Quintessentially a cosmic trip

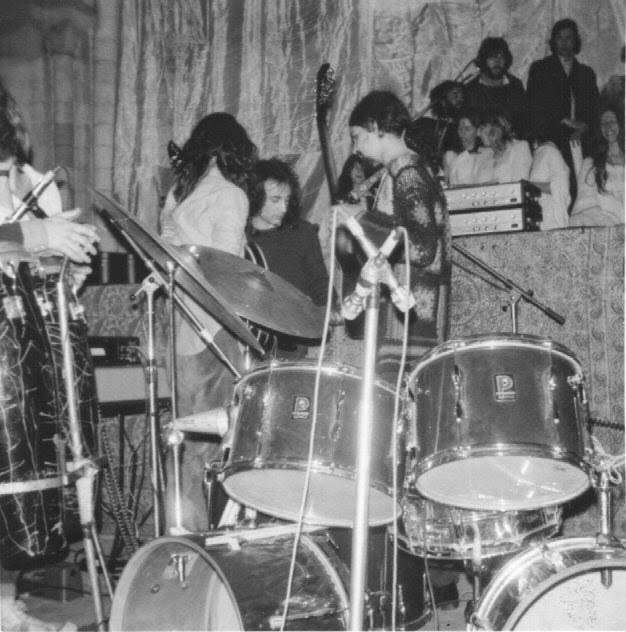

Quintessence © Colin Lourie

Featuring a new

interview with Phil Shiva Jones of Quintessence and

interview with Phil Shiva Jones of Quintessence and

Australian 60s legends The Unknown Blues

© Dave Codling

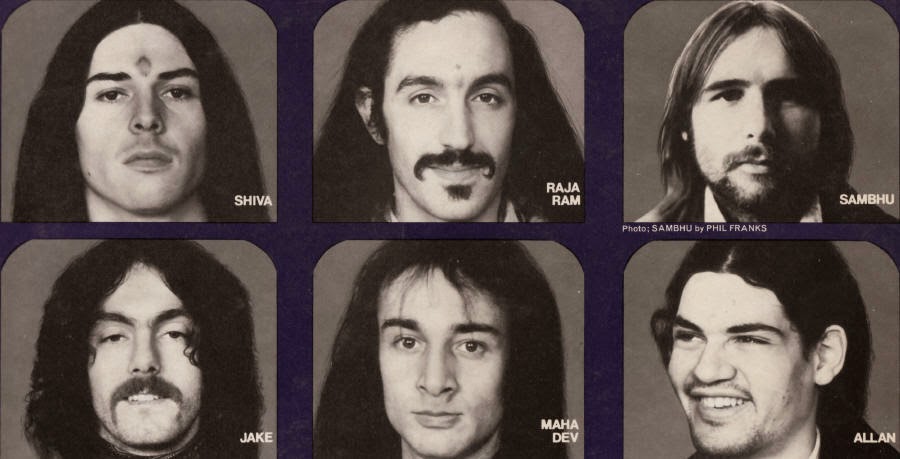

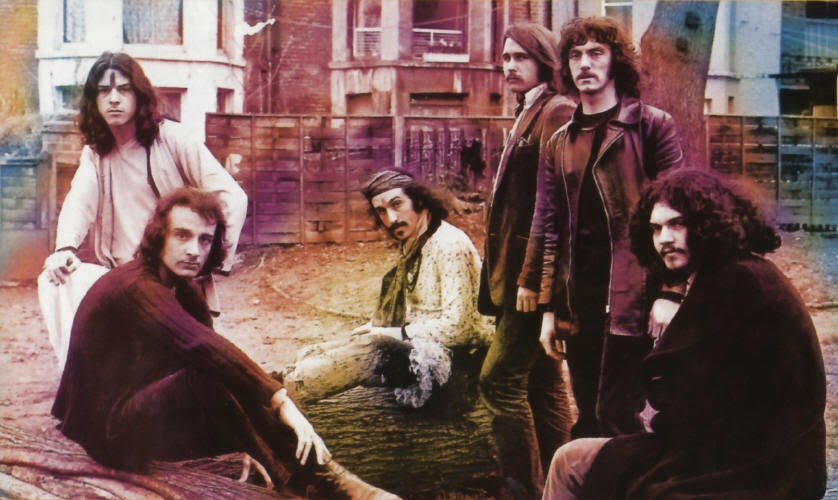

In one street in the bohemian centre of probably the most

cosmopolitan city of the day, six musicians of five nationalities formed a band

dedicated to the celebration of spirituality in music. Only two knew each other

before, yet within weeks the most important label’s owner visited their

rehearsal under a fish and chip shop and signed a three-album contract with

music and cover freedom, culminating in selling out the Royal Albert Hall

twice. The period is as easy to guess as the scenario is hard to believe. The

story, however, isn’t just a band history—without precursors—but more a way of

life reflecting a new era of awareness which endures into the present day.

cosmopolitan city of the day, six musicians of five nationalities formed a band

dedicated to the celebration of spirituality in music. Only two knew each other

before, yet within weeks the most important label’s owner visited their

rehearsal under a fish and chip shop and signed a three-album contract with

music and cover freedom, culminating in selling out the Royal Albert Hall

twice. The period is as easy to guess as the scenario is hard to believe. The

story, however, isn’t just a band history—without precursors—but more a way of

life reflecting a new era of awareness which endures into the present day.

The ’60s hit

America when close to half of the citizens were under 25 years-old, so a sea-change

was probably inevitable there. It soon blossomed abroad as musicians gathered

to forge their own style and vision. Ron ‘Raja Ram’ Rothfield, born in

Melbourne to Jewish parents, first learned the violin but changed to flute when

in Ibiza in ’61, taking a music degree in it before moving to New York four

years later. There he studied jazz with Lennie Tristano at a dollar a minute,

“which was worth it”, and performed with American guitarist/bassist Richard

‘Shambhu Baba’ Vaughan. In April 1969 they settled in London’s Ladbroke Grove

and advertised for musicians with the proviso that they must also live in W10.

America when close to half of the citizens were under 25 years-old, so a sea-change

was probably inevitable there. It soon blossomed abroad as musicians gathered

to forge their own style and vision. Ron ‘Raja Ram’ Rothfield, born in

Melbourne to Jewish parents, first learned the violin but changed to flute when

in Ibiza in ’61, taking a music degree in it before moving to New York four

years later. There he studied jazz with Lennie Tristano at a dollar a minute,

“which was worth it”, and performed with American guitarist/bassist Richard

‘Shambhu Baba’ Vaughan. In April 1969 they settled in London’s Ladbroke Grove

and advertised for musicians with the proviso that they must also live in W10.

A couple of

streets away lived Phil Jones, who as a child sang what he later discovered

were African-American spirituals as if from a previous life. First touring in a

boys’ choir he became a teenage star in his native Sydney fronting the Unknown

Blues on vocals and mouth harp. The school quintet soon got a debut hit single

and national press praising their authenticity as Australia’s first blues-rock

band. After five singles the soon-to-be-christened Shiva Shankar literally

dreamed of finding a master in England, the land of his ancestors (his father

had Welsh origins, mother from Irish and French). In 1968 he paid his way there

as a singer on a cruise-ship then worked in a picture-frame factory when he saw

a Melody Maker ad for a singer. When first meeting the house guru he was

greeted with “Good to see you again”.

streets away lived Phil Jones, who as a child sang what he later discovered

were African-American spirituals as if from a previous life. First touring in a

boys’ choir he became a teenage star in his native Sydney fronting the Unknown

Blues on vocals and mouth harp. The school quintet soon got a debut hit single

and national press praising their authenticity as Australia’s first blues-rock

band. After five singles the soon-to-be-christened Shiva Shankar literally

dreamed of finding a master in England, the land of his ancestors (his father

had Welsh origins, mother from Irish and French). In 1968 he paid his way there

as a singer on a cruise-ship then worked in a picture-frame factory when he saw

a Melody Maker ad for a singer. When first meeting the house guru he was

greeted with “Good to see you again”.

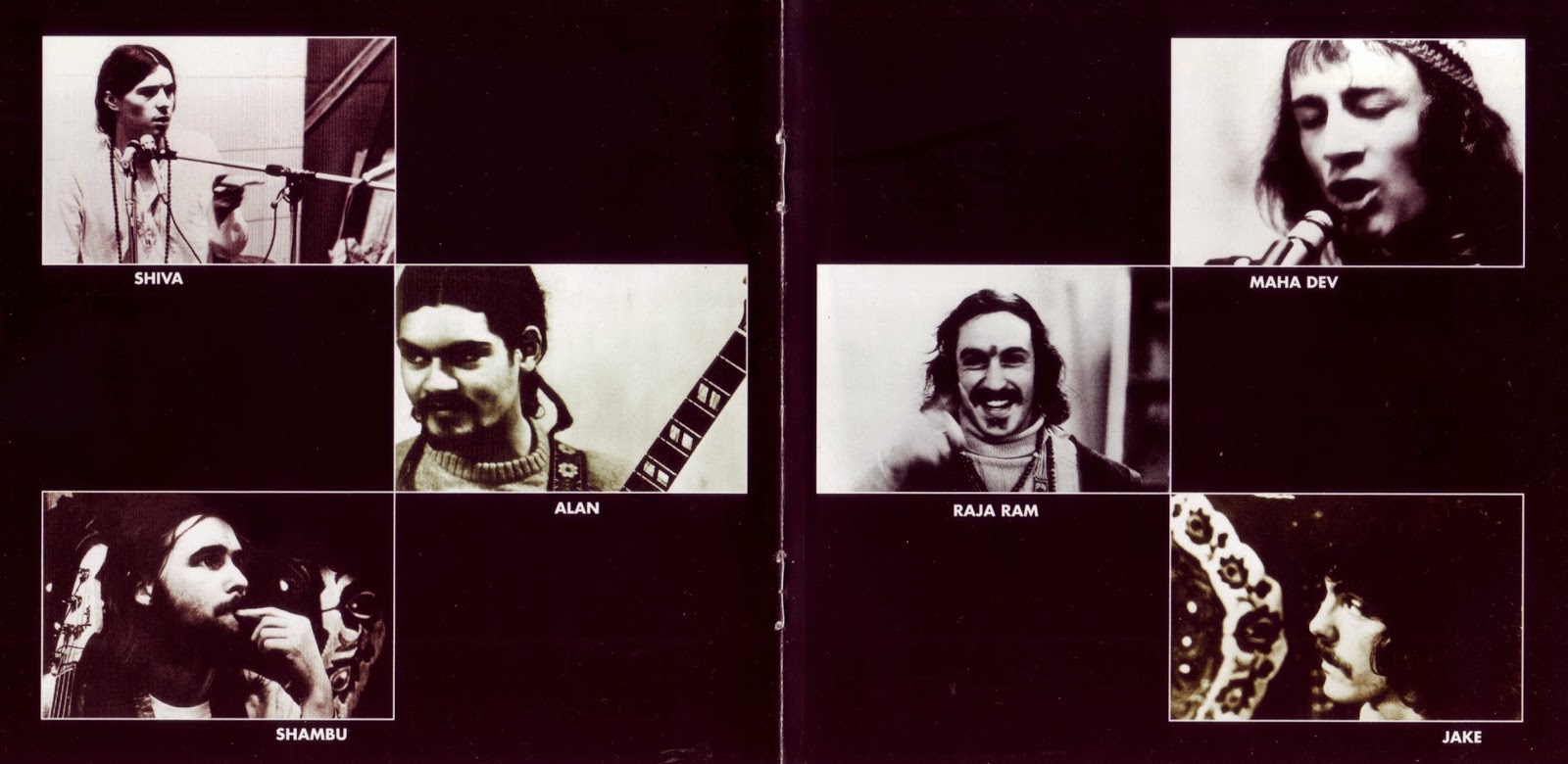

Two hundred

replies further resulted in the enrolment of the 16 year-old Allan Mostert

(lead guitar; sitar) from Mauritius, Maha Dev (Dave Codling rhythm guitar) from

Leeds—who gave up his art teaching job in St. Albans —and a Canadian Jake

Milton (drums), said to have been in Junior’s Eyes though eludes their

histories; he lived in Shepherd’s Bush but promised to move. Their Oxford

Gardens house soon became a meeting-place for 30-40 musicians, poets including

Stanley Barr who wrote lyrics and became their manager, artists like Gopala

(Maha Dev’s brother-in-law) who lived in the same street and later designed

their albums, and a guru who had a life-long influence: Swami Ambikananda

(1934-1997). This clairvoyant spiritual teacher guided them in a

non-denominational universal faith, though each was on their own path. He

bestowed spiritual names based on individual characteristics: Shiva was the

patron God of yoga and the arts who lived an ascetic life on Mount Kailash, and

both Maha Dev (Maha-great, deva-god) and Shambu were associative names for

Shiva.

replies further resulted in the enrolment of the 16 year-old Allan Mostert

(lead guitar; sitar) from Mauritius, Maha Dev (Dave Codling rhythm guitar) from

Leeds—who gave up his art teaching job in St. Albans —and a Canadian Jake

Milton (drums), said to have been in Junior’s Eyes though eludes their

histories; he lived in Shepherd’s Bush but promised to move. Their Oxford

Gardens house soon became a meeting-place for 30-40 musicians, poets including

Stanley Barr who wrote lyrics and became their manager, artists like Gopala

(Maha Dev’s brother-in-law) who lived in the same street and later designed

their albums, and a guru who had a life-long influence: Swami Ambikananda

(1934-1997). This clairvoyant spiritual teacher guided them in a

non-denominational universal faith, though each was on their own path. He

bestowed spiritual names based on individual characteristics: Shiva was the

patron God of yoga and the arts who lived an ascetic life on Mount Kailash, and

both Maha Dev (Maha-great, deva-god) and Shambu were associative names for

Shiva.

Shiva and Swami

It was a vibrant,

less self-conscious version of Greenwich Village at the heart of England’s

counterculture where lived Hawkwind, Pink Fairies, Skin Alley, Cochise, Quiver,

Steamhammer, Third Ear Band, and Tyrannosaurus Rex among others (Shiva

sometimes wondered why Bolan never said good morning). Round the corner Mighty

Baby’s commune embraced Sufism. The underground scene was the labour ward for

nascent progressive music as we know it today. Quintessence (“the fifth

substance, apart but derived from the four elements composing the heavenly

bodies, latent in all things”) played their first gig (like Hawkwind Zoo) at

All Saints Church off Portobello Road thanks to the friendly vicar, where 400

souls crammed in due to word of mouth. A show at the Camden Arts Lab was

filmed. Songs destined for the first album were premiered: Giants, Pearl And

Bird, Ganga Mai plus the odd Doors track. In June they first appeared on

posters (as Shiva and the Quintessence) for Implosion at Camden’s former

locomotive depot the Roundhouse, another area embedded in their history.

Several early gigs were benefits, for example in aid of Release which helped

people on drug charges, and hippydom’s International Times who interviewed them

in August ’69. This communal band never forgot these roots.

less self-conscious version of Greenwich Village at the heart of England’s

counterculture where lived Hawkwind, Pink Fairies, Skin Alley, Cochise, Quiver,

Steamhammer, Third Ear Band, and Tyrannosaurus Rex among others (Shiva

sometimes wondered why Bolan never said good morning). Round the corner Mighty

Baby’s commune embraced Sufism. The underground scene was the labour ward for

nascent progressive music as we know it today. Quintessence (“the fifth

substance, apart but derived from the four elements composing the heavenly

bodies, latent in all things”) played their first gig (like Hawkwind Zoo) at

All Saints Church off Portobello Road thanks to the friendly vicar, where 400

souls crammed in due to word of mouth. A show at the Camden Arts Lab was

filmed. Songs destined for the first album were premiered: Giants, Pearl And

Bird, Ganga Mai plus the odd Doors track. In June they first appeared on

posters (as Shiva and the Quintessence) for Implosion at Camden’s former

locomotive depot the Roundhouse, another area embedded in their history.

Several early gigs were benefits, for example in aid of Release which helped

people on drug charges, and hippydom’s International Times who interviewed them

in August ’69. This communal band never forgot these roots.

The Quintessence

sound immediately fused elements from psych-rock, jazz and blues to Indian raga

in true progressive style. New Age before coined, it was extended just as the

oft-cited Indian connection was but one influence with Japan, Tibet and western

music in a free-form collage. The plan was to replicate the sound in listeners’

heads, they said, a mesmerising intoxication not as a projection but

identification with the audience seen as participators in the experience, to

which each musician contributed and shared ideas. Their many early interviews

(Zig Zag, The Times, Time Out etc) focused on this—with the ethos of the Grove

from where it stemmed—which they called a mind and body dance, a physical and

mental (spiritual) celebration. Never overserious but a joyful buzz whereby

time structures and chord modulations frequently shift around a central riff, a

spiritual Can that “ebbs and flows, coils, surges and ripples, occasionally

with infinite beauty” wrote a reviewer at the time. The wave was certainly fast

moving.

sound immediately fused elements from psych-rock, jazz and blues to Indian raga

in true progressive style. New Age before coined, it was extended just as the

oft-cited Indian connection was but one influence with Japan, Tibet and western

music in a free-form collage. The plan was to replicate the sound in listeners’

heads, they said, a mesmerising intoxication not as a projection but

identification with the audience seen as participators in the experience, to

which each musician contributed and shared ideas. Their many early interviews

(Zig Zag, The Times, Time Out etc) focused on this—with the ethos of the Grove

from where it stemmed—which they called a mind and body dance, a physical and

mental (spiritual) celebration. Never overserious but a joyful buzz whereby

time structures and chord modulations frequently shift around a central riff, a

spiritual Can that “ebbs and flows, coils, surges and ripples, occasionally

with infinite beauty” wrote a reviewer at the time. The wave was certainly fast

moving.

While rehearsing

under a fish and chip shop, word reached Island’s Chris Blackwell and Muff

Winwood who came to listen. Perhaps they’d seen Raja Ram’s illustrated

interview in Time Out when still a counterculture mag. It was July, sixteen

weeks into the band’s career: a contract was offered on the spot. When

Warners-Reprise—among at least six dorsal-finned labels—also dined the band in

veggie restaurants, Island immediately doubled their offer. Fortunately—Reprise

was responsible for some great talents leaving the music biz such as Nick

Pickett—Quintessence considered Island the place to be, incredibly offering the

new act unlimited freedom. The leading NEMS agency soon signed them for the

Roundhouse (again), prestigious Speakeasy, Reading Uni with Pink Floyd, and a

high-profile free concert at Hyde Park with Soft Machine, Deviants, Edgar

Broughton, and Al Stewart, filmed by Jack Moore of the London Arts Lab

collective. It was rumoured Jefferson Airplane were lined-up but couldn’t get

work visas. Quintessence entered the studio in August during the heady summer

of ’69.

under a fish and chip shop, word reached Island’s Chris Blackwell and Muff

Winwood who came to listen. Perhaps they’d seen Raja Ram’s illustrated

interview in Time Out when still a counterculture mag. It was July, sixteen

weeks into the band’s career: a contract was offered on the spot. When

Warners-Reprise—among at least six dorsal-finned labels—also dined the band in

veggie restaurants, Island immediately doubled their offer. Fortunately—Reprise

was responsible for some great talents leaving the music biz such as Nick

Pickett—Quintessence considered Island the place to be, incredibly offering the

new act unlimited freedom. The leading NEMS agency soon signed them for the

Roundhouse (again), prestigious Speakeasy, Reading Uni with Pink Floyd, and a

high-profile free concert at Hyde Park with Soft Machine, Deviants, Edgar

Broughton, and Al Stewart, filmed by Jack Moore of the London Arts Lab

collective. It was rumoured Jefferson Airplane were lined-up but couldn’t get

work visas. Quintessence entered the studio in August during the heady summer

of ’69.

Quintessence © Colin Lourie

That November saw

In Blissful Company, a seven-tracker featuring early progressive instrumentals

like Midnight Mode’s slowed-down recording of a tamboura. Two months later a

debut single Notting Hill Gate c/w Move Into The Light opens with a clear statement

(someone dragging on a joint) for a faster more fuzz-laden manifesto than the

LP track, like the album’s opener Giants recalling the mythic race in

Anglo-Saxon chronicles influential on Tolkien.

In Blissful Company, a seven-tracker featuring early progressive instrumentals

like Midnight Mode’s slowed-down recording of a tamboura. Two months later a

debut single Notting Hill Gate c/w Move Into The Light opens with a clear statement

(someone dragging on a joint) for a faster more fuzz-laden manifesto than the

LP track, like the album’s opener Giants recalling the mythic race in

Anglo-Saxon chronicles influential on Tolkien.

Ganga Mai soon appeared on the

first Island sampler. Setting their stall out early, the songs stayed integral

(but never the same) throughout their career. The inner sleeve shows the

in-house ashram under an ancient tree; their poet-manager stands seventh from

the left and the Swami smiles with Shiva. With a glued-in booklet, the first

copies had a 50 x 65cm colour poster of Krishna for what was Island’s most

expensive cover production.

first Island sampler. Setting their stall out early, the songs stayed integral

(but never the same) throughout their career. The inner sleeve shows the

in-house ashram under an ancient tree; their poet-manager stands seventh from

the left and the Swami smiles with Shiva. With a glued-in booklet, the first

copies had a 50 x 65cm colour poster of Krishna for what was Island’s most

expensive cover production.

An interviewer

learned that making music is a spiritual experience, like holy work, described

even then as “trance music” decades before the genre appeared. “Our music’s

highly improvised and celestial…for example Indian instruments have an amazing

subtlety, really on subtle planes”. A concert is not only a giving out but also

receiving of energy, a circle is created like feeling completely charged after

a switch turns. Euphoric crescendos in a kaleidoscope of sound melt to leave

space for reflection, before building up again with another instrument for

melodic and dynamic variety in a rare rapport that they sought to transfer to

the colder platform of vinyl. It’s not hyperbole to say that the joyous

intensity, on good days, produced something close to rapture for audiences.

This exaltation is often described by John McLaughlin as “an entering of

spirit” which led to his Mahavishnu Orchestra. Communication (“A lot of

bullshit is said about the difficulties of communication, but Van Gogh had it

harder than any of us have it today”) reaches a point where there ceases to be

an audience and a performer wrote Bob Partridge (Time Out Nov. 1969), “a state

of being such that the people are the body and the band are the voice of that

body. It becomes a celebration. For this reason I believe that sooner or later

they must emerge as one of the truly great groups of our time”. Within two years

Quintessence was being called the greatest live act on the planet.

learned that making music is a spiritual experience, like holy work, described

even then as “trance music” decades before the genre appeared. “Our music’s

highly improvised and celestial…for example Indian instruments have an amazing

subtlety, really on subtle planes”. A concert is not only a giving out but also

receiving of energy, a circle is created like feeling completely charged after

a switch turns. Euphoric crescendos in a kaleidoscope of sound melt to leave

space for reflection, before building up again with another instrument for

melodic and dynamic variety in a rare rapport that they sought to transfer to

the colder platform of vinyl. It’s not hyperbole to say that the joyous

intensity, on good days, produced something close to rapture for audiences.

This exaltation is often described by John McLaughlin as “an entering of

spirit” which led to his Mahavishnu Orchestra. Communication (“A lot of

bullshit is said about the difficulties of communication, but Van Gogh had it

harder than any of us have it today”) reaches a point where there ceases to be

an audience and a performer wrote Bob Partridge (Time Out Nov. 1969), “a state

of being such that the people are the body and the band are the voice of that

body. It becomes a celebration. For this reason I believe that sooner or later

they must emerge as one of the truly great groups of our time”. Within two years

Quintessence was being called the greatest live act on the planet.

That month they

debuted at St. Pancras (Camden) Town Hall, an important venue in their career,

in aid of the underground paper Gandalf’s Garden. Their furthest-to-date gig

was at Sunderland’s Locarno supporting Free (returning to headline there two

months later), then London University for what must have been the last days of

psych with Eire Apparent and Octopus. At Hammersmith Town Hall they played with

the Radha Krishna Temple riding high on their George Harrison-produced

hits. Many associate them with

Quintessence but in fact the relationship wasn’t exactly harmonious. Krishna

Consciousness devotees warned fans that they were being led away from

spirituality, and would button-hole the musicians backstage to try and claim

them for their own. This fundamentalist approach was shared by the Jesus

freaks, but the band said they weren’t evangelists, everyone finds their own

path, unified but different too for each band member. “God is God, whatever

name is used, a universal concept”.

debuted at St. Pancras (Camden) Town Hall, an important venue in their career,

in aid of the underground paper Gandalf’s Garden. Their furthest-to-date gig

was at Sunderland’s Locarno supporting Free (returning to headline there two

months later), then London University for what must have been the last days of

psych with Eire Apparent and Octopus. At Hammersmith Town Hall they played with

the Radha Krishna Temple riding high on their George Harrison-produced

hits. Many associate them with

Quintessence but in fact the relationship wasn’t exactly harmonious. Krishna

Consciousness devotees warned fans that they were being led away from

spirituality, and would button-hole the musicians backstage to try and claim

them for their own. This fundamentalist approach was shared by the Jesus

freaks, but the band said they weren’t evangelists, everyone finds their own

path, unified but different too for each band member. “God is God, whatever

name is used, a universal concept”.

Swami Ambikananda,

who occasionally attended rehearsals and concerts, taught that Krishna and the

Hindu pantheon, Christ—as a pre-Church prophet of love and wonderment—Moses,

Buddha and other apostles were on the same journey of spiritual enlightenment.

The band’s deep respect endures today, Shiva in 2005 describing him as a

constant shining spiritual sun, a master of spiritual psychology able to create

a mirror effect for one’s self, the good and the bad. Allan Mostert recalls

that it was a high just to be in his presence, and remains the most important

experience in his life. Swami-ji, as he was known, didn’t conform to any

stereotype: he recommended that the group stop smoking, except Maha Dev, “he must

smoke!” The guitarist’s father had been a fireman in the war and believed that

the son had been a pilot killed in a plane fire before this incarnation. When

he smoked in the tour van they all crowded round him!

who occasionally attended rehearsals and concerts, taught that Krishna and the

Hindu pantheon, Christ—as a pre-Church prophet of love and wonderment—Moses,

Buddha and other apostles were on the same journey of spiritual enlightenment.

The band’s deep respect endures today, Shiva in 2005 describing him as a

constant shining spiritual sun, a master of spiritual psychology able to create

a mirror effect for one’s self, the good and the bad. Allan Mostert recalls

that it was a high just to be in his presence, and remains the most important

experience in his life. Swami-ji, as he was known, didn’t conform to any

stereotype: he recommended that the group stop smoking, except Maha Dev, “he must

smoke!” The guitarist’s father had been a fireman in the war and believed that

the son had been a pilot killed in a plane fire before this incarnation. When

he smoked in the tour van they all crowded round him!

In March 1970

Quintessence returned to St. Pancras Hall to record live for Island, a standard

policy of the label then, also filmed by Solus Productions who were friends

with Jake Milton. BBC 2 expressed interest in a cinema release of the footage.

In spite of the band rarely touring on a daily basis—they preferred time to

write, practice, meditate and explore other art forms—their rise was still

meteoric. Exactly one year after the band-forming ad they supported Creedence

Clearwater Revival for two nights at the Royal Albert Hall, also filmed by the

BBC. Two weeks later they were invited to play at Montreux, to be aired on

Swiss TV; a London show that month may have been filmed by Dutch and German TV.

The Montreux programme enthused about “one of the best new bands in Europe

today. Individually they sparkle. Collectively they shine…When the year has

ended Quintessence will be one of the biggest bands in the world”—not bad for a

European debut.

Quintessence returned to St. Pancras Hall to record live for Island, a standard

policy of the label then, also filmed by Solus Productions who were friends

with Jake Milton. BBC 2 expressed interest in a cinema release of the footage.

In spite of the band rarely touring on a daily basis—they preferred time to

write, practice, meditate and explore other art forms—their rise was still

meteoric. Exactly one year after the band-forming ad they supported Creedence

Clearwater Revival for two nights at the Royal Albert Hall, also filmed by the

BBC. Two weeks later they were invited to play at Montreux, to be aired on

Swiss TV; a London show that month may have been filmed by Dutch and German TV.

The Montreux programme enthused about “one of the best new bands in Europe

today. Individually they sparkle. Collectively they shine…When the year has

ended Quintessence will be one of the biggest bands in the world”—not bad for a

European debut.

Early that summer

they appeared on successive days at two of the greatest festivals, at Bath (with

Fleetwood Mac, Soft Machine etc) and second-billing to Traffic on the final day

at the Hollywood (Midlands) Festival that had one of the most stellar bills

ever witnessed. This was filmed by Solus for an unfinished Beeb documentary,

though they broadcast them at the ubiquitous St.Pancras Hall for BBC2’s Disco

Two: Sounds On Saturday. Down the road at the Lyceum a new record attendance

was established. Though audiences

wouldn’t notice, festivals created a tricky problem to overcome. At Hollywood

they had to follow Black Sabbath, which Allan recalls was near-catastrophic

because the negative vibes didn’t help getting into their own mood. Due to come

on after Deep Purple—probably at Aachen in 1970—the Black (K)nighters went well

over time against etiquette, then Blackmore poured petrol on the stacks

requiring the fire brigade and police. Quintessence played 20 minutes before

the authorities cut the electricity, but continued with percussion which sent

the crowd wild. The organisers convinced the police that the band should

continue to allow fans to wind down naturally—so the power was put back on! The

absence at such events of sound-checks (Hare krishna was a convenient one)

didn’t help either, especially for larger bands. But the Quins played happily

with very diverse groups such as the Who more than once, Roxy Music, Mott the

Hoople, and Shakin’ Stevens. It’s rumoured that Pink Floyd avoided playing with

them because of their own audience reaction.

they appeared on successive days at two of the greatest festivals, at Bath (with

Fleetwood Mac, Soft Machine etc) and second-billing to Traffic on the final day

at the Hollywood (Midlands) Festival that had one of the most stellar bills

ever witnessed. This was filmed by Solus for an unfinished Beeb documentary,

though they broadcast them at the ubiquitous St.Pancras Hall for BBC2’s Disco

Two: Sounds On Saturday. Down the road at the Lyceum a new record attendance

was established. Though audiences

wouldn’t notice, festivals created a tricky problem to overcome. At Hollywood

they had to follow Black Sabbath, which Allan recalls was near-catastrophic

because the negative vibes didn’t help getting into their own mood. Due to come

on after Deep Purple—probably at Aachen in 1970—the Black (K)nighters went well

over time against etiquette, then Blackmore poured petrol on the stacks

requiring the fire brigade and police. Quintessence played 20 minutes before

the authorities cut the electricity, but continued with percussion which sent

the crowd wild. The organisers convinced the police that the band should

continue to allow fans to wind down naturally—so the power was put back on! The

absence at such events of sound-checks (Hare krishna was a convenient one)

didn’t help either, especially for larger bands. But the Quins played happily

with very diverse groups such as the Who more than once, Roxy Music, Mott the

Hoople, and Shakin’ Stevens. It’s rumoured that Pink Floyd avoided playing with

them because of their own audience reaction.

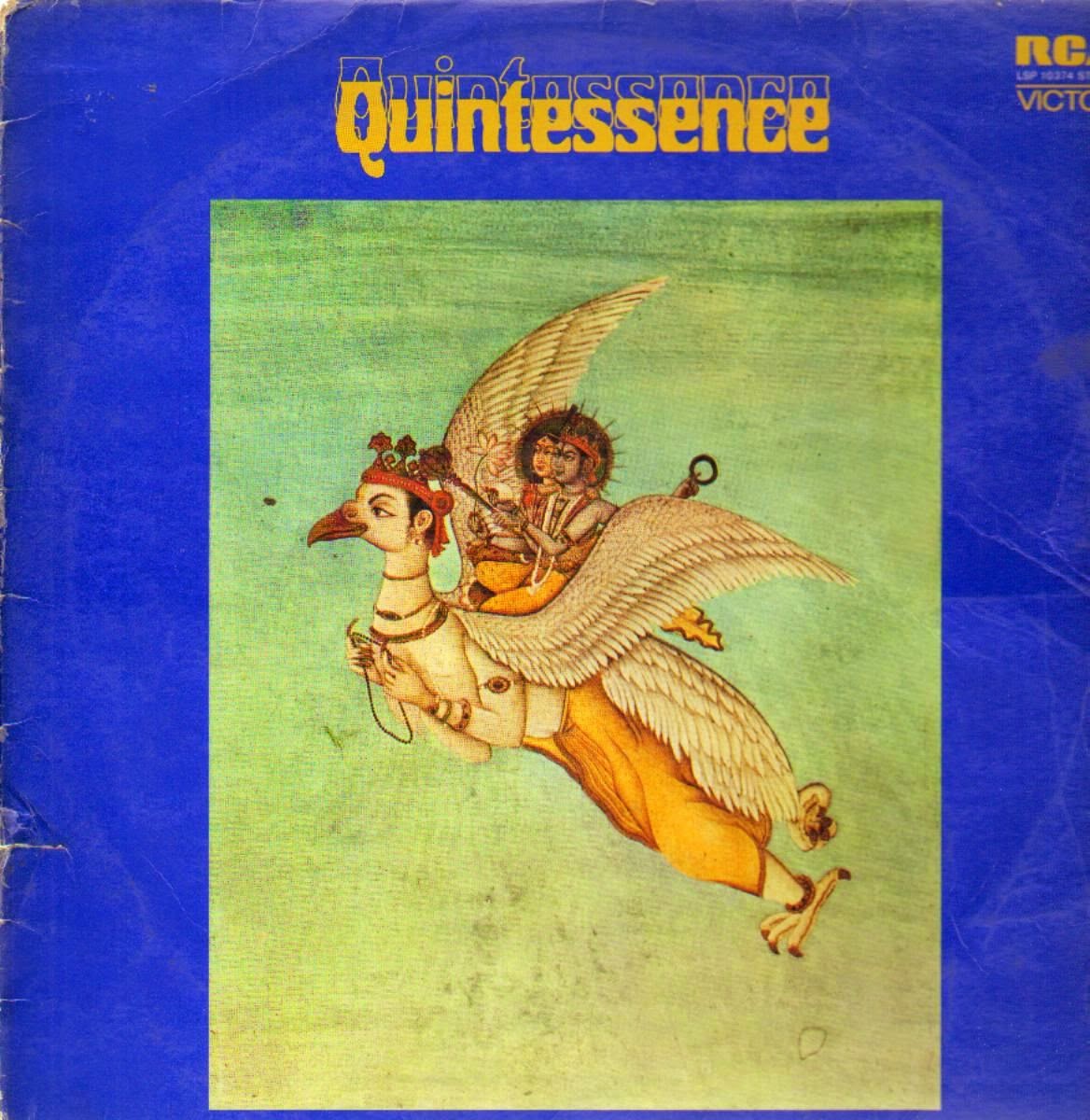

In June

Quintessence’s self-titled second album was released with reviews referring to

it by the back-cover’s motto: “Be This Dedicated To Our Lord Jesus”. Its lavish

multi-colour gatefold, designed by Gopal Das, was split-fronted to open into a

triptych as a shrine for candles and incense—if sounds quirky today, one might

wonder what purpose was intended for other covers?! The two album sleeves cost

Island £2,000, a huge amount then. The opener Jesus Buddha Moses Gauranga leads

into one of the most stunning guitar solos of the whole era, a classic acid-swirler

building to a head-topping crescendo on Sea Of Immortality live in the studio.

It fits well with Burning Bush and storming St. Pancras from that venue

capturing their fire (Jesus Buddha…live was put on the double-sampler Bumpers

and later a bonus track on Q’s CD). Interspersed with the confident rockers and

chants (Maha Mantra was recorded with the ashram choir; video of this recording

still exists) were instrumentals combining Indian instruments and electronics,

among the most atmospheric ambience yet recorded. Prisms, for instance, was

among the pioneer multi-recordings.

Quintessence’s self-titled second album was released with reviews referring to

it by the back-cover’s motto: “Be This Dedicated To Our Lord Jesus”. Its lavish

multi-colour gatefold, designed by Gopal Das, was split-fronted to open into a

triptych as a shrine for candles and incense—if sounds quirky today, one might

wonder what purpose was intended for other covers?! The two album sleeves cost

Island £2,000, a huge amount then. The opener Jesus Buddha Moses Gauranga leads

into one of the most stunning guitar solos of the whole era, a classic acid-swirler

building to a head-topping crescendo on Sea Of Immortality live in the studio.

It fits well with Burning Bush and storming St. Pancras from that venue

capturing their fire (Jesus Buddha…live was put on the double-sampler Bumpers

and later a bonus track on Q’s CD). Interspersed with the confident rockers and

chants (Maha Mantra was recorded with the ashram choir; video of this recording

still exists) were instrumentals combining Indian instruments and electronics,

among the most atmospheric ambience yet recorded. Prisms, for instance, was

among the pioneer multi-recordings.

Every title

describes what the song is about and intended to achieve. The first two albums

highlight the production and tighter arrangements of John Barham, a classically

trained composer with several film scores to his credit (Preminger, Jodorowsky)

who also worked with Ravi Shankar and George Harrison’s Wonder Wall and All

Things Must Pass projects. He released his own album Jugalbandi (Elektra 1973)

with Ashish Khan. His first Quintessence session had to be interrupted when he

and the drummer indulged in a more potent than usual hash cake! In a recent

interview Barham said he’d bought again all Quintessence’s work on CD. The

album was their most successful, reaching #22 during four weeks in the charts.

describes what the song is about and intended to achieve. The first two albums

highlight the production and tighter arrangements of John Barham, a classically

trained composer with several film scores to his credit (Preminger, Jodorowsky)

who also worked with Ravi Shankar and George Harrison’s Wonder Wall and All

Things Must Pass projects. He released his own album Jugalbandi (Elektra 1973)

with Ashish Khan. His first Quintessence session had to be interrupted when he

and the drummer indulged in a more potent than usual hash cake! In a recent

interview Barham said he’d bought again all Quintessence’s work on CD. The

album was their most successful, reaching #22 during four weeks in the charts.

Mixing of studio

and live exemplified their energetic improvisation; each song had a beginning

and end with lyrics and jamming as a bridge. Before a gig they drew straws to

see who led certain songs, creating freshness for them and the audience. No two

concerts were the same. Raja Ram graphically described it as “like letting a

tree grow: you prune it, tend it carefully, cut out the rotten parts, and don’t

put too much manure round the bottom!” The collective result was compared to

Grateful Dead—Mostert too was linked to Jerry Garcia; both used modal

scales—but their repertoire was wider. Flute and bass fused Indian and jazz

which, combined with subtle blues or acid guitar and choir-like range of the

vocals, sparked a trance-like experience, a truly cosmic trip.

and live exemplified their energetic improvisation; each song had a beginning

and end with lyrics and jamming as a bridge. Before a gig they drew straws to

see who led certain songs, creating freshness for them and the audience. No two

concerts were the same. Raja Ram graphically described it as “like letting a

tree grow: you prune it, tend it carefully, cut out the rotten parts, and don’t

put too much manure round the bottom!” The collective result was compared to

Grateful Dead—Mostert too was linked to Jerry Garcia; both used modal

scales—but their repertoire was wider. Flute and bass fused Indian and jazz

which, combined with subtle blues or acid guitar and choir-like range of the

vocals, sparked a trance-like experience, a truly cosmic trip.

Raja Ram and Shiva in 1969

Straight from the

studio they headlined at London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall with tour prices (even

at civic halls) kept as low as possible, sometimes only 50 pence. After a

Dudley Zoo bash in aid of the WWF, they took the same stage as Floyd, Soft

Machine, Santana, Jefferson Airplane, Canned Heat and T. Rex in front of

100,000 heads at Kralingen in Holland. Their track Giants exists separately to

the festival film Stomping Ground. Rave reviews in Switzerland, France (including

a circus event!) and Germany (two T.V. slots) culminated at the Aachen

Festival, probably the greatest ever on the European continent, with

Traffic, Deep Purple, If, Free, Floyd,

VDGG, Taste, Kraftwerk, Can, Amon Duul, Krokodil and many others. In July a

Sounds of the Seventies session was recorded at the Aeolian Hall and aired

twice (the same rare accolade repeated a few months later) then at the Paris

Hall for Sunday Concert with John Peel (there’s an odd absence from his shows).

Origins weren’t forgotten for a free concert outside Wormwood Scrubs prison

with Hawkwind and prominent placing on the first Glastonbury Festival attended

by 1,500 people when performers were paid the princely sum of 15 quid.

Recording then started for their next album.

studio they headlined at London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall with tour prices (even

at civic halls) kept as low as possible, sometimes only 50 pence. After a

Dudley Zoo bash in aid of the WWF, they took the same stage as Floyd, Soft

Machine, Santana, Jefferson Airplane, Canned Heat and T. Rex in front of

100,000 heads at Kralingen in Holland. Their track Giants exists separately to

the festival film Stomping Ground. Rave reviews in Switzerland, France (including

a circus event!) and Germany (two T.V. slots) culminated at the Aachen

Festival, probably the greatest ever on the European continent, with

Traffic, Deep Purple, If, Free, Floyd,

VDGG, Taste, Kraftwerk, Can, Amon Duul, Krokodil and many others. In July a

Sounds of the Seventies session was recorded at the Aeolian Hall and aired

twice (the same rare accolade repeated a few months later) then at the Paris

Hall for Sunday Concert with John Peel (there’s an odd absence from his shows).

Origins weren’t forgotten for a free concert outside Wormwood Scrubs prison

with Hawkwind and prominent placing on the first Glastonbury Festival attended

by 1,500 people when performers were paid the princely sum of 15 quid.

Recording then started for their next album.

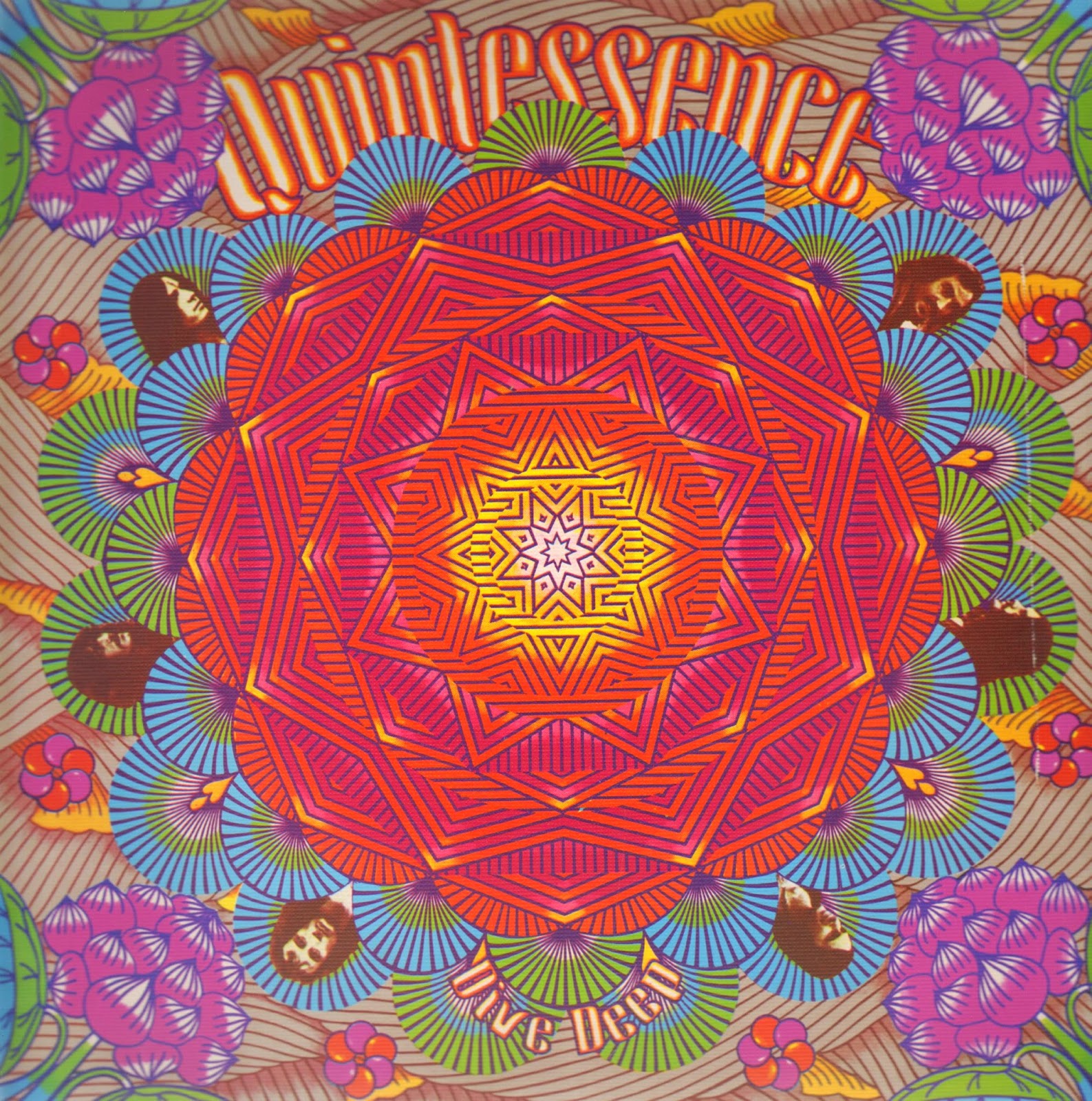

In March 1971 Dive

Deep was “dedicated to the Divine Mother of the Universe”. With a multi-colour

mandala and ecumenical shrine on the reverse, it reached #43. Again Allan

Mostert’s sitar and vina highlighted his multi-instrumentalism, a winning formula

that this time left out live material for a more meditative approach. The

summer saw another shift in approach, coinciding with less touring when Circle

Management took over (and later organised a cathedral tour).

Deep was “dedicated to the Divine Mother of the Universe”. With a multi-colour

mandala and ecumenical shrine on the reverse, it reached #43. Again Allan

Mostert’s sitar and vina highlighted his multi-instrumentalism, a winning formula

that this time left out live material for a more meditative approach. The

summer saw another shift in approach, coinciding with less touring when Circle

Management took over (and later organised a cathedral tour).

© Jane Stevenson

The band was now

able to afford a full P.A. and microphone system which brought new logistics to

the six-piece. The guitar volume had been the standard 7-10 max and this needed

turning down to a more manageable 1.5-2 volume. The wild guitar was thus

removed—by this time Mostert preferred a less distorted sound favoured by the

Grateful Dead and The Band anyway—but allowed vocals, flute and hand-percussion

to be more clearly heard. Audiences assumed Shiva and Ram were the band-leaders

but that was only because they could move around the stage more easily; there

was no upstaging. As festival footage shows, sometimes their stagecraft had the

drummer centre-front with the guitarists behind. Integral to the free-form

style was being able to attune to where the others were taking songs for the

collective mix.

able to afford a full P.A. and microphone system which brought new logistics to

the six-piece. The guitar volume had been the standard 7-10 max and this needed

turning down to a more manageable 1.5-2 volume. The wild guitar was thus

removed—by this time Mostert preferred a less distorted sound favoured by the

Grateful Dead and The Band anyway—but allowed vocals, flute and hand-percussion

to be more clearly heard. Audiences assumed Shiva and Ram were the band-leaders

but that was only because they could move around the stage more easily; there

was no upstaging. As festival footage shows, sometimes their stagecraft had the

drummer centre-front with the guitarists behind. Integral to the free-form

style was being able to attune to where the others were taking songs for the

collective mix.

Exploring rock

motifs with other styles resulted in extended three-hour shows with

twenty-minute encores. A gig with Hare Krishna devotees could be followed by

the ashram choir, or Allan on sitar with friends as an opener. I recall this at

the Friends (Quaker) Hall in Euston Road when equally split between ragas and

electric, with tapestries draped over the amps and light-show by the legendary

Barney Bubbles (1942-83) completing the ambience. A school-friend of Allan’s,

Ned Bladen, guested on tablas and became a feature when the sound became more

percussion-driven, as on Dive Deep and Glastonbury ’71 surrounding the double

bass-drum with Jake Milton an underrated master in rhythm patterns. A promo

leaflet called it music and lights from the spheres.

motifs with other styles resulted in extended three-hour shows with

twenty-minute encores. A gig with Hare Krishna devotees could be followed by

the ashram choir, or Allan on sitar with friends as an opener. I recall this at

the Friends (Quaker) Hall in Euston Road when equally split between ragas and

electric, with tapestries draped over the amps and light-show by the legendary

Barney Bubbles (1942-83) completing the ambience. A school-friend of Allan’s,

Ned Bladen, guested on tablas and became a feature when the sound became more

percussion-driven, as on Dive Deep and Glastonbury ’71 surrounding the double

bass-drum with Jake Milton an underrated master in rhythm patterns. A promo

leaflet called it music and lights from the spheres.

Tony Stewart

(Sounds Feb. 1971) pointed out that some bands settled into an easy pattern of

giving audiences what was expected without variation due to critics’ need to

pigeon-hole groups, but Quintessence was an extension of their individual personalities

representing the position reached in their own existence, what another scribe

described as “the first musicians to dedicate their music to God since Haydn”.

It was “a subtle, tasteful blend of most of today’s musical styles”, “a

soul-enriching experience quite unforgettable… for those in blissful company,

thanks to Quintessence”, not the usual critics’ response to be sure. Concerts

were total experiences on several levels but sometimes had quirky side-effects,

as when banned from Bristol’s Colston Hall because joss sticks deemed a fire

hazard to be confiscated—cigarettes however were allowed. The same happened at

London’s Speakeasy club.

(Sounds Feb. 1971) pointed out that some bands settled into an easy pattern of

giving audiences what was expected without variation due to critics’ need to

pigeon-hole groups, but Quintessence was an extension of their individual personalities

representing the position reached in their own existence, what another scribe

described as “the first musicians to dedicate their music to God since Haydn”.

It was “a subtle, tasteful blend of most of today’s musical styles”, “a

soul-enriching experience quite unforgettable… for those in blissful company,

thanks to Quintessence”, not the usual critics’ response to be sure. Concerts

were total experiences on several levels but sometimes had quirky side-effects,

as when banned from Bristol’s Colston Hall because joss sticks deemed a fire

hazard to be confiscated—cigarettes however were allowed. The same happened at

London’s Speakeasy club.

Apart from another

BBC2 TV appearance and the Camden Festival that combined music with films, the

band rested until the second Glastonbury Festival in June where Freedom appears

in the film of the by-now famous event. (They even helped to build its famous

pyramid stage.) London Weekend Television filmed them in the studio for their

awful-titled God Rock series broadcast in July, one of the band playing a

different instrument in protest against having to mime (only the vocals were

live). A German tour was followed by the legendary Weeley Festival, whose

line-up simply beggars belief, and a Bangladesh benefit at the Oval sports

ground with The Who and Faces which turned out to be the mighty Quins’ last

festival show.

BBC2 TV appearance and the Camden Festival that combined music with films, the

band rested until the second Glastonbury Festival in June where Freedom appears

in the film of the by-now famous event. (They even helped to build its famous

pyramid stage.) London Weekend Television filmed them in the studio for their

awful-titled God Rock series broadcast in July, one of the band playing a

different instrument in protest against having to mime (only the vocals were

live). A German tour was followed by the legendary Weeley Festival, whose

line-up simply beggars belief, and a Bangladesh benefit at the Oval sports

ground with The Who and Faces which turned out to be the mighty Quins’ last

festival show.

By then Island

despaired of a hit and a majority vote of the band rejected their US deal with

Bell (Island’s famous Bumpers wasn’t even issued in the US), so switched to RCA

in the hope of a first stateside tour. A new single, the non-album Sweet Jesus

/ You Never Stay The Same (a different mix to the LP) was brought out on the

subsidiary Neon in November.

despaired of a hit and a majority vote of the band rejected their US deal with

Bell (Island’s famous Bumpers wasn’t even issued in the US), so switched to RCA

in the hope of a first stateside tour. A new single, the non-album Sweet Jesus

/ You Never Stay The Same (a different mix to the LP) was brought out on the

subsidiary Neon in November.

This was double-edged as Neon never had enough

backing for just eleven LPs and a minor hit single in its one year existence.

Quintessence were disappointed, Shiva recalls, “not a smart decision on [RCA’s]

part”, and certainly deserved more as an international name-band. In December

they were recorded by RCA at Exeter University, then headlined a sell-out

6,000-seater Royal Albert Hall for what was to be the high watermark. The

ashram choir shared the stage—just as well the venue had its own backstage

cook—while in the audience was the ambassador of India and president of RCA,

who said he wanted them to play the equivalent Carnegie Hall.

backing for just eleven LPs and a minor hit single in its one year existence.

Quintessence were disappointed, Shiva recalls, “not a smart decision on [RCA’s]

part”, and certainly deserved more as an international name-band. In December

they were recorded by RCA at Exeter University, then headlined a sell-out

6,000-seater Royal Albert Hall for what was to be the high watermark. The

ashram choir shared the stage—just as well the venue had its own backstage

cook—while in the audience was the ambassador of India and president of RCA,

who said he wanted them to play the equivalent Carnegie Hall.

Early 1972 saw

dates in Europe (Zurich was recorded and privately issued), Scandinavia and

another Sounds of the Seventies. The same month that the BBC broadcast them at

Norwich Cathedral, Self was released in June to critical acclaim. Partly

recorded before Dive Deep, some of their finest work opens with Cosmic Surfer

(a modern take on God as cosmic dancer), the classic single never issued.

Somebody else had the same idea: there exists a two-sided acetate of it b/w

Wonders Of The Universe, mysteriously with Apple Corps Ltd on the white and

green label. Did someone approach George Harrison before signing the contract

to RCA? For the album the guitarist’s favourite solo appears on his composition

Vishnu Narain, and Raja Ram experiments with wah-wah pedal for flute. The

bassist thought the live second vinyl side was an average gig but the confident

energy shows them at their peak (the 14-minute Water Goddess is a retitled

Ganga Mai). New Musical Express welcomed their extended live sound at last for

“a remarkable album [that] illustrates their strength as songwriters with the

studio side,” a fair statement that the label reprinted for a Rolling Stone ad.

The album immediately entered at #50 for one week then inexplicably disappeared

from the ratings.

dates in Europe (Zurich was recorded and privately issued), Scandinavia and

another Sounds of the Seventies. The same month that the BBC broadcast them at

Norwich Cathedral, Self was released in June to critical acclaim. Partly

recorded before Dive Deep, some of their finest work opens with Cosmic Surfer

(a modern take on God as cosmic dancer), the classic single never issued.

Somebody else had the same idea: there exists a two-sided acetate of it b/w

Wonders Of The Universe, mysteriously with Apple Corps Ltd on the white and

green label. Did someone approach George Harrison before signing the contract

to RCA? For the album the guitarist’s favourite solo appears on his composition

Vishnu Narain, and Raja Ram experiments with wah-wah pedal for flute. The

bassist thought the live second vinyl side was an average gig but the confident

energy shows them at their peak (the 14-minute Water Goddess is a retitled

Ganga Mai). New Musical Express welcomed their extended live sound at last for

“a remarkable album [that] illustrates their strength as songwriters with the

studio side,” a fair statement that the label reprinted for a Rolling Stone ad.

The album immediately entered at #50 for one week then inexplicably disappeared

from the ratings.

And then a

bombshell hit. Without notice, Shiva and Maha Dev were sacked that month when

the vocalist was the iconic frontman and guitarist receiving plaudits as one of

the country’s unsung aces. It seems ironical that the pair had been the only

ones who voted for Island’s US deal when all their contemporaries had deals

there, so “we were out in the cold as it were”.

Some were pulling in different directions by then, when increasingly

loose jamming required chanting as the rhythm section never established a modus

operandi to get out of the occasional cul-de-sac.

bombshell hit. Without notice, Shiva and Maha Dev were sacked that month when

the vocalist was the iconic frontman and guitarist receiving plaudits as one of

the country’s unsung aces. It seems ironical that the pair had been the only

ones who voted for Island’s US deal when all their contemporaries had deals

there, so “we were out in the cold as it were”.

Some were pulling in different directions by then, when increasingly

loose jamming required chanting as the rhythm section never established a modus

operandi to get out of the occasional cul-de-sac.

Raja Ram claimed

that after two managers there was a £13,000 debt in spite of their hard work,

so perhaps it was an attempt to streamline costs (though Shiva never got his

keyboards, congas or even microphone back). But they had also received a

substantial advance from RCA, by which time Ram had moved out of the Grove to

Kensington. His wife Sita took over bookings and the quartet raised their fee

for what was described as “more celestial, spacey and musically economical”.

When the four-piece turned up at venues they were asked “Where’s the singer?”

because there was no official press release. Lined-up to conclude Reading

Festival in August, Ten Years After lived up to their name so no time was left

for the headliners!

that after two managers there was a £13,000 debt in spite of their hard work,

so perhaps it was an attempt to streamline costs (though Shiva never got his

keyboards, congas or even microphone back). But they had also received a

substantial advance from RCA, by which time Ram had moved out of the Grove to

Kensington. His wife Sita took over bookings and the quartet raised their fee

for what was described as “more celestial, spacey and musically economical”.

When the four-piece turned up at venues they were asked “Where’s the singer?”

because there was no official press release. Lined-up to conclude Reading

Festival in August, Ten Years After lived up to their name so no time was left

for the headliners!

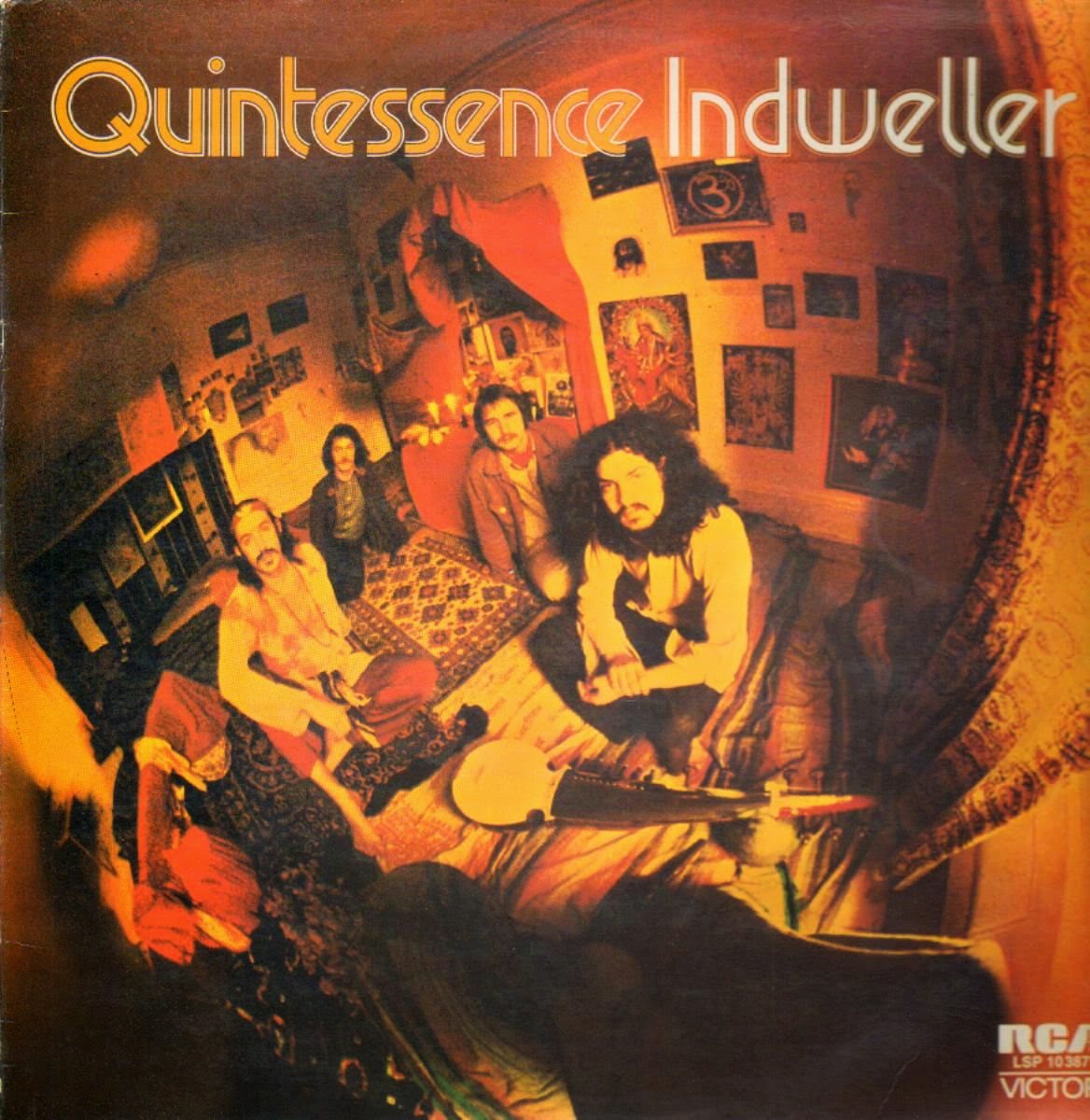

The new album

Indweller was released in December on RCA proper but, for the first time since

the debut, failed to chart in spite of a tour in February. Previously sales

were steady and good enough to delay recording the next LP, but this changed in

the RCA days. The 10 tracks were in the same mode but missed a stand-out track

along with the variety and depth of the absent vocalist and guitarist. Ram

admitted that the band “staggered on”, Sita sometimes joining on keyboards, until

fizzling out somewhere in Germany in 1980. Jake Milton—who stayed on the fringe

of the band’s spirituality—formed an avant-garde punk-jazz trio Blurt with his

brother Ted, to rave reviews like NME saying they blew Joy Division off-stage.

Mixed with existentialist poetry inspired by Bukowski and compared to Beefheart

and Waits, they recorded three studio and a live in Berlin for Factory Records.

Indweller was released in December on RCA proper but, for the first time since

the debut, failed to chart in spite of a tour in February. Previously sales

were steady and good enough to delay recording the next LP, but this changed in

the RCA days. The 10 tracks were in the same mode but missed a stand-out track

along with the variety and depth of the absent vocalist and guitarist. Ram

admitted that the band “staggered on”, Sita sometimes joining on keyboards, until

fizzling out somewhere in Germany in 1980. Jake Milton—who stayed on the fringe

of the band’s spirituality—formed an avant-garde punk-jazz trio Blurt with his

brother Ted, to rave reviews like NME saying they blew Joy Division off-stage.

Mixed with existentialist poetry inspired by Bukowski and compared to Beefheart

and Waits, they recorded three studio and a live in Berlin for Factory Records.

Within weeks Phil

and Dave formed Kala, named after a manifestation of Shiva, and able to display

their own tour bus in the Grove. Phil even appeared in one of Michael Caine’s

films when a new friend turned out to be his manager needing a long-haired

hippy! Circle Management contacted the guitarist saying that ELO wanted to

recruit him but he was already committed to Kala who’d signed to Bradley’s

Records, a subsidiary of ATV. Agents, however, were loath to book them because

Phil’s absence from Quintessence was misinterpreted as blowing out gigs when in

fact due to the mismanagement of Ram. It speaks volumes that, with many friends

from the ’60s, the singer hasn’t spoken to him since the day he heard the news.

and Dave formed Kala, named after a manifestation of Shiva, and able to display

their own tour bus in the Grove. Phil even appeared in one of Michael Caine’s

films when a new friend turned out to be his manager needing a long-haired

hippy! Circle Management contacted the guitarist saying that ELO wanted to

recruit him but he was already committed to Kala who’d signed to Bradley’s

Records, a subsidiary of ATV. Agents, however, were loath to book them because

Phil’s absence from Quintessence was misinterpreted as blowing out gigs when in

fact due to the mismanagement of Ram. It speaks volumes that, with many friends

from the ’60s, the singer hasn’t spoken to him since the day he heard the news.

Kala issued one

eponymous LP and 7” in 1973. Some songs originally earmarked for Quintessence

were now in a more structured form Shiva told me: “Kala has tighter

arrangements and a stronger rock feel. I wrote songs that could not be

performed by Quintessence and that allowed me to use my voice in a different

way, tapping into my blues and rock roots”. The sound partly reprised his early

years in Australia with a blues and slightly country influence, overlaid with

more generally spiritual lyrics. In the late sixties he liked Steve Marriott’s

Small Faces, Yardbirds, Zombies, Animals, Hendrix and The Band after buying as

a teenager the latest records of Roy Orbison, the Everly Brothers and Beatles.

“The moving into blues and R & B brought me to my style in Quintessence”

that’s remained ever since, a breadth shown as a big fan still of Dion, Nat

King Cole and Del Shannon among many others, along with early Baroque and also

Indian classical music. This eclecticism is a trait of most of the great

singers in popular music’s history. Perhaps surprisingly, he no longer has any

vinyl or even his own recordings, “things seem to disappear as time goes by”.

eponymous LP and 7” in 1973. Some songs originally earmarked for Quintessence

were now in a more structured form Shiva told me: “Kala has tighter

arrangements and a stronger rock feel. I wrote songs that could not be

performed by Quintessence and that allowed me to use my voice in a different

way, tapping into my blues and rock roots”. The sound partly reprised his early

years in Australia with a blues and slightly country influence, overlaid with

more generally spiritual lyrics. In the late sixties he liked Steve Marriott’s

Small Faces, Yardbirds, Zombies, Animals, Hendrix and The Band after buying as

a teenager the latest records of Roy Orbison, the Everly Brothers and Beatles.

“The moving into blues and R & B brought me to my style in Quintessence”

that’s remained ever since, a breadth shown as a big fan still of Dion, Nat

King Cole and Del Shannon among many others, along with early Baroque and also

Indian classical music. This eclecticism is a trait of most of the great

singers in popular music’s history. Perhaps surprisingly, he no longer has any

vinyl or even his own recordings, “things seem to disappear as time goes by”.

He produced the

Kala album at three studios with John Barham, who’d been sidelined from Q’s

later albums by Ram. Guests included Carol Grimes and, in unfortunate

circumstances, Les Nichols (Methuselah, Pavlov’s Dog, Leo Sayer etc) replaced

Codling. For the first time each got their own writing credits since

Quintessence had a policy of group compositions irrespective of individual

contributions. The writing was on the wall, however, when the label illicitly

replaced the LP’s eastern cover with a self-detested promo-image of the singer.

After Codling, the band demanded more than their 300 quid a week so, due to a

lucky coincidence, were replaced with visiting members from his Unknown Blues

for a tour which featured on a live sampler Bradley’s Roadshow with Paul Brett’s

Sage and Hunter Muskett, the three bands chosen to launch the label. Recorded

at the Marquee in March 1973 and produced by Keith Relf of The Yardbirds and

Medicine Head fame, it remained hard to find.

Kala album at three studios with John Barham, who’d been sidelined from Q’s

later albums by Ram. Guests included Carol Grimes and, in unfortunate

circumstances, Les Nichols (Methuselah, Pavlov’s Dog, Leo Sayer etc) replaced

Codling. For the first time each got their own writing credits since

Quintessence had a policy of group compositions irrespective of individual

contributions. The writing was on the wall, however, when the label illicitly

replaced the LP’s eastern cover with a self-detested promo-image of the singer.

After Codling, the band demanded more than their 300 quid a week so, due to a

lucky coincidence, were replaced with visiting members from his Unknown Blues

for a tour which featured on a live sampler Bradley’s Roadshow with Paul Brett’s

Sage and Hunter Muskett, the three bands chosen to launch the label. Recorded

at the Marquee in March 1973 and produced by Keith Relf of The Yardbirds and

Medicine Head fame, it remained hard to find.

Probably

unsurprisingly for a label named after a hotelier, policy soon changed to a

preference for singles and Shiva to jump aboard the glam bandwagon. He recently

told Professor Cornelius, “The thought of putting on a glitter suit and copying

the trends of the time was nauseating to me. I just couldn’t go from the

creative expression of Quintessence to that… Money and fame weren’t my

motivation”. So Bradley’s took the van and equipment back from outside their

Blenheim Crescent home in a fit of pique and refused to release him from his

contract, forcing him to work in a rural dairy farm without other means of

livelihood. The Goodies (who did an asinine anti-Krishna ditty on their

Dandelion single) and Sweet Dreams provided the label’s hit-fodder until it

ceased in 1977, as unnoticed as their roster in the media during its tenure. In

2010 Hux Records issued The Complete Kala Recordings remastered with two new

mixes, unreleased live songs, and an informative booklet of the fine band’s

ill-fated brief history.

unsurprisingly for a label named after a hotelier, policy soon changed to a

preference for singles and Shiva to jump aboard the glam bandwagon. He recently

told Professor Cornelius, “The thought of putting on a glitter suit and copying

the trends of the time was nauseating to me. I just couldn’t go from the

creative expression of Quintessence to that… Money and fame weren’t my

motivation”. So Bradley’s took the van and equipment back from outside their

Blenheim Crescent home in a fit of pique and refused to release him from his

contract, forcing him to work in a rural dairy farm without other means of

livelihood. The Goodies (who did an asinine anti-Krishna ditty on their

Dandelion single) and Sweet Dreams provided the label’s hit-fodder until it

ceased in 1977, as unnoticed as their roster in the media during its tenure. In

2010 Hux Records issued The Complete Kala Recordings remastered with two new

mixes, unreleased live songs, and an informative booklet of the fine band’s

ill-fated brief history.

Quintessence’s

albums are rarely out-of-print somewhere in the world. A compilation Epitaph

For Tomorrow was made by Edsel in 1994, and Island issued Oceans Of Bliss

which, incredibly, omitted the stunning Sea Of Immortality. Drop Out released

Self and Indweller (1995) as a twofer with one track missing that shouldn’t

have been, Sai Baba, which extends their pantheon. In 2009 the consistently

excellent Hux—their booklets are essential reading—resuscitated the legendary

St. Pancras 1970 concert, i.e. the material left off the second LP. Cosmic

Energy has a 20-minute Giants Suite in full-flow plus five early and new songs

from the Queen Elizabeth Hall a year later. Released simultaneously was

Infinite Love, the rest of the second show from two same-day solo performances.

Over 2½ hours of prime Quintessence on a double CD captures them at full tilt

with favourites varying in style and length each time. This fine cross-section,

which omits Wonders Of The Universe because blighted by an out of tune bass,

includes the only recording of Meditations before the Kala LP. Why Island

didn’t issue it as a live double to recoup outlay remains a conundrum. “In

those days the music press was all-powerful,” recalled Chris Welch, “I

earnestly commended the populace to see them [and] flew in the face of prevailing

opinion when daring to proclaim they were better live than the Doors”.

albums are rarely out-of-print somewhere in the world. A compilation Epitaph

For Tomorrow was made by Edsel in 1994, and Island issued Oceans Of Bliss

which, incredibly, omitted the stunning Sea Of Immortality. Drop Out released

Self and Indweller (1995) as a twofer with one track missing that shouldn’t

have been, Sai Baba, which extends their pantheon. In 2009 the consistently

excellent Hux—their booklets are essential reading—resuscitated the legendary

St. Pancras 1970 concert, i.e. the material left off the second LP. Cosmic

Energy has a 20-minute Giants Suite in full-flow plus five early and new songs

from the Queen Elizabeth Hall a year later. Released simultaneously was

Infinite Love, the rest of the second show from two same-day solo performances.

Over 2½ hours of prime Quintessence on a double CD captures them at full tilt

with favourites varying in style and length each time. This fine cross-section,

which omits Wonders Of The Universe because blighted by an out of tune bass,

includes the only recording of Meditations before the Kala LP. Why Island

didn’t issue it as a live double to recoup outlay remains a conundrum. “In

those days the music press was all-powerful,” recalled Chris Welch, “I

earnestly commended the populace to see them [and] flew in the face of prevailing

opinion when daring to proclaim they were better live than the Doors”.

Their later

careers continue to be creative. Raja Ram turned to the electronics of

psy-trance and strutting histrionics of Shpongle in Arthur Brown-like

flamboyance, where the lasers, smoke and mirrors reflect his personality in

interviews as if reverting back to pre-Q Roland. Maha Dev briefly formed

Samsara then released a solo album before moving to America and various music

projects. After returning home he formed a new Quintessence recapturing the

original ethos. Initially auditioning on bass before switching, Allan Mostert’s

spontaneous styles avoided cliché yet he’s one of the period’s most underrated

guitarists, reflected in the Melody Maker review of the second album: “Its main

function will be to elevate the lead guitarist to hero status”. An early

Hendrix influence changed when Jake brought the latest Grateful Dead LPs to the

house. His subsequent career developed as a vocalist with the ’90s trio

Blissticket that evolved from a heavy acid grunge (Brave New World) to a more

JJ Cale-feel on Magic Love. Prana (Monsoon Moon, Wirikuta Healing) culminated

with Inside World on Burning Shed Records in 2003. The multi-instrumentalist

lives today in Spain and as a duo with his wife plays at world music concerts.

careers continue to be creative. Raja Ram turned to the electronics of

psy-trance and strutting histrionics of Shpongle in Arthur Brown-like

flamboyance, where the lasers, smoke and mirrors reflect his personality in

interviews as if reverting back to pre-Q Roland. Maha Dev briefly formed

Samsara then released a solo album before moving to America and various music

projects. After returning home he formed a new Quintessence recapturing the

original ethos. Initially auditioning on bass before switching, Allan Mostert’s

spontaneous styles avoided cliché yet he’s one of the period’s most underrated

guitarists, reflected in the Melody Maker review of the second album: “Its main

function will be to elevate the lead guitarist to hero status”. An early

Hendrix influence changed when Jake brought the latest Grateful Dead LPs to the

house. His subsequent career developed as a vocalist with the ’90s trio

Blissticket that evolved from a heavy acid grunge (Brave New World) to a more

JJ Cale-feel on Magic Love. Prana (Monsoon Moon, Wirikuta Healing) culminated

with Inside World on Burning Shed Records in 2003. The multi-instrumentalist

lives today in Spain and as a duo with his wife plays at world music concerts.

In the ’80s Phil

Shiva Shankar Jones almost signed to Elektra for his Room 101 band. In 1995 he

moved to New Mexico (which once attracted D.H.Lawrence and Malcolm Lowry for

different reasons, and where Shambhu had lived since the ’70s) for a new path

as a sound vibration therapist and inner faith minister—with a difference.

Since schooldays he had Aboriginal friends and, after England, interest in

their unique didgeridoo rekindled, in fact transformed his life he says.

Touring America he links the didge with its (and his) spiritual origins as The

Yoga of Breath and Sound—the instrument is a logical extension of breath

control that underpins all yogic meditation and, of course, fine singing—for

workshops at universities, churches, meditation groups, hospitals and

alternative health centres. This uniquely personal yet shared creativity

recalls Swami Ambikananda’s “Find your purpose in life and fulfil it.” Some of

Quintessence still stay true to their beliefs as a process of selection, the

fruit of a lifetime’s experience.

Shiva Shankar Jones almost signed to Elektra for his Room 101 band. In 1995 he

moved to New Mexico (which once attracted D.H.Lawrence and Malcolm Lowry for

different reasons, and where Shambhu had lived since the ’70s) for a new path

as a sound vibration therapist and inner faith minister—with a difference.

Since schooldays he had Aboriginal friends and, after England, interest in

their unique didgeridoo rekindled, in fact transformed his life he says.

Touring America he links the didge with its (and his) spiritual origins as The

Yoga of Breath and Sound—the instrument is a logical extension of breath

control that underpins all yogic meditation and, of course, fine singing—for

workshops at universities, churches, meditation groups, hospitals and

alternative health centres. This uniquely personal yet shared creativity

recalls Swami Ambikananda’s “Find your purpose in life and fulfil it.” Some of

Quintessence still stay true to their beliefs as a process of selection, the

fruit of a lifetime’s experience.

He has worked

with Rudra Beauvert, a highly-regarded musician in Switzerland for his

electronic projects on a kindred path. In 2003 they issued Shiva Shakti which

revisits five Quin classics beginning with the first single and new songs by

both composers, merging the inspirational sound of the east with the Euro-rock

innovation of the west. Two years later appeared the double CD Cosmic Surfer as

Shiva’s Quintessence. Maha Dev returns on guitar and vocals, plus guests from

America (Ronnie Levine; Jenny Bird etc.) and Shiva’s son Krishna Jones, who

also features in the acclaimed reunion of Unknown Blues. Side one addresses the

geo-political climate of global life, a warning message mixing humorous satire

with important views on today’s pervasive political/personal delusions when

narrow mind-sets fuel destructive, fear-based agendas. Change starts with the

individual.

with Rudra Beauvert, a highly-regarded musician in Switzerland for his

electronic projects on a kindred path. In 2003 they issued Shiva Shakti which

revisits five Quin classics beginning with the first single and new songs by

both composers, merging the inspirational sound of the east with the Euro-rock

innovation of the west. Two years later appeared the double CD Cosmic Surfer as

Shiva’s Quintessence. Maha Dev returns on guitar and vocals, plus guests from

America (Ronnie Levine; Jenny Bird etc.) and Shiva’s son Krishna Jones, who

also features in the acclaimed reunion of Unknown Blues. Side one addresses the

geo-political climate of global life, a warning message mixing humorous satire

with important views on today’s pervasive political/personal delusions when

narrow mind-sets fuel destructive, fear-based agendas. Change starts with the

individual.

Insightful tracks

(Reptilian Corporate Sign Language, Hollywood Guru Show, Everything Is Weird)

highlight truths in clever poetry that would grace any manifesto against

today’s conspiracy of alienation. New Age Breadhead may be a side-ways glance

to who broke-up the original band. Interspersed with ballads is Didgeridoo

Medicine Man, which reminds this reviewer of John Fiddler’s recent work: a

simmering boogie beat with meaningful sense-of-life lyrics. CD two returns to

the Quins’ song-book from Giants and Ganga Mai to Cosmic Surfer and Hallelujad.

Hail Mary and Sun were written for Quintessence but never recorded, the former

featured at the Albert Hall and the latter in Kala’s set-list. The chants are

some of the best anywhere, pure lifters for listeners seeking genuine

inspiration. An excellent compilation, with two new tracks, was issued as Shiva

Quintessence’s Only Love Can Save Us (Hux 2011).

(Reptilian Corporate Sign Language, Hollywood Guru Show, Everything Is Weird)

highlight truths in clever poetry that would grace any manifesto against

today’s conspiracy of alienation. New Age Breadhead may be a side-ways glance

to who broke-up the original band. Interspersed with ballads is Didgeridoo

Medicine Man, which reminds this reviewer of John Fiddler’s recent work: a

simmering boogie beat with meaningful sense-of-life lyrics. CD two returns to

the Quins’ song-book from Giants and Ganga Mai to Cosmic Surfer and Hallelujad.

Hail Mary and Sun were written for Quintessence but never recorded, the former

featured at the Albert Hall and the latter in Kala’s set-list. The chants are

some of the best anywhere, pure lifters for listeners seeking genuine

inspiration. An excellent compilation, with two new tracks, was issued as Shiva

Quintessence’s Only Love Can Save Us (Hux 2011).

In 2010 Rudra

Beauvert was instrumental in relinking Dave Maha Dev Codling’s new Quintessence

with Shiva as guest for a moving 40th anniversary Glastonbury Festival,

released as Rebirth (Hux) and once again produced by John Barham. Eight songs,

including the first single with added lyrics in a punchier boogie rhythm, are

featured with four new studio tracks entitled Sattvic Meditation Suite, where

the haunting When Thy Song Flows Through Me sets the scene for Glastonbury

Dawn, Sunrise, and Mendocino Bay. Rebirth is a fine revisit to the repertoire

of one of the leading bands of the era. The buzz of the occasion can be seen on

video at Mooncow and the Inside Out broadcast of November that year when Shiva

re-met Dave Codling (with the local BBC station) in Yorkshire after 35 years.

Beauvert was instrumental in relinking Dave Maha Dev Codling’s new Quintessence

with Shiva as guest for a moving 40th anniversary Glastonbury Festival,

released as Rebirth (Hux) and once again produced by John Barham. Eight songs,

including the first single with added lyrics in a punchier boogie rhythm, are

featured with four new studio tracks entitled Sattvic Meditation Suite, where

the haunting When Thy Song Flows Through Me sets the scene for Glastonbury

Dawn, Sunrise, and Mendocino Bay. Rebirth is a fine revisit to the repertoire

of one of the leading bands of the era. The buzz of the occasion can be seen on

video at Mooncow and the Inside Out broadcast of November that year when Shiva

re-met Dave Codling (with the local BBC station) in Yorkshire after 35 years.

In 2012 the

Unknown Blues reformed for two lauded shows at Australia’s prestigious Byron

Bay Bluesfest in front of over 100,000 people. The lead guitarist, Chris Brown,

had been in Kala at the Marquee and the friends first played music on the same

stage at the age of 15. Literary agents in New York have approached Phil for a

book of memoirs, meanwhile he is working on a new album with American guitarist

Frank Evans, Rudra Beauvert, and John Barham from the early days that may

appear later this year. “We are creating a nice energy together,” the singer

says, “with a spiritual coffee house vibe”, so it sounds well worth looking out

for.

Unknown Blues reformed for two lauded shows at Australia’s prestigious Byron

Bay Bluesfest in front of over 100,000 people. The lead guitarist, Chris Brown,

had been in Kala at the Marquee and the friends first played music on the same

stage at the age of 15. Literary agents in New York have approached Phil for a

book of memoirs, meanwhile he is working on a new album with American guitarist

Frank Evans, Rudra Beauvert, and John Barham from the early days that may

appear later this year. “We are creating a nice energy together,” the singer

says, “with a spiritual coffee house vibe”, so it sounds well worth looking out

for.

Every band story

has its highs and lows of course, but history as seen today has unjustly

side-lined acts like Quintessence while raising rather ordinary names, in stark

contrast to contemporary memories. There was originality in massive doses, so

when Cream, Taste, Beatles and Badfinger split no one would even think to clone

themselves as Curd, Tasty, Sadfinger or the Bootles ad nauseum. Other names

also define the epoch. In 1970-72 Quintessence appeared in the five leading

music magazines regularly with no less than three dozen interviews and concert

reviews alone, plus Zig Zag, Beat Instrumental and several underground

periodicals as well as the infamous News Of The World. The sensation of 1970

euro-debuted at Montreux, sold out the Albert Hall single-handedly, and graced

the inaugural Glastonburys, where their return as special guests for the 40th

anniversary is a testament to their standing.

has its highs and lows of course, but history as seen today has unjustly

side-lined acts like Quintessence while raising rather ordinary names, in stark

contrast to contemporary memories. There was originality in massive doses, so

when Cream, Taste, Beatles and Badfinger split no one would even think to clone

themselves as Curd, Tasty, Sadfinger or the Bootles ad nauseum. Other names

also define the epoch. In 1970-72 Quintessence appeared in the five leading

music magazines regularly with no less than three dozen interviews and concert

reviews alone, plus Zig Zag, Beat Instrumental and several underground

periodicals as well as the infamous News Of The World. The sensation of 1970

euro-debuted at Montreux, sold out the Albert Hall single-handedly, and graced