JAMBINAI: The Orchestral Extension of Post-Rock

JAMBINAI occupies a unique space between tradition and the future. This post-rock band, hailing from a country with a profound musical heritage, has built a sonic language with the geomungo, haegeum, and piri at its core.

It’s a language that speaks of ancient sorrow and modern fury, of tranquil beauty and post-rock catharsis. As they prepare to collaborate with the London Contemporary Orchestra, they are opening a new conversation, one that proves the most powerful music comes not from a single culture, but from the universal truths that echo between them. On October 5th, JAMBINAI will perform with the London Contemporary Orchestra at the Barbican, under the direction of conductor Robert Ames. This show marks the first time a traditional Korean band has headlined the Barbican. This orchestral collaboration represents a new evolution of their sound—blending cinematic textures with Korean folk aesthetics—and continues their long association with the K-Music Festival.

“We’ve treated the orchestral sound as an extension of post-rock.”

A lot of your music feels like it’s in conversation with something deeply rooted in Korean identity, but it’s delivered with this “modern” energy. Your work with the London Contemporary Orchestra feels like the ultimate manifestation of that. What kind of conversations have you been having with the orchestra’s conductor, Robert Ames, about how to bridge the two musical worlds, not just in terms of arrangement, but in spirit?

For now, we’ve sent our rearrangements of the songs to them and are waiting for their feedback. Even before the Barbican facilitated this collaboration, we had been very interested in working with them. They’ve collaborated with many artists we admire, and despite our band being relatively unfamiliar to the orchestra, they gladly agreed to work together. That alone showed us that they are truly people driven by pure curiosity and passion for music. As we begin to discuss more detailed aspects, I’m confident this will turn into a really enjoyable project.

I’m thinking about the Barbican setlist—songs like ‘Time of Extinction’ and ‘They Keep Silence’ have always felt so explosive. How do you translate that intense, almost visceral post-rock dynamic and energy to a full orchestra? Are you thinking about the orchestra as a massive extension of your sound, or more as a contrasting, textural element?

The orchestra has such a diverse tone, and I believe that allows for the creation of a wide range of music. For this project, we’ve treated the orchestral sound as an extension of post-rock. You’ll hear sections where we use extended techniques—non-traditional playing methods that produce powerful noise—as well as pieces built on more traditional harmonies.

Your music often explores the dualities of Korean culture—the beauty of tradition alongside the pressures of modernity, and a deep-seated sense of both ‘heung’ (joy) and ‘han’ (a complex, untranslatable feeling of sorrow and longing). When you’re composing or arranging a piece for an orchestra, how do you ensure that these unique, deeply Korean emotions still come through without being diluted by the classical setting?

Actually, the concepts of han and heung were introduced by a Japanese critic in reference to Joseon, which was Korea’s name before it became the Republic of Korea. I don’t think those emotions are unique to Koreans; sorrow and joy are universal feelings. With this project, we wanted to capture emotions that anyone, anywhere, could connect with.

The geomungo is a central pillar of your sound. Its percussive and melodic qualities are so unique. When you’re working with the LCO, how do you prevent the orchestra from simply overwhelming the geomungo? Is there a conscious effort to give it space, to let its deep, resonating voice still cut through the sonic landscape?

The geomungo has a short sustain, so it sometimes functions like a percussion instrument, whereas orchestral strings and winds have a long sustain. We’ve tried to make use of that contrast in the arrangements. Of course, the orchestra has a far greater number of instruments, so we need to control the dynamics carefully to make sure the single geomungo can still be heard. That balance is something we’ll find together through listening and adjusting in rehearsal.

Back when you were all studying at the Korea National University of Arts, you were already thinking about how to make traditional music relevant to a new generation. Now, with performances like the Winter Olympics and this upcoming Barbican show, you’re not just making it relevant…you’re making it a global phenomenon. Do you feel a sense of responsibility as ambassadors of Korean traditional music, or is the focus still on your personal, creative expression?

In the past, I thought of myself as an artist who was promoting Korean traditional instruments or music. But as time went on, I realized that wasn’t really the case. People enjoy JAMBINAI’s music, not just JAMBINAI’s instruments. And whenever outside intentions creep into music, it often doesn’t turn out well. So now, my focus is on personal creative expression above all else.

I know you’ve mentioned in the past how the Korean education system has stifled creativity, and that you’re inspired by musicians who ask “why?” and create their own sound. What does it mean to you to now be a role model for a new generation of Korean musicians who are seeing you find success by breaking those molds?

I’m not sure if I can really say that I’m anyone’s role model. But seeing many musicians creating their own music, that’s something that genuinely makes me happy.

Many of your tracks, particularly on albums like ‘ONDA’ and ‘A Hermitage,’ feel like they are telling a story or evoking a specific image. What can you tell us about the visual ideas that you’ve been exploring as you prepare for this large-scale performance? Is there a central theme that ties the Barbican set together?

When we work together as JAMBINAI, our first idea is always to make sure the drums, bass, and guitar don’t feel alien next to the traditional instruments. That way, the music feels alive and naturally tells its own story, allowing listeners to form their own images. This time, the key idea was to ensure JAMBINAI’s sound—that is, the traditional instruments—doesn’t feel out of place with the orchestra. Hopefully, the results will let the audience imagine their own images as well.

Let’s get into the nitty-gritty. What was the most challenging track to re-imagine for this orchestral collaboration, and why? Was there a specific moment in a track where the arrangement just clicked, where you knew you had found the perfect balance?

That would be ‘ONDA’. It’s the longest piece, so there was a lot to work on, but its narrative quality also made it a perfect match for the orchestra. In the final section, the more voices we have in the choir, the better—it’s such a powerful moment. There is a choir this time, but if we had the chance in the future, I’d love to see it performed with an even larger choir.

The title ‘ONDA’ can be translated as “come” or “wave,” and it’s a theme that seems to run through your work—the idea of a tide coming in, of something new arriving. This Barbican performance feels like another significant wave in your career. What do you see on the horizon after this? What’s the next wave for JAMBINAI?

The future never seems to turn out as you predicted. Of course, I dream that this orchestral project will be a success and that we’ll collaborate with even more people, but I can’t say for certain. All I can do is keep rowing forward, letting myself be carried by the waves of life. Sometimes that means rough seas, sometimes it means discovering beautiful islands, and right now it feels like we’ve docked briefly at the Barbican.

Lastly, a lot of our readers might be hearing about the haegeum or piri for the first time. For someone who is completely new to these instruments, can you describe the unique character or “personality” of each, and what they bring to your music that a standard rock instrument simply couldn’t?

The haegeum, a two-string bowed instrument, is capable of expressing a wide range of emotions. In JAMBINAI, it often takes on a vocal-like role. The piri, with its oboe-like timbre, combines a warm tone with a sharp, penetrating power. Both instruments can bend freely into microtones beyond fixed pitches, creating subtle tuning contrasts with standard rock instruments. That tension is central to what makes JAMBINAI’s sound so distinctive.

Klemen Breznikar

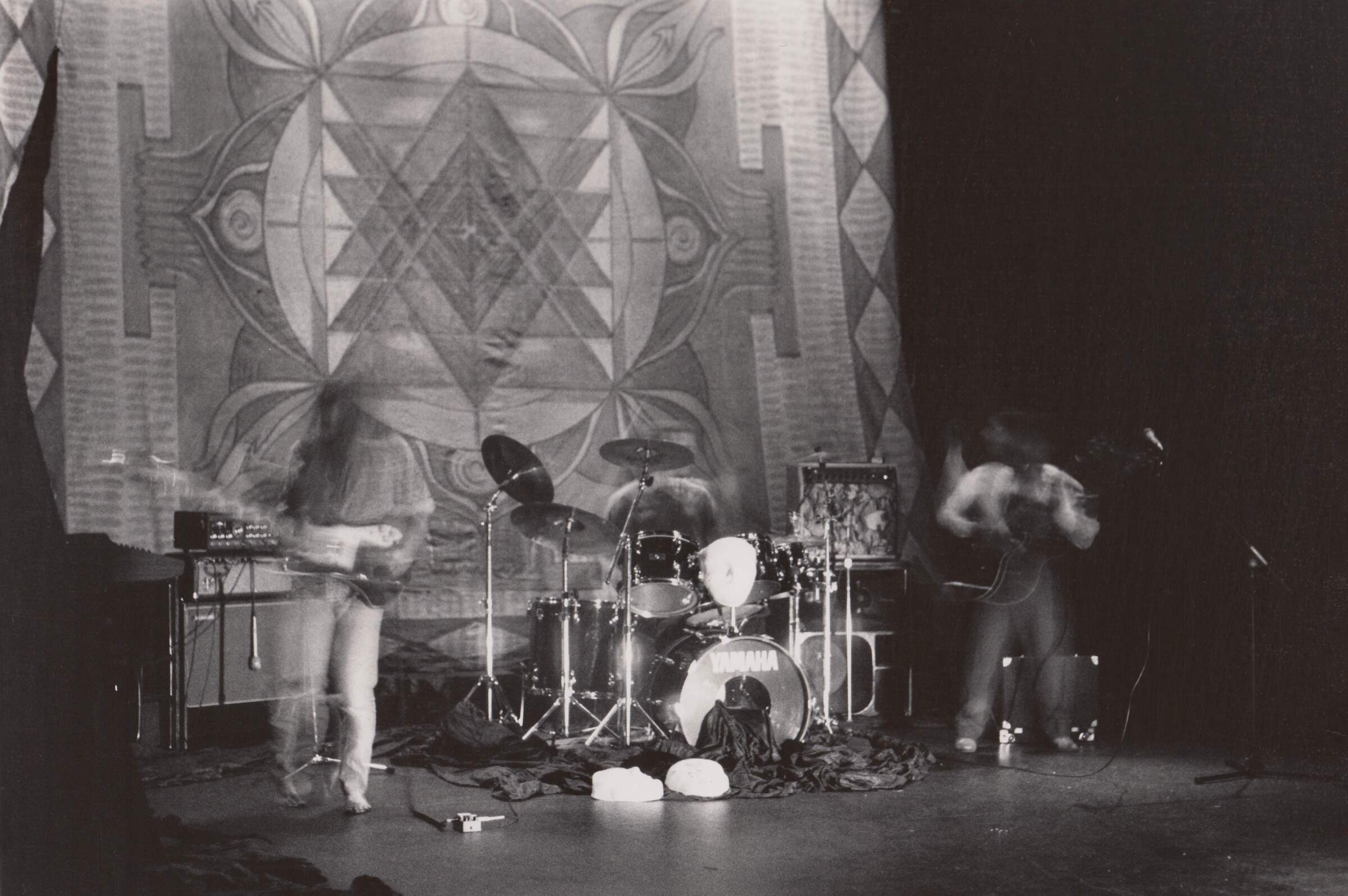

Headline photo: Shin-joong Kim

JAMBINAI Facebook / Instagram / X / YouTube