Judge Smith Returns with ‘Requiem Mass’ and ‘The Overstayer’

Best known as co-founder of Van der Graaf Generator, Judge Smith has spent the past five decades quietly subverting expectations.

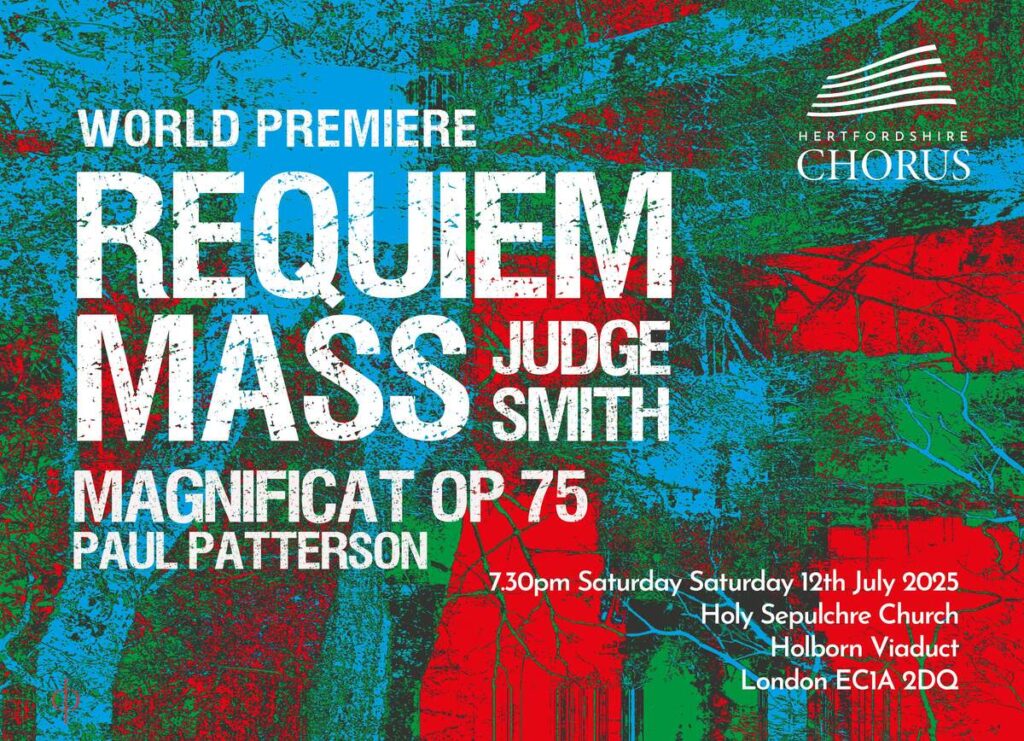

His latest projects—a long-awaited live premiere of ‘Requiem Mass’ and the new release ‘The Overstayer’—highlight his unique place at the margins of progressive music: literate, theatrical, and defiantly uncategorisable.

Originally conceived in 1973, ‘Requiem Mass’ combines rock instrumentation with the structure and gravitas of a Catholic liturgical mass. Smith, who doesn’t read music, composed the entire piece using sung dictation, jottings, and homemade chord tools. Now, thanks to long-time collaborator Ricardo Odriozola, the piece finally arrives fully scored and performed.

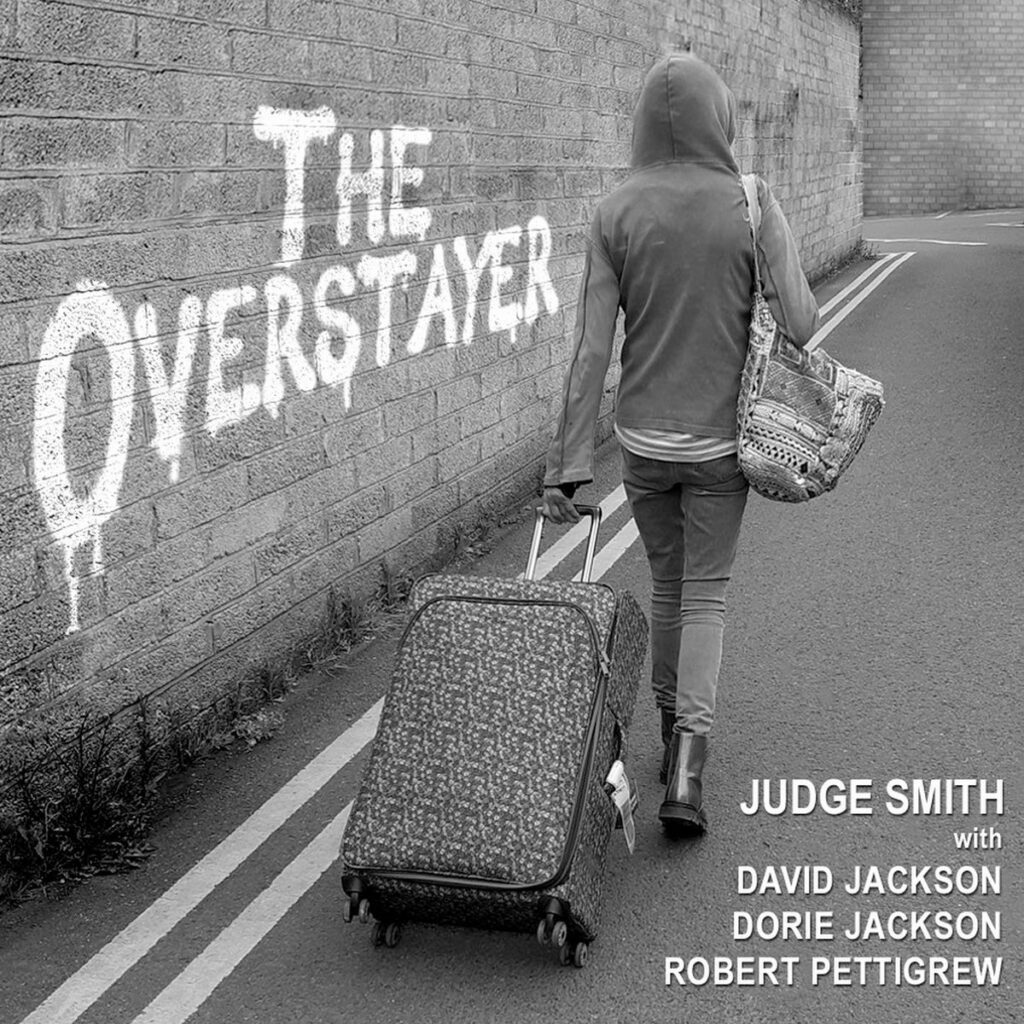

In contrast, ‘The Overstayer’ is a compact 18-minute narrative work following a fictional migrant’s experience. Scored for pipe organ and saxophone—an unusual yet compelling pairing—the piece features David Jackson (ex-VdGG) and his daughter Dorie on vocals. It’s a moving reflection on displacement, identity, and modern belonging.

Both works reflect Smith’s refusal to play by the rules. “Everything I’ve done is completely different to everything else I’ve done,” he says. That unpredictability is exactly what makes his work feel vital and timeless.

“I’ve always been able to imagine music and hear it in my head in great detail.”

So,’ Requiem Mass’ kicked off back in ’73. What was going on in your life at that time that led to this massive project? Was there a specific feeling or moment that sparked it?

Judge Smith: My band Heebalob had failed a couple of years earlier, and I had done an album of demos with the help of Peter Hammill, who was exploring the techniques of home recording. There was also the adventure of the Free Art Research Trio, the free music, improv, avant-garde noise band I had with Heebalob partner Maxwell Hutchinson (while working for him in his architects’ practice), which culminated in appearances at Ronnie Scott’s and the ICES 72 music festival at the Roundhouse. So I was just thrashing about for a new project.

How did you come to blend rock with the grand orchestral structure of the piece?

I was inculcated with the values of Prog Rock because of my time with the Van der Graaf Generator; we believed in the “long song,” grand musical themes, and weighty subject matter. I was also very fond of classical music of the dramatic sort—Stravinsky, Orff, Holst and so on—so I eventually hit on the idea of a ‘Rock Choral Requiem Mass.’ It’s so long ago now that I don’t remember what was going on in my little head at the time, but it was a pretty mad idea.

You’ve said you don’t read or write traditional music, so how did you actually pull off composing ‘Requiem Mass’ by dictation?

The answer is “with extreme difficulty.” I’ve always been able to imagine music and hear it in my head in great detail. So I would sing the tunes onto little Dictaphone tapes, write down lists of note names (I knew that much), and work out chord sequences using an autoharp and a modified guitar. I can’t play guitar, but I rigged this one with three strings tuned to a Major Triad and the other three strings tuned to a Minor Triad, so I could find every major and minor chord just by sliding my finger up and down. I wrote all this stuff down in jottings on paper, complete with squiggles to remind me of rhythms. I also did quite a bit of research into what the liturgical rules were for a ‘Requiem Mass.’ Not being a Catholic, this was new territory for me, but I wanted the piece to be “correct” rather than a made-up ritual.

I imagine it was a pretty unique experience, trying to communicate your ideas to Michael Brand. How did you go about it?

Michael was wonderful, but it was rather humiliating for me. For him, it must have been like trying to take musical dictation from a chimpanzee.

What was it like describing melodies and rhythms without having any written notes?

Well, I had my paperwork, such as it was, and my tapes, and my autoharp and comic guitar. I had also found the chords for one section on a little button accordion. Mostly it was me wailing and crooning at him. Amazingly, when he bashed it out on the piano, it was exactly as I imagined it. Michael did an amazing job.

In 2016, you worked with Ricardo Odriozola to revise the score. How was that different from when you first worked with Michael?

Well, firstly, I was a lot older, and I had picked up quite a bit more about music, although I still can’t play an instrument. I had sent Michael’s pencilled score to Ricardo in the post, and he had transcribed it onto a score-writing program, so there was actually something already there to start with. I had already worked with Ricardo on other pieces, so there was a good working relationship in place.

Was it hard for you to revisit it after all these years, or was it more of a natural process?

It was actually a bit spooky. There had never been a demo recording of Michael’s original transcription, so some bits I had actually forgotten about. There was also one “movement” that I had never been happy with, and had written a new piece back in the day as a substitute, but there had not been the need to get that down in music notation at the time, since I had had absolutely no luck trying to get it performed or recorded. So now we were able to get that new section written down, and the whole thing examined in detail, polished up, and improved in places. Ricardo is brilliant—an amazing musician—and for some reason, he’s keen on my music. So knowing him has enabled me to use other instrumentations, trained musicians, and sophisticated arrangements that I would otherwise never have been able to explore. I’ve had a lot of luck with my friends.

When you heard the new version, did it feel like the same piece you originally wrote, or did it sound different to you?

No, it sounded just as I remembered I wanted it to sound. It was definitely my piece, just the way I had imagined it.

Now that ‘Requiem Mass’ is finally being performed live, how does that feel for you?

I’m frankly amazed. I thought that, once the huge amount of work and (for me) the major expense of recording the ‘Requiem’ for the 2016 CD was over, that would be the end of it. I’m thrilled and delighted that it’s actually going to be heard live.

When you first wrote it, did you imagine it would ever be performed live, or was it just something that existed in your mind?

I imagine almost all my music being done live, even when there is little chance of it happening. ‘L-RAD’ (2008) would be pretty impossible, and maybe a live version of ‘Orfeas’ (2011) would be hard to imagine, but otherwise I always imagine it is being performed live, even when I am programming stuff on the computer, and I take a great deal of time and trouble to make it sound really real!

If you could change anything now, would you, or is it pretty much how you imagined it back then?

I wouldn’t change a thing. I love it. It’s not for me to say whether my music is any good or not, but I have to admit that I enjoy listening to my own stuff very much.

I’m really curious about ‘The Overstayer’ – what made you want to explore the story of a foreign teacher who overstays and becomes an illegal migrant?

Well, I’m interested in history, and that continual flow of peoples moving, over the centuries, from East to West. I’m also certainly sympathetic to someone living in a horrible country who wants to move to a nicer one. But I’m not coming to the story from a political standpoint. What do I know about it? I’ve given up having views of any sort about a lot of things. Views I’ve had in the past have so often turned out to have been completely wrong.

The instrumentation is interesting too – the pipe organ and saxophones. Why did you pick those specific sounds for this story?

David Jackson has recorded with Italian organist Marco Lo Muscio as Project One, and I was impressed with the sonorities of the two instruments together. Saxophonist Jan Garbarek has also recorded in a duet with pipe organ. So, though it is an unusual combination, it is not completely original. However, Jackson and organist Robert Pettigrew just sound great together.

Is this story based on anything personal, or is it more a way of exploring migration in general?

No, I have no personal connection with migration. My mother’s family seem to have been French or Belgian Huguenot in origin, but in the long run everyone’s ancestors were immigrants, even if it was some Neolithic folk wading across the Channel over the Dogger Bank.

You’ve got David Jackson back in the fold for The Overstayer, and his daughter Dorie is also involved. How did that come together?

Well, I have been collaborating with David for many, many years, and I wanted to write a new piece that would really feature him in his splendour. David has been playing for some time with prog band Kaprekar’s Constant, which featured his vocalist daughter Dorie. I became very impressed with her voice and with her sophisticated musical skills, so when thinking about making ‘The Overstayer,’ where the title character is female, it seemed obvious to invite her to take part.

How does it feel to work with David again? Is it like stepping back into familiar territory, or does it feel different now?

As far as David and I are concerned, it’s business as usual. I give him very precise instructions about what I want him to do, and he ignores these completely and does something much better.

What made Dorie the right person for the vocal role? How did you approach the collaboration with her?

She was right for the job because of a combination of the right voice, being a very nice person, who shares the same penetrating intelligence as her father, and the fact that the piece offered great opportunities for the massed multi-vocal harmony sections, at which she is so skilled. It was not an easy job. The Overstayer herself is from a (non-specific) foreign country. Should the singer try to use an accent? And how to sing the line “I can clean your toilets” completely convincingly?

Both ‘Requiem Mass’ and ‘The Overstayer’ are these big, ambitious pieces. Do you see them as part of the prog-rock tradition, or are you trying to do something different?

Well, ‘The Overstayer’ is only 18 minutes long, but I take your point. If we use the term “Prog” in its original, late ’60s sense—meaning “Progressive Rock Music”—then I would say yes, my stuff does fall into that category, even though quite a bit of my catalogue is not particularly “rocky.” However, I was never attracted to the acts that seemed to absolutely define “Prog”for so many years: Yes and Genesis and so on. I liked Zappa. Is that prog?

You’ve always mixed sacred or classical music with rock, and it’s a pretty distinctive part of your sound. When you do that, is it more about the contrast between the sacred and the secular, or are you trying to create a specific atmosphere?

I suppose that there are quite a few sounds or references to some types of “Classical” music, but then there’s also bits of jazz, bits of music hall, bits of punk, bits of “world music,” bits of heavy metal in there as well. And the only specific atmosphere I’m trying to create is one where people say, “Good grief! I’ve never heard anything quite like that before.”

“Everything I’ve done is completely different from everything else I’ve done.”

Looking back at your whole body of work, how do you see ‘Requiem Mass’ and ‘The Overstayer’ fitting in with everything else you’ve done?

One’s an early work and the other’s a late work, but I think they both fit in just fine. They both really sound like Judge-music to me, with lots of tunes you can remember and with a tendency to make you feel good at the end, rather than feeling bad.

How do you hope people will see these pieces in relation to your past work – as a new direction or a continuation of the themes you’ve explored before?

Everything I’ve done is completely different from everything else I’ve done. I like that about my stuff, but it has probably done nothing for my so-called career. A steady development of one particular style would have been a much better plan, but I would have got very bored. It’s the same with the visual arts. Painters never seem to find success until they “find their style” and start bashing out painting after painting that are very obviously by the same hand. Your work is allowed to change, but in predictable, logical steps. You don’t jump around all over the shop like I’ve done. But then I’ve never had anyone trying to ‘guide my career’: no manager, no agent, no publisher—and not for the want of looking. I never sold my soul because no one offered to buy it.

Klemen Breznikar

Judge Smith Official Website / Facebook / Bandcamp