Maqom Soul Records: Yashlik, Uyghur Psych, and the Modal Jazz of the Soviet Underground

Tashkent in the 1970s was far from the quiet cultural outpost many Western listeners imagine.

The city was a lively meeting point where Crimean Tatars, Koreans, Uyghurs, and other communities lived alongside the realities of Soviet cultural policy, creating a unique and often overlooked musical environment.

Maqom Soul Records, a new archival label, is working to document and reintroduce this musical history. Founder Anvar Kalandarov originally focused on collecting global garage and psychedelic records, searching for rare and overlooked releases. His direction changed after discovering a recording by Uzbek singer Nasiba Abdullaeva, which prompted him to begin researching the music of his own region. Today, Maqom Soul functions as both a label and a preservation project, highlighting a period when folk traditions, estrada, jazz, and early synthesizer sounds intersected in unexpected ways.

The label’s debut release is Yashlik, originally recorded in 1978. The album reflects the Soviet VIA (Vocal-Instrumental Ensemble) system, in which many groups were affiliated with factories or state cultural institutions. Despite those constraints, Yashlik developed a distinctive approach. As Kalandarov explains, the group experimented by performing Uyghur musical material using the instrumentation of a rock band, producing a sound that stood apart from many official ensembles of the era.

Because access to Western recordings was limited, musicians often relied on experimentation and adaptation, shaping highly individual styles. Kalandarov located the original master tapes for Yashlik in Almaty, allowing the recordings to be restored and reissued for contemporary listeners.

Maqom Soul’s archival work continues. The label is currently preparing a reissue focused on Uzbek modal jazz fusion, part of an ongoing effort to bring overlooked regional recordings back into circulation.

“What really sets Yashlik apart is that they decided to play Uyghur music using the instruments of a rock band.”

So, let’s get right into the thick of it. Maqom Soul Records feels more like a preservation society. What was the actual catalyst for getting this off the ground? Was there a specific “eureka” moment digging through crates in Tashkent where you thought, “Right, the world needs to hear this, and I’m the one who’s got to sort it”?

Anvar Kalandarov: I’ll start by saying that I’ve always been a huge music fan and a record collector, but at the beginning it was really the music itself that mattered most to me. I’m deeply into garage and psychedelic rock from all over the world, and I’m especially drawn to the sound of Southeast Asia. I love digging up deeply hidden things – you know what I mean? Like some obscure seven-inch by a completely unknown band, that kind of stuff.

Naturally, when you’re into this kind of hobby, sooner or later you start connecting with other diggers and musical archaeologists. At some point, a friend of mine from France asked me to find a seven-inch by Nasiba Abdullaeva, a well-known Uzbek singer. I found it for him, and then I asked myself: what could be so interesting about it? I put the record on, and that was it. From that moment on, I started collecting music from Central Asia as well.

At some point, my wife – she’s a certified psychologist – asked me, “Why are you collecting all of this? What do you need it for?” And that’s when I realized that I wanted to start sharing the music I love. I want as many people as possible to discover this music. I want to give it back to the world.

And why did I start doing this? Because no one else was doing it – and at a certain moment, I realized that I would.

Moving on to Yashlik…it’s a staggering record, really. You’ve got this fascinating collision where the Soviet state-sanctioned “Estrada” sound meets these very traditional Uyghur modal melodies, but then there are these traces of proper psych and jazz creeping in at the edges. How on earth did a group in 1978, with presumably limited access to Western records, manage to cook up a sound that feels that cohesive yet that wild?

‘Yashlik’ is, first and foremost, a band from Kazakhstan, and that’s actually a very interesting aspect of why I fell in love with this record. They managed to create a mix of traditional Uyghur music and rock in a very broad sense. Later on, people like me started attaching labels such as “psychedelic rock” to them, but back then they didn’t even know those terms existed.

As for access to Western records – you’re absolutely right, it was extremely limited. You could only get what was released in a so-called “pirate” way through the Melodiya label, or buy something on the black market. What really sets Yashlik apart is that they decided to play Uyghur music using the instruments of a rock band.

Another interesting detail is that only the second side of the record is in the Uyghur language; on the first side, they sing songs in Kazakh and Russian.

I’m keen to dig into the context of the “VIA”—the Vocal-Instrumental Ensembles. To a Western punter, that term just sounds like “band,” but in the Soviet context, it was a very specific, regulated legal status, wasn’t it? Given that Yashlik was born out of a theatrical setting, how much leeway did they actually have? Was this fusion of sounds a way of sneaking experimentation past the censors, or was the state actually encouraging this sort of “modernised folklore”?

Originally, VIAs were created as a counterbalance to rock bands in their conventional sense. They were meant to carry the ideals of communism and socialism to the masses – to energize and inspire young people. There were a huge number of these VIAs. Beyond the professional state pop ensembles, almost every large enterprise had its own House of Culture and an affiliated VIA.

So, for example, there might be a factory in Tashkent – like the “Maslozhirkombinat,” which produced vegetable oil, margarine, and so on – and attached to that factory would be a VIA that performed at company celebrations and public events. Of course, many VIA members came together because they wanted to play something more Western-oriented, but there were also plenty of purely commercial projects singing songs about the importance of hard work and loving Lenin.Yashlik, however, belonged more to a group of experimental musicians who wanted to enrich Uyghur musical culture by introducing modern instruments.

What was the state of the source material when you found it? Are we talking about dusty master reels rescued from a basement, or did you have to do quite a bit of surgical restoration to get it sounding this warm?

The story of how the idea to release this album came about goes like this. I’d been hunting for a digital copy of this record for a long time, simply to be able to listen to it, but the only thing I could find was a terrible-quality rip on YouTube. The record stayed on my wantlist for several years, but I never came across a copy even in VG+ condition.

Then one Sunday, an older acquaintance of mine called and said he had some records lying around. Coincidentally, my family and I were heading to a country swimming pool in that same direction, so I decided to stop by — without expecting anything at all. I arrive at his place, take a look, and there it is: Yashlik in MINT condition. It was an incredible stroke of luck.

After that, I spent about a year trying to track down the members of the ensemble and their contact details. Then came a trip to Almaty, Kazakhstan, where I met the guitarist. On his computer, I found a copy of the master tape, which he had digitized for the band’s 50th anniversary.

Of course, restoration work was needed after that, as well as proper mastering by a mastering engineer.

It feels like there’s a massive gap in the Western understanding of Central Asian music history. We tend to exoticize it as purely “Silk Road” traditionalism with lots of lutes and silence. But looking back at Tashkent in the 70s and 80s, it seemed to be a proper cosmopolitan hub. Could you paint a picture of what the scene was actually like back then? Was there a genuine underground, or was everything happening in these state concert halls?

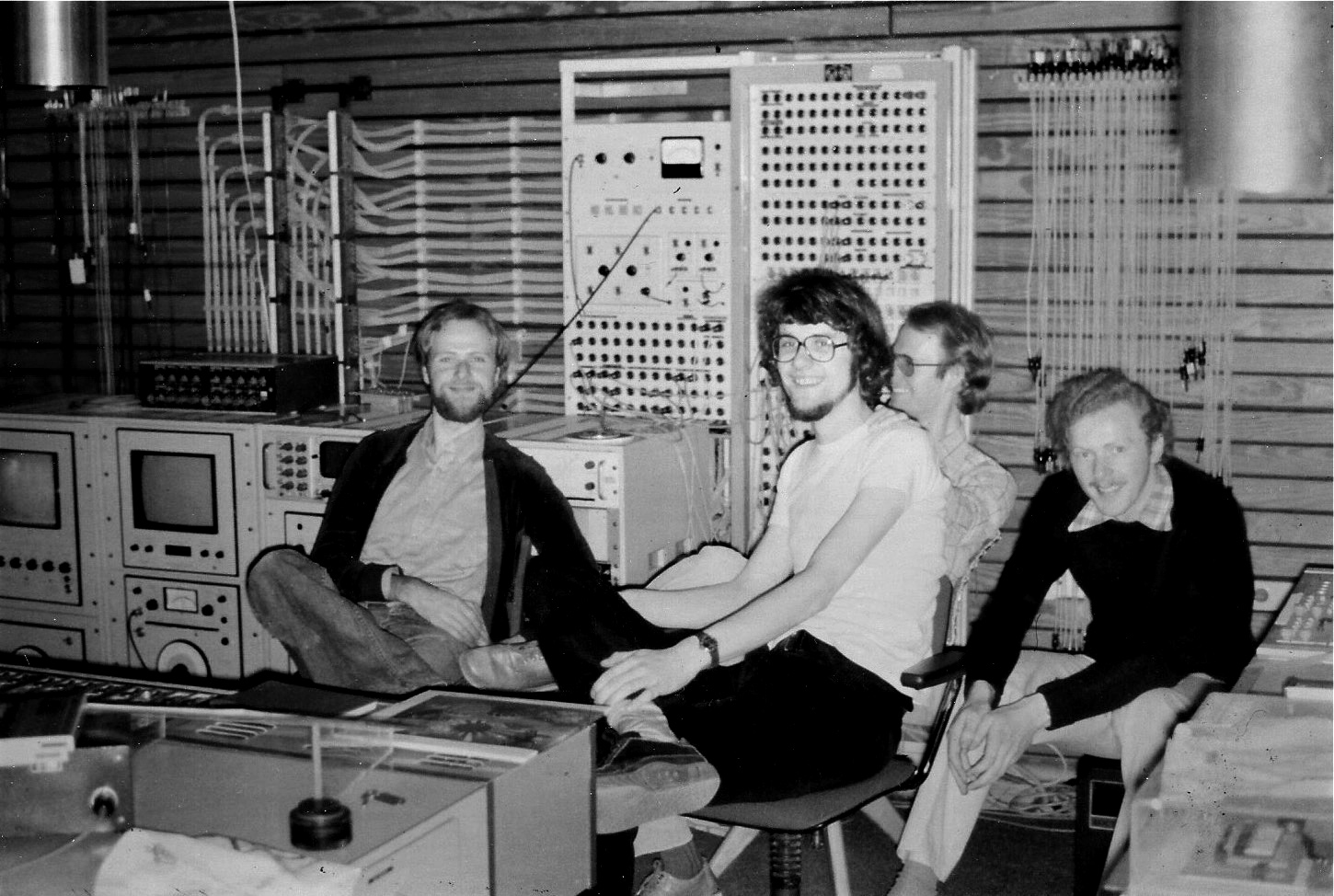

Yes, there absolutely was a scene in Central Asia. On the one hand, it was professional and tied to state-run concert halls, but at the same time there was an entire wave of semi-underground bands playing dances in parks and clubs. What’s especially interesting is that their stylistic approach varied from region to region. For example, in the Fergana Valley there was a strong jazz tradition, so dance events there often featured jazz-influenced orchestras.

If you take a relatively small city – under 100,000 people – at a certain point in time it could easily have 10 to 12 ensembles active at once. Naturally, about half of them were affiliated with factories or state enterprises, while the rest were amateur groups driven purely by creative inspiration. There were solo concerts that drew young audiences, there were park dances – there was plenty of room for all of this to exist.

It’s also important to remember that Tashkent in those years, like Central Asia as a whole, was extremely cosmopolitan. Koreans deported from the Soviet Far East, Crimean Tatars, people from the Caucasus, Greeks, Uyghurs – all of them were resettled there. On top of that, in 1966 a massive earthquake struck Tashkent, and people from all over the USSR poured into the city to help rebuild it.

In the West, this gap exists because no one has really engaged with Central Asian music outside of academic circles. If you dig deep enough, you can find information about traditional music, but not about popular or pop-oriented music.

In the USSR, that steamroller was the State itself. When you listen to this record, do you hear Yashlik fighting against that erasure? Is this record a document of a culture refusing to be flattened?

Yes, absolutely – the Yashlik album is a document of its time, and for me it was only the beginning of my journey. In the late 1970s, there was a slight easing of state control, and several very interesting musical phenomena began to emerge. Within the Korean diaspora, ensembles like Ariran appeared: these musicians wanted to play jazz and jazz-rock, and they managed to do so by framing their experiments within Korean traditional culture. Within the Uyghur diaspora, Yashlik emerged – and there were many similar cases like this.

Unfortunately, or perhaps fortunately, most of this music was written and performed primarily for the Soviet Union, which is why it remains largely unknown elsewhere. Coming back to the label, I can say that from the very beginning I wanted to release and rediscover this music not for the diasporas themselves, but for a Western audience. I wanted – and still want – to find a new audience for such extraordinary musicians as Yashlik.

Just before we wrap up, now that you’ve set the bar this high with Yashlik, where do you go next? Is Maqom Soul going to stay in the 70s folk-rock lane, or are you planning to explore those electronic shifts as well?”

I can’t say exactly where I’ll move next or in which direction, but it will definitely be connected to Central Asia in one way or another. The next release will be a reissue of Uzbek modal fusion jazz.

In general, my interests lie in high-quality music that has unfortunately been forgotten or suppressed.

The electronic sound of the 1990s is fascinating, and it’s probably easier to understand from a commercial point of view, but for me there are still many names from the 1970s and 1980s that haven’t truly been heard yet. So I’ll leave the ’90s for later.

Klemen Breznikar

Maqom Soul Records Instagram / Bandcamp