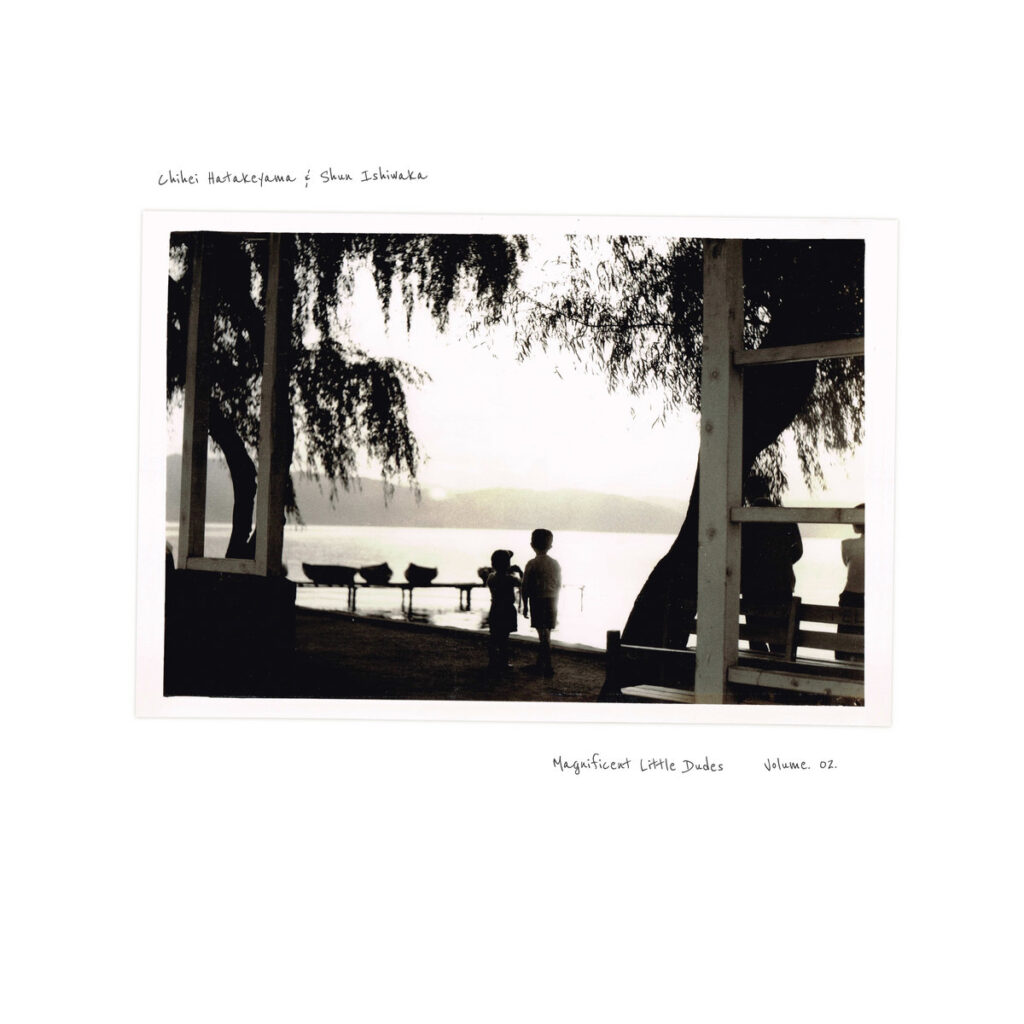

Chihei Hatakeyama | Interview | New Album ‘Magnificent Little Dudes’

Chihei Hatakeyama’s sonic journey is nothing short of a cosmic odyssey, where minimalism collides with expansive soundscapes.

From his early DIY days with ‘Minima Moralia,’ crafting intimate tracks with just a laptop, guitar, and vibraphone, to the richly textured layers of ‘Magnificent Little Dudes,’ his evolution is a testament to his restless creativity. Hatakeyama’s sound has morphed from digital experimentation to a lush array of analog and modular synths, capturing a freshness that feels both innovative and nostalgic. His approach to free and spiritual jazz isn’t about direct influence but rather a philosophical exploration of music’s deeper truths. His no-overdub, raw recording style on the upcoming ‘Magnificent Little Dudes Vol.2’ channels an indie spirit that eschews polish for authenticity. Collaborations with artists like Shun Ishiwaka and Hatis Noit bring a vibrant, eclectic mix to his work, blending personal connections with a broad sonic palette. Growing up by the ocean in Kanagawa, those serene coastal vibes still ripple through his music, grounding his experimental ventures in a deeply personal place. Balancing life as a mastering engineer, record label founder, and boundary-pushing artist, Hatakeyama’s music remains a thrilling exploration of sound and self.

Your musical career spans numerous albums and collaborations. How has your creative process evolved from your first album ‘Minima Moralia’ to ‘Magnificent Little Dudes Vol.1’?

Chihei Hatakayama: Back when I was creating ‘Minima Moralia,’ I had very little equipment, so I mostly recorded guitar and vibraphone onto my laptop and then processed it. I used many of the granular features of the software, such as Max/MSP or Reaktor. I had to sell my vibraphone afterwards as I couldn’t find room for it, which I regret doing.

Since around 2010, I started incorporating hardware synthesizers, and then, since the mid-2010s, I’ve also included modular synths, which is how the amount of equipment grew. 2010 was when guitar effects were really evolving, and I acquired many of them.

When you change the equipment, the sound changes, and I enjoyed the freshness of using each piece of equipment for the first time. I think that’s why I now have so many, but after a certain point, you hit a dead end. Now, I’ve shifted to using everything I have on a deeper level.

You’ve mentioned influences such as Alice Coltrane and Sun Ra. Can you elaborate on how these artists have shaped your approach to music, particularly in this latest project?

It’s not that I referenced anything in particular from Alice Coltrane and Sun Ra’s music, but it’s more about what came out naturally from me as a long-time listener of theirs. To use an analogy, it’s like a blend of coffee made from beans of various origins. Alice Coltrane, Sun Ra, Can, Keiji Haino, Les Rallizes Denudes, and everything else I’ve ever heard has passed through my filter and become a cup of coffee. I’ve never actually discussed Alice Coltrane or Sun Ra with Shun. After recording, I listened back and thought that somehow, it was influenced by their music. In fact, what Shun and I decided to do before recording was simply to be ourselves. We focused on how to play naturally in the way we wanted, by using the space differently. To use a soccer analogy, our ability to play our own game is determined by our power relationship with the other team. Even if our game is essentially about linking passes and playing aggressively, we will not be able to execute this concept if the other team is superior. However, in music, there is no enemy team preventing us from playing our own music. The only thing that prevents us from playing is ourselves. Therefore, I think it is important to always be aware of the outside environment so that we can direct our attention inwardly.

You’ve collaborated with many artists over the years. How did your collaboration with Shun Ishiwaka come about, and what was unique about working with him on this album?

I met Shun at a radio show he was hosting. We had our first session there. The recording was quite enjoyable and had a good feel. It had been about 10 years since I had a session with a drummer. It was also very refreshing because it was with Shun, an amazing drummer. Later, a festival organizer who heard our radio show invited us to an outdoor festival where we performed. Six months later, we recorded this album. There is no stress for me in a session with Shun. I don’t have to think about any details. One reason may be that he is from Hokkaido. My father is also from Hokkaido, so I felt they had something in common. I can’t really verbalize it, but is it the aura or atmosphere that the person has? I don’t know how to put it, but I don’t feel like I’ve met him for the first time. It happens sometimes, doesn’t it?

You chose a no-overdub recording style for this album, reminiscent of 70’s jazz recordings. What challenges and benefits did you encounter with this approach?

With the modern approach to recording, you focus on the details, redoing things over and over, correcting little mistakes, etc. I think that is fine for a certain kind of pop music. But for experimental music, jazz, ambient, and other non-mainstream genres, I think it is better to take a step back and look at things from a different perspective, not from that fine microscopic view of the world. So I didn’t even fix the mistakes.

The album was recorded over eighteen months. How did the extended recording period influence the final sound and feel of ‘Magnificent Little Dudes Vol.1’?

The recording of the album itself was done in one day. Only the two guest artists were recorded later in London. During that time, we discussed the editing with my label, Gearbox Records.

Can you discuss how the physical environment influenced the improvisational aspects of the album?

In fact, you could say that about 10% of the improvisational aspect of this album was influenced by the environment. I feel that 90% of the resulting finished music is already there. It is there but has not yet taken actual shape. I believe it is a natural result of Shun’s life and career as a drummer, as well as my own experiences to date. It is actually the most difficult thing to bring out what you have naturally, and sometimes you end up playing wrong due to some pressure. So I think it’s best if you can perform your own music and match it to the other person’s.

_photo-by-makot-1024x683.jpg)

What does it mean to you to be able to improvise when it comes to music making?

The process of writing your own songs and recreating them didn’t work for me. I think I was about 20 years old when I started playing improvised music, and at that time I was in a 4-piece band. I wish I still had the cassette tapes from those days, but my mom got rid of those at my parent’s house. After I quit that band, I didn’t engage in any improvised activities. Later, when I started using a laptop, I was able to improvise and edit my performances, and I mainly focused on editing. In a way, I think improvisation is equal to composition. It’s a question of how to record a phrase or a method once it comes to you. If you are sharing your performance with others, you will need sheet music or you can explain it verbally if you are physically there. If you’re making music by yourself, you could just record it once as data. So I think everyone is capable of improvisation.

-1024x382.jpeg)

‘M4’ features the ethereal vocals of Hatis Noit. How did her contribution shape the track, and why was she chosen as a collaborator for this piece?

I think it was about 10 years ago that I met Hatis. I’ve been wanting to collaborate with her ever since, if there was any opportunity to do so. I heard a female vocalist’s voice in my head when I was recording ‘M4,’ so I thought this song needed a female vocalist. My label, Gearbox Records, is based in London, and so is Hatis Noit. With that kind of connection, I thought it would be great if she could participate in this project, so I asked her to join.

You’ve stated that the album takes inspiration from free jazz and spiritual jazz. What philosophical or emotional dimensions of these genres did you aim to capture in this album?

In a philosophical sense, the record is not clearly inspired by free jazz or spiritual jazz. I cannot naively believe that there is some metaphysical truth behind music in this age of civilization and science, but I also know that there are many phenomena left in this universe that cannot be explained even by science. For example, I am strongly attracted to the idea of a multiverse. The last scene in the latest version of David Lynch’s Twin Peaks was also quite nonsensical, but from a multiverse point of view, it seems natural. The length of the music on this record is also long, and I made it so that you can talk to yourself while listening to it—not to say that it is a meditation.

How do you see the relationship between spontaneity in the recording process and the final structured form of the album?

I did not edit the songs with drums very much. Shun played the piano on some songs, so I edited those a little.

With ‘Magnificent Little Dudes Vol.2’ on the horizon, how does it build upon or diverge from the themes and sounds established in Vol.1?

They are Vol. 1 and Vol. 2, but they were actually recorded on the same day and mixed at the same time. We could have released them all in one boxed set, but after consulting with the label, we decided it would be better to release them in two separate sets.

The album is released via Gearbox Records, known for their focus on analogue recording. How does the analogue production process impact the final sound of your work?

In recent years, the difference between digital and analog mastering seems to be disappearing more and more, but you can still use analog gear, such as compressors and EQs, to create sounds that can only be achieved with analog gear. And the good thing about analog may be that it is inconvenient. In a digital environment, you can redo things as many times as you like, and I think the tension of not being able to redo things and not being able to undo things works in a very positive way.

As a mastering engineer and record label founder, how do you balance these roles with your creative pursuits, and how do they inform each other?

It is a very difficult task to shift your attention from mastering or working for a record label to focusing on your own creative work. I still struggle to find that balance every day. I think it’s the same for everyone, but there are also other aspects of life that come into play, so in reality, we just manage to do what’s in front of us every day. I would like to have more time to reflect on what happens each day and on my creative work, but I also have my life with family, and since I turned 40, time has gone by so quickly that I feel like I’m constantly rushing through it.

Your music often bridges traditional Japanese aesthetics with contemporary experimental sounds. How do you navigate and integrate these diverse cultural influences in your work?

I am not sure how well I understand traditional Japanese aesthetics. This is because Japanese people today have less and less contact with traditional Japanese aesthetics in their daily lives. I think, compared to people outside of Japan, I understand a little more of the traditional Japanese aesthetic… but from my point of view, I also want to first define what the traditional Japanese aesthetic is. This is because many of the things that are now considered Japanese traditions came from China and India in ancient times. For example, I think the tea ceremony is also influenced by Zen, but if you trace back to its origins, Zen is an Indian philosophy. So, for example, even if you think you have played drone music with a Japanese aesthetic, if you trace back to the source, you could find yourself in India, both musically and ideologically.

Looking back at your early life and influences in Kanagawa, Japan, how did your upbringing shape your musical inclinations and creative outlook?

I lived in Kanagawa until I was 27 years old. I once lived in Tokyo for two years when I was about 20, but I returned to Kanagawa and started living in Tokyo again at the age of 27. It was right around the time we released Minima Moralia. I was still working for a company at the time, so I moved to Tokyo for convenient commuting. The number of live performances was also increasing during that period, so it was better to move to Tokyo to be active in the city. I lived in Kanagawa and Fujisawa City, which is different from Tokyo as it is close to the beautiful ocean. So when I was in junior high and high school, I went to the beach whenever I had time. Sometimes I would fish, but sometimes I would just sit there. I feel that all those experiences in Kanagawa are feeding back into my current music. For example, when I am working on a song in the studio, I can see the seascape when it is a good recording. So it is a good performance when you are in a state of playing but forget that you are playing, and the old seascape is running through your mind. You can tell it is a bad performance when you are aware that you are playing and trying to make the song somehow good.

Let’s end this interview with some of your favourite albums. Have you found something new lately that you would like to recommend to our readers?

I would like to introduce some very good music, though it is not out yet. It’s the soundtrack to the movie 658km, Yoko no Tabi, composed by Jim O’Rourke. The music played in the film is unified with guitar playing, creating a very atmospheric and heartwarming sound. I don’t know how the soundtrack for 658km, Yoko no Tabi came to use guitars, but my guess is that it was influenced by Paris, Texas. But unlike Ry Cooder’s guitar, Jim O’Rourke’s guitar this time has a subtle nuance that smells of the Tohoku region of Japan. It’s a subtle nuance, but I really liked the slightly damp, cold feeling. The ending track of the movie is co-written with Eiko Ishibashi, and it is also very good. I felt like I was listening to Jim O’Rourke’s sequel to Eureka.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Makoto Ebi

Chihei Hatakeyama Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp

Gearbox Records Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube

_photo-by-makoto-ebi.jpg)