Westernized Ecstatic Trance Guitar with Robbie Basho and Peter Walker

As a lifelong music lover whose tastes aren’t driven by what’s popular, I’ve found a lot of treasures in the cut-outs bin, so to speak.

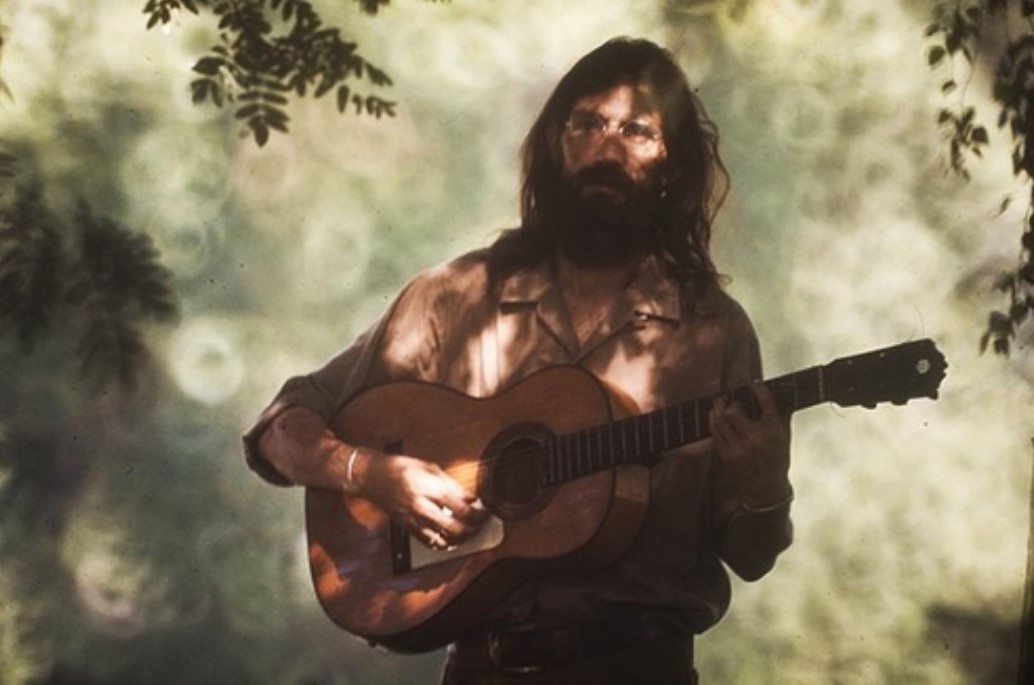

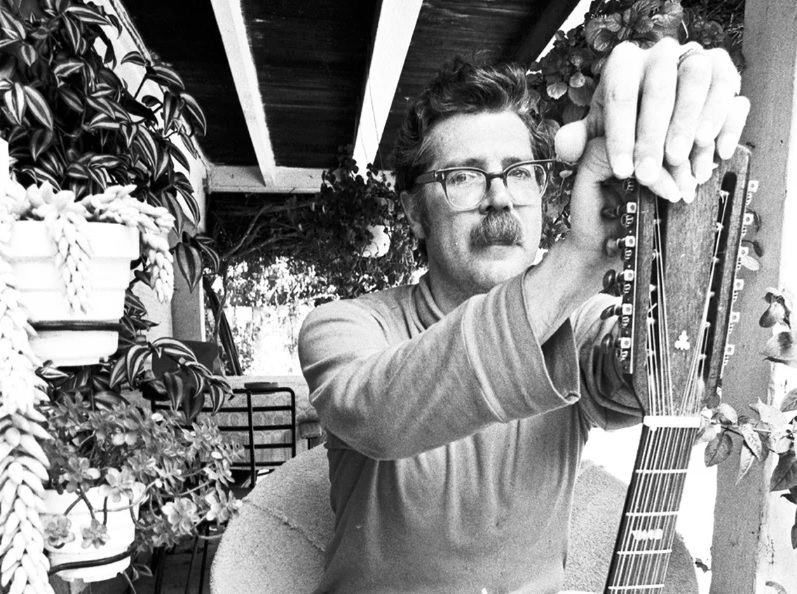

Among the cast-offs overshadowed by the blast-offs, if you know what I mean, Peter Walker and Robbie Basho are proponents of Westernized ecstatic trance music—a form that stood a chance of becoming a dominant force five or six decades back, but which has since become a specialty—two guitar players with as much or as little conscious intent as dervishes dancing on hot coals, who have surrendered their creative selves to the universal spirit. Google those names. It’s a level of impersonalized commitment and devotion shared and displayed by these two artists that’s rarely seen among today’s popular musicians.

Both musicians were followers, to different degrees, of Indian musician Ravi Shankar—Walker also of LSD guru/ CIA advocate Timothy Leary—which is a heady mixture. Albert Einstein named “combinatory play” as the fertile ground begetting the best of solutions.

Walker is an American folk guitarist, born in 1938, known for his skillful performances blending Indian classical and Spanish flamenco traditions. He gained recognition for his recorded work during the late 1960s, becoming a fixture of the Greenwich Village folk scene of the mid-60s, and committing himself to touring and public performance from 1965 onward. Walker’s attendance at a Shankar performance in San Francisco earlier in that decade saw him embrace extended periods of study of raga under both Shankar and Ali Akbar Khan. Through mutual Boston associates, Walker also developed a strong friendship with LSD pioneer Leary, becoming “Musical Director” of his “Psychedelic Celebrations.” In recent years, his reputation has seen a resurgence among younger American and European outsider folk artists, resulting in new opportunities for touring and recording.

Basho was born in Baltimore and orphaned as an infant. Adopted by the Robinson family, Daniel Robinson, Jr. attended Catholic schools in the Archdiocese of Baltimore, going on to prep school and college. His interest in acoustic guitar grew during his college years, as a direct result of friendships with fellow students like Phil Ochs’s cousin, Max Ochs. In 1959, Basho purchased his first guitar, simultaneously immersing himself in Asian art and culture and changing his name to Robbie Basho, in honor of the Japanese poet Matsuo Bashō.

Basho saw the steel-string guitar as a concert instrument, and wanted to create a raga system for America. During a radio interview in 1974, promoting his album Zarthus, Basho described how he had gone through a number of philosophic “periods” relating to music, including Japanese, Hindu, Iranian, and Native American. Zarthus represented the culmination of his “Persian period.” Basho asserted his wish—along with John Fahey and Leo Kottke—to raise the steel-string guitar to the level of a concert instrument, stating that the nylon-string guitar was suitable for “love songs,” but that its steel counterpart spoke the language of “fire.”

Like Peter Walker, who studied with the Indian sitar player (as did George Harrison and countless other aspiring musicians of their time), Robbie Basho became interested in ragas after hearing Ravi Shankar, whom he first encountered in 1962—around the same time as everyone else. During his career, he produced numerous albums, some of which are still available. Basho died unexpectedly at the age of 45 due to an accident during a visit to his chiropractor (!), where an “intentional whiplash” procedure caused blood vessels in his neck to rupture, leading to a fatal stroke.

“I spent years on the road singing these folk songs with no meaning, just emoting these things. Then it dawned on me, music is supposed to say something, to do something. Then I started seeing how high and beautiful I could go,” he said in a 1974 radio interview.

Robbie Basho’s surreal death—likely the result of a pre-existing car accident injury—cut short the trajectory of his musical career, obscuring that he was one of the most inventive Western guitar players of all time, offering a ritual experience rather than a rendition. His music is deeply idiosyncratic, impressionistic, and intensely emotional, strong with an eerie sense of commitment. Beyond that, he was on a genuine quest to integrate and represent non-Western folk and spiritual traditions through the development of esoteric tunings and conceptual roots for his songs—as was Peter Walker.

Upon hearing a Robbie Basho number called “Blue Crystal Fire” in the soundtrack of a movie called Roving Woman, I was immediately struck by the depth of commitment in Basho’s falsetto. Peter Walker, as far as this reporter has been able to discern, is still alive, and it’s said he has never played the same series of notes twice. Can it be? He has released about ten albums, some of which are available on disc. He has also released three books on Amazon so far: Karen Dalton: Songs, Poems, and Writings, a collection of material written by his friend Karen Dalton (another figure from the Village folk scene); Tune Up Drop In, a guitar teaching book; and Road to Marscota, a fictional story of the early sixties.

Zack Kopp