Lost Prog-Rock Tapes from Zeitgeist Emerge After Five Decades

The British progressive rock outfit Zeitgeist, known previously only for their appearance on the fabled 1971 private press compilation K.C.S. Modern Music, has had its complete recorded legacy unearthed.

Lost for over fifty years, the band’s sole session preserved on a single acetate disc cut in January 1972 has now been recovered and restored.

The six-piece ensemble crafted a sound that balanced disciplined complexity with free-form spontaneity. Their output drew clear parallels with the foundational work of Soft Machine and King Crimson, yet possessed a singular and self-assured musical voice. The arrangements feature long, fluid instrumental passages where the textures of electric guitar, saxophone, and radiant flute intertwine with compelling grace.

What the listener encounters is the sound of a young band operating at the vanguard of musical discovery. Their compositions unfold and retreat organically, possessing an intensely lyrical, strange, and vivid quality. Emerging from the collective imagination of a group of gifted schoolmates, Zeitgeist captured a moment of pure, vital discovery.

This recovered material offers a compelling reminder of how the UK’s burgeoning underground music scene often began quietly: a handful of friends gathering in a cold studio, unknowingly committing something truly exceptional to tape. The rediscovery of the Zeitgeist acetate is a significant addition to the history of British progressive music.

“Let’s try and play like all the bands we enjoy listening to and see where that takes us.”

How did the label get in touch and find out about the existence of your material?

Adrian Smith: Jon Groocock of Bright Carvings Records had already been in touch with brothers Adrian and Martin Long, our fellow pupils at King’s College School, whose band Gomrath has an album out on his label. So he tracked down Chas Minall (drummer) and me through them. We knew that Pete Keel (sax/guitar/vocals) had possessed many tapes; he later became our recording engineer. Chas contacted Pete’s widow Val. It turned out that she not only had tapes but also the original acetate of the recordings from the studio.

Before we dive into all the band’s stories, let’s clarify a few details. You originally recorded and released an acetate in 1971 or 1972? Could you confirm the exact recording dates?

The date on the acetate is 31 January 1972.

Who manufactured the acetate, and how many copies were made? Did you send any to record labels?

It is an EMI Emidisc. I think this was the sole copy. The idea was to send tapes out to try and get gigs, but I don’t remember anything being sent to record labels.

Let’s go back to the beginning. Where did you grow up, and what was daily life like for you in your pre-teen years?

I grew up in a place called New Malden, Surrey, on the outskirts of London, and went to school at K.C.S. Wimbledon nearby. My father had been a chorister at Westminster Abbey and was a BBC announcer on Radio 3, or The Third Programme as it was originally, so there was always music at home. Despite his classical upbringing, he was supportive of my interest in rock and jazz, and took a passing interest when I played him works by The Nice, King Crimson or Jethro Tull that had a classical base.

My mother had also worked for the BBC during the war, being a production secretary on Forces’ Favourites. She had a good collection of 78 records, mainly 1940s dance bands.

My pre-teen years were pretty stable, a typical middle-class upbringing with a public school education. My teenage years during the late 1960s were typically rebellious in minor ways, growing one’s hair long and playing guitar in preference to studying.

Was there a particular moment or something that ignited your love for music?

There were many moments: growing up in the 60s with the soundtrack of the Beatles, hearing Paul Tortelier playing Elgar’s ‘Cello Concerto’ from my father’s record collection, hearing the flute playing of Ian Anderson (Jethro Tull) and Raja Ram (Quintessence) that made me realise my flute could be a rock instrument, seeing King Crimson live in 1969 with that wonderful mellotron sound, Mike Ratledge’s great fuzz organ sound and the 7/8 riffs from Soft Machine ‘2,’ going to see Henry Cow many times in the early 70s, and many BBC Promenade Concerts. But perhaps the best thing is that once you have formed a band with like-minded musicians, one is always learning and trading ideas, so that from nowhere, rock or jazz or whatever magically appears and has a life of its own.

Did you have any clubs or hangouts where you and your friends could enjoy the latest music?

There were many clubs, pubs, and theatres around London that we used to go to: The Marquee Club, the 100 Club, the Greyhound, Hammersmith Odeon, the Rainbow Theatre, Ronnie Scott’s.

Could you tell us about the pre-Zeitgeist era? Were any of you in other bands? What clubs did you play, and are there any unreleased recordings from that time?

Before this Zeitgeist line-up, it was just me, Pete Keel, Paul Emmerson and Chas Minall in a band called Gollum, just learning and trying to play covers. No recordings. You can tell what inspired us from an early set list: Amphetamine Annie by Canned Heat, Man of the World by Fleetwood Mac, Manco Capac by Quintessence, ‘The Saga of the Low-down Let-down’ by Sopwith Camel and Serenade to a Cuckoo by Jethro Tull/Roland Kirk.

How did the members of Zeitgeist originally get together?

Pete, Paul and I were all at King’s College School together from the age of about 10. Pete and I got together when we both had guitars at about the age of 12 or 13. We used to listen to new Beatles stuff and try to work out the songs. (We couldn’t!)

When you started the band, did you have a specific idea or concept in mind? For example, “We’re going to take a sound from Soft Machine and do our own version”?

We developed really when Martin joined the band. He was actually a couple of years younger than us but a lot more gifted. Pete started playing saxophone and listening to a lot more jazz. We also took a step forward when Steve joined, just before these recordings, as he also liked jazz/rock – Weather Report, Zappa etc.

I think the only concept really was “let’s try and play like all the bands we enjoy listening to and see where that takes us.” Inevitably, we eventually found our own style, but you could hear where it came from.

What was the songwriting and composing process like for you all?

These early recordings were quite varied, as each of us would submit different ideas. Pete and I would write songs of teenage angst, Martin would provide more polished guitar and sax-based jazzy pieces, and Paul tunes with quirky time signatures. We would all then pile in to try and put a collective sound to it. I think it’s fair to say that at this stage we had little clue as to where it would take us, but this was a time (late 60s and early 70s) of great experimentation.

If you don’t mind, could you go through all the tracks on this new LP and share some further insights?

Side 1

‘Number One’ – I think this was the first piece that Martin wrote for us. The template was: open with a flute theme, let Pete take over with a sax solo while I switch to rhythm guitar, and then Martin would finish with a lovely guitar solo. I think he had just bought a second-hand Cry Baby wah-wah pedal which sounded great.

‘Pipe Dream No. 4’ – Paul wrote this one with some help from Martin. Paul had only been playing bass for about a year, but there’s some fine work from him on these tracks. He was interested in quirky rhythms and odd time signatures. This was the first appearance of Steve playing organ. He had only just joined the band, so is not on all the tracks. Neither Pete nor I were on this track.

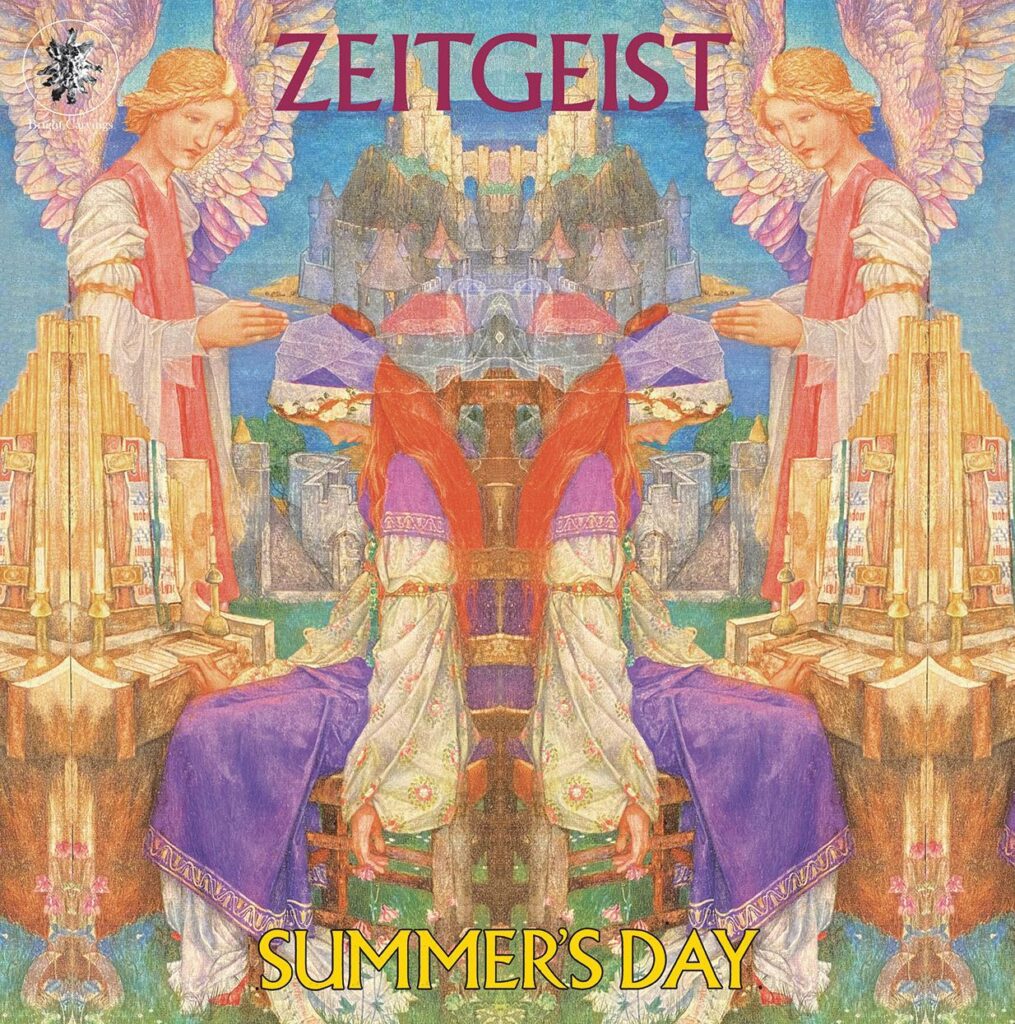

‘Summer’s Day’ – A song by Pete, who sang and took a sax solo. Lyrics somewhat teenage depressive! Chas fancied playing rhythm guitar on this, so I played drums for the first and last time in my life.

‘Pottle Pig Goes t’Supermarket’ – Similar template to Number One. Fine solos from Pete and Martin.

Side 2

‘Surface Tension’ – More magic by Martin with a Fuzz Face distortion pedal. Our first experiment with flute and sax harmonising together. Another good solo from Pete and Steve appears again on organ at the end.

‘The Waiting Song’ – This is one of my teenage angst songs. We never played it live, and it sounds somewhat naive to me. Steve added some organ.

‘The Sound of Musick’ – The Bonzo Dog-like comedy opening leads into our jamming, a bit like Canned Heat’s Boogie, with everyone taking a solo before ending with a theme of sorts. Steve played the studio’s upright piano. The tape ran out, giving an unexpected end that we quite liked.

Did you play a lot of gigs back then? What was the local scene like, and are there any particularly memorable shows?

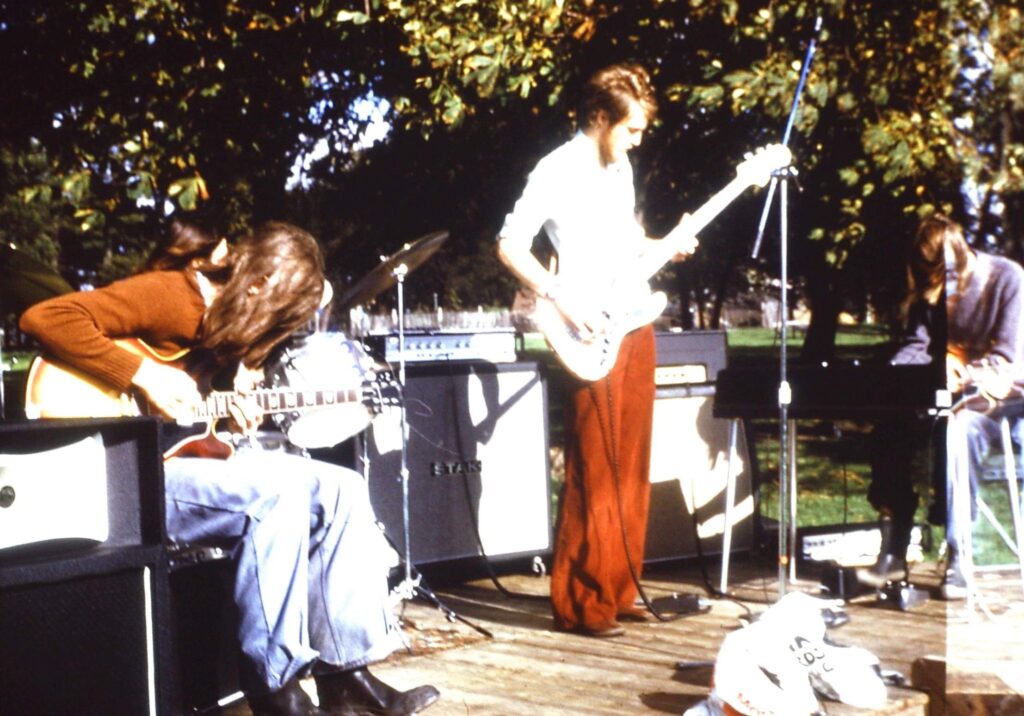

As I recall, this line-up only played four or five gigs – two school concerts and a couple of local church hall gigs.

What about the local press or radio, did you get any attention back then?

No, none at all! I don’t think we actually tried to get any.

I’d love to hear about the studio you hired and what the recording session was like. Who was the producer?

The studio was Eden Studios in Kingston upon Thames, very local to us. I believe the studio moved to Chiswick in London about a year later and continued there until 2007.

I’m not sure it was produced as such; there was just an engineer whose name doesn’t appear on the acetate. We just played everything live, and it was probably mixed in real time.

One thing I remember about the session was that it was very cold in the vocal booth where I was playing the flute. I would start off in tune, but then as the flute warmed up it went a bit sharp, and I was constantly having to adjust it.

The engineer thought we were just going to do one song with overdubs, but no! We whizzed through pretty much our whole set in a couple of hours – one take, no overdubs. As The Ruttles put it, “their second album took even longer!”

Could you tell us more about K.C.S. Modern Music and your connection to it?

K.C.S. was a pretty old-fashioned public school, so the social revolutions of the 1960s would have been a bit of a shock for them. Pop, rock, or jazz hadn’t really been allowed there, so in 1970 when a bunch of us pupils decided to put on a modern music concert, we had a bit of a battle. Fortunately, some of the younger teaching staff supported the idea, so it went ahead and flourished and hopefully still continues.

How would you describe your sound? Did you feel any connection to the Canterbury scene, or was it just a coincidence that you sounded a bit like them?

At the time of these recordings, we hadn’t really developed a definitive style; that came later. Certainly most of us were into the Canterbury scene. Paul and I loved Caravan, and Chas and I were very into Soft Machine and Hatfield and the North.

I absolutely love the flute and saxophone playing on the album. How did you incorporate those instruments into your music?

Pete learned the clarinet at school but switched to alto sax when he first became interested in jazz, listening to Charlie Parker, Ornette Coleman, and John Coltrane, among others. I had flute lessons and played in the school orchestra. I was at that time less interested in jazz but was captivated by Jethro Tull. With Martin’s arrival in the band, Pete and I played less guitar, so it seemed natural for us to hand over the main writing to Martin and go down the jazzy path with sax improvisations and a bit of flute, which seemed to work quite well.

What about other gear? I’m talking guitars, amps…

My memory gets a bit hazy here!

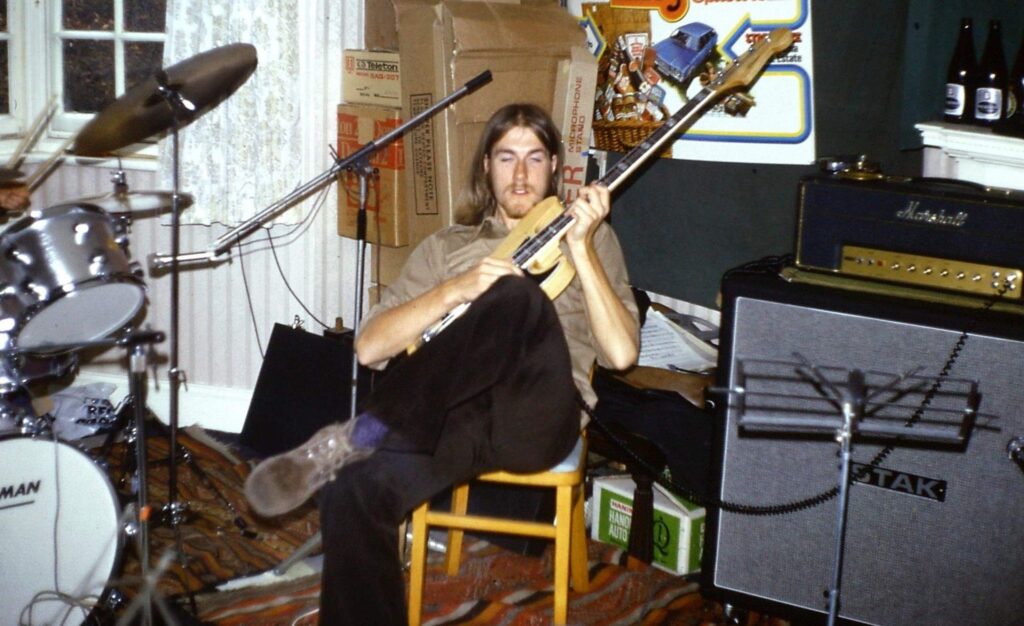

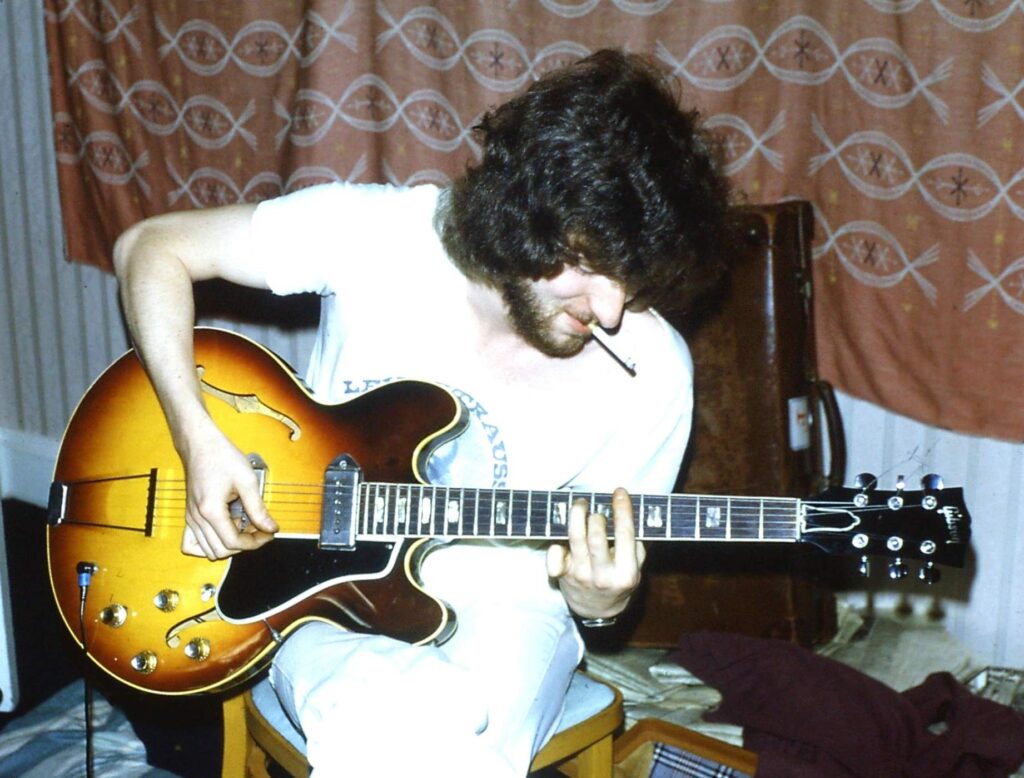

I think Martin was still playing a Watkins Rapier at this time. During the 60s this was a more affordable guitar than a Fender Strat. He put it through a Marshall 100-watt amp with a 4×12 cabinet built by Pete, Celestion speakers I think. Later, when his playing became more jazzy, he switched to a Gibson ES 335. He sometimes used a Cry Baby and Fuzz Face effects pedals.

Paul played a semi-acoustic short-scale bass, something similar to a Hofner Beatle bass, but I’m not sure what make. Framus? I know later Pete built a copy of a Gibson SG bass and used the pickups and hardware from this.

Chas at one time had a Hayman drum kit with Zildjian cymbals, but this may have been later.

Steve at first had a cheapish electronic organ (Farfisa?) then switched to a Wurlitzer electric piano.

Pete played an alto sax, possibly a Selmer or a Boosey and Hawkes.

My flute is a Boosey and Hawkes Regent, which I still have, although sadly it hasn’t been played for years. I can’t remember why I decided to play the rhythm guitar parts in the studio on an acoustic rather than an electric, but it seemed to work ok. Live, I had been using an old Vox EL-something archtop electric, but I may have just sold it by then. Chas owned a battered old Hofner electric that I used once or twice, but it was a pretty terrible guitar. I can’t remember the make of the acoustic. A couple of years later, I bought an Eko Ranger 6-string acoustic, built like a tank and still sounds fine today.

When did you stop playing together?

This line-up ceased in September 1972 when Pete and Paul went off to university.

What followed for the band members? Was anyone involved with music later on?

The remaining four of us continued playing for a couple of years until Steve left to go to university. Steve later continued playing with his own combo called Steps (not the pop group) and recorded an album that included bassist Hansford Rowe. He also played with quite a few well-known names in the jazz world, including Hugh Hopper, John Etheridge, Phil Miller, Elton Dean, and Tim Crowther. I believe he was briefly a member of Barbara Thompson’s band and also did one tour with Dave Stewart and Barbara Gaskin. Unfortunately, I have no idea where he is now.

Similarly, we have also lost touch with Martin. After Zeitgeist, he and I briefly played in a jazz quartet with flautist/composer Dave Heath. After this, Martin changed his surname to Hickey, gave up the guitar, taught himself to play piano, and became a composer of experimental pieces. Some of his works have been performed by John Harle, Nigel Kennedy, and Dave Heath. In the late 1990s, he also worked with me on some production library music pieces.

During the late 70s and early 80s, Chas and I played in a band called Private Patients, doing the rounds of the South London pub rock circuit. Chas still continues to play in various amateur bands, mainly as a singer. He had a career in the NHS as a chemical pathologist.

Paul became an academic and a successful writer, but in the early 1980s was part of the Manchester group Dislocation Dance, who recorded a couple of sessions for John Peel on Radio One.

Pete largely gave up music and became a successful businessman. He tragically lost his life in a microlight accident in 1992 while attempting a cross-channel flight for charity.

I worked for the BBC in the late 70s and early 80s, then for London Weekend Television in the 90s. In the late 1990s, I started to write production library music for various publishers – Music House, Match Music, Standard Music, and Chappell. Then around 2000 I started my own music company, Wonderweb Music, which is still producing library music today. Recently, I have also been experimenting with plant music, collecting data from trees and plants to convert into MIDI signals and then produce music. All my music can be found on Bandcamp under Adrian Carson-Smith or accessed via wonderwebmusic.com.

And what about today? What currently occupies your lives?

Well, apart from supposedly being retired and drawing our pensions, life is still quite busy, mainly family-oriented with grandchildren etc. I keep in touch with Chas, and he keeps in touch with Pete’s widow Val. We managed to track Paul down, now living on the south coast in Sussex. However, despite all our efforts, we cannot find Steve or Martin.

What would be the craziest story from those days?

Well, I think the craziest story is the finding and release of that recording session we hurriedly made and then virtually discarded over 53 years ago. I mean, that is strange, isn’t it?

Thank you for taking the time. The last words are yours.

Thanks for reading this. I’m proud to share some of this personal history, as music has always played a big part in all our lives.

Klemen Breznikar

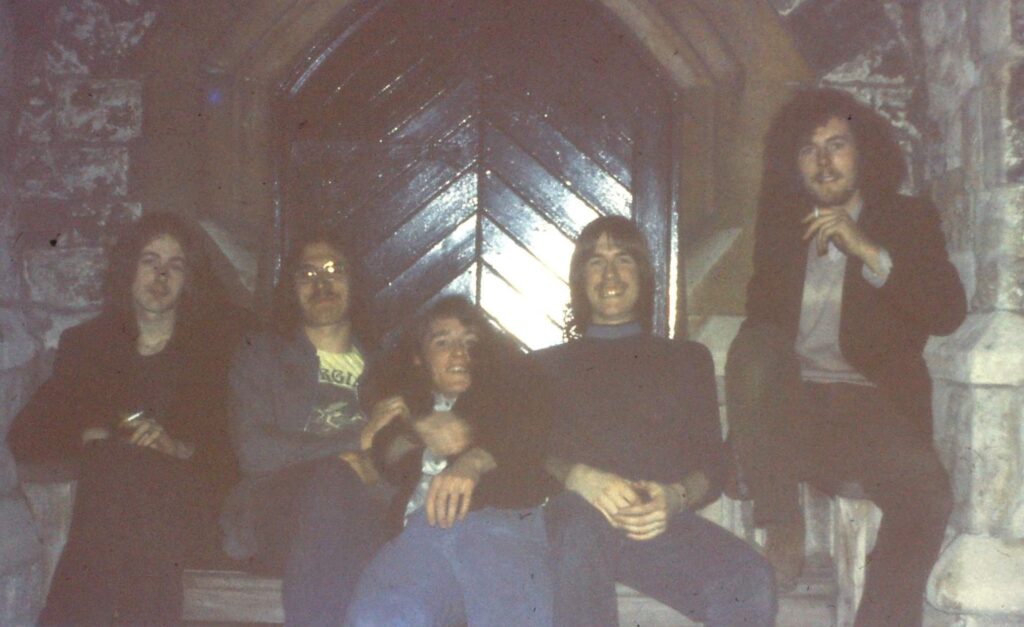

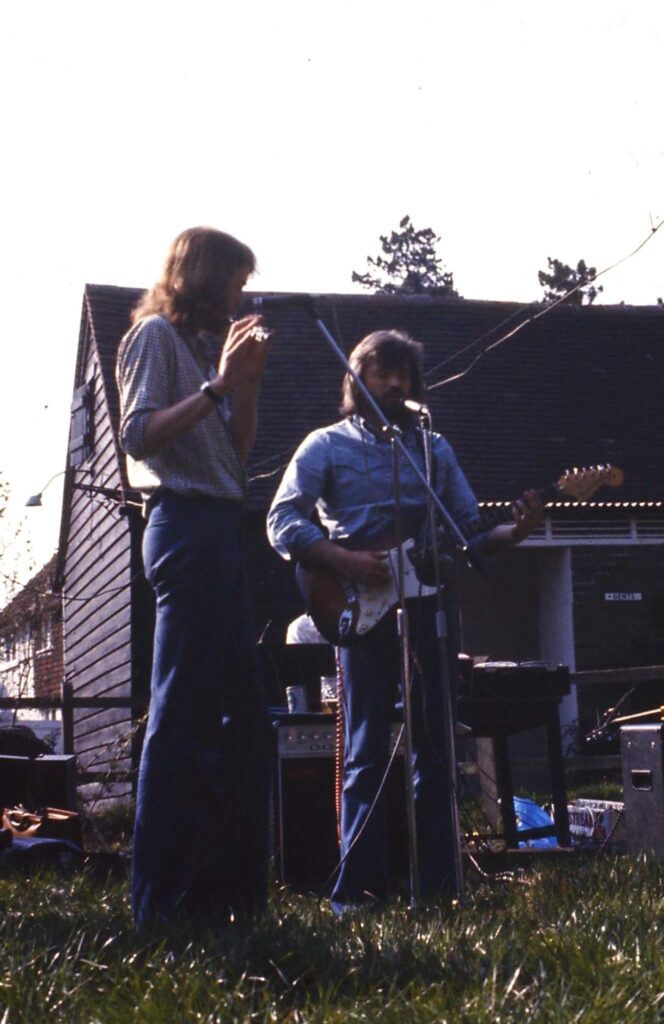

Headline photo: Zeitgeist at the Black Horse gig with Alan Bailey, 1975. Left to right: Alan, Martin Woloszczuk, Adrian Smith.

(All photos: Adrian Smith private collection)

Bright Carvings Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / YouTube