Bill Leader | Interview | “I made Bert Jansch’s very first recording in my flat”

Bill Leader is a legendary English recording engineer and record producer being involved in particular with the British folk music revival of the 1960s and 1970s, producing records by Davey Graham, Bert Jansch, John Renbourn and many others.

Bil Leader was originally from New Jersey born to British parents that returned to the UK while he was still a child. In 1955 he moved to London to work in a film library at the Polish Embassy, with the intention of working in the film industry. He began working for Topic Records and particularly recorded some of the Irish folk musicians who were in London in the late 1950s, as well as releasing a Ramblin’ Jack Elliott record for Topic. Leader recorded many of the artists from the scene including John Renbournand Bert Jansch. In 1969 he formed two record labels. The Leader label was inspired by Alan Lomax with extensive liner notes, while Trail Records was more focused on the folk revival scene. Leader was also in charge of the Audio Department at University College Salford. Being still active today, he is concentrating on transferring his huge collection of 78, 33 and 45 rpm records onto more modern systems.

“I try to get whatever the artist has in their head, to come out of the loudspeakers”

It’s really fantastic to have you. As far as I understand you’re keeping busy concentrating on transferring your huge collection of 78, 33 and 45 rpm records, how much is there still to do?

Bill Leader: We’ve recently been moving and consolidating my collections rather than transferring them to a different format. Prompted initially by some upcoming building work at home, to gain space, we offered to donate my large, if well-worn, slightly crackly collection of 78rpm records to the British Library’s archive. Unfortunately the offer initially landed on the wrong desk. By the time we got a positive and enthusiastic response from the library, we had run out of time and so the collection had to be dispersed quickly.

We’ve also been sorting out my own recordings on 33 and 45 and trying to fill in the gaps in my collection – when I was originally recording and issuing the records I didn’t always set aside copies for later!

Would you like to tell us about the process? What equipment do you use and what are some of the more interesting records that are pretty much unavailable for a wider public?

I’ve not been involved in record production for many years. When it came to transcribing from old formats, there was not a lot of “off the shelf” gear available back in the 50s and 60s. I just did the best I could with what I was able to get hold of. Being able to play back records at the right speed and with a stylus that sat comfortably in the record’s groove was very important, and not always as easy as you might think.

The monetary, cultural and entertainment value of a record is a shape-shifting thing. As time goes on, and reputations are reassessed, a performer’s standing gets reassessed too. Methods of retrieval are constantly improving. I tried never to destroy a good performance, even though it was on a very worn damaged 78, because future technology might be able to retrieve it. Even then it was my own, personally biased decision as to what was a good performance in the first place.

You were born in New Jersey to British parents, when did you move back to Dagenham and what was growing up there like for you?

I was two years old when my parents returned to London. My dad, who was a factory worker, got a job in the recently opened Ford’s factory in Dagenham, Essex. We got a house on the edge of the new, big London County Council (LCC) housing estate that was being built nearby. I spent five childishly happy years there.

Was there a certain moment in your life when music completely mesmerized you?

I can’t recall being mesmerised by a piece of music; intrigued, delighted, satisfied, many times, I have sometimes been moved by a musical occasion or event though.

Did you play any instruments? What are some of the early musicians you were fond of?

Don’t give me any musical instruments to play. I’ll drop them, bend them, break them. I’ll do anything but get a tune out of them.

The early musicians that I was fond of were engraved on my mum’s 78s. For instance, a fine body of fighting musos, like the band of the Coldstream Guards battled their way through a lot of tunes from Gilbert and Sullivan comic operas; and the Irish tenor, Count John McCormack sang the songs of Thomas Moore. Jack Payne was there with the BBC Dance Orchestra, and Peter Dawson, whose baritone voice proved eminently recordable, whether using the old acoustic method or the newfangled electric recording, that was the standard method in the 30s.

What brought you interested in being a recording engineer?

It all started with my mother’s collection of records, played on her HMV wind-up Gramophone.

What led you to move to London in 1955? You started working in a film library at the Polish Embassy, what exactly did you do?

When I got to be 21 years old, I finished my factory apprenticeship and got called up for 2 years National Service. Upon release, I shook the dust of Bradford (at that time it was more soot than dust) from my feet and took advantage of an opening in the film library at Films of Poland, which was housed in the Polish Cultural Institute, in London. It was at the top end of Portland Place. The Polish Embassy was further down the street, the BBC’s Broadcast House being at the bottom. A different locale from Saltaire, near Shipley, near Bradford, in the West Riding of Yorkshire.

Topic Records formed in the late 30s and were mostly covering traditional and contemporary folk music. You worked there recording some of the Irish folk artists from the late 50s. Would you like to talk about some of the most interesting recordings you did?

Topic Records was founded as part of Workers’ Music Association (WMA) a year or two before WWII. Currently it claims to be the world’s oldest independent record label. It probably could also claim to be the world’s first record club. A club is what it set up to be; and that’s what the prefix TRC on their 78 releases stands for.

In its early days it was more concerned with music with a political slant. That, occasionally, included folk music. During the fifties, they got deeply involved with recording the folksingers Ewan MacColl and Bert Lloyd for American labels.

I joined the WMA at the tail end of this period and had the opportunity to record some of the American musicians that appeared to be invading London at that time. People like John Gibbon, Guy Carawan, Ralph Rinzler, Rambling Jack Elliott and Peggy Seeger. I also got the chance to record some of the Irish musicians, who were resident in London. The startling Cork street-singer Margaret Barry and the wonderful Sligo fiddle player Michael Gorman, come to mind.

One of the highlights must be a Ramblin’ Jack Elliott record for Topic, what do you recall from it?

It was folk singer/playwright Ewan MacColl who put me onto Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, when Jack and his wife June first hit London town —all cowboy boots, Stetson hat and Gretsch guitar. We had many wonderful recording sessions with him both in our ramshackle London studio, and, memorably, on a yacht, tied up in Cowes harbour on the Isle of Wight.

You also had to work in a record shop specialised in folk/blue/jazz records in Oxford Street, London. Do you miss those old days when vinyl format was the way to go? For us younger generations it’s hard to imagine there was much more excitement from the general public when it comes to music. What do you think?

Recorded music has appeared in many formats since its introduction 150 or so years ago. As each new format has hit the market, the marketers have declared that: “Now, at last, we have the absolutely perfect, life-like production method!” “It’s as though you are actually in the room with the musicians!!” Now they are more interested in creating a sort of fantasy aural world for the performance to exist in. But a nostalgic myth has grown that there’s something special about vinyl. No format is perfect. Some have imperfections that you can learn to like, until something better comes along.

What were the circumstances of meeting Nathan Joseph who had set up Transatlantic Records?

I was working in Collets’s folk and jazz record shop in London’s New Oxford Street, and a very young man came in to sell me some records that he’d brought in from America. He told me that in addition to importing US records, he intended to record and market some in U.K. It was Nat Joseph, and when I became free-lance, as I did soon after, he became a major client. I supervised a lot of his early releases on his Transatlantic label, Billy Connolly, The Dubliners, Gerry Rafferty amongst others.

What kind of equipment did you use in the early 60s? What control speakers did you enjoy having? Tannoy?

In the early sixties I was involved in various styles of recording sessions. I was out on the road, recording performers (both traditional singers and revival groups) wherever they lived or performed: alfresco, location recording you might call it. I was also overseeing sessions in commercial recording studios: much more like conventional recording. My location work was done on my own, modest equipment, Usually a Revox tape recorder, a couple of decent microphones, and a good pair of headphones. My conventional recordings were done using the studio’s gear.

There must have been a lot of improvisation on your part due to the limited amount of budget, right?

One did what one could.

… but still those records sound incredible these days, why do you think?

Thanks for the compliment. I developed a method for location recordings. After I’d got back from wherever I’d done the recording, I’d sort out the takes that I intended to use; book time at a good value studio, and there I would copy the selected takes, trying to get the best sound I could, using the studio’s outboard, auxiliary facilities such as: equalisation; reverberation; compression; expansion et cetera, but only if I really had to.

You actually did a lot of recordings in your own flat. How did you condition the room and What kind of equipment did you use? What are some of the recordings you would like to highlight?

I did a lot of recording in my two-room flat in Camden Town. I’ve read several descriptions by performers of how it was done, few of them resemble reality. The house was Victorian; the rooms were big. Big rooms sound better than small rooms, always have; always will. I found that I had accidentally also sound-treated the room by having the walls shelved out with records and tape boxes. It worked very well. So you don’t have to believe all those stories about egg boxes and clothes cupboards.

“I made Bert Jansch’s very first recording in my flat”

How did you enjoy the music of John Renbourn and Bert Jansch, two incredible artists that you recorded in your apartment? Do you have any particular story about it?

I found Bert and John were a pleasure to work with. I made Bert’s very first recording in my flat. I had to borrow a decent microphone (I didn’t have one of my own, at the time). Bert had to borrow a guitar (he’d had a mishap with his own, the night before.). I did the recording way back in the early 60s, and it’s never been out of print since then. Later, when I came to record Bert and John, all went smoothly. I took the raw takes for sweetening to Nic Kinsey at Livingston Studios at New Barnet – my studio of choice.

Was the decision to start your own label a difficult decision or was the income that better by the end of the 60s?

I had figured out that, provided we could sell direct by mail (rather than through shops at a discount), we could break even after selling about 100 copies of a record. After all, our overheads were low—we worked from home; had few studio costs, no ambition to get rich quick, and one hundred copies was an achievable amount. One drawback that I foresaw was that if a record was bought in a shop, it could be played before being bought, and the purchaser could feel assured that they had bought the right stuff. On the other hand, if a flyer in the post was their first and only bit of information about the disc, they would not be able to judge whether it was a record that they would want. We were hoping that our mail shots would go round the world, and if some ethnomusicologist on some foreign shore picked up information about one of our records called “English Folksongs,” he might not know whether it contained performances by some rural singer, or a city based folk group. He might treasure one, but hate the other. So in what I like to think of as my wisdom, I decided to put out truly traditional performances on the Leader label, and derivative stuff on a label called Trailer. It was a bit of wordplay I suppose: both words have a use and meaning in the audio industry.

What was the concept behind Leader and Trailer Records?

The concept behind Leader and Trailer, I guess, was to make a “carry home” version of the folk revival. Not that that was the philosophy propounded at the time. In fact, I’ve just thought of it in answer to your question. That doesn’t make it any the less true, though,

What would be some of the most exciting projects on The Leader thinking back?

At this distance in time (forty years, or thereabouts) I remember each Leader and Trailer project being exciting in some way for others.

How did you get involved with the Audio Department at University College Salford?

My arrival in the groves of academe was by sheer luck. Just as my recording adventures were hitting the rocks, I heard that Salford College of Technology was seeking to start a Recording Studio Technology course. They had staff that could teach the technology, but nobody with practical studio experience. Salford was on the other side of the Pennine hills from where I was living, but reachable. I applied and got the job. The college eventually got absorbed into University of Salford, by which time I was working in Music, Media and Performance and, almost by accident, I eventually became a visiting prof.

How would you describe the London folk club scene?

I’ve been away from the London clubs for decades. I don’t know what’s going on these days. But during its early flowering, in the middle to late fifties, and its blossoming in the sixties, it was a colourful, vibrant scene.

Would it be possible for you to choose a few projects that still warm your heart?

I have a fond spot in my heart for all my recordings, and the artists who made them. .

Would you like to comment on your recording technique? Give us some insights on developing your recording technique?

I try to get whatever the artist has in their head, to come out of the loudspeakers. I also try to anticipate any problems, personal, artistic or musical that might arise and, above all, make the resulting recorded sound be believable.

What makes a good production?

I think that a good production is one that you can enjoy listening to. It’s also one that has an inherent logic to it. I know that’s vague, perhaps even incoherent. But each new production is a new venture, a new attempt by a performer to say something. Perhaps even to say something new. Treat it with consideration.

Thank you. Last word is yours.

I can’t conclude without mentioning a few of the people who helped me back then. Primarily Helen Leader (a great organiser}; Janet Kerr (a great artist and sleeve designer}; and John Gill (a great soundman).

Klemen Breznikar

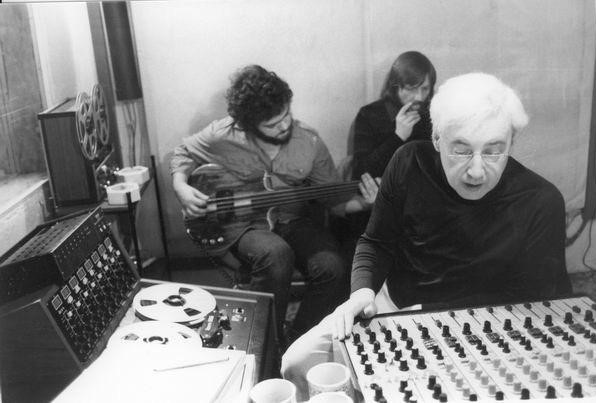

Headline photo: Bill Leader