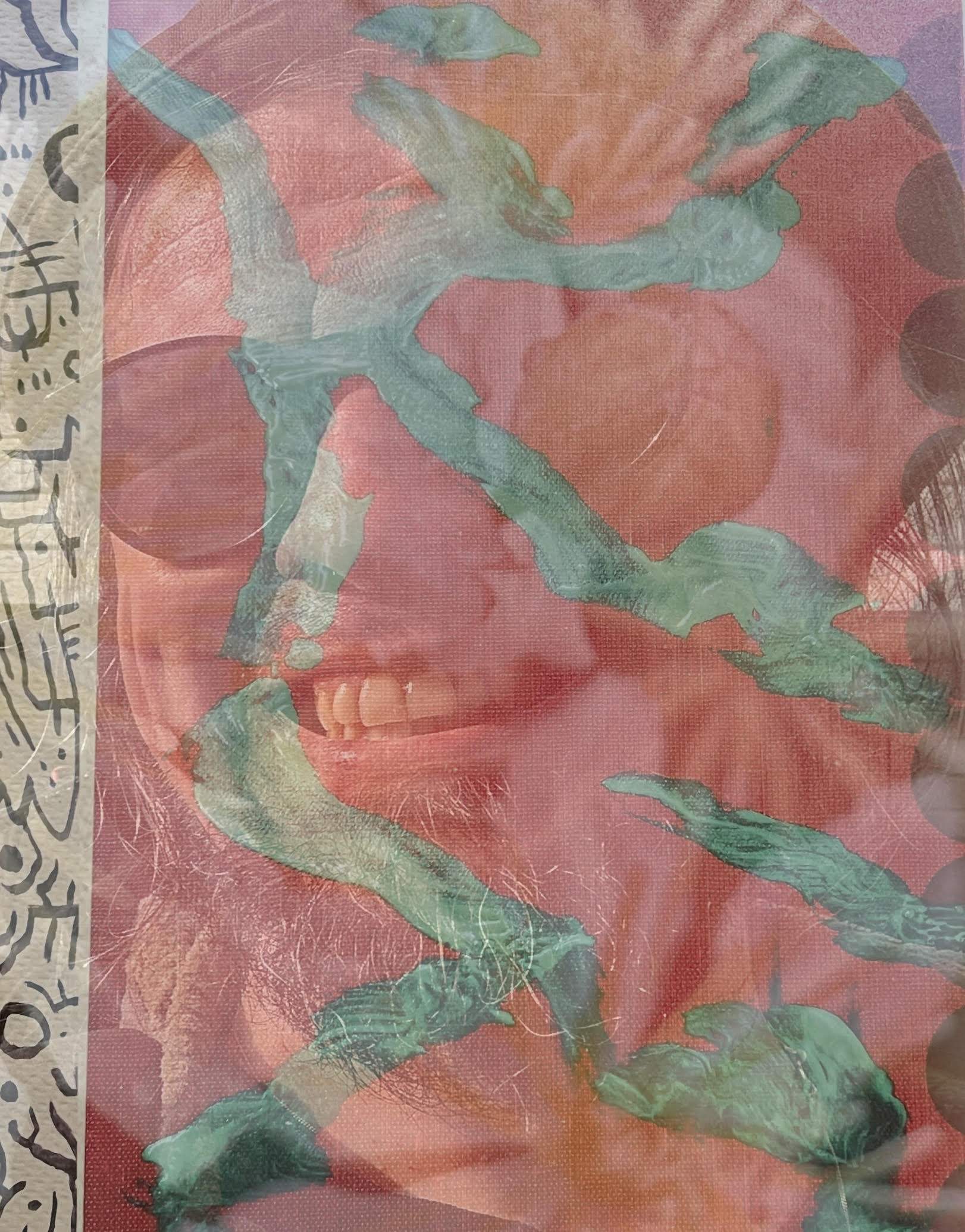

Uton on Making Experimental Music by Letting Go

Finnish sound artist Uton approaches music as a process of discovery. His new album ‘Unusual Suggestions’ continues his long exploration of texture, improvisation, and pure chance.

In conversation, he speaks with calm clarity about his methods, describing how instrumental energy meets careful editing and how accidents often lead the way forward. Rather than working from a set concept, Uton lets intuition guide him. Old recordings, field sounds, and forgotten fragments become building blocks for something new. He avoids analysis during creation, preferring to play freely and make sense of it later, if at all. “I let loose and dive into the flow,” he says, reflecting a process that values instinct over control.

For Uton, music only truly exists once it reaches a listener. Meaning, he suggests, is not fixed in the recording but shaped in the moment of listening. The result is an album that is open and grounded, experimental yet approachable. ‘Unusual Suggestions’ captures an artist comfortable with uncertainty, using it as a way to keep sound alive and full of possibility.

“I let loose and dive into the flow, driven by feeling.”

You’ve described a central aim of the album as preserving a “primal energy” or “raw power” while applying a “refined and attentive finish.” This dialectic between the untamed and the cultivated is a recurring theme in experimental sound. Could you elaborate on how this tension manifested in your working methods for ‘Unusual Suggestions’? Were there specific moments during the collage and processing phases where you felt this balance was particularly precarious or revelatory, and how did you navigate that creative friction?

Jani Hirvonen: I wouldn’t exactly say that was the album’s goal, but rather it just happened that way, though the connections between raw and refined elements are, of course, interesting and fascinating. The rawness came through mainly on the instrumental side, while the mixing and editing process involved more of a magnifying glass and various microscopes (not to mention stethoscopes). Of course, these two different forces are present in both aspects of production, though sometimes they’re just more hidden. When I play, I don’t analyze; I let loose and dive into the flow, driven by feeling. The text I wrote afterward to describe the recordings is more of a reference to what kind of music or art this album represents. That’s the analytical side, which I didn’t consciously think about while making the album. And even that analysis was fairly quickly dashed off. Since this tension between the two elements wasn’t intentional but rather a natural way of working, I didn’t feel the friction or delicate balance you mentioned (not to say it wasn’t there, perhaps).

Sometimes I might linger longer on certain parts during mixing and editing, but generally, I reach the final solutions through fairly impulsive and spontaneous experimentation, or if we go off track, we return to the path and try another way, splashing in different directions until the target hits and “hallelujah” rings out. Pure rawness alone isn’t a very robust option. It’s like a wild dog that jumps in your face and bites your thigh, but when well-trained, it’s beautiful, and its natural fruit shines through. Still, it can be intimidating (thanks to those untrained dogs that ruined the reputation of sweet fruit).

The heavy processing you mention, which renders the original instrumental sources unrecognizable, suggests a palimpsestic approach to sound, where layers are added and erased, leaving only ghost traces of what came before. How do you conceptualize the relationship between the original sonic event, the improvisation, the field recording, and its final, transfigured state on the album? Does the intentional loss of origin create a new kind of “truth” for the sound, or is it a deliberate act of sonic obfuscation?

I must be grappling with those things you mentioned in an incomprehensible way, because when I now open the jar where those pieces live their own lives, I can’t get a grip with my steaming hand. It’s as if my entire consciousness has vanished into the chaotic lushness of quantum physics. But one can try to approach the subject differently, for instance, by sitting on the sandy shore by the sea:

When the first layer of sounds, in this album’s case, improvised playing on various instruments, has been laid down and we’ve moved past the next phase of creating a collection of loops, it’s time to combine these ingredients to form rough drafts, so-called songs. After that, more stuff is layered on top until it no longer makes sense to add anything (and it doesn’t always need to be much). Whether the original sound has been deliberately diffused or not is merely a matter of chance. The process isn’t driven by a need to fulfill some prewritten style or ideal thought pattern, but rather by giving space to breath and breezes, without traps or war axes, though their existence is hinted at by their hanging on the barn walls, just in case someone might want to borrow them (though I must say, the trap is a bit broken).

No conscious blurring of sound has been practiced. Rather, these furnishings have been guided into their own channels and natural, yet also intriguing, positions, and captured from different angles through various lenses, even using moving images. A kind of feng shui, if you will, without making a big deal out of it (or even a letter).

You state that you used “previously recorded field recordings” and “some other sounds from the archives.” In an age of infinite digital storage, the archive itself becomes a generative space. How do you approach your own sonic archive? Is it a repository of past failures or successes, or a living library of potential, where sounds acquire new meanings through recontextualization? Does the act of “digging into” these archives change your relationship with your own musical history?

When I use sounds from archives for my tracks, I mostly browse through three main folders: field recordings, samples, and the “audio” folders from previous album projects, which include not only sounds used on the records but also material that didn’t make the final cut. The sample section contains some previously edited sound snippets and loops, while the field recordings range from nature sounds to all sorts of things captured indoors and outdoors. I use these archived sounds sometimes as they are, or by taking just parts of them, and also by editing and adding effects to fit the track. So, defining the archive as a potential library for new meanings is certainly a workable approach.

I don’t exactly dig deep into my archives, perhaps because those sounds are so readily and quickly accessible that I can just pick the berries without sticking my head into the soil. Of course, a broader version of the archive extends underground to old cassettes and hard drives, but I don’t feel the need to go on that kind of journey.

You refer to your 2008 album ‘Straight Edge XXS’ as a “sister or at least a cousin release” to ‘Unusual Suggestions’. Given the considerable time span, what specific methods from that 2008 work resurfaced in this latest album? Do you see your discography as a linear progression, a series of recursive loops, or a network of interconnected conceptual nodes?

The connection between those recordings lies in their forms of expression. Both albums consist of various short pieces that jump across a fairly wide range of styles, though upon enough listens, their own connections become apparent. Sometimes there’s a need to create this kind of “cross-section” of different styles, because I’m personally interested in many kinds of music, and I want to express that through my own channel. I’m not interested in being confined to a single mold, like only making drone or ambient music, because I feel I’m more than that. Certain things do repeat in some way, but I always aim to bring something to releases that deviates from previous ones of a similar type, even if an untrained listener might not necessarily notice.

In Uton’s early days, I might have seen some of the linearity you mentioned, but at some point, it naturally veered off on its own path. It felt almost wrong and forced to keep the expression faithful to that kind of linearity, to a traditional or generally assumed continuum. I’ve given in and just started splashing around based on what feels right. Sometimes, if it feels like it’s going too far beyond the current vision, I’ve come up with an entirely different name for the project, like Pupil Wah, Yksi, Profeetta Elämän Äänikoulu, Dio Daga, Saatanan Pässi, The Brain Dwarf, and so on. All these intuitive creations are parts of the same whole and thus intertwined with each other, just as Uton is part of a larger, more incomprehensible picture.

The final sentence of your notes, “More important than these explanations is the sound itself, how it feels inside each listener,” shifts the focus from your creative intent to the listener’s affective experience. This raises questions about the work’s intersubjective nature. Do you consider the album’s meaning to be fully actualized only in the moment of its reception by the individual listener? To what extent are your compositional choices guided by a desire to evoke a specific emotional or sensory response, or is the process a more hermetic, introspective one?

Without a listener, meaning remains rather insignificant, but when a listener is present, observing, meaning takes on new forms and nuances. When the meaning becomes an emotional experience for the listener, the music shapes the mind on a collective spiritual ground, to a lesser or greater extent, depending entirely on the charge the experiencer feels. Ultimately, the experience comes to life in interactions between people and, at its best, sparks new positive experiences, inspiration, art, moments, and so on. This applies to everything, not just this album.

The image this particular album conveys might be quite introspective and self-reflective, but it could also be something entirely different. When making and producing the music, I haven’t thought about it needing to evoke a specific reaction in listeners, except perhaps the hope of providing inspiring moments through the music. At its best, it creates energetic transitions into something new and captivating, with lasting, positive effects on the listener’s life.

“Sometimes it’s good to let go of what was planned and not cling to a so-called finished idea.”

The use of spontaneous improvisation combined with pre-recorded elements suggests a reliance on chance and synchronicity in the compositional process. To borrow from Jungian psychology, were there moments of “acausal connecting principle”—meaningful coincidences—that occurred during the making of the album, where seemingly disparate sounds or ideas came together in an unexpectedly potent way? How do you distinguish between pure chance and a form of artistic intuition?

I don’t recall any specific details about the album’s recordings in that regard, but generally, my approach to creating and producing is to let chance bring ideas along. Sometimes those ideas are remarkably useful and enchanting, and then it’s good to let go of what was previously planned and not stubbornly cling to a so-called finished idea. So, it’s wise to keep your eyes open to take advantage of that open vista. Whether the direction ends up being the right one, and how one could even evaluate that with reason, is another matter entirely, but if the trajectories have led to a result, you can surely say a kind of satisfying answer has been found: a living tissue or tapestry, ready for the universe’s play. If something’s still off, it can be molded a bit longer (but not too much).

As for the last part of your question, I don’t make that kind of distinction in any particular way. I don’t find it necessary, as it feels too analytical to allow for fluid creation. My musical process is pretty far removed from theories and that sort of academic amusement and enthusiasm. Some folks are into that, but I don’t have the education to have wired my brain for it.

The track titles for the album, ‘instructions and creative ideas for the confused humanity (and how to break the walls of self deception)’ and ‘interesting and relatively unusual suggestions for the mind opening and to praise the freedom of life’, are incredibly verbose and almost didactic. They stand in stark contrast to the abstract, collage-based nature of the music itself. What is the relationship between this highly specific, linguistic signposting and the non-representational, textural sound of the pieces? Is it an ironic gesture, a conceptual framework, or a guide to the listener’s perception?

I could have, of course, chosen not to name the tracks or these collections of short pieces, but that’s always the more boring and lazier option (at least in this case). Since I find certain spiritual matters important in my life, I wanted to infuse the names with something that reflects my inner thoughts and hopes. Even though the names and the music might seem at odds with each other at first glance, I don’t believe that abstract, vaguer sounds can’t be harnessed with these given words and prompts (suggestions).

The connection between the human mind and the world is so multifaceted and peculiar that it’s no wonder these threads can produce all sorts of clangs and hums, especially when you give yourself the freedom to navigate through the different layers of the mind. These soundscapes are vast, and you can only draw out something from them, and that something is what it is. The sounds follow the thought, even if that thought hasn’t yet been spoken aloud during the production process. Once it’s finally written down, the sound begins to follow the path it lays out. But it needs a new interpreter, a listener, who gives it their own wings and eyes. So yes, those names could be seen as a kind of “guide,” but by no means an ironic gesture; I don’t waste my time on that sort of thing in a project like this.

Field recordings can be seen as a way of capturing the unique sonic topography of a specific location or moment in time. When these recordings are integrated into your music, do they retain their original geographical or temporal identity, or are they completely de-territorialized, becoming pure sonic material? Do you view your work as a form of “aural geography,” and if so, what kind of landscapes are you constructing?

For this album, field recordings were used only as building blocks to create additional atmosphere or color in certain parts. These kinds of sounds are distinct compared to those made with instruments, so they can bring different nuances to the tracks. It doesn’t matter whether such recordings were made in a shop, a kitchen, or a forest; they’re going to be mixed in with everything else anyway. You can also take small snippets from field recordings and play them with a sampler, turning just about anything into an instrument, or at least an essential part of one.

In some of my other albums, not necessarily under the Uton name, the locations of the field recordings hold more significance in relation to the album’s concept.

You mention that after a year, you couldn’t easily recognize everything you had played on the album. This act of forgetting, or being unable to “re-cognize,” is a powerful one. How does this kind of sonic amnesia affect your perception of your own work? Is there a certain freedom in no longer having a definitive memory of the sound’s origin, allowing it to exist as a pure phenomenological experience, both for you and the listener?

The fact that I don’t remember exactly what I’ve done or what equipment I used doesn’t really affect my perception of my own work. It’s certainly intriguing to later listen to something I’ve made and sometimes be baffled by the lack of memories about it. At times, I even wonder if I’m the one who made what I’m hearing! And of course, it’s common among artists to say that art comes through them, without control (though the artist’s own filter or mold has been created at some point, consciously or unconsciously). It’s like being in a kind of trance. This comes up more readily in improvised music, whereas composing involves more pondering and calculation. For me, this so-called composing happens during the editing and mixing phase.

I can’t think of anything more to say about these questions right now. I could, of course, ramble on about it all for hours or days, but let this be it for now. I invite those reading this to come and listen to my music; there’s a lot of it, and it’s varied, but always leaning toward the experimental, often quite sharply.

Klemen Breznikar

Uton Website / Instagram / Bandcamp

L’Eau des Fleurs Instagram / Bandcamp