Interview: Pete Fij Reflects on Mortality, Music, and His New Single ‘Cuckoo’

Pete Fij has released his crystalline, grandiose new track ‘Cuckoo,’ serving as the latest preview of his forthcoming album ‘Up’s The New Down,’ due out this summer via Tip Top Records.

‘Cuckoo’ sees the former Adorable frontman slinging his electric guitar back on and upping the BPMs, blending his fuzzed-up dream-pop roots with fresh elements of electronica. Inspired by his family’s Cold War history and the stylish grit of the spy thriller Atomic Blonde, Fij describes the track’s energy as a getaway car driven by Siouxsie Sioux with The Human League riding shotgun. The lyrics weave a cryptic code of espionage terms, matching the song’s neon-lit atmosphere.

“I wanted to do something more lasting and, perhaps selfishly, more for myself.”

You spent years witnessing people at their most fragile… in care homes and as a Funeral Celebrant. When you’re constantly immersed in the finality of things, does that fundamentally change how you approach creating something new? Was “the reset” a deliberate attempt to literally sing yourself away from the platform of life you were seeing people off from?

Pete Fij: Working with people in the final chapter of their life, as well as taking people’s funerals, really brought home to me that we only have one go at it on Earth, and that you need to try to live your life so that you don’t look back with regrets of what you didn’t do. In the care home where I worked as an Events Coordinator, I sat one evening with a resident who was lying in her bed on end-of-life care. I sang to her one of her favourite songs, ‘Welcome To My World’ by Jim Reeves, and as I did so, she passed away, which was an incredibly moving moment and brought home the reality of mortality and time slipping away.

There were things that I’d put on the back burner for too long, and it felt like it was time to focus on those creative avenues before time drifted away. I’m not sure if the experiences I’ve had have directly squirmed their way into my lyrics (yet), but it’s more my mindset for the need to get on with things before it’s too late.

For so long, your brilliant lyrics were defined by a beautiful, wry melancholy. Now, you’re singing about ‘Love’s Coming Back’ and calling the new album ‘Up’s The New Down’. Honestly, did you have a fear that embracing happiness would somehow dull your artistic edge, or make you less interesting to the fans who connect with your sadness?

In the past, I have written songs that were triumphant and upbeat (Sunshine Smile, Glorious, Breathless…), though it’s true to say that melancholia has been more of a bedfellow in recent times. I did wonder if being more content in life might lead to a dulling of my lyrical opportunities, but you can always count on me to put a little twist in that happiness, and so there will always be showers along with sunshine!

You mentioned ditching the job and slinging the electric guitar back on. What did you realize you were actually missing? Not musically, but personally, when the guitar was put away and the focus was on serving others?

It was the act of creating at the risk of sounding pretentious, “art” (I actually wince as I say the ‘A’ word). My focus at work had been on other people, which was rewarding, and was creative in its own way, but I wanted to do something more lasting and, perhaps selfishly, more for myself.

Why the choice to revive the “fuzzed-up dream-pop” elements now? Was that sound a specific kind of sonic comfort, or did you need that particular level of energy and fuzz to properly communicate the feeling of falling in love again and upping the BPMs of your own life?

Perhaps the Adorable reunion shows in 2019 woke something inside of me. I loved doing the delicate, introspective songs with Terry Bickers, which we compared to the sound of The Velvet Underground jamming with The Everly Brothers at 3 in the morning very quietly so as not to wake the neighbours, but I love distorted guitars and electronics and drums as well, and felt I wanted to steer myself back towards those noisier shores. I thought it would be fun. And I was right!

Adorable’s Against Perfection is forever described as a “lost classic.” Do you ever feel haunted by that phrase? Does it feel like a validation, or does it feel like you are perpetually chasing an imaginary version of success that the album was supposed to deliver?

We wanted Adorable to be as important a band as some of our heroes, but that didn’t play out. At the end of the day, my successes, and perhaps more importantly my failures, have shaped me & made me the person I am today. I’m really, really comfortable with who I am, so I don’t begrudge those disappointments.

When it came out, the LP got a review in the NME describing it as a “flawed classic,” which I was genuinely delighted with. There’s always been a part of me that has been drawn to the underdog and embraced that loser chic, so “lost classic” is a phrase I’m more than happy with. I take solace that The Velvet Underground weren’t very successful in their lifetime… although I suppose they did gather momentum within 20 years of disbanding, so we are behind on that timeline. I’m still waiting!

‘If Against Perfection’ is still being talked about, then that’s an achievement of sorts, and if in the description of it the word ‘classic’ appears, then all the better. It’s a good album that I’m really proud of, but I have made others that, in my opinion, match it stride for stride.

You once described a “musical breakdown” leading to your exile. What did that actually feel like? Was it creative burnout, a failure of the system, or a fundamental confusion about who Pete Fij was without a microphone in his hand? And what’s the simple, non-musical truth you took away from that time?

In the early 2000s, I tried to step away from music entirely and concentrate on other things in my life, but after 2–3 years, I realised I needed that creative output.

I wrote & recorded an LP (a version of ‘Broken Heart Surgery’ that I’d later re-record with Terry Bickers) but didn’t do anything with it for a further 5 years—didn’t perform live, play the recordings to anyone, or take any steps to release it—perhaps because I just needed to get those songs out of my system, or perhaps through a subconscious fear of rejection. It was like I was in paralysis, like an out-of-body experience. I didn’t recognise this Pete, as usually I was so proactive.

The non-musical truth is I need music, and I need people around me.

You’ve had to master two very different forms of public performance: conducting a funeral service and playing a headline gig. At the end of the day, when you step off the stage or away from the lectern, what’s the difference between the man who tells someone else’s life story, and the man who tells his own?

Although two very different roles, they are also linked. They are about telling stories, about connecting with people, and there is a performance aspect to all public speaking. Fewer people cry at my shows than at the funerals I take.

You’ve often been compared to singers like Lou Reed and Lee Hazlewood, voices known for their depth, baritone, and inherent gravitas. As your voice has changed over the decades, do you feel like you are finally growing into that rich baritone, or is it a tool you deliberately wield to give weight to these brighter, poppier songs?

My voice has definitely changed over the years, and I’m comfortable with how it’s evolved. On these new tracks there’s a different timbre to it than previously, where there was more space to wallow in the reverb, but it’s nice to be able to have more urgency and edge, and to play with those aspects.

Against Perfection is a record with undeniable moments of melodic euphoria, yet it arrived in a post-Shoegaze landscape that was quickly shifting… Looking back, what are some of the strongest memories of writing and working on that record?

Our timing was out in that we were too late for Shoegaze (’89–’91) and too early for Britpop (’94–’97), so the album kind of fell through the gap between the two, though arguably there are elements in our music that see it as a bridging album between the two scenes… atmospheric, distorted guitars, but vocals far more present than in shoegazing and with clearer verse–chorus structures that are more aligned to Britpop, and we were closer to the pop sensibilities of Britpop than the slightly attitude-light polite stance that we associated with Shoegaze. As an aside, I have little time for Britpop (with a couple of notable exceptions). In truth, we were more interested in sounding like Bunnymen, New Order, Psychedelic Furs & The Sound, so the sound of 1980 was what we were going for rather than re-capturing 1990.

The album came together quite effortlessly—we had the bulk of the songs written before signing to Creation, so we knew we had the backbone of something we felt was pretty strong. Pat Collier (who had produced House of Love’s debut LP on Creation, which we loved) was a joy to work with—he was very much a father figure to us, guiding us through our first two years. We had started working with him before we signed to Creation, and he gave our manager office space in his studio building, so we were very much at home there. Pat sadly died last year, but I’m glad I managed to tell him how much his support & guidance meant to us before he passed away.

We didn’t really think too much about song structures on our early songs, which is why I think sometimes they sound so fresh. Often the choruses were a bit buried, and the guitar hook becomes the chorus. This isn’t uncommon with a lot of bands… as your musical career continues, people learn about song structures and how to play their instruments ‘properly,’ and it can all go a bit bland & predictable.

Was the album’s title, ‘Against Perfection,’ a sincere fight against the polished Britpop machine waiting in the wings, or was it, ironically, a defence mechanism against the impossible standard of hype being created around you by the NME and the label?

Originally it was going to be called Against Nature, but we found out Fatima Mansions had released an album with that title a couple of years before. We then toyed with calling it Against Creation, but, although Alan McGee green-lighted the idea, we felt that it would be flying too close to the wind—we weren’t popular at the label, and we thought this would be too incendiary, so we went with ‘Against Perfection,’ which I think with hindsight is the best of the three. It’s notable that all three suggestions for the album were “Against” something!

The title nods towards a much bigger picture than just a flicking of the Vs to the music industry. I love things that are flawed and imperfect. George Lazenby is my favourite James Bond—in part because of the whole mythology of the story surrounding his doomed career. I love the cracked voice of Chet Baker. I love the faded tiles and peeling paint from the houses in Porto. I love the mystery of The Sound’s stalled musical career whilst their contemporaries burned bright. Basically, I love things a little fucked up and broken.

When you’re writing songs like ‘Love’s Coming Back’ and talking about this whole “reset,” I wonder: how much of that is you actively talking back to the younger you who wrote those deeply intense, vulnerable songs on Against Perfection? Is the new work a conversation with, or maybe even an escape from, that emotional world you created back then?

I see ‘Love’s Coming Back’ as more of an euphoric response to my more melancholic Bickers & Fij tracks or the po-faced art school loser chic of the second Adorable LP ‘Fake’ or the two albums I made with Polak. It’s a wake-up call to me, as much as to anyone else, to enjoy life—because you don’t know how long you’ve got left.

Klemen Breznikar

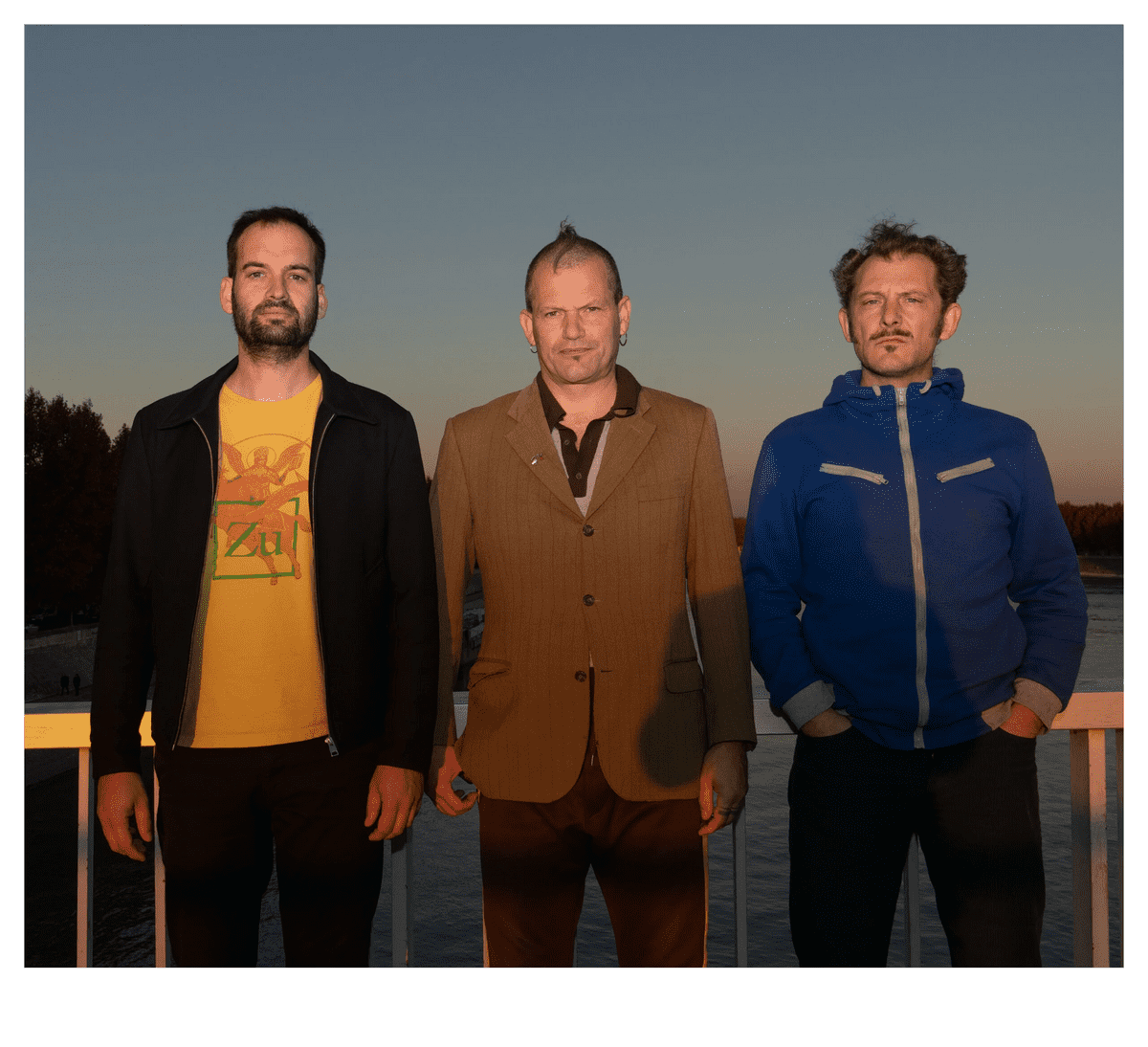

Headline photo: Pete Fij (Credit: Dorian Rogers)

Pete Fij Facebook / Instagram / Bandcamp / YouTube