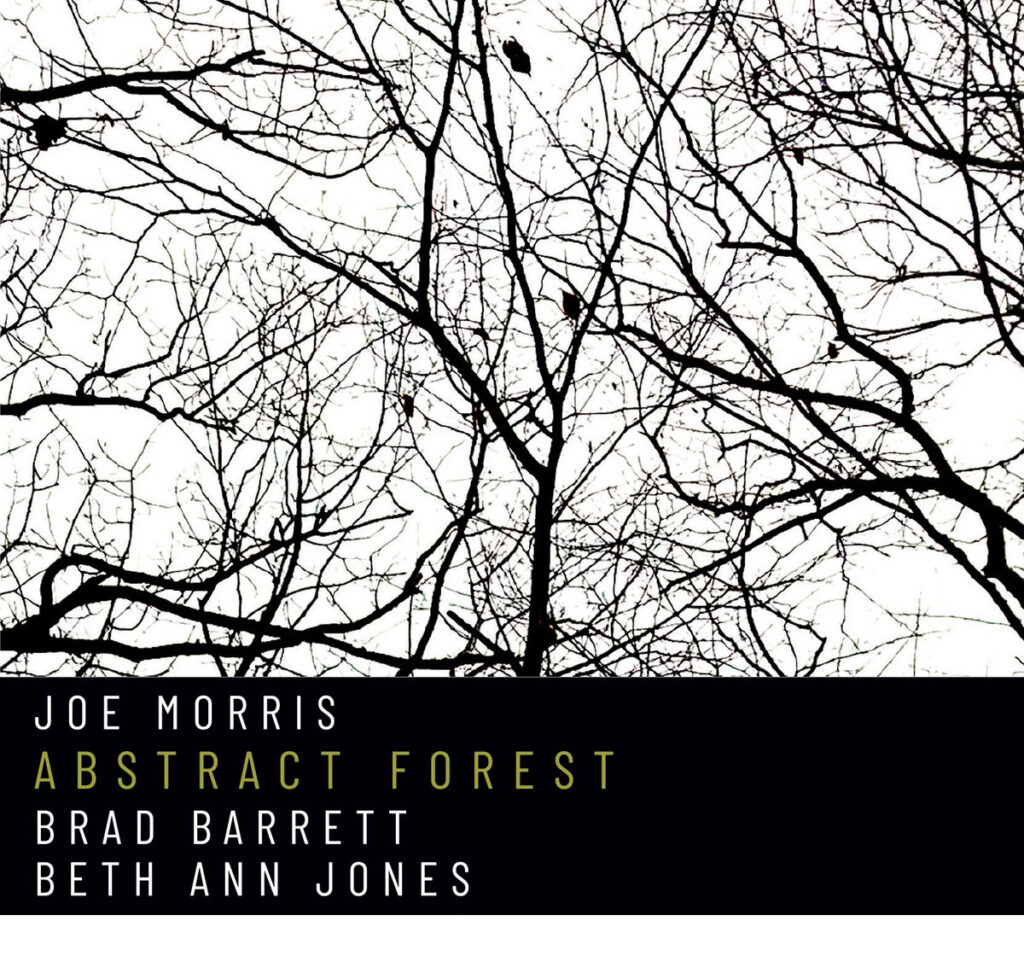

Joe Morris at 70: Instantiating the Continuous Beginning and ‘Abstract Forest’

A guitarist who plays bass. A free improviser who speaks in Instantiations. A musician who finds the most complex expression through the most efficient means. Joe Morris is a singular presence in creative music, a man of profound conviction whose art cannot be neatly classified.

He has spent decades building his own architecture of sound, one note and one methodology at a time. His approach is an act of deep personal construction, forging a unique voice through the rigorous study of global strings, saxophone inventions, and 20th century classical forms. Morris engineers sound, creating non linear systems where the abstract, the literal, and the emotional can coexist. He’s not content with academic aesthetics; the artist must take greater risks when the world is suffering, making music that offers an elevated experience.

This fuels ‘Abstract Forest,’ his new trio recording on Relative Pitch Records. Marking his 70th year, it’s a document of his main musical area, showcasing his proprietary methodology: a set of short schemes and interactive modes that generate formal structure spontaneously. Joined by Brad Barrett on cello and Beth Anne Jones on bass, the music is a masterclass in communal listening, where each player operates as an orchestra, helping to make it all work. Morris delivers a powerful, subversive message: persistence in one’s singular vision is an essential act, a continuous beginning.

“I’ve always worked to speak with my own voice in every part of this and to play my own music”

Your career spans decades, marked by a tireless exploration of improvisation and an idiosyncratic approach to your instruments. What enduring impulses continue to drive your creative process, especially as you approach your 70th birthday and this significant new release?

Joe Morris: I’ve always worked to speak with my own voice in every part of this and to play my own music. To do that, I have to do what I can to be like everyone I admire and create my own technique, my own way to play my instruments. Of course, no one has ever invented the entire thing. Everyone uses the technique they learn and then modifies it and adds what they want to it.

I want to make music that might offer listeners a chance to experience a moment of unique contemplation about something, anything. I also value the lesson in Black music about doing it in spite of the fact that it is outside of what is thought to be acceptable. To me, that persistence is a subversive act.

Considering that the world is burning and people are suffering, I feel that artists have to redouble the risks they take. It can’t be about academic aesthetics, success, or niche issues. We have to push it all farther and give people something elevated that offers new ideas. Music used to be very deep. It has to be deep again in a whole new way.

The recent Relative Pitch Records release is a special occasion, marking your 70th year. Could you elaborate on the genesis of this particular project and what makes it feel distinct or especially poignant in the context of your expansive discography? Furthermore, how does this recording reflect your current musical preoccupations?

The new recording ‘Abstract Forest’ is the latest document in the main area of my music. I call it Instantiation, which is a specific methodology that gives us control over things that are otherwise not clearly accessible. We can identify things that happen through listening and decide how to use them with multiple ways to interact. Working this way makes it possible to generate formal structure spontaneously using very short schemes. Everything is allowed. It gives us control over needing no control. ‘Abstract Forest’ features Brad Barrett on cello and Beth Anne Jones on bass. Both of them have an exceptional understanding of this methodology and the ability to use it.

Relative Pitch Records has a reputation for championing adventurous and uncompromising music. What was it about this label or its ethos that made it the ideal home for this particular 70th birthday release? Therefore, what kind of collaborative dynamic or artistic freedom did you find in working with them?

Kevin Reilly, who owns the label, deserves all the credit for that. He is a unique listener, supporter, presenter, and producer of music that he likes. He would never ask for it, but he deserves recognition as a very important person in this period of improvised music. He’s one of the best people to ever do what he does.

He’s been very supportive and accepting of my music. I have complete freedom to do whatever I want.

Throughout your career, you have consistently pushed the boundaries of guitar and bass playing, often employing unconventional techniques and embracing sonic textures far removed from traditional jazz or rock. Could you discuss the evolution of your unique instrumental language, considering the influences that shaped it and the deliberate choices you made to forge your own path?

When I was about 18, I focused on listening to saxophonists, violinists, pianists, more than guitarists, although I made a serious study of the guitar before that period. I was interested in invention, the players who created the way they played and influenced all of those who interpreted them. I listened to a lot of African string music and 20th-century classical music. My playing is made up of bits I took from all of these sources, altered by my own sensibilities.

In 2000, I bought an upright bass on eBay and started playing it. I used the same process I employed on guitar on bass. Although my desire to play bass was a bit less focused on originality than it was on guitar, I still wanted to make my own decisions about how to play it. I can say that working this way causes a lot of people to disregard my playing on both instruments, which is fine with me, because I know exactly what I’m doing. I can cite the source and theoretical formula of everything I play. And no matter what sounds or phrases I play, I can sing all of it, so I know it’s music.

It dawned on me about 10 years ago that while I am either appreciated or not as a jazz musician, or as an improvising musician, I am actually a psychedelic musician who uses improvisation because it is the most efficient way to play complex music. My objective is to take listeners someplace. This is my way of doing that.

Your discography reveals a consistent engagement with various ensemble configurations, from solo performances to duos, trios, and larger groups. How does the specific instrumentation or the nature of your collaborators influence your approach to improvisation and composition? At the same time, what are the particular joys and challenges presented by different musical settings?

Dialogue is important to me. Smaller groupings make that easier unless everyone in a larger group knows how to operate that way. While I am able to arrange larger groups that can play that way because my community is large and full of very capable players, the issue of money, or the lack of enough of it, prevents me from working with bigger groups. That said, I like working on a small scale. If I had the money, I would just do more and pay people more. No opera or symphonies for me. My solo music is quite complete for me. One or a few more people is also great and enough.

“Improvising is about stating, accepting, and adding to what is happening.”

Free improvisation is often at the heart of your work. How do you define “freedom” within a musical context, and what responsibilities do you feel an improviser holds to the present moment and to the collective sound? Furthermore, how do you navigate the delicate balance between individual expression and communal listening in improvised music?

I interpret “freedom” as using a methodology that sets the parameters that the musicians work in. Everything I have ever done has employed a methodology that is either started, discussed, or assumed by the people using it. My goal all along has been to create my own operational methodology that was different from those that are what I call the seminal methodologies that define “free.” They are free of the rules of harmony but otherwise very specific in the way certain musical properties are modified by either the composers or the collective who created them. I think I have a very solid repertoire regarding so-called “free” music. By that, I mean I can improvise with anyone because I can hear the methodology they are using. I define “Free Music” as music done free of the oversight of institutions, the critical establishment, and the music business. Following that definition frees me to do whatever I want.

Improvising is about stating, accepting, and adding to what is happening. In acting, they call it Yes-And. Helping to make it all work. A very developed and refined ability to listen, and the capacity to identify specific things in the layers of sound in an immediate way, combined with a highly capable facility on one’s instrument, an open mind, and a helpful attitude are all necessary.

As to the last part of the question: it was established that in Free Music, each player is an orchestra. I work two ways. One is playing with people and either assuming that they will follow a kind of way of playing that is typical for them or their community and the one or more methodologies in play, and working in that way with them. The other way I work, in my Instantiation music, we use five modes of interaction, which enable us to do whatever we want and always have choices and ways to change and expand just by using a different interactive mode.

You have been a significant figure in the avant-garde music scene for many years, witnessing its evolution and facing its challenges. What shifts have you observed in the reception and understanding of experimental music over the decades? Therefore, what advice would you offer to younger musicians striving to create uncompromising art in today’s world?

I think it’s the same as it’s always been, although some of the essence and the aesthetic language of it has been kind of appropriated and used to describe something that is much more about other things. The parts that matter to me and the reasons I do it are quite constant. It’s a hard slog. We do it because we have to. I work hard, and a lot of it is DIY, and I am grateful for that.

I think the use of the term “Experimental Music” is a mistake. It implies that it isn’t music until someone says it is. I think music is music whether people understand it or not. But as a “Free Music” musician, I reject the idea that oversight matters to me.

I tell my students that it is hard to do. I never tell them what to play or what is good or bad in music. But I do tell them if they take the high road and try for innovation, to play what they really believe in, because that will help them to endure the difficulties and proceed on their terms. I tell them to never, ever let it wreck their lives. Do the work it takes to be happy and healthy. Have loved ones around them, experience the world, nature, etc. Grow old and play music for as long as they can. I offer the idea that they might see their lives in music as an interesting adventure.

Your music, while often abstract, possesses a profound emotional resonance for many listeners. How do you reconcile the intellectual rigor of your improvisational practice with the visceral, emotive qualities that emerge in your performances?

The rigor is necessary to create a workable platform for what I hope to express. Constructing a unique operational methodology takes a lot of thought, time, and effort. It takes new ideas and new language to build it.

An old friend and a huge influence on my thinking is Margaret Hamilton, who wrote the onboard computer software for the first Apollo moon landing and coined the term software engineer. She helped me to think differently and to organize my ideas differently. Because of her, I think of it as engineering sound instead of an intellectual theory. Built into my methodology is the logic that everything can be made to function in multiple ways, so I don’t have to leave out anything, and I don’t have to be strict about how any sound and other musical objects interact with each other. I am a non-linear thinker, and my music is built in a non-linear system that can be abstract, literal, and/or emotional.

Teaching has also been a part of your journey, sharing your insights with aspiring musicians. What are the most crucial lessons you aim to impart to your students, particularly regarding improvisation, creativity, and the pursuit of a unique artistic voice? Moreover, how has teaching informed or enriched your own musical practice?

All of my students have a voice and some kind of desire to use it when I first meet them. So I try to hear that and then do what I can to help them develop it. The assumption is that originality happens like a lightning bolt. Maybe, but students are there to learn. My approach is additive, giving them new useful skills and information. I don’t subtract what they know, and I don’t critique what they play.

We use scores that are the compositional component of the methodologies we study. We use recordings of the music that don’t employ scores. They learn to work in these methodologies so they can play with people who use them, and so they don’t make the mistake of thinking that playing like that is their own invention. This opens them to consider what isn’t there, which might become something of their own invention, and to utilize two or more things as composites. The results are often amazing.

Beyond that, I always encourage them to play whatever they want and to take creative risks as far as they want, but to never, ever let any of it wreck their lives. My hope for them is that they will do the work it takes to be healthy, happy, functioning people who are able to deal with the responsibilities that come with living life as an artist.

The concept of “silence” or “space” often plays a crucial role in improvised music. How do you perceive the function of silence within your own playing and within the tapestry of your ensembles? At the same time, how do you utilize moments of quietude to shape the narrative or tension of a piece?

I think of it as the degree of density. But my music is dynamic and not static. By that, I mean I never try to make one repetitive thing or intentionally use silence or space as a formal device. But I do use a proportional expression of the pulse and a concern for the envelope of the sounds I make. Those techniques and rests of every duration allow a lot of silence that can express degrees of emotion or not express it at all.

Beyond the purely musical, what philosophical or artistic principles underpin your approach to life and creativity? Do you see a direct correlation between your personal worldview and the music you create? Furthermore, how do these deeper convictions manifest in your improvisational choices?

I have a casual interest in phenomenology. It helps to support my belief that I can know a lot about something that is actually beyond mine or anyone’s full understanding. This really supports the creative decisions I make, including immediately in a performance. And it helps me to let the music be as it is and let listeners draw their own perceptions and ideas of what the music means to them.

The journey of an artist is often fraught with both triumphs and periods of self-doubt or creative struggle. Could you share an experience where you faced a significant musical challenge and how you navigated it, ultimately leading to growth or a new understanding?

In 2000, after years of developing a voice on guitar and as a composer and having some good success with my groups in performance and recordings, I broke up my quartet and changed everything.

During the previous 25 years, I also did other music. All of it was part of a very multi-faceted, varied approach that I charted out for myself around 1980.

As I tried to get my solo music and other different ensemble music heard and working like my trio and quartet had, I met real resistance from label owners, promoters, and critics, many of whom told me that the stuff they knew about was “my music.” I asked them where they were when I started those parts of my music, which I decided had run their course, and that it was time to do other things that were also “my music.”

Anyway, I walked away from that part of my music and the people who said those things and went to work on the other parts. This is when I bought a bass, recorded solo music, and more completely improvised music in small groups without drums, playing with a lot of new people from different communities of musicians. It’s also when I was invited to teach at New England Conservatory.

It was a difficult time, but it was also a new beginning. Since then, I’ve come to understand that everything has been a beginning. Now I say that my experience in music is a continuous beginning. Sometimes I wish I could get more support so that I can just roll on and not try so hard. But mostly, I am grateful that it’s the way it is.

Looking back at your extensive body of work, are there particular recordings or collaborations that stand out to you as very important moments or as encapsulating a specific artistic phase?

They are all important to me. I’m confident that I have never repeated myself. I’ve made recordings that matter to me with very important well-known musicians and people who are less known, and also many who are unknown. There is always something in all of them that has managed to make them unique. That said, I have recorded with as diverse a group of improvising musicians as anyone could ever imagine and performed with an even bigger and more diverse one. It all matters to me.

You began playing guitar in 1969, a truly transformative period for music, and notably shifted from blues to a deep engagement with jazz and new music after hearing John Coltrane’s ‘OM’. Could you describe the initial spark that ignited your passion for improvisation and experimental sounds during those formative years? Furthermore, what was the broader musical climate like in New Haven at that time, and how did it either nurture or challenge your burgeoning interests?

As I mentioned above about being a psychedelic musician, the void after Hendrix left was filled for me by the impact of hearing ‘OM’ and what followed that. It and the rest took me to a new place and pointed me in a direction that made sense to me, one that I thought I could work in for the rest of my life. One that supported the values I held about life, justice, and decency.

Coincidentally, New Haven was a small but vital place for this approach in that period. I attended a student-run high school with an open curriculum. I spent every day playing and listening to music. The school was one block away from the Yale University School of Music. I attended free recitals all the time, hearing Stockhausen, Messiaen, Stravinsky, and much more. I saw Miles, Rashid Ali, Andrew Cyrille, and many other jazz greats there. New Haven has regular train service to New York, so I could go there to hear music. Anthony Davis, George Lewis, Mark Helias (who were Yale students), and Gerry Hemingway (who wasn’t) played in New Haven a lot. Wadada Leo Smith lived in New Haven and performed a number of times. Two local radio stations played every kind of music from gamelan to free improvisation. I had friends to play with too. New Haven was like an open-air conservatory for me.

Your move to Boston in 1975 and subsequent involvement with the Boston creative music scene, including the formation of the Boston Improvisers Group (BIG), marked a significant chapter in your early career. What was the energy of that specific avant-garde community like, and who were some of the key figures or collaborative experiences that profoundly shaped your understanding and practice of improvised music during those years? How did that environment differ from other musical hubs of the era, such as New York, in terms of its unique character and opportunities for emerging experimental artists?

There was a lot going on in Boston then and quite a few places to play. Having been in New Haven prior to that, it was clear that I had a different view of the wider scene than the people I met in Boston. Most of what happened there then was like Coltrane, and fusion, but there was a bit of activity that was more interesting.

Still, there were venues and clubs that brought in people I was very interested in. I saw the Revolutionary Ensemble, Anthony Braxton, Ornette, Julius Hemphill, and others not long after I arrived. And I found local musicians to play with. All of that grew over the first five years I lived there.

In 1980, I met Lowell Davidson, who, in the eight years we worked together, became a huge influence on me. I met a great drummer named Tim Roberts, who I played duos with for a couple of years, and Sebastian Steinberg, who played bass with me for about eight years. Although I was never a student, I met a lot of good players from New England Conservatory. Frank London, the trumpeter, and I started the Boston Improvisers Group (BIG) as an umbrella organization to support the many separate performances that were happening in town in the early 80s.

Boston wasn’t good at supporting our music. Frankly, it still isn’t for the many great musicians who live there now. It certainly didn’t compare to New York, but it was a very livable city. I always focused on New York and got some opportunities to invite some New Yorkers to Boston to play. So I had Joe McPhee, Andrew Cyrille, William Parker, Billy Bang, Peter Kowald there to play with me in the early 80s, and I also booked a festival and a couple of clubs. I moved to New York in 1985, and I was glad to leave. I returned for personal reasons in 1989 and stayed until 2001 when I moved to my current home in New Haven.

Before establishing your own Riti label in 1981 and releasing your debut Wraparound, you dedicated years to developing your distinctive approach to the guitar, often in self-taught fashion. Could you recount some of the moments or breakthroughs in your personal exploration of the instrument during your very early playing days, particularly before your initial recordings?

I owe a lot to alto saxophonist Jimmy Lyons, violinist Leroy Jenkins, and kora master Alhaji Bai Konte for the incredible inspiration I found in their music. It all had a serious impact on my guitar playing. And to Lowell Davidson, who might be the most unique and brilliant musician I’ve ever met.

In 1981, I just went to Europe and stayed there for three months. No gigs. Just a rail pass and my acoustic guitar. I landed in Brussels. On my way to the hotel, I saw a man putting up a poster for a concert by James Blood Ulmer. When I stopped to read it, he asked me if I played music like that. I said yes, and he asked me to bring him a tape at the club that night. He hired me to open for Blood. I was in Europe for an hour and had a good gig. A similar thing happened the next week in Amsterdam at the Bimhuis, where I opened for Abdullah Ibrahim.

Seeing the local organization in Europe, I went back to Boston with a renewed focus and really got busy. I organized my trio and made the live recording that became Wraparound, which got me some good attention and helped to change my situation.

What are some of the most important players that influenced your own style and what in particular did they employ in their playing that you liked?

In addition to the ones I mentioned above, I have to add Anthony Braxton, Eric Dolphy, Evan Parker, Barry Guy, Fred Hopkins, Malachi Favors, and William Parker. I appreciate Rev Gary Davis, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Django Reinhardt, Rene Thomas, Hendrix, Pete Cosey, and Derek Bailey equally. All of them are combined in my music with everyone else. Finally, Albert Ayler might be the biggest inspiration for me. I teach his music using his compositions to my students. From that, I am reminded that he might still be the most misunderstood musician of the 20th century. His compositions are amazing. His expression is supreme.

As you embark on this new chapter marked by your 70th birthday and this special release, what artistic horizons still beckon to you? Are there unexplored musical territories or new collaborative ventures you envision for the future?

I have always composed, but I don’t always know what to do with the pieces I write. Recently, I decided to use them in groups I assemble in which I play bass. This enables me to have melodic composed music, different from the Instantiation scores I make, and use it as a platform to play bass in ways that are different from other things I’ve done. The first release of that music is a double CD live recording with Anna Webber, Rob Brown, and Matt Rousseau that will be released on the Fundacja Sluchaj label in 2026.

Otherwise, my focus is on Instantiation and finding ways to perform with the large group of my former students who are spread out around the world and who understand that methodology.

Klemen Breznikar

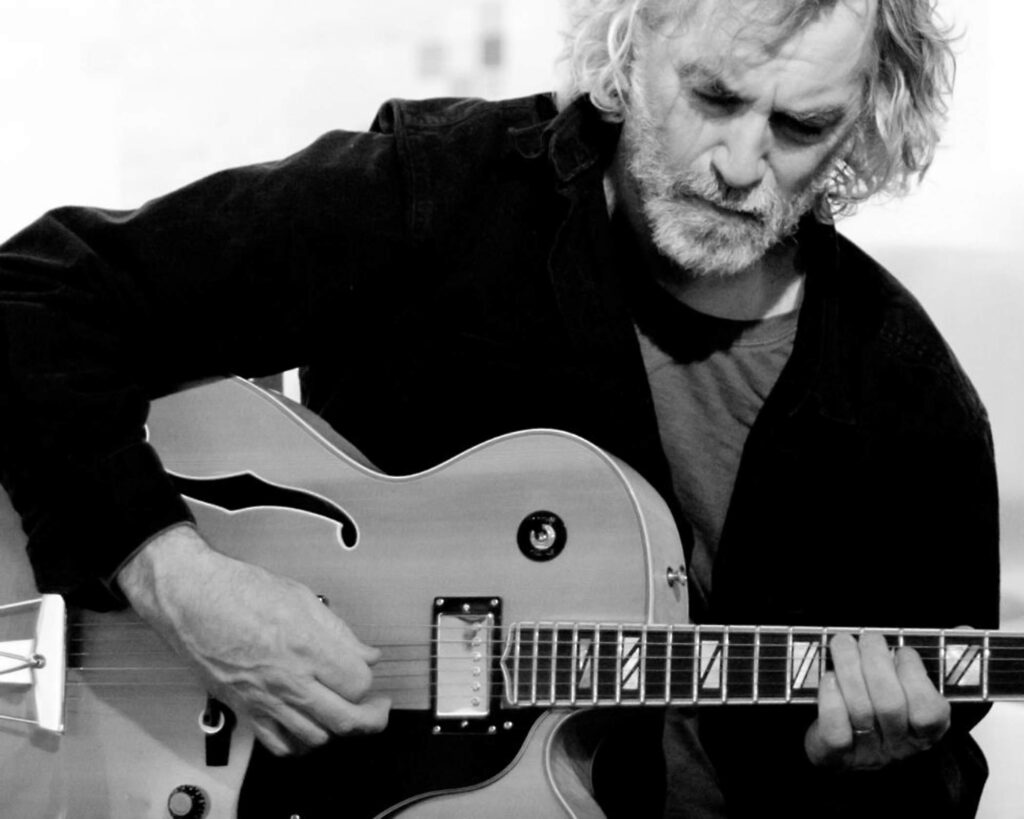

Headline photo: Joe Morris (Credit: Peter Gannushkin)

Joe Morris Facebook / Instagram

Relative Pitch Records Instagram / Bandcamp