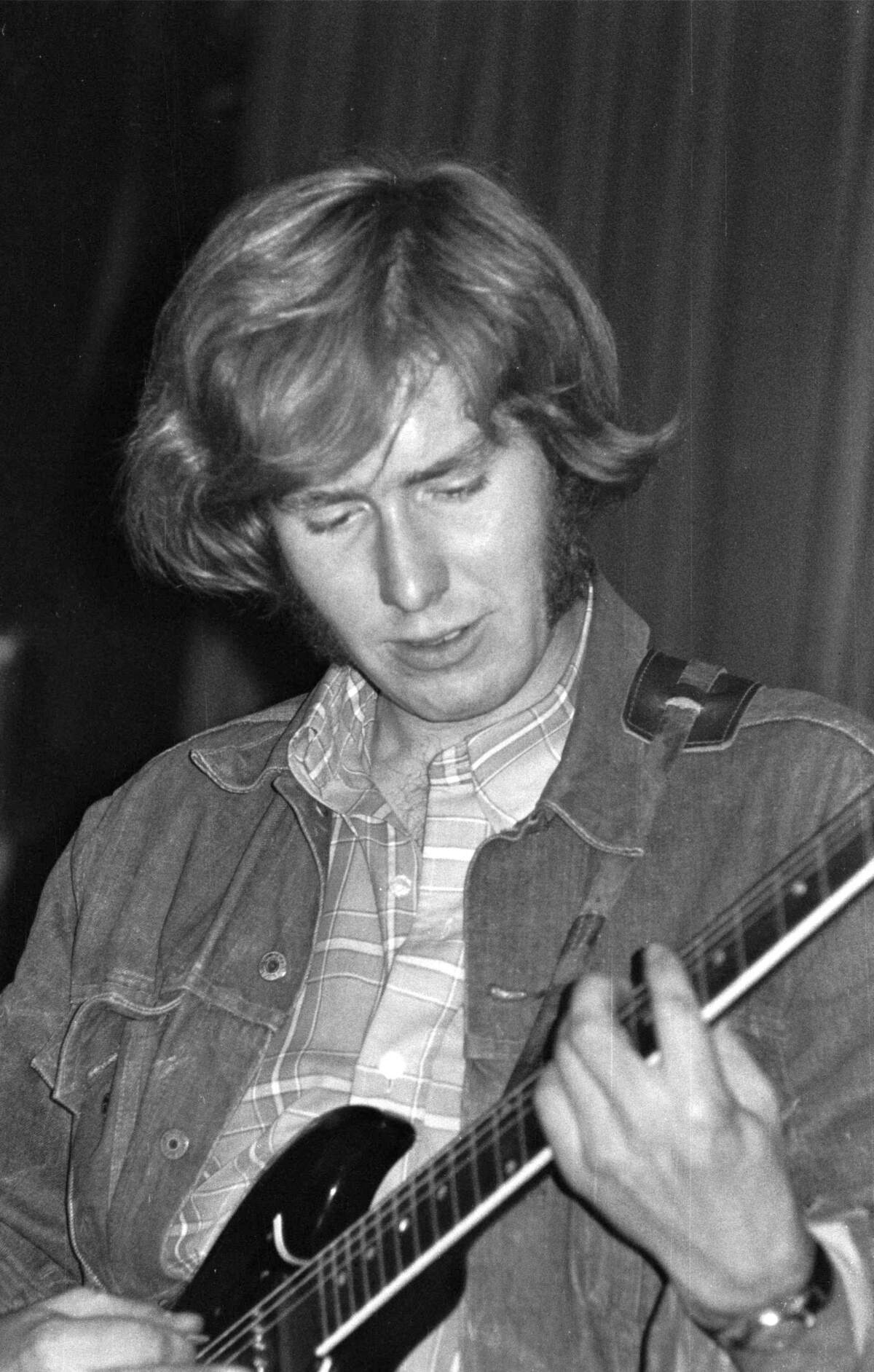

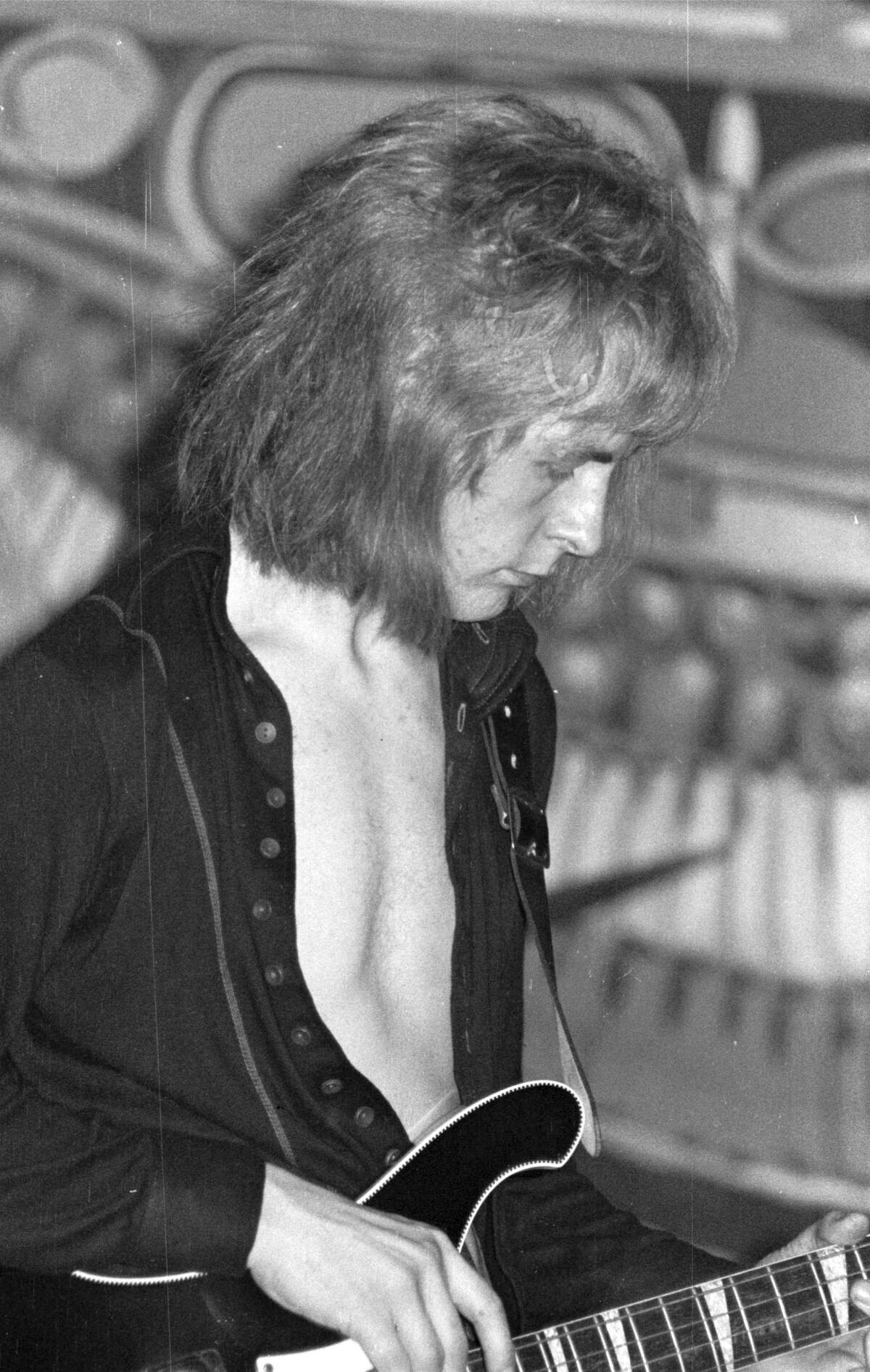

Cargo’s sound draws from obvious early-70s sources, … odd metres, muscular blues phrasing, exploratory saxophone, but it never quite settles into genre. Clyde speaks of “experimenting with time signatures and dissonance and wordplay,” and the music bears that restless intent. Drummer Graham Hair, whom Clyde calls “frickin’ phenomenal,” drives the band like someone permanently late for something important. Guitarist Neillian “Sped” Spedding plays with a sharp, unvarnished attack that suggests neither blues orthodoxy nor prog decorum, but something more urgent and unresolved.

The band’s brief flirtation with the industry ended predictably. Island Records expressed interest, but only in splitting the group. “Being young, inexperienced and foolish, we declined,” Clyde says. “It was all or nothing. So it was nothing.”

What survives, half a century on, is, as Clyde puts it, “the vitality, the energy, the excitement.” Cargo didn’t get the future they imagined, but ‘Delivering The Goods’ finally confirms what the acetate always suggested: this was a band that should have had an album out in the 1970s and now, belatedly, does.

Could you start by telling us a little about your personal roots? Where did you grow up, and what was life like for you back then?

Andrew Clyde: I was born in 1948 in Smethwick, which was a town but is now a region in the conurbation known as the West Midlands. We didn’t live there long before moving out to the country, to a tiny hamlet called Little Hay. Because the schools were very rural, when we later moved to a city Lichfield, it was quickly discovered that my education was approximately one year behind my new classmates. As a consequence, I was held back for a year. This meant I never reached the top class that one should take before graduating to secondary school at 11.

Despite this, I managed to pass my 11-plus exam and graduated to King Edward VI Grammar School in Lichfield. I now know (didn’t really know anything back then) that this was because I have an IQ of 157. I didn’t find this out until I was in my thirties.

Anyhow—I hated my time there and finally left with outstandingly mediocre qualifications.

While there, I was fortunate to meet a fellow rebel and loner named Jeremy Spencer, who later joined Fleetwood Mac in the Peter Green years. In between lessons and during the lunch hour in the cloakrooms, he would play phenomenal honky-tonk and blues piano, and I would strum along on my £4 guitar. I bought it with the proceeds from my newspaper round and my Sunday morning car-cleaning business, and I am completely self-taught. It was Russian (I didn’t know any better) and had steel strings like copper water pipes. This caused my left hand and fingers to become incredibly strong, which came in very handy when I later taught myself to play the bass as well.

Shifting to music, what was the local scene like in your teenage years? Were there specific venues or bands that defined it?

My very first influencer was Hank Williams. I took a girl to the “pictures,” as we called the cinema back then, simply because I wanted to, well, you know. Anyhow, by chance, the movie was ‘Your Cheatin’ Heart’ (1964), and I became enchanted. The local music store had Hank Williams songbooks in stock, so I bought all three and learned them all off by heart. I couldn’t read the dots, but they had chord symbols above the stave and the lyrics.

I got into a lot of trouble at the local Folk Club because they didn’t like Country and Western, so I started playing filthy rugby songs that I had learned. Didn’t go down well!!!

Every great band has a lineage. Before the formation of Cargo, did you play in any other groups? If so, what were they called, and what did those very early days look like? I would love to hear about Helter Skelter… What’s the story there? Did they record anything?

Yessir. I played in all sorts of groups (we didn’t call them bands back then). I played washboard, which I made myself, with a bulb horn, hubcap, bicycle bell, etc. attached in a jug band (1920s Bessie Smith, etc.), several Shadows copycat groups, and notably Yellow Tricycle Roadshow. We played soul and R’n’B. I played bass.

We auditioned for and won a contract with Mecca Leisure Ltd. to tour US Army bases in Germany. There are waaaay too many stories to include here, but if we ever get to share a few beers, I will regale you with them. Let’s just say I gained a vast number of experiences.

By this time, I had joined the Musicians’ Union and, through that organisation, started to pick up gigs as a stand-in for other groups whose members fell ill or went on vacation. I would show up with my Aria Pro II guitar and Fender amp, never having met them before, and position myself by the pianist/keyboard player. They would yell which key the next song was in, and then off we went, with me winging it. My ear and improvisation ability improved immeasurably, as you may imagine.

I moved to Leicester to join a band called Barabbas, which was much more rock- and jazzy-blues-oriented. We were together for a couple of years, sharing a flat in Wigston (a suburb of Leicester) and touring clubs and pubs. When I left, I bought their van from them, Doris the Morris, and fitted it with a carpet, wardrobe, chest of drawers, and a bed. I lived in that thing for about two years.

During this time, I joined a harmony group called Notation, doing Frankie Valli covers, etc. The young drummer had a stunningly beautiful older sister who, 55 years later, is now my wife. (Did I mention that I am an incredibly lucky guy!)

I barely remember Helter Skelter, as they broke up almost immediately after I joined. It had been coming for some time, apparently, but of course I didn’t know that. Only Sped and Nala were in Helter Skelter.

How did you originally meet the other members of Cargo? And what was the initial concept or founding idea behind the band? What inspired the name Cargo?

Anyhow, it was during this period that I had become very taken with the likes of Emerson, Lake & Palmer, Deep Purple, Yes, King Crimson, etc. I fell in love with the idea of experimenting with time signatures, dissonance, and wordplay. It was during this time, living in Doris, that I had a burst of creativity and wrote all the songs that are on the album.

Having briefly met Sped and Nala and realising how super-talented they were, and because I had already encountered Graham Hair on the circuit (he was frickin’ phenomenal, by the way). I approached them to see if they would like to form a group. I think Nala suggested Dave Kent, whom I didn’t know, and we asked him to join because not only was he pretty good, but he had a Rickenbacker!!

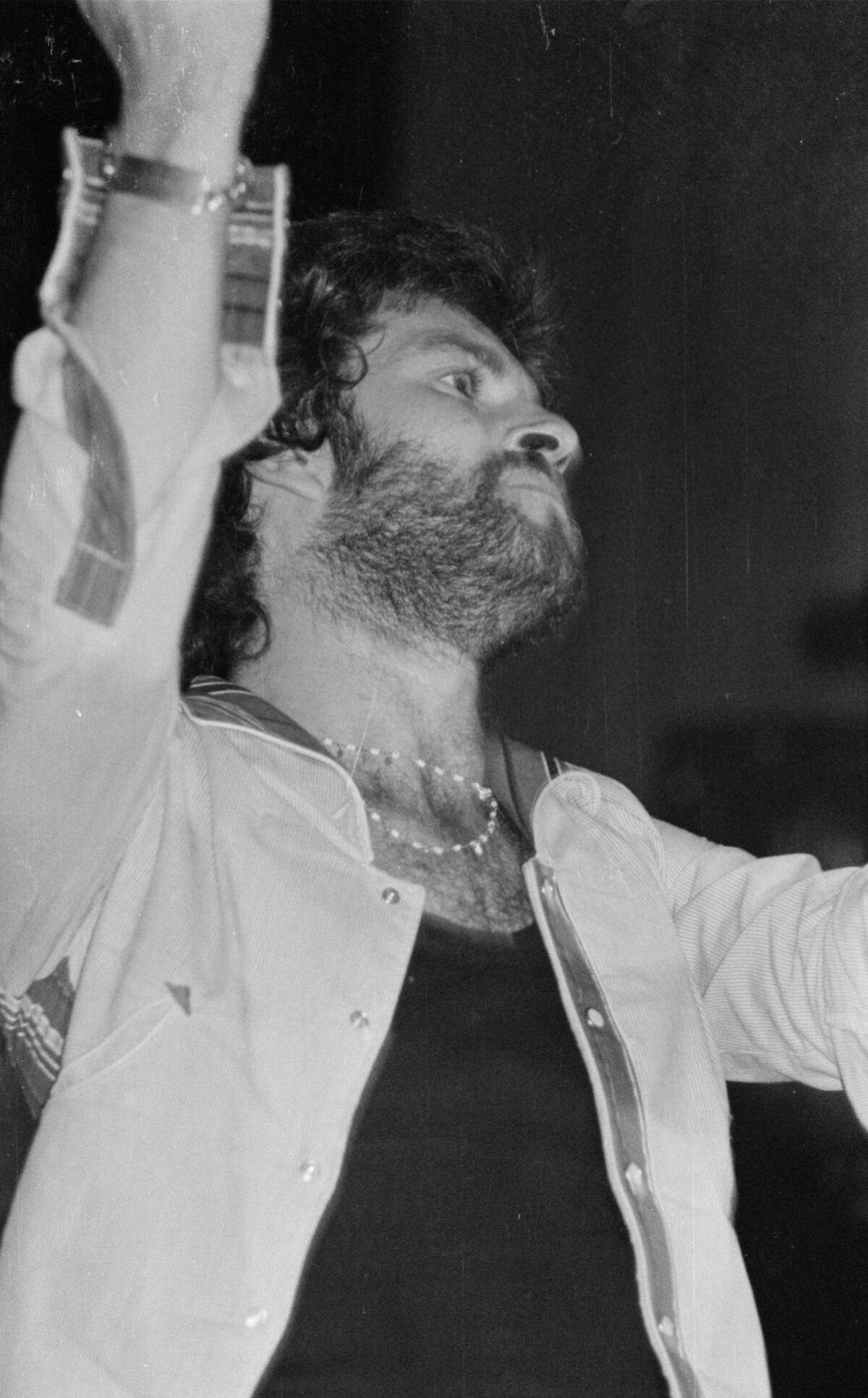

We found Ticker by advertising in the newspaper. He had trouble staying on pitch, but he was very charismatic and just a delightful human being.

We all (except Ticker) lived in and around Burton upon Trent, which had a very lively live music scene, meaning we often encountered one another at gigs. Sped’s dad was a builder and property developer who owned a square of lock-up garages. He let us have the use of the first one on the right, which was large, and we “soundproofed” it (to a degree). This is where we would gather to practise.

The songs were already fully formed and arranged in my head, so I could play the bass part to Dave Kent, give Sped an idea of what I wanted in the lead breaks, do some mouth drumming (I might have accidentally invented beatboxing) to Graham to convey the important bits, and let Nala go off-piste with the sax.

Regarding the name Cargo, actually, that came second. I remember describing our first renditions of some of the songs and telling anyone who asked how proud I was of the way the boys had responded (I was horribly intense back then and somewhat dictatorial), saying that we were really “delivering the goods.” The name kind of suggested itself!

We had no idea that there was a Dutch band called Cargo because, as you may know, there was no internet, no Wi-Fi, no cellphones, nobody had laptops (or desktops), and there were only three TV channels.

Let’s talk gear: what can you recall about the amps, instruments, and the entire setup you had?

I don’t ever remember gear being an issue. I had a Marshall head and Laney stack and several guitars. Sped had his own gear…an Orange head and HiWatt cabinet…and a couple of Gibson SGs. Graham obviously had his drums already (he was playing with dance bands for a living). Dave must have had a bass rig.

For the life of me, I cannot remember if we had our own PA. I guess we must have. However, the large venues all had their own in-house PA systems; the Roundhouse, Finsbury Rainbow, the Marquee, etc.

Did Cargo play a lot of gigs during your brief run? What were the most memorable venues you played?

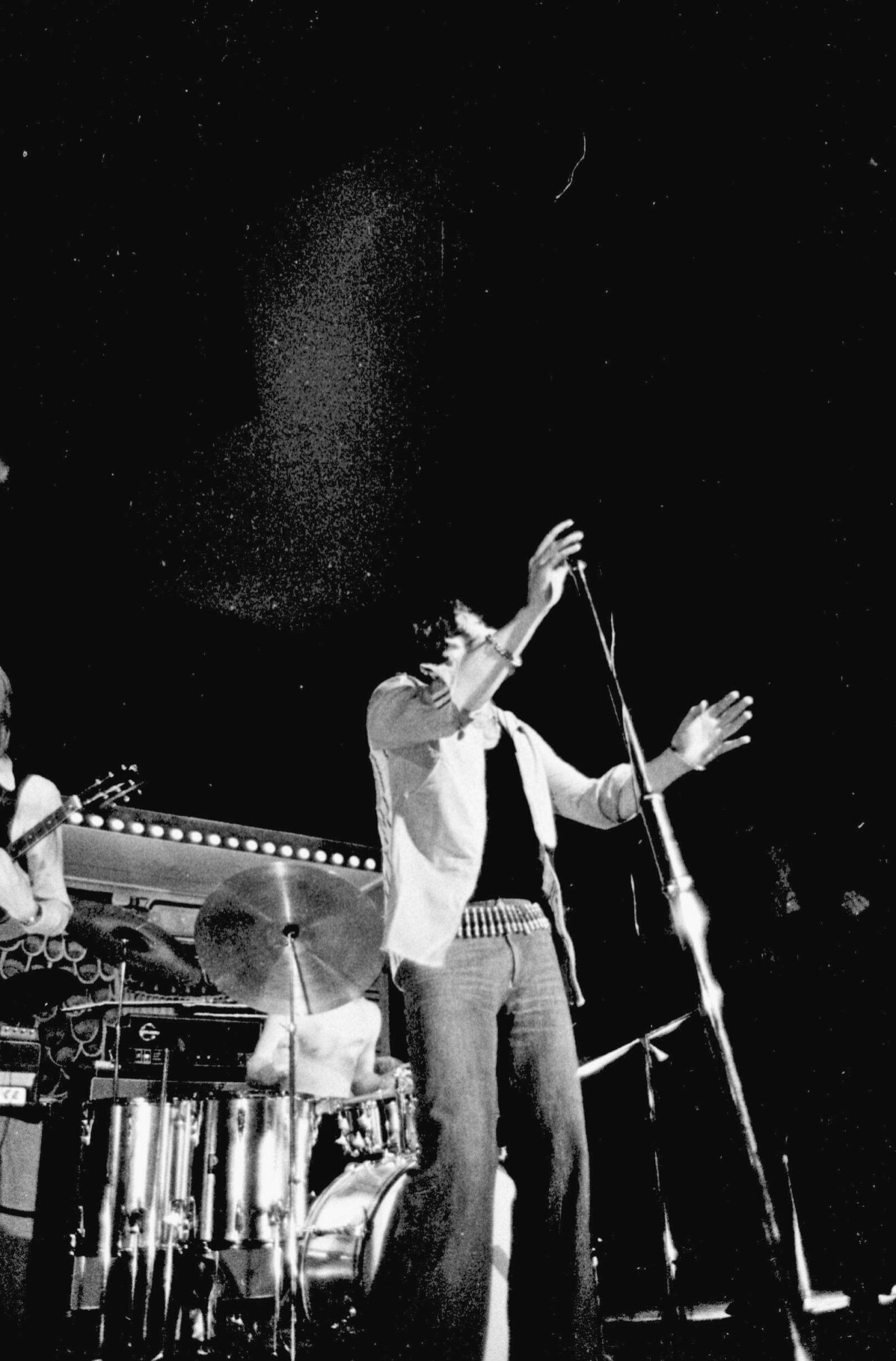

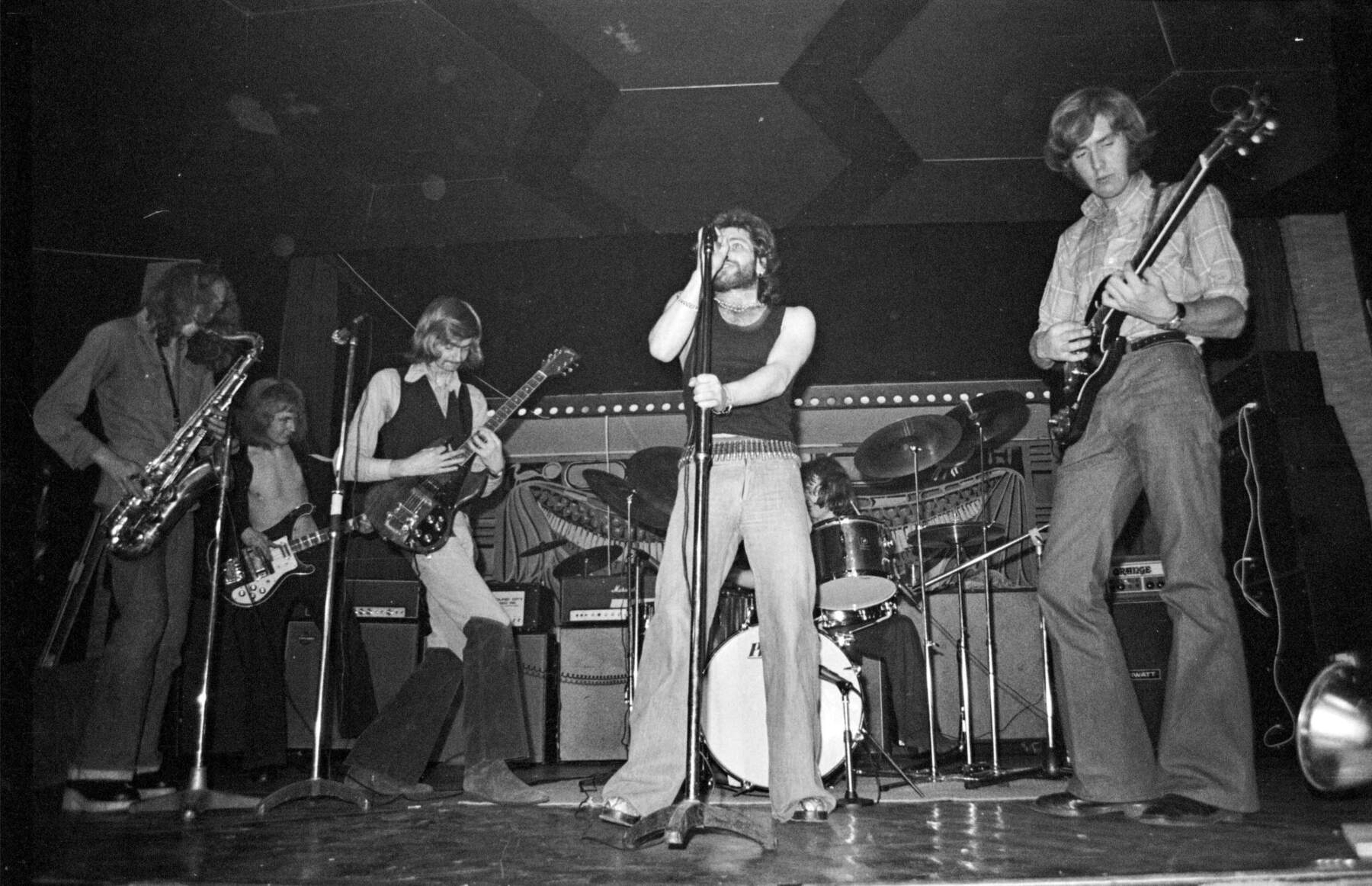

Yes, we played a lot. We had an agent to get us gigs. The ones we remember supporting were Greenslade, East of Eden, Sam Apple Pie, Stray, and most notably, of course, Queen. There were also many gigs where we headlined. The photos in the sleeve notes were all taken at Cleopatra’s, a nightclub in Derby.

What’s the craziest or most vivid anecdote you can recall from Cargo gigs?

Oh, the Queen gig for sure. It was Peterborough Town Hall. They were just about to become huge, but we hadn’t heard of them before. Freddie was a skinny little thing in his leather, studded catsuit.

Anyhow, they wanted to get off early to get back to London, so they asked us if they could go on before us. Sped thinks it was because the last bus left at 10:00, but I don’t remember it that way. Anyhow, we agreed.

That is why I claimed (humorously) for many years afterward that Queen had supported us.

Tell us about the recordings Guerssen issued and how they originally got in touch with you.

So a fellow called Austin Matthews called me out of the blue one day. I’m normally very suspicious of unsolicited phone calls, so I don’t know why I took it, and he said, “Are you anything to do with a band called Cargo? I’ve heard your music on the internet and I really like it.” Well, you could have knocked me down with a feather.

It’s a very long story, but suffice it to say that on the day of the recording, Doris was out of action, so a good friend, Ken McPherson, borrowed one of his dad’s vans and drove us to Zella. It turns out that he must have asked for an acetate, but we didn’t know that.

Anyhow, Ken went on to found his own studio, called The Track Station, under the railway arches in Burton (yes, I know, right?). He must have uploaded his copy to a very obscure website called The British Music Archive. Somehow Austin found it, and thus found us. He was determined to get the demo published and introduced us to Alex at Guerssen. The rest, as they say, is history.

We understand these sessions took place in 1973, where you recorded a demo acetate titled ‘Delivering The Goods’ at Zella Studios. What are some of your strongest memories from the recordings?

Strongest memories of the recording? Well, we paid for this ourselves, so we could only afford three hours. The first hour was spent setting everything up… Graham in the glass booth, us lined along the right-hand wall as Graham saw us. It was a long, narrow room, with the guys from Zella setting levels and so on.

We realised by then that we would only have time to play each song once. It is, effectively, a “live” album, and that’s what we did. We couldn’t see each other properly, which is why there are mistakes on the recording. If it had been a proper recording session, we would have re-recorded those, but there was no time. On stage, you can see each other, and many of the changes were signalled by me nodding my head. We were very tight live.

Anyhow, Ticker went into the vocal isolation booth and laid down the vocals, improvising many of the lyrics because he had yet to memorise them!! Upon playback, it was obvious to us all that it was “pitchy,” but there was no time to do them again, so he double-tracked a few bits. It didn’t improve matters.

Once those master tapes were in your hands, what was the first thing you did with the recordings? Did you send the music out to any labels or radio stations? You almost signed with Island?

We never had the master tapes, Klemen. They don’t belong to you; they belong to the studio. Two-inch tape was expensive, and they would almost certainly have reused it for the next client who walked in the door.

We each had one acetate (plus Ken, as it turns out), but luckily Graham asked for a cassette. I still have my acetate (picture attached), but it is worn out and unplayable. The recordings that Guerssen used, and with which they have done such a good job, were salvaged from the 50-year-old cassette by me and my younger son at his studio in Seahouses, Northumberland. My son is a founder member of the hugely acclaimed band Leisure Society.

Anyhow, with my acetate in my hand, I started telephoning all the labels I could find in the Yellow Pages. It was soul-destroying work. Finally, I got through to Island and asked for Muff Winwood, more in hope than expectation. To my amazement, he picked up, and we had a brief chat and fixed an appointment.

On the appointed day, Graham and I got into my old Zephyr 6 and drove down to London. In those days, there was virtually no traffic on the M1; you could drive right down Maida Vale and into Soho and park in Golden Square, which is what we did.

Mr Winwood was very gracious and gave the acetate a listen. He came back to us and told us that he wouldn’t be taking matters any further, but he would be interested in signing the drummer and the singer.

Being young, inexperienced, and foolish, we declined and told him it was all or nothing. So it was nothing.

Looking back at the quality of the tracks and the overall sound, many listeners find it baffling that you weren’t signed. Why do you think the breakthrough eluded you?

As you might imagine, Klemen, I tend to only hear the mistakes. It was very tempting to do all sorts of digital wizardry with the files using my DAW, to isolate the vocal and “tune” it, to edit out the false starts and overruns. However, sanity prevailed, and we left them exactly how they were recorded, faults and all.

What comes across, IMHO, is the vitality, the energy, the excitement, the virtuosity. Graham’s work is outstanding, as I’m sure you noticed, and so was Sped’s. Of course, I am very proud of the compositions and still play them on my guitar at home for my own amusement.

I know this was a very long time ago, but hearing those tracks again, are there one or two songs whose story you can directly address?

Oh yes indeed. Regrettably, most of the songs allude to goings-on that would get me cancelled or possibly arrested nowadays!!

‘Margate 73,’ however, is about our first-ever gig. We were on the bill with Rotgut (I think) at the Dreamland Ballroom.

My “opus,” ‘Elements,’ is a rhapsody. It represents Earth, Wind, Fire, and Water, and it is my favourite composition.

‘Spaced Out Maurice’ is about those office types who trudge to work all week and then go mental at the weekend, doing drugs and headbanging to live rock bands. We despised them (even though they were paying our wages!!) because we were so dedicated and starving for our “art”. At least, that’s how we saw it.

Who were your main influences when it came to your instrument? And when it comes to the band’s overall sound, what collective influences were you drawing from?

My first musical awakenings began when I was five. I remember that my mother would have the radio on most of the day, and I heard recordings by the Big Ben Banjo Band. I had no idea what a banjo was (nor any other musical instruments, actually), but the sound entranced me. My destiny was sealed. I wanted to make such joyous sounds.

When did you disband? What ultimately led to the breakup? Was the lack of interest from labels the main, definitive cause?

You are very astute. Yes, the lack of interest really knocked us back. We knew the demo was flawed, but honestly thought that they would hear the virtuosity, the creativity, and the originality. Sadly, that didn’t happen, so we never had the chance to get back into a label-funded studio and do the songs justice.

Once the band ended, what followed for you and the other members? Was anyone involved in the music industry later on, or did life take you down entirely different paths?

I have never stopped playing, although once I married and had children it was necessary to get a “proper” job and buy a house, etc. I took early retirement in 2009 and immediately went back to it.

I was living in Marin County, California at the time, and I joined a “Swampy Tonk” band called Miracle Mule. I also made a very good living touring senior living communities all over Northern California as a “crooner,” revisiting the golden age of the Big Band era and the timeless songs of the Rat Pack. There are tons of videos on my website.

Sped still plays with his band JM2 (although it is more like JM27 by now.

What currently occupies your life these days?

I am very happily retired, thank you, Klemen. I only stopped gigging in May of this year. I am currently exploring the creative possibilities of AI and starting to make artistic music videos of my own compositions. It is proving tricky, as the AI can produce unexpected results and you have to word your prompts very carefully. I’m learning, however.

Thank you so much for your time and for sharing these memories. My final question: how does it feel that these recordings are now available, and that a new, younger generation of people can hear the music of Cargo?

It is amazing. I cannot thank Austin enough for his determination to make this happen, and Guerssen for their incredible work. I have the album framed on my wall. The fact that it is available on so many streaming platforms is, frankly, stunning.

Thank you once again for your interest, Klemen.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Cargo (On stage at Cleopatra’s. A nightclub and live music venue in Derby in 1973) (“We used to go there to see all the visiting American acts that used to tour extensively back in the day. Unlike todays stadium tours where you need to take out a second mortgage in order to buy a ticket, back then you could pay on the door AND be able to afford a pint or two. I’ll never forget on one occasion Sped, Graham and I went to see a fabulous Motown act there and the police raided the joint looking for drugs. The senior detective in charge took to the stage and sardonically told us “You came to see The Showstoppers – well, you’ve seen us. Now fuck off!”.)

Andrew Clyde Website

Guerssen Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / X / Bandcamp / YouTube