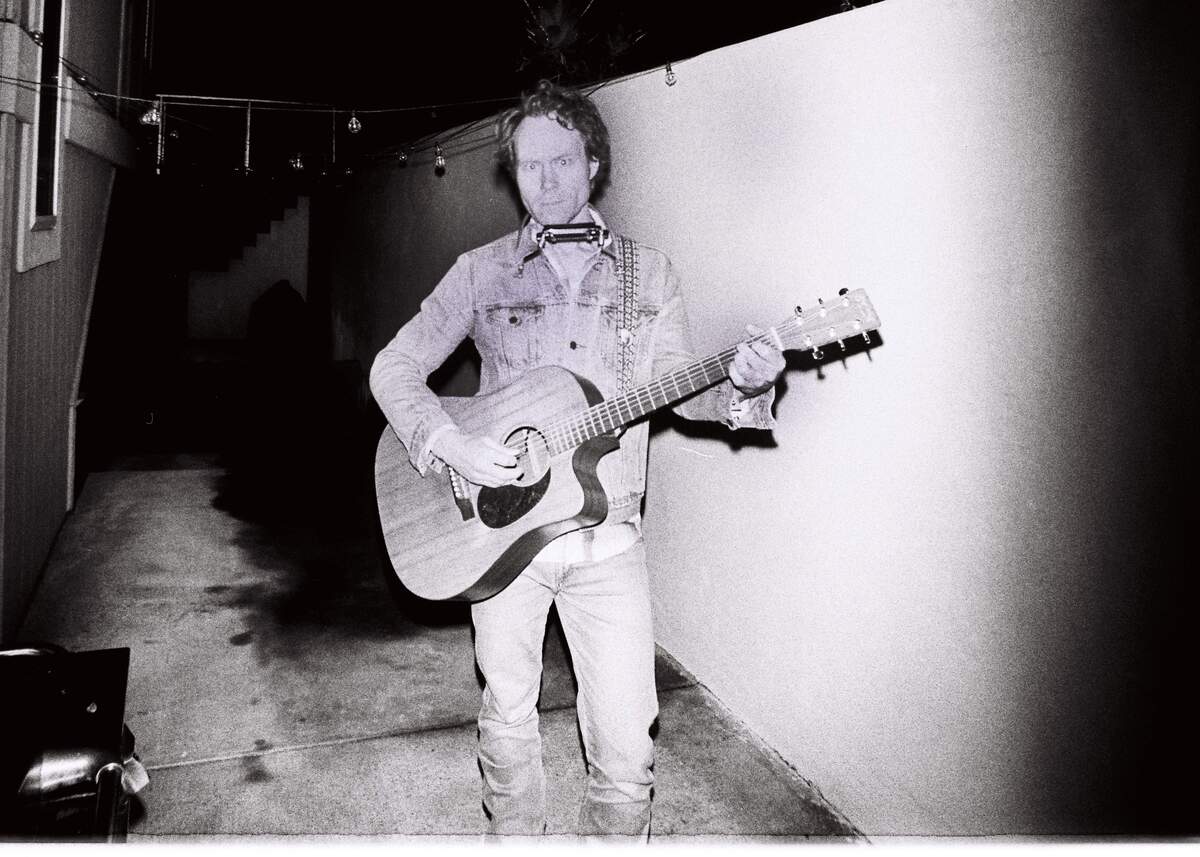

Dennis Hauck Returns to His First Love with Darkly Poetic Americana

Critically acclaimed filmmaker Dennis Hauck, best known for his neo-noir debut Too Late, is returning to his musical roots with a new song that blend cinematic storytelling with Americana.

Once a punk guitarist who set music aside as his directing career flourished, Hauck found his way back to songwriting after the 2021 death of his friend and collaborator, cinematographer Halyna Hutchins.

His latest single, ‘Natural Heart’ backed with ‘Nature of the Beast’ (alternate version), showcases Hauck’s moody, narrative-driven style that evokes Leonard Cohen and Nick Cave. The A-side is a stormy meditation on love and inheritance, while the B-side reimagines an earlier track with stripped-down orchestration and haunting restraint. Recorded live in Nashville with minimal overdubs, the sessions reflect Hauck’s filmic philosophy of capturing a moment’s truth rather than chasing perfection.

Following previous singles ‘Halyna Hutchins’ and ‘Girl from Cedar City,’ Hauck continues to craft songs that unfold like short films, marked by literary flair and dark romance. A limited edition 12-inch vinyl, featuring live bonus tracks hand-numbered by Hauck was also just recently released.

“I don’t find the songs I write to be any more confessional than the films I make.”

Your film, Too Late, was lauded as a “masterwork,” yet it was the immense grief following Halyna Hutchins’ death that reactivated your songwriting. How does a tragedy of that magnitude, which fundamentally altered your life’s creative path, change your understanding of art’s purpose? Is the film you made before a fundamentally different creation than the music you make now, and if so, what’s the chasm between them?

Dennis Hauck: Halyna believed in me as an artist. That meant a lot to me while she was alive. Still means a lot to me now. Writing a song seemed the least way I could give something back to her. There’s a great folk tradition of writing odes to those who have died before their time. But outside of that, I’m not sure I approach creation with any sort of purpose in mind. I like music, so I wrote some songs of my own. I like movies, so I set out to make some.

You inhabit this unique intersection as an artist: a critically acclaimed filmmaker, a seasoned short story writer, and now an emergent musician. Many artists struggle to master one medium. Do you find these worlds complementary or conflicting? More specifically, where does the discipline of cinematic world building end, and the more confessional and immediate intimacy of the songwriter begin?

I don’t find the songs I write to be any more confessional than the films I make. And I don’t view the various mediums so differently. It’s all just words on the page. If it’s a short story or a novel, then I’m done when I get the words to where I like them. Songs and movies involve added steps.

The critics draw lines from your lyrics to Bukowski, Cohen, Dylan, and the Beat writers, a group known for finding poetry in the often dark underbelly of American life. What is it about this specific confluence of grit, romance, and tragedy that you find so essential to your voice, and what contemporary societal darkness are you, in the tradition of those predecessors, attempting to illuminate?

I haven’t made the visit yet, but I’d imagine there’s a dark underbelly to Slovenian life as well. Probably to every corner of the world. I don’t think in terms of American life so much as human life. Anything I’m illuminating is likely to be universal. Primordial. But I wouldn’t use the word illuminate either. Nobody needs me for that. Everybody’s got their own flashlights. But it can provide a jolt when you find someone aiming theirs in the same direction.

The lyrics from ‘Natural Heart’ use vast elements like thunderstorms and wildfires as metaphors for internal, familial drama. The penultimate verse brings the consequences home:

“She’ll grow into a wildfire

There’s nothing to debate about

She’s got a natural heart

That’s the tragic part.”

Is the core of your storytelling a belief in the inescapable, and do you, as the creator of these worlds, ever find a path to grace or redemption for your characters?

I’m no fatalist. I’m too optimistic to think in terms of the inescapable. I always see a way out. My characters might not though.

Your career is defined by pivots: from music to film, and now a powerful return to music. The act of returning suggests that the unwritten songs you couldn’t compose years ago were waiting for the necessary emotional and experiential weight to ripen. Can you articulate what, precisely, was missing in the young punk or indie rock musician’s life that finally allowed the Leonard Cohen-esque poet to emerge?

Urgency, maybe. Making movies takes too long. Covid, the strikes in Hollywood, just the general Herculean task of getting any film project off the ground. You turn around and realize how much time has passed, how much work you’ve done without as much to show for it all as you’d like. Making music is more immediate. But I don’t know whether I could have written these songs years ago. I needed to feel my back against the wall.

The juxtaposition of your singles—for instance, the “starkly elegant” reimagining of ‘Nature of the Beast’ on the B side—suggests you see a piece of art as never truly finished. How does your experience as a filmmaker, who meticulously shapes a final cut, influence the way you approach the reinterpretation and evolution of a song after its initial release? Is this B side an admission that even the first, definitive version is inherently incomplete?

That first version of ‘Nature of the Beast’ is complete and definitive. So is this new one. I give them equal standing. If I could go back to my film Too Late and make it over again, I would not turn down that opportunity. It’s not really about fixing mistakes or making something better. It would be a reflection of where I am now compared to where I was then. Both would be equally valuable, and different viewers might connect to one version more than the other, and either one would be fine by me. But films cost a lot of money to make. It only costs a few extra minutes of studio time to take an old song and try it a new way.

Your film work involved an ensemble, collaboration, and the machinery of a film set. Music, particularly your acoustic touring, is often a more solitary pursuit. How has this shift in process changed your sense…?

Playing solo is often more of a monetary consideration. Sometimes it just doesn’t make financial sense to take a band on the road. There is something to whittling a song down to its barest elements. Certain songs come alive in a different way. But playing with a band is not that much different than collaborating with a film crew. You have a vision, you try your best to communicate it to the people you’re working with, then they bring something of their own to the table that you could never have anticipated. Sometimes you like the original vision better, but it’s stuck in your head. No one can see it. Other times the collaboration is so good you’re happy to forget that first vision.

Considering your deep experience in multiple forms of narrative art, if you were forced to distill your life’s work into a single overarching theme, is it better expressed through the visceral imagery of film, the rhythmic structure of poetry, or the haunting melody of a song?

That’s not for me to decide. I just put this stuff out there and see what sticks.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Dennis Hauck (Credit: Stephen Broussard)

Dennis Hauck Website / Instagram / YouTube