The Carlos Perón Interview: Yello’s Co-Founder Plunges Into New Single ‘Start Again’

Carlos Perón remains one of electronic music’s great enigmas. As a founding architect of Yello, he helped invent a sonic vocabulary where silence had weight, and rhythm could breathe like a living machine.

Decades later, his creative pulse is as restless as ever. Speaking with the same mixture of precision and mischief that marked his early work, Carlos treats every frequency as a burst of energy. His rhythms still carry that strange paradox: mechanical yet human, disciplined yet deeply sensual.

Today, he is returning to the raw edge of sound through a new project that fuses industrial metal with his long fascination for electronic form. He calls it a continuation rather than a departure, a widening of the circle that began with Yello’s surreal experiments in Zurich’s Rote Fabrik. In his words, metal is simply another texture, another voltage of emotion.

He works entirely within a digital cosmos of Mac systems, terabytes of samples, and the intelligent interference of AI. Yet what endures is his devotion to surprise, to tension, to humor that borders on menace. Whether manipulating voices or bending machines to his will, Carlos still inhabits the intersection of science and imagination, where music becomes both architecture and illusion.

“What mattered was experimentation”

Carlos, with ‘Start Again,’ you’ve plunged into a collaboration that fuses your electronic legacy with the force of industrial metal. The press sheet describes the lyrics as “mantraic” and carrying a “positive message.” Could you elaborate on this? How do you reconcile the aggressive, almost brutal landscape of industrial metal with a positive, repetitive mantra? What is the underlying philosophy or specific intention behind this juxtaposition of sound and message?

Carlos Perón: Yes, the mantra-like sound is in my blood. Also repetitive metal industrial, see Dark Ruler and other projects. But with ‘Start Again,’ a special mission arose: the singer Stefan Bahners asked me to produce a hard track for his band Melting Rust Opera. I was happy to do that because I was producing something similar with the singer Superstalin. I thought I’d do something in the style of Suicide. I grabbed the guitar and the Fractal and started banging and recording. The track was pure hypnosis, and I later sent the sound to Stefan. He sang it at short notice, and his shouting reached exactly those positive voices, which I then teased out even more in the mix. It’s a prayer that invigorates body and soul. So when things are going badly: ‘Start Again’.

Let’s rewind to the beginning. Before the iconic sound of Yello crystallized, there was a conceptual framework, a philosophical blueprint, if you will. Can you take us back to that moment of genesis with Dieter Meier and Boris Blank? What were the core ideas, the shared fascinations, and the artistic manifestos that defined Yello’s birth? Was it a conscious decision to break from traditional song structures, to prioritize texture and sound design over conventional melodies, and to create a “cinematic” music without a corresponding film?

Yes, it’s a complex question in itself. I started experimenting with my Grundig TK 23 L tape recorder with a trick button when I was 12 or 13. I would record things like fits of laughter and play them at school on New Year’s Eve. The pupils thought it was great; the teachers shook their heads. I also recorded shows from Europe Numero 1 (a French radio station in Paris) back then, which featured the latest songs being created at the time, all the 60s stuff. I would then edit the individual songs the way I liked the suspense.

Later on, I got a Skandyna stereo system with the latest record player at the time. I was also collecting vinyl records: Stockhausen, The Beatles, Black Sabbath, Cream, Vangelis, Klaus Schulze, Tony Williams Lifetime, Mort Garson, Suicide, Archie Shepp, Sun Ra, Jimi Hendrix, Art Ensemble of Chicago, anything new and modern coming out of the USA.

I then bought a second record player and a small mixing desk and started producing mixes with my by-then quite large record collection. And since I came from a commercial background, I came up with the idea of selling these mixes to restaurants and bars. Business was so good that I considered opening a record store with my then-girlfriend, or even founding a jazz recording studio in Ticino. I already had a logo for the record store. It was going to be called “Music Catch”.

At the time, a party was being held at the home of my school friends Sternini and Peter Frei. A guy named Boris Blank was there. We met during a discussion about John McLaughlin. Later, I invited him to my house and played him my mixes. These were characterized by particularly long transitions where you didn’t know which piece was coming next. He was so fascinated by it and asked me if he could try something out. That was actually the origin of our later collaboration.

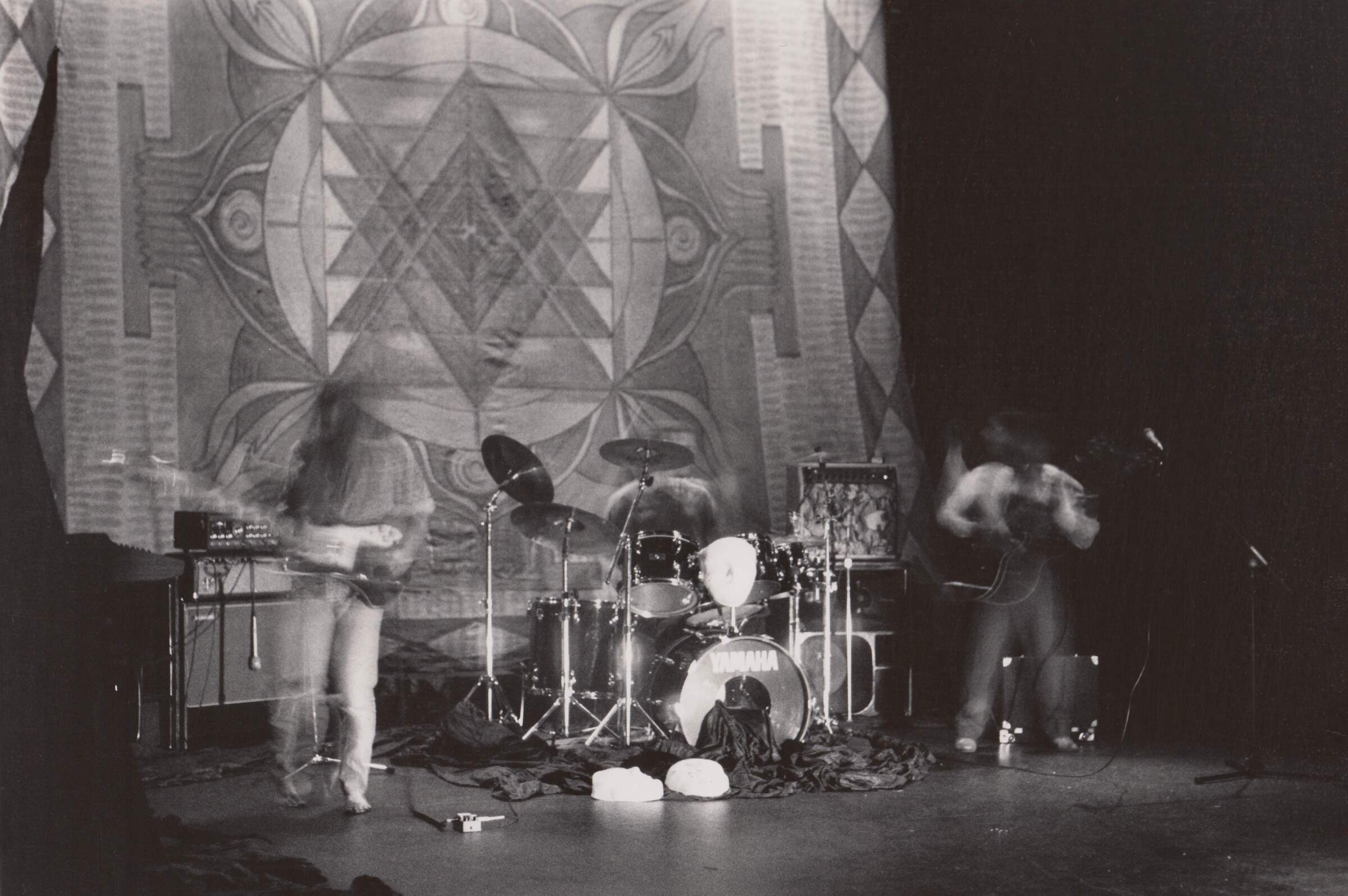

Over time, I was repeatedly asked if I wanted to join the band Urland. It was a group around drummer Sternini, Ron Styler, and, for a time, Boris Blank. Since I had just returned from a long trip to Morocco and had brought along many native instruments, I thought, why not give it a try? Urland was going through a phase where they wanted to imitate free jazz. I had to explain to the band that free jazz was composed and improvised music, and that I couldn’t detect any trace of composition. In that sense, they just jammed away. Sometimes there were short, brilliant sound conglomerations, but mostly it was nonsense. I suggested recording everything on cassette so we could check later if there was any real substance. The disappointment was great. I played a kind of hammer piano and snake-charmer horns. You couldn’t hear the instruments. I quit for a while.

Time passed. Urland asked me again if I wanted to play with them, as they were now making electrified rock. I said I’d join New Wave. I got myself a Farfisa synth orchestra, a Wersi string ensemble, and a Boss drum kit. Now I had power and sound. Blank played electric guitar, Sternini on drums, and Ron Styler on bass. So far, so good. The problem was that Sternini couldn’t keep the beat. He kept getting faster and faster and didn’t stick to rules like tapping out a simple rock beat. I then called in my boss, and Sternini was annoyed, saying they wanted to replace him with a machine.

In the meantime, Blank and I made a kind of cosmic meditation music that we called Astronic. To give Sternini a chance, I introduced him to Felix Haug (Yello’s first guest drummer). Sternini learned well, but ultimately, everything was exhausted in the so-called white powder. There was also another dispute between Blank and Sternini. I said, “I’m leaving this chaos.”

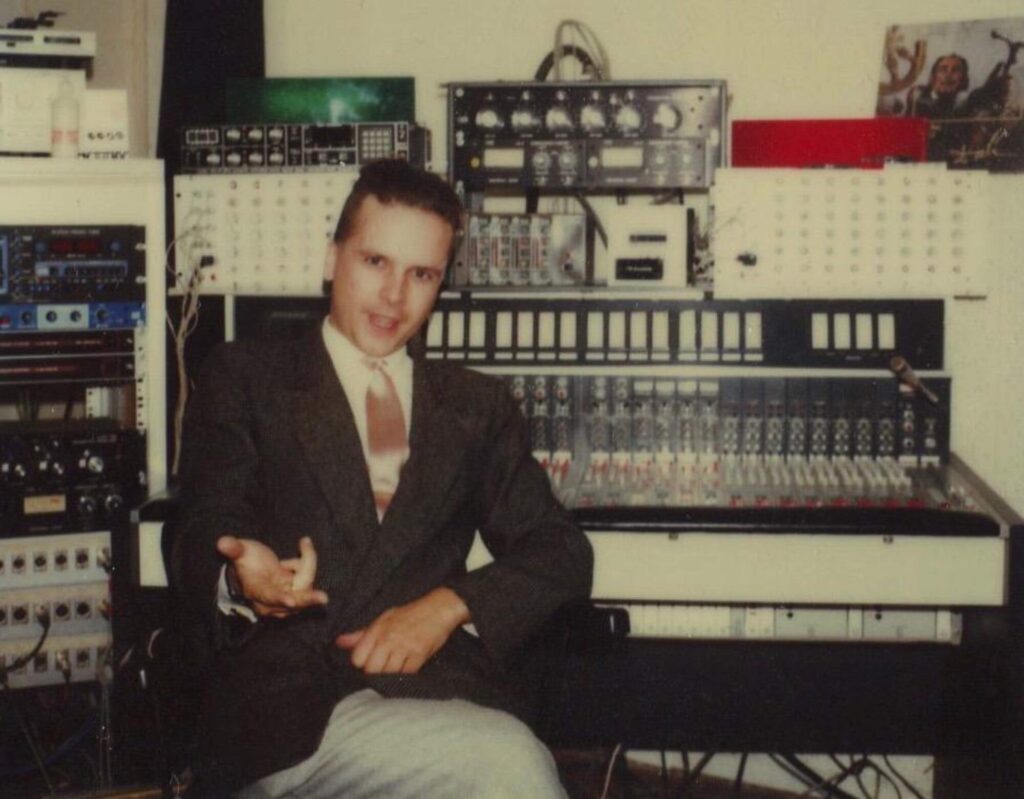

I then bought an ARP Odyssey, Quadra, a sequencer, and other gear, and built a studio in my apartment with Boris. We called ourselves U.R.Q?, Astronic, and finally Tranceonic. Boris would come every Wednesday on his day off, and we would develop our new music freely, without stress or debate. By mid-1978, we had already recorded a whole 90-minute tape with fresh music, and we decided to spend our holidays in the USA in August 1978.

We visited RCA Records in Los Angeles and Ralph Records in San Francisco. We hadn’t actually wanted to visit the latter, but rather the Chrom Studio. But this mix-up turned out to be groundbreaking. Jay Clem and Hardy Fox were enthusiastic about our recordings and offered us a contract. I was wearing my Uher Report at the time and recorded the entire conversation on cassette. When I came back, I found a telegram in my mailbox with a written offer from Ralph Records. We had actually managed to get attention in the USA.

A few weeks later, Hairi Vogel showed up, wanting to join our project with guitar. We turned him down because we weren’t particularly interested in guitar stuff at the time. Instead, I invited my school friend Chico Hablas (guitar guest player for Yello) to record guitar in my studio. This laid the foundation for later Yello recordings.

After we turned Vogel down, Dieter Meier contacted me to audition for our tracks. We already had Death Cat, IT Splash, and Bostich ready. He sang a demo version of IT Splash with the lyrics “To the other, to the other, bar to bar,” and so on. I thought this staccato singing/rap was pretty cool, but Boris was rather averse to it; he preferred a female singer.

Dieter was a shouter for Fresh Color and had already released a single, ‘Cry for Fame’. One afternoon, we met for dinner on Langstrasse, Zurich. The result was that I moved my studio into Dieter Meier’s atelier. He already had a 4-track machine there. We continued to develop as Tranceonic.

At the end of 1978, we played a gig at the Cinema Forum for a fashion show. They called Boris and me “the synthesizer guys,” and Meier sang on the track ‘Death Cat’. Swiss television even filmed it. This ultimately led to the formation of the trio Yello. For those interested, I can recommend Jonas Warstad’s book The Yello Chronicles 1976–1984, available as a paperback on Amazon or digitally on Kindle.

Yello’s sound was, in many ways, an extension of the studio itself. It was a space of experiment where machinery became an instrument. Can you describe your relationship with the early synthesizers, samplers, and sequencers you used? Did you approach them as a traditional musician would an instrument, or more like a scientist in a laboratory, experimenting with a new form of matter? How did the limitations of the technology at the time force you into creative solutions that ultimately became part of your signature sound?

The approach with the instruments at that time was unorthodox. What mattered was experimentation, even more so for me than for Boris. Every sound discovered through research and endless experimentation was meticulously copied onto paper masks so they could be reactivated at any time. I had an entire folder of them from the ARP Odyssey, Quadra, and ARP 2600. These collections gave rise to the pieces in the pre-‘Fairlight’ and sampler phase. Since we were never traditional musicians or composers, only experimentation and imagination came into play, and that seems to be the secret of our success.

“A unique symbiosis developed in Yello”

The work of Yello, particularly in its early stages, has often been described as having a surrealist or Dadaist quality, a kind of absurdism. Was this a conscious influence? Were you inspired by artists like Salvador Dalí or Marcel Duchamp, or movements like Fluxus? How did you translate the principles of these avant-garde movements into a musical language? Was the “surprise” element in your music, the unexpected sound, the random sample, a deliberate homage to the surrealists’ fascination with the subconscious and chance?

Not really. Sure, I have a huge collection of art books and I know my way around. Dieter was still doing performance art back then, which I really liked, so a unique symbiosis developed in Yello. We had body, mind, and imagination. The press later pigeonholed us into these art movements. Sure, Dadaism was invented in Zurich, sure, I think Dalí is great, but Fluxus not so much. We simply produced music uninfluenced by the mainstream, something of our own. In Zurich, we were seen as outsiders anyway. Most people were still doing punk back then. Synthesizers were frowned upon and considered crap. Later, when we became successful and well-known, punks came to me in the studio and suddenly wanted to make electronic-oriented music. But that usually ended up being show nonsense.

Unlike many of your contemporaries, Yello’s music didn’t always conform to the verse-chorus-bridge model. Instead, it felt like a series of sonic vignettes, each a self-contained story or fragment of a larger one. How did you approach the composition process? Did you think in terms of a narrative, a visual scene, or a specific mood when building a track? How did you construct these “sonic architectures” that felt both abstract and evocative?

When Yello was founded, there were probably over two hours of pre-produced music. It wasn’t like we were just making a piece yx. For example, Bostich — I got the name simply because the trigger or sequence sounds like an office Bostich. Actually, the correct spelling is “Bostitch,” made in the USA. When we went to Platinum Studio, we took our 8-track machine with us and recorded Bostich onto 24-track tape. The track was edited and basically made ready for vocals. I called Dieter and said he could sing on Bostich. He then came into the studio with his lyrics and celebrated his spoken word (rap) with Bostich.

In short, the pieces of music were always created beforehand, and in the pieces where Dieter was allowed to sing, he wrote his lyrics, which he then recited to us and asked whether we thought what he had written was cool. The stories usually tell of a lonely guy who runs from bar to bar, longing for love, or of a woman who stars in a film noir, or what is “Dadaistique,” the Mulelle singing.

In much of your work, particularly from the Yello era, the pauses and the silence between sounds are as important as the sounds themselves. The sudden absence of a beat or a sample creates a palpable tension. Could you discuss your philosophy of silence in music? How did you use negative space to shape the listener’s experience and to create a sense of drama or anticipation?

For me, even as a Wagner fan, such an approach is somehow normal. The same was true back then with Yello when we were still a trio. It’s not like you said, “a negative space”; that can or must also be positive. As a teenager, I was impressed by the Beatles’ sometimes long, eccentric endings. Or, upon first hearing them, by the cool middle sections. It wasn’t just verses and choruses carelessly pieced together, but rather surprising and full of tension. Therefore, for me, as a modern-day music creator, it’s normal to generate such tension. I simply think it’s down to the imagination or lack of ideas of certain composers or producers, or a lack of humor. Although my sense of humor is rather dark.

The rhythms in Yello’s music were often a complex mix of percussive sounds, found samples, and programmed beats. They were highly danceable, but they also felt detached, almost mechanical. What was your relationship with rhythm? Did you see it as a functional element for dance, or as a more abstract, almost mathematical construct? How did you build these rhythmic landscapes that felt both humanly groovy and machine-like in their precision?

Carlos: Yes, machine-like but with a human feel. Not static, say Kraftwerk-wise. Definitely one of our strengths. There is nothing more boring than uninspired drums and percussion. So when a new piece was generated, the basic rhythm was the most important thing, it’s the skeleton. Once that was established, then let’s say the gimmicks come, that is, the flesh and muscles. These sounds are carefully selected.

Over time, we had two studios in the Rote Fabrik, Zurich, one for me and one for Boris. Dieter was writing his script for ‘Jetzt und Alles’ when he wasn’t singing. So everyone developed things, and we visited each other to listen to what we had produced and to comment on things like what could be added here, was there too much, etc. The aim was to keep it danceable, especially with Yello. With my solo work I was more abstract back then. But groove is the ruler.

In Yello, the vocals of Dieter Meier and Boris Blank’s spoken parts were often treated as another instrument, a texture rather than a lyrical centerpiece. How did you approach the integration of the human voice into your electronic compositions? Did you see the voice as a human counterpoint to the machine, or as a raw sound to be manipulated and processed like any other? How did this approach evolve over time?

In several Yello songs, Boris provided a kind of guideline with his voice. For example, in ‘Eternal Legs.’ In Tranceonic, it’s ‘Butterfly.’ He had a so-called “Roy Black” voice, and we both could imitate voices. If Boris and I had taken vocal training, we certainly would have become great singers too. But “shoemaker, stick to your last.”

Sometimes Dieter’s singing skills were exhausted, and we took over. Or later, guest singers. For example, on ‘Say Yes to Another Excess,’ I sang the Hohpps. The Eventide harmonizer played and continued to play a major role, first used by Dieter on ‘Bimbo’ on ‘Solid Pleasure’. Later, the very distinctive ‘Oh Yeah’ became a worldwide hit.

After our maxi-album on Periphry Perfume Records, the first proper single ‘Bimbo’ was released on Ralph Records, San Francisco. An absolutely underrated single. The fact is, without harmonizing, you wouldn’t have a typical Meier voice.

Visual aesthetic, from the album art to the music videos, was as distinctive as its sound. It was often a playful, slick, and slightly absurd world of its own. How integral was this visual dimension to the music? Did the visual concepts arise from the music, or were they developed in parallel? How did the two media, sound and image, inform and influence each other?

I wrote the first script for a Yello video. The idea was to film the exit and entrance of a factory for 10 hours. These 10 hours were then to be condensed into 20 minutes in time-lapse. I presented this in a creative session. Boris was enthusiastic, Dieter dismissed it, saying it would be far too expensive.

Well, I had suggested that we should make music films, since the music also had a certain cinematic touch. A few days later, we watched Dieter’s experimental films. He filmed his grandparents sitting on chairs using stop-motion technology. The effect was terrific. The grandparents trembled due to the delays; it was a hallucinogenic LSD effect. I was thrilled too, and Boris. So we decided to produce our first video, ‘The Evenings Young,’ using this technique. I provided the makeup and props. Dieter got out his 16mm Beaulieu camera, and everything was shot on film.

This concept was preserved until the 1990s. Yello always needed videos. ‘Pinball Cha Cha’ can also be seen at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Looking back at your time with Yello, what do you consider to be your most significant contribution to the project? And conversely, what is the most important lesson or artistic principle you carried with you from that era into your solo work?

Yes, without all my equipment and my acquaintance with Boris, Yello would probably never have existed. And without the development with Tranceonic, just as little. So this so-called contribution is significant. Regardless of that, during my time as a member of Yello, it was the unexpected, the spice of it all. Even back then, I was considered exotic and unclassifiable.

Since I released my first solo album ‘Impersonator’ in 1981 on the Konkurrenz/Phonogram label, I was always keen on doing solo work without the constraints of a band. I started with

‘Impersonator’ in 1978 in the first studio, inspired by Suicide. The success of the film Die schwarze Spinne enabled me to buy an even bigger studio and become independent from everything else.

You’ve explored a wide spectrum of sounds throughout your career. What drew you to industrial metal at this point in your artistic journey? Was it a conscious return to a more primitive, aggressive sonic palette, or was there a more specific inspiration? What new creative possibilities does this genre offer you that you didn’t find in your previous work?

I was already making what I called disco metal in 1984 with ‘Commando,’ with Chico Hablas on guitar. It was actually EBM/metal, and it fit the video I was allowed to cut from the film. ‘Gold for Iron’ also features a vicious metal track called ‘The Thrash’. Chico Hablas also played guitar.

Later, around 1994, I met Man Curtz, a brilliant guitarist. With him, I started the Dark Ruler project, producing a kind of industrial metal. Bone-hard and low-slung guitars, everything pre-Rammstein. Every few years, I come across metal geniuses like Stefan Bahners, and it was time to dig deep into the metal box and push the controls even higher until the windows burst. What an euphoric feeling and a shiver of goosebumps for those who understand it.

Finally, having been a pioneer in electronic music and now exploring a new genre, where do you see the future of music going? With the rise of AI in music production and the proliferation of accessible technology, what new frontiers do you hope to see explored? What is the one thing, a sound, a concept, or a technology, that you are most excited to experiment with in the future?

Yes, good question. I’m at the forefront of technological development. Depending on the workload, I play in every genre there is, or even invent them. Having my own labels has long since made me independent of boring major labels. Sure, I occasionally work for major labels, but only for a fee. Being independent is much more exciting, and I often turn a blind eye to that and do something for free.

As far as equipment goes, I’ve long since parted ways with synthesizer towers and crackling patch panels. I did my first fully digital production in 1991 with Yamaha equipment and a beta version of Steinberg. These days, I work exclusively with Mac computers with terabytes of samples and, of course, with AI. Of course, mastering also falls under this category (see liquidgoldmastering.de).

I’m currently preparing two shows: The Return of Terminatrix and my show at the OMBRA Festival in Barcelona. I develop new, hot, and cool tracks every day. I’m looking forward to the next stage: quantum computers and 32-bit hi-res in streaming.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Carlos Perón and Boris Blank at Tranceonic Studio (courtesy of the EISENBERG archive, used with permission)

Carlos Perón Facebook / Instagram / YouTube / Bandcamp