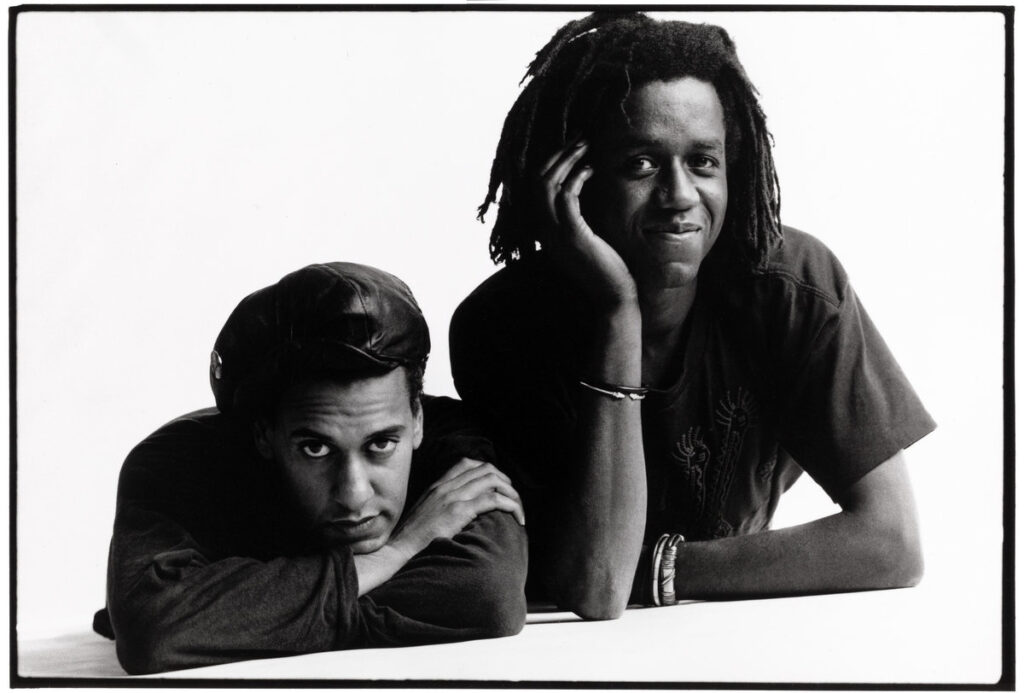

A.R. Kane | Interview | Rudy Tambala

A.R. Kane’s journey, from their groundbreaking debut ’69’ to the rebirth as Jübl, is like a wild ride through a sonic carnival—vivid, unrestrained, and impossibly ahead of its time.

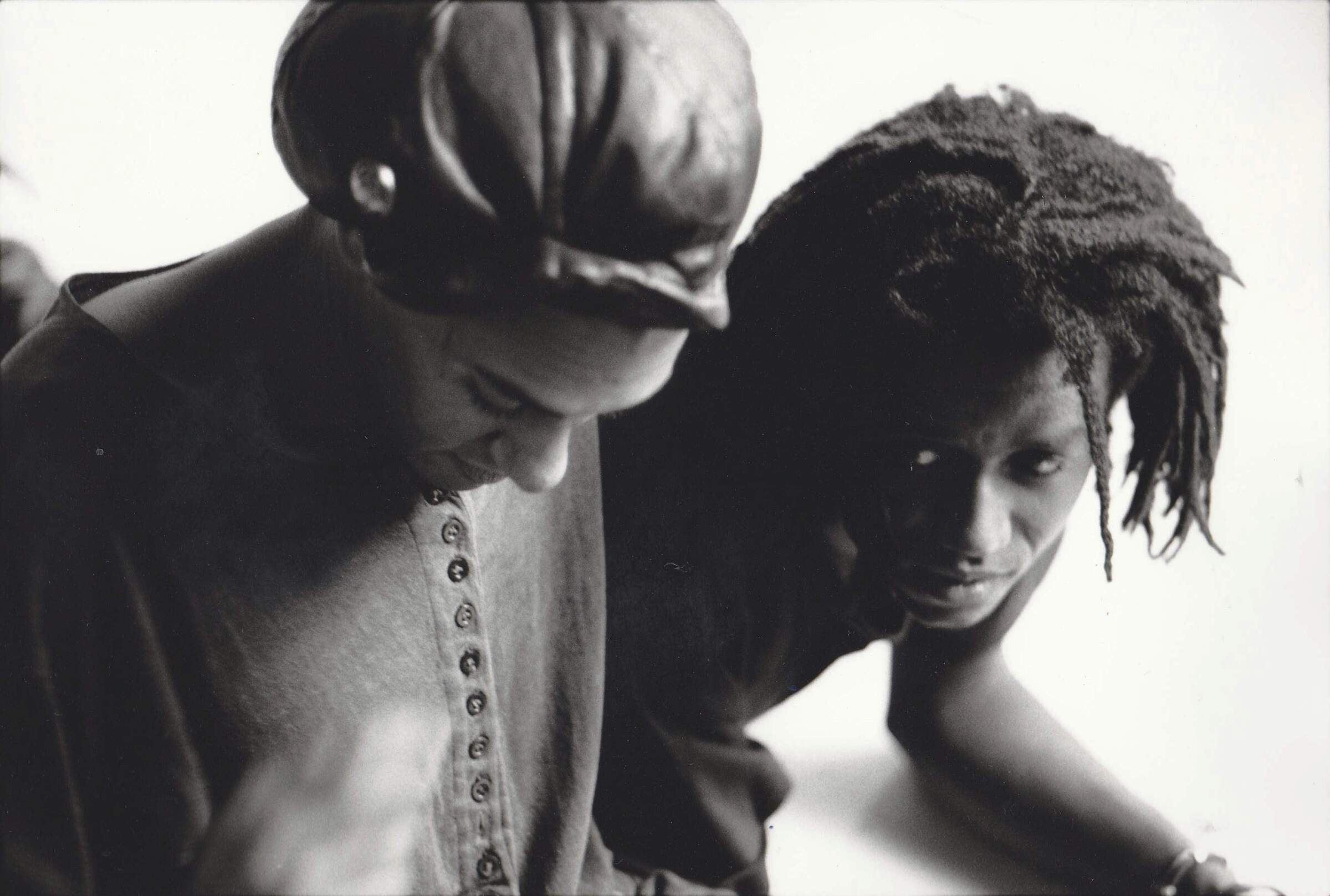

When they coined “dreampop,” it wasn’t just a nifty label; it was a defiant stand against the drab, cookie-cutter categories of the era. Their early work was a gloriously chaotic mix of influences, a frenzied dance of dub, psychedelia, and punk, recorded in the claustrophobic basement of Alex’s mum’s house like some alchemical experiment gone right. Fast-forward to Jübl and you’ve got a fresh chapter written with cutting-edge gear like the Ableton Push 3—proof that they’re not just keeping up but leading the charge into uncharted territory.

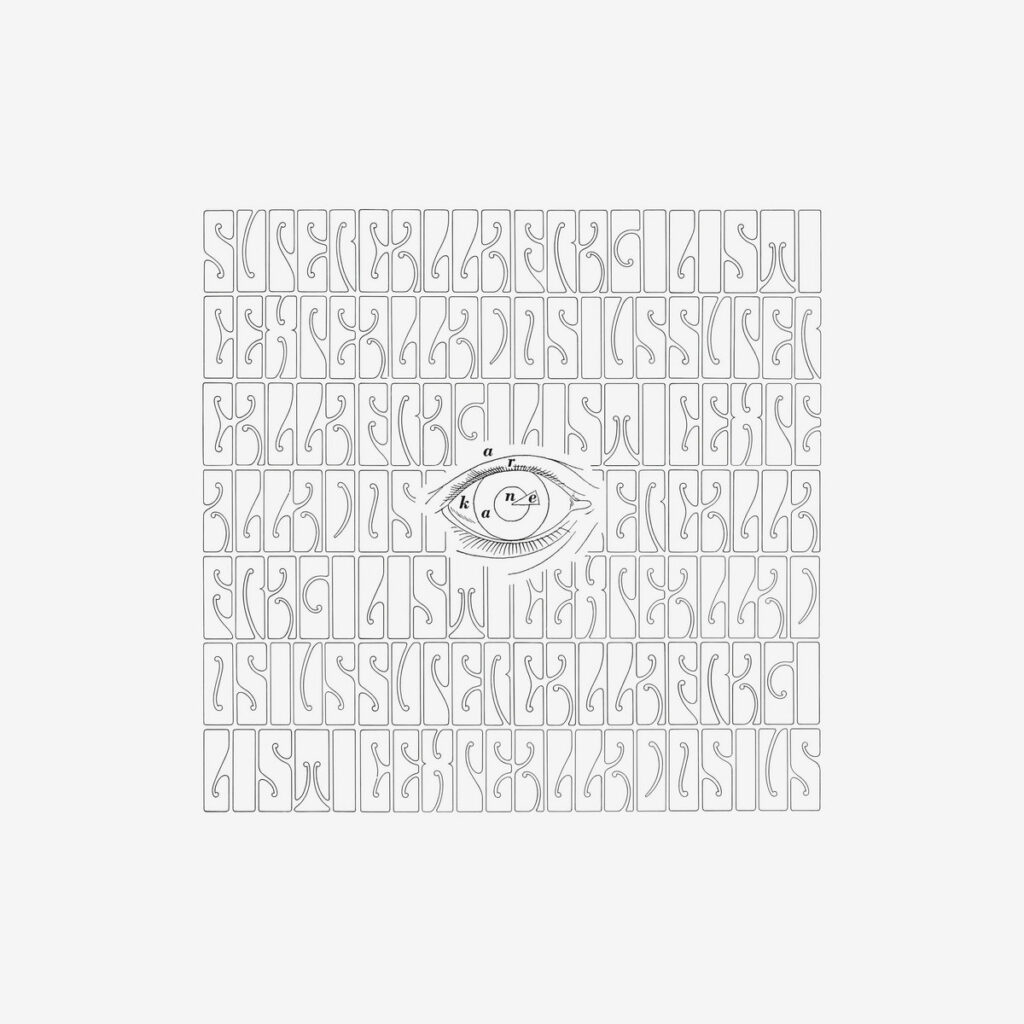

In 2023, A.R. Kane released a limited-edition vinyl box set, ‘A.R. Kive,’ featuring remastered versions of their 1988–89 LPs ’69,’ ‘i,’ and the ‘Up Home!’ EP, along with new remixes by artists like Slowdive. To celebrate, Tambala performed live at The Social and Cafe Oto in London with a lineup including Maggie Tambala and Budgie on clarinet, the latter credited on ‘The Sun Falls Into The Sea.’

“We didn’t know the boundaries, so we just kept going”

Your recent release, the limited-edition vinyl box set ‘A.R. Kive,’ features remastered versions of your early LPs and the ‘Up Home!’ EP, along with new remixes by artists like Slowdive. What motivated you to revisit these works, and how do you feel about the reinterpretations by contemporary artists?

Rudy Tambala: There were a number of factors that influenced me. One was a feeling that we had never really told our own story. Another was that I have three children, and I wanted them to know what we achieved. The third, the catalyst, was when I was moving home, and I uncovered the collection of old vinyl, tapes, and so on. I decided to catalog it all, to make an archive, and then it hit me: “Pull this all together and release it!” I then had to overcome a major obstacle; One Little Indian Records claimed that historically they owned the rights to my catalog—we argued this for a few years, but they never showed any documented evidence—the fact is it never existed. So I told them my intentions, found a label—Rocket Girl—and started the labor of love. OLI whinged loudly but then fell silent—their bluff failed. I will never understand people like that.

With Rocket Girl, I had the opportunity to restore the tapes and remaster everything to make it sound better and to then lovingly package it, add merch, etc. It was an amazing experience—part nostalgia, but mostly very now, very present.

Having remixes done was such a gift too—Slowdive did an insane version of “WOGS.” My son Louis, aka TAMBALA, is a UK producer (hip hop, drill, lofi, etc.), and he did a beautiful remix. Tim Reaper did a jungle remix too—it blew me away. I would like to have a hundred reinterpretations… our songs lend themselves to that… maybe one day.

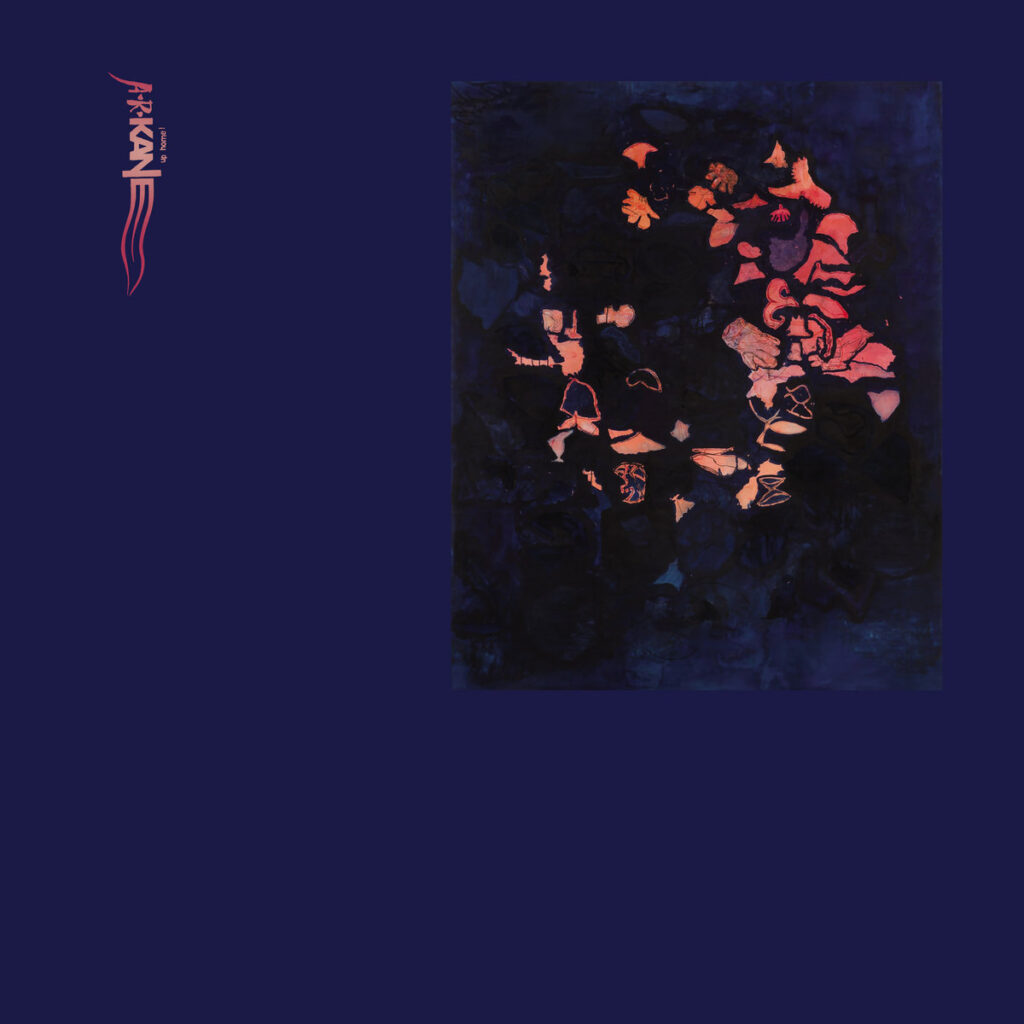

The ‘Up Home’ EP has been described as a pinnacle of an era filled with astounding landmarks of guitar reinvention, showcasing A.R. Kane at their most elixir-like. Could you delve into the creative process behind this EP and how it represented a culmination of your artistic vision at that time? Furthermore, how do you reflect on the lasting impact of the EP, particularly in the context of subsequent shoegaze bands, and what do you believe sets it apart from other works of the genre?

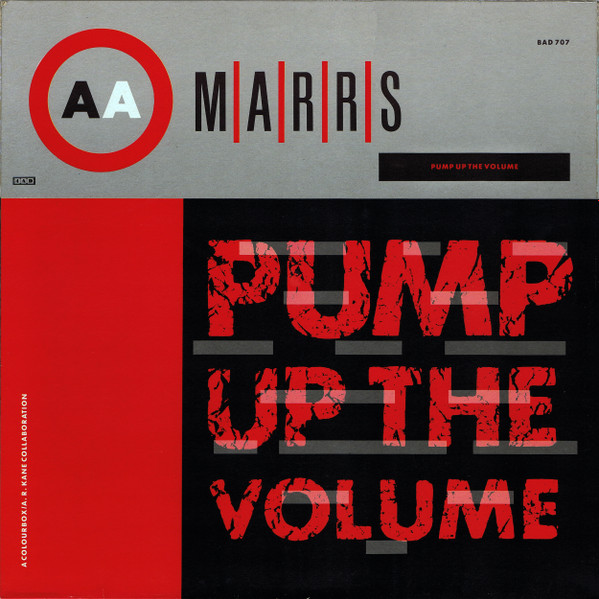

It was a synthesis of many different musical influences that happened at a time when we were very creative and also buoyed by the success of our 4AD releases (M|A|R|R|S ‘Pump Up the Volume’ & ‘Anitina,’ and the ‘Lolita’ EP). We were very confident and were welcomed and given a lot of encouragement by people like the Cocteau Twins, Ray Shulman of Gentle Giant (our mentor), Dead Can Dance, and others on the alternative London music scene.

Alex and I, being children of immigrants in the melting pot that was ’80s London, absorbed many influences—some mainstream popular culture, some foreign, some alternative—and put our spin on them.

Key influences on the EP: dub music, which gave us the dreamlike space; ’60s psychedelia, which helped us reach into another kind of consciousness and mindset; punk, which provided a DIY ethic and aggression; jazz and free jazz, which informed the sonic and harmonic deconstruction; baroque classical, for that timeless sense of beauty, refinement, and grandeur; soul music, for the immediacy of the voice; and technology—sampling and sequencing were in their infancy then, and everything felt new.

We were lucky to have worked with Robin and Ray, who taught us how a studio works, how effects can be used, and what instruments are capable of. Russell Smith, our bassist at the time, also brought in something that helped us hook into the alternative scene—he had a huge record collection and was massively into Sonic Youth, Butthole Surfers, Swans, Spacemen 3, Syd Barrett… We would hang out with Russell, do hot knives, drop acid, and listen to all this amazing post-punk and psychedelia. It had a huge impact on our style. Russell kinda taught us the musical vocabulary of the contemporary alternative music scene, from which we springboarded into our own space, taking our other influences with us.

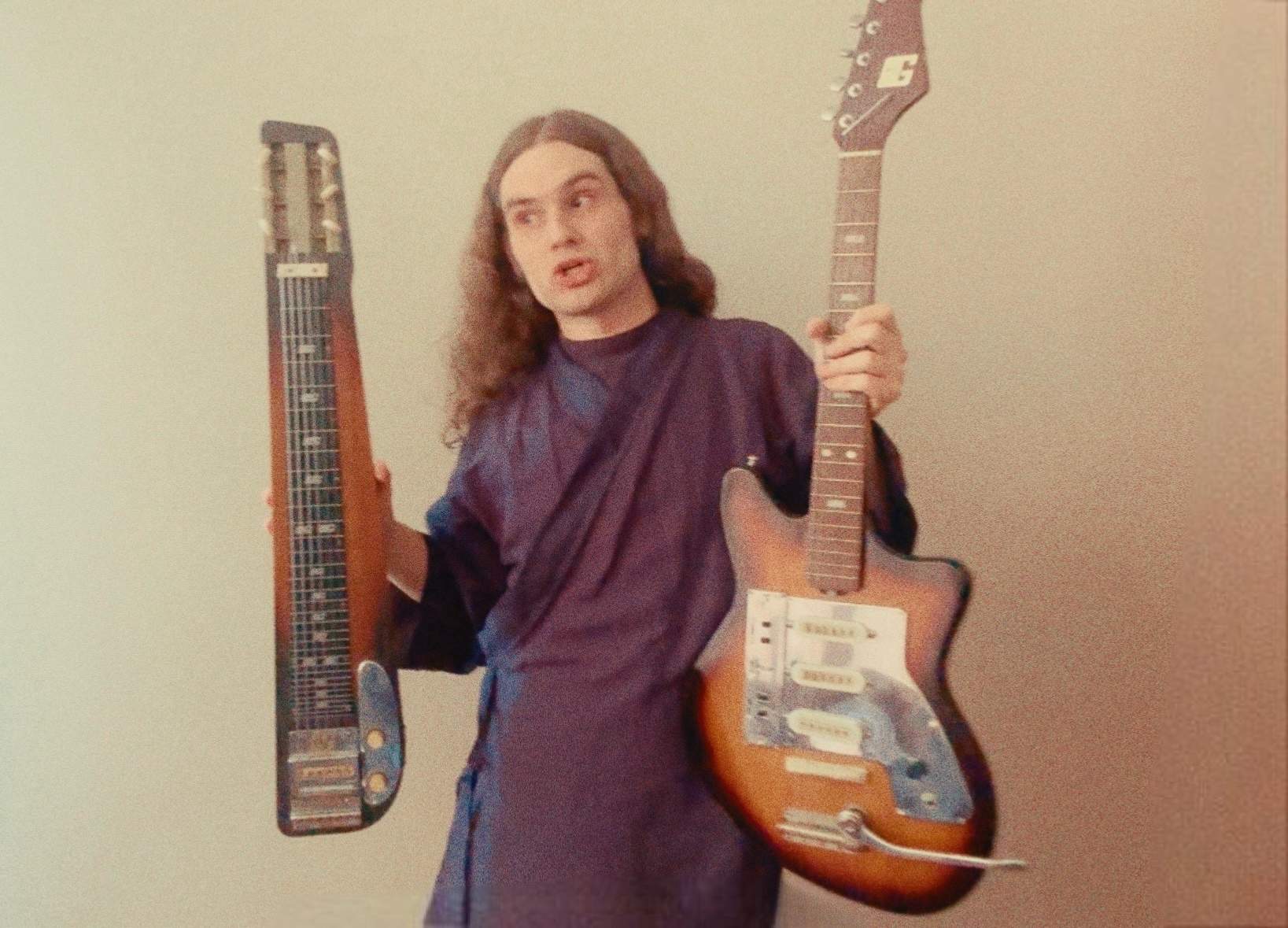

I have been told that the EP was very influential. My take is that we introduced new musical influences into the alt scene—the dub spaces, the effects-drenched guitars, the out-of-body vocals. On ‘BMS,’ I used echo, delay, reverb, and distortion on my guitar, which I played flat on my lap with a bottleneck, sort of accidentally inventing the ‘glide’ sound that became so popular. We also layered the guitars. Our aim was to make the guitars sound like anything but a guitar.

Up was maybe the dreampop/shoegaze pinnacle for us—we went all out, threw in everything we had, including the kitchen sink, dishwasher, and blender. That sonic excess and rapture could have been a failure, but it worked. It is transcendent, and its influence—direct or indirect—is still heard today in every shoegaze song performed. No apology; this sounds arrogant, but it’s simply a fact.

What sets it apart? Well, I think our approach. We were not trying to create rock music, and we were not experimental either. We were playful. Amazed. Hypnotized. We didn’t know the boundaries, so we just kept going. We found ourselves in uncharted territory, and we liked it there. Children of immigrants. Strangers in a strange land. We had a freedom. For a millisecond, we were free. Free from and free to.

Could you delve into the creative process behind crafting such a diverse and expansive collection of tracks on ‘i?’ How did you maintain cohesion while exploring such varied sonic territories?

We used the term dreampop to describe our music. We were deeply into dream mythologies, lucid dreaming, the dreamlike state of LSD, and the music and imagery that can be found within dreams. We would harvest our dreams, in a sense, and then try to recreate the melodies and rhythms, the emotions, the distortions and refractions, the dream logic… and at our disposal, we had an array of tools: the musical instruments—guitars, effects, drum machines, other musicians, synths, samplers, sequencers, the studio itself.

As we became more proficient in all these areas, we were able to explore more genres—dance, classical, reggae, rock, experimental, jazz, pop, etc. So we’d have an idea, find the right musical setting, and just go for it. No rules but our own enjoyment gauge and aesthetic sensibilities. Pretty bloody self-indulgent.

When we had finished recording all the song snippets, we had the insane task of pulling it all together into a cohesive whole. Luckily, a pattern started to emerge; we were reading Gurdjieff at the time, and he stated that the human being had four centers—Intellectual/Emotional/Moving/Instinctive. We saw that this framework neatly fit the diverse mix of tracks we had, so it helped us to organize and categorize the songs into these groupings. They are represented on the LP as the suits in playing cards, across four/five sides of vinyl. I’ll let you figure out which is which.

‘i’ has been hailed as a prophetic work, foreshadowing major musical developments of the 1990s. From techno to dub to shoegaze, the album seems to traverse a wide spectrum of genres and styles. How intentional was this foresight, and did you anticipate the album’s lasting influence on subsequent musical movements?

I don’t think we had any foresight. One thing was that we didn’t want to sound or be like anyone else. This was true of both Alex and me as individuals and more so as A.R. Kane. Politicians and corporations seek to have influence. I’m not sure musicians do. We didn’t. We were very much living in the moment, albeit with a sense of hyparxis.

Following the release of ‘i,’ your output became more sporadic, eventually leading to the dissolution of A.R. Kane. How did the dynamic between you two evolve during this period of transition?

Evolve is not the word I’d use. Devolve is better. Alex moved to California, and I stayed in London. The relationship we had loosened, and eventually the communication and the chemistry were gone. The “magic” we shared dissipated. Like a relationship, it was over. It’s amazing; it happens almost universally in bands, but no one ever sees it coming. Just one day, it’s gone.

In tangible terms, we stopped writing together and started writing alone and asking the other to “lay down some guitar” or whatever. We became a fucking rock band! There were some special moments on New Clear Child, but there was little enjoyment and no playfulness. By the time we came to demoing LP 4, we both knew it was over. I do miss working with Alex; we bounced off each other in a way I’ve not experienced with anyone else—never that telepathy or intensity.

Your debut album ’69’ received critical acclaim and topped the independent charts. How would you compare it to your later output?

It’s titled sixty nine. It is not like any of our other output. One thing is the production approach. We took our recording advance, built a 16-track studio with the bare minimum of outboard gear, a sampler and sequencer, some tape echoes, and various guitar effects. We immersed ourselves in the studio day and night—it was in Alex’s mum’s basement of her house in Stratford, East London. We learned to use all the gear by writing and recording songs. We didn’t know what we were doing, but we knew why we were doing it. It was immediate, fast, lo-fi, and joyful. It was dark. We would write the song, record, and mix it the same day. Check and adjust the next morning. Move on to the next one. Impossible to repeat the approach, mood, situation. Wouldn’t want to.

When it came to mastering, we went to Abbey Road—or was it Town House?—with our mixes. We were terrified; we thought the engineer would say, “Sorry, this is shit.” He played the tapes, looked up, and said, “Yeah, sounds pretty good, not much to do here.” Phew!

The key thing we did was try to make it flow like some of the LPs we thought were awesome—’DSOTM,’ ‘What’s Going On,’ ‘Supper’s Ready,’ ‘A Love Supreme,’ ‘Brandenburg Concertos’—the way that songs blended one into the other or had movements and fugues. Ray told us we needed a good engineer in a studio with three tape machines to do “cross fades.” We had to have that; we wanted side two to be a mini trip, no spaces, continuous listening. Immersive. That was quite different for an indie band, kinda conceptual. Prog, I guess. Hahah, we reclaimed prog for the post-punk generation—whoop!

The term “dreampop” is often associated with your music. Could you elaborate on how you came up with this term and how you feel it encapsulates your musical style?

Already answered that above, except to say we created it because we never felt aligned with any of the categories that existed, which in truth only existed to serve the categorization needs of the record stores and radio shows of the time. Fuck those categories, we’ll invent our own. Dream Pop. We mentioned it in an interview, the journos liked it, and boom, it took off. Now it’s a genre all its own, that bears some similarities to what we did, in songs like Lolita, Up, Green Hazed Daze, Sperm Whale Trip Over, and so on. The dreamy tracks with the blurred edges and melodic style. For us, it was all dreampop—the dub, the noise, the dance, the punk. Not just the pretty songs. Later we got described as progenitors of shoegaze, but seriously, your honor, it was not our fault. We never gazed at shoes.

In 2018, the revived band renamed itself Jübl. What inspired this “forward-thinking rebrand,” and how does Jübl’s musical direction differ from A.R. Kane?

I reformed the band in 2015 for live work. Alex didn’t want to join, so I did it with Maggie—our original backing singer and my lil sis—and Andy, a friend. We played for a couple of years and quite naturally started writing new songs that merged with the A.R. Kane originals in the live sets. When we had enough compositions for an LP, I told Alex I had made a new LP as I was intending to release it as A.R. Kane and that I wanted his blessing. He said he’d prefer it if I used a different name, that A.R. Kane was him and me.

I only partly agreed with him but didn’t want any hassle. So I changed the name.

The name Jübl is adapted from a character, Jubal, in Stranger in a Strange Land, one of my favorite novels. Fun fact: I found out later that Jubal—Old Testament—is considered the inventor of music. Musically, Jübl songs could have fit on A.R. Kane records and vice versa. Technologically, Jübl is more advanced. Creatively, I think it is on par but is not as radical because so much time has passed and so much of what we did is in the standard canon of popular music now.

Your collaborations have been diverse, including the one-off project M/A/R/R/S, which produced the dance hit ‘Pump Up the Volume.’ How did these collaborative experiences influence your approach to music-making within A.R. Kane?

From day one, we were always open to working with anyone that walked through the door. Everything was good, everything had meaning, anything was possible. Initially, it was Ray, then later several of the 4AD stable, then the East London music scene around Stratford, the people from all over. It is such a joy working, playing, teaching, and learning from others. Collaboration was central.

The reformation of A.R. Kane in 2015, followed by the spinoff as Jübl, seems to mark a new chapter in your musical journey. How do you envision the evolution of your sound and artistic expression?

I have a new live lineup—Maggie on lead vocals, Budgie on clarinet (he played on sixty nine), and Filipe on guitar. My live gear setup became too complicated with all the guitar stuff, the dub echoes, and the laptop, control surface, etc., so I bought an Ableton Push 3 standalone to make it simpler. This was a radical move and unexpectedly has changed my whole approach to performance and writing—it is a new generation of musical instrument—very expressive, quirky, amazing sound. I am setting up a production suite this summer, and it will feature at the center—I expect the juices to flow and the songs to come. I don’t know yet what name I will record under. Sole Kane?

Looking back on your career from its inception to the present, what are the most significant lessons you’ve learned?

I need meaning in my life. At different times, it comes from different sources. Music is one of those sources. It is endless. It never wears out.

The music “business” is a shark-infested sea—swim only when necessary.

Humans do two things really well:

Destruction.

Creation.

Let’s end this interview with some of your favorite albums. Have you found something new lately that you would like to recommend to our readers?

The last LP I heard that I felt really pushed the boundaries was ‘Blonde’ by Frank Ocean.

The LP I’ve listened to the most that I never tire of is ‘Astral Weeks.’

I like too many LPs to list them all here—here is a sampler of songs I like:

Thank you for taking your time. The last word is yours.

Thank you so much for giving me the time and space to rattle on like this. I like talking about music almost as much as listening to it, but nowhere near as much as making it. Advice—to all humans—buy a record deck and 10 records with your next paycheck. If you don’t have a job, steal the money or sell something, then buy a record deck and 10 records. Choose well.

Klemen Breznikar

A.R. Kane Facebook / Instagram / Bandcamp

Rocket Girl Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / YouTube