Asgard | Stow Lake | Songs | Interview | Bob Hardy | “Lost Recordings from Acid Rock Era”

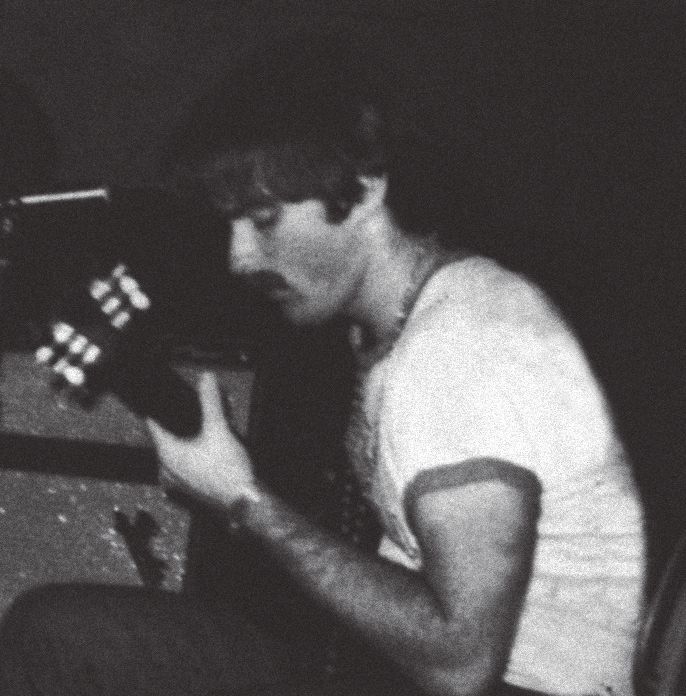

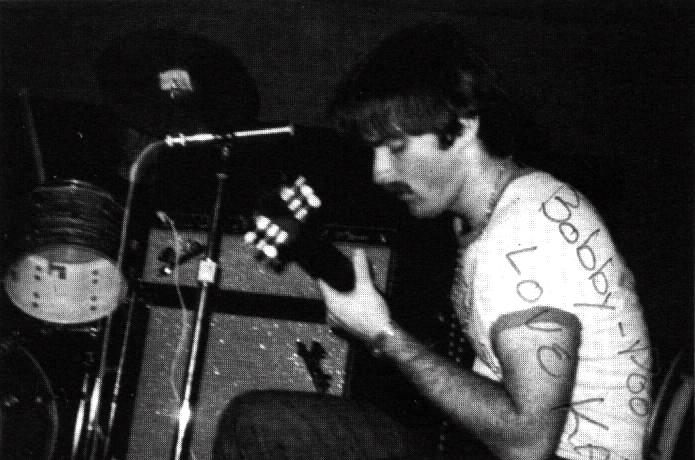

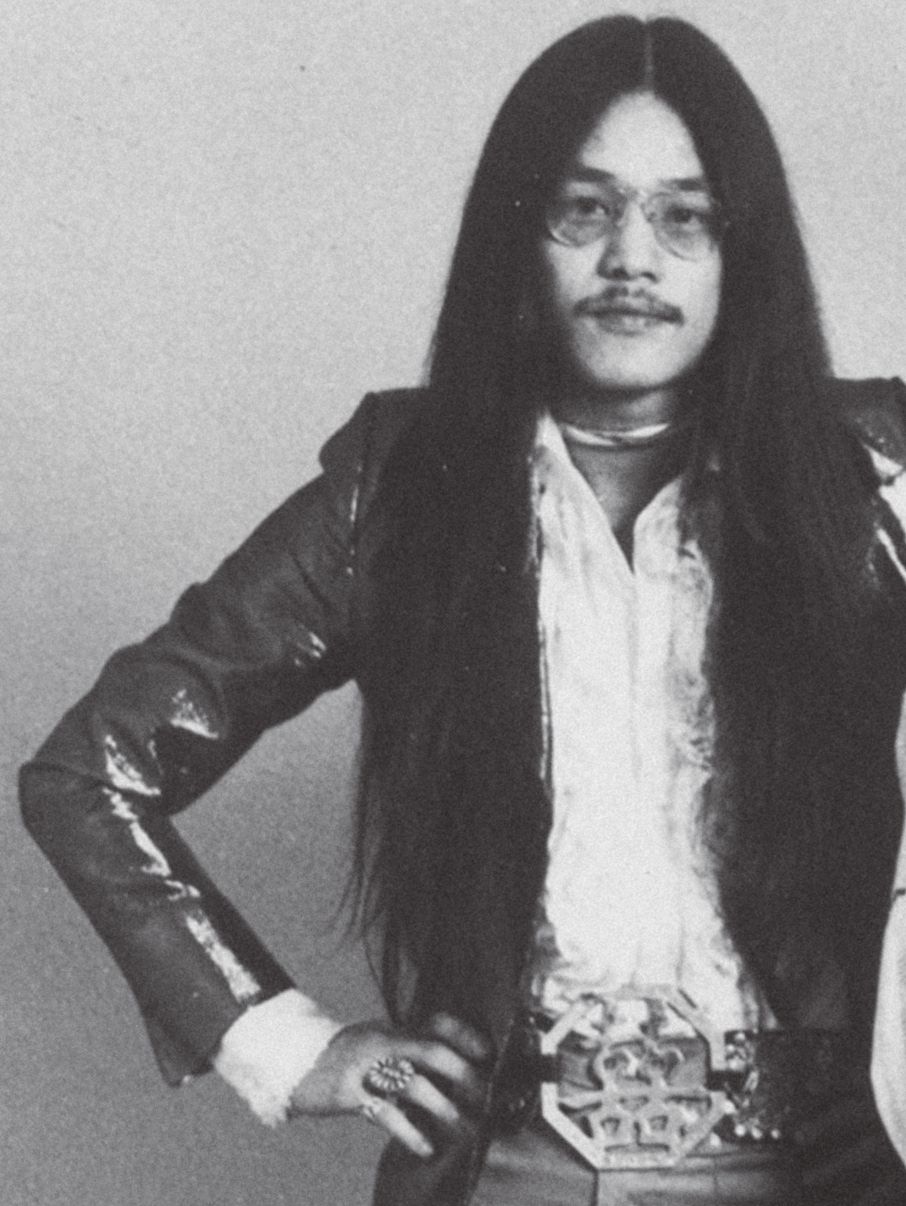

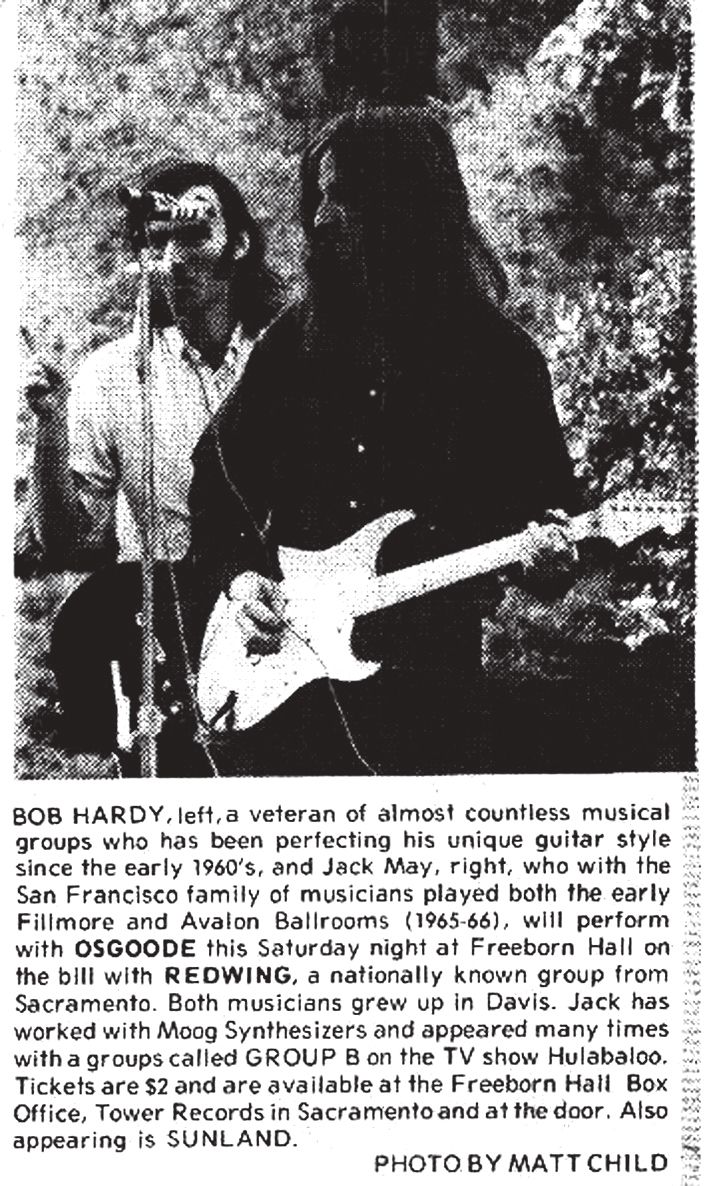

Bob Hardy is a veteran guitarist of bands since the garage days in San Francisco and later on a versatile member of Asgard, Stow Lake and Songs to name a few.

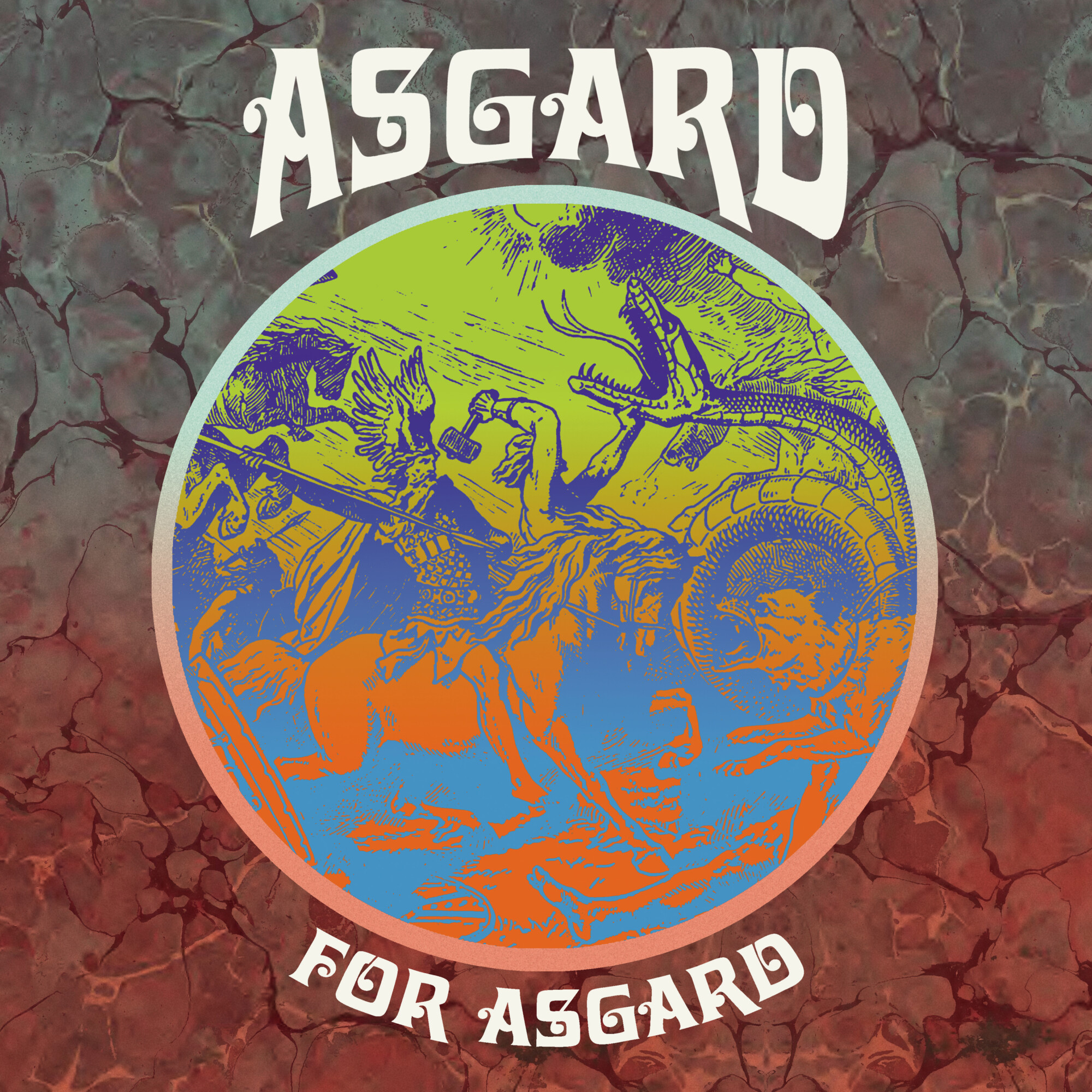

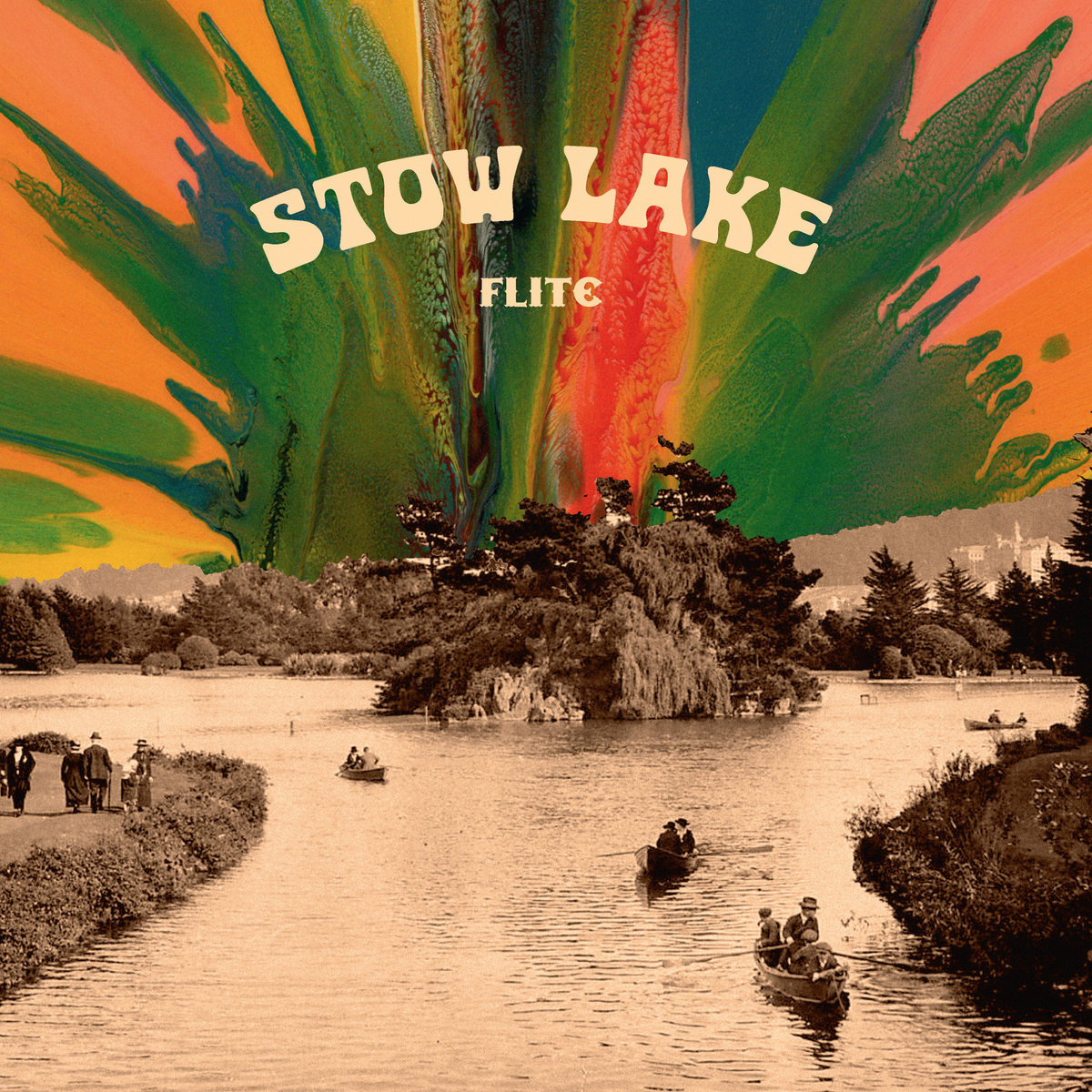

Asgard was initially known as Osgoode, named after the street where Blue Cheer had their headquarters. It was a unique band featuring an electric violin player / vocalist of Asian origin named Jake Gelon Lau, who played later in funk bands like Gideon & Power and Tribe, Jack May on guitar and occasional vocals, Phil Robyn on bass and occasional vocals, Steve Hall on drums and vocals, and Bob Hardy on guitar. Out-Sider (Guerssen imprint) recently issued an unreleased album by Asgard which was recorded in 1972. What we have here is a hard acid rock band playing many gigs around the Bay area. Out-Sider also issued two more unreleased recordings from bands featuring guitarist Bob Hardy; Stow Lake and Songs. Stow Lake was a seven piece group named after the lake in Golden Gate Park composed of well-seasoned musicians from the original San Francisco scene. Among them, we can find ace guitar player Bob Hardy; the tandem of Jeff Ervin (sax, flute) and Jean Hintermann (trumpet), both later on Aura, Bill Withers’s backing band and Hot Cider (with Dennis Geyer of A.B. Skhy); child prodigy Larry Mallarino on trombone and bass player Dave Dunaway (later of jazz fusion band Listen). Not forgetting powerful singer / organist Bob Staley. Unreleased until now, the recordings contained were registered at top studios like McCune and Golden State Recorders. Also included are a couple of excellent quality live tracks recorded at the legendary Fillmore West in 1971, showing the band at their peak with an impressive jamming / acid-rock sound. While Songs was a West Coast acid-rock, psychedelic trio formed by three versatile and well seasoned musicians: Bob Hardy , Tim Timmermanns (John Cipollina’s Freelight, Craig Chaquico’s band…) and Chris Quinn. Between 1973 and 1975 they recorded at their home studio several tracks that never saw the light of day until now.

“It’s mostly leaning toward psychedelic rock, and some of the lyrics hark back to the protest song days of the folk music era”

I would appreciate in-depth replies.

Bob Hardy: Not to worry! I got a gold medal for journalism in high school, and a few published articles and such since. I’m familiar with the value of a good editor, and wouldn’t object to whatever preening you are inclined to give. No need to apologize for any improvements you may see fit to make.

Would you like to tell us where you were born and what could you say about your upbringing?

I was born in the Sacramento area of California to very young parents. One set of grandparents lived nearby, so I spent a lot of time with them throughout my childhood and young adult life.

What did your parents do and when did you first get interested in music?

Dad worked in a bank, and Mom taught dancing at an Arthur Murray studio. I was interested in music from very early childhood. I had a little phonograph of my own, and a collection of Little Golden Records. But I was also aware of the adult pop music that surrounded me. My grandmother had played piano at silent movies, and my grandfather started teaching me ukulele when I was 7 or 8. The small fretboard was perfect for a kid’s small hands… I taught myself to play the jew’s harp – my dad had a good one – and got to be fairly adept with the ocarina. In elementary school, I took two years of violin lessons, and in middle school, two years of drums. Neither one of those would stay with me the way the guitar would, soon after. My mom had a student model guitar which she never really mastered, and it was available when the time came for me to take it over.

Do you recall a certain profound moment when you knew you wanted to become a musician for the rest of your life?

Not exactly, but there was a “turning point” moment. I had been teaching myself songs on the ukulele by ear, but when I heard ‘Pipeline’ by The Chantays in 1963, I was inspired! The problem was, it sounded stupid when I tried to play it on the ukulele. So I picked up Mom’s guitar and taught myself to play ‘Pipeline’ on it. It took a month of intensive practicing, but I finally got through it without making a mistake. I’d never had a lesson, so I had to invent all the chords for myself to play, which fortunately are not too far away from ukulele chords.

What are some of the very first high school bands you were part of? Did anyone record a single or are there any unreleased recordings left?

There are no recordings of the very early stuff, which I consider a blessing! There was Woody’s Five, which was mostly lip-sync except for me: I was playing borrowed drums at the time. Then The Victors, followed by The Ceruleans, which eventually morphed into The Original and Highly Superior Benedick’s Illuminated Mixmaster, or Benedick’s Mixmaster for short.

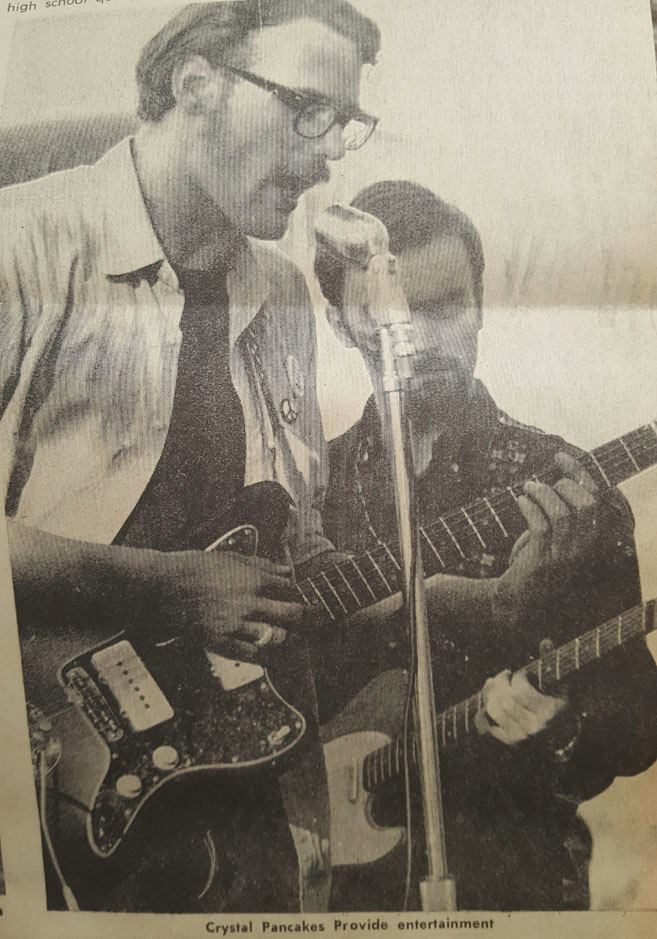

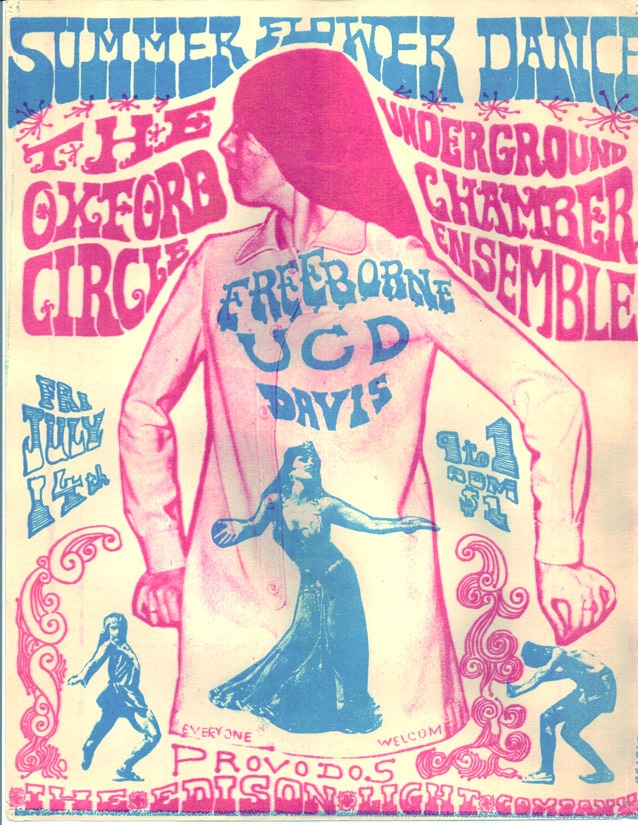

We played at many of the area high schools, even though we weren’t in high school yet ourselves, and several times at the Teen Fair in Sacramento at the State Fairgrounds. There are some rough recordings of that band, made in an educational TV studio on campus at UC Davis, which was normally used for shooting veterinary training films, so the audio equipment was beyond crude. After The Benedick’s Mixmaster came The Underground Chamber Ensemble, a jazz-rock trio; and then The Crystal Pancake, which was a power trio, and that eventually was renamed Wakeforest.

Where did you first meet Christopher Quinn?

We met in a philosophy class at American River Junior College. We didn’t immediately hit it off. He was a bit adversarial at first, but we discovered that we weren’t really so very different in our musical tastes and sense of humor, and became better friends. That was when I encouraged him to consider performing music, which he had never done. It was convenient enough though: his step-father was managing a large local music store, and Chris Quinn had been working for him as a piano mover. His dad also owned a nice Martin acoustic guitar, which Chris learned to play enough to write a few songs on it.

Tell us about Good Medicine.

Good Medicine was basically four guitar players, most of whom also sang, and Chris Quinn, who was a singer who played a little guitar too. The folk music craze of the ’60s had largely died down, but we all knew of The Byrds, Jefferson Airplane, Bob Dylan, Donovan, and Crosby, Stills & Nash. We played at local coffee houses and radio stations, as the “free form” FM station was newly arrived on the scene and quickly becoming very popular. Many of those radio stations experimented with live performances on the air, which was easy for us to fit in with, being mostly an acoustic act with no drums or high volumes. We actually had two electric guitarists, one of them being me, but we always played quietly enough that the acoustic guitarists and vocalists could still be heard.

“It was pumping!”

How would you describe the music scene back where you lived in the mid to end of the 60s?

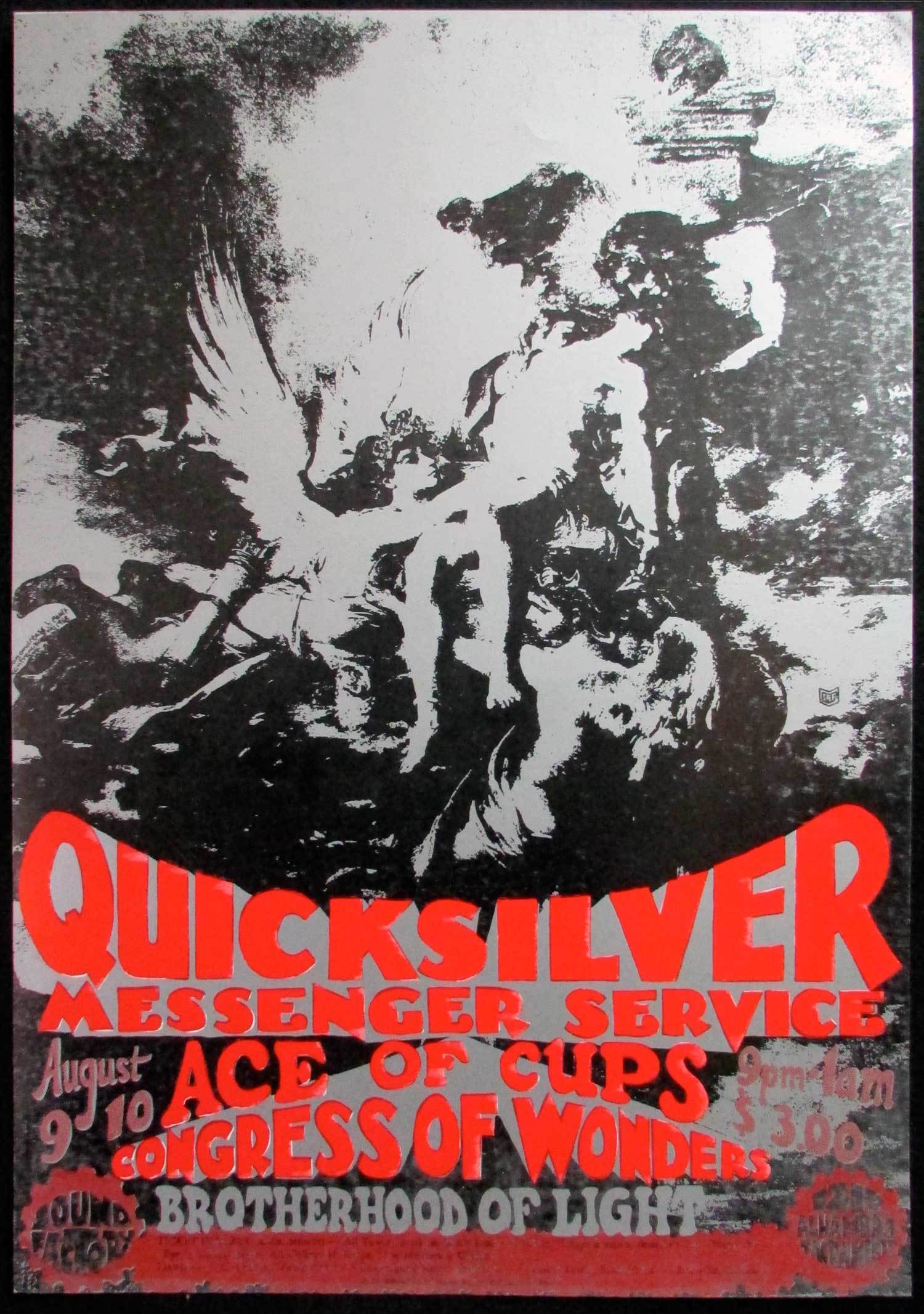

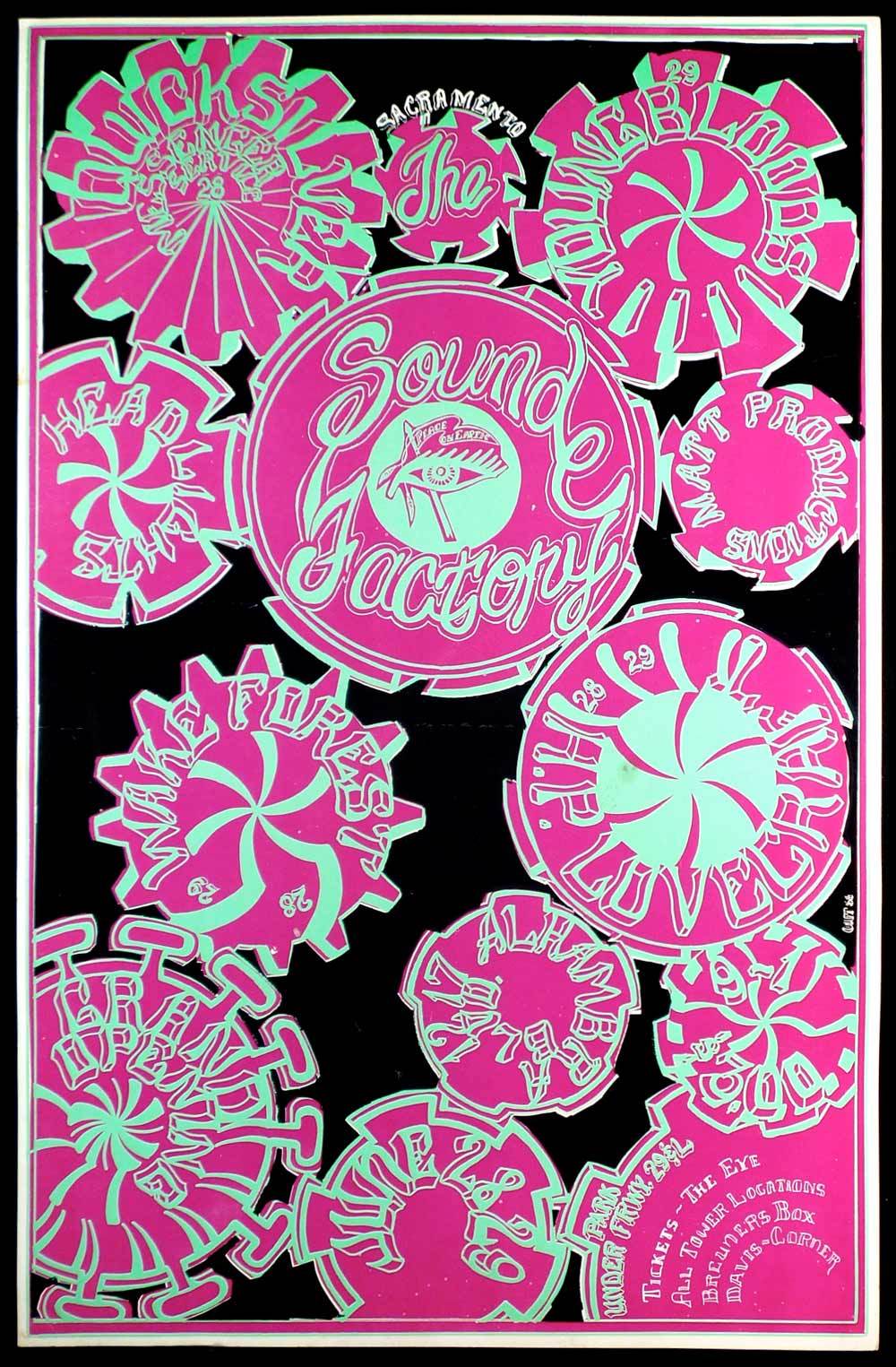

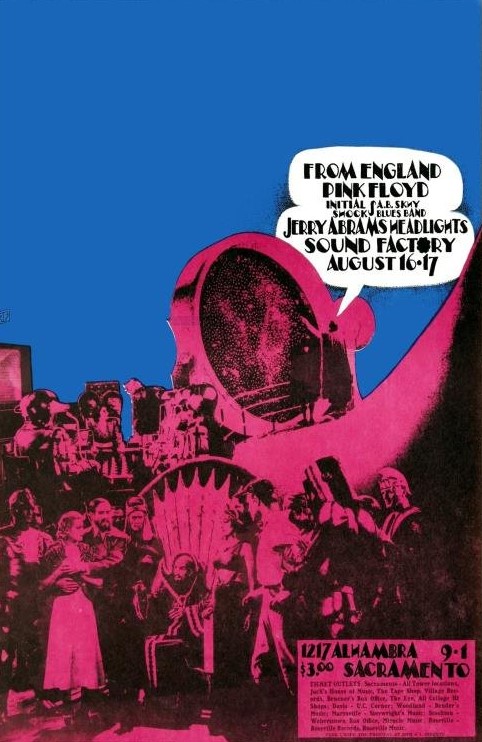

It was pumping! The Sound Factory had just opened in Sacramento in June ’68: we (Wakeforest) were the opening act. Friday night, the headliner was Quicksilver Messenger Service, and Saturday night, The Youngbloods. We would play with quite a number of acts over the next year and a half, including Pink Floyd, Spirit, Country Joe and The Fish, The Chambers Brothers, and many more. I had friends in Oxford Circle, KAK and Blue Cheer.

What led to the formation of Osgoode and how did the band transcend into Asgard? What’s the story behind the band name and who were the band members? Did the band go through any lineup changes?

Osgoode was a band that already existed in the Berkeley area, across the San Francisco Bay. They were in need of a lead guitar player, and my friend Jack May brought me in to audition. The other members were Gelon “Jake” Lau on electric violin and vocals, Phil Robyn on bass and occasional vocals, Steve Hall on drums and vocals, and Jack on guitar and occasional vocals. (Gelon is pronounced “JAY-lon”, but he goes by Jake these days.) The band had taken its name from Osgoode Place, which was where the Blue Cheer business office was, a tiny street in San Francisco’s North Beach district. Jack May and I used to visit there fairly often, so there was a certain continuity to borrowing the street name for the band.

Tensions were growing inside Osgoode and came to a head while we were recording the album. Jack May was musically not keeping up with the rest of us. Ironically, I probably made him look worse by comparison, even though I wasn’t deliberately competing with him. This was true in our regular performances, but it was harder to ignore in the studio, where everything was under more intense scrutiny. Jack’s vocals don’t appear on any of the songs, including his own, and I played his guitar parts on most of the recordings.

The rest of the band decided, over my objections, to drop Jack from the band, so we soldiered on, now calling the band Asgard. In spite of my ambivalence about firing Jack, we did get musically better. The arrangements got more polished, the vocals stronger. When we started recording at Roy Chen Recording in San Francisco’s Chinatown in early 1972, we were still Osgoode, but by the time we finished a few months later, we were Asgard.

You were from the San Francisco area, there was a lot of happening back then. Did the counterculture and the whole hippie revolution inspire you as a band?

Oh yes, definitely! There was no way to avoid it – not that we tried to avoid it! And of course, we were influenced by other bands that featured violin, such as It’s A Beautiful Day and Kaleidoscope.

What clubs did you like to visit back then? What are some memorable acts you saw?

We played a lot of clubs, so we didn’t often go to them just to “hang out”: at least, I didn’t. That was our workplace. But I did see a lot of other acts, both at places we played (Asleep At The Wheel, Tower of Power), and places like The Fillmore Auditorium, Berkeley Community Theater and Fillmore West (Pink Floyd, Frank Zappa, B.B. King, Booker T. & the M.G.’s, Albert King, The Who, et cetera).

Tell us how you first heard of Blue Cheer and what was your connection with them? I’m asking since you were named Osgoode, after Osgoode Place, a tiny street in North Beach where the Blue Cheer offices were located.

That’s right, but actually the roots go back further than that. There was a local (Davis, CA) band in the mid-’60s called The Hideaways. They were a few years older, and all went to my high school. The Hideaways eventually turned into Oxford Circle. I knew them all, and they sometimes rehearsed just down the block from where Benedick’s Mixmaster rehearsed. I taught them ‘Nowhere Man’ one afternoon! Paul Whaley, the drummer, would go on to be Blue Cheer’s drummer, and Gary Yoder, the front man and lead singer, would eventually lead Blue Cheer when they had their big personnel changes in the early ’70s. My friend Jack May from Osgoode had earlier been in a group variously called Group B, or The Spokes, with the Peterson brothers: Dickie Peterson would be the bassist and vocalist for the early Blue Cheer lineup, so we had Blue Cheer connections in several different directions.

Osgoode began in 1971?

Yes.

Who left the band when they started playing as Asgard in 1972?

Just Jack May. Everybody else remained through the end of Asgard.

Tell us about the material you recorded in January 1972 at Roy Chen Recording in San Francisco’s Chinatown, and was finished by Asgard in March.

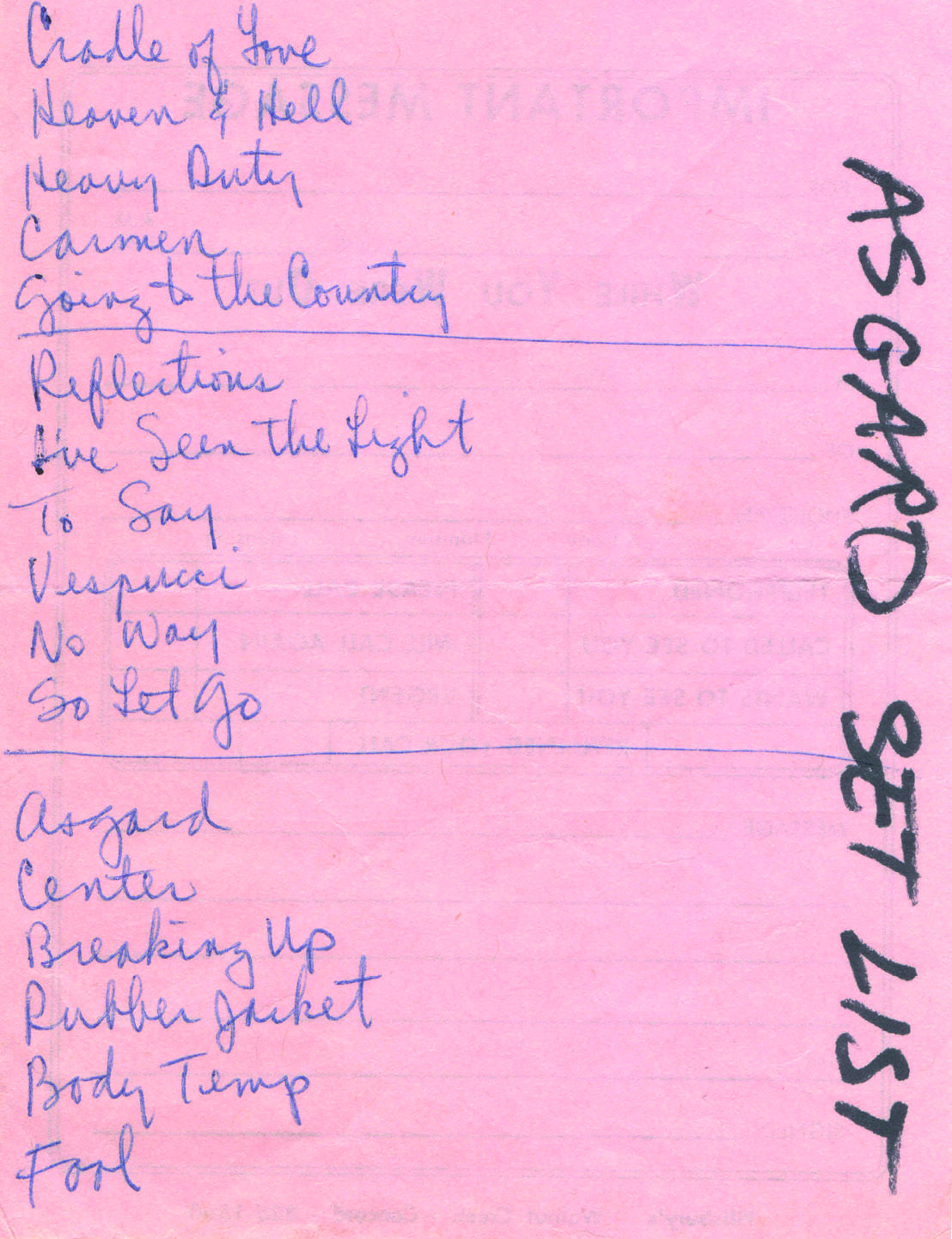

Much of it was written by Gelon/Jake, some by me, with and without co-authors, and one by Jack May. It’s mostly leaning toward psychedelic rock, and some of the lyrics hark back to the protest song days of the folk music era. The chemistry between Phil Robyn (bass) and Steve Hall (drums) was at times dazzling. When I listen to ‘So Let Go,’ even after all these years, my favorite part is when everything drops out but bass and drums, and I do that chordy riff over the rhythmic bed they laid down. For me, that’s what makes that recording something special. That mood, that groove – it’s just so right!

What kind of gear, amps, effects et cetera did you use?

In the beginning, I had a Gibson SG and a 100-watt Marshall head, which I used with a Cry-Baby and a blue-green FuzzFace, and an unbranded wooden speaker cabinet with two 15″ speakers in it and a “High Voltage” sign attached. I soon traded off the SG, switched to a ’63 Strat, and added an Echoplex. For several of the songs (notably ‘If I Had Anything To Say’ and ‘Your Mouth Tastes Like You Just Woke Up’), we borrowed a Leslie speaker for my guitar. The rhythm guitar on ‘So Let Go’ is just the Marshall pegged, with no pedals added, and back then, no master volume: just dimed! A few were done with a direct box, which I always thought were going to be replaced with “real” guitar tracks, but some never were, like on ‘Reflections’. That was never meant to be the final take, but in the end, it was.

What are some of the memories from recording there? Who was the producer and how long did it take to record?

I tend to think of myself as the producer, in that there were all-night mixing sessions where everyone else would have fallen asleep by the time the track was done. But Gelon/Jake and Phil Robyn definitely had their input into the process too, so I can’t claim full credit. The whole project took about three months in the studio.

We used to come into the studio when we could get some time. We were paying a reduced rate for “off hours,” while other acts who were paying a higher rate got priority. Dr. Hook & The Medicine Show got first dibs on studio time, and we got the leftovers. That worked out fairly well for all concerned, as the Dr. Hook song ‘Sylvia’s Mother’ was initially recorded at Roy Chen Recording, and later finished up at a more posh studio.

We were in Chinatown, so were within walking distance of several food opportunities, particularly a Chinese bakery that was quite close. I remember feasting on the black bean, red bean and yellow bean bao during those long, late night sessions.

One memory that comes to mind was recording the vocal for ‘So Let Go’. I had not settled on a final approach to it, and was feeling a bit unsure about how to do it. Jack May had an idea. He went out and bought a little bottle of scotch – I think it was Usher’s Green Stripe – and had me drink it all. This ripped up my throat a little, but also loosed up my reserve, so I just let the song tear up my voice, and damn the torpedoes! Later, I would slip into that vocal mode more-or-less automatically when we performed the song live. That vocal delivery stuck with that song, beyond the studio sessions, and no longer required scotch!

Did you have an album artwork in plan as well? What were the circumstances that the record wasn’t released?

Artwork, not really. We were thinking whatever we did, the record company would probably overrule it, so we might as well let them provide something they liked. In the end, we shopped the tape around, but got the dreaded voice of the A&R man: “What else have you got?” They liked us, but not not enough to commit.

Did you have a demo / acetate out so that you could send it to the labels and/or radio stations?

There was a demo tape of Osgoode, just some snippets from live rehearsals. I still have it. It’s more fragmentary than the studio tracks, and more crudely recorded. Only two songs were somewhat more polished, having been done at the Fantasy Records studio in Berkeley, and neither of them are complete versions on the demo tape. It was mainly the Asgard studio tape that we shopped around, and got some nibbles, but no bites.

Would love it if you could share some further insights about the material featured on this unreleased album.

‘Carmen’ (Lau)

Carmen was, as I understand it, a girl that Gelon met while he was selling hot pretzels on the University of California at Berkeley campus. I don’t know if they ever became “an item,” but obviously Gelon was thinking along those lines. There were no phaser pedals at the time, so the effect on the guitar is done with an outboard, manually controlled device in the studio.

‘For Asgard’ (Lau)

This became our theme song. I’m playing pedal steel guitar on it toward the end, which I had borrowed for the recording. There’s also some of that Leslie speaker and Echoplex sound in there.

‘Your Mouth Tastes Like You Just Woke Up’ (Hardy-Harkens)

My friend and collaborator Bob Harkens (aka Shredni) came up with many of the lyrics, and I added some. The music is also a combination of his contributions and mine. It’s kind of a wistful look at what we used to call ecology, and which has become even more timely since then. The lyrics dangle between funny and not-funny, which we tended to do a lot when we wrote together. More Echoplex and Leslie on the electric guitar.

‘Vespucci (The Dutiful)’ (Lau)

Gelon’s acerbic look at American patriotism, which tends to be overly narrow in scope, and historically slanted. It’s also got environmentally based commentary, but angrier than ‘You Mouth Tastes Like You Just Woke Up’.

‘Fool’ (Lau-Robyn)

This was one of the songs that Osgoode was doing in some form before I came aboard, so I can’t say too much about writing it. It was one of the songs we did on the Fantasy Records demo, only in a more pop-flavored version than the one on the album.

‘So Let Go’ (Hardy)

My attempt at encouraging the listener to “hold on loosely,” with a decidedly psychedelic and mildly philosophical twist.

‘If I Had Anything To Say’ (May)

Possibly the best thing Jack ever wrote, and certainly my favorite of his. In the end, I sang the verses, and Gelon and Steve Hall joined me on the choruses. It was a good one to do live, because it had more dynamic range than most of our material. It was nice to have a gentler moment in our live shows, in between all the blast and bluster.

‘You Raise My Body Temperature, Baby’ (Lau)

As good as this is, later on we slowed the tempo down a little, and got into a more pelvic groove for our live performances. The vocals got even more powerful too, but unfortunately there were no studio recordings of this song in that form.

‘Center of the Sky’ (Hardy)

I wrote this originally in 1968 or ’69. Wakeforest used to do a version of it, but by the time of this recording it was much more highly evolved. During part of the cadenza (the unaccompanied solo), you can hear me singing a harmony part against my own lead guitar, which was so loud that we were able to use the vocal mic for both the guitar and the harmony.

‘Reflections’ (Lau)

Gelon’s big cadenza is the intro and outro, for which we used the outboard phaser effect that we’d used on guitar elsewhere. Steve Hall sings the lead.

Did you do a lot of shows? What are some clubs you played? What are some bands you shared stages with?

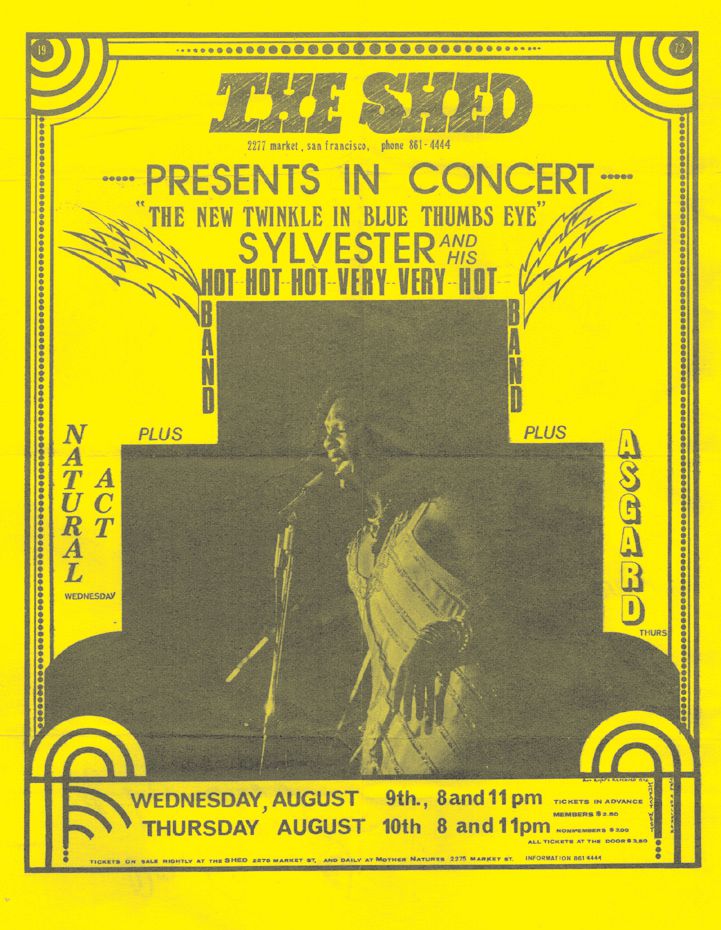

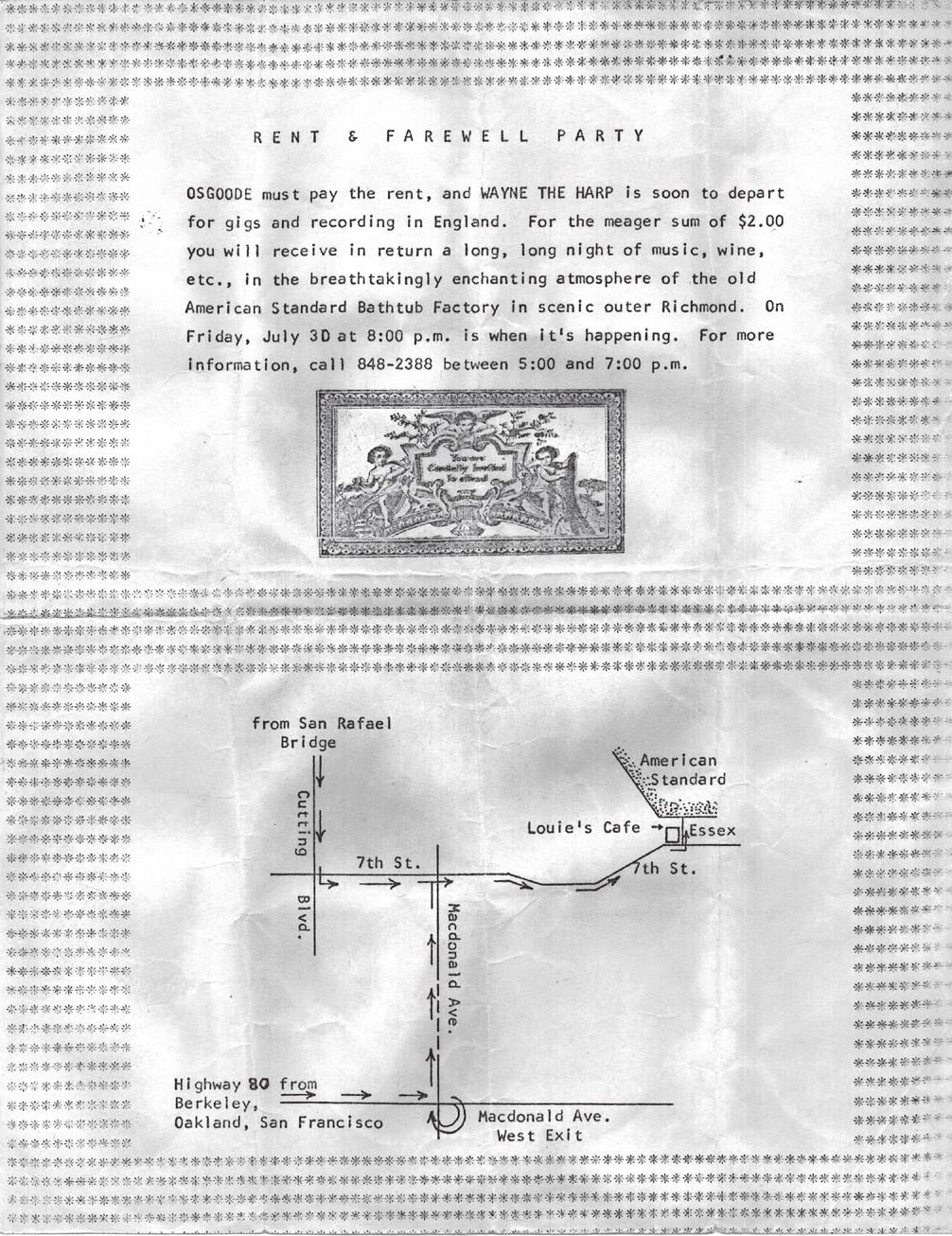

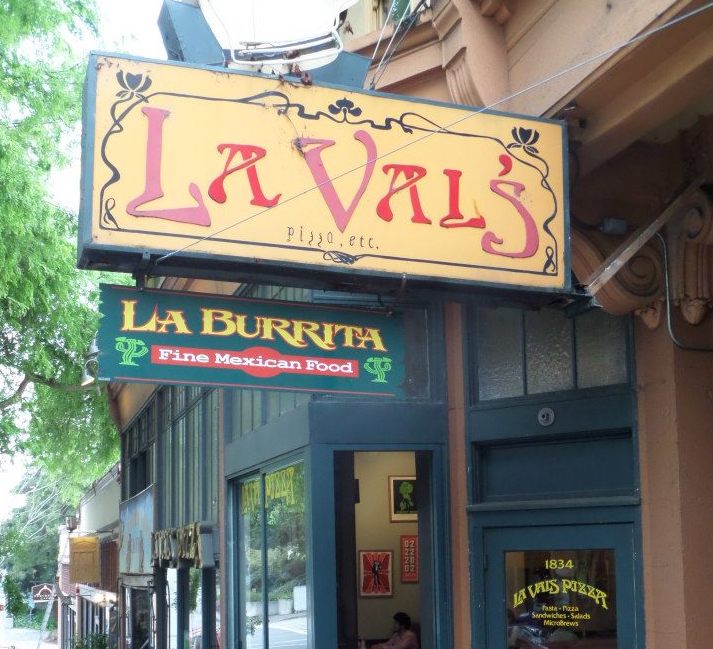

Yes, we played at The Shed, The Stud, The Clement Mixer, The Bojangles, The Longbranch, and most of all, LaVal’s Pizza in Berkeley. Most of those were “one night, one act” clubs, but we did play with Asleep At The Wheel and Tower of Power at the Longbranch. We played at The Shed (and possibly others) with Sylvester and His Hot Band. We played a weekend with Luis Gasca (of Malo and Azteca). We used to share a rehearsal space with Wayne The Harp, which was a later lineup based on AUM, and some of whom would later yet become parts of Heart and the Ronnie Montrose band. They played at a rent party we threw in July of 1971. Our rehearsal space had been a warehouse at the American Standard bathtub factory in Richmond, CA.

Where did you have your jam space?

One was that bathtub factory warehouse in Richmond, where I wrote ‘So Let Go,’ and all of our early formative work was done. There was another one in a storefront in the Mission District of San Francisco, and later, another one in Albany, on the far side of Berkeley.

And what would be the craziest gig you ever did?

I guess I’d have to mention two: you can decide for yourself which should be craziest. One was when we were playing a 2AM-6AM gig at The Shed. Outside, the street was lined with paddy wagons and police cars: they were waiting for a violation of an old ordinance that prohibited dancing in San Francisco during those hours. It was really just an excuse to shake down the largely gay audience and shut the club down, so we played a 4-hour gig with no danceable beats, really a challenge to come up with that much music that wasn’t danceable. But in the end, although it was grueling, we won out: no busts happened that night. On that night, a guy in a dress with really haphazard lipstick came up to me and asked if we would take requests. I started to explain about the cops and the need to play undanceable music, and he unbuttoned the top of his dress, pulled out a bunch of red plastic peppers and waved them at me, and said in a high falsetto voice, “How Much Is That Doggy In The Window is danceable??? Woo woo!” Then he sort of danced off down a nearby staircase, and I never saw him again. There was another guy in a furry loincloth who came up to me with a big laboratory-style glass bottle and offered me a sniff of his amyl (nitrate), which I politely declined.

The other would have been one of the nights we played at The Bojangles with Luis Gasca and friends. This guy I’d seen before (with the bottle of amyl) showed up on the dance floor, a bit overdressed even for a chilly San Francisco evening. He gradually shed layer after layer of attire until he got down to the fur loincloth again, at which he was “invited” to leave. It looked like he was seriously considering shedding the last of his clothing, and the club bouncer decided he wasn’t going to do that.

Did you play with Blue Cheer as well?

Not exactly. Some of the guys came to visit during an earlier recording session at Roy Chen’s, before the Osgoode project, and played on some of the tracks we were doing at that time. It wasn’t anything officially connected with Blue Cheer, just many of the same guys.

How long was the band around and when did you decide to stop?

I don’t know when we first started, but it would have been around Spring of 1971. We broke up around the Fall of 1972.

Since you were from the epicenter of “happening,” did you experiment with psychedelics? Did that have any impact on you as a musician or/and as a person?

Ha! Well, I, uh… yes. And yes. My first such experience (but not the last) was with morning glory seeds. I had little idea of what it would be like, and was surprised at its intensity and vibrancy. The lyrics of ‘Center Of The Sky’ are more than a little influenced by a psychedelic state of mind, among others. Certainly ‘Your Mouth Tastes Like You Just Woke Up’ has some of that luminescent, even hallucinatory quality.

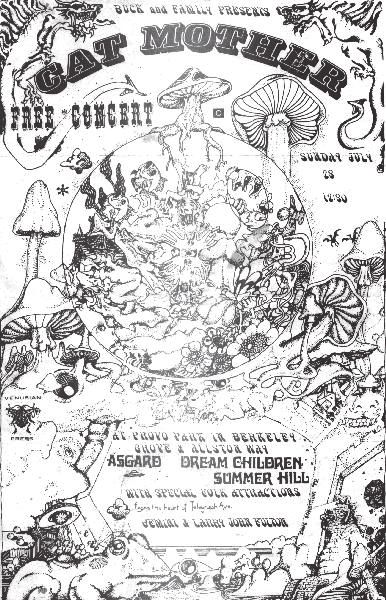

Tell us about the Provo Park gig in Berkeley, California, on July 4th, 1972

It was perhaps our last best hurrah, although not our last performance together. We had a sunny, warm day, and I did the Jimi Hendrix version of ‘The Star Spangled Banner’ in honor of Independence Day. We rocked hard! It was a big crowd, and a good crowd, the kind of outdoor gig that one hopes will come now and then.

How did Stow Lake come about? Who were members of the band? That was even before Asgard, right?

Yes, immediately before. Honestly, I don’t remember how I got involved, except that one of my very first duties was to play on the McCune Sound demo tapes. I’d never heard the material before, and I borrowed a guitar and amp, no pedals, so the recorded sound is pretty vanilla. I think the recordings are generally pretty good, in spite of my not knowing my way around the material. I never knew what they were doing for a guitar player before me, but I presume there was one! Everybody else certainly knew the material already. I was still reading the changes off index cards.

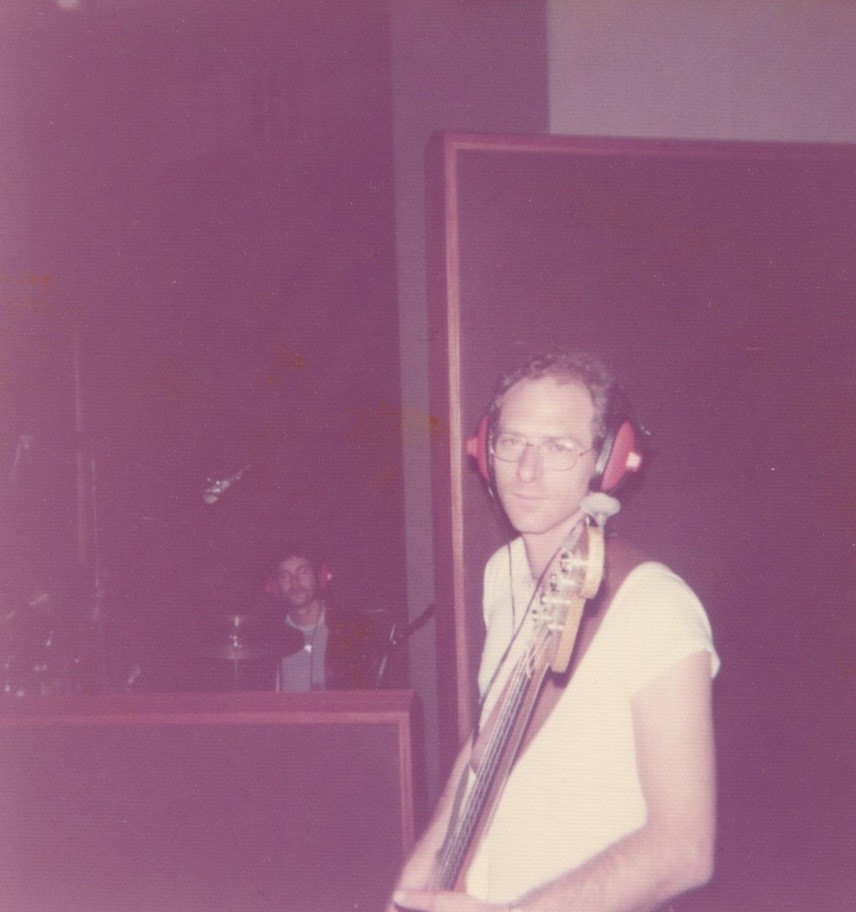

Bob Staley played organ, and sang most of the songs, at least the originals. We also did a list of covers, none of which were recorded. We did ‘Dance To The Music,’ ‘Sing A Simple Song,’ that sort of stuff, where there were horns already in the arrangements. Jeff Ervin played the sax, provided some (all?) of the horn arrangements, played the flute… oozing talent, in other words. On bass, Dave Dunaway, a high school friend of Jeff’s, and clearly one of the best two bassists with whom I was ever favored to play, the other being Phil Robyn of Asgard. Dave sings the high harmony on the chorus of ‘Flite,’ and also sang on a lot of our cover material. Bill Thomas was on drums, and drove a taxi when he wasn’t drumming. He was jazzy enough to work well with Jeff and Dave, both of whom had some jazzy roots too. Jeff was like a conductor, and a sort of hinge that connected the horn section to the rhythm section. Hanging from that hinge were Jean Hintermann on trumpet and Larry Mallarino on trombone. And then there was me, playing electric guitar. I sang on some of the cover material, but also the lead on ‘Two Hats In One,’ with a little backup help from Dave Dunaway.

Tell us about the recording under the name of ‘Flite’. Was this the same story of recording an album and not being able to release it?

Not really – we never recorded a whole album of stuff as such. This Out-Sider LP is the first time any collection of Stow Lake recordings have been anthologized this way.

The group consisted of seven members… Tell us what was the main concept behind the group?

I may not be the best person to answer that, since I was the new kid in town! Very loosely, it was a similar sound and theme to someone like Chicago or Blood, Sweat & Tears, but leaning a little further in a soul or Latin direction.

The band consisted of:

Bob Staley – organ, folk guitar, lead vocals

Bob Hardy – electric guitar, lead vocals on ‘Two Hats In One,’ piano on ‘Flite’

Jeff Ervin – sax and flute

Jean Hintermann – trumpet

Dave Dunaway – bass guitar, harmony vocal

Larry Mallarino – trombone

Bill Thomas – drums

Where are those recordings recorded? What do you recall from the studio?

I’ve no idea what became of the masters. It’s lucky that I kept mixdown copies, or all would probably be lost.

McCune Sound seemed kind of spartan to me, but of course, we were probably in “the cheap room” or whatever, with very little in the way of signal processors. My mixdowns don’t even have any reverb that I can hear. The Golden State Recorders tapes were done quickly but nicely, with Leo de gar Kulka himself running the board. At the time, the reverb he put on the horns sounded a bit too Herb Alpert style to me, but over the years I’ve come to love it. On the unedited mixdown tape, you can hear him say the track name and take the number. No big deal, except that he’s become kind of a minor god in studio production history, alongside people like Wally Heider. So it is kind of a big deal, content-free though it is. For no reason I can say, I was tasked with playing the piano on ‘Flite’. It’s fine, even though I’m not much of a keyboard player!

Out-Sider (Guerssen imprint) released several live tracks from the Fillmore West in 1971. Tell us about the live aspect of the band and with whom you all played?

I don’t remember much about who else was playing. These were, after all, audition nights, and mostly acts that were seldom or never heard from again. I think we did a last minute (i.e., with very little notice or preparation) performance in December 1970, and then came back for a more orderly audition night in January 1971, with friends in attendance and so on. Our friends must not have been loud and rowdy enough, or just too few, because Bill Graham didn’t offer us any additional bookings: the audience response was much of how he chose his acts. I just remember lugging that Hammond organ up and down the concrete stairs behind and beneath the stage! It was a serious struggle!

What about Songs (‘Vertigo’). What does that material consist of and where was it recorded?

Most of the early recorded matter was begun in mono, on a borrowed Nagra, and later recorded in living rooms and such on a big AKAI 4-track reel deck. Some of the mixing was done with TEAC 3340s too, when we were well into the 4-track recordings. Chris Quinn wrote a lot of lyrics, only a fraction of which ever found their way into these songs. Tim Timmermans was the most prolific writer of finished songs, which tend to be less hard rock than I wrote, and more in the style of Yes, or maybe the lighter Led Zeppelin tunes.

‘Vertigo’

This is a co-authorship involving J.A. “Tim” Timmermans and Craig Chaquico. (Yes, THAT Craig, later of Jefferson Starship.) Tim plays drums and acoustic guitar on this one.

‘No Time For The Blues’

Written by Arthur Juncker, who also plays piano on the recording.

‘Songs (For Chris)’

This was my first attempt at a solo in the 21/8. This one is entirely by Tim Timmermans. He also plays the drums, piano, acoustic guitar and flute on this.

‘Too Much, Too Fast’

A collaboration between myself and Christopher Quinn. I even have the copyright form and lead sheets for this one! It says (c) 1975, which is when I registered the copyright, but the recordings were actually done earlier than that by roughly a year.

‘Song For Me’

This is another one for Tim. He did the acoustic guitar, drums, flutes, and I think some of the electric guitars (I let him use my Strat, so pretty sure!) I think he sang some of the harmonies, too.

‘We Are’

Tim again. He sings the lower vocals and plays acoustic guitar.

‘On This Day’

Tim again! He was the most musically adventurous writer among us, and it shows here. He did the drums, acoustic guitar, flutes, and some of the synths. He also contributed some of the vocal harmonies. The bass guitar that was used for many of the Songs’ songs was a borrowed Gibson solid body with really old, dead flatwound strings on it. It actually belonged to Jack Traylor, who was a sometime lyricist for Jefferson Airplane/Starship and Steelwind, and had been Tim and Craig Chaquico’s English teacher in high school. There were many places where I had to pick really hard, and then compress, to get any note at all out of those old, dead strings.

Did you do any live shows playing those tunes?

Probably there weren’t any. With only three of us as full-time members, it was near impossible to play these elaborate arrangements onstage.

What followed for you?

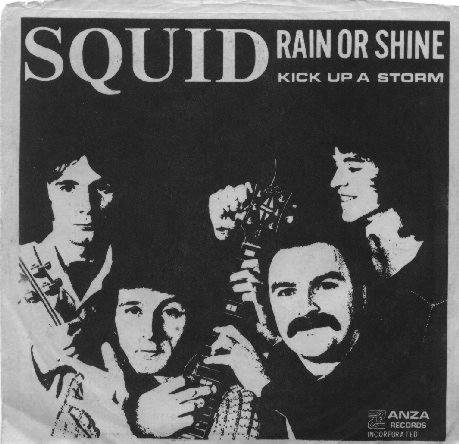

At the same time that I was doing Songs, I was also doing Squid, which was a somewhat Beatle-ish band, more pop and less experimental.

Both of those ended in 1975, and I eventually moved to L.A. to start a whole new series of bands and projects for about 9 years.

I would love to hear more about Impulse and The Power.

Both were collaborations with Chris Quinn. Impulse was a little like The Doors, a little like Jefferson Starship, a little Moody Blues, a little Led Zeppelin-ish. The Power came out of Impulse when a guitar player and a keyboard player left the lineup, and we added a new bassist. It was more openly hard rock, not punk as such but leaning toward heavy metal. The Power was basically a 3+1, like The Who or Led Zeppelin.

Is there any unreleased material you were part of still available?

I think we’ve covered most of the interesting parts, at least up until about 1976. After that, it’s not so much psychedelic as rock, country or some combination that would fall outside of your stylistic theme.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time with all the bands? Which songs are you most proud of? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

That’s a tough one! Some peak moments came later in my musical life, and a few earlier than 1970-1975. I do especially like that instrumental break in ‘So Let Go’ that we’ve talked about (Asgard), or the almost-falling-off-the-edge solo in ‘Too Much, Too Fast’ (Songs), or the flying-through-outer-space quality of ‘On This Day’ (Songs), or the concise but emotionally fraught mini-solos in the Golden State Recorders version of ‘Flite’ (Stow Lake). There were some memorable moments in the late ’70s and early ’80s, but by then it was not really psychedelic anymore, but more in the direction of Loggins and Messina, or Buffalo Springfield, or Bruce Springsteen.

What currently occupies your life?

Strangely enough, I’ve returned to my roots in some ways, and yet gone off in a completely different direction too. I’ve produced a number of recordings of surf covers, covers of other kinds of pop instrumentals, and quite a few country and rock amalgams, even some humorous songs, particularly some I did with Dick Peddicord, another veteran member of the Blue Cheer entourage, and the author of ‘Oh Pleasant Hope’. I’ve also done a series of what I call meditative sound designs, basically meditation music tracks with binaural beats embedded in them, to assist and support meditative states, and some more dedicated to sleep, nothing like rock or pop at all. Most of those are available on Bandcamp, as ‘Forth Dimension Meditation Sounds,’ and a couple more coming soon.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Thank you! I’m running out of words, so please excuse me if I leave you with thanks, and I hope you enjoy the music.

Klemen Breznikar

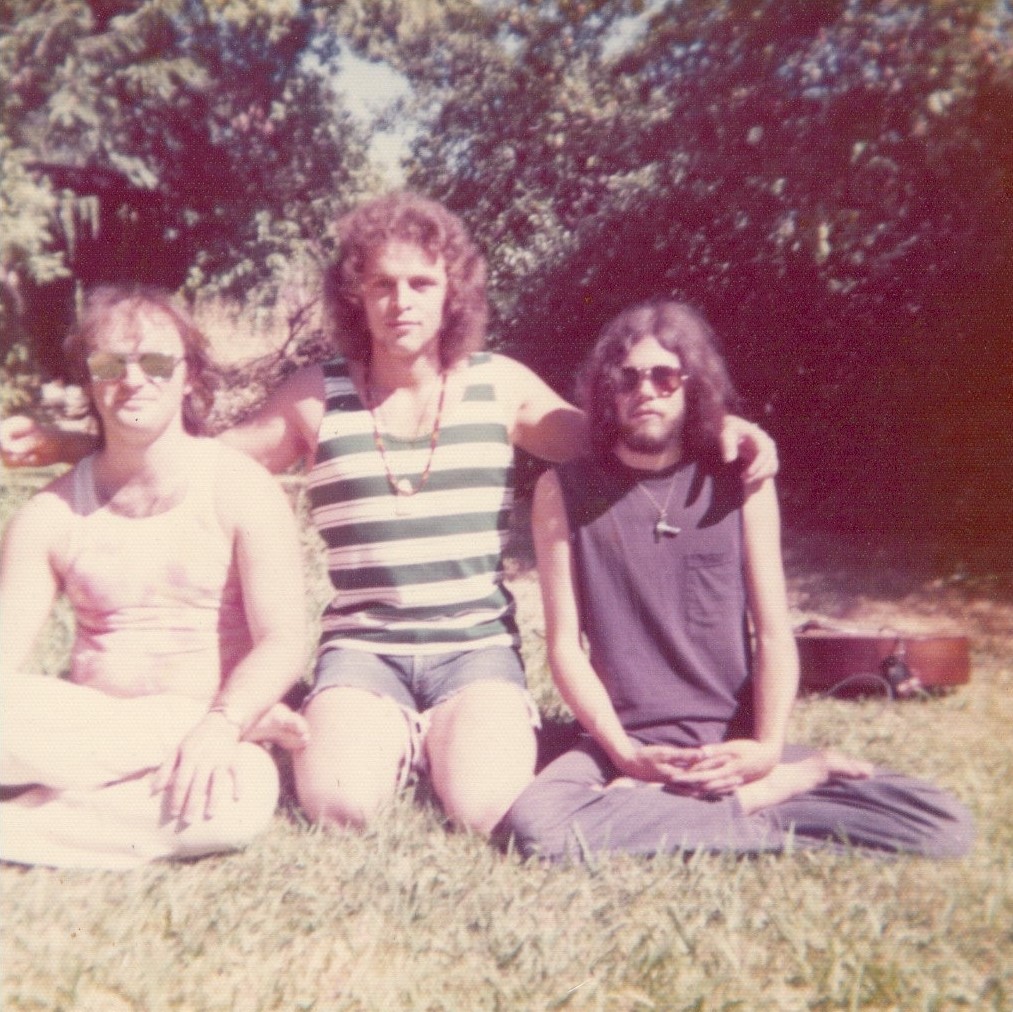

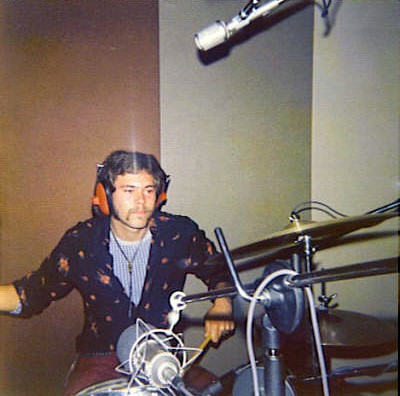

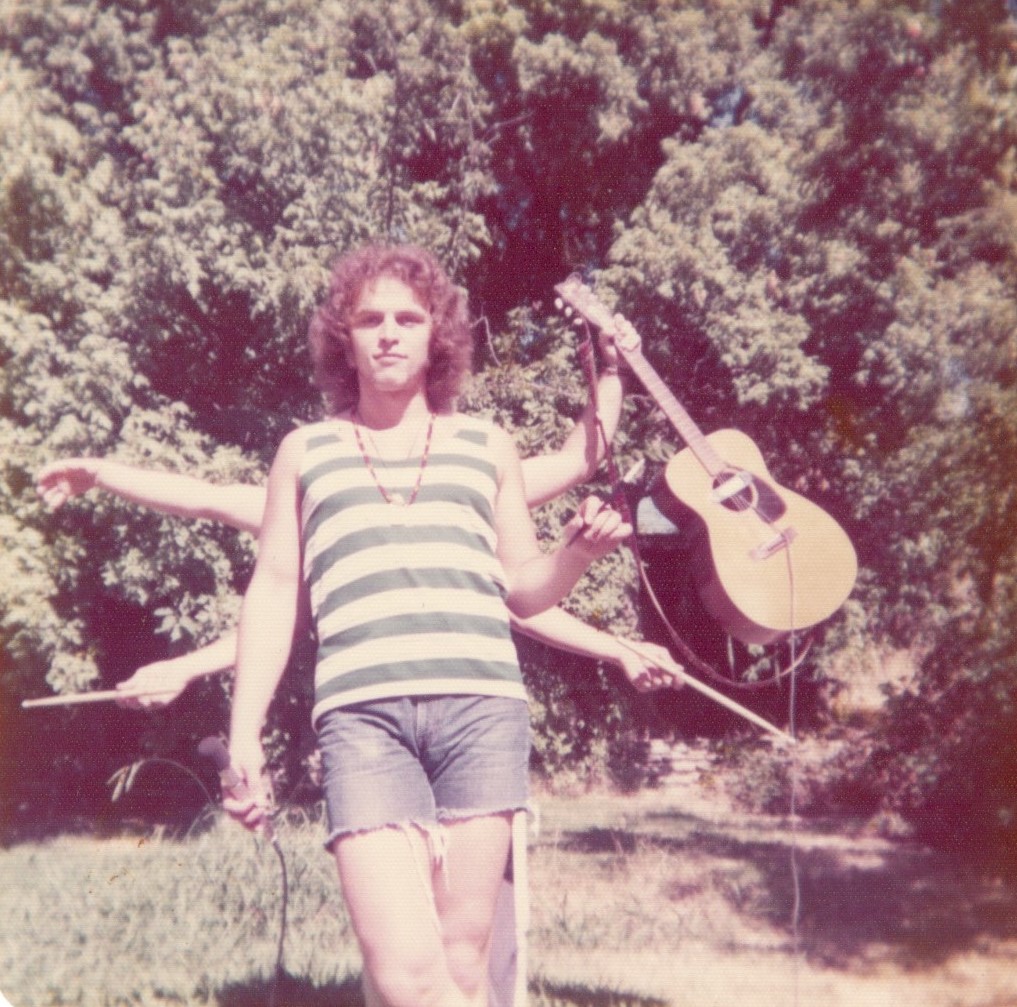

Headline photo: Songs at Fair Oaks (circa 1974) | Bob Hardy, Christopher Quinn, Tim Timmermans | Photo by Nancy Hardy

Forth Dimension Meditation Sounds Bandcamp

Guerssen Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube

Asgard | Interview | Jake “Gelon” Lau | “Lost San Francisco Album from 1972”