Nduduzo Makhathini | Interview | Returns With Transcendent Suite ‘uNomkhubulwane’

South African pianist, composer, healer, and philosopher Nduduzo Makhathini recently released his third Blue Note album, ‘uNomkhubulwane.’

This transcendent three-movement suite continues Makhathini’s exploration of spiritual and metaphysical themes through music, paying homage to the Zulu Goddess uNomkhubulwane while delving into Africa’s history of oppression. The album features Makhathini’s trio—bassist Zwelakhe-Duma Bell le Pere and drummer Francisco Mela—whose intricate rhythms and vocal accents enhance the pianist’s spiritually infused compositions. Makhathini combines his roles as a Zulu healer and philosopher, using improvisation and ritual strategies to channel supernatural voices and transcend conventional musical boundaries. With ‘uNomkhubulwane,’ Makhathini creates an immersive experience that resonates with fans of spiritual jazz and South African music, drawing comparisons to the works of John and Alice Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders. The album’s first single, ‘Omnyama,’ showcases Makhathini’s signature use of hypnotic figures and vocal incantations, reflecting deeper themes of African creation stories and essence. Structured around three movements—’Libations,’ ‘Water Spirits,’ and ‘Inner Attainment’—the suite represents stages of collective mourning, restoration, and transcendence. The title track of the album, ‘Omnyama,’ invokes a genealogy of black origins through rhythmic contours and spiritual vocalizations, with water symbolizing creation and essence. The suite emerged from a “mother song” Makhathini received during his initiation as a healer, integrating ancestral memory and metaphysical guidance into his compositions. Through ‘uNomkhubulwane,’ Makhathini extends an invitation to humanity to explore new modes of humanism, emphasizing freedom, balance, and the spiritual legacy of uNomkhubulwane.

“To bring creation myths and primordial texts as a way to liberate the difficulties of being in the world”

The concept of transcendence seems central to your music, particularly evident in your latest album, ‘uNomkhubulwane.’ How do you conceptualize and express this notion musically, especially in the context of exploring spiritual and metaphysical realms?

Nduduzo Makhathini: The metaphysical lives in the realm of the ineffable; in other words, it cannot be spoken about. This challenge of language is what then results in sound as a way to sound out another world, another place. Essentially, I think of my work as a kind of “technology” that allows me to cite text from the spirit worlds. This is made possible by using what I call ritual strategies that allow me to transcend “performance” and deal with spirit voices. In that moment, I am able to transcend the limits and conventions of time and space concepts and realize the beyond.

Your album pays homage to the Zulu Goddess uNomkhubulwane while also addressing Africa’s history of oppression. How do you navigate the intersection of spirituality and socio-political commentary within your music, and what role does improvisation play in this process?

The core ideal is to bring creation myths and primordial texts as a way to liberate the difficulties of being in the world. Recently, there has been a turn towards indigenous knowledge systems as a way to activate collective memory beyond the catastrophes of black biography. For instance, history has produced an abstract affinity between blackness and forms of lack, while looking at uNomkhubulwane as a symbol points us towards abundance. If we view this through the lens of improvised music, it speaks to black aesthetics as a library of freedom and abundance. In this way, one is able to push back against normative paradigms that locate black aesthetics within positions of brokenness.

The use of spoken word and vocal incantations is a notable feature in your music, creating a unique blend of traditional African elements with modern jazz. Could you elaborate on your approach to incorporating these vocal elements and their significance in conveying the album’s themes?

The use of spoken word in this album is a kind of citation, an attempt to language an “elsewhere” — the place of gods. I deliver all the text as prophetic knowledge that is spontaneous. I believe that the word increases the vibrational depth of my sound. I am seeking to produce “ntu” (vital force).

The rhythmic complexity in your compositions, such as the use of time signatures and triplet feels, adds layers of depth to your music. How do you balance maintaining the integrity of African rhythmic traditions while pushing the boundaries of jazz improvisation?

I believe that the jazz DNA is African in the first place. Rhythm, therefore, is the philosophy of jazz; it brings jazz to its origin. Consequently, bringing African rhythms to jazz improvisation is somehow an organic process of re-membering.

The album’s movements—’Libations,’ ‘Water Spirits,’ and ‘Inner Attainment’—seem to follow a narrative arc, from collective mourning to restoration and eventual transcendence. How did you structure these movements to convey this journey, and what musical techniques did you employ to evoke each stage?

Yes, the suite has a chronology, moving from speaking the names of divinities to a place of birth, then mourning, and eventually reaching a place of transcendence. I mainly achieve this by turning to the text and again the word. These two become strategies to charge the sound with intention. This is achieved by way of surrender; in other words, improvisation departs from a kind of listening, sensing, and hearing the metaphysical voices.

Your experience as a Zulu healer has undoubtedly influenced your musical practice. Can you discuss how your spiritual beliefs and healing practices inform your approach to composition and performance?

I think of healing in very simple terms: healing as the realization of balance. Balance and flow are some of uNomkhubulwane’s characteristics that are invoked deeply in my work. Essentially, I use my artistic practice to reach an ontological balance that allows my work to transcend conventional time-space limitations. The overlap in time, in ritual states, allows for healing by way of memory.

In your album ‘In The Spirit Of Ntu,’ you explore the concept of “Ntu,” which holds profound significance in African philosophy. Could you delve deeper into the meaning of “Ntu” as a guiding principle in your music, and how does it manifest sonically throughout the album?

Ntu deals with essence, the idea that all things carry within themselves a kind of creative essence or vital force. Ntu is the language of all things. This means if we really have to understand the meaning of music, we have to deal with sounds within a much broader context of creation. Sounds, in this sense, become manifestations of Ntu.

Collaboration plays a significant role in your music, with your trio consisting of musicians from diverse cultural backgrounds. How does this diversity contribute to the creative process, and how do you navigate cultural exchange while maintaining authenticity in your sound?

The keyword here is collective memory. As a trio, we are constantly seeking to locate the “mother song” — this is a song of being that connects us to ‘uNomkhubulwane.’ For the most part, I bring in the thematic and compositional material, and the band responds from a place of intuition, informed by our different cultural musical libraries that are always related.

The album’s title track, ‘Omnyama,’ features hypnotic repeated figures and vocal incantations. What inspired this particular composition, and how does it reflect the overarching themes of the album?

This theme speaks to black origins. The song tries to invoke some kind of genealogy by reciting divinities through invocations as a way to launch into an invitation of spirit presence in this album.

You mentioned that the suite emerged from a “mother song” gifted to you during your initiation process as a healer. How did this experience shape your musical vision for the album, and how do you channel spiritual revelations into musical expression?

The “mother song” in this context is a song of in-tune-ness — this means “a willingness to be made anew.”

What are some of the most important players who influenced your own style, and what in particular did they employ in their playing that you liked?

I am currently inspired by cosmic rhythms and perhaps less by human music. But of course, I come from the music of my village and all improvised music that has inspired me. At this moment, I am not thinking about individual names but rather sheets of energies that inform a kind of library of everything I have heard in this life.

Have you found something new lately you would like to recommend to our readers?

I find myself moving more towards reading than listening to music, so I would definitely recommend Reaching Beyond: Improvisations on Jazz, Buddhism, and a Joyful Life (2016) by Daisaku Ikeda, Herbie Hancock, and Wayne Shorter.

Thank you. The last word is yours.

uNomkhubulwane

Klemen Breznikar

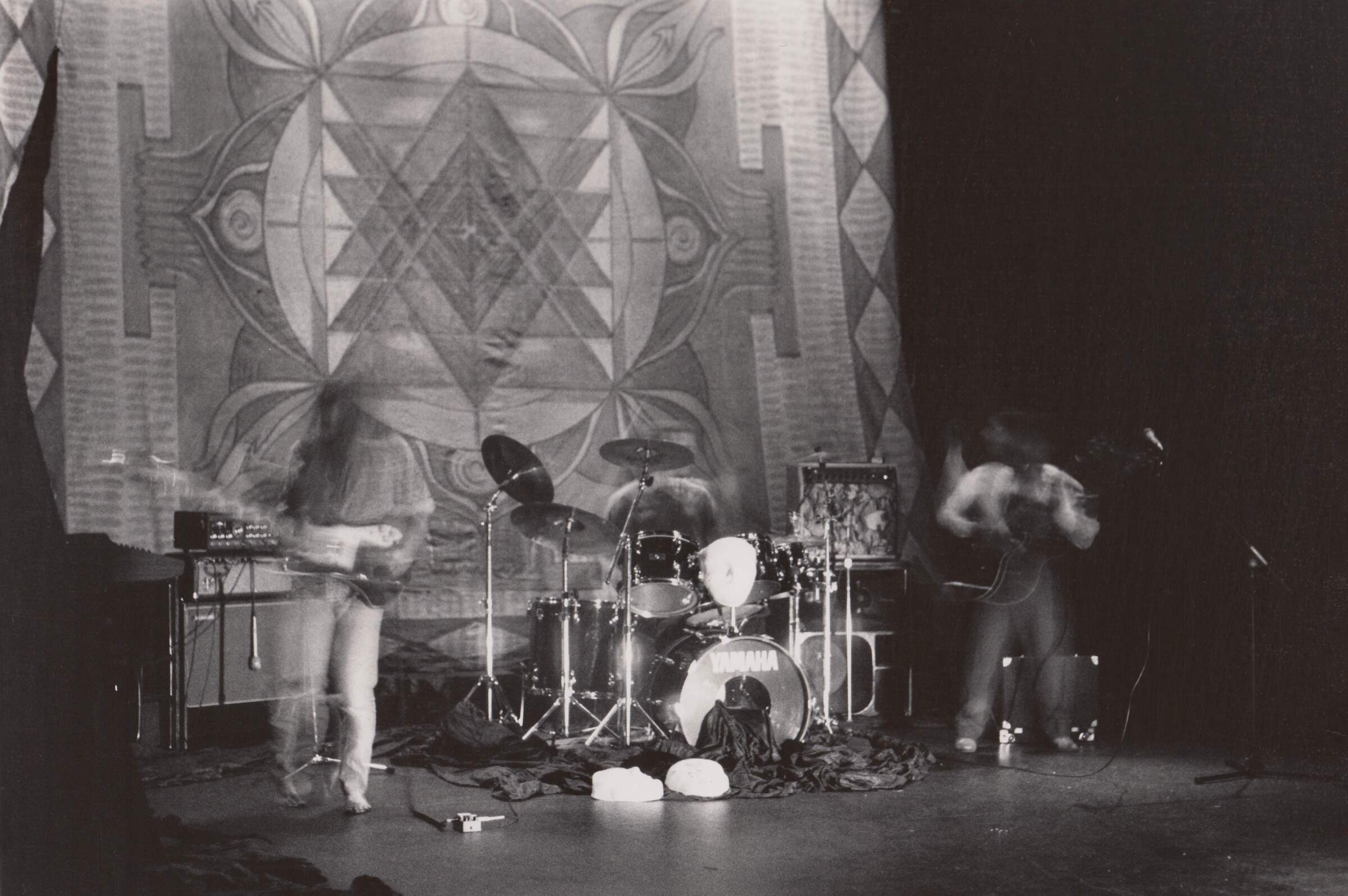

Headline photo: Arthur Dlamini

Nduduzo Makhathini Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube

Blue Note Records Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / YouTube