Digging Into the Sound of Trizo 50 & Phantasia: An Interview with Private Press Legends

Private press records have a special charm for collectors because they offer honest snapshots from times when mainstream routes were not an option. Bands like Phantasia and their later form, Trizo 50, perfectly capture that passionate, underground creative spirit of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Phantasia, born from the creative urgency of John DePugh, David Johnson (DJ), and Bob Walkenhorst (BW) in rural Norborne, Missouri, initially operated as a local dance band, adept at covering the hits of the era. Their 1969 private press album, however, unveiled a more introspective and “trippy” dimension, showcasing a band grappling with original material often rooted in John DePugh’s poetic leanings. This debut, pressed in a mere 25 copies, has since become a highly sought-after rarity, valued at well over $4,000 per copy. It represented a conscious decision to capture their unique sound on tape, driven by John DePugh’s initiative. Recorded in a single day at Damen Recording Studios in Kansas City, MO, with George Damen producing, the sessions captured DJ’s songs live and Walkenhorst’s with more overdubs. The album’s lyrical depth, influenced by King Crimson’s Peter Sinfield and Edgar Allan Poe, set it apart.

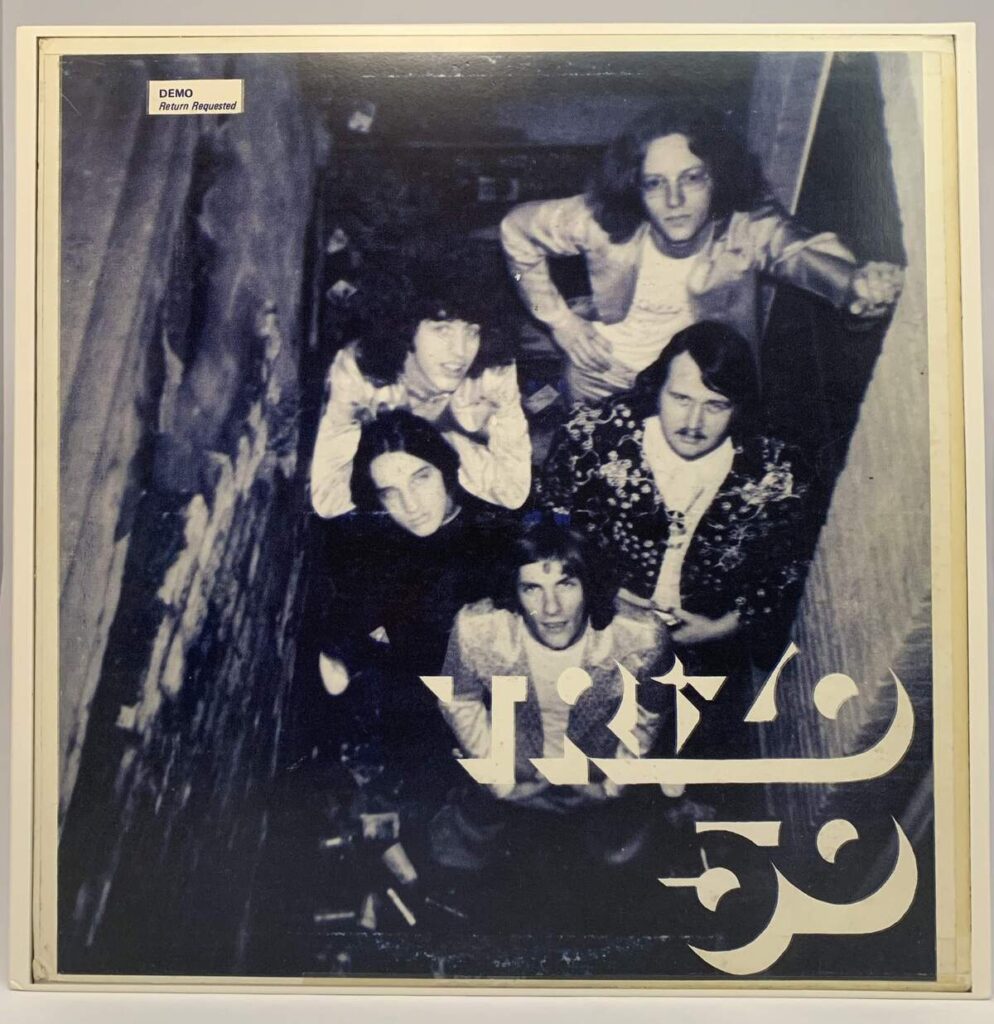

The transition to Trizo 50 marked a significant shift in identity and musical direction. By early 1973, with a revitalized lineup including Bob DePugh on keyboards, the band sought to consciously move towards “rock songs that could get on the radio,” distancing themselves from Phantasia’s earlier sound. The name “Trizo 50” itself, derived from a veterinary pharmaceutical product, symbolized this new, more contemporary aesthetic, influencing their stage presence with sateen outfits. The Trizo 50 album, also a private press, saw 100 copies produced after an exhaustive recording process. Recorded entirely on a TEAC 2340 4-track reel-to-reel, the band embraced a DIY approach, albeit with inherent limitations in fidelity due to repeated track mixing. This period, fraught with personal and familial tensions, nevertheless yielded a diverse collection of tracks chosen democratically by the band members.

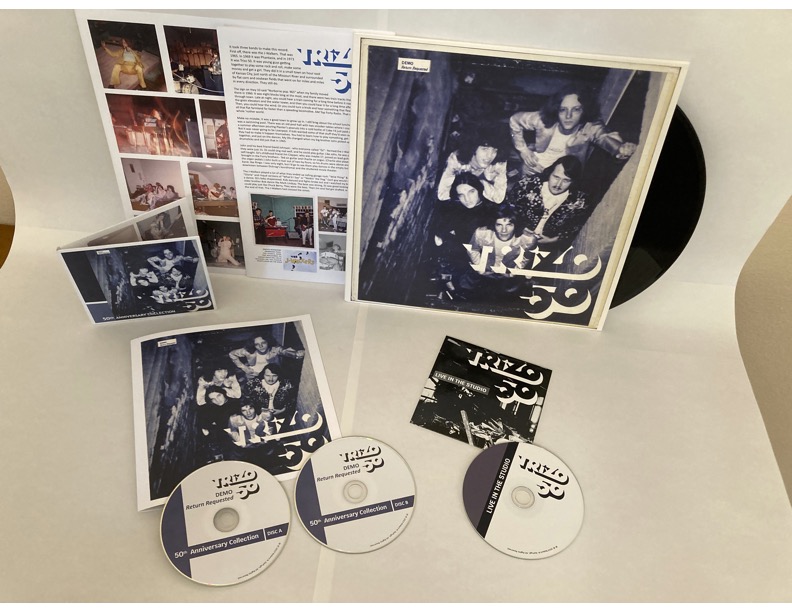

The legacy of both Phantasia and Trizo 50 has been thoughtfully preserved and brought to a wider audience through various reissues over the decades. John DePugh initiated LP compilations like ‘A Psychedelic’ and ‘I Talk to the Moon’ in the early 1990s through the Ton Um Ton label in Austria, which were well-received in the European psych community. Later, John licensed the Phantasia and ‘Walkenhorst–DePugh’ albums to World In Sound of Germany, which significantly contributed to putting Phantasia “on the map”. The recent comprehensive reissue of Trizo 50, personally remixed by Bob DePugh from the original 4-track tapes, serves as a definitive snapshot of the band’s talent, offering a complete narrative and superior sound quality that finally allows the nuanced contributions of all members to be fully appreciated. These releases solidify the importance of Phantasia and Trizo 50 not just as obscure private press entries, but as significant, albeit previously undersung, chapters in the history of American independent rock.

“We pressed 100 copies, with a crack-and-peel front cover.”

Let’s start at the beginning. What was life like growing up in your town? What was your world like back then as kids? What did your folks do?

Bob DePugh: I had a pretty great childhood. I grew up in Norborne, Missouri, a farm town of just over 900 people an hour east of Kansas City. My family moved there from the city in 1960 when I was four years old. I was the youngest of five kids at the time. The town was already in decline, with several closed storefronts in the small four-block “downtown”. The movie theatre was closed, the marquee removed. The only traffic light was at the edge of town, where the state highway skirted past. The town began as a railroad stop in 1868, but the trains hadn’t stopped at the boarded-up train station for years. Except for a new elementary school and a few others, the buildings were all from the turn of the century. Many of the older houses had ornate wooden fences and porch railings, and we were surrounded by corn or soybean fields for miles.

There were four full seasons: green springs with massive thunderstorms that sent water rushing down the streets, summers that were three months of sullen sweat and cicadas, fall colors of yellow and red and gold against popsicle blue skies, and white winter snowdrifts taller than my head over the entire town. There was a swimming pool and a Dairy Spot and a pool hall and a small library. We had an annual soybean festival in the summer, and a carnival came to town every fall. It was really more like the ’40s than the ’60s, and it was kind of magical for a young boy.

The old man had a veterinary pharmaceutical business in one of the newer buildings. My mom and all the kids worked in the factory there after school, nights, and weekends, making, bottling, and shipping various powders, pills, and ointments. I didn’t mind so much; I liked being around my older brothers and sisters. It wasn’t so great for them, because they remembered living in the city and going to bigger schools. Norborne was a big step down for them. They all had to adjust, and they did. When not working, their lives were typical American high school — proms, plays, football games, and homecoming queens. I was into comic books and monster model kits and James Bond.

How did music first enter your lives? Do you remember the first records or singles you got your hands on? Was there a moment when something just clicked?

There was always music. The older kids felt like they were stuck in the boondocks, so radio was about the only thing that kept them in touch with the modern world. I remember them singing songs like ‘Tom Dooley’ or ‘If I Had A Hammer’. Back then, small radios were pretty common, so whenever the old man was out of town, we’d play the radio while we worked. WHB-AM in Kansas City was our station, but at 8 p.m. they powered down and we could pick up WLS from Chicago.

My eldest brother was ten years older than me, so the first albums I remember in the house were his: ‘Elvis Golden Hits II’, ‘Ray Charles Greatest Hits’ and ‘Live in Newport’, Dave Brubeck’s ‘Time Out’ and ‘Time Further Out’. Then my brother John, who was seven years older than me, got into the Beatles. It felt like ‘Meet the Beatles’, ‘The Beatles’ Second Album’ and ‘Introducing the Beatles’ all appeared at once. We’d watch Ed Sullivan whenever we could, and I just loved the Supremes.

The first 45 rpm I remember seeing was ‘Only Love Can Break A Heart’ by Gene Pitney, but John also bought a lot of the Beatles singles, and ‘Roses Are Red (My Love)’ by the You Know Who Group. Also ‘My Pledge of Love’ by the Joe Jeffrey Group and ‘Hello Stranger’ by Barbara Lewis. We got more Beatles albums, and Stones, and the Zombies album with ‘She’s Not There’ / ‘Tell Her No’ and ‘Summertime’ on it. And pretty much all the Dylan albums. John was big on buying greatest hits albums, which we had by the Hollies, the Lovin’ Spoonful, the Animals, the Young Rascals, the Byrds, the Turtles.

The first two records I bought myself were TV offers: ‘The Incredible World of James Bond’ — a collection of tracks from the first three movies — and a Batman record released by a bubble gum company by ‘The Fantastic Guitars of Dan and Dale’. I learned years later the band were all from Sun Ra’s orchestra. Then in 1967, on vacation in Colorado to see our grandparents, I bought ‘Sgt. Pepper’ and the soundtrack to ‘Casino Royale’.

Were there any local bands or clubs in the late ’60s and early ’70s that got you fired up or gave you a sense of what was possible?

We were always the only band in town, and there were never any clubs in or near Norborne. There were bands from other towns: The Panics, The Alley Sweepers, The Wild Things. Everyone played at high school dances or in local VFW (Veterans of Foreign Wars) Halls. By the early ’70s, there weren’t so many, and there was never anything about the local scene that indicated any possibilities beyond having some fun. Anything beyond that was pure imagination.

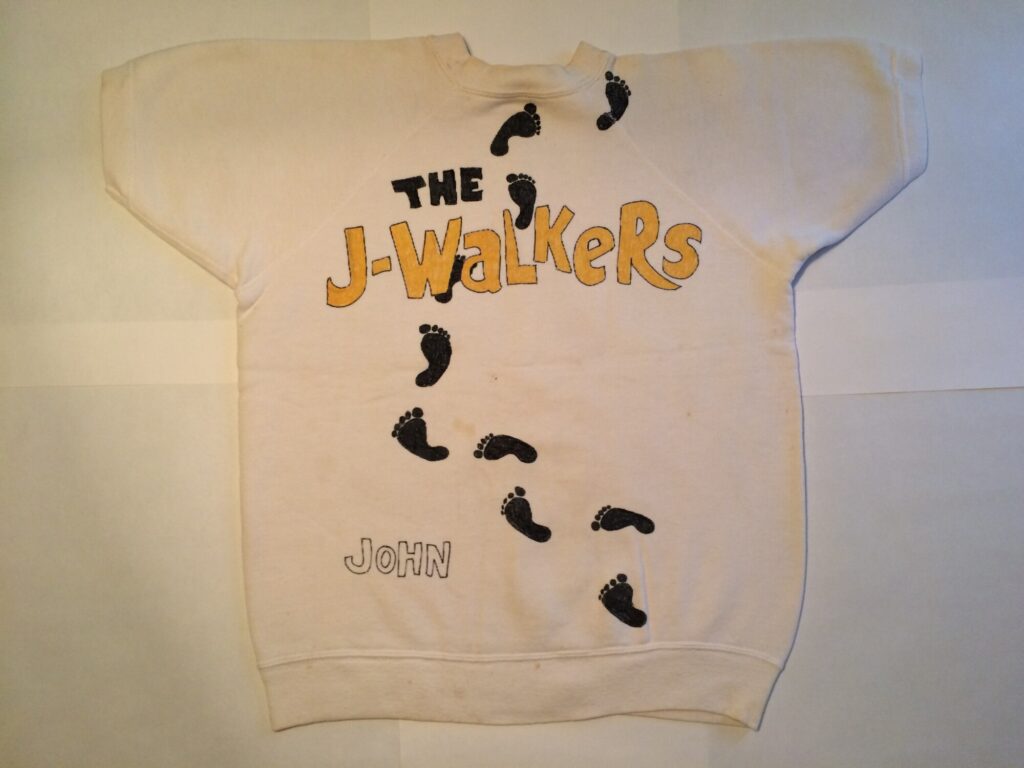

Tell us about the J-Walkers — how’d you all come together? What kind of songs were you playing back then? Ever do any battles of the bands or school dances?

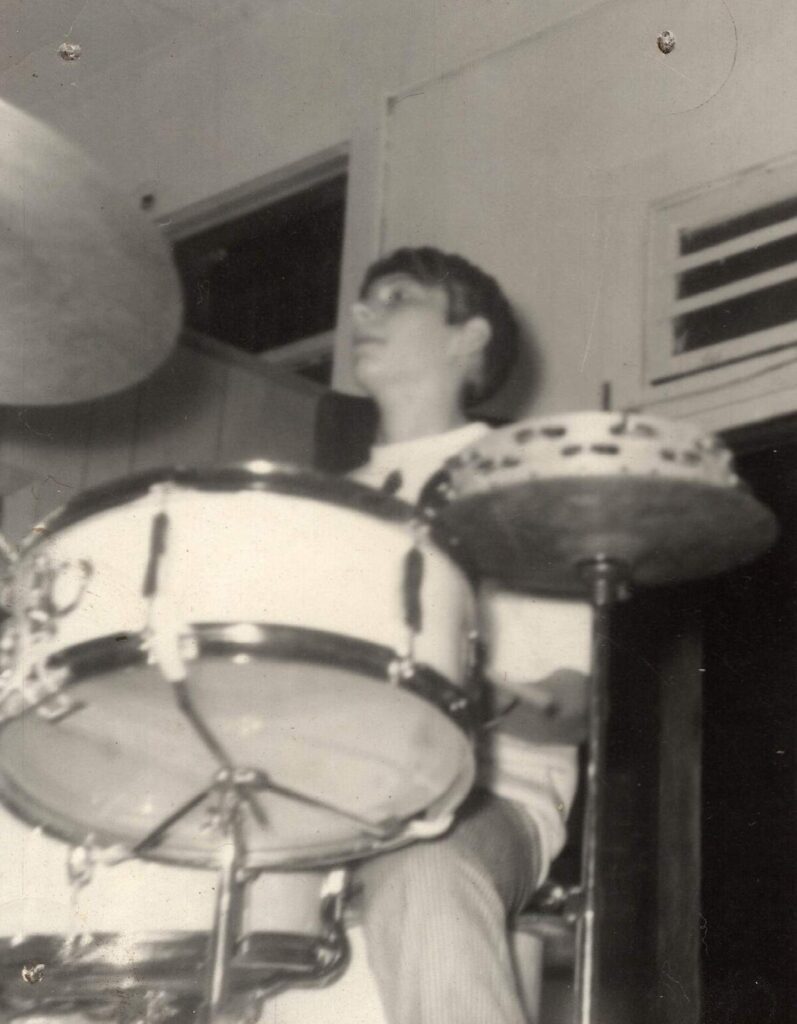

My older brother John started the J-Walkers in 1965 with his best friend DJ (David Johnson). They were fifteen. John played the drums and DJ played guitar. Jim Clapper played lead guitar, and Ted and Charlie Furry played guitar and organ. They would rent out an empty building downtown or in a neighboring town and play dances. They made pretty good money for high school kids, maybe $12 each, playing what they now call ‘garage rock’: ‘Louie Louie’, ‘Dirty Water’, ‘Wipeout’, ‘Little Red Riding Hood’, ‘Satisfaction’, ‘Hang On Sloopy’ — all the hits. DJ had a great voice and looked a bit like Elvis.

Was that as early as 1965? That’s wild.

It was great. I was only eight or so, but I would go to the dances to watch them. They played at the back end of the room, with the back double door open to the alley. There were benches on either side of the room, which was full of kids dancing. But I never connected them to the larger music world, and I never thought about playing myself at that point either. They only broke up when Jim and Ted got drafted and went to Vietnam. Luckily, they both came back.

What eventually led to the formation of Phantasia? Was it a natural next step, or something sparked the shift?

I think Phantasia started because my brother John needed some action. After graduation, most kids left town. But the old man ran afoul of the law. After funneling most of the family business’s profits into his illegal schemes, he got busted and sent to prison. So when John graduated high school in 1968, he had to stay home to help Mom and the younger kids keep the business going. He was stuck.

DJ was a year behind John and had started playing with Bob Walkenhorst (BW) when they were still in high school, DJ on guitar and BW on drums. They were from totally different backgrounds. DJ’s grandpa had been what they called a “river rat” — poor folk who lived by the river, off the grid before there was one. His dad grew up on the river and only moved to town when he married DJ’s mom. He died when DJ was a young boy, so DJ lived with his mom on the other side of the tracks.

BW was about four years older than me and the second of three sons. Both his mom and dad had been divorced with prior families and had started anew together. BW’s dad was a carpenter and jack-of-all-trades, and they were steadfast Lutherans. They were a clean-cut family, and I spent a lot of time at their house with BW’s younger brother Rex, who was my best friend at the time.

DJ and BW both sang, so John talked them into getting a band together, with him playing drums and BW switching to guitar. Jim Clapper had returned from Vietnam by now, so he joined on bass, and they started playing dances. The first was at an ice cream social at the Lutheran church. BW had added a pickup to his acoustic guitar, so they had a bit of a folk-rock sound at the start, especially on songs like ‘The Weight’. They’d only play school dances or street fairs in Norborne. Most of their gigs were at the VFW Hall in Carrollton, ten miles away. But they’d play schools and other American Legion Halls within 30 to 40 miles of our town.

Did you have a clear idea of the sound you were after when you started out? Or was it more about chasing a vibe and seeing where it took you?

I think that was all dictated by the equipment they had and the songs they covered. They updated their set with more late ‘60s, Woodstock-era material. Steppenwolf, Creedence, the Stones — stuff like that. They were just playing things they liked. They changed along with their audience.

What kind of gear were you working with? And how’d you even get it all — saving up, hand-me-downs, borrowing from friends?

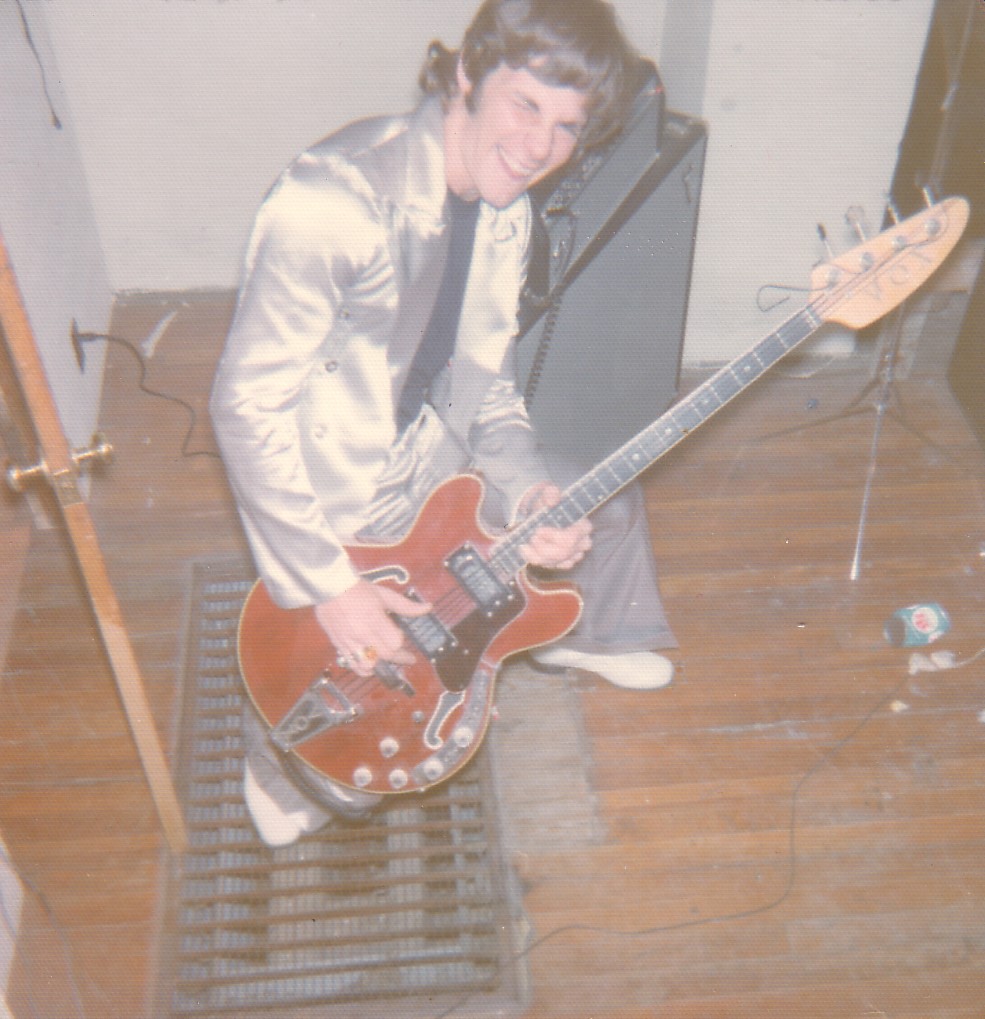

Before the old man got busted, he’d stashed army ammo boxes full of cash here and there. John found one in the basement with several thousand dollars, and that’s how he got the money for the equipment. They got Fender Bandmaster and Bassman amps, the Rickenbacker guitar that BW would play, and the Vox bass. DJ played a Harmony guitar he’d gotten from Clapper back in the J-Walker days. For effects, DJ had a Fuzz Face distortion box. BW had purchased a small P.A. system that an earlier band called the Litter Bugs had used.

Who were the original members? The first lineup was around ’69, right?

That’s about right. It was DJ and BW on guitar and vocals, Clapper on bass and backing vocals, and John on drums.

Did Phantasia ever play out live before the record? Would love to hear about any early shows.

Absolutely, but always only as a cover band. The only originals they ever played were ‘Carroll County Queen,’ where DJ and BW would do a call and response on the chorus. They did ‘Give Life Another Try’ a couple times. ‘I Talk to the Moon’ was a real popular slow dance. But these were all dances, and the floor was always full of high school kids.

They/we were never a jam band. They played the songs like they were on the record. The only extensive soloing I remember would be when they’d stretch out on ‘Susie Q’ or ‘For What It’s Worth.’ They played school proms and VFW halls.

The band would practice in the back of our family factory, and I just hung out all the time. I went along with them to as many of their dances as I could and eventually ended up sitting at the front of the stage, back to the audience, playing their lights on a little keyboard that I had constructed. I had front-row seats for one great show after another. I was still in junior high, but some girl would always come up and sit beside me at the light board. I just remember it was a great time and they had a blast.

Was there a central idea behind the songwriting for the album, or did the songs just come out of whatever you were going through at the time?

All the lyrics were John’s. Like I said, he was pretty unhappy to be stuck in Norborne, and he spent a lot of time writing poetry. His bedroom window let out onto the roof of our small back porch, and he would literally sit out there under the moon writing. He pretty much pestered DJ into writing music for them, and those were more straight-ahead rock songs. BW was more prolific than DJ was, but most of BW’s songs were acoustic and folk-based. BW could fingerpick, which meant the band could play James Taylor’s ‘Fire and Rain’ and José Feliciano’s ‘Light My Fire’ at the dances. So the songs were John’s words — filtered through two different voices and styles.

Can you walk us through the decision to do a private press? Was it just to get something down on tape, or were you hoping to catch someone’s ear — radio, labels, anything like that?

I have no idea. Stuff like that was way over my head. I think I only found out about the Phantasia album after it was done. I hadn’t even heard all the songs — just the ones they’d practiced at the factory. It had to be John or BW who had the idea. The money probably came from John, so I’m pretty sure he was the instigator of doing it.

Were there any shows tied to the release? Did you feel like you had local support, or were you kind of off in your own corner making something nobody else was doing?

I don’t recall that they did any kind of dance or show to celebrate the album. It was more just for them and family and friends. It felt like it was just there, but no one knew what to do with it. BW could tell you more about it than I could, by far.

Where was the album recorded, and what do you remember about the sessions? Any stories or weird moments that stand out?

They recorded it at Damen Recording Studios in Kansas City, MO, and the owner, George Damen, produced. They all spoke very highly of George over the years. They did it in a day. DJ’s songs were done live. BW’s had more overdubs. I think John and BW went out back halfway through and smoked a bit of a joint. BW played the tympani parts.

Would you mind sharing a bit about each of the tracks on the Phantasia album? Whatever you remember—moods, meanings, how they came together:

Well, just my thoughts, as I had no hand in any of them. As I said, they were all John’s lyrics, which were very influenced by Peter Sinfield of King Crimson. He also read a lot of Edgar Allan Poe and Sherlock Holmes, which you can hear in how he phrases certain things. DJ wrote the music for ‘Give Life Another Try’ and ‘Transparent Face.’ BW wrote the rest.

‘Transparent Face’

John’s “freak out lyrics.” I remember hearing DJ sing this, just playing the rhythm on an acoustic guitar. (He was maybe the best rhythm player I ever heard— incredibly strong.) Just the chords sounded so great. BW’s guitar riff was added in the studio. It was a surprise when I heard that on the record.

‘Winter Wind’

Pretty much a BW solo piece, and a good example of his finger-picking style. One of my favorites from the record.

‘I Talk to the Moon’

I was the first person John played this song for, at home. He took it to BW, who arranged the guitar part. It’s one of the few things I can still play on guitar. This version was much faster than I ever remember them playing it live. The bongos were also a surprise. It was the one song from that time that stayed in their live shows, up until the very end.

‘Chasing Now the Flying Time’

The different solo and full-band portions of the song are an obvious Crimson influence. This is BW playing some kind of wooden flute-like thing on the instrumental bits.

‘Featheredge’

A pretty song, BW on piano.

‘Genena’

John had a long-time crush on one particular girl. Her name wasn’t Genena, but this was one of many songs written about her. The first half is solo BW. It was DJ’s idea to add the extended guitar instrumental as a second part. To me, the Latin feel on that shows a Santana influence. It’s pretty much the high point of the record, for me.

‘Willow Creek’

Another solo BW piece, with some cool percussion elements and BW’s falsetto. I think songs like this are why people have referred to the album as ‘psych folk.’

‘Give Life Another Try’

This was really one of DJ’s best songs, if not the best. Really powerful live, with DJ belting out the chorus as BW and Clapper sang response. The ultra-fast coda, with DJ’s fuzz lead running over BW’s chord flourishes, led up to the big “Grand Funk ending.” Awesome. They had a couple other more acid-rock songs like ‘Death to the Derelicts,’ but John thought putting them on the album would not go down well with BW’s folks. They also didn’t include ‘Carroll County Queen’ because John was still hoping to reconcile with the girl in the song.

How many copies were pressed in the end?

Twenty-five. A copy is worth well over $4,000 at this point.

There’s some confusing info floating around online—releases listed as ‘A Psychedelic,’ ‘I Talk to the Moon,’ ‘Walkenhorst – De Pugh’… Can you clear up what’s actually what?

Gladly. ‘Walkenhorst–DePugh’ was a one-sided 33 1/3 record that John and BW did in (I think) ’71. Phantasia as a local dance band had kind of petered out, and BW was going to be going to college soon. I think John wanted to try pitching the songs themselves, not the band in particular. So, BW played and sang everything, including drums. (He was very good, and you can hear the influence of Michael Giles, the King Crimson drummer, here and there.) Of the four songs, three had been on the Phantasia record. ‘I Talk to the Moon’ was slower with a more acoustic feel, ‘Winter Wind’ and ‘Chasing Now the Flying Time’ were much cleaner sounding, but not much different from the originals. ‘The Saddest Song I Know’ was the only new song, with an extended flute coda that repeated the refrain from ‘I Talk to the Moon’. Anyway, BW and John tried pitching it in Nashville, but nothing happened, and BW took off for college.

‘A Psychedelic’ and ‘I Talk to the Moon’ were LP compilations that John put together and licensed to the Ton Um Ton label in Austria much later, in the early 1990s. They consisted of tracks from both the Phantasia and Walkenhorst–DePugh albums. ‘A Psychedelic’ focused more strongly on the DJ songs and used three Trizo 50 songs, without crediting them as such. That one was also issued on CD, with another seven Trizo tracks. The Phantasia and W–D tracks were dubs from the original vinyl copy, but John had remixed the Trizo 50 tracks from the original 4-tracks, and those were the mixes used for the German World In Sound release that he licensed ten years later in the early 2000s.

So before Trizo 50, there was Phantasia. Can you talk a bit about that transition? How did those early sessions shape the music that came later?

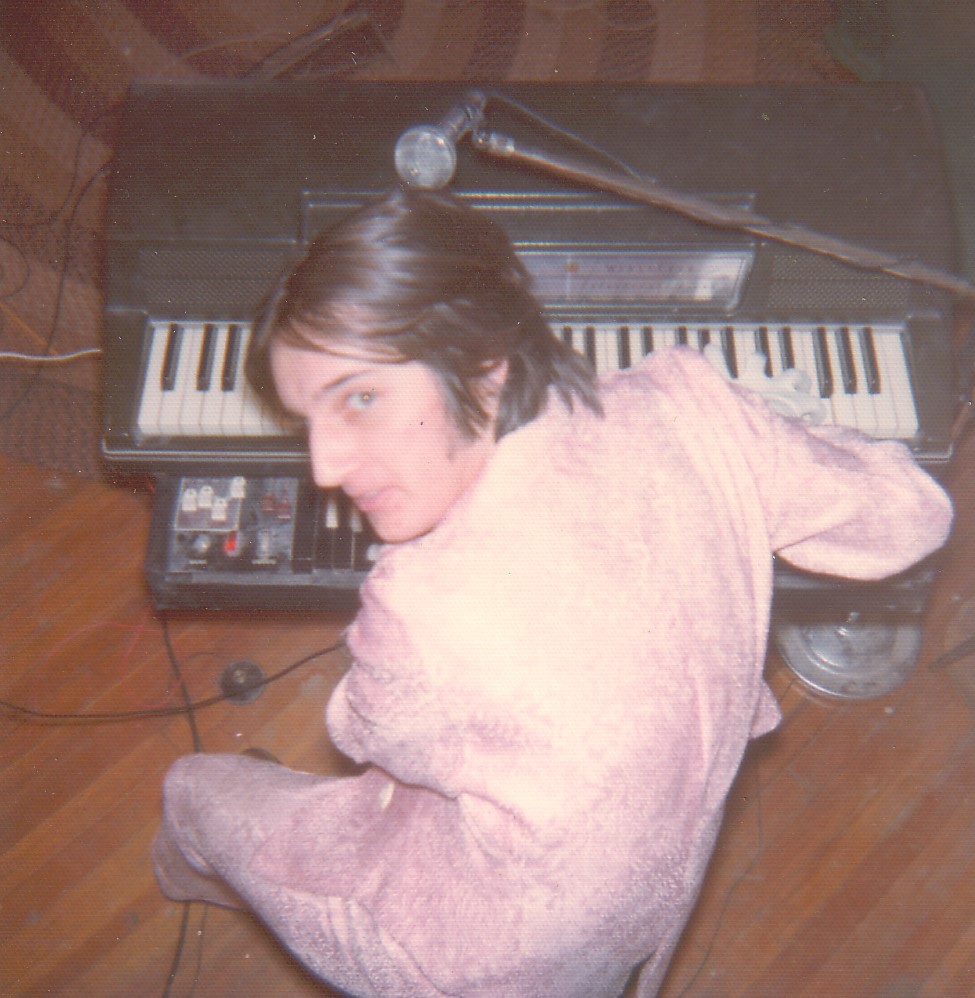

After the W–D album and John and Bob’s trip to Nashville, things kind of tapered off. BW left for college. He’d come back for a dance now and then but it was pretty quiet for about a year. Then in the fall of ’72, I was entering my junior year of high school and out of nowhere, John asked if I wanted to join the band on keyboards. I’d honestly never even thought about it.

Looking back, I strongly suspect that Mom pressured John to bring me in to keep an eye on me. I was about to turn 16, which meant I could possibly kill myself in a car crash drinking and driving on the gravel roads that encircled the town, because that kind of thing happened. I’d already learned to drive by agreeing to take six months of piano lessons from a fellow student who lived out in the country, if I got to drive our ’69 Impala there and back on my own. That all started because we’d inherited my mom’s upright piano and I was starting to noodle around on it.

So, John asked the guys and they said OK, and I was in the band. We went to the Vox Box in Lexington and got me a Wurlitzer electric piano like the one Ian McLagan played in the Faces. DJ sat down with me at the factory one night and taught me about forty old songs from the J-Walker days. We played our first gig at the Norborne Legion Hall as a way to raise money for a new Fender Super Reverb amp for BW, since I was taking the Bandmaster. The dance bombed, and I think Jim pitched in the money to get the amp. Then we played the high school Yearbook Party, a couple other dances, and some really wild, fun New Year’s parties at the swimming pool building.

I think my joining the band kind of reinvigorated them, because the piano meant they could play songs like ‘Lady Madonna’ or ‘Feelin’ Alright’ by Joe Cocker, or ‘Imagine’ or ‘Rockin’ Pneumonia & the Boogie Woogie Flu’. Plus I was suggesting newer songs to play, like T. Rex or Bowie. And I think BW liked getting a bit of extra cash while he was still in college. So, things were getting more active. By the start of ’73, we really hit our stride. We were usually playing two 2-hour sets and making $150–$300 total.

What made you want to revisit and license the Phantasia material in the ‘90s? Looking back, do you see that record as an important part of your musical story?

That was all John’s doing. It was a creative outlet for him, and he was always looking for a way to make some money. I’m told that those Ton Um Ton records were well received in the European psych community. They probably raised the public awareness of Phantasia, much like the unauthorized use of the Trizo 50 track ‘Graveyard’ in the 1998 ‘Love Peace and Poetry’ compilation, which was basically a bootleg dub from the original vinyl. It was also in the late ’90s that John licensed the ‘Phantasia’ and ‘Walkenhorst–DePugh’ albums to World In Sound of Germany. They did a wonderful job and probably did as much as anyone to put Phantasia on the map.

Their reissue of the Trizo 50 material did not fare so well. Instead of simply issuing the demo album as it was, John insisted on an impractical multi-disc release, and the compromise was a ‘Vol. 1’ release, with a ‘Vol. 2’ to follow. But John had added new audio elements to some of the tracks that I did not like, and left the sequencing of the album to the label, resulting in an odd mish-mash of badly mixed tracks. It failed to sell enough to warrant a second volume. Since the liner notes for ‘Vol. 1’ only dealt with the Phantasia days, the story of Trizo 50 was left untold, and half the original album unheard.

So how did Trizo 50 come about? What’s the backstory there?

Well, as I was saying, we’d had some profitable shows with the new lineup over that New Year’s. Early 1973, BW brought up the idea of getting the 4-track recorder. John came to me and said the plan was to write and record a bunch of new songs, press a record, and try to get a record deal. DJ was game, but Jim didn’t want to record — he liked playing live, period. So, we brought in a pal of John’s from Carrollton, Jim Bell. He played the same Vox bass that Clapper had been playing. He was a fun guy to be around, and he looked good on stage.

But we needed $2,000 for the recorder. We worked up a new set and played almost constantly that summer to make that money. There was a burned-out building in town that used to be a beauty parlor with my childhood doctor’s office in the basement. It had been totally destroyed except for the front room. There was no running water or heat, but there was still electricity. John bought it for $500, and we started building our recording studio in the front room. It wasn’t finished when the recorder arrived in July, so the first seven songs were recorded in another empty storefront we’d been rehearsing in.

Up until then, there had really been two Phantasias: the rocking live cover band at the VFW Hall, and the trippy introspective band that wrote those songs and made that record. In a way, Trizo 50 was the fusing of those two creative impulses. By 1973, the Phantasia record felt like a completely different era, and it was a conscious decision to write rock songs that could get on the radio. I’d started writing music to John’s old poems in the fall of ’72, but we only started writing the Trizo 50 songs in the spring of ’73. I was 16 at the time; the other guys were 20–23. Four of us could sing and write songs. While John was always pretty much the leader of the group, we were pretty democratic when it came to the music — kind of like the Moody Blues in that sense. That accounted for the variety we had.

And the name — what’s the deal with ‘Trizo 50’?

We’d been recording for a month or so, and it was pretty obvious that ‘Phantasia’ did not fit the new music we were making. Terms like “power pop” and “glam” really hadn’t come into use yet there in our little world, but we were influenced by that and were looking for something that felt like “now.”

We were sitting around the factory one day talking about it and throwing out names. BW suggested The Tomatoes, and I was intent on shutting that down, so my mind was racing. My eyes were scanning the room and fell upon a box of injectable vials on one of the shelves that was labeled ‘Trizo 50.’ It was used to add contrast to pig x-rays. I blurted it out, and everyone just said, yeah, that’s it.

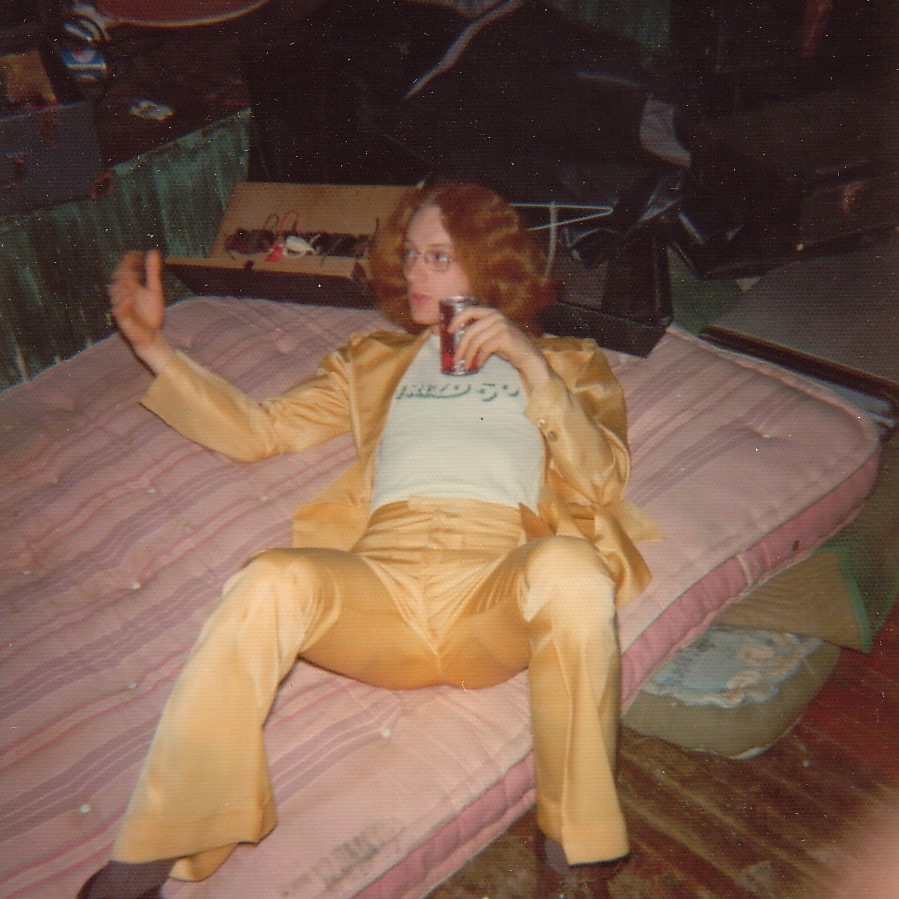

That’s really when ‘Trizo 50’ started. It put a concept into our minds of the band we were going to be. That led to the sateen outfits that we started wearing on stage, which JB’s mom made for us. The name helped cement our new identity in our own minds and helped our sense of purpose as we cut way down on the dances and mostly kept recording through November to finish the album.

You did another private press for the Trizo 50 release, right? Would love to hear about that process. How many copies?

We’d recorded thirty songs and we picked twelve for the record. Each band member voted for their favorite dozen, and the songs with the most votes went on the record. There’s been a fair amount of debate over the years about that process. Should JB have had a vote even if he didn’t write any of the songs? BW and DJ had started writing songs on their own. John was writing songs more with me than with them, so the two of us formed a voting block, and I ended up singing eight songs on the album. It’s only when we took the tapes down to Cavern Custom Recorders in Kansas City that we learned there was room for three more songs. That’s when we added a third DJ song (‘Why Do You Do That to Me’), along with ‘I Talk to the Moon’ and the ultra-short ‘Naughty and Nice’, which BW sang. Even with that adjustment, I feel there were some tracks that didn’t make the record that were better than some of mine that did. We pressed 100 copies, with a crack-and-peel front cover. It took about four months for them to arrive, which was a big drag.

The album was partly recorded on a 4-track reel-to-reel, very DIY. Did those limitations help or hinder the creativity?

It was recorded completely on a TEAC 2340 4-track reel-to-reel. The basics were pretty easy, and the sound was great on a first-generation take. It could be a lot of fun, and we often surprised ourselves. Each session started with whoever wrote the song teaching it to the band. We would record the instruments on two tracks, and then the vocals on two tracks. But if we wanted to add anything as an overdub, we’d have to mix existing tracks together and record them on the now-free track. Every time we did this, the fidelity dropped. But over the 18 months we were recording, the TEAC broke down several times, each time taking weeks or months to get repaired, during which time we had no dubs of what we’d recorded to listen to.

The biggest hindrance didn’t come from the recorder though. Theoretically, we should have had my entire senior year to make the album. BW was staying home from college that year to commit to the record. But the old man got paroled from prison in April just as our grand plan was taking shape. After five years of fun and freedom, he was back and the curtain came down. His obstruction was unrelenting. He and John struck an uneasy truce, but we now had to scrape and claw for everything we wanted to do. I was frequently grounded and unable to play on several sessions. We were constantly under duress, and the tension spilled over into the band. What should have been a wonderful creative scene turned at times into a hurried chore, and there was a mounting pressure to just get it done. As a result, we never spent more than a night or two recording a song and very rarely re-recorded one to make it better.

There’s a real sense of place in these songs — from high school practice rooms to LA streets to the Kansas City scene. Do you feel like those places found their way into the sound and lyrics?

Well, L.A. didn’t — we hadn’t been there yet. As far as Kansas City, it was like another planet. Although the band did make the trek down there for some concerts. My first was Van Morrison at the Cowtown Ballroom. The other shows were at Municipal Auditorium. We saw The Moody Blues with Trapeze there, and a package show with The Searchers, Billy J. Kramer & the Dakotas, Wayne Fontana & the Mindbenders, Gerry & the Pacemakers, and Herman’s Hermits. Also, from seats behind the stage — Elvis. I think music is primarily subjective, so each person is going to feel a different sense of place reflected back to them in the music. Songwriting is mostly just about getting everything to work together to where it sounds like what you want.

“The only “effects” we had were the guitar fuzz boxes and a 1966 Fender reverb bar unit.”

Could you talk us through the tracks on the Trizo 50 album? Even just a memory or feeling attached to each one would be amazing:

Sure. The only “effects” we had were the guitar fuzz boxes and a 1966 Fender reverb bar unit. Four of the songs (‘Take,’ ‘Wanna,’ ‘I-I’ & ‘Everytime’) were recorded in the practice space. That was a big room with a tall ceiling and we put old mattresses around the drums and anything we weren’t plugging direct into the recorder. There’s a different sound on those from the tracks recorded in the studio we built. That was a smaller room where the piano would be mic’d, picking up some sound from the guitar and bass amps, which were plugged in directly. The drums were in a separate booth, and there was a small “control room” with the recorder, and we recorded the vocals in that.

‘Take A Ride’

This encapsulates so much about the band. It was the third song we recorded and there was never any question that it would open the album. The opening line was DJ’s idea. He and BW wrote the music. The combination of BW’s rhythm and DJ’s riff was something we used several times. It became part of their style. The harmony guitar part on the solo was a mistake. DJ meant to double track it in unison but just hit the wrong notes. It was a lucky mistake. BW sang on the recording originally, but John — who had helped finish up the lyrics — recorded his own vocals over BW’s. I didn’t play on the track, but I sang (badly) with John on the final chorus. So there’s a bit of a troubled history to the song. For my part, I was never happy with the ending. After the powerhouse intro and the awesome Fripp-like solo, it seemed to just limp to a close like a wounded dog. So, when I remixed the track for the new release in 2023, I took snippets of DJ’s solo and layered them over each other on top of the ending vocals. To me, it sounds a bit like a horn section and gives the song the ending it deserved.

‘Rock Me Roxie’

I think this was BW’s best track, and one of our top five. It was his song, and he had the arrangement worked out. BW played the lead parts while he sang, and DJ’s spooky riff adds a heavy element to JB’s boogie bass line. I played sax and DJ played trumpet for the middle solo. We all sang, and John always took the highest falsetto harmony — and the werewolf screams. BW was obviously shooting for T. Rex and totally succeeded. A real high point.

‘I Wanna Be Loved By You’

One of our best recordings. DJ wrote this, with John’s help on some of the lyrics. DJ had BW play the acoustic while he added the electric barre chords on the chorus. It was the last song we recorded in the practice space. I manned the recorder for that one and sang with the group on the backing vocals.

‘Get Another Girl’

That was my song, with a couple of lines from John. BW and DJ played their rhythm/riff combo again, but there was a lot of interplay with JB’s bass line so it’s a very interesting track on its own. DJ didn’t feel like he was that good on trumpet, so a friend from high school played flugelhorn along with my sax for the end part. I remember DJ saying one time, ‘You’ve got a nice voice — why do you want to scream like that?’

‘Why Do You Do That To Me’

I wasn’t even in the studio for this one. It was all DJ’s song — the instruments live on two tracks, with the vocals double tracked on the other two with the solo overdub. Great sounding record. DJ didn’t write that many songs, but they were all perfect on arrival. This was our most Beatle-like track.

‘Graveyard’

This was the outlier on the record. It was the first track we recorded in the studio we’d built, so I think we were feeling like stretching out a bit. It was the first use of the piano, which was tuned a half note flat. The guitars and bass had to tune down to match. There’s an entirely different sound to the tracks that we used the piano on. Also, despite our pledge to only record ‘Rock Hits,’ this was an old poem of John’s that I had written music to. The lyrics are much more like a Phantasia song than the rest of the record. It was longer, had multiple parts and a time change, and everyone worked really hard on it. Because of the organ and acoustic guitar overdubs, I sang lead with BW and DJ singing backup on just one track. They really had a good sound together, and I’d have them back me up on several songs like that. The ending was a complete accident, when a bit of an earlier take kept playing after we’d finished the song. It’s pretty much regarded as our best effort.

‘Laugh About It’

This was all my song. I wrote the guitar riff on the piano, but didn’t play on the song myself. Just as there were several DJ and BW songs that I didn’t play keyboards on, there were several of mine that I didn’t play on either. We (and I) still thought of keyboards as an optional instrument — not meant for all songs. We recorded this song twice. Originally it was the fourth song we taped, but we recorded this superior version just before we finished the album up. The lead guitar solo was the same one BW played on ‘Cold Turkey’ when we did that song live. The track faded out on the original demo LP, but for the reissue I let it run to the end as the vamp got looser. There were only three fades on the album because we thought fades were musically lazy, so I was glad to let the track play out.

‘I-I’

This is the second side opener. It was written together on acoustic much like ‘I Wanna Be Loved By You,’ but this one may have been more at John’s instigation. He wrote it with DJ one day at the factory while I was watching. We may have played it live a couple of times, but I don’t remember for sure. DJ dropped his rhythm part once BW started coupling the bass line riff with his rhythm. I ran the Wurlitzer electric piano through a distortion box — it was only the second time I actually played an instrument on a track.

‘Everytime’

This was the fifth song we recorded. These were John’s lyrics about his new girlfriend and he was keen to record it. The problem was that I’d written the music on the acoustic piano, but we didn’t have that in place yet. Also, the old man was severely restricting my time with the band during that time. So I went in one night, taught the song to the guys, and they arranged and recorded the guitar parts and rhythm section after I left. The next night I sang my lead vocals and BW and DJ recorded the background vocals after I left. It didn’t sound anything like I’d imagined, but it was unique and felt like our first accomplished recording.

‘Ride Me’

That was all my song, and it was all about my teenage horniness. We recorded the track live in much the same setup as ‘Graveyard.’ I overdubbed the ‘moog’ solo on a Metronome that I borrowed from the high school. It was really fast, with full backing vocals and a drum breakdown chorus. To top it off, I had DJ record a backward guitar part that weaves in and out. Maybe not the cleanest record we made, but the most energetic.

‘Dream Girl’

This was another case of John’s lyrics and my music. I was really hoping to have a great ballad to my credit like ‘I Wanna Be Loved By You’ or ‘I Talk to the Moon’ were for DJ and BW. I don’t know that ‘Dream Girl’ ever made it. I wasn’t happy with this at the time and was much happier with the recording John and I made after the guys left the band. I appreciate it more now than I did then, mostly because of DJ’s playing and the low background vocals. When I mixed it for the new release, I deleted my lead vocals on the chorus that follows the second verse in order to showcase those two elements more.

‘Naughty And Nice’

This was mostly John’s lyrics and BW’s music. As with ‘Roxie,’ BW had a great arrangement. He worked out the harmonized guitar riffs and the fabulous “Do it do it do it” background vocals with DJ. It was mostly guitar with just a bit of organ. It was a fun track, with three verses, choruses, a bridge, and a solo—all in 1:38. The track just defied the laws of physics.

‘Guitar Girl’

John’s lyrics and my music, another song I chose not to play on. I loved DJ’s riff and BW’s lead guitar part, but I never liked my vocal and I wouldn’t have included it on the album. In re-mixing, I stripped out a vocal line from the end of each verse to feature the guitars more. I’m quite happy with it now.

‘I Talk To The Moon’

The only Phantasia song to last through both bands. It had become a favorite slow dance at our shows, and we recorded it feeling we needed an extra ballad. We did not include the electric piano part that I had added for our live shows, so this is very representative of what it sounded like originally. It’s the one song on the new release that is dubbed from the original vinyl. BW’s original vocals no longer exist on tape, as John had me record my vocals over them after BW left. I regret that.

‘You Make Me’

This was all my song, another one about my teenage sex life, but the main riff is all BW. He used the same riff about ten years later for his song with the Rainmakers, ‘The Other Side of the World.’ The lyrics are pretty embarrassing at this point, but some people seem to like the track a lot. I employed a trick with the electric piano by playing double bass octaves through a volume pedal. It sounds like a big bassoon in the intro. BW once noted that this song contains two key signatures. That was news to me. I could write two kinds of songs—those based on basic rock chords, like ‘Get Another Girl,’ ‘Ride Me,’ or ‘Laugh About It’—or songs where the chords just wandered, dictating how the melody would go—like with ‘Graveyard,’ ‘Dream Girl,’ or this one. BW and DJ may have known what they were doing, but musically I was pretty naïve. I still am.

At the end of the day, we tried to sequence the record in a way that made sense. But it still was, basically, a sampler.

You’ve said John was the lyricist before Trizo 50, and that many songs are based on his poems. How did that shape the music’s mood and themes?

Well, I’ve written about how John’s poetry was the emotional foundation for the Phantasia album. With ‘Graveyard’ and a handful of other songs, we would sometimes reach back to that source for songs even though they wouldn’t be Rock Hits. Partly because we’d grow weary of striving for pop and feel like doing something a bit more meaningful. When John started writing lyrics for Trizo songs, he made a deliberate effort to write as simple a lyric as he possibly could, and sometimes we just needed a break. In terms of the band, though, it was a big change when John ceased to be the sole lyricist for the band.

Did you play out much with Trizo 50? Get any airplay?

We never ever played live under the name Trizo 50. We continued playing just a few dances after we started recording, but Phantasia was our brand and we weren’t going to confuse people with a new name. We only ever played our new original material twice—once at the Grain Valley prom in the spring of ’74 and maybe another time. There was an ongoing debate about whether we should try to make it by playing live shows or try to make it by making a record. Neither was really a viable option for us, considering our locale and circumstances.

The only time I heard us on the radio was that summer. John and I were riding around in the country and ‘Graveyard’ came on the radio. One of the band’s fans, Jery Gay, was a DJ on KAOL Carrollton radio, and she played it. That was a marvelous moment. (I’ve garnered three times as much airplay for the re-issue!)

What about the single ‘Take A Ride’ / ‘Bye Baby Good-bye’—how did that come together?

You can file that under “Be careful what you wish for.” By the time the records arrived in mid-March, we were already having a lot of internal problems due to the stress my family situation was putting everyone under. On top of that, John’s new girlfriend had turned into his new wife with an unplanned baby. DJ and JB both had wives and kids. When the demo record came back sounding so lousy, I really figured it was over for the band. We were spent.

And then there was an ad in the Kansas City Star—a talent scout from Nashville. We played him the record, he loved it. He had us come to Nashville to make that single with all sorts of promises. Technically legal, it’s a scam that continues to this day. We paid $1,000 so we could drive down there and spend three nights in a hotel so we could spend two hours in a studio making that piece of shit. It was a miserable experience. When we got the box of 45s—and nothing else—we knew we’d been screwed. A few months later, we saw the whole operation on an episode of “60 Minutes.” Almost all of those 45s were destroyed in a fire (yes, a second one) in the studio building the following year. Good riddance. BW, DJ and JB all left the band after that. It was like getting a kick in the ass on your way out the door.

After that, the band was done. John and I kept recording, and all of them came back at one time or another to play on a track or two, but BW was going back to college and DJ was soon playing with another band. I graduated high school and John and I kept recording songs when the TEAC wasn’t broken down. We re-visited Phantasia period lyrics and hit our stride with tracks like ‘Surrealistic Images’ and our remake of ‘Dream Girl.’ I learned to pare down the arrangements to avoid overdubs and, of course, had to have arrangements that were within my limited talents.

Songs like ‘Carroll County Queen’ and ‘Hey Girl’ have you and John trading vocals—it sounds like such a personal dynamic. How did that back-and-forth shape the storytelling?

With ‘Carroll County Queen’ I was trying to recreate the back-and-forth vocal that BW and DJ had when performing that song years earlier (in a much different rhythm). Those were both recorded after the other guys left the band, and John and I would split the vocals on a couple of those. Basically, it was a way to get more variety wherever we could. Being brothers, John and I could sound very much alike, so we could have a very nice harmony sound at times (for example, ‘I Wish You Were Mine’). We had several songwriting dynamics. The first was me writing songs to his poems or lyrics. The second was him writing a full portion of a song, and me writing the other (for example, ‘I’m Alive’). The third was when John would add a line or two to a song I’d written—or I would polish up the music he’d written for one of his songs. It was all about how much of the song you brought to the table and what was needed to make it whole.

Both Phantasia and Trizo 50 have this bittersweet, haunted feeling to them—almost like old photo albums set to music. How do those early recordings hit you now, all these years later?

There was a long time (decades) that I didn’t listen to or think much about any of that music. My life had moved on and out and there was much about that time I was glad to forget. I was having too much fun being dazzled by Chicago and the big world I’d heard about but never seen. I only had a couple cassettes that I’d dubbed down long ago to listen to every once in a great while. It was really only when John was licensing the material out again in the late ‘90s that I started to revisit that music. Remixing the tapes myself has been a deep dive. It’s been very intensive and emotional. John passed away in 2015, yet I’ve heard his voice more in the past few years than I had in ages. But even with those long gaps, the music doesn’t hit me any differently. They’re like old friends—you know their flaws and accept them.

It seems like the line between ‘band’ and ‘duo’ was always fluid for you. How did that affect how the songs came together in the studio?

After the other guys left the band, I spent all of 1974—and years after—thinking that John and I were still “the band.” At that point, he was playing the drums and I was playing everything else. A couple of the last tracks were really just me. But as far as I was concerned, everything on those 4-track tapes was Trizo 50. John and I continued to write together through the end of the ‘70s, but the songwriting dynamics stayed the same.

You had big dreams, trips to LA, brushes with the industry, and some rough letdowns too. How did all of that shape how you saw yourselves as musicians?

Yeah, the end of ’74 was pretty crummy. We’d severed ties with the old man, so I was living in the studio. John’s wife was filing for divorce, so he was hiding out at our Grampa’s place to avoid a subpoena while I finished the last tracks we wanted to record. We’d had to wait until I turned 18 that November until we could split, so in January ’75 we left the Missouri winter and drove to West Hollywood, where we spent a month hawking our tapes and never even going to the beach. It was a bust, we ran out of money, and came back to Missouri.

Even though our dreams crashed and I never really played with a band again, I somehow did think of myself as a musician until fairly recently. I understand now that musicians are people who continue to create and actually work for a living. Neither John nor JB ever played with a band again. DJ continued to play locally, often with Jim Clapper for years and years. They played hard country and got more crowds at the local street fair in the ‘80s than we ever saw.

Your later success—whether with The Rainmakers or solo projects—took a different turn. How do you look at your musical paths now, and what does collaboration mean to you these days?

BW’s band the Rainmakers was the only success to come later. I think you’d be hard pressed to find the thread between his ‘80s roots rock and the music he made with the band. But he was a hard-working guy with a strong healthy foundation who made the most of his natural talents. He still writes and performs solo in Kansas City now. He’d be the first to tell you that success is nowhere near the easy road you think it’ll be. As for collaboration, I only ever worked with the band or my brother, and that was over forty years ago.

“These new mixes feel like I’ve finally been able to give them their finishing touches.”

You’ve talked about remixing and revisiting the old tapes later on—was that a healing thing, or did it open up old feelings? How did it change your view of what you created back then?

First, listening to original tapes on the headphones literally puts you back in that room. You very much feel what’s going on there. I mixed the tapes chronologically, of course, so when they got to the point where DJ, BW & JB left the band, it was like hearing them walk out the door again. The difference in the recordings before then and after then was far greater than I’d let myself accept at the time. At times, it feels like there’s a hole in the middle of those recordings where the band used to be. These new mixes feel like I’ve finally been able to give them their finishing touches.

In the fall of 2023 I got to visit with all five remaining band members — Clapper, JB, BW, and DJ, a year before he passed. I hadn’t seen JB in fifty years. They’d all said they liked the album, but the high point for me was when everyone said how good they realized JB’s bass playing was — because they could finally hear it. That was my reward. That was the closure I was looking for.

There’s something really special about how personal this music feels—almost ghostly at times. What do you hope people take away from listening to it now?

As a virtually unknown band, I don’t know what preconceptions people bring to the record—if any. I know I get a lot of different things from listening to music myself—fun, strength, catharsis. We were aiming for fun. I think there’s something to the idea that music comes through people rather than from people. But you have to be in the right place at the right time to let that happen. It seems unlikely that a small town in the middle of nowhere would be that place, but we happened to be there and said yes, and the songs came.

Looking back from here—from high school demos and broken amps to decades-later reissues—what would you tell young musicians trying to put their art into the world today?

Don’t? Seriously, I have no standing as a musician to give one piece of advice. But I did redirect my musical interest into working for Alligator Records for the last 35+ years. I’ve seen how much tougher that business has become. Expect to work hard, don’t expect to succeed, and above all remember that expectations are a prison. Aim for fun, but when the fun’s done, leave. Don’t suffer for your art. I feel there’s something unhealthy about people paying to watch artists suffer.

Tell us about the truly stunning reissue of Trizo 50…

Well, thanks for that compliment. It took a LOT of time and cost more than I’ll ever make back, but here’s how it came about. Ten years ago, when John passed away, I took possession of the original four-track tapes. It had been a recurrent drag telling people I’d been in a band and not have something I felt good about playing them. I didn’t like the idea that the mixes that John had provided to WIS might be the last word on the music I helped make. So, a few years ago I just committed to it. I’d taken sixteen hours of sound engineering at Columbia College under Malcolm Chisholm (an engineer at Chess Records in the ‘50s and ‘60s), so I knew I could make it sound like it should. I wanted to give the other guys something they could be proud of too. I was lucky to have a graphic designer for a wife, which is why it looks as good as it does. I didn’t set out to press as many as I did, but the minimum on LPs was 250, so I had to. I ended up doing about the same on the expanded two-CD collection. After giving copies to the band, family, and friends, I put about 200 each out for sale through eBay/Discogs and then through my distributor, Lion Productions, LLC in St. Charles, Illinois. As of right now, there are about eighty LPs left for sale and maybe fifty CDs.

In terms of design and packaging, the LP got most of the love. It has the original cover, full-color inner sleeve with pages from my diary of the time, and a full-color booklet with a history of the band—and a download card. The two-CD set comes with a longer booklet and thirty-six extra tracks. Since we pulled mostly rock for the LP, there were a lot of moods and shades that were not included. There’s a second album’s worth of material by the full band—two of the best recorded after the album had been finished—plus all the tracks John and I recorded after the breakup. It’s the full story.

And lastly, anything we didn’t touch on? Any unreleased stuff, projects in the works, or gigs that still stand out in your memory? What’s life like for you these days?

I think I’ve released everything I’d want people to hear. There’s no projects in the works, though hope springs infernal that a clever Hollywood mogul could turn the whole story into a major motion picture, which I could then parlay into a madly successful board game. Barring that, I do have a couple of the home recordings I made in the ‘80s and ‘90s on my Robert DePugh YouTube channel. That channel also includes the 50 Year Reunion of the J-Walkers at Norborne High School. I convinced DJ they needed to do it in fall of 2015 a few months after John passed. Ted, Jim and DJ played, while BW added bass and I took the drum spot, which was the same kit John had played on both the Phantasia and Trizo 50 albums and all the dances. We only had an hour to rehearse so it’s pretty rough in parts but also a lot of fun. It’s all ‘60s covers, but you’ve got three original J-Walkers, three Phantasia members, and three original Trizo 50 members.

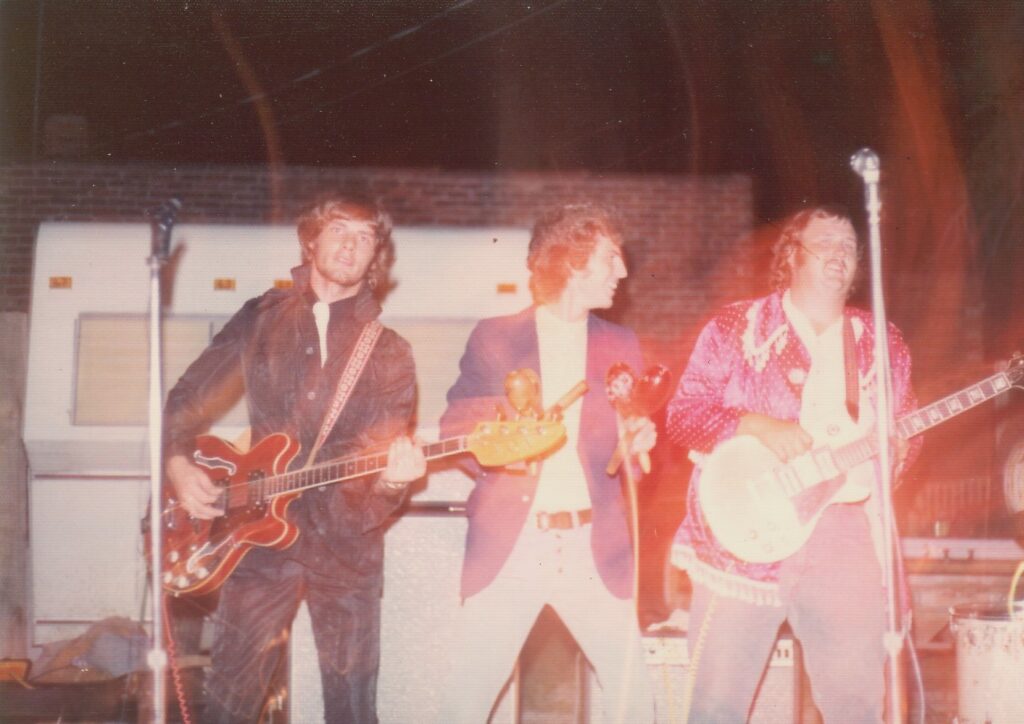

The gigs are kind of a blur for me. I was so intent on holding up my end. There was one homecoming dance where we ran out on the football field in our Sateen outfits during halftime. And a big gig at the VFW Hall where we entered the stage through a back window, wearing our Sateen outfits and stomping on plastic bottles of Johnson & Johnson’s baby powder because we didn’t have smoke bombs. The baby powder got on everything. Our big finale was ‘Hi Hi Hi/Jumpin Jack Flash/Satisfaction.’ The dances were way more fun than the recording, which was always pretty serious. I remember playing about six hours one night on the back of a flatbed truck out on a farm for a birthday party, and on a front porch for another one.

These days, I’m living a better life than I probably deserve, but I hope I give back to the people I share it with. I’ve been very lucky. I look forward to retiring at the end of next year. There’s much to see and much to fill the day. The reissue work will wind down. These records and CDs will end up on friends’ and strangers’ shelves, or in storage boxes, or flea markets. Maybe someone’s kid will discover one in their parents’ garage somewhere. I have no idea what they’d make of it, but it feels good leaving some dominos yet to be tumbled out in the world.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Bob DePugh (Trizo 50)

Thanks