Alec Palao, Man Of Many Musical Hats

Alec, thanks for taking the time to share your musical journey with “It’s Psychedelic Baby Magazine” readers. You are recognized by music fans for your prowess at conceiving and producing reissues and compilations, searching tape vaults, annotating tracks and writing liner notes for releases, as being a top notch sound engineer, and as Jymn Parrett of the “Garage Punk Hideout” has commented “Alec Palao is one of rock’s great gentlemen.”

When were you born and where did you grow up? What role did music play in the Palao household?

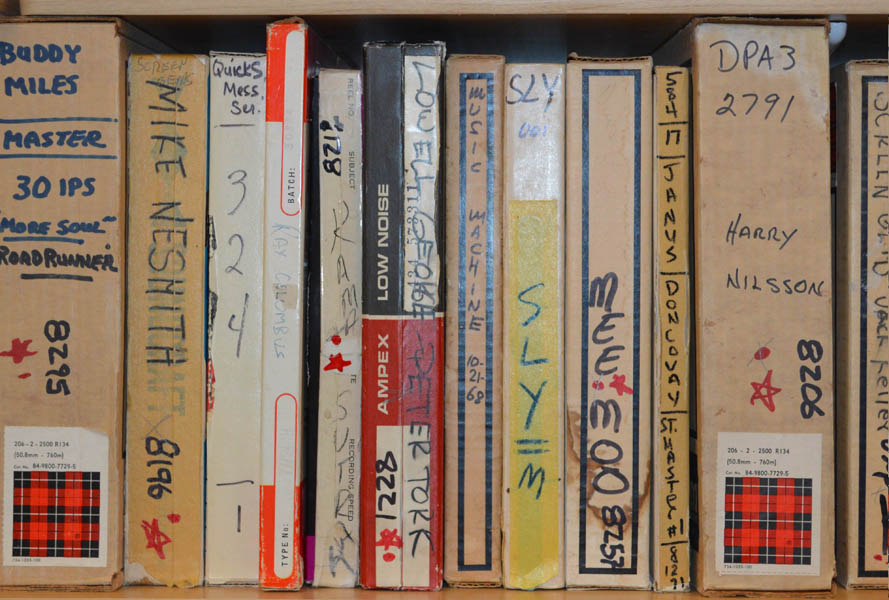

Born in north London, just as ‘Love Me Do’ was entering the UK charts in late 1962 so you could say I was “subliminally programmed.” My dad loved pop music and so I was aware of it more or less from birth. He fancied himself a bit of a DJ and so he had two record decks and a Ferrograph (reel-to-reel tape machine) installed in the living room. Unfortunately, as toddler I “posted” a lot of his 7” vinyl through the slots in the floorboards – including a few rare beat records, I’m sure! His big favourite was Buddy Holly, and if I had to name a song as my earliest memory, it would be ‘Peggy Sue’ played at excruciatingly loud volume, to my infant ears at least.

When did you learn to play music and what was your first instrument? How did you acquire it? What was your inspiration to play? What was the first song you learned to play?

From the age of ten to eighteen I attended a boarding school in Letchworth, about forty miles north of London. Great place to go to come of age as it was co-educational and pretty progressive. I took piano lessons for a couple of years there, as we had a piano at home, but it was my friendship with other nascent music fans that really spurred me to start playing music – as well as the advent of punk rock. Even before then, after graduating thorough glam – Sparks, Slade and Roxy Music were my favourites – I really focused on 1950s and 1960s rock, and tried to hear and find out everything I could, because it all just sounded so fantastic. My early efforts on the piano were trying to master boogie-woogie or things like ‘At The Hop’, enthusiasm trumping technique, for sure.

“My musical education came from a chap at school who in 1977 played me Nuggets.”

What was the local scene like where you grew up? Were you involved in or influenced by it?

Well, at school there were lots of older kids who looked down at us youngsters and listened to progressive rock like Pink Floyd, Yes and Genesis in the dormitories while furtively smoking cigarettes. In fact I still can’t stomach much of those group’s later catalogues because of that experience, although of course Syd-era Floyd is mandatory, early Yes is OK, and I do maintain a soft spot for the first Genesis album, the one that sounds like the Zombies. The guys above me in school were condescending about my interest in 50s rock’n’roll or the Monkees, but when punk came along, the tide turned and me and my friends could laugh at them, as “their” music was suddenly yesterday. My closest pals however were all really turning onto rockabilly and doo-wop, and I shared their interests equally, along with contemporary things like the Jam, Stranglers, Clash etc. However the most influential thing in my musical education came from a chap at school who in 1977 played me Nuggets. I borrowed the record and wore it out – this was the greatest music of all time, with the exciting frisson of psychedelia and 60s experiment, but with as much of the energy I was hearing in new wave.

What was your first band? How old were you? What type of music did you play? Did you play original or cover material? Did you play any gigs?

At school, from 1977 on I played in a succession of groups: piano, drums, and finally bass, using borrowed instruments, as I could barely afford to even buy records in those days. The most significant of these was called the Bourgeois Cliches (after a line of Ringo’s in A Hard Days Night). We did ‘Dirty Water,’ ‘Gloria,’ ‘Hey Joe’ and other garage-type stuff – unusual stuff for teenagers in suburban England of the time (1980), but then Nuggets really had struck a chord. When I left school the next year, my school friends and I formed the Sting-Rays, which was an amalgam of our mutual love for rockabilly and 60s punk. I was 18, the others were a year or two older than me, and what we lacked in technique, we made up for in enthusiasm and a tremendous amount of energy in live performance, fuelled I might add purely by our love of the music and the desire to match the mayhem we heard in the wildest rockabilly and garage records. Right from our first rehearsals we were doing covers of the Elevators, Remains, Doors, Peanut Butter Conspiracy and others, as well as more obscure things we gleaned from Pebbles and the like – ‘I Want My Woman,’ ‘Blue Girl,’ ‘How Much More.’ Our own songs, at least the ones I wrote, had additional, perhaps more diverse influences, from Gene Clark or Love to Wire and the Buzzcocks. We also hated dumbed-down, novelty lyrics: we had to sing about something. The Sting-Rays were together for five years, and underwent a few line-up changes – I played drums for the first few years (standing up, Moe Tucker style) before moving to guitar. We toured the UK and Europe several times, opened for the Cramps, Pretenders and Bay City Rollers (seriously!), and shared the stage on countless occasions with the only like-minded groups in the UK at the time, the Milkshakes and Prisoners. We made a bunch of singles and EPs and five albums, and there is a distinct progression audible on our records when I listen today – as time went on, my love of 60s folk-rock really started to move the songwriting away from the more raucous garage/rockabilly stuff. Recently, someone told me the Sting-Rays “were either loved or loathed”, which I take as a backhanded compliment, because we certainly marched to the sound of our own drum. We were never enough of one “thing” – garage, rockabilly, punk or whatever – to please the crowds in the usual manner, so most of our fans tended to be broadminded outsiders like us.

When and why did you relocate to the US?

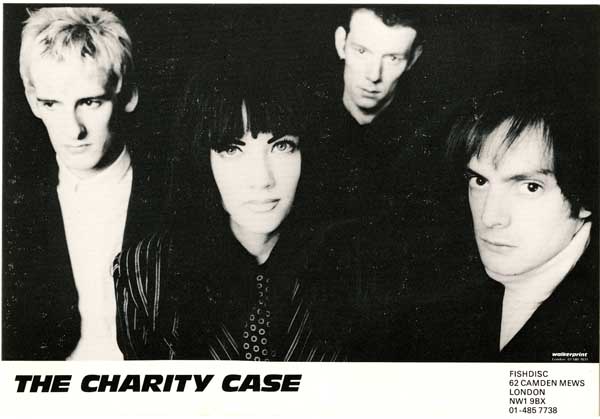

Just before the Sting-Rays split in 1987, I had realised my long-held dream of visiting the US, spending several weeks in California with friends that I had met in London over the previous years. Thanks to the music, I was already primed to fall in love with San Francisco, but it was after that trek that I firmly resolved to move to the Bay Area. Even discounting the music, everything about America just seemed more colourful and larger than life. Having graduated from the University of London, I was selling records on a market stall in Camden Town with not much else going on. I had formed another, all-original, band with a couple of the guys from the Sting-Rays, the Charity Case. We played around and made a 7” single, but the pull of the West Coast was too strong. Also, my girlfriend of the time really wanted to move with me, and that was the extra push needed. I arrived on American shores in October of 1988.

“My heroes were people like the Watchband, Beau Brummels, Oxford Circle, Frumious Bandersnatch”

In 1990 you co-published Cream Puff War magazine to chronicle the musical history of the Bay Area. Would you tell us a bit about the publication? How many issues have been published? When was the latest edition? Will the magazine ever appear again?

The minute I got my feet on the ground, I decided I wanted to find out everything I could about the Bay Area 60s sound. I already knew a lot from collecting records and mags like Who Put The Bomp, but I was curious to meet some of the movers and shakers of the vintage scene. Of course, my heroes were people like the Watchband, Beau Brummels, Oxford Circle, Frumious Bandersnatch and the like, so initially I got a very condescending attitude from the older folks I talked to, who just couldn’t understand why I cared about such obscurities instead of the Dead, Eddie Money or Journey. I ran into Jud Cost who was a fan of the Sneetches, the band I had joined after moving to the Bay Area, and we decided to collaborate on a magazine dedicated to the more esoteric yet no less worthy highways and byways of Bay Area 60s rock’n roll. The first interview subjects were easy – the Great! Society and Mystery Trend had long been on my radar, and of course Shake Some Action-era Groovies was something that loomed very large in my musical upbringing. It was thrill to become friends, and later play with, Cyril Jordan from the Groovies, and the reaction to the mag was very positive. We did a second issue in 1993 that was a lot more in-depth, with features on the Charlatans, Watchband and others.

Apart from a reprint of CPW #1, that has been it. I had designed the whole thing on an early Mac and realized for my part that while it was fun to do this, the fanzine format was a little limiting for what I really wanted to do – create records. Unlike mags like Ugly Things, we didn’t include any advertising, which is what is required to keep a publication solvent.

How did you become involved with Ace Records, UK? What was your position with the label? What was the first project you were involved with?

The Sting-Rays released several records on Ace’s Big Beat subsidiary, and we knew of co-founder Ted Carroll as we used to frequent his fondly-remembered vinyl emporium, Rock On. We used to hang around the labels offices in Kentish Town, using the photocopier to make gig fliers and stealing the biscuits (ie cookies). However, by getting to know everybody there, Ted and Roger Armstrong got an inkling of my love of 60s rock, and so I helped advise on a couple of Big Beat releases including the Chocolate Watchband’s 44 compilation. A little later, my first compilations (circa 1985) were from Major Bill Smith’s Texas stash, including an album of Larry & The Blue Notes. Even though I had moved to the US, I kept in touch with Roger in particular, and after he saw a copy of Cream Puff War, he suggested I look into the possibility of reissuing material by the musicians I had been in touch with.

Your Nuggets From The Golden State series, released on Ace’s Big Beat Records imprint is one of the most respected series of garage/psych music releases by single as well as various artists. What was the inspiration for this incredible series?

As mentioned above, Cream Puff War had been a great initial outlet for my passion for the Bay Area scene, but I have always felt it a duty to turn people on to the riches that populate popular music’s past. With both issues of CPW, we included a flexidisc with unreleased tracks by the artists featured within, which went down very well. I always made a point of inquiring after unreleased material with my various interview subjects and as well as scouring the record stores and swap meets with a vengeance, I also made friends with some local collectors, and acquired a lot of knowledge that way. So when Roger from Ace offered to bankroll a series of compilation CDs, I dug right in, and right away brainstormed a dozen or so volumes, just on what I knew existed.

When and what was the first release in this series? How many volumes have been issued to date? How did you locate the bands and decide which merited release? What are some memorable experiences related to the series?

The initial releases were a bunch of Autumn Records related stuff, the first being the Beau Brummels’ Autumn Of Their Years set in 1994, and the first time a lot of their outtakes had been issued. Going through the Autumn tapes was my first major foray into a tape vault. Immediately after this I did a bunch of work based on the catalogue of Leo Kulka’s Golden State Recorders. I have already been fascinated by recording technology and I soon realised that vintage studios (or the owners thereof) was where I might find the gold, along with label owners or producers. I love musicians, but they are rarely the best custodians of their own work! So there were packages based around local labels like Fantasy / Scorpio and Hush, or studios like Bill Rase’s Sacramento operation. I had some thematic ones in mind too, like The Berkeley EPs collection, that drew together some of the rarest releases of the era. And there were several single artists packages intended from the start, the most significant was the first official issue of the original Charlatans. Subsequent volumes I am also exceptionally proud of are those by the Oxford Circle, Kak, Frumious Bandersnatch, She, Ace Of Cups and more recently, the Stained Glass.

It’s been a while since I counted the specific amount of volumes under the Nuggets From The Golden State banner, and some have been deleted, but to date I think it totals about thirty discs. The criteria for anything I do is based around historical significance, musical quality and rarity. I relish the challenge of officially issuing material rumoured to exist or only available upon horrible-sounding bootlegs, like the Charlatans, or creating “new” albums that shine a light on a neglected artist, or neglected era of an artists career. Such was the case with the Sons Of Champlin’ Fat City, which is comprised of an unreleased album recorded in 1966-67 for Frank Werber’s Trident Productions. Getting to know Frank, an amazing cat who had turned three frat boys into the biggest sensation of the late 1950s (the Kingston Trio), was amongst the highlights of my tape sleuthing career. He was out of the biz and domiciled in the wilds of New Mexico, but after some gentle romancing, Frank invited me down to check out what he might still have and it turned out to be an embarrassment of riches, all stowed in the vault of an old post office. So much good stuff – the Sons, Mystery Trend, Blackburn & Snow, We Five plus a lot of client tapes from his studio including Grateful Dead, Sly Stone and Quicksilver items to name just a few.

You have been nominated for Grammy awards for Best Liner Notes on more than one occasion. What releases did these liner notes come from? But you are known for writing more than liner notes. What are some of the publications you have written for and what are some of the topics you have written about?

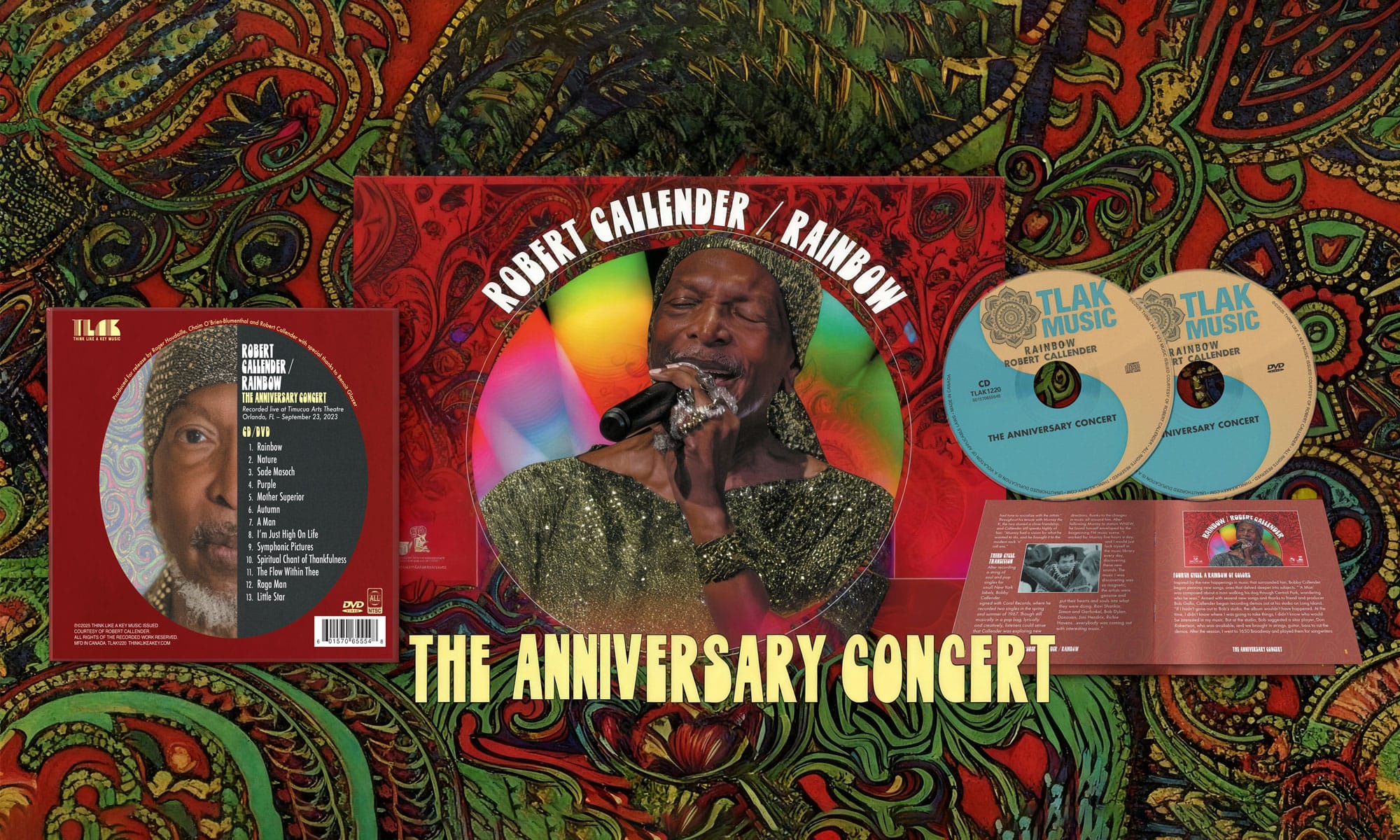

The Best Album Notes nominations I have received were in 2011 for in The Music City Story, a box set of R&B and soul from a Berkeley label that was another holy grail I managed to luck into (funnily enough, amongst a thousand reels of doo-wop and funk I discovered a rare demo session by Big Brother & The Holding Company, of all people). In 2013 the nomination was for the notes for my reissue of Country Joe & The Fish’s Electric Music For The Mind And Body, which was a pleasant surprise as the Grammys doesn’t recognize psychedelic music very often. And 2014 was for the notes to I’m Just Like You: Sly’s Stone Flower 1969-70, a compilation of Sly Stone related productions I assembled with the help of the great man himself – now that’s a story!

Outside of Cream Puff War and the occasional few paras for books that collate work by various different writers, in truth I haven’t done much writing outside of liner notes. Occasionally I have done articles for Ugly Things or the like but to be honest I’d prefer to be off in search of another tape vault. Rather than be a commentator, I like to be the person whose work gets commented on.

Your work on the Zombies catalog is renowned and the 1997 box set Zombie Heaven is still one of the benchmarks by which individual artist box sets are judged. What was the genesis of this project? Would you describe the process you followed in compiling and releasing the 4 CD, 119 track collection?

The Zombies set came about because Ace happened to have a good relationship with the owners of the Zombies’ catalogue, a music publisher who handles a lot of jazz copyrights. A causal conversation with Roger from Ace about this got me thinking, and when I proposed an all-encompassing box set, rather than baulk as most other labels would, he told me “go ahead.” Being a major Zombies fan, I had already mapped out the basics of the set, aiming to at least get the correct mixes in place. What Zombies masters were available in the CD era tended to be very poor, 70s era remixes and phony stereo that did not match the quality of their original mono singles. I also knew that judging from the stray tracks and anomalies within their discography, some in-depth research was required. So we focused on session reels, acetates, demo tapes and any other places where there might be more Zombies music, and I was stunned, not only by how much stuff I found, but also the unerring quality of everything, even the roughest home tapes or radio appearances. More importantly, the guys in the band, to a man, were some of the sweetest and most supportive artists I have ever worked with; no egos, and a genuine enthusiasm for my enthusiasm for them. Everything fell together perfectly, and even today when I think about Zombie Heaven, I realize that the Zombies are one of only a few acts in the history of popular music whereby you could squeeze their entire works into a set and yet have it remain a satisfying listening experience from start to finish.

Since 1998 you have been involved in the Rhino Records’ Nuggets box set series. How did you come to be involved? What was your role in expanding Lenny Kaye’s original 2 LP set Nuggets into the 4 CD box set Nuggets: Artyfacts From The First Psychedelic Era 1965-1968? What was your favorite part of working on this box set? Would you share a couple of your favorite tracks?

It’s a interesting story. Even before I embarked upon compiling the Nuggets From The Golden State series for Big Beat, I was friendly with some people who worked at Rhino like Bill Inglot, who helped facilitate accessing certain catalogues like Autumn. But I got involved with the Nuggets box because while working mail-order, selling records and CDs, a frequent customer was Gary Stewart, then the VP of A&R at Rhino, and so he became aware of what I had been doing for Ace and my intense interest in 60s garage and psych. Gary was the one who produced the Nuggets box and suggested basing it on the original album, with the best of the genre spread across the other discs. He asked me what I thought should be included, and then enquired, do you know anyone that can write? I pitched myself in an honest fashion, and therefore got to contribute an essay about the global influence of the original Nuggets, as well as providing a lot of hard factual info for the track notes.

You have been a part of several other parts of the Nuggets box set series. Which projects have you been involved in and what role did you play? Would you share some recollections from your involvement with the series? Do you have a favorite among the Nuggets releases?

After the first Nuggets box came out, the response was extremely strong, and I soon heard from Gary that he intended its sequel to be vintage “nuggets” from around the world. There was a group of collectors and aficionados that he tapped to suggest items for inclusion, and in fact at one point we had a meeting at Gary’s house in LA with myself, Mike Stax, Bill Inglot and a bunch of other knowledgeable folks that felt like a rock’n’roll version of the movie Twelve Angry Men, with everyone lobbying for their favourites. I would say that quite a few titles on there are down to me – the Mockingbirds, We All Together, the Mascots. More importantly, Gary felt I had contributed enough to the set in all areas – writing, licensing info, hard data etc – that I should get co-production credit for Nuggets II. Sacriligeous maybe, but I think in some ways it’s almost a more enjoyable listen that the first Nuggets set. The subsequent Children Of Nuggets set, of 80s-90s era revival bands, was not something I would have dreamed up by myself, but when asked, I was happy to help assemble it.

On the other hand, the Love Is The Song We Sing overview of the Bay Area 60s scene that I put together in 2007 was never intended to be a Nuggets volume – after all with the inclusion of things like ‘White Rabbit,’ it would hardly constitute a bunch of garage rarities. However once they agreed to do it, Rhino felt they needed to add the sub-title San Francisco Nuggets 1965-1970 to help market it, which I was fine with, as after all this was in the fortieth anniversary year of the Summer of Love, and record labels like Rhino always need an angle. As to that box, I am inordinately proud of it, as unlike the other Nuggets boxes for Rhino, it was essentially my vision throughout, though Hugh Brown the art director really helped make it look so handsome. That Love Is The Song We Sing subsequently received a nomination in the Best Historical category at the Grammys really meant a lot, because of this. The ensuing Where The Action Is: Los Angeles Nuggets 1965-1968 box was suggested by Rhino because of the reaction to the SF set. I was happy to be intimately involved – and receive another nod in the Best Historical category – but it was not 100% my baby.

(I might add that Grammy nods are very nice, largely because you are being judged by your peers in the industry, but really, I am not hung up on credentials. I get as much juice from an complimentary e-mail or someone telling me “I really liked that comp you did,” as I do from any “official” recognition).

How do you normally become involved in a musical project? Do they usually begin with an idea you have? What is the typical process of turning an idea into a release? Would you share some stories of how you became involved in particular projects? How long does a project normally take?

There can be a lot of ways that a reissue project or a compilation gestates. In the early days of doing things for Ace, I would brainstorm compilation ideas based on what I knew about labels, artists, or other factors related to a historical scene. The San Francisco Bay Area was an easy subject of course, because it had a resonance in the larger music scene as a whole, but also there were plenty of easy-to-access sources of repertoire. If you have an idea, the next thing to do is to assess how easy it might be to assemble, given who controls the masters. Often this will be the first stumbling block, if they are unknown or prove unwilling to license (hence the proliferation of bootlegs in the garage/psych market). The next important point is the material ie are there tapes, what is the quality, and how can I get at them. Is the artist, producer, label owner or any other interested party around to contribute information and visuals to the package? It is rare that all three of these aspects fall together seamlessly, but it does happen.

I should mention that I am probably unusual in the back catalogue / reissue world in that, with certain exceptions, I handle every aspect of a release I work on. This entails: coming up with the idea; figuring out who owns it and working out a deal on behalf of Ace or whichever label it might be for; transferring the tapes and editing/mixing them where necessary, interviewing the participants and writing the liner notes; scanning the pictures and other visuals; providing text audio and visuals to the label and then overseeing the design and final mastering. I can’t think of anyone else who does to this to extent I do, though most reissue types would find some of the processes tedious. But by overseeing every step of a reissue along the way, I can stay in control of it and more or less keep it in line with what I had originally intended. I can also then speak with absolute authority about how a particular record or set of recordings was made, having manhandled the nuts and bolts myself. A happy by-product of doing my own tape transfers is that I can often “compile out of the vault,” as Ace likes to call it. In other words, you might come across some strong stuff while looking for something else or just doing a methodical tape trawl, and all of a sudden a project presents itself. Such a case is the Dan Hicks’ Early Muses comp, a demo album I found amongst the Trident tapes that is pure vintage Hicks, recorded while he was still with the Charlatans. As I knew Dan and he was agreeable, that was a fairly easy collection to get out there.

Conversely, a project that took many years to come to fruition was the release of the Rationals’ great mid-60s sides for A-Square. I first spoke to Jeep Holland, owner of the masters in 1997, and while he admitted he had been harassed by other reissue labels for the A-Square stuff, it turned out that he was a fan of Ace Records and therefore willing to listen to my proposal for both Rationals and a various A-Square collection. Sadly he died shortly after, and the materials went into limbo for several years. His brother Frank took over the estate and eventually I was able to meet with him in person in New Hampshire to reiterate my interest in reissuing his late brothers productions. I had an opportunity to look over what tapes there were, and then on a subsequent visit got to copy the masters. All this took about a decade to accomplish, and while Frank Holland was amenable to letting us use what he had, several of the Rationals’ Cameo-Parkway masters were now owned by ABKCO ie Allen Klein’s organization, who were notoriously difficult to license from. It took another couple of years of legal to’ing and fro’ing before we finally got those cleared. I’m sure Scott Morgan was doubting I would be able to pull it off, as he and I had been in discussion about the Rationals even before I had reached out to Jeep. Thankfully he is a trusting and patient fellow, and Think Rational is one of the most pleasurable comps I have worked on. Plus Ace now owns the A-Square masters, so the guys will get paid – all’s well that ends well.

The past couple of years has seen the realization of the reissue campaign of Sky Saxon and The Seeds with five titles released between 2012 and 2014. What was the inspiration for the reissues? When searching the tape vaults how do you decide which takes to include? How did this project compare to your experience working with The Zombies catalog? What were the highlights of The Seeds’ reissue campaign?

It seemed to me that the Seeds were the last of the iconic garage outfits to be in need of an overhaul of their catalogue – and a reappraisal of their unique place in the rock n roll firmament. Like most children of punk rock, Seeds records always struck a chord with me because I could relate to the intensity and power of the minimalist approach. Ace had a good working relationship with GNP Crescendo, owners of their catalogue, who are still very active as a record company, so I explained my ideas to Neil Norman, son of founder Gene Norman, who had taken over the running of the label. I suggested revamped versions of each album with remastered sound, along with whatever bonus tracks we could find to include. He liked the idea but was hesitant to let me get into the tape vault at first – yet I won him over and we are both glad we did, as the session tapes threw up some really great stuff that Neil admitted he was not aware of. The Seeds were prolific in the studio, often recording a title on three or four different occasions, and it was fascinating to discover Sky sang live on almost every take, and he was always “on” – so there was a lot to choose from. We located the original mono masters that had not been used since they were first issued – and which sounded a lot more powerful, especially on the earliest sessions – plus unreleased tunes, and also the Raw & Alive album without the overdubbed screams. I had an inkling we would come across some of these things, but I was still surprised at the quantity of material to go through, so in that manner, it did bear a resemblance to the thrill I had gotten with the Zombies tapes. Hearing the Seeds at work in the studio, without Sky’s eccentric overdubs and flower-power gibberish, really affirmed my understanding of them as a crack rock’n’roll band. One highlight was the incredible fifteen minute long full take of ‘Evil Hoodoo,’ where they do not let up from start to finish.

When did the idea of a film about The Seeds come to you? How long did you work on Pushin’ Too Hard and what was your role in the movie’s production? Would you describe some of the challenges to finishing the film and how you overcame them? How involved were the members of the band? The film received a very warm response to its limited screenings. Are there plans for further theatrical or DVD release of the film?

It took about seven years from the start of filming to the theatrical premiere last summer (2014), but luckily the work on the movie dovetailed with the reissue series and in fact both processes threw up things that benefited each other. Neil Norman already knew that he wanted to make a movie about the Seeds – he’d directed other documentaries on GNP Crescendo artists like Rusty Warren. However I think when he saw my enthusiasm for the Seeds and my understanding of their importance – plus a certain objectivity, given that I was not the record label that owned their material – it spurred him to put it into motion, and thus I became the producer / writer / principal researcher etc. The main challenge we had was finding vintage footage – there’s quite a bit that exists, but it tends to be of the same couple of tunes. There were also some interview requests that were turned down – Neil Young, Ray Manzarek – but I think who we do have talking in the movie adds a certain amount of eloquence you might not expect. Iggy was particularly good on explaining the importance of the Seeds, and Bruce Johnston of the Beach Boys, the Bangles, Johnny Echols of Love and others all weigh in very well. I did meet with Sky – he was on board with the project and in fact I was getting ready to fly out to Austin to interview him when he passed. And while I went to Michigan to film Rick Andridge, he was already in an advanced state of dementia so we could only get some shots of him playing drums – very sad. Rick’s voice is on the soundtrack though, thanks to the good graces of my friend Jeff Jarema, who provided the audio of a phone interview he did back in the 90s. As to Daryl Hooper and Jan Savage, they have been just fabulous, with Daryl’s collection providing a large part of the visuals that you see in both the movie and the reissue CD booklets. Currently we are still showing the movie at theatres across the country, and plan to take it to the UK in the spring on 2016. So a blu-ray or DVD will probably not happen for some time. There will however be a soundtrack CD coming soon, which includes more unreleased Seeds gems.

Big Beat Records is certainly not the only label you have worked for. What are some of the projects you have worked on for other labels? Do you have any idea how many releases you have been involved in over the years? The number of credits listed for you on AllMusic.com is simply mind boggling. Do you have time for any hobbies outside of music?

To answer your last question first: not too much! Music is an all-consuming passion, and as Sly once told me, “you can take drugs away from me, but don’t take music, ‘cuz then I’ll die.” But I like to hang out with my wife, go out to eat, or stay home and watch old movies and TV shows. Plus I read a fair amount, and keep up on the news. I have probably been involved with a few hundred releases over the past two decades, but the ones I really count are those that I have completely supervised (compilation, audio, liner notes etc). I would say that the list of those is probably getting up to well over a hundred at this point. Ace / Big Beat is the main resting place for these projects and my loyalty fully lies with them, as it should, because first and foremost they give me an autonomy that I don’t think anybody else would be willing to. Most other labels I have been involved always have someone looking over your shoulder. In the US however, Light In The Attic are the closest to Ace because of their commitment to quality, and they have a great marketing / distribution set-up which is so important in this age of diminishing sales, particularly for back catalogue. The Sly Stone package (referenced above) I did for them was a lot of fun, and no other label outside of Big Beat would have let me do the recent Kitchen Cinq anthology in the way LITA did. Rhino is more or less defunct as far as physical is concerned, but there are some other hip US labels I have done stuff for, like Omnivore (for whom I have produced packages on Darondo, Alex Chilton and Ron Nagle).

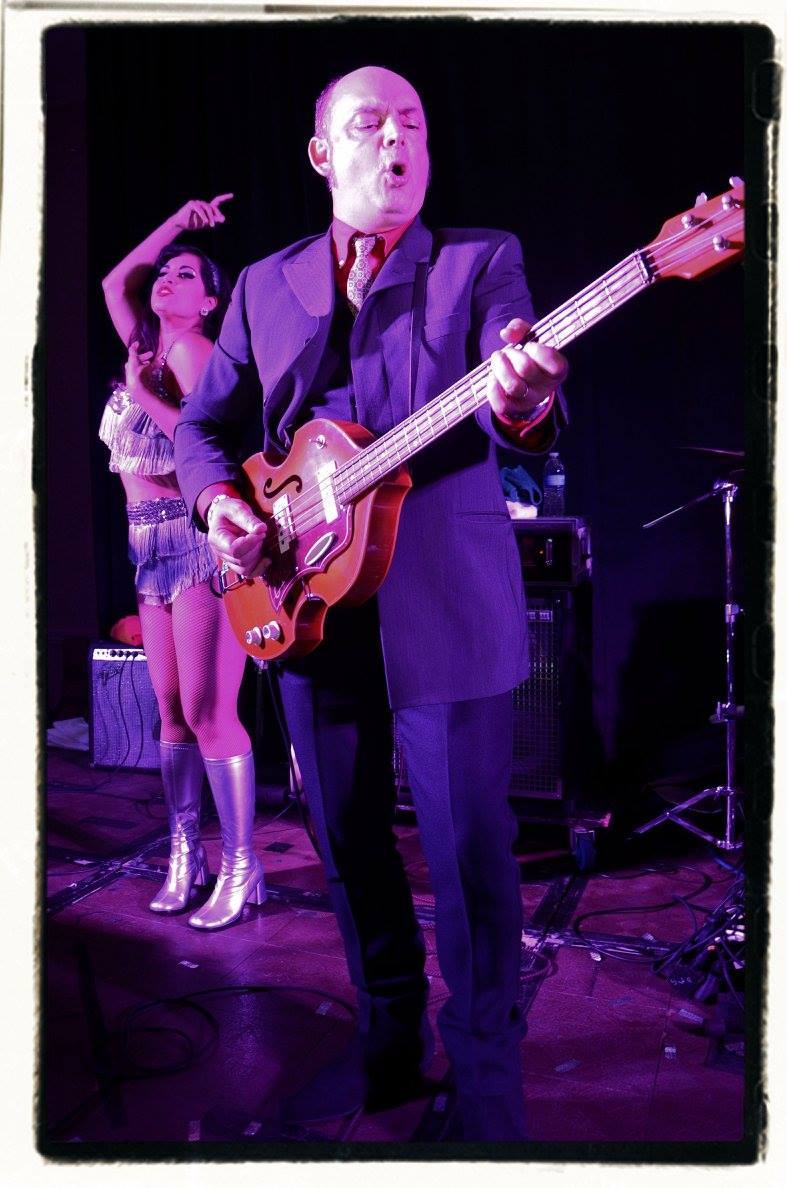

You have been spotted playing on stage with such bands as The Chocolate Watchband and the Beau Brummels. How did you manage this? Would you describe the experiences? Is there anyone else you have appeared live with that our readers may be familiar with?

Yes, I am a groupie – not only do I reissue them, I play with them! I used to joke this was the ultimate in “archive research” that you could do on an artist. Seriously though, these situations happen organically. I always strive to remain convivial with anyone I work with, and in doing so I have become good friends with many musicians I have admired from afar. So when the opportunity to perform with someone like the Watchband, it’s almost like you are a pal helping out. I have to say, the thrill of performing with Dave Aguilar and company is one that never diminishes. The new augmented line-up with three original Watchband members, Daryl from the Seeds, and yours truly on bass is something that would have been inconceivable to my teenaged self when first listening to Nuggets all those years ago. Similarly, Sal Valentino and the other Brummels are folks I’ve known for a long time and so playing with one or more of them is natural, but nevertheless a high honour. I have also been a Flamin’ Groovie on at least one occasion (and played with Cyril Jordan in the Magic Christian for several years), and backed some other heroes and heroines on stage, such as Kevin Ayers and Sharon Tandy. I’m a current member (on keys and bass) of the Rain Parade, who I’ve worked with in other capacities. Loved their records when I was still living in the UK, so that’s a lot of fun. But perhaps the most significant is the band I also currently work in, Powder, with my dear friend Rich Martin, whose vintage recordings I have helped bring to light back in the 1990s. With the new Powder, I have really gotten back into songwriting and also, as an adjunct, recording. So we are finishing up a new album engineered at my home, and its something that I am exceptionally proud of.

What are some of the reissues you are working on that we should be on the lookout for? Are there any future projects you can give us a heads up about?

There are always many pots cooking on the stove: ones about to come to a boil are a Sonics vinyl box set for Etiquette (another group I am so grateful to be friendly with), plus for Big Beat are Golden State Psychedelia, the latest in the Nuggets From The Golden State series, and Kinked, a compilation of vintage Ray Davies/Kinks songs and sessions. Plus a Paris Sisters anthology, four volumes of 60s soul label Loma, more Zombies on vinyl and an expanded version of the Jim Dickinson cult classic Dixie Fried. The late great Sean Bonniwell of the Music Machine bequeathed his tapes and copyrights to me and a couple of friends – yet another humbling high honour – and so we are planning to continue to celebrate his legacy with from that amazing stash including Sean’s psychedelic soundtrack work. Finally, there a particular set of repertoire on the horizon that I am truly thrilled about, as its something I’ve been daydreaming about since before I came to the US – can’t spill the beans just yet, but I know you and your readers will be into it!

There are hundreds of other things I would love to ask you about, but instead I’d like to ask if there is anything about yourself, your music, upcoming releases or anything else we haven’t discussed that you’d like to tell It’s Psychedelic Baby Magazine readers?

Well people often ask, when are you going to run out of things to reissue, or, if they are less polite, resurrect from the grave. My stock reply is there I would need several lifetimes before I would be done re-presenting – or presenting for the first time – great moments from popular music’s past seventy-odd years. So you won’t be rid of me yet…

Again Alec, thanks so much for taking time from your hectic schedule to give our readers a look inside the music industry from your unique perspective.

– Kevin Rathert

Fans of Alec may be interested to know that his band 'The Charity Case' have their long lost LP 'How To Fall' being released by Trash Wax 28 years after it was recorded. The record is a limited edition of 350 copies with a possible cd release later in the year – due late Feb/early March 2016, available from http://www.trashwax.com

[…] figures in that scene. Initially it was going to be a trio gig (Joe, Alec Palao (see interview here), and myself), and that quickly expanded into a full band that included Matt Piucci from Rain […]

Hope you will be able to do something with my acetate. the Bummers 2020

The Bummers!

Alec, Palao, Heard that you might be producing a movie about Frank Werber. Any truth to that?

Alec may be a friend of mine; however, he is really an awesome bass player–he can sure deliver the killer punch when it’s needed!