Greg Sneddon | Interview | Souls of Ambience

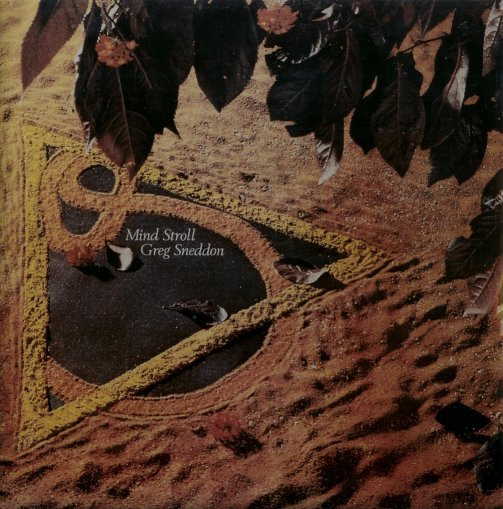

Greg Sneddon, an Australian composer and instrumentalist, embarked on his musical journey with the ethereal LP ‘Mind Stroll,’ released in 1974 under Mushroom Records.

During his journey, he also played a pivotal role in the early lineup of Men at Work, contributing to their initial recordings. A maestro on the keys, he currently guides his sonic visions with Kevin Kershaw, Marek Taborsky, and Chris George to conjure the evocative soundscapes of Souls of Ambience. Their debut album, ‘A 1000 Tears,’ is a haunting tapestry of gothic, progressive, and psychedelic rock, weaving lyrical narratives that transcend the mundane and venture into the surreal. Sneddon’s compositions are a delicate dance between the subconscious and the ethereal, each note a step in a poetic journey through darkness and light.

“There is no right or wrong. It just is”

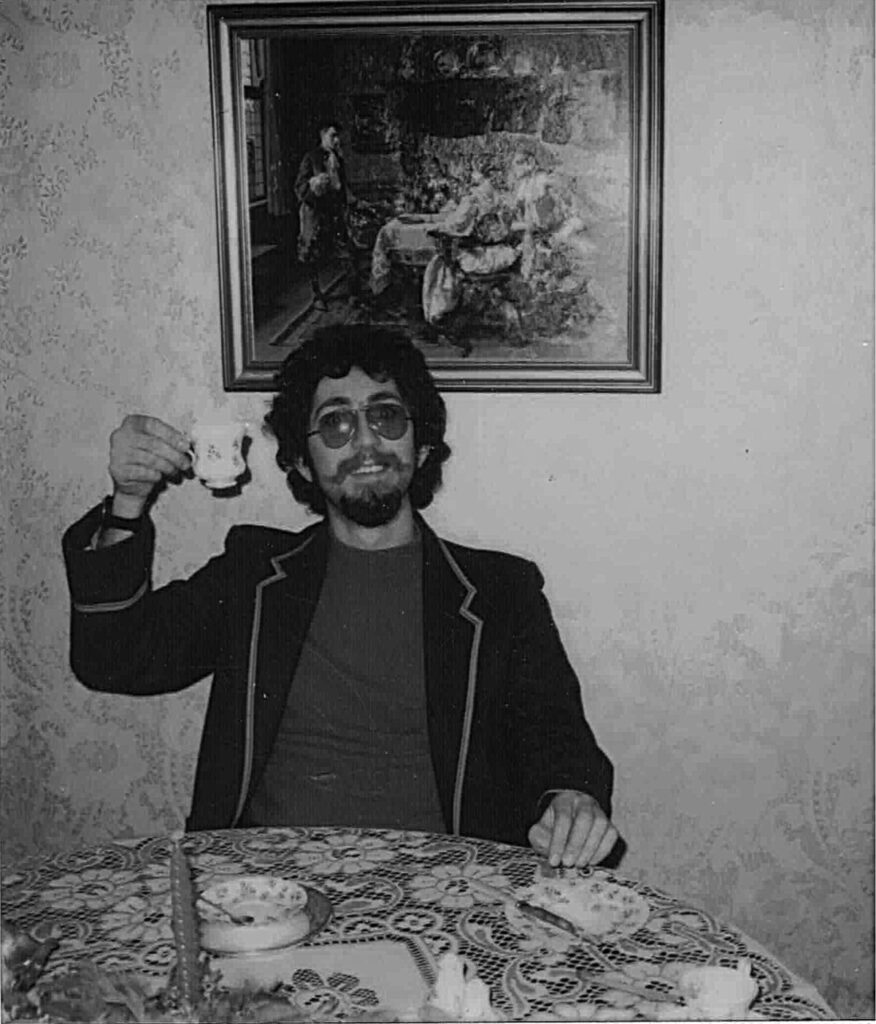

Where and when did you grow up? Was music a big part of your family life? Did the local music scene influence you or inspire you to play music?

Greg Sneddon: My parents were both into classical music. Going to classical music concerts and listening to records are some of my earliest memories. Mum decided before I was born that I was to be a pianist, so at the earliest opportunity, at five years old, I was learning the piano from some famous cranky old master who was the student of some other even more famous cranky old master.

The discipline of piano practice was not a good fit for my wild-child nature. I was always in trouble with my teacher for not practicing enough. He had a wooden ruler and would hit my knuckles with it when I made a mistake. Despite that, if I could get away with it, I would not practice at all.

When did you begin playing music? Who were your major influences?

I remember the first time I was given a simple J.S. Bach prelude and fugue to play. I’d never heard Bach before and it just blew me away. At nine, I was enlisted into the Australian Boys Choir. Always in trouble – a major theme of my life really – some of the songs we sang were beautiful. One day, I walked past a choir rehearsal room and there was the musical director with the senior choristers listening to a record. I froze. Some past-life thing or other, not sure. My life changed. It was Tallis’s 40-part motet ‘Spem in Alium.’ If you haven’t heard it, Klemen, make sure you do before you die. It really is one of the most remarkable and beautiful pieces of music ever written. An insane composition. Totally psychedelic.

At age 13, I realized the imposed construct “Greg the classical pianist” was only in place because I allowed it. Thinking the entire universe would implode, I told my parents I wanted to stop learning piano. To my surprise, they were in agreement. Shortly afterwards, Dad bought me an AceTone organ, similar in sound to the Vox Continental played by the Doors’ Ray Manzarek.

At around 14, I joined my first band. They were a few years older than me and were OK, but had never played with a keyboard player. The first rehearsal was a disaster. Lead and bass guitars were in tune with each other but nearly a semitone flat relative to the AceTone. So they are playing pop songs in E and A while I’m playing in Eb and Ab. I remember not understanding why anyone would write songs in such obscure keys.

In the same year, Iron Butterfly released their song ‘In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida.’ I was captivated and studiously practiced the keyboard line. It is one of the best early psychedelic songs.

What kind of records and singles would we find in your teenage room?

Black Sabbath’s ‘Black Sabbath’, the Beatles ‘Sgt. Peppers’ and ‘Abbey Road’, the Stones ‘Their Satanic Majesty’s Requests’. Later, King Crimson’s ‘In The Court of the Crimson King’, ‘Yes’ by Yes, Floyd’s ‘A Saucerful of Secrets’ and ‘Ummagumma’. The Moody Blues ‘Nights in White Satin’.

As I was writing songs as a teenager, then as now, I didn’t tend to listen much to other people’s music. Satisfying the internal creative was paramount. “Out there” was merely a stimulus to “in here.”

Was there a certain moment in your life when you knew that you wanted to become a musician for the rest of your life?

I have no memory of a time before I was actively engaged in the study and practice of music. The possibility of creating music for a living came from a growing momentum caused by positive feedback from others. The first serious music I wrote and recorded was at home on a B&O two-track with bounce down, meaning I could build layers. It was totally psychedelic/prog in style. Endless washy moods, trippy lyrics, that kind of thing.

Were you in any other bands before you joined the Alroy Band? Any recordings?

Alroy Band was the first really good band I played with. The guys and their families became my family. We toured around and had loads of fun. However, we were not playing my songs, rather playing a style that would have been called at the time “Melbourne Rock.”

Before and during Alroy, I was living in “The Manse,” a loose-knit commune in an old house in Carlton with a wild bunch of musicians. Rob McKenzie and Cleis Pearce from Jazz Fusion band McKenzie Theory rented one room, exotic Joplinesque singer/dancer Claire and dancer/choreographer Benny Zable were elsewhere. Creative hippies and strange people came and went. It was quite a time. Out of this creative cauldron, a band For Madmen Only was formed with drummer Sponge from Sydney. The band’s name came from a scene in Hermann Hesse’s novel Steppenwolf. For Madmen Only played only a few times, but they were memorable events. There was a popular venue called Alberts’ or ‘Berties. It was an amazing old castle-like five-story mansion in the Melbourne CBD. No lifts, only stairs. One band in the basement and another band in a little theatre in the attic. We played the attic one night. Sponge had a nine-foot carpet snake he would bring on stage and we put on a theatrical show with dry ice, fire eating, epic music, makeup, and costumes, that kind of thing. It was really good stuff. That night was a packed house, maybe 150 people shoulder to shoulder. During a Doors-like trance music sequence called ‘Clear Light’, someone ran on stage and said the snake had escaped, which caused quite a stir in the audience. The music continued while the lights went to near-black in the fog. Then Claire lit a distress flare which was supposed to be dropped in a bucket of water just off stage. However, she couldn’t see a thing and missed the bucket, causing the red velvet curtains to catch alight. Most people in the audience were stoned and were saying, “Wow, what a show, that is so cool!” We kept playing while the bucket of water was used to douse the curtains. The room was now full of smoke, so coughing and spluttering, the audience made their way out down the steep staircases. We kept playing, colored lights shimmering through the dry-ice fog. I thought, “this is it, the venue owners are going to kill us.” But those were the days – the promoters loved it and wanted us back.

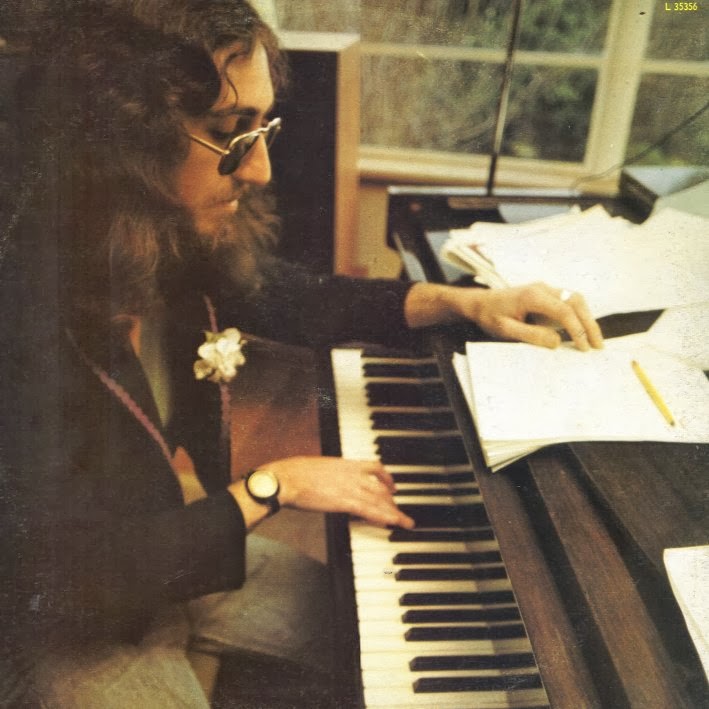

In 1974, you released your solo album ‘Mind Stroll’. Where was the album recorded and what was the original concept behind it?

While playing with Alroy Band, I was writing psychedelic/prog music and recording it at home. A local studio with a 4-track helped turn the songs ‘Mind Stroll’ and ‘A Spell of Destruction’ into a demo, which was presented to Michael Gudinski’s Mushroom Records with the idea of doing a solo album. ‘Tubular Bells’ was playing regularly on the radio and Michael thought that, as I had a distinct synthesizer sound happening, maybe it would work. I’d been jamming with Jerry Speiser (Men At Work drummer), Phil Butson (guitar), and Gary Rickets (bass), and when Michael asked if I wanted to use any session musicians on the album, I thought they would be great. Looking for someone to share the quite complicated singing, Dayle Alison joined the band, which was called Lyon.

We recorded ‘Mind Stroll’ in Sydney at producer Charles Fisher’s studio. The multi-layering work I had always planned to do after the beds were recorded took up a lot of studio time to the point that the title track ‘Never Drops’ was never finished, and the album as a result is quite short and had a name change.

Conceptually, I was looking to present theatrical dream images from a self-analysing mind that had become just a little unstuck.

Tell us about the gear you used.

Acoustic grand piano, Hammond B3, ARP Pro synthesizer, Mellotron, Hohner Clavinet, Spinnet, Fender Rhodes.

The first mix presented to Mushroom was deemed too straight, so producer Charles, engineer John Sayers, and I were tasked with remixing to make it more psychedelic. So, lots of phaser, flanger, and tape echo effects later, the release mix was complete.

As a session musician, you played on Skyhooks albums ‘Living In The 70’s’ and ‘Ego Is Not A Dirty Word’.

Somewhere during the time when Lyon was touring the ‘Mind Stroll’ album, Mike Gudinski asked if I would play synthesizer on Skyhooks’ ‘Living In The 70’s’ album. More correctly, make synthesizer noises that could articulate points in the songs. I didn’t know their songs and there were no chord charts, but that didn’t seem to matter. Producer Ross Wilson knew what he wanted, and so the buzzy alienesque sounds were recorded, giving quite a recognizable character to the recordings.

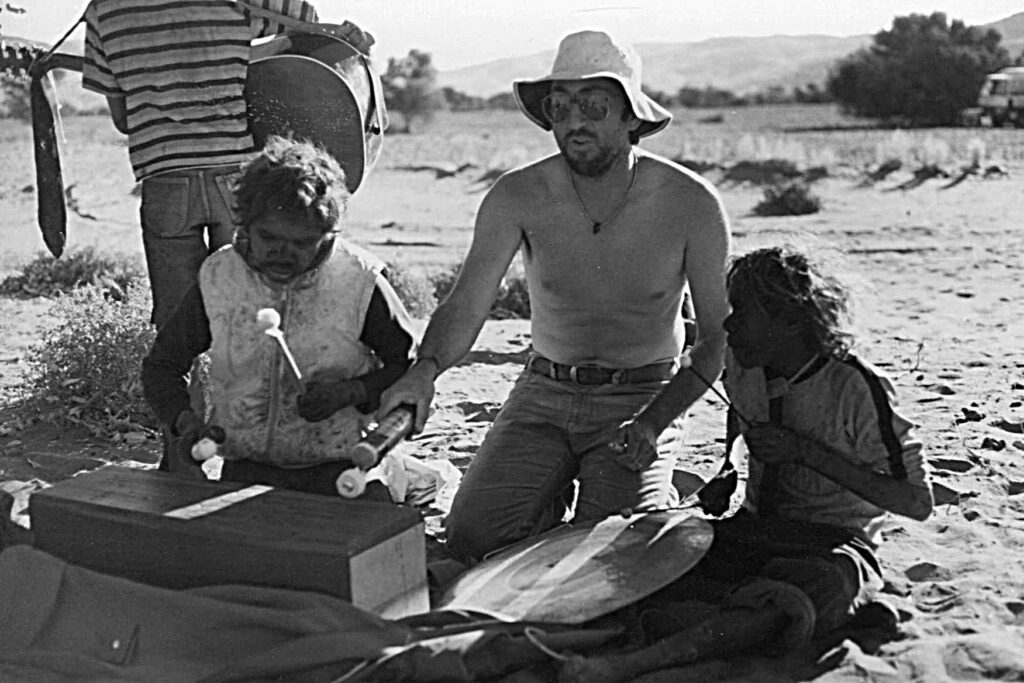

You were also commissioned to write scores for award-winning films, television (e.g., The Theme To The ABC TV Series The Explorers), commercials, and events. Tell us more about this period of your life.

Soon after ‘Mind Stroll’ was released, I received a call from the Australian Broadcasting Commission’s wildlife film production unit, asking if I’d like to write and record the score for a documentary series on a little-known island near the Antarctic called Macquarie Island, to be called ‘Edge of the Cold.’ David Parer’s cinematography was exquisite, and I enjoyed writing and recording the music immensely. Soon after arrived another commission, then another. From documentary scores to drama scores, then mini-series scores. It was a fortunate time, and I was fully occupied as a film composer for over twenty years.

A different stream of work began with an invitation from West Theatre to join the company as Composer in Residence. This was different, as it involved writing songs to fit into the many original plays they wrote and produced. One major project we worked on was called “Riff Raff,” a musical written and performed by the company for schools.

The musical needed a band to perform the songs on stage, and I asked Jerry, Phil, and Gary from Lyon if they would be involved. We needed a strong singer, and Jerry said he had met this guy Colin Hay who had a solo act called Colin Hay and the Shrubs. We went and listened to Colin and to be sure, he had a voice. The Riff Raff band was formed.

Gary and Phil dropped out, and the lineup became Colin on lead guitar and vocals, Ron Strykert on bass, Jerry on drums, and myself on keys. It has been referred to as the original “Men At Work” lineup. Colin singing ‘The Ways of the Broken Hearted’ was a high point of the show.

Following Riff Raff, Men at Work began developing Colin’s songs. Meanwhile, I was writing film scores and traveled to Europe and the USA a few times. One time when I was in Melbourne, Jerry phoned and invited me to The Cricketers Arms hotel where Men At Work were rocking a full house. They were great. For years whenever Jerry was in town and I needed a session drummer, he was it.

Somehow I ended up giving a lecture on music for theatre at the Victorian College of the Arts drama school. Three of the students had been invited to run a drama class in Fairlea Women’s Prison. They asked if I would come along and work with them. Thus was born the Fairlea Drama Group, later called Somebody’s Daughter Theatre. Over the years, I wrote many songs based on the stories of the lives of the women both inside prison and after their release. The lyric content of the current batch of Souls of Ambience songs draws heavily from the life experiences of the people I met during that period, many of whom have died since from drug overdose or domestic violence-related manslaughter. It is important for me to tell these stories and is one of the conceptual foundations of the Souls of Ambience album ‘A 1000 Tears’.

What led to the formation of Souls of Ambience?

After writing and directing the cinema feature film Arrows of the Thunder Dragon, I was looking for another creative project. Bored with my own tame recordings of songs I’d written, I wanted to do something with more grunt. I found Kevin on Bandmix. His background is NWOBHM of which I am not a huge fan. He spoke of some band called Iron Maiden; I politely asked Iron who? I waxed lyrical about Black Sabbath, Slayer, Patti Smith, and Velvet Underground. He shook his head and said, “Yes, but they are not really metal.” He had a huge old-school Rickenbacker sound; I was fussing around trying to get him to appreciate the nuances of F#sus4/C# and so forth. Anyhow, it was a match made by the gods.

Chris George came highly recommended, having been thumping kit for the serious metal band Chariot Arcana, yet also sporting a lightness of touch reminiscent of Nick Mason.

Then Kevin found guitarist Marek Taborsky, lurking around whatever dark places metal tribute bands members hide between gigs. Given Marek had only been playing the near-impossible leads in Metallica, Iron Maiden, and Slayer tributes without working up a sweat, I think he thought we were a bit light on in the power department to start with. Marek has that quiet, annoying Czech politeness, so it was impossible to tell. Personally, I had to go through several upsizings of amps and grungy key combinations before I could match the intensity of the other lads.

The symbolic starting point for me with the Souls was working on the song ‘Never Drops’ which never made it onto the ‘Mind Stroll’ album. The album title ‘A 1000 Tears’ was to be “Never Drops” for a while. I saw it as continuing on thematically from ‘Mind Stroll.’

The song ‘Grey Street’ was also an early starter along with ‘A Thousand Tears’ and ‘The Fear Time’. Kevin is not a chord-chart man, so it took a while to rewire his brain to get used to memorizing prog-style stuff. Then he let me into a secret – he was a “Rush” and “Yes” tragic. So any sympathy I had for his struggle disappeared. “If Geddy can do it, Kevin, you can do it”. “How would Chris Squire play this?” I had a lever.

The style of Souls of Ambience comes from encouraging the band to provide a thick blended grungy sound at all times. I played the lads Velvet Underground’s ‘Venus in Furs’ and Jefferson Airplane’s ‘Law Man.’ I love the raw stoner-looseness of both these songs. Lou Reed said somewhere, “Don’t overproduce it.” My wife tied me to a chair and played me “real” Leonard Cohen and the “hated” overproduction Phil Spector later brought to Cohen’s recordings. Memories of the huge sound and immense fun I had playing in For Madman Only came to the fore. And the anger and sadness I felt that coagulated into songs such as ‘A Thousand Tears,’ ‘The Fear Time,’ and ‘Grey Street’ bubbled up and made me play harder and louder.

Could you share the genesis of the concept behind ‘a 1000 Tears’? What inspired the narrative thread weaving through the album, and how did you approach translating these themes into music and lyrics?

Listening to ‘A 1000 Tears’ as a concept album, the downward-spiral story of a young woman who “…knew she wouldn’t make it…” is a thread. Attempts to protect her younger sibling from abuse by their stepfather “…I knew what I had to do, dressed myself in black, waited in the bedroom knowing he’d be back” … “Mum is floating elsewhere, tears trickle down her face, she says don’t worry baby, nothing hurts me anymore…” leads to the child’s determination to fix the problem “… is your name avenger, will you walk with me, burning all before you who’ve abused children…”. Her stoner stepfather has his own problems “… Didn’t know I would snap, so maybe the weed was packed too tight, I don’t know, I was happy, then bang I’m screaming and kicking things…” Running away from home, the young siblings find themselves on the infamous Grey Street, St Kilda. “… Grey Street where’s my innocence, did you take me walking there by chance, does evil favor most the lost, or am I just one of the lucky ones…” While there are many street people who share the same story on Grey Street, it is a dangerous place. “… Hey Mary, those two runaway kids, Sam said she saw them sleeping under the pier. Dangerous down there, some weird guy hanging around…” Things go from bad to worse. “… Grey Street she was family, now those left say you’re all I have, that every drunken leather face and all the girls you’ve killed are sisters” … “The angels came but she’s really gone, the lurching faces now dissolved away…” After her last breath, things improve greatly “… she’s flying now, her face lit up by summer rain…” The girl gets a bit of direction from the beyond: “… Look, over the horizon is a land of infinite light, You should try to go there now” … ” Gone completely beyond, to the other shore…” Meanwhile, stepdad, sad and lost, senses her presence “… What is this wind, flying around like some magical dancer?…” Anyhow, this is one way of telling the story.

Were there any particular influences or artistic approaches that shaped the album’s sonic landscape?

Building a hard, edgy musical feel that honors the often sad stories underpinning the lyrics was central to everything for me. As soon as I felt the gel and realized the power we could all generate together, I became a total Souls of Ambience member. We are collectively doing something different. I love it.

During the early period of Souls coming together, I was listening constantly to Montiverdi’s ‘Vespers,’ taken by the always shifting theatrical dynamics of the work. I’d been working on a Baroque choral/orchestral work for a year or so called “This Empty Field” and was still in that creative mindset when I began working with Kevin. It was quite a relief to unwind the brain and get back to simple modal jamming after the precision of classical counterpoint. Now when we rehearse, I feel I really am where I want to be musically. It is a real blast to play with the lads. They are so good.

Collaboration often plays a crucial role in band dynamics. How did your collaboration with Kevin Kershaw, Marek Taborsky, and Chris George contribute to the creation of ‘A 1000 Tears?’ Can you share any memorable moments or challenges encountered during the recording process?

We had interviewed a couple of engineers before settling on the legendary Dan Murtagh who recorded and mixed ‘A 1000 Tears.’ I didn’t realize how locked into working with click-tracks standard recording methods have become.

When we met, I explained to Dan we were not a click-track kind of band. “It’s about the feel, man.” Dan thought we were crazy and somewhere in the middle of the tracking sessions, I suspected he was right. Each take of the backing tracks was different. We sped up in some sections, slowed down in others. There is one breathtaking moment on the album where we come out of a pause and the tempo drops dramatically. It sounds kind of weird, but it is pure Souls of Ambience. This method was hard to manage technically for Dan. I think we were all a bit stunned how well the wild-style tracks ended up. Similar to a live recording – accepting the bed, knowing it was not perfect, but moving on.

I asked Jerry (drummer, Men At Work) to have a listen at Dan’s to our final mix candidates. He had some useful suggestions which improved the mix. Jerry asked how long I took to lay the lead vocal lines. He couldn’t believe it when I said all tracks, about 2 hours. I mean man, the album only goes for 42 minutes, why would we take more than two hours?

Souls of Ambience are a family. Minor irritations between siblings simply disappear when we hit the first chord of the day together. Such a big sound, it is epic to play with these guys.

On the subject of family, I have to mention Angelo, Tanya, Cathy, and Tim. The support we get from our four crew-of-friends is exceptional. I always play better when one or more is present even at rehearsals. They believe in us and in the musical stories we are presenting to the world. I have to do my best to live up to that support.

Now that ‘A 1000 Tears’ has been released, what has been the most rewarding aspect of sharing this album with listeners? Are there any tracks or moments on the album that hold special significance for you personally, and if so, why? Additionally, what’s next for Souls of Ambience following the release of this debut album?

In Australia, we live in a surreal world of denial about domestic violence and the profound impact it has on countless silent victims. Each time a woman is murdered at the hands of her trusted partner, politicians flurry around and promise to fund services and do all sorts of things to make a difference. Then yet again, the media moves on and nothing happens. Many years ago, sitting with a circle of ten women prisoners, a decision was made to produce a play with songs about the cycle of domestic violence, drug abuse, and attendant crime. Most of those women are now dead. I am still telling those stories.

We are working on new songs and feels that will become the next album. Haven’t discussed this at length with the lads, but I suspect we will record some long-format works in a proto-punk/prog style. Who knows?

What are some of the most important players that influenced your own style and what in particular did they employ in their playing that you liked?

The huge keyboard sounds of Jon Lord, Rick Wakeman, Brian Auger. The mysterious modal melodies of Iron Butterfly and the Doors. The melodic perfection of Oscar Peterson. The wacky impossible style of Thelonious Monk.

I think of Monk each time I scream up the waterfall keyboard hoping to land on the correct chord. Sometimes I do, many times I don’t. But like divining through throwing dice, the “wrong” chord becomes creative stimulation for the beginning of the next improvised section. I think Marek (guitarist SOA) hates it. He is such a perfectionist, working out each of his beautiful solos and then playing them the same each time. A normal conversation when I present a new song to the band goes like this:

Marek: “So what do you want me to play?”

Greg: “Just solo, loud, all the way. Kevin, here is the bass line I wrote.”

Kevin: “Maybe not. I hear it more like this.”

Greg: “Chris, can we take it a bit slower? More poignant.”

Chris: “Sure.”

Then we play the same big and fast version as before. I give up with a suitable amount of grumbling and gnashing of teeth. And then the song skeleton I presented finds its breath – and another uniquely Souls of Ambience song is born.

Have you found something new lately you would like to recommend to our readers?

Being easily influenced, when in a writing phase I don’t listen much to other people’s music. The exception is when researching “feels” as distinct from songs. Listening to the gutsy stage-poetry of Patti Smith gives me courage to incorporate evocative spoken word. The mesmeric trance-like feel of the Doors and Velvet Underground often comes to mind when Souls are jamming. There’s a bravery in Nick Cave’s work that I admire; he just does what he feels like doing, love it or hate it.

I think some of our long psychedelic jams are some of the best work we do. Maybe we’ll get a chance to play long sets someday before an audience of chilled stoners. There’s a whole other side to Souls of Ambience music, we’re just getting going.

What else currently occupies your life?

Becoming comfortable with the strange transitory nature of everything within the mad clanging of global doom-drums. How can humans not see climate change as the scariest thing humanity has ever faced? Commit violence towards children? Turn the other way as one country openly insists on their right to extinguish the lives and nationhood/statehood of another country in order to benefit themselves and their horrific view of what God wants? What kind of God allows newborn babies to die violently? These thoughts occupy my mind, which occupies my life.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Life is short. The time from when, as a late teenager, one begins to realize what reality is, through to the time when inexorably the world begins to fade – then is completely gone – is really so short. This is everyone’s experience but is never spoken of.

The creative artist in each of us should be imagining our experience of whatever our view is in every moment, ceaselessly until our last breath. There is no right or wrong. It just is.

Klemen Breznikar

Soul of Ambience Official Website / Instagram / Bandcamp