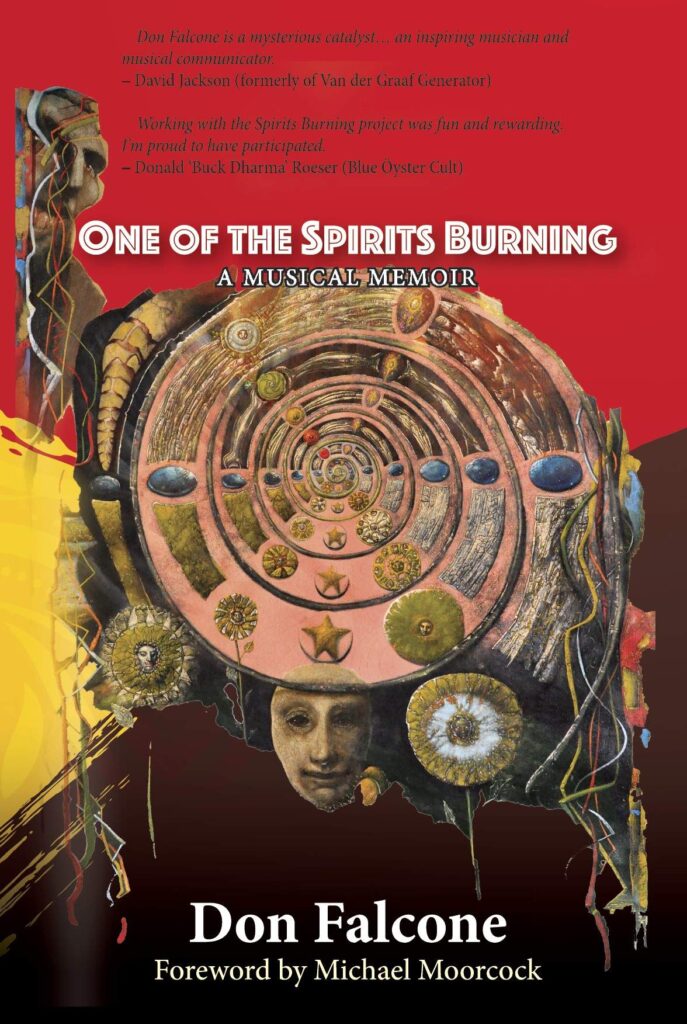

One of the Spirits Burning: A Musical Memoir with Don Falcone

Don Falcone’s One Of The Spirits Burning (A Musical Memoir), published by Stairway Press, charts the remarkable journey of Spirits Burning, from a local club band to a far-reaching, ever-evolving collective featuring nearly 300 musicians across 20 albums.

The memoir offers a candid, behind-the-scenes look at countless collaborations. Falcone—producer, multi-instrumentalist, and former tech writer—balances creativity with experimentation, openly reflecting on missteps and lessons learned. Contributions from more than 125 collaborators add depth, creating a layered portrait of Falcone and his projects.

Falcone’s work with legends like Michael Moorcock and projects such as Spaceship Eyes and the Daevid Allen Weird Quartet place Spirits Burning at the core of experimental music. His tech credentials, including writing documentation for Pro Tools and Dolby Atmos, provide a rare glimpse into the technical challenges and innovations that shape the music.

In the mid-90s, equipped with MIDI software and a borrowed Orban Audicy, Falcone produced ‘Kamarupa,’ reinventing Spirits Burning as a global studio collective. Musicians were invited from around the world to contribute, and the results were often surprising—like an ambient instrumental transformed by Italy’s Universal Totem Orchestra into something reminiscent of Magma.

Falcone’s laid-back leadership style, influenced by coaching softball and writing tech manuals, kept the sprawling collaboration on course. Even damaged cassette tapes and computer crashes couldn’t stop him—he once rescued guitar parts from a mangled recording. His openness to feedback, even criticism, is reflected throughout the memoir.

As producer, Falcone matched musicians to songs like a casting director, always sharing writing credits. Technical limitations often sparked creative breakthroughs; for one Moorcock album, he imagined “a thousand instruments” but found smarter ways to achieve the same fullness.

A rare live performance at Kozfest, captured on a live album, brought the collective’s studio magic to the stage. Earlier ventures like Spaceship Eyes and Melting Euphoria laid the groundwork for Spirits Burning’s distinctive sound, blending sampling, sequencing, and sonic experimentation.

At its heart, this memoir is a love letter to musical possibility. It explores how collaboration reshapes creativity, how technology and artistry intertwine, and how a collective spirit can fuel constant reinvention.

“I went into Spirits Burning already believing in a plural definition of space rock.”

Don, the book emphasizes the idea that “anything can happen.” Beyond the examples of recording with your heroes and collaborating with Michael Moorcock, could you share another unexpected turning point in your musical journey that truly embodied this philosophy?

Don Falcone: For my first fifteen years or so in rock bands, I was a musician and songwriter — first as a bassist who sometimes sang, and then as a keyboardist. I was lucky to always have a supportive engineer present, recording our demos, mixing live shows, or providing a voice at practices. In the mid-90s, while I was still a member of Silent Records projects like Thessalonians and Spice Barons, two things happened that changed my role with music forever.

First, someone got me a copy of Passport’s Master Tracks Pro, a MIDI software program of the time. Now I could record my performances of keyboard parts as MIDI data and mix them without the help of an engineer. Next, I was the lone technical writer at an audio company named Orban, and after AKG purchased Orban, I worked on the manuals for their digital audio workstation, the DSE 7000 (later renamed the Orban Audicy). I made a case to borrow one to better understand its capabilities. The powers that be agreed. Now I could record and mix audio at home. The combination of the MIDI tracks I had recorded and some new audio tracks became the first album I produced: my Spaceship Eyes solo project and the album Kamarupa.

And even more unexpected, I started to use the Audicy as an instrument — in the studio and onstage — sometimes to scrub or change the speed and pitch of spacey or industrial sounds, sometimes to act as a backing track for musicians to improv to.

You’ve collaborated with an incredible number of musicians in Spirits Burning. Can you recall a specific instance where a collaboration took a song or an album in a direction you never initially imagined, and what did you learn from that experience?

There was an instrumental piece I started for the Spirits Burning and Clearlight ‘Healthy Music’ album. A song I titled ‘Our Secret Cloud.’ It was built from my keyboard strings and what I called synth rumblies. It had an ambient flavor, almost like the soundtrack for a film. At my home studio, Cyrille Verdeaux did piano and organ parts that maintained the song’s airy sparseness. Pete Pavli provided haunting viola long distance. When I invited members of Italy’s Universal Totem Orchestra, I gave one instruction: Do not sing actual words. When I received the guitar and vocals they composed and performed for the piece, it almost made me cry. Suddenly, it was as if Magma was an ambient experimental band or if Ennio Morricone wrote modern ambient music.

Looking back, I think I re-learned what I already knew. Give people the opportunity, respect their judgment, and see what happens. It also goes back to a mantra I learned in my first bands: Surround yourself with musicians who care, who have passion, and who can do things that you can’t. It will make the result all the better.

‘Our Secret Cloud’ is on the CD included with the book (when ordered from Stairway Press of Jayde Design).

Your partnership with Michael Moorcock is a recurring theme. How did your understanding of his literary works evolve as you translated them into music, and were there any particular challenges in capturing the essence of his narratives sonically?

I’ve been immersed (or re-immersed) in Mike’s Dancers trilogy for over a decade, spearheading four Spirits Burning & Michael Moorcock albums. I always loved the trilogy and felt it was his best work. Rereading the books and working with the text has justified my faith and belief in their lasting power. What I (and Al Bouchard, my main collaborator for these albums) discovered was the depth of stories, phrases, and images within. We both wanted to make sure that we honored the original text and created something memorable and special.

Like the tentacles of the tale itself, there are multiple approaches that can be taken musically. How whimsical or clever do you make the music? How absurd? How magical? How theatrical? My first goal was to create good songs — well written — that told the story from song to song, with the flavor of the sound supporting its multiplicity.

I saw a challenge/consideration with the theatrical side. Do you mention characters’ names in songs (to tell a story, as Fairport Convention traditional songs like ‘Tam Lin’ and ‘Matty Groves’ do, and The Who’s ‘Tommy’)? Or do you exclude them so that the song has potential meaning outside the concept? For the Spirits Burning ‘Starhawk’ album (adapting a Mack Maloney book), I had done the latter for almost the entire album. ‘For the Dancers,’ Al had an influence, steering me toward being more theatrical for many songs, especially for the ones he transcribed from the books. Sometimes that worked well — the challenge met. There are probably some places, in retrospect, where we maybe could have excluded character names and made the song more generic. Maybe had more music to break up the lyrics too. It’s forever debatable — a challenge to decide which approaches to take when adapting a novel to music. I guess another consideration was whether to use first, second, or third person as the voice for the song. We ended up using all three, sometimes on the same song.

There was always room to experiment with sounds, and I or some of our contributors did that in places. In the same way the Dancers world is a menagerie of collected histories (although sometimes wrong, and comically misinterpreted — like ‘Carrie Joan’ instead of ‘Casey Jones,’ or that New York was once ruled by a king named Kong), I felt our Spirits Burning collective could always touch on different sounds and styles. While we didn’t really do any 19th-century musical styles (to cover the moments when the characters time-travel to Victorian England), I did attempt an old English accent on the ‘Thank You for the Fog’ piece.

The four albums do touch many styles: space rock, prog, psychedelic, art rock, folk, theatre, experimental, ambient, industrial, and a sprinkling of post-rock too.

We’ve just completed the fourth (‘The End of All Songs – Part 2’), and that will be coming out in the fall of 2025.

The transformation of Spirits Burning from a local club band to a sprawling collective is fascinating. What were some of the initial challenges in managing such a large and diverse group of musicians, and how did the internet facilitate this unique evolution?

What some reviewers in the early days didn’t understand was that the early albums were a mixture of local Bay Area musicians, musicians passing through (like Daevid Allen), and musicians who could record remotely (like Steven Wilson). Otherwise, yes, the internet was a big factor over time. I could invite more musicians that I connected with online, starting with those from the space rock communities in Europe and other parts of the U.S.

I didn’t feel any pressure managing many musicians or dealing with so many different sounds. Perhaps my time as a softball coach — working with a team — or being a tech writer and working on multiple projects concurrently helped. I would add a thank you to the late Gary Parra, too. He was the drummer for Cartoon, a RIO band that performed in San Francisco in the ’80s. I was friends with some of the band and had even played in an improv band with their keyboardist and wind/reed player. I connected with Gary in the ’90s when he placed an ad in a local weekly. We co-produced his first ‘Trap’ album, which had a dozen musicians. It was a blueprint for what I would later do with Spirits Burning, albeit with 30–40 people per album.

There were technological challenges: computer crashes — perhaps because I was pushing the system’s capabilities — track and sample rate limitations, digital cards unseating, and incoming parts that started at a different place in the timeline or went out of tempo deeper into the song.

There were some challenges with the musicians themselves. Sometimes it took a long time to get a part, and I learned to be patient. And, as I mention in the book, there were outliers, once-in-a-lifetime problems… like when Trev Thoms had his guitar performances eaten by his cassette deck. He sent me the cassette, with most of the tape wrapped around the shell and some of the tape ripped. I was able to carefully unwind the tape, fix the ripped portion, wind the tape back into the shell, and get one good playback to record his parts into my system. It kind of had a Mellotron warble in places, or a bit of acidic phasing. Both imperfections were kind of organic in their own way. In the end, I was happy to have him and his creative guitar work onboard and in place.

Including the perspectives of over 125 collaborators adds a rich dimension to the memoir. Were there any common threads or surprising revelations that emerged from these contributions, giving you a new perspective on the Spirits Burning legacy?

My invitation for their perspectives kind of mirrored my invitation for them to contribute musically. I was open to whatever they wanted to share — although I did ask them to keep it to just a few sentences, as I was concerned about word count.

There were many kind things said, and I appreciate that. It’s easy to take for granted and forget how many people you’ve touched positively. There were some very funny or odd statements, and that reminds me that at heart, music should be fun — and usually is.

The negative comments kind of stand out, given their low number, and did get my attention. For example, one person felt their vocals were mixed too low. While I didn’t think that was the case for the respective song, I know that I historically mixed vocals to a level just enough to be what I consider discernible — unlike pop music, which often has vocals that feel too far above the mix for my taste. I do respect the comment, and it’s a reminder for me to listen to vocal songs with renewed intent when finishing up a mix.

You mention that the book serves as a guide, even highlighting your own mistakes. Could you share an example of a significant mistake you made early on in your career and the crucial lesson you learned from it that you hope resonates with readers?

In an early chapter, I mention that I was center stage as a vocalist for the song ‘The Unknown’ at some San Francisco club gigs. My use of a prop and simple choreography went awry. Comically. Decades later at Kozfest (as covered in a subsequent chapter), I was once again center stage to sing ‘The Unknown.’ This time, I ditched the prop and had worked out a deeper, more mature choreography — one which I thought was more interesting, more special. And this performance did get a good response from the audience, live and in conversations afterward.

The main lesson is one of choices. I also cover this when I discuss choosing a band name or titling a song. There’s even a brief mention about the choices we make when buying an instrument. (I got a Sekova bass when the option to buy a Precision Jazz Bass was there. I made the wrong choice.)

In each of these cases, we learn about consequences. It’s okay to make a mistake. We’re human. What’s important is what we do with the experience. What do you learn? What do you do next time? How does the experience inform future decisions?

Hopefully, it’s clear in the book that I was able to move on from each of these — see the humor or craziness in what happened, even find the joy in retelling and sharing the story. And, where applicable, how I learned from it — and how the reader might, too.

As the composer, producer, and driving force behind Spirits Burning, how do you balance these different roles when working with so many individual creative voices, ensuring a cohesive vision while still allowing for artistic freedom?

Once I’ve started the song — or done my parts for a song someone else started — the keyboardist or bassist in me gets out of the way. With the producer hat now on, I think about song arrangement, mixing, and what is needed to create a good song that brings out the best in each sound, each musician. I kind of become a talent agent, looking for the musicians who can make the song sing. On one hand, it’s like a Mission Impossible motif, as I have hundreds of “agents” who have contributed previously. Plus, I am always trying to bring in new voices. Over the last few years, my research has resulted in bringing onboard singers like Erin Bennett and Roz Bruce. And sometimes persistence has paid off, where musicians like Bevis Frond’s Nick Saloman and former Hawkwind (now Hawklord) Mr. Dibs accepted a second or third invite.

There are mixing challenges, of course. Sometimes, a part sounds great in an early mix. Then additional parts arrive, and suddenly there’s competition in a frequency range, or even rhythmically. Sometimes a special moment seems to disappear. Sometimes an entire part feels buried. Over the years, I’ve gotten better at ensuring that early special moments are not lost, and that the music and vocals shine. I also find myself reviewing the moments where there are no vocals and seeing which instruments can be highlighted. Sometimes it’s the obvious solo. Sometimes it’s the underlying keys or a bass line. Or the entire band.

I think back to when I was a band member in a practice room, when everyone in the group was creating their own part. That’s what I want to recreate. That’s why I started to give everyone on the song writing credits — such that Spirits Burning is a band and not a solo artist.

If asked, or if I feel strongly about something, yes, of course I will speak up. And yes, there are songs where I have a definitive vision. For the song ‘Heavens Hide’ on an Spirits Burning & Bridget Wishart album, I remember asking guitarist Jerry Jeter to do something like Richie Havens over my keyboards and virtual drums, as I wanted to create a folkier landscape that would then support a spacier song with Bridget. With Jerry’s great acoustic guitar in place, that is how that song became a place for Nic Potter’s phased bass, Harvey Bainbridge’s spacey synths, Scotty Smith’s tasty percussion, and Bridget’s lyrics and vocals. Each of us shines in that piece. And we shine as one.

Your background as a technical writer for Pro Tools and Dolby Atmos is unique. Can you point to a specific instance where your technical expertise directly influenced your creative process in the studio or how you approached a particular musical challenge?

While not exactly technical expertise, knowing that the Orban Audicy had a documented number of splices (edits) available influenced a solo piece I did (‘An Isolated Craft’). I took a 1 kHz tone and then did the maximum number of allowable edits (10,000). Re-pitching, chopping up, copying and pasting slices of audio, adding effects, elongating, reversing audio, and so on — creating a 20-plus-minute ambient piece. True to the documentation, I could not do edit number 10,001.

A few years later, when I switched to Pro Tools, knowing limits was still important… for example, knowing the max number of voices (mono or stereo tracks) in a session might lead me to not invite one more instrument. Or, knowing that sax players like David Jackson and David Newhouse often give me multiple tracks, creating wonderful wind/reed ensembles, I now make sure to save 10 tracks for them. Just in case. Also relevant: the number of plug-ins. If I’m close to hitting the limit of plug-ins, I immediately consider recording an instrument track as an audio one.

When recently working on the last track of the SB/Moorcock ‘Part 2’ album, we were addressing the book and Mike’s vocal line of “a thousand instruments voicing a single note.” My plan: create 1,000 virtual instruments. I built a Pro Tools template with 100 virtual instrument (VI) tracks, thinking I could slowly and surely add in the plug-in sounds, and then bring together the results of 10 sessions — 1,000 sounds. Not so fast! It turned out that my older Pro Tools rig only supported 34 virtual instruments at once. Now, my laptop, which has a newer Pro Tools version, does support many, many more. So, I did the VI work on the laptop and then imported the stereo mix of each set of instruments into my main system. I stopped at 333. The mix of these instruments, along with existing audio tracks by Al and me, produced a full, dense sound. Any additional sounds were going to be hard to notice. There was no need to do 1,000 sounds just to say that I did 1,000 sounds. (One aside: I am in the process of getting a newer Pro Tools system.)

The “resurrection” of Spirits Burning in the mid-90s after its initial run in the 80s seems like a pivotal moment. What was the catalyst for bringing the project back to life in such a dramatically different form as a collective?

Spirits Burning had renewed resurrection pains in the mid-90s doing some tribute pieces — covers of King Crimson’s ‘Red’ and Genesis’ ‘Return of the Giant Hogweed.’ We didn’t really have a producer or a good handle on the recording and mixing tools on hand. The resultant songs were okay.

Next, the Spaceship Eyes ensemble that I had assembled for a few local shows got a gig opening for Belgium’s Present. And I decided to bring in some heavier numbers from the ’80s Spirits Burning catalog. We went with the project name “Spirits Burning vs. Spaceship Eyes.” Gary (Parra), who was the ensemble’s drummer, had moved from the Bay Area. I didn’t understand until later that he was the adult in the room — the glue that kept everyone professional and focused on dynamics. With Gary gone, and a new drummer in place, the electric instruments (guitar and bass) took over the sound. We would lose our tabla/bayan player and percussionist before the gig.

Once the gig was completed, I knew that I didn’t want a functioning band like this. Instead, I liked the flexibility of different line-ups — like Gary’s ‘Trap’ album, or Eno’s first albums. Soon, I started to invite musicians to celebrate space rock in a new studio-based Spirits Burning.

With so many musicians contributing to Spirits Burning over the years, were there any instances where a collaborator’s unique style or instrumentation fundamentally altered your perception of what space rock could be?

I went into Spirits Burning already believing in a plural definition of space rock. There was so much history there. The sounds of space rock bands, which covered different sound palettes, versus the not-necessarily-space-rock sound of bands with former Hawkwind members (think Moorcock’s ‘New Worlds Fair’ album, and many of the Calvert albums too). They were all space rock to me — or the context of space themes not necessarily wrapped in a space rock sound.

I remember when Knut Gerwers (who contributed to The Moors and then Spirits Burning) told me that he admired that I wasn’t trying to sound like Hawkwind, and that I was veering off into new space rock territory. Doing that, I was conscious that I was pushing the envelope and might not connect with all space rock fans. However, I knew that by including members of the global space rock community — musicians who, like me, were fans of Hawkwind’s history — we would sometimes touch their influence and move the needle too. Plus, there was a good chance that fans of their own space rock work would, at the least… check out Spirits Burning.

Many of the SB contributors, especially the early invites like Daevid Allen, seemed to embrace my idea of celebrating what space rock was and what it could become. Add to that, I felt their originality with SB songs pushed me to try new things. For example, with Daevid, that was with Spirits Burning and a couple of Weird projects: 2005’s Weird Biscuit Teatime and the Daevid Allen Weird Quartet. That 2005 release is getting a new physical CD pressing in 2025 as ‘Weird Biscuit Teatime Starring Daevid Allen’. It’s a remastered version and includes five bonus mixes too.

The account of the Live at Kozfest performance appears to be a significant part of the book. What was the most challenging aspect of bringing the often studio-based Spirits Burning to a live stage, and what was the most rewarding moment of that experience?

The book describes all the challenges — everything from deciding which songs to play, to assembling a live band, to me getting to the UK.

Most of the band challenges really came together in a positive, methodic way. Guitarist Steve Bemand was the UK manager of the band, making sure everyone learned the songs and showed up for practices. We then did an interesting tag team of Steve sending me the practices, me working out my parts in California, and then sending a new mix as if we were all in the same room.

I had fun with most of the travel aspects — partially because I never felt rushed. And I tried to pace myself through some of the ebb-and-flow issues that arose. The flight and airplane security concerned that my keyboard case housed a gun… getting my campervan, driving… In retrospect, driving with the steering wheel on the different side of the car, and driving on a different side of the road — that was the biggest challenge. It’s the one thing that I don’t necessarily want to do again.

Most rewarding aspect? We felt like a band. One composed of musicians I respected. I was proud of what we did while we were onstage (and how all our work up to that point had led to this successful rendition of Spirits Burning). Live photos and the after-show band photo captured the moments. As did the board mix. I was extremely proud that our performance was worthy of a live album — and that it was a space rock feast!

Having been involved in various solo projects like Spaceship Eyes and bands like Melting Euphoria, how did these diverse musical experiences shape your approach to the collaborative and ever-evolving nature of Spirits Burning?

Spaceship Eyes was my first (and really only) ongoing solo project. It was my sandbox — to build confidence in recording, mixing, and trying anything, especially when it came to using samples. The project got an unexpected boost when Cleopatra signed me and asked me to do drum ’n’ bass. From there, I was able to do an experimental take on the genre, and by the ‘Of Cosmic Repercussions’ album, combine aspects of drum ’n’ bass with space rock and prog. That combination continued with the early Spirits Burning albums. Some of the Spirits Burning bass energy and crazy rhythms reflect the Spaceship Eyes past.

Melting Euphoria was an interesting interlude in my music career. I was 33, and all the club bands I was in had extinguished. I was no longer under the illusion of “making it.” Instead, I just wanted to do interesting music, and the Melting Euphoria context was clearly a space rock one. It gave me the opportunity to recite some of my poetry, be a lead singer again, and essentially be the lead instrument as a keyboardist in a keys/bass/drum trio. The song ‘Disappearance of a Friend’ was really the first song where I thoroughly worked in voice samples, turntable moves, sequences triggered by a drum machine, and manual Audicy scrubs and varispeeds — all things that I would continue to do in Spaceship Eyes, and then Spirits Burning.

Looking back, we were fans of space rock. The band was our celebration of space rock. It’s that spirit that I would later resurrect with a more global crew and the Spirits Burning collective.

Headline photo: Three-fourths of Weird Biscuit Teatime — Daevid Allen, Don Falcone, and Michael Clare. Photo by Karen Anderson.

Don Falcone Website

Spirits Burning Website

Stairway Press Website

Order Info:

Americas (Book & CD): Stairway Press

UK & Worldwide (Book & CD): Jayde Design

Note: Online orders are book only. CD sold separately via order form in the book.