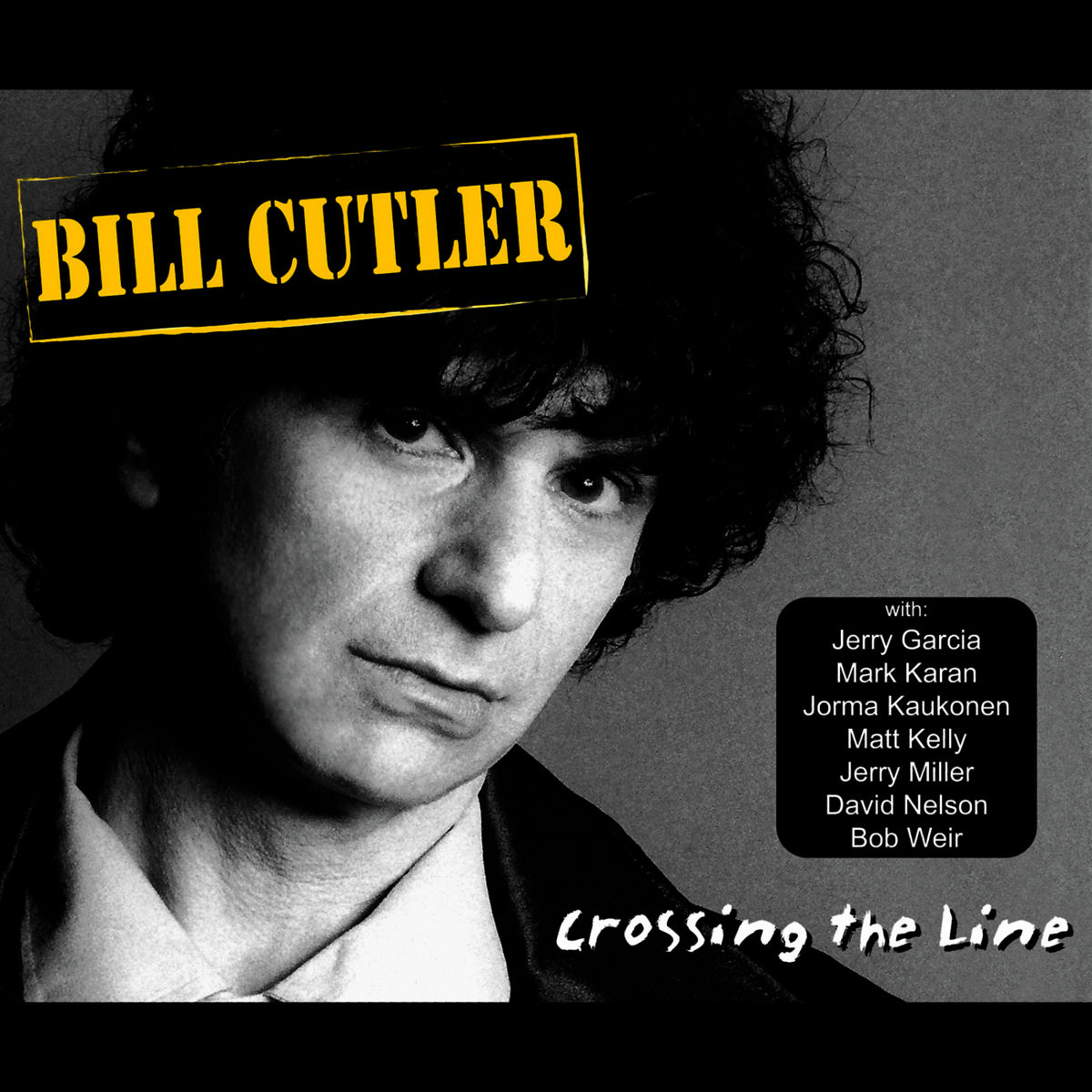

Crossing the Line: Bill Cutler’s Journey Through Greenwich Village Folk, Psych-Rock, and Punk

Bill Cutler is an American musician, songwriter, and producer whose career is defined by its continuous, agile crossing of key countercultural movements, from the Greenwich Village folk revival to the punk explosion.

Cutler’s musical roots were established in the highly charged Greenwich Village folk scene of the early 1960s. Sharing places with emerging talents such as Phil Ochs and David Blue, he absorbed the protest-song ethos that drove a significant cultural revolution. This acoustic focus evolved rapidly when Cutler was drawn to the electric energy of the San Francisco psych rock scene during the “Summer of Love.”

This evolution initiated his profound and long-running association with the Grateful Dead orbit. He is particularly recognized for his close, collaborative friendship with Jerry Garcia, who performed on Cutler’s acclaimed solo album, ‘Crossing the Line.’ A remarkable project, the album took 33 years to complete and ultimately featured an all-star cast of Bay Area rock legends. Cutler’s restlessness saw him plunge from the jam-band world into the fiery energy of the late 70s punk explosion with his band the Nu-Models. Beyond his work as a performing artist, Cutler established himself as a versatile producer. He was instrumental in restoring and compiling albums for the San Francisco punk label CD Presents—a catalogue that included seminal bands such as the Minutemen and Dead Kennedys. Later, his commitment to embracing new musical forms was underscored by his production work on a groundbreaking hip-hop version of Bob Dylan’s ‘Like a Rolling Stone.’ Cutler’s discography and production credits serve as a unique timeline, charting the major shifts in American popular music across five decades.

“Big talent collaborates, and small talent fears collaboration.”

From the protest-folk scene of Greenwich Village to the mind-melting “Summer of Love” and then right into the punk rock explosion of the Bay Area, you’ve been part of so many moments. It’s a wild ride, and we’ve got a bunch of questions buzzing in our heads. So let’s get right to it. Jumping right back to the beginning, what was it like being in Greenwich Village in the ‘60s, sharing the stage with guys like Phil Ochs and David Blue? That’s some seriously hallowed ground. Were you all just a bunch of kids with guitars, trying to change the world, or was there a sense of something happening—a palpable cultural shift you could feel in the air?

Bill Cutler: I first started playing in Greenwich Village in 1963, just as folk music was catching fire with a whole new generation. Rock n’ roll radio, which made Elvis, Buddy Holly, Ricky Nelson, and so many others huge pop stars in the 1950s, had gotten very stale in the pre-Beatles era, and many of us were looking for something more exciting. Bob Dylan’s first album had been out for about a year, and a group of young songwriters, including Phil Ochs, Eric Andersen, Laura Nyro, Patrick Sky, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Tom Paxton, and David Blue, were all mixing traditional chord structures with contemporary lyrics and social commentary to create their own genre. I really wanted to be part of that movement, so I began performing my songs on open mic nights at the Gaslight Cafe and other coffeehouses, trying to get my foot in the door. The Village was the perfect training ground for me, and over the next few years, I got to know musicians who were playing that same circuit and started opening shows for some of them.

It was the beginning of a cultural revolution that redefined folk singers as singer-songwriters and would eventually lead to the birth of folk rock.

At the same time as I was playing those live gigs, I was also pushing my songs at the Brill Building, where many successful publishing companies had their offices in Manhattan. One of my protest songs, ‘The Ballad of Catherine Genovese,’ about a woman who was stabbed to death in Queens while 38 of her neighbors heard her screams and failed to call the police, caught the ear of Paul Leka, a talented record producer who later went on to great success working with The Left Banke, Harry Chapin, Kris Kristofferson, The Lemon Pipers, and many other artists. Paul took me into the recording studio for the first time and offered me a publishing contract. I was still under 18, and my parents refused to let me sign the deal, insisting that I go to college when I graduated high school in the fall of ’64. But the combination of playing all those shows in the Village and working with Paul in the studio gave me the confidence to keep developing as a songwriter.

You went from acoustic protest songs to electric guitar and the Haight-Ashbury scene for the “Summer of Love.” That’s a massive sonic and cultural leap. What was the catalyst for that change? Did it feel like a betrayal of your folk roots, or was it a natural evolution—a new way to express the same passion?

In 1967, while I was still a college student at UConn, I started hearing all these great albums by psychedelic rock bands like Jefferson Airplane, Moby Grape, and the Grateful Dead coming out of San Francisco. I was immediately drawn to the power of that music, with amazing vocals and electric guitars, and I decided to drop out of school, drive across the country, and explore the Haight-Ashbury music scene. I spent three months in California for the “Summer of Love,” in both the Bay Area and L.A., and was completely taken by the friendly vibe, the rock ballroom scene, and the sense of limitless possibilities for aspiring musicians. Since I had no way to support myself out here, I wound up going back to the East Coast, but with a whole new understanding of how vital and rebellious rock music could be—and knowing I wanted to move to the West Coast.

I came to San Francisco again in the summer of ’68, and on that trip, I met Jerry Garcia for the first time when he was playing with an early version of the Garcia Band at The Matrix, a rock venue in the city. Impacted by all the incredible music I experienced in my journeys to California, I began learning to play electric guitar and put together my first rock bands. After going to Woodstock, I moved out to San Francisco, and it’s been my home base since then. For me, playing rock and switching from acoustic to electric guitar was a natural evolution, and I never felt any conflict with my folk roots. It was simply the next phase of my development as an artist.

The Slewfoot album co-produced by Bob Weir, with an all-star cast including Garcia-Dead family members—that’s a dream lineup for so many. What’s one memory from those sessions that really sticks with you? Was it a free-for-all jam session, or was there a more structured “get this song done” kind of vibe?

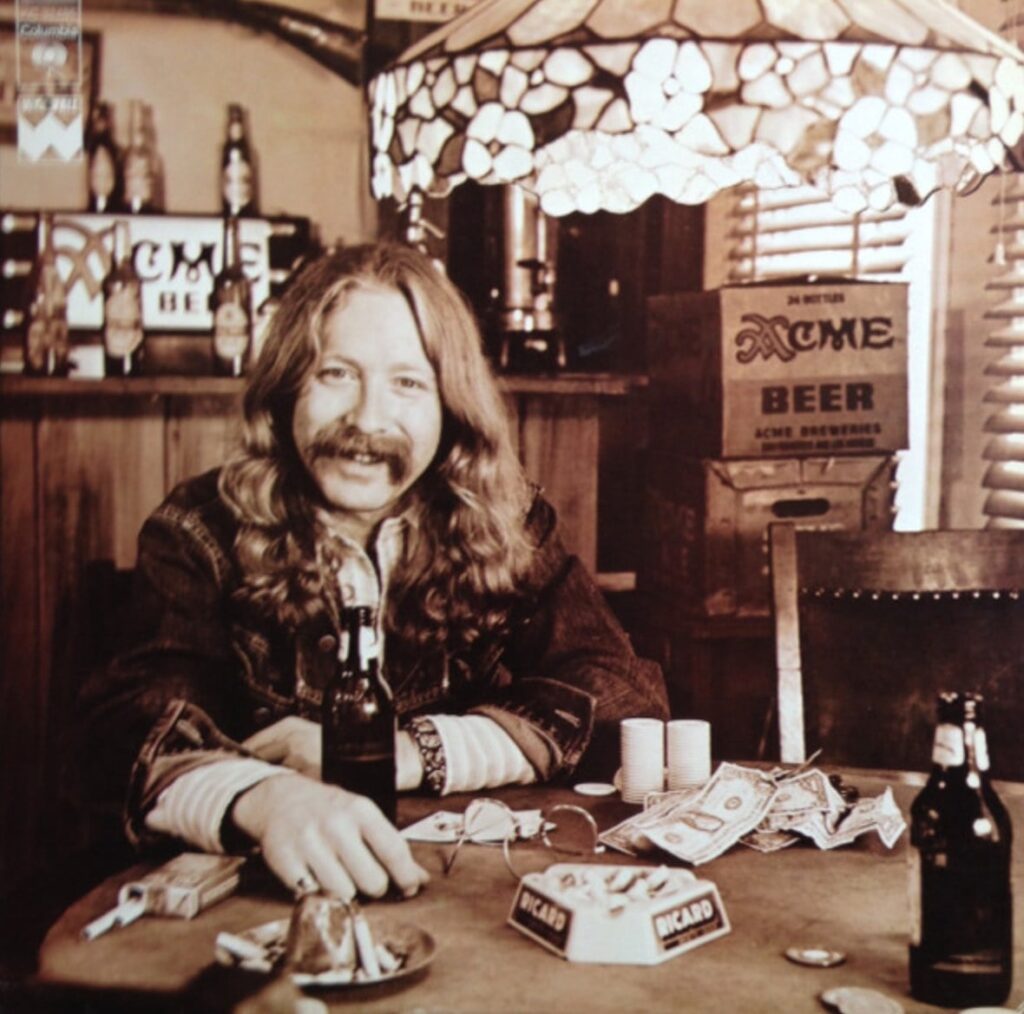

Bill Cutler: Well, I have many memories of David Rea & Slewfoot. Those sessions were structured around the songs, not jam sessions, but they were also chaotic, with so many different musicians involved in the tracking. One day you would get to the studio and find Keith Godchaux on piano, Spencer Dryden on drums, Charles Lloyd on a horn part, and on the next day, a whole new cast of stellar players would be there. I played rhythm guitar and sang some backup vocals, and that was my first exposure to the Marin County music scene.

One of the best memories I have from that time is not about any specific session but how I wound up in David’s band. After moving out west, I needed a new demo tape of my rock songs. I made one with some local musicians that was recorded by Steve Barncard, a brilliant engineer who had worked on American Beauty for the Grateful Dead. Nothing much came of that tape until one day, out of the blue, I got a phone call from David Rea, whom I had never met and never even heard of before. He told me he was a singer-songwriter and lead guitarist from Canada who had co-written the hit song ‘Mississippi Queen’ with Leslie West from Mountain and, based on that success, had been signed by Clive Davis to his own record deal. He was now living in Northern California, making his first solo album for CBS at The Record Plant in Sausalito.

David said Steve Barncard, who was engineering for him, had given my demo tape to Bob Weir, and Bob had passed it along to David. David liked my voice and a few of my songs and asked if I would be interested in coming in to play on some sessions. I couldn’t believe my luck. I had been out of work for months and suddenly had this amazing opportunity to play on an album.

When we were close to finishing his record, David needed to put together a touring band and asked me to be his rhythm guitarist. The new band, dubbed David Rea & Slewfoot, played our first show at the CBS Record Convention in San Francisco, on the same bill with The Sons of Champlin, Copperhead, and other major Columbia artists. The album was released, and everything was going pretty well for us until a few weeks after that convention, when Clive Davis was suddenly fired as president of Columbia Records. The new regime at the label immediately dropped all of Clive’s recent signings, including The Sons, Copperhead, and Slewfoot. So after a wild ride that lasted less than a year, I was out of a gig and starting all over again. But from my time in Slewfoot, I got to know a lot of great musicians I could call on for future projects.

“Jerry Garcia was the most generous musician I’ve ever known. He made everything magic.”

We’ve all heard about the legendary Garcia-Cutler collaborations, especially those “historic tapes” with Heroes. Can you talk about the creative dynamic between you and Jerry? What was it like watching him build a lead guitar part on one of your songs? Was it a conversation, or was it just magic?

Jerry was the most generous musician I’ve ever known. He made everything magic. The first time we worked together was in 1973, when he agreed to play lead guitar on my song ‘Ridin’ High,’ which was being recorded for Matthew Kelly’s album ‘A Wing and a Prayer’. The session was called for noon and both Jerry and I arrived on time, but none of the other players showed up for another hour and a half. Jerry asked me to play him my song so he could get familiar with the chord changes before the others arrived. I took out my Martin and started singing and playing the song. Jerry listened to the first verse and chorus and then asked me what kind of electric guitar feel I envisioned for this track. I told him I was looking for backstrokes to add a kind of Steve Cropper rhythm to the groove. Jerry smiled and said, “Man, I love Steve Cropper. He’s great!” And that was it. He turned up his amp and started playing a perfect rhythm guitar part. Then he asked me if he was going to get a solo, and I said, “Of course, you’ve got a long solo on the entire ride out.” By the second run-through with just the two of us, Jerry had learned all the changes to ‘Ridin’ High,’ added beautiful melodic licks that complemented my vocals in each of the verses, and played an incredible improvised solo for the ride-out section. For the next hour, we kept playing the song over and over, and each time he would continue to embellish his part with new and exciting ideas. By the time all the other guys arrived for the session, Jerry knew the song inside out, and every take he did was wonderful. The hard part was picking one as the master because they were all so good.

Over the years, our relationship remained just as positive as the first time we met. Whenever we played together in the studio, he was open to experimenting or just fitting in as a brilliant sideman. He always cared about getting things right. At the session for my album Crossing the Line, Jerry brought two different guitars with him: Wolf and his brand-new Travis Bean, and depending on the song, he switched between them to get just the sound he wanted. But his playing style was so iconic that it hardly mattered which guitar he chose, because both sounded incredible. I’ve met and worked with many great singers, songwriters, and musicians, but I’ve never known anyone else like Jerry. He was one in a million.

The sudden death of Craig Paulson seems like it must have been an absolutely devastating blow to Heroes. We can only imagine how difficult it was. Did you ever consider trying to keep the band going, or did his loss simply make it impossible to continue?

Unfortunately, Craig Paulson’s death was not the first tragedy we experienced in Heroes. When the band came together in 1974, our original lead guitarist was Scotty Quik, a groundbreaking player with his own unique style, experimenting with distortion pedals and other cutting-edge technology of the era. In the Bay Area, Scotty was quickly making a name for himself as an up-and-coming rock musician. He and I were good friends and we worked very well together.

About a year into the band’s existence, just as Heroes was starting to gain a local following, Sammy Hagar, who had recently left Montrose to become a solo artist, stopped by one of our rehearsals. He stayed for about an hour and said he really liked our band. The next day, Sammy called Scotty and offered him the chance to play lead guitar on his first solo album, which was about to go into production, but only if he was willing to quit Heroes. Scotty agreed to leave our band and went on to become Sammy’s lead guitarist on his debut album and in his live touring band. We were blindsided by the loss of Scotty and had to find a new lead guitarist immediately. Luckily, our keyboard player, Barry Flast, knew a terrific guitarist from Texas named Michael O’Neil, and we brought him into the band. Michael had a strong grounding in roots rock, and he was a great singer, giving us a shot of new energy just when we needed it most. With our new lineup, Heroes continued to develop, playing better shows at bigger venues.

At the same time, after finishing recording Sammy’s new album, Scotty Quik was going through a very rough period of his own. He had been doing hard drugs a few years before joining Heroes but had cleaned up entirely and was on top of his game when he was with us. But the pressure of being in Sammy’s orbit started taking a toll on him. Scotty felt he was not being treated fairly and began slipping back into drug use. He wanted to express himself as an artist but never felt fully accepted by the people around him. His isolation continued to grow, and several months later, very depressed, Scotty overdosed on a deadly cocktail of speed and heroin. He was only in his mid-twenties, and his death was a shocking event in the Bay Area music community. Like so many other rock artists—Jimi Hendrix, Kurt Cobain, Janis Joplin—Scotty’s life was cut short by drugs. He was a great talent, and it was a huge loss.

Heroes continued to play for another year until Michael O’Neil and a few other members were poached by bigger artists to join their bands, and once again I found myself needing a whole new group of players to continue. After searching long and hard for the right musicians, I found some terrific bandmates: Steve LeGassick on keyboards, Larry Hunter on bass, Craig Paulson on lead guitar, and Chris Herold, who had previously been the drummer in Kingfish. The five of us came together as the next version of Heroes. There was great chemistry between us and I loved the new band.

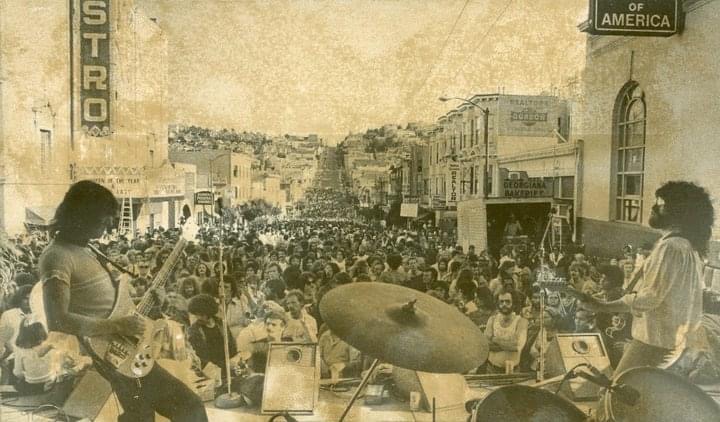

In 1977, Heroes headlined the Castro Street Fair, were playing shows with Moby Grape and the New Riders, and doing well enough to be booked as one of the headline acts for the very first Haight-Ashbury Street Fair, scheduled for April of 1978. That’s when Craig, who had been feeling ill, was suddenly diagnosed with liver cancer. He insisted that he wanted to keep playing with us, so we kept doing gigs with him until he became too weak to perform. There were no effective treatments or transplants for liver cancer in those days, and in a matter of months Craig died. I was about to cancel our upcoming appearance at the Haight-Ashbury Street Fair when Jerry Miller, the lead guitarist for Moby Grape, who had become a good friend of our band, contacted us and offered to sit in with Heroes so we could play the Haight Street Fair. We were thrilled to have him, and the set we played together on April 30, 1978, in front of a crowd of 100,000, was a thrilling experience. But it was also Heroes’ final show. After losing both Scotty and Craig, we were simply too emotionally exhausted to go on, and the band broke up.

From the Grateful Dead orbit, you plunged headfirst into the punk explosion with the Nu-Models. That’s a huge stylistic shift. What was the appeal of punk rock for you at that time? Was it a reaction to something, a new energy you had to tap into, or just another stop on your musical journey?

Bill Cutler: When punk rock and new wave hit the Bay Area, I was excited by the passion and intensity of these wild new bands. I started going to shows and getting to know that scene. Then I saw the first gig by The Clash in San Francisco and loved their songs, their political stance, and the sheer power of their performance. At that show, I was sitting next to Jack Casady, the bass player from Jefferson Airplane and Hot Tuna, and I asked Jack how he would describe them. He said, “It’s like the first time I saw The Who. Nothing will ever be the same again.” That was a perfect description. They were truly revolutionary.

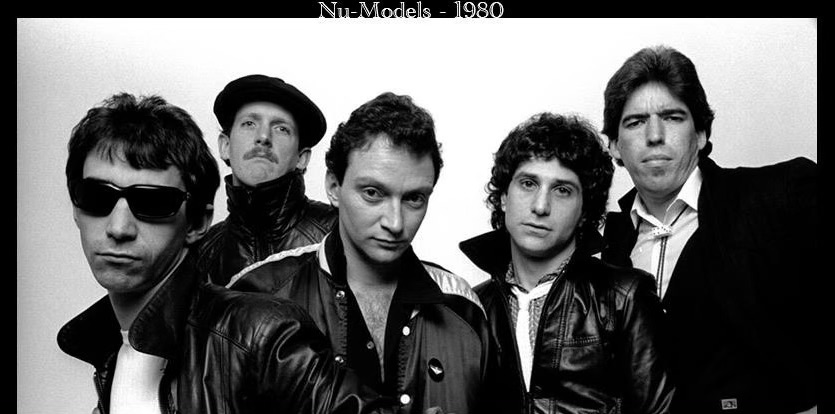

The next day, I began thinking about forming a new band and started co-writing songs with Steve LeGassick, the keyboard player from Heroes, who also wanted to explore this new genre. Steve and I cut a few demos of our songs down in L.A., and then returned to San Francisco and hooked up with a new group of like-minded players: Joe Stuart, a singer, songwriter, and lead guitarist; Michael Weinstein, a terrific bass player; and Kenney Dale Johnson, a wonderful drummer. Joe, Steve, and I shared lead vocals, and Michael and Kenney were a powerhouse rhythm section. Since it was a complete reinvention of our musical style, I called our band the Nu-Models.

Nu-Models quickly gained traction at all the punk and new wave clubs in the Bay Area, including The Fab Mab, The Palms, The Stone, and The Back Dor, and soon started playing shows in L.A. at Madame Wong’s, Club 88, and all the other punk venues on that circuit. The band was on fire and our songs were catching on with audiences. Our manager, Rodney Fowler, was a Rastafarian pot dealer who loved our music, and for the next year and a half, Nu-Models were on a steady climb, sharing bills with the Jim Carroll Band, Romeo Void, SVT, The Humans, The Lloyds, The Contractions, Chrome Dinette, and many others. Everything was going well for us, and several record labels were considering signing our band when Joe Stuart fell into drug addiction, causing a huge rift in the group. Joe was amazingly talented and had written a song called ‘She’s a Heart Attack’ that was one of our best, but he was also very insecure, and when we started having high-pressure showcases in L.A., he slipped back into doing drugs. We all tried to help him, but for me, it was like watching Scotty’s decline all over again. When it became clear that Joe was not going to change his ways, it put an end to Nu-Models. It took me a long time to recover my mojo after that experience.

Over the years, I lost touch with Joe, but Steve, Kenney, Michael, and I all went on to many other musical adventures. Steve and Brian Ray, who plays bass and rhythm guitar in Paul McCartney’s band, co-wrote the hit song ‘One Heartbeat’ for Smokey Robinson. Michael played bass with a number of great bands in both California and Florida. Kenney became the drummer in Chris Isaak’s band, and I started producing albums for many artists and co-writing songs with guitarist Robbie Dunbar from the East Bay band Earthquake. Together we formed my next band, Lost Souls, in 1981. Heroes had cemented my place in the jam band world, but Nu-Models gave me a whole new following that sustained my career for years to come.

You worked with Bob Dylan on the Mystery Tramps’ track ‘Like a Rolling Stone,’ even getting to sample his iconic voice. We’re dying to know: did you have any direct interaction with Dylan himself about it? What was it like getting his blessing on such a unique, genre-bending project?

I had been seeing Bob Dylan perform since the 60s in Greenwich Village, and I had spoken to him a few times in the early days at The Gaslight, but I didn’t really know him well. I went to a number of his gigs, including his first full electric show at Forest Hills Stadium in the summer of 1965, right after Newport, when “Like A Rolling Stone” was at the top of the charts. Even though the crowd booed the electric band from the moment they took the stage, I loved that show and I knew I was witnessing something historic that night. I also took my younger brother John with me to that show, and after seeing the concert, John decided he too wanted to go into music. John started out as Heroes’ first soundman, then became the Jerry Garcia Band’s front-of-house mixer in the 1970s, went on to become a recording engineer, and in 1987, the co-producer with Jerry of the Grateful Dead’s biggest album “In the Dark,” which contained their hit “Touch of Grey.” The following year John also recorded the live ‘Dylan-Dead’ album. So my brother got to know Bob much better than me.

When I started hearing rappers covering rock artists in the 1990s, the idea of doing a hip hop version of ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ came to me. I partnered with a good friend of mine, Mark Myers, an engineer who was working with some of the best Bay Area rappers, and we created the Mystery Tramps to record our version of the song. I was not sure what Bob’s reaction to a rap cover of his most famous song would be, so once we had a rough version of the track, I called his publishing company, Special Rider Music, to ask if they thought he would be OK with it. To my great surprise, the guy who answered the phone at Bob’s publishing company turned out to be David Levin, who I had known years earlier when he was working in the mailroom at Atlantic Records. David had gone on to work with Tina Snow, who was running Bob’s publishing company. I could not have found a better person to work with me on this. David suggested that we send down a CD of the track and he would play it for Bob to get his reaction. A few weeks later David called and told me that Bob loved our version and was fine with us shopping it to labels. We were overjoyed. I then asked David if we could get a letter from them saying Bob was behind the project to help convince record companies to consider signing us. Tina Snow wrote us a beautiful letter of support and I gave the song and the letter to Stuart Wax, an LA manager, to start shopping the Mystery Tramps.

Nothing really happened with the project for over a year, so I assumed it was dead in the water. Then one day in 1992, I got a phone call from Ron Baldwin, an A&R rep at Imago Records in New York, saying he was interested in signing the Mystery Tramps and releasing our version of “Like A Rolling Stone” as a dance single on their label. We had done a radio mix, and Ron said he liked that but also wanted house remixes to be used in the clubs. I told him that was just fine with us. It was incredibly exciting to get this offer and I couldn’t wait to share the good news with Mark Myers and Michael Ehrlich, our executive producer who had paid for the recording. Then Ron said: “There’s just one thing I don’t understand. Why did you include this letter from the publisher saying Bob supports this project?” I explained that I wanted record labels to feel comfortable signing the Mystery Tramps and releasing a hip hop version of the song without any fear of legal complications. Ron said since we had not changed any of the original lyrics, there was no need to have permission to release it, as long as we paid Bob the publishing income from the single. Then Ron asked me what else I had hoped to get from Bob Dylan. That’s when I said, “I would love to have had a Dylan sample for our record.” Ron said, “Dylan sample? That’s brilliant. You get me that Dylan sample or there’s no deal.” At that moment I felt like a total idiot. A minute ago I had a record deal, and now it all depended on Dylan approving a sample, something Bob had never done in his entire career. In fact, Dylan had famously sued the Beastie Boys for using a sample of one of his songs on their album and received a huge settlement. Talk about snatching defeat from the jaws of victory.

The next day I called David Levin at the publishing company and told him what had happened. David said he doubted that Dylan would approve any sample but said if we put a new version together, using the exact sample we wanted and sent it to him, he would play it for Bob. So Mark and I sampled Bob’s voice singing “How does it feel?” from the chorus of the original recording and wove it into the soundscape of the verses. Since we had kept the song in the original key and at a similar tempo, it fit perfectly and added a beautiful texture to the track.

About a month later, David called me to say Bob had heard the new version and approved the sample. It was a mind-blowing moment. Not only did Bob approve the sample, but he also charged us very little to use it, to make sure we could afford to go through with our record deal. I couldn’t wait to call Ron Baldwin at Imago and tell him the good news. I called immediately and said: “Guess what, Ron? Bob just approved our sample of his voice on the track. Do we have a deal?” Ron’s reaction was not what I expected. Instead of congratulating me, he told me that we didn’t yet have the right to use the sample because Columbia Records owned the master recording of ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ and they too had to approve our use of Bob’s voice. I couldn’t believe it. After all this, there was still another huge hurdle before we could move ahead.

Nevertheless, Ron was right. We did need approval from Columbia as well as Dylan. Adding to the complexity of the situation was yet another big issue. Imago Records was distributed by BMG and Columbia was distributed by Sony. Those two giant companies were competitors, not partners, and Columbia did not want any BMG label making money with Bob Dylan’s voice. It took me months to even get in to see anyone at CBS, but eventually I did, and once I showed them our signed agreement for the use of the sample and Tina Snow’s letter of support, they reluctantly agreed to let us have it. But even after Columbia approved the sample, they still refused to give us access to the master tape, and the demo version of the song, using the sample we had taken from the vinyl recording, became our new master. Finally, in 1993, almost two years after we had started the project, the Mystery Tramps signed with Imago and our dance single was released. I thought that was the end of the problems we were facing, but I was wrong.

Once the single was released and Imago was sending out house mixes to the clubs, it sparked interest in the rock press. We got a terrific review in Billboard from Larry Flick, and I did a few short interviews with Vibe Magazine and the New York Post. Mark and I also began putting together a live version of Mystery Tramps. About a month later, I got a call from a woman I didn’t know at Imago who said she was from “the black department of the label,” informing me that they were about to release our single to mainstream radio and said, “Honey, it’s going to be a love muffin.” She told me Kurt Loder was covering Mystery Tramps that very night on MTV News. Kurt did do a story about us on MTV News. Unfortunately, the headline was: “Bob Dylan is sampled, and none too happy about it, more on MTV News.” Then Kurt did a brutal hit piece accusing the Mystery Tramps of stealing the sample and played only a few seconds of the record with the Dylan sample. He said MTV News had caught up with Bob while he was touring Europe and showed a clip of one of MTV’s reporters asking Dylan how the Mystery Tramps had gotten his voice on their new single. Bob said: “Beats me.” That was the entire report. Dylan is famous for putting on reporters and often gives evasive answers to questions he doesn’t like, but why Bob chose to respond that way I will never understand. Everyone involved with us, the label, our attorney, and radio promoters, all knew we had obtained the sample legally, but without any way to counteract this bad publicity, Imago immediately pulled our single from radio and we were devastated. Then they dropped us from their roster and that spelled the end of the Mystery Tramps.

You’ve had a hand in everything from producing albums by the Circle Jerks and Black Flag to working with pop artists like Jewel and managing a nu metal band, Spike 1000. How do you, as a producer, approach such wildly different artists? Is there a common thread in your process, or do you have to completely reset your brain for each project?

Well, just to be clear, I’ve produced albums by many punk bands, but I never worked directly with the Circle Jerks or Black Flag. I restored a huge catalog of live and studio recordings for the San Francisco punk label CD Presents that included albums by those two bands, as well as the Avengers, Minutemen, Bad Brains, Butthole Surfers, NOFX, TSOL, Corrosion of Conformity, Dead Kennedys, Flipper, Subhumans, D.O.A., Mojo Nixon, Tuxedo Moon, Adolescents, The Offs, the Sea Hags, and others. All those tapes had been stored under very poor conditions for many years and had to be baked in a special oven that restores analog tape, making it reusable for a short period of time. Working with Jeffrey Norman, the engineer who mixes and masters Grateful Dead vault releases, we were able to bake all the reels at their studio. Then I transferred all the music to a digital format at Norm Kerner’s Brilliant Studios in San Francisco, and in some cases I did remixes of the material as well. So I was the “restoration producer,” but not the original producer of any of those albums.

To answer your main question, yes, it’s always a major adjustment to go from producing one artist to another, especially when they’re in completely different genres. I approach every new project as a separate challenge. Some producers have one sound they are known for, but I don’t try to repeat the same techniques with every album. First, I spend time getting to know each new artist and asking them what they hope to achieve. Once I have a clear understanding of that, I suggest ways we can go about reaching their goal. I always go through a period of pre-production where we can throw around ideas before going into the studio, and I can get familiar with their music on a deeper level. So what I do with a rock artist like Paul Collins or a jam band like The Big Wu is very different from what I do with a nu metal band like Spike 1000. There are some things that never change, like having a great song gives you a much better chance of turning it into a great recording, but every artist has their own way of working. Some require a lot of creative input, and some arrive fully formed with a definite idea of who they are and what they want to sound like. One of the most important things I do is create the right environment for an artist to give a great performance. I take good ideas from everyone involved in the process because nothing is more exciting to me than watching a song develop from a rough idea into a beautiful piece of music.

Let’s talk about the unsung heroes of music. You’ve been part of so many different scenes and have seen so many artists come and go. Who was an artist or band that you worked with who you felt was absolutely brilliant but just didn’t get the recognition they deserved?

When you’ve made as many albums as I have, you’re going to feel like some of the artists you loved working with never achieved the level of success they deserve. Here’s a story about one of those situations. One of my first projects as a record producer, in 1981, was working with a Bay Area band called The Lloyds, a new wave group with a fabulous lead singer named Lulu Lewis. They wrote fantastic songs, exploded on the live scene, and quickly became a huge local success. Everyone had high expectations for The Lloyds, and I was very excited to work with them. We recorded a number of songs together that I thought sounded great, some of which were released on a local EP. The Lloyds appeared in the movie Die Laughing, were opening shows for major rock acts, and Lita Ford covered their song ‘Rock and Roll Made Me What I Am Today.’ But even though the band was continuing to get more and more popular and gaining rave reviews in the press, for some reason no record label ever wound up signing them. Like many other artists without a record deal in the mid-1980s, the band broke up. I’ve remained friends with everyone in The Lloyds and still think they were one of the best bands of their era.

Flashing ahead forty years, The Lloyds’ original bass player, Peter Heimlich, moved to Atlanta, Georgia, and one night happened to run into a guy who recognized him from his days in The Lloyds. He told Pete that he had lived in San Francisco many years ago, had seen The Lloyds perform, and loved the band. He assumed they had been signed to a label and asked about who owned the rights to their recordings. When he found out that no label had signed The Lloyds, he told Pete that he owned a small punk label called Projection Platters and would like to sign them and release a vinyl album of their material. Pete contacted me and asked where the master tapes were from all those years ago. Of course, the tracks were done in studios that were long gone, but David Martin, the band’s lead guitarist, went on an extensive search, located all the original mixes, and the label released a beautiful retrospective album called Let’s Go Lloyds! with terrific photos, graphics, and posters from the old days. It was gratifying to see a revival of some of my favorite music that had initially fallen through the cracks.

But that’s not the end of the story. The vinyl release got some great press, with praise for Lulu’s dynamic vocals and the band’s powerful sound. Months later, Arne Shorr, who runs a much larger reissue label called Liberation Hall, contacted The Lloyds and asked who owned the CD rights to all their material. When he learned that no one did, Arne decided he wanted to release a CD of The Lloyds and put together an incredible package containing all the songs on the vinyl release and a number of restored live tracks as well. That CD, called Attitude Check after one of the band’s most popular songs, came out and immediately took off. Over the last few years, The Lloyds have been featured on Little Steven’s Underground Garage, interviewed on major podcasts, discovered by new fans, and finally gotten the recognition they were denied in their heyday. So this is one story with a happy ending, but the music business has always been about success, not creative expression, and I can think of many deserving artists who never got a second chance.

You’ve come full circle with your own solo album ‘Crossing the Line,’ featuring all these legends you’ve worked with over the years. What was the motivation behind finally putting out your own record? Was it a culmination, a way of tying up loose ends, or a new beginning?

Making ‘Crossing the Line’ was the most difficult undertaking of my entire professional life. In 1975, when I decided to record an album of my own, I had been writing songs for many years, some of which had already appeared on albums by other artists, but outside of the Bay Area, I was still a relatively unknown singer-songwriter looking for the right way to present myself to the industry. I had a clear vision of how I wanted my music to sound, and I knew wonderful musicians, but almost everyone in my orbit was playing in a touring band and spending most of their time on the road.

I was also starting to put together the first version of Heroes, with Scotty Quik on lead guitar, Barry Flast on keys, Pat Campbell on bass, and Carl Tassi on drums, but our group had three prolific songwriters, so some of my best material was not going to make it into the band’s repertoire. I knew I needed to find another way to break through to a wider audience. My friendship with engineer Steve Barncard had grown over the last few years, and I asked him to work with me on this new project, using Heroes and some other good players to back me up on the album. We booked time at Wally Heider’s Studios in San Francisco for February of 1975 to start recording.

While I was getting ready to cut basic tracks, the Grateful Dead announced that they were going on an extended hiatus for the next year and would not be playing live shows for quite a while. At the session for Ridin’ High a few years earlier, Jerry Garcia had told me that if I ever made an album of my own, he would like to play on it. I didn’t really take that offer too seriously, but one night, several weeks before I was to start recording, I went to a Garcia Band gig at Keystone Berkeley. During the break between sets, Jerry approached me and said he had heard I was going to make an album of my own and asked if he was going to get to play on it.

I was stunned by his offer and said, “Of course I’d love to have you play on it, but I didn’t know you were going to be available, so I already have an entire band ready for those sessions.” Jerry asked who was on lead guitar and I told him it was Scotty Quik. Jerry didn’t know Scotty, but right away he said, “OK, how about having two lead guitarists on the tracks? We’ve got two drummers in the Dead and that works just fine.” I immediately said great, but we have a limited budget and I need to hold rehearsals so we can get this done in just a few sessions. Jerry said, “Let me know where and when and I’ll see you at rehearsal.”

We did several rehearsals with Jerry, Scotty, and me on guitars, Austin DeLone on piano, Pat Campbell on bass, and Carl Tassi on drums. Jerry and Scotty played beautifully together, and by the time we went into the studio, we sounded like a very tight band. We cut half an album in just one day. Jerry did fabulous solos on ‘Rockingham Mill’ and ‘Delta Nightingale.’ Scotty had prepared a melodic solo for my song ‘Slow Glider,’ and when Jerry heard it, he came up with a gorgeous harmony part that complemented it perfectly. When the two of them played that solo together, it was sheer magic. I still get chills hearing it to this day.

We all loved the tracks, and we intended to schedule more sessions for the second half of the album, but shortly after that, Jerry got involved with a number of other recording projects for the Grateful Dead’s new label, Round Records, and he was not going to be free for months. Jerry’s own band started touring as well, so there was no way to finish my record at the time.

Over the years, Jerry and I remained good friends. My brother John became one of his most trusted partners, working with both the Grateful Dead and Jerry’s band, but the tapes of my album remained unfinished, and I went on to play in other bands and produce many projects. In 1993, after I got the Mystery Tramps deal, I went to see a Jerry Garcia Band show at the Warfield Theater to give Jerry a copy of the dance single. That night Jerry asked me what had happened to the tapes from my album. I told him they had been sitting in my house for the last 18 years. He said, “Let’s restore those tapes, cut the other half, and finish your album.”

I loved the idea, so my brother and I baked those tapes at the Dead’s studio in San Rafael and transferred them to a digital format. Once we heard them again, they sounded great, but Jerry’s health went downhill before we got to work on the record again, and soon after that he was gone. Jerry’s death hit me very hard, and those tapes went back in the closet again. But a few years later, since these were some of Jerry’s only studio tracks outside of the Grateful Dead that were still unreleased, people wanted to hear them, and I decided to go back to work on my album.

In 1998, I went into the studio with many of the same players from the original sessions, who were now much more well known, and reached out to a number of my favorite lead guitarists who I had worked with in the past: Jerry Miller from Moby Grape, Jorma Kaukonen from Hot Tuna, Mark Karan from Ratdog, and David Nelson from the New Riders. I also worked with my old friend Pat Campbell on bass and Dave Perper, a terrific drummer who had been in both Heroes and Kingfish. I took new songs I had written in the same style as those from the original sessions and tracked everything in analog to get a similar sound. The new recordings were engineered by Gary Mankin and Russell Bond. Both of them did spectacular work. Russell also mixed the album with me. It was finally finished in 1999, and I was hoping to find a record label to release it on Jerry’s birthday in 2000.

It was then that the Garcia Estate got involved and everything changed. This was a period of time when there were still a series of lawsuits going on between Jerry’s relatives to determine who would ultimately have control of Jerry’s music catalog. I had paid Jerry along with everyone else on the original recordings, but I never signed a sideman agreement with him, since the album wasn’t finished when he was alive. Now that I wanted to release my album, suddenly that became an issue for the lawyers. This was my solo album. I had written all 14 songs. I sang all the lead vocals. I hired all the players and I had produced it myself. I never presented it as “a Jerry Garcia album,” but I wanted the right to use Jerry’s name, along with Bob Weir, Jerry Miller, Matthew Kelly, Mark Karan, and everyone else who was on my record.

For some reason, this set off a firestorm that lasted almost a decade. The Garcia Estate told me they had entered an agreement with Rhino to handle all of Jerry’s music, and the label considered this album part of that agreement. They told me I needed to contact Rhino and work with them on a release. So I contacted Rhino and sent them the record. They said it was a Bill Cutler album, not a Jerry Garcia project, and therefore they couldn’t release it, but neither could anyone else. By now every label was afraid of a lawsuit, and it took me years to prove this was my record.

Without going into all the absurd twists and turns, I finally got help from Debra Garcia, who had been at the original sessions for my album, and Tom Jorstad, who had assumed a new role at the Estate. Eventually, in 2008, I won the right to put out my own album, signed a contract with Magna Carta Records, and Crossing the Line was finally released 33 years after I started the project. Then, in another wild turn of events, the Grateful Dead decided they loved my album and started selling it on their website.

In spite of all that I went through to make this album, it’s still one of my proudest musical accomplishments. The experience taught me that there’s no expiration date on music and art. Last year I did a new rock video for the title track of my album with filmmaker Debra Knox.

That video won “Best Music Video of 2024” at the Paris Film Awards, New York Movie Awards, the International Gold Awards, and the Shanghai Indie International Film Festival, and it is currently in the running at this year’s Toronto International Film Festival. So Crossing the Line is the gift that keeps on giving, and I’m overwhelmed by the positive feedback I’ve received about it from people all over the world.

What’s the most important lesson you learned about the music business? The industry has changed so much; what’s the one thing you wish young musicians today knew?

The most important thing I’ve learned in the music business is to follow your instincts and only make music you believe in. Don’t ever compromise your vision for anyone else. There are also other truths I’ve discovered. One of them is that big talent collaborates, and small talent fears collaboration. Another is that the musician standing next to you on stage is a hell of a lot more important than you thought he was.

I guess the one thing I wish young musicians knew today was the magic of playing in real time as a band on recordings, not simply pasting your tracks together in Pro Tools. Technology is a wonderful tool, but I wish young songwriters wrote more complete songs with stronger melodies, memorable choruses, powerful lyrics, and inventive chord changes. Simply adding and subtracting elements on a song is no substitute for expressing real emotions or doing the hard work of developing an original sound that’s brave, new, and real. But there’s great talent in every generation, and I still find plenty of new artists who inspire me.

We’ve talked a lot about the past, but what’s next for you? Are there any new musical projects, collaborations, or a specific event that’s catching your ear and pulling you in right now?

My current recording project is producing Freddy Clarke and his band Wobbly World. They’re a collective of 15 musicians from different countries and varied backgrounds, who together make a unique world beat sound, singing in many languages, playing exotic instruments, and representing the positive aspects of immigration at a time when so many are demonizing those coming to America in search of a better life. Wobbly World are the subject of a new documentary film, and I’m working with them on the soundtrack.

I’m also considering an offer from my good friends The Big Wu, a wonderful jam band in Minneapolis, to make their next album over the winter. We’ve worked together before on several records, and their band has been together for over 30 years with a rabid following in the Midwest.

I’m lucky to still be in demand for new projects, and I’m still excited about writing and playing my own music as well.

Klemen Breznikar

Bill Cutler Website

I think it was 1967 Eugene Macarthy was running for president. He had a rally in Wilmette or Winnetka. I remember Phil Ochs was there playing his guitar. I took pictures of the event. I have the photos somewhere…I was 16 years old.

Bill cutler has been a great inspiration for me! I’ve worked with him on and off for the last 30 years. A great mentor and collaborator.