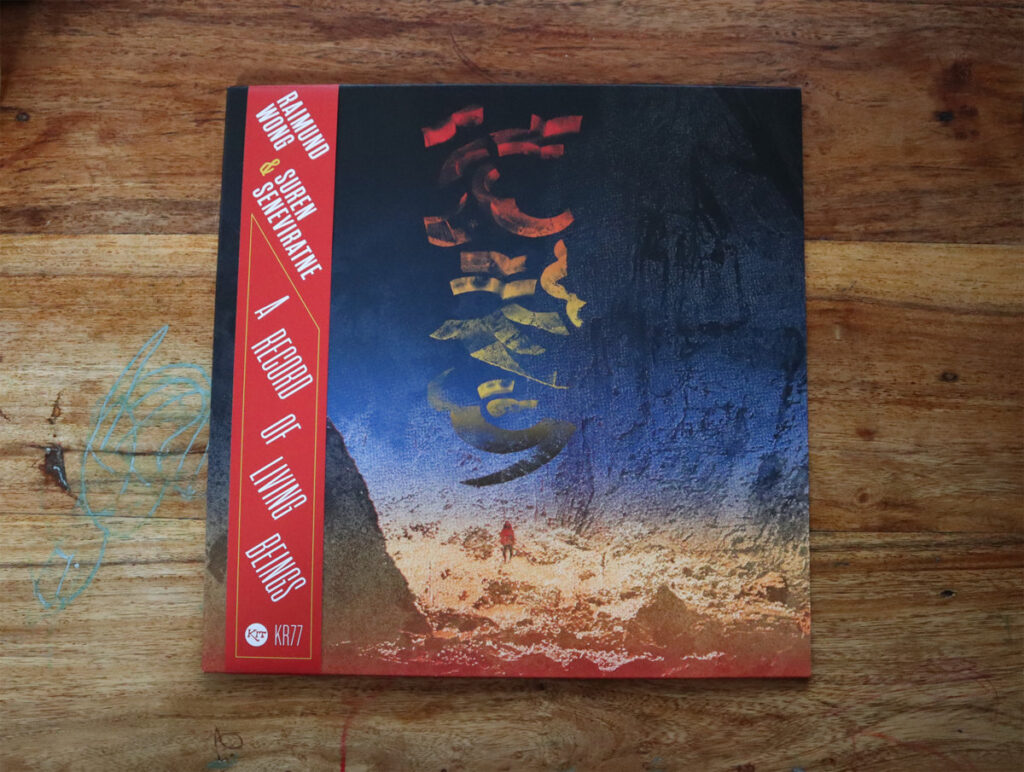

Exploring ‘A Record of Living Beings’ with Raimund Wong and Suren Seneviratne

‘A Record of Living Beings,’ the collaborative project of Raimund Wong and Suren Seneviratne, goes beyond conventional musical composition to become a layered, time-spanning exploration of sound.

This work, emerging from the improvisational ether of Wong’s radio broadcasts, performs a remarkable temporal and cultural synthesis, manifesting a sound world simultaneously archetypal and post-human. The album’s singular texture derives from an audacious intermingling of the venerable and the obsolescent digital. Acoustic instruments of deep historical resonance, such as the khæn, the shakuhachi, the taishogoto, and the cello, engage in dialogue with magnetic tape loops and the distinctive, granular artifacts of rare 1990s Macintosh software, creating a deliberate act of temporal dissonance where the breath of traditional woodwind and string instruments meets the precise, looping logic of early digital sampling and manipulation.

The duo’s fascination with cross-cultural pioneers like Yellow Magic Orchestra and Geinoh Yamashirogumi informs the album, yet the result is unmistakably their own. Each discrete track functions as a fleeting aural montage experienced from a rapidly moving perspective, forming a patchwork of recalled aural memories, spectral echoes, and architecturally imagined landscapes, all intricately stitched together. The music unfolds as a meditation, embodying a paradoxical spirit: optimistic in its forward motion yet deeply introspective in its texture; playfully experimental yet meticulously sculpted. It features musicians Clive Bell (Jah Wobble), Maxwell Hallett (The Comet Is Coming), Seaming To, Dominic Kennedy (Uh), Yoshino Shigihara (Yama Warashi), and Francesca Ter-Berg (Fran & Flora). The album was produced by Raimund Wong (Floating World Pictures) and Suren Seneviratne (My Panda Shall Fly).

The title, ‘A Record of Living Beings,’ comes from Akira Kurosawa’s film, a powerful, albeit bleak, look at existential dread and paranoia. Your work, however, is described as “optimistic and convivial.” That’s a fascinating contrast. Could you speak to this seemingly paradoxical relationship? Is the optimism a defiant response to the dread, or is there a more nuanced connection you’re drawing between the film’s title and your sonic world?

Raimund Wong: The throughline between the ancient, the tape-recorded, and the digital is a literal reading of the album title: they are all documents of a people’s activities and use their power to conjure memory, making associations across disparate space and time through harmony and dissonance in sounds and voices.

One of my earliest movie memories is Kurosawa’s 1990 anthology film Dreams, which has the most direct impact on this project as well as my work in general. From there I came across his film I Live in Fear (Record of a Living Being), and the title suited my objectives perfectly. Both films deal with themes of impending death but also the responsibility of the survival of others—this is where the sense of hope comes in. The basis for most of the songs came from tape loops, and the cycle of death, creation, and life is also represented in the sound-on-sound methodology of tape loop making, where a fertile aural environment is created by continual self-renewal through destruction and generational memory.

You’ve woven together a fascinating mix of traditional instruments and esoteric software—everything from khæn and shakuhachi to obscure ’90s Macintosh programs. How do you navigate the potential clash between these elements? Is the goal to seamlessly blend them, or is the tension between the ancient and the digital a fundamental part of the album’s identity?

Raimund: By putting these numerous and contrasting textures against each other, and keeping their origins as varied and esoteric as possible, the music strives to speak of places and peoples of different times and circumstances. So for me it feels less like a risk of clashes, and more about throwing it wide open for interpretation and interaction.

Suren Seneviratne: There is very much a tension that will inexplicably arise from bringing together such disparate instruments and elements, but this is where I find the magic lies. I’m a big fan of the genre dubbed ‘Fourth World,’ which, despite not being easy to put into words, often marries unusual instrumentation through a digital or electronically treated fashion. That’s something that has guided some of the production philosophy on this record, even if subconsciously.

The album is described as documenting “a borderless ensemble spinning dialogues around ‘otherness’ and the fracturing of cultural and personal identity.” Could you both speak to how you, as a collective, approach these heavy themes? Do you find that the improvisational nature of your sessions allows these concepts to emerge naturally, or is there a more deliberate, perhaps even intellectual, framework you’re working within?

Raimund: Taking inspiration from Yellow Magic Orchestra’s cross-cultural subversions, I wanted to explore the dichotomy between traditional and experimental, and do it with the voices of the experienced and aurally adventurous, so that we were best positioned to have these simultaneous dialogues about self and others, culturally and personally, through improvising in a group all together.

The press release makes a bold comparison to the work of Yellow Magic Orchestra and Geinoh Yamashirogumi. These groups were pioneers in integrating traditional cultural forms with cutting-edge technology. How do you see yourselves carrying that torch forward? What new ground are you breaking, or what conversations are you continuing, that are unique to the 21st century?

Suren: Those groups are among the very few that Raimund and I both happen to obsess over. They were so pioneering with their sonic sensibilities and studio production, and while we don’t claim to be anywhere near as good, they have been inspirations for a long while, so something of that aesthetic and approach will no doubt have spilled over into our work.

Raimund: The information overload and hyper-connectivity of our age are perhaps aspects that are added into the conversation brought on by those pioneers. When you have access to everything at all times, it feels special to be in a room communicating with individuals in a very selective manner.

The album grew out of your freeform radio show. Can you describe the evolution from a live broadcast to a structured album? What was the editing and arranging process like? Did you go into the studio with a clear idea of what you wanted to achieve, or was it a process of capturing moments and then building a narrative from that raw material?

Raimund: The radio show had lots of live segments where I improvise with guests, so it was a natural progression to transition into a recording project. On most pieces, I provided tape loop pieces to set the tone and environment. Then in the studio it was definitely about trusting the collaborators to react sensitively to each other and to the material. Sometimes an approach would be hinted at on the first take, and we’d refine it further on a second take. In most cases, the arrangements are quite close to how they were performed, but much work was undertaken to tighten up the structures and put in analogue and digital treatments.

Farewell (Jen) was the notable exception to this. The takes in the first session weren’t satisfactory, and we finally found the propulsion it needed with Dom joining in on bass on the second session. Then lots of editing and live-dubbing took it to its final form.

As an audio-visual artist, how does your visual sensibility influence your work as a musician and collaborator? Do you “see” the music in a particular way, or do you have a visual language in mind when you are creating or improvising?

Raimund: My background in printmaking has a significant impact on my practice. The discipline of print is based on the dynamic interactivity of layers and uses texture as one of its prime tools of communication, both of which are directly connected to my approach to using loops with the cassette 4-track. Two of the main routes of print are mark-making in a blank space and the casting of light into darkness—both of which can easily be seen as interpretations of sound creation, collaborations, and improvisations.

The name “Floating World Pictures” evokes the Japanese art of ukiyo-e, which often depicted transient, everyday pleasures. How does this concept of the “floating world” inform your artistic practice, especially in a project so focused on capturing fleeting, improvised moments?

Raimund: FWP is the name of another group I lead, and the name comes from my studies in printmaking.

The press release mentions “dub manipulation” as a key element. Dub music is inherently tied to a sense of space, echo, and deconstruction. How do you apply this aesthetic to an ensemble that features traditional acoustic instruments? What are you “dubbing out” or “echoing” in a project that is already so atmospheric?

Raimund: This relates to my live and recording setup, which utilises 4-track recorders and mixers as instruments, in a practice much informed by the language of dub but also the chance-based systems of musique concrète. Feedback is used to treat and deconstruct both live instruments and pre-recorded loops on cassettes, augmenting tonal and rhythmic characteristics to create an uncanny distinction from their original source and expand upon the sound world.

You’ve brought together a diverse group of collaborators from different musical backgrounds. What’s your philosophy on collaboration, and how do you create a space where such disparate voices can not only coexist but thrive and build something entirely new together?

Suren: Collaboration is at the heart of this project and how the music came to be in the first place. All the tracks were born from collaboration because many musicians created the music in real time through improvisation.

Your background includes a significant use of esoteric ’90s software. What is it about this specific era of technology that continues to inspire you? Is it the unique sonic character, the limitations that force creativity, or something more nostalgic?

Suren: You are spot on with that. My contribution to this record is largely borrowed from my solo project Missing Music, which is a living, obsolete, and rare Macintosh music software library.

The sense of nostalgia is second-hand in that I was always a PC user growing up, and so I had no idea about Mac-native software and plug-ins, even though I was noodling around adjacent to this. As I slowly started to uncover all the software tools that had evaded me all these years, I realised there was a whole universe I had been unaware of. My obsession with these newfound tools is not based on novelty; I have since relied on them for professional music work, including a short film score last year.

You’ve been involved in sound archiving. How does the mindset of an archivist—the preservation, classification, and understanding of sound history—inform your creative process as a musician? Do you see your work, in a way, as a new form of archiving or a commentary on it?

Suren: My archival practice is functional in the sense that I classify and preserve vintage Macintosh software on my blog (missingmusic.medium.com) while also keeping the software in regular use through recording and performing live.

I’d like to think this is a new kind of archiving, a hybrid form that exists with a live, in-real-life component. This is different from a practice that is traditionally known to be bureaucratic and “serious.”

The album is recommended for people who like “glimpses from moving trains.” This is a beautifully evocative image. What is the shared artistic vision that this phrase captures for you? Is it about fleeting beauty, the blending of landscapes, or something more introspective about the journey itself?

Suren: Much of the music on this record is textured, as if crafted like a sonic patchwork quilt or an assemblage of varied sound objects. This is my interpretation of “glimpses from moving trains.”

Raimund: Yes, I think you’ve touched on all the right aspects. It is the sensation of seeing the world go by, and the compositions are these momentary observations into stories and scenes that we happen upon, and then they’re gone. With the slow, brooding pieces, it’s more about a contemplation of the loneliness of travel and the relationship between the self and the vastness of the world.

Klemen Breznikar

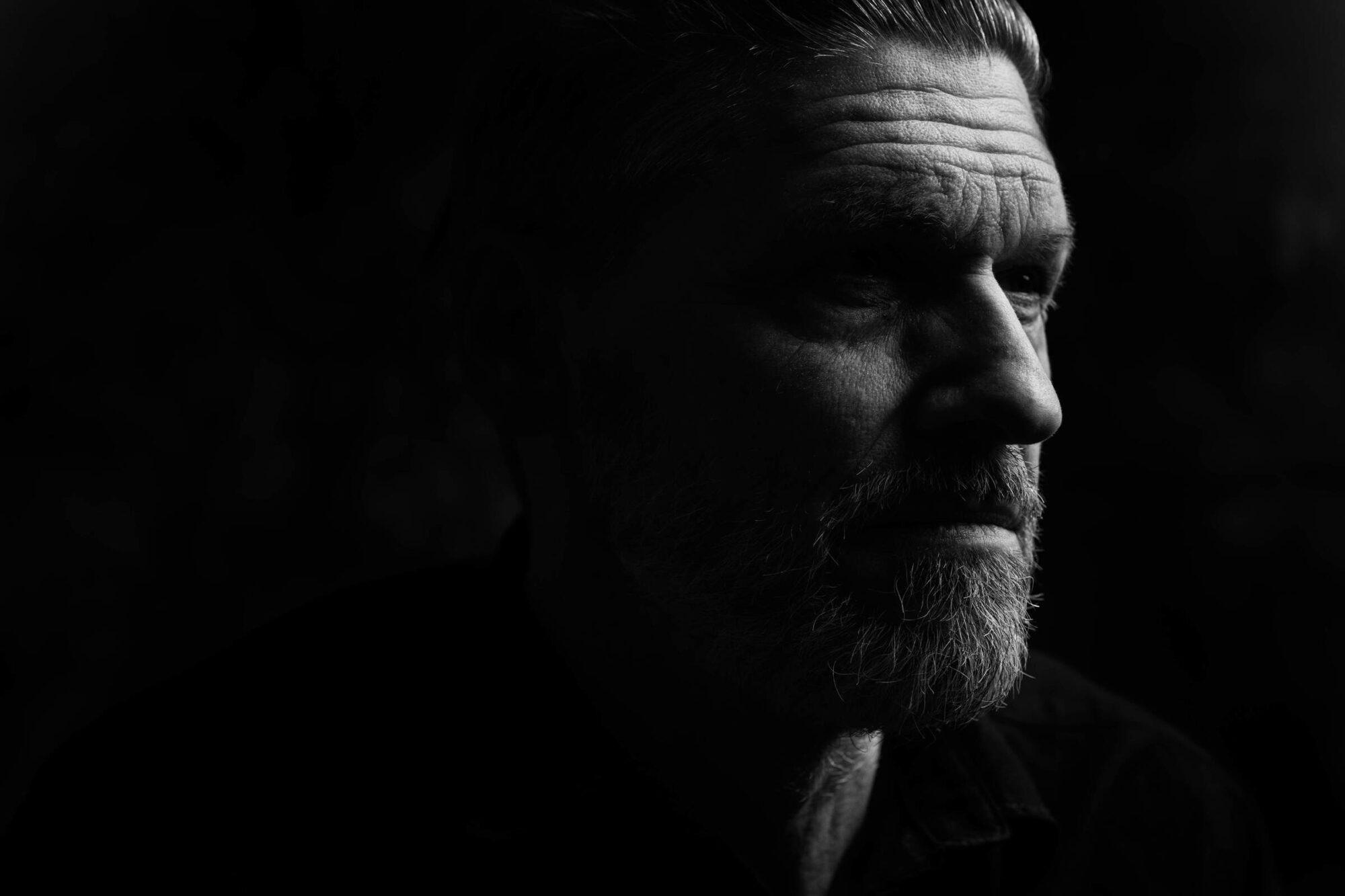

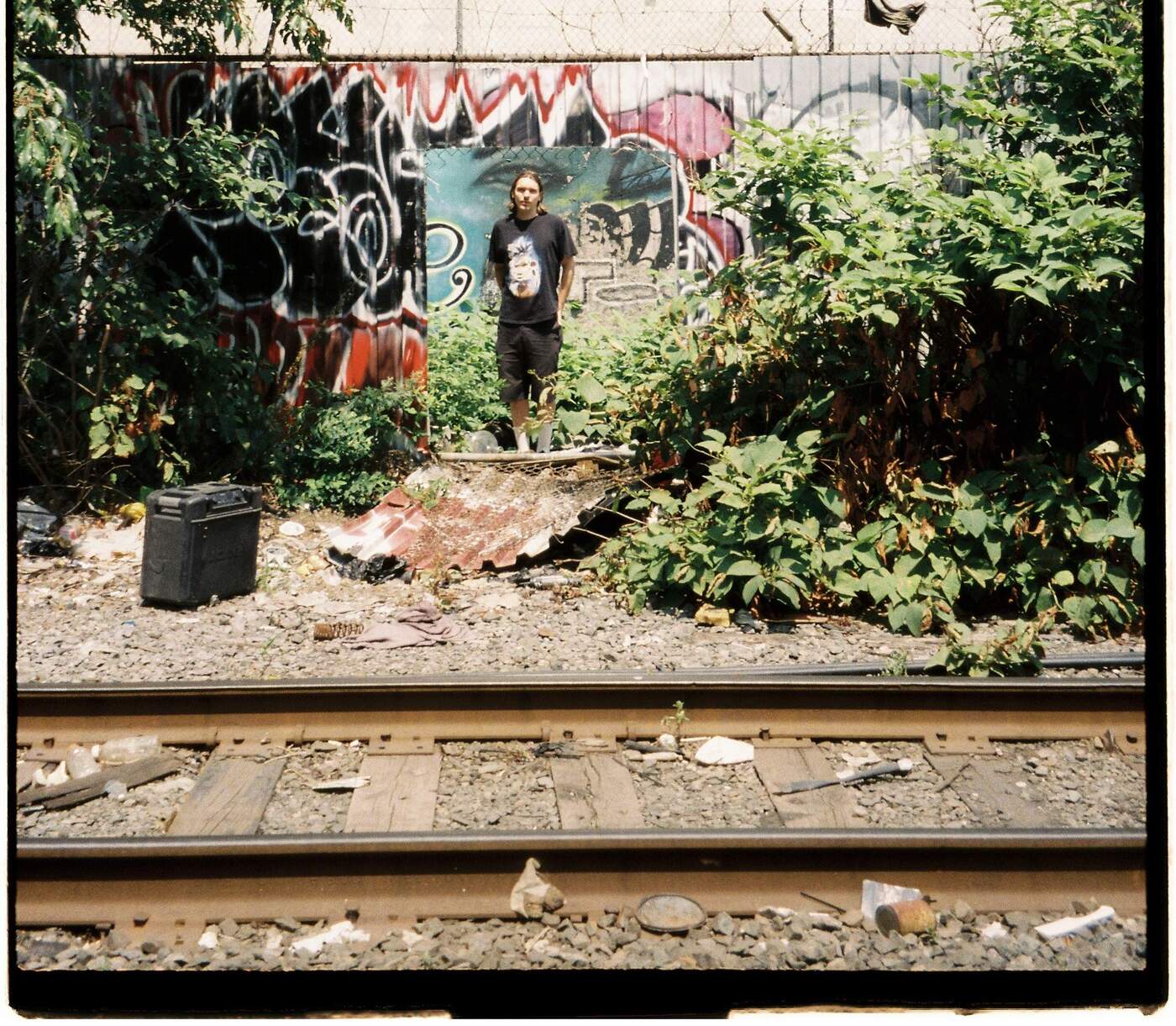

Headline photo: Suren Seneviratne and Raimund Wong (Credit: Richard Greenan)

Raimund Wong Website / Facebook / Instagram

Suren Seneviratne Website / Facebook / Instagram

Kit Records Website / Instagram / YouTube / Bandcamp